Abstract

Background Medication reconciliation at admission to hospital reduces the prevalence of medication errors. Strategies are needed to ensure timely and efficient delivery of this service. Objective To investigate the effect of aligning clinical pharmacy services with consultant teams, by pharmacists attending post-admission ward rounds, in comparison to a ward-based service, on prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancies 48 h into admission. Setting A 243-bed public university teaching hospital in Ireland. Method A prospective, uncontrolled before-after observational study. A gold standard preadmission medication list was completed for each patient and compared with the patient’s admission medication prescription and discrepancies were noted. Unresolved discrepancies were examined at 48 h after admission to determine if they were intentional or unintentional. Main outcome measured Number of patients with one or more unintentional, unresolved discrepancy 48 h into admission. Results Data were collected for 140 patients, of whom 73.5% were over 65 years of age. There were no differences between before (ward-aligned) and after (team-aligned) groups regarding age, number of medications or comorbidities. There was a statistically significant reduction in the prevalence of unintentional, unresolved discrepancy(s) per patient (67.3 vs. 27.3%, p < 0.001) and per medication (13.7 vs. 4.1%, p < 0.001) between the groups, favouring the team-based service. The effect remained statistically significant having adjusted for patient age, number of medications and comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio 4.9, 95% confidence interval 2.3–10.6). Conclusion A consultant team-based clinical pharmacy service contributed positively to medication reconciliation at admission, reducing the prevalence of unintentional, unresolved discrepancy(s) present 48 h after admission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact of findings on pharmacy and clinical practice

-

Aligning clinical pharmacy services to consultant teams, versus wards, can significantly impact the rate of resolution of unintentional medication discrepancies at hospital admission.

-

Post-admission ward rounds are a meaningful point in the inpatient episode for constructive clinical pharmacist contribution and multidisciplinary collaboration.

-

Evaluating and implementing service changes based on ongoing research cycles supports in an iterative process of continuous quality improvement.

Introduction

Medication errors at admission to hospital are common and may persist during and after the episode of care [1–3]. The majority of clinical pharmacist interventions at the hospital admission interface relate to unintentional omission of medication [1, 3, 4]. There is evidence to support the benefit of medication reconciliation as an intervention to reduce the prevalence of medication error, potential adverse events and adverse events [5, 6]. Effective medication reconciliation requires not just an accurate list of the patient’s actual pre-admission medication use but also identification and resolution of any discrepancies present on the hospital prescription chart; and documentation of the rationale for intentional changes [7]. Absent, incomplete or asynchronous communication can be an obstacle to effective medication reconciliation [2, 8]. Written communication in the form of documentation in patients’ healthcare records is important. However written notes are an asynchronous form of communication and, used alone, do not always result in timely resolution of medication discrepancies and may contribute to further ambiguity [2, 8–10]. Bidirectional, synchronous communication and face-to-face contact has been identified as an important aspect of successful multidisciplinary teams and in establishing collaborative working relationships [11, 12]. Research in the primary care setting has shown that trust, interdependence, and the quality of communication (i.e. openness and bi-directionality) are determinants of successful doctor–pharmacist collaboration [13]. There is evidence that collaborative pharmaceutical care, involving physicians and pharmacists, improves medication reconciliation and reduces the prevalence of medication error [14–16].

Pharmacist attendance at post-admission ward rounds offers one potential way to increase such interaction [17, 18]. Such attendance has been suggested as an effective means of utilising the pharmacist’s competence at the point of prescribing and decision making, rather than the retroactive approach which results from retrospective prescription review. It also enables greater acceptance of pharmacist recommendations regarding medicines optimisation [17]. Having an accurate picture of pre-admission medication use permits safe and informed prescribing decisions during the patient’s admission. However, there is relatively little evidence available regarding the benefit of pharmacist participation on ward rounds [18].

A new team-based model for clinical pharmacy was introduced at the study hospital in 2010. Prior to this, clinical pharmacy services were structured such that each pharmacist was responsible for patients on one or more ward. This required the pharmacist to communicate with multiple doctors on different teams on a daily basis. When a patient was transferred from one ward to another, that patient’s pharmaceutical care was transferred from one pharmacist to another. Previous research at the study hospital examined the effectiveness of medication reconciliation at admission under this model and identified that discrepancies were more likely to be resolved if verbally communicated to the prescriber, rather than in writing [8]. Further, many identified discrepancies remained unresolved despite written communication in the patient’s healthcare record. The new team-based model aimed for the pharmacist to develop a collaborative working relationship with the consultant team providing care to each patient. This model was commenced on a trial basis in 2010. Having changed the model of clinical pharmacy services delivery, we wanted to determine what improvement, if any, had been made to admission medication reconciliation outcomes as a result.

Aim of the study

To evaluate the effect of a team-based clinical pharmacy service, versus a ward-based service, on the prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancy, per patient and per medication, at 48 h after admission.

Ethics approval

Approval to carry out the study was granted by the Ethics Committee at Naas General Hospital.

Method

This study was a prospective, before-after uncontrolled observational study examining the effect of a consultant team-based clinical pharmacy service where pharmacists attend post-admission ward rounds, versus a ward-based service, on the prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancy at 48 h after admission.

The “before” phase of data collection occurred in 2009 when clinical pharmacist services were ward-based, and the “after” phase of data collection occurred in 2011, 6 months after the changeover to team-based service was introduced. Both studies were conducted in Naas General Hospital, a 243-bed acute hospital with a 24 h accident and emergency service, serving a population of over 180,000.

In our hospital, consultants operate post-admission ward rounds starting in different wards or at different times depending on individual work patterns. All patients admitted under the consultant’s care, over the previous 24-h period from 8 a.m. to 8 a.m., are reviewed. A typical post-admission ward rounds starts in the emergency department (ED) at 9 a.m. and is attended by the consultant and between 1 and 4 junior doctors. A typical format of the ward round involves a junior doctor presenting the case to the consultant who then examines the patient and decides on the treatment plan.

Description of the team-based model

A pharmacist is assigned to each consultant team and attends the post-admission ward rounds with that team if it falls on Tuesday to Friday. (As the pharmacy department is closed at weekends and three teams will have been on-call in the intervening period (Friday, Saturday and Sunday), attending ward rounds on Mondays is deemed impractical at the current pharmacy staffing level.) At the same time, other pharmacists obtain and document gold standard pre-admission medication lists (GS-PAMLs) for the newly admitted patients. These pharmacists aim to have any medication reconciliation discrepancies or other pharmaceutical issues identified and documented before the consultant team reach the patient, although this is not always possible. Other pharmaceutical issues are typically identified as part of a parallel medication review performed by the pharmacist, examples of issues may include non-compliance, a potential adverse drug reaction noted, an untreated indication, unnecessary polypharmacy, patient having difficulty using medication at home. The pharmacist’s note was documented in the clinical notes in the healthcare record, which was available before or during the ward round, although the logistics of post-take care make it likely that these notes are reviewed at the point of patient review on the ward round, rather than before. Figure 1 describes how pharmacist duties might be organised on a typical day within the old and new models.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adults over the age of 18 years admitted via the ED were eligible for inclusion if they reported the use of at least three medications prior to admission. Patients were excluded if they were unable to speak English and an interpreter was not available. Using a random number generator in Microsoft Excel, patients were randomly selected from a list of newly admitted patients generated daily through the Patient Information Management System.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on the primary outcome, unintentional, unresolved discrepancy(s) at 48 h post-admission, the prevalence of which was previously identified in the study hospital as 67% of patients. To demonstrate a reduction from 67 to 45%, 90% power, 5% significance level (two-sided) required 51 per group, total 102 patients.

Data collection

A GS-PAML was built for each randomly selected patient. This was a ‘best possible’ list of medication the patient was actually using prior to admission, including the name, dose, frequency and route of administration of each medication. This was constructed using at least two sources, including patient or carer interview, patient’s own drugs or own list of drugs, community pharmacist and general practitioner records. Where patient non-compliance (omission) with prescribed medication was identified, this was recorded as a pharmaceutical care issue, but was not included in the GS-PAML, which was intended as a reflection of the medication the patient used. The GS-PAML was compared to the admission medication prescription (AMP), and any discrepancies were documented in the patient’s healthcare record. At this stage, discrepancies were considered to be resolved if there was documentation regarding the changes in the patient’s healthcare record or if the data collector, a clinical pharmacist, considered there to be a rational reason for changes based on the patient’s presentation (e.g. withholding anti-hypertensives in a patient with hypotension). In some cases it was possible for the discrepancies to be resolved using endorsement by the clinical pharmacist (e.g. specifying whether an immediate-release or extended-release formulation of a medication was to be used).

Forty-eight hours after admission, the identified discrepancies were reviewed. This time period was chosen to allow time for the course of care, including medication reconciliation, identification of medication discrepancies, review and resolution of discrepancies, to occur. The discrepancies were considered resolved if the AMP had been amended to reflect the GS-PAML or the team had explained the discrepancy as intentional in the healthcare record. In the ‘before’ group, discrepancies were confirmed verbally by the physician at that time as being not intentional [8]. In the ‘after’ group, the pharmacist who attended the ward round was contacted to determine if they could confirm whether any outstanding discrepancies were intentional. Any outstanding unresolved discrepancies were categorised as intentional or unintentional by contacting the consultant team responsible for the patient.

Clinical significance testing

Two random samples of patients included in the study were selected; the first comprised 12 patients with an unintentional unresolved discrepancy and the second included 10 patients where all initial discrepancies were completely resolved at 48 h post admission. The potential for patient harm, had the discrepancies not been resolved, was assessed using a reliable and validated tool, which employs a visual analogue scale (0–10: 0 represents no harm; 10 represents death) [19]. Six assessors individually assessed and scored the cases in the ‘before’ study, and four assessors assessed and scored the cases in the ‘after’ study. Assessors included medical consultants, hospital clinical pharmacists, general practitioners and community pharmacists. A mean score was then calculated, and categorised as having the potential to cause minor (<3), moderate [3–7] or severe harm (>7).

Data analysis

The statistical analysis software package, SPSS Statistics, version 22, was used to support analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to represent process and patient outcome measures. Associations between categorical variables were examined using the Chi square test. An a priori level of significance of 0.05 was set. Distribution of data was examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test. Continuous parametric data were described as mean (standard deviation, SD), and differences between groups examined using the Student t test. Continuous non-parametric data were described as median, (inter-quartile range IQR), and differences between groups were examined using the Mann–Whitney U test. Logistic regression was used to model the association between a patient experiencing an unintentional unresolved discrepancy, and the study group, adjusting for potential confounders (age, number of medication per patient, number of comorbidities per patient). Odds ratio (OR), with 95% confidence intervals (CI), were calculated.

Results

A total of 52 patients were included in the before group and 88 patients in the after group. The population characteristics were compared and no statistically significant differences were found between the groups (see Table 1).

In the before group, 35 patients (67.3%) were affected by an unintentional unresolved discrepancy at 48 h, compared to 24 patients (27.3%) in the ‘after’ group. This represents a statistically significant decrease (χ 2 = 21.5, df = 1, p < 0.001).

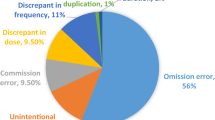

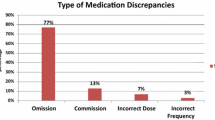

The unintentional unresolved discrepancy(s) at 48 h represented 13.7% (n = 96) of all medications in the before group and 4.0% (n = 43) of all medications in the after study (χ 2 = 54.8, df = 1, p < 0.001). The frequency of each type of unintentional unresolved discrepancy is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Logistic regression identified an association between a patient experiencing an unintentional unresolved discrepancy and study group, having adjusted for patient’s age, number of medication and number of comorbidities. Patients in the “before” group were almost fivefold more likely to experience one or more unintentional unresolved discrepancy (adjusted OR 4.9, 95% CI 2.3–10.6). The only other variable associated with presence of unintentional unresolved discrepancy was number of medications, identifying that for every extra medication a patient was using, there was 10% greater likelihood of experiencing an unintentional unresolved discrepancy (adjusted OR 1.11, 95% CI >1.01–1.22).

In the after group, the GS-PAML was completed and documented in the patient’s healthcare record before the patient was seen on the post-admission ward rounds for 71.6% (n = 63) of patients. Allowing for the fact that pharmacists were not present on all post-admission ward rounds, as described above, a pharmacist was present on the round for 92.3% (n = 48) of the patients where they would have been expected to attend the round. There was no pharmacist present on the ward round for the remaining patients due to acute staff shortages. A pharmacist was present on the ward round for 48 (54.5%) of the after group.

Clinical significance assessment

The majority of the unintentional unresolved discrepancies (n = 34: n = 22 before; n = 12 after) were judged to have the potential to cause minor harm (54.5% of unintentional unresolved discrepancy (n = 12 of 22) in the before group, 58% (n = 7 of 12) in the after group). The remaining unintentional unresolved discrepancies were judged to have the potential to result in moderate harm [45.5% (n = 10 of 22) before, 42% (n = 5 of 12) after]. The clinical significance of the resolved discrepancies (n = 30: n = 20 before; n = 10 after) was judged to risk the patient experiencing moderate harm [70% before (n = 16 of 20), 50% after (n = 5 of 10)] and minor harm [30% before (n = 6 of 20), 50% after (n = 5 of 10)] had these discrepancies not been resolved. None of the patients assessed were judged to have a resolved or unresolved discrepancy with the potential to cause severe harm.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that a team-based clinical pharmacy service, with pharmacists attending the post-admission ward round, versus a ward-based admission service, led to significant reduction in the prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancy present 48 h after admission. The majority of discrepancies were identified as carrying the potential to cause minor or moderate patient harm if left unresolved. Clinical significance of resolved discrepancies was assessed as being higher than for unresolved discrepancies, demonstrating the benefit for patients as outlined in the ‘before’ study was maintained in the new model.

The finding that pharmacist attendance at ward rounds can contribute positively to medication safety is consistent with previous work exploring pharmacist ward round attendance in an English hospital [17]. The 40% absolute reduction in the proportion of patients experiencing one or more unintentional unresolved discrepancy is similar to the 30% reduction identified by van den Bemt and colleagues in their multi-centre study investigating the impact of pharmacy-based medication reconciliation [20]. Internationally, observational studies of acutely hospitalised patients consistently identify a high proportion (>30%) of patients experiencing unintentional discrepancy at admission [1, 3, 20–23], with omission being the most common discrepancy type [1, 3, 20–23], and with a minority of discrepancies carrying the potential to cause serious harm [1, 3, 23]. The findings of this study are consistent with that.

The findings support sustaining the implemented team-based model of pharmacist involvement at admission, consistent with previous findings regarding pharmacists working collaboratively with physicians [15, 16]. In comparison to the previous traditional ward-based admission service, the pharmacist made more interventions per day, which carried a greater perceived clinical significance. The findings also complement another Irish study demonstrating that collaborative pharmaceutical care between clinical pharmacists and consultant teams reduces the prevalence of medication error and improves prescribing quality [14, 24].

There are a number of potential limitations to our study. Data were collected during discrete phases and at one site, thereby limiting the generalisability of findings beyond the study population. It is possible that a clustering effect was present at the level of the consultant-team. Although we did not adjust for this in our analysis, descriptive analysis identify that there was no difference in the prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancy across the consultant-teams. Hospitals with different specialities, work practices and staffing levels may face different challenges in implementing a similar service [7]. Our before-after study design meant that we did not have a parallel control group, and it is possible that other changes occurring between the before and after periods may have resulted in over-estimation of the identified improvement [25]. We attempted to minimise this bias by using logistic regression, with adjustment for the patient’s age, number of medications and number of co-morbidities.

Further research is needed to determine whether a team-based model of clinical pharmacy services generates similar patient benefits in other hospital settings in Ireland. Irish policy-makers who recommend medication reconciliation for all patients at all transfer of care points should consider engaging with hospital pharmacists to identify how best to deliver medication reconciliation services in novel and innovative models of care. Great opportunity exists in the current health service in Ireland to further develop the role of the pharmacy team for the benefit of patients.

Conclusion

A new clinical pharmacy service was implemented at NGH, where team-based pharmacists conducted medication reconciliation as early as possible after admission and attended post-admission ward rounds with doctors. Relative to the traditional ward-based service, this resulted in improvements in medication reconciliation at admission, by reducing the prevalence of unintentional unresolved discrepancies.

References

Belda-Rustarazo S, Cantero-Hinojosa J, Salmeron-García A, González-García L, Cabeza-Barrera J, Galvez J. Medication reconciliation at admission and discharge: an analysis of prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:1268–74.

O’Riordan C, Delaney T, Grimes T. Exploring discharge prescribing errors and their propagation post-discharge: an observational study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:1172–81.

Rodríguez Vargas B, Delgado Silveira E, Iglesias Peinado I, Bermejo Vicedo T. Prevalence and risk factors for medication reconciliation errors during hospital admission in elderly patients. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38:1164–71.

Gallagher J, Byrne S, Woods N, Lynch D, McCarthy S. Cost-outcome description of clinical pharmacist interventions in a university teaching hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:1.

Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien J-aE. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(2):e010003. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010003.

Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Int Med. 2012;172:1057–69.

Fernandes O, Shojania KG. Medication reconciliation in the hospital: what, why, where, when, who and how. Healthc Q. 2012;15:42–9.

Galvin M, Jago-Byrne MC, Fitzsimons M, Grimes T. Clinical pharmacist’s contribution to medication reconciliation on admission to hospital in Ireland. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35:14–21.

Kripalani S. Clinical summaries for hospitalised patients: time for higher standards. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-005826.

Sarzynski E, Hashmi H, Subramanian J, Fitzpatrick L, Polverento M, Simmons M, et al. Opportunities to improve clinical summaries for patients at hospital discharge. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-005201.

Doucette WR, Nevins J, McDonough RP. Factors affecting collaborative care between pharmacists and physicians. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2005;1:565–78.

Snyder ME, Zillich AJ, Primack BA, Rice KR, McGivney MAS, Pringle JL, et al. Exploring successful community pharmacist–physician collaborative working relationships using mixed methods. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2010;6:307–23.

Bardet J-D, Vo T-H, Bedouch P, Allenet B. Physicians and community pharmacists collaboration in primary care: a review of specific models. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2015;11:602–22.

Grimes TC, Deasy E, Allen A, O’Byrne J, Delaney T, Barragry J, et al. Collaborative pharmaceutical care in an Irish hospital: uncontrolled before-after study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:574–83.

Khalil V, deClifford JM, Lam S, Subramaniam A. Implementation and evaluation of a collaborative clinical pharmacist’s medications reconciliation and charting service for admitted medical inpatients in a metropolitan hospital. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2016;41:662–6.

Tong EY, Roman CP, Newnham H, Galbraith K, Dooley MJ. Partnered medication review and charting between the pharmacist and medical officer in the Emergency Short Stay and General Medicine Unit. Australas Emerg Nurs J. 2015;18:149–55.

Miller G, Franklin BD, Jacklin A. Including pharmacists on consultant-led ward rounds: a prospective non-randomised controlled trial. Clin Med. 2011;11:312–6.

Walton V, Hogden A, Johnson J, Greenfield D. Ward rounds, participants, roles and perceptions: literature review. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2016;29:364–79.

Dean BS, Barber ND. A validated, reliable method of scoring the severity of medication errors. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999;56:57–62.

van den Bemt PM, van der Schrieck-de Loos EM, van der Linden C, Theeuwes AM, Pol AG. Effect of medication reconciliation on unintentional medication discrepancies in acute hospital admissions of elderly adults: a multicenter study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1262–8.

Buckley MS, Harinstein LM, Clark KB, Smithburger PL, Eckhardt DJ, Alexander E, et al. Impact of a clinical pharmacy admission medication reconciliation program on medication errors in “high-risk” patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:1599–610.

Quélennec B, Beretz L, Paya D, Blicklé JF, Gourieux B, Andrès E, et al. Potential clinical impact of medication discrepancies at hospital admission. Eur J Int Med. 2013;24:530–5.

Zoni AC, Duran Garcia ME, Jimenez Munoz AB, Salomon Perez R, Martin P, Herranz Alonso A. The impact of medication reconciliation program at admission in an internal medicine department. Eur J Int Med. 2012;23:696–700.

Tallon M, Barragry J, Allen A, Breslin N, Deasy E, Moloney E, et al. Impact of the collaborative pharmaceutical care at Tallaght Hospital (PACT) model on medication appropriateness of older patients. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2015. doi:10.1136/ejhpharm-2014-000511.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Campbell M, Ramsay C. Research designs for studies evaluating the effectiveness of change and improvement strategies. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:47–52.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the input of the doctors and pharmacists who supported the clinical significance grading of discrepancies.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byrne, S.M., Grimes, T.C., Jago-Byrne, MC. et al. Impact of team-versus ward-aligned clinical pharmacy on unintentional medication discrepancies at admission. Int J Clin Pharm 39, 148–155 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0412-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0412-4