Abstract

Grammatical dependencies, including anaphoric binding relations, are generally assumed not to ignore local relations and refer only to nonlocal relations. Ya̧g Dii (Niger-Congo/Adamawa-Ubangi, Cameroon) provides counter-evidence to this otherwise well established generalisation. Ya̧g Dii has a complicated pronominal system, originally described by Bohnhoff (1986, 2010), with pronominal forms whose distribution is determined by the nature of their antecedent, their grammatical function, and the type of clause in which they may appear. One set of forms exhibits an otherwise unattested form of nonlocality: the pronominal form and its antecedent must be separated by at least one clause, and the presence or absence of coreferent phrases in the intervening clause does not affect its appearance or distribution. The relation between this exclusively long-distance pronominal form and its antecedent seems to violate otherwise well-established locality conditions for anaphoric relations and, indeed, for grammatical dependencies more generally. We provide an analysis of binding in Ya̧g Dii which captures the binding requirements for the exclusively long-distance form in a locally constrained manner by reference to an independently motivated feature demarcating the domain in which the exclusively long-distance pronominal must appear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Locality in grammar

It is generally assumed that languages do not have grammatical dependencies that are exclusively nonlocal—there are no grammatical dependencies that operate at a minimum distance of two clauses away, for example (Fitzpatrick 2002; Sag 2010, among many others). In the context of anaphoric binding patterns, this assumption amounts to the claim that pronouns never ignore their local context. This is the subset principle of Manzini and Wexler (1987) for anaphoric binding domains, which states that larger binding domains always properly contain smaller ones, and the Locality Condition of Dalrymple (1993), stated as: “binding constraints … always refer to local elements, never exclusively to nonlocal ones”. Reference to local elements in binding may take one of several forms: an anaphor may require, allow, or disallow a binder in the local context. In all of these cases, the local context is relevant for binding conditions, in that the antecedent of an anaphor must, may, or may not appear locally.

Binding patterns in Ya̧g DiiFootnote 1 (Bohnhoff 1986, 2010) seem to run counter to these standardly accepted generalisations. The Ya̧g Dii pronominal system contains four types of pronouns with different distributions depending on the binding requirements they must obey and the type of clause in which they must appear. The set of pronouns that Bohnhoff refers to as ìi appear as subjects of certain subordinate clauses; ìi pronouns cannot be used deictically, and a discourse antecedent is not acceptable. However, the antecedent of ìi must be the subject of a clause that is at least two clauses distant. Abstracting away from linear order, the general configuration is as in (1):

-

(1)

S1[antecedent of ìi … S2[ … S3[ ìi …] …]]

S3, the clause whose subject is an ìi pronoun, may be a complement clause, an adjunct clause, a relative clause, or more deeply embedded within S2. The clause labelled S2 is a grammaticised logophoric domain, which may be either a typical logophoric domain such as the complement of a verb such as ‘say’, or a subordinate clause which does not typically constitute a logophoric domain, such as a subordinate purpose clause or a causal adjunct (Bohnhoff 1986, 2010). The ìi pronoun must be bound by the subject of S1.

The ìi pronouns are interesting from the point of view of locality conditions because the subject of S2 may be, but need not be, coreferential with ìi. It is not the presence or absence of a suitable binder in S2 that is required by ìi, but the presence of a suitable binder as the subject of S1. In other words, the ìi pronoun ignores the S2 context, and is sensitive only to the presence of a potential binder in S1. This sets the Ya̧g Dii ìi pronouns apart from more familiar long-distance anaphors whose distribution is affected by the presence or absence of a potential binder in S2.

In example (2) the ìi pronoun appears as the subject of a relative clause S3 (in which he. ìi will eat the Easter meal) which is contained within the complement clause S2 (where is the house S3 [in which he. ìi i will eat the Easter meal with his i disciples?]). The antecedent of ìi is ‘teacher i ’, the subject of the main clause S1, and a discourse antecedent j is not acceptable:Footnote 2

-

(2)

An abbreviated functional structure (Bresnan 2001; Dalrymple 2001) shows the grammatical structure of example (2) and the relation of the ìi pronoun to its antecedent, ‘teacher’, with the matrix clause labelled S1, the grammaticised logophoric domain S2, and the clause S3 whose subject is the ìi pronoun:

-

(3)

The clause containing the ìi pronoun may also appear more deeply embedded within S2, as in example (4), where ìi is separated from its antecedent by two clause boundaries. In example (4), ìi is the subject of the relative clause S3, that he. ìi created and hid. This relative clause modifies the object things of the subordinate purpose clause (so that) they know the things S3 [that he. ìi created and hid]. This subordinate clause modifies the S2 clause that I should teach everyone (so that) [they know the things S3 [that he. ìi created and hid]], which is the complement of the matrix verb say, whose subject ‘God’ is the antecedent of the ìi pronoun.

-

(4)

The structure of example (4) and the relation of ìi to its antecedent is shown in (5):

-

(5)

Example (6) is similar to example (2), but is unacceptable for two reasons: ìi does not appear in a logophoric domain, and the only potential binder of the ìi pronoun is in the next clause up and so not sufficiently distant:

-

(6)

The complement of the verb  ‘want’ is a logophoric domain, and so in example (7), the logophoric domain condition is fulfilled. In (7a), as in (6), the subject of the main clause is unsuitable as an antecedent for ìi because it is too close. Since ìi cannot take a discourse antecedent, and there is no potential binder that is sufficiently distant, (7a) is ungrammatical. The grammatical version in (7b) contains a different type of pronoun, a bi pronoun, which does not require a nonlocal antecedent.

‘want’ is a logophoric domain, and so in example (7), the logophoric domain condition is fulfilled. In (7a), as in (6), the subject of the main clause is unsuitable as an antecedent for ìi because it is too close. Since ìi cannot take a discourse antecedent, and there is no potential binder that is sufficiently distant, (7a) is ungrammatical. The grammatical version in (7b) contains a different type of pronoun, a bi pronoun, which does not require a nonlocal antecedent.

-

(7)

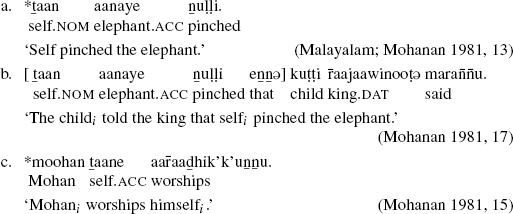

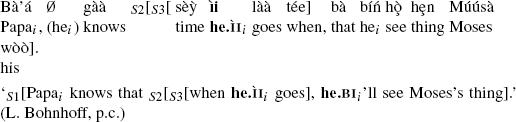

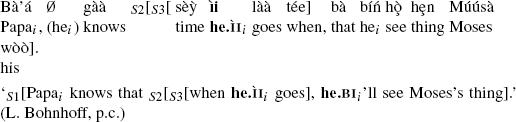

In example (8) the ìi pronoun appears as the subject of an adjunct clause S3 (he. ìi doesn’t leave) which is contained within a complement clause S2 (even if he. ìi i doesn’t leave, I’ll see Moses’s thing). The antecedent of ìi is ‘Papa’, the subject of the main clause S1:

-

(8)

The abbreviated functional structure in (9) shows the grammatical structure of example (8) and the relation of the ìi pronoun to its antecedent, ‘Papa’:

-

(9)

In example (8), there is no potential binder of ìi in S2. In contrast, the subject of S2 is coreferential with the ìi pronoun in the structurally similar and equally acceptable example in (10). The syntactic structure for example (10) is shown in (11).

-

(10)

-

(11)

Besides example (8), examples where the subject of S2 does not corefer with the ìi pronoun appear in (2), (4), (12), (13), (14), (16), and (49d). The presence or absence of a coreferential element in S2 does not have an effect on the distribution of ìi: rather, ìi ignores the S2 context in fulfilling its binding conditions.

-

(12)

-

(13)

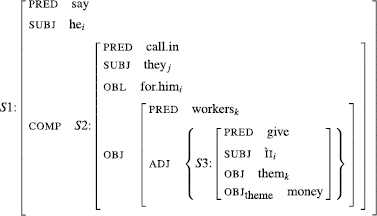

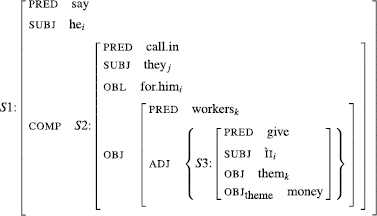

In examples (8) and (10), the binder of the ìi pronoun is the subject that immediately precedes it, but in other examples this is not the case. In example (14), the ìi pronoun appears as the subject of a relative clauseFootnote 3 S3 (that he. ìi i gave (them) money) within the complement clause S2 (that they should call in the workers S3 [that he. ìi i gave (them) money]). Although the immediately preceding subject is the pronominal subject they of S2, the ìi pronominal subject of S3 must be bound by the subject of the main clause S1, the unexpressed subject of says. The grammatical structure of example (14) is shown in (15).

-

(14)

-

(15)

A pronoun coreferential with the ìi pronoun appears in S2 in example (14), but not in the similarly-structured example (2). As shown in (3), ìi is the subject of the relative clause S3 (in which he. ìi will eat the Easter meal with his disciples), which is embedded in the complement clause S2 (where is the house S3 [in which he. ìi will eat the Easter meal with his disciples).

In examples (2), (4), (8), (10), and (14), S3 is an adjunct clause: a concessive clause in examples (8) and (10), and a relative clause in examples (2), (4), (12), and (14). S3 may also be a complement clause within S2, as in (13) and (16):

-

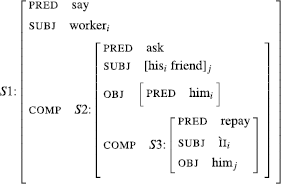

(16)

-

(17)

Thus, the ìi pronominal forms exemplify an exclusively nonlocal dependency: they must be bound by a subject at least two clauses distant. Their distribution is not affected by the presence or absence of potential binders in S2, by the relative linear order of the subjects of S1, S2, and S3, or by the argument/adjunct status of either S2 or S3.

1.1 ìi is not a standard long-distance anaphor

It is not possible to capture the exclusively long-distance nature of the binding constraints on ìi pronouns by means of standard binding-theoretic constraints. ìi does not behave like a standard pronominal, in that it does not obey only a negative binding condition such as Binding Condition B (a pronominal must be free in its governing category: Chomsky 1981). ìi pronouns require an antecedent in the same sentence, unlike pronominals, and cannot appear without an antecedent. Of course, ìi also does not behave like a standard short-distance anaphor in obeying Binding Condition A (an anaphor must be bound in its governing category), since it is not locally bound.

It is well known that some reflexive pronouns can take nonlocal antecedents; an example is Chinese ziji, which can be bound by any commanding subject, whether local or nonlocal.Footnote 4

-

(18)

ìi pronouns resemble long-distance anaphors such as Chinese ziji in requiring a binder in the same sentence and allowing binding by a nonlocal antecedent. However, ìi pronouns differ from ziji in disregarding potential local antecedents, and requiring binding by a nonlocal antecedent.

1.2 ìi does not exemplify switch reference

Binding patterns for ìi pronominal forms may appear similar to familiar patterns of switch reference, where clauses are marked to indicate coreference between arguments, often subjects, of two different clauses. Haiman and Munro (1983) provide example (19) from Pima (Uto-Aztecan), citing Langdon and Munro (1979) and personal communication from Etheleen Rosero. The morpheme glossed SS enforces coreference between the subject of cry and the subject of hit, while the DS morpheme indicates that the subjects of the two verbs are not coreferent:

-

(19)

The Ya̧g Dii ìi pronoun differs from switch reference in Pima, however, in that the ìi pronoun does not place any constraints on the reference of the subject of the immediately higher clause. In contrast, switch-reference always operates locally: according to Haiman and Munro (1983, xiii), “there seem to be no languages… in which switch-reference is marked exclusively between non-adjacent clauses. Thus, if a language has switch-reference marking between non-adjacent clauses, it will also mark switch-reference between adjacent clauses.”

1.3 ìi is not obviative

In some constructions in Spanish and other Romance languages, the pronominal subject of a subjunctive complement clause cannot corefer with the matrix subject (Quer 2006); in the Romance literature, this is generally called “obviation”.

-

(20)

Analyses of Romance obviation constructions generally assume that the binding domain for the subordinate subject pronoun is extended to the matrix clause (but no further). Extending this analysis to ìi pronouns would be incorrect in two respects: such an analysis incorrectly predicts that ìi disallows a local binder, while in fact ìi neither disallows nor requires a local binder; and the analysis provides no means of enforcing coreference with a more distant binder, as ìi requires.

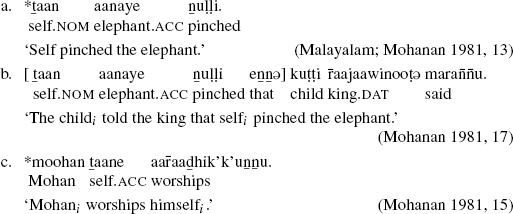

1.4 ìi is not a pronominal anaphor

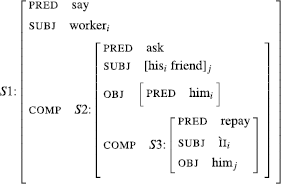

To ensure the presence of a nonlocal antecedent for ìi, we might attempt to state the binding requirements for ìi as a combination of a local noncoreference requirement (as we expect to find with pronominals) and a nonlocal coreference requirement (as we find with long-distance reflexives): that is, ìi would be an overt pronominal anaphor, which must be locally free but bound in a larger domain, as originally suggested for the Malayalam pronoun n̲taan by Mohanan (1981) or the Scandinavian pronoun seg by Hellan (1988) (see also Dalrymple 1993 and Kiparsky 2002). Mohanan (1981) provides examples (21a) and (21b) to show that n̲taan must be bound, and example (21c) to show that the binder of n̲taan may not be a coargument of the same predicate—that is, n̲taan must be bound within the sentence in which it appears, but may not be locally bound:

-

(21)

Such an approach does not produce the right result for ìi, however. We cannot ensure that the antecedent of ìi appears at least two clauses removed by requiring ìi to be free in the S2 domain but bound in the entire sentence, since ìi can appear whether or not there is a potential binder in the S2 domain.

Refining the condition to disallow particular types of binders in S2 does not help. Ya̧g Dii has three types of pronouns (mí,  , and bi, to be described in Sect. 2) that are in principle potential binders for ìi in S2. Since ìi must appear in a grammaticised logophoric domain and must corefer with the logophoric antecedent, any potential pronominal binder for ìi within the logophoric domain must also be a logophoric pronoun. As we will show in Sect. 3, the mí and

, and bi, to be described in Sect. 2) that are in principle potential binders for ìi in S2. Since ìi must appear in a grammaticised logophoric domain and must corefer with the logophoric antecedent, any potential pronominal binder for ìi within the logophoric domain must also be a logophoric pronoun. As we will show in Sect. 3, the mí and  series are antilogophoric, and cannot appear in the logophoric domain when coreferential with the logophoric antecedent. This leaves only bi as a potential binder for ìi in S2. In (10), repeated here, the subject of S2 is a bi-type pronoun, and there is no problem with coreference between the bi subject of S2 and the ìi subject of S3.

series are antilogophoric, and cannot appear in the logophoric domain when coreferential with the logophoric antecedent. This leaves only bi as a potential binder for ìi in S2. In (10), repeated here, the subject of S2 is a bi-type pronoun, and there is no problem with coreference between the bi subject of S2 and the ìi subject of S3.

-

(22)

2 The Ya̧g Dii pronominal system

The pronominal system of Ya̧g Dii is exceptionally complex, with four main classes of pronominal forms morphologically realised as independent pronouns, pronominal affixes, and verbal auxiliaries formed on pronominal bases.Footnote 5

ìi pronouns share some properties with  pronouns, which usually appear as subjects of subordinate clauses, and also share some other properties with bi pronouns. Here we provide a description of the pronominal system of Ya̧g Dii, situating the ìi pronouns in the overall system and demonstrating important commonalities and differences among the four classes of pronominal forms.

pronouns, which usually appear as subjects of subordinate clauses, and also share some other properties with bi pronouns. Here we provide a description of the pronominal system of Ya̧g Dii, situating the ìi pronouns in the overall system and demonstrating important commonalities and differences among the four classes of pronominal forms.

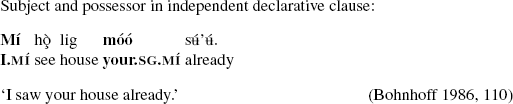

Following Bohnhoff (1986, 2010), we refer to the four main types as mí,  , bi, and ìi forms, named after the first person forms of each series. Their distribution is roughly as in Table 1.Footnote 6

, bi, and ìi forms, named after the first person forms of each series. Their distribution is roughly as in Table 1.Footnote 6

, bi, and ìi forms

, bi, and ìi formsLogophoric vs. nonlogophoric domain

A major division in the pronominal system is between what Bohnhoff calls the ‘nonlogophoric’ mí/ sets and the ‘logophoric’ bi/ìi sets. The bi/ìi sets appear only in a grammaticised logophoric domain or bi domain, and cannot be used for deictic reference. The bi domain is triggered by five types of subordinate clauses, including typical logophoric domains such as indirect speech as well as domains not usually associated with logophoricity, such as purpose clauses: bi pronouns are found in indirect quotations, indirect orders, subordinate desiderative clauses, affirmative purpose clauses, and causal adjuncts introduced by ka or bà (see Sect. 4 for more discussion of the logophoric domain and grammaticised logophoricity in Ya̧g Dii). Note that the bi domain includes both complement clauses (indirect quotations, indirect orders) and adjunct clauses (subordinate desiderative clauses, affirmative purpose clauses, and certain kinds of causal adjuncts). bi pronouns appear only within the bi domain, and must corefer with the subject of the clause that contains the bi domain (the ‘logophoric antecedent’): Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) refers to this as the reference condition or ref cond. The mí/

sets and the ‘logophoric’ bi/ìi sets. The bi/ìi sets appear only in a grammaticised logophoric domain or bi domain, and cannot be used for deictic reference. The bi domain is triggered by five types of subordinate clauses, including typical logophoric domains such as indirect speech as well as domains not usually associated with logophoricity, such as purpose clauses: bi pronouns are found in indirect quotations, indirect orders, subordinate desiderative clauses, affirmative purpose clauses, and causal adjuncts introduced by ka or bà (see Sect. 4 for more discussion of the logophoric domain and grammaticised logophoricity in Ya̧g Dii). Note that the bi domain includes both complement clauses (indirect quotations, indirect orders) and adjunct clauses (subordinate desiderative clauses, affirmative purpose clauses, and certain kinds of causal adjuncts). bi pronouns appear only within the bi domain, and must corefer with the subject of the clause that contains the bi domain (the ‘logophoric antecedent’): Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) refers to this as the reference condition or ref cond. The mí/ forms may also appear in the bi domain, but may not corefer with the logophoric antecedent when they appear there.

forms may also appear in the bi domain, but may not corefer with the logophoric antecedent when they appear there.

Subject vs. nonsubject pronoun forms

mí and bi pronominal forms can appear either as subjects or as nonsubjects.  and ìi forms appear only as subjects. Subject forms in all four types can encode future/nonfuture tense and declarative/imperative mood; they then appear in a fixed position after the full subject phrase and before the verb, in what Bohnhoff calls the PN-ML-TE (person-number-mood-logophoricity-tense-emphasis) position. Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) analyses these forms as tensed pronouns, noting that they are transparently related to the free pronoun sets in the case of the mí and bi pronouns, and Nordlinger and Sadler (2004a, 2004b) adopt the analysis of these forms as tensed pronouns in their discussion of nominal tense. Nordlinger and Sadler observe that it can be difficult to distinguish tensed pronoun forms from verbal auxiliaries with pronominal agreement marking, and point out that an analysis of such forms as tensed pronouns is best motivated for languages in which the relevant forms bear case, appear in multiple positions within the clause, and/or bear a grammatical function other than subject. In Ya̧g Dii, however, these forms cooccur with full pronominal and nonpronominal subject forms, always appear after the full subject phrase and before the verb, and do not bear case, suggesting that they are best analysed as verbal auxiliaries and not as tensed pronouns. Specifically, if we assume that clauses are best analysed as of category IP, these verbal auxiliary forms are of category I and head the IP phrase. In functional terms, the forms contribute tense and/or mood information at the clausal level as well as a pronominal subject with the binding properties appropriate to each type of pronoun.

and ìi forms appear only as subjects. Subject forms in all four types can encode future/nonfuture tense and declarative/imperative mood; they then appear in a fixed position after the full subject phrase and before the verb, in what Bohnhoff calls the PN-ML-TE (person-number-mood-logophoricity-tense-emphasis) position. Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) analyses these forms as tensed pronouns, noting that they are transparently related to the free pronoun sets in the case of the mí and bi pronouns, and Nordlinger and Sadler (2004a, 2004b) adopt the analysis of these forms as tensed pronouns in their discussion of nominal tense. Nordlinger and Sadler observe that it can be difficult to distinguish tensed pronoun forms from verbal auxiliaries with pronominal agreement marking, and point out that an analysis of such forms as tensed pronouns is best motivated for languages in which the relevant forms bear case, appear in multiple positions within the clause, and/or bear a grammatical function other than subject. In Ya̧g Dii, however, these forms cooccur with full pronominal and nonpronominal subject forms, always appear after the full subject phrase and before the verb, and do not bear case, suggesting that they are best analysed as verbal auxiliaries and not as tensed pronouns. Specifically, if we assume that clauses are best analysed as of category IP, these verbal auxiliary forms are of category I and head the IP phrase. In functional terms, the forms contribute tense and/or mood information at the clausal level as well as a pronominal subject with the binding properties appropriate to each type of pronoun.

A related issue is whether third person verbal auxiliaries must always be treated as contributing an incorporated third person pronoun; if they are, free pronominal and non-pronominal third person subjects must be treated as topics or appositions to such incorporated third person subject pronouns.Footnote 7 This corresponds to the distinction between what Bresnan and Mchombo (1987) call anaphoric agreement, involving an anaphoric relation between a topic or appositional phrase and an incorporated pronominal subject, and grammatical agreement. In their exploration of grammatical vs. anaphoric agreement in Chicheŵa, Bresnan and Mchombo (1987) demonstrate convincingly that the Chicheŵa third person object agreement morpheme is best treated as an incorporated pronoun (anaphoric agreement), while the subject agreement morpheme is ambiguously used for grammatical and anaphoric agreement. Austin and Bresnan (1996) provide a thorough discussion of grammatical and anaphoric agreement from a crosslinguistic perspective, demonstrating the necessity of treating many agreement morphemes as ambiguous between grammatical and anaphoric agreement.

In fact, the treatment of third person forms as anaphoric or grammatical agreement in the presence of a full noun phrase subject does not affect the analysis of the binding patterns we examine here, since bound pronouns do not cooccur with an overt full subject phrase in the clause. Hence, for clarity and consistency with Bohnhoff’s presentation of examples, we assume that all verbal auxiliaries contain incorporated subject pronouns which may show anaphoric agreement with other nominal phrases in the sentence. However, further research may reveal that the correct analysis of Ya̧g Dii third person forms involves ambiguity between grammatical and anaphoric agreement (as in Chicheŵa), if evidence is found that full third person noun phrases behave as subjects and not appositions in Ya̧g Dii.

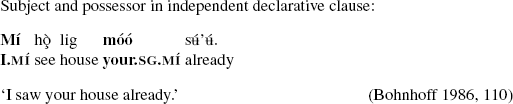

3 Nonlogophoric pronouns

The nonlogophoric pronouns mí and  are distinguished in terms of the syntactic environments in which they must appear: roughly,

are distinguished in terms of the syntactic environments in which they must appear: roughly,  pronouns appear in imperatives and in most types of subordinate clauses, while mí pronouns appear elsewhere, in non-imperative main clauses and in some types of subordinate clauses. They do not differ in binding requirements: neither mí pronouns nor

pronouns appear in imperatives and in most types of subordinate clauses, while mí pronouns appear elsewhere, in non-imperative main clauses and in some types of subordinate clauses. They do not differ in binding requirements: neither mí pronouns nor  pronouns require a binder, and both are antilogophoric when appearing in the grammaticised logophoric domain.

pronouns require a binder, and both are antilogophoric when appearing in the grammaticised logophoric domain.

A partial paradigm for the mí and  nonlogophoric pronominal forms is given in Table 2. The discontinuous 1incl.pl forms (e.g. ba…ví) can be interrupted by the verbal complex (the verb or series of serial verbs and any object pronouns). There are additional emphatic and possessive mí forms not listed here, as well as portmanteau forms of the verbal auxiliaries incorporating a complementizer; see Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) for the full paradigms. There are no nonsubject

nonlogophoric pronominal forms is given in Table 2. The discontinuous 1incl.pl forms (e.g. ba…ví) can be interrupted by the verbal complex (the verb or series of serial verbs and any object pronouns). There are additional emphatic and possessive mí forms not listed here, as well as portmanteau forms of the verbal auxiliaries incorporating a complementizer; see Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) for the full paradigms. There are no nonsubject  forms. For present purposes, it is sufficient to distinguish the members of the mí and

forms. For present purposes, it is sufficient to distinguish the members of the mí and  series listed in Table 2, and in fact we will mainly be concerned with the four-way distinction in distribution involving the subject mí,

series listed in Table 2, and in fact we will mainly be concerned with the four-way distinction in distribution involving the subject mí,  , bi, and ìi forms.

, bi, and ìi forms.

In examples (23)–(26), the mí subject, object, and possessive pronouns are used:

-

(23)

-

(24)

-

(25)

In contrast, examples (26) and (27) require  subject pronouns (there are no

subject pronouns (there are no  nonsubject pronouns).

nonsubject pronouns).

-

(26)

-

(27)

mí and  subject forms appear in the environments listed in Table 3:

subject forms appear in the environments listed in Table 3:  pronouns are required as the subject of imperatives and many types of subordinate clauses, while mí pronouns appear elsewhere. Beyond these tendencies, there does not seem to be any unifying synchronic generalization governing the environments in which either form appears; clauses requiring

pronouns are required as the subject of imperatives and many types of subordinate clauses, while mí pronouns appear elsewhere. Beyond these tendencies, there does not seem to be any unifying synchronic generalization governing the environments in which either form appears; clauses requiring  subjects must simply be marked as such in the synchronic grammar.

subjects must simply be marked as such in the synchronic grammar.

subject forms (Bohnhoff 2010, 89)

subject forms (Bohnhoff 2010, 89)The set of clauses requiring  subjects do not share properties of subordination, tense, mood, morphological marking, grammatical role, or binding relations involving the subject of the clause. First, the distinction between mí-clauses and

subjects do not share properties of subordination, tense, mood, morphological marking, grammatical role, or binding relations involving the subject of the clause. First, the distinction between mí-clauses and  -clauses cannot be defined in terms of subordination: though the

-clauses cannot be defined in terms of subordination: though the  -clause is often a subordinate clause, the

-clause is often a subordinate clause, the  form is required as the main clause subject in imperatives, as shown in example (26). Second, there are no special tense, mood, or morphological attributes which distinguish

form is required as the main clause subject in imperatives, as shown in example (26). Second, there are no special tense, mood, or morphological attributes which distinguish  from mí clauses. Third, the mí/

from mí clauses. Third, the mí/ distinction does not correspond to the argument/adjunct distinction: both mí and

distinction does not correspond to the argument/adjunct distinction: both mí and  can be subjects of complement clauses (indirect quotations for mí, indirect orders for

can be subjects of complement clauses (indirect quotations for mí, indirect orders for  ) as well as adjunct clauses (for example, comparison clauses and manner adjuncts for mí, relative clauses and causal adjuncts for

) as well as adjunct clauses (for example, comparison clauses and manner adjuncts for mí, relative clauses and causal adjuncts for  ).

).

Fourth, the choice between mí and  forms does not depend on binding relations with other elements in the sentence. Both mí and

forms does not depend on binding relations with other elements in the sentence. Both mí and  are antilogophoric, and may not be bound by the logophoric antecedent within the logophoric domain. In nonlogophoric domains,

are antilogophoric, and may not be bound by the logophoric antecedent within the logophoric domain. In nonlogophoric domains,  forms may appear with or without a binder in the same sentence, and with or without a binder in the immediately higher clause. In (28), the subject of the relative clause is an

forms may appear with or without a binder in the same sentence, and with or without a binder in the immediately higher clause. In (28), the subject of the relative clause is an  pronoun, and there is no other phrase coreferent with it in the sentence:

pronoun, and there is no other phrase coreferent with it in the sentence:

-

(28)

The grammatical structure of example (28) is shown in (29):

-

(29)

In (30), the  form appears as the subject of an adjunct clause within the clausal complement of the main verb say. In this example,

form appears as the subject of an adjunct clause within the clausal complement of the main verb say. In this example,  does not have a binder in the immediately higher clause, though it is coreferent with an argument in the main clause:

does not have a binder in the immediately higher clause, though it is coreferent with an argument in the main clause:

-

(30)

Example (31) is structurally similar to (30), but the coreference relations are different. The  subject of the most embedded verb, return, corefers with the

subject of the most embedded verb, return, corefers with the  subject of cook in the immediately higher clause as well as with a nonsubject in the main clause:

subject of cook in the immediately higher clause as well as with a nonsubject in the main clause:

-

(31)

The grammatical structure of examples (30) and (31) is shown in (32):

-

(32)

In examples (30) and (31), the  pronoun precedes the subject of the immediately higher clause, and may but need not be bound by it. The same is true if the order is reversed: in examples (33) and (34), the

pronoun precedes the subject of the immediately higher clause, and may but need not be bound by it. The same is true if the order is reversed: in examples (33) and (34), the  pronoun follows the subject of the immediately higher clause, and coreference is allowed but not required. Coreference with the immediately higher subject obtains in example (33), in which the

pronoun follows the subject of the immediately higher clause, and coreference is allowed but not required. Coreference with the immediately higher subject obtains in example (33), in which the  pronoun is the subject of a relative clause. In contrast, in example (34) the

pronoun is the subject of a relative clause. In contrast, in example (34) the  pronoun is the subject of a subordinate desiderative clause, and does not corefer with the subject of the main clause.

pronoun is the subject of a subordinate desiderative clause, and does not corefer with the subject of the main clause.

-

(33)

-

(34)

Thus,  can appear with no binder, or with a binder in the same sentence, which may but need not be in the immediately higher clause.

can appear with no binder, or with a binder in the same sentence, which may but need not be in the immediately higher clause.

The mí/ distinction might be thought of as similar to a specialised case-marking requirement for

distinction might be thought of as similar to a specialised case-marking requirement for  subjects of a certain class of clauses. This is reminiscent of the requirement for genitive subjects of nominalised subordinate clauses in some languages; Givón (2009) provides the following examples of this pattern from Ute (Numic, Uto-Aztecan):

subjects of a certain class of clauses. This is reminiscent of the requirement for genitive subjects of nominalised subordinate clauses in some languages; Givón (2009) provides the following examples of this pattern from Ute (Numic, Uto-Aztecan):

-

(35)

-

(36)

However, this explanation does not extend to Ya̧g Dii, since there is no morphological evidence that  -clauses are nominalized, or that

-clauses are nominalized, or that  pronouns are genitive: the Ya̧g Dii possessive pronoun paradigm is distinct from the subject mí and

pronouns are genitive: the Ya̧g Dii possessive pronoun paradigm is distinct from the subject mí and  paradigms, as shown in Table 2.

paradigms, as shown in Table 2.

4 bi pronouns

According to what Bohnhoff (1986, 112) calls the reference condition, bi pronouns appear at any depth of embedding within a restricted set of subordinate clauses, the grammaticised logophoric domain or bi domain, labelled S2 in Sect. 1. Within the bi domain, bi pronouns must be bound by the ‘logophoric antecedent’, the grammatical subject of the clause immediately containing the bi domain; if noncoreference with the logophoric antecedent is intended, the corresponding mí or  pronoun is used instead.

pronoun is used instead.

Table 4 presents the unmarked, nonfuture, and future forms of the logophoric bi series, and provides a comparison of nonlogophoric mí and logophoric bi non-auxiliary forms. The mí,  , and bi pronouns can all appear as subjects in the bi domain, and mí and bi pronouns can appear as nonsubjects. See Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) for the complete paradigm for the bi series, including emphatic forms.

, and bi pronouns can all appear as subjects in the bi domain, and mí and bi pronouns can appear as nonsubjects. See Bohnhoff (1986, 2010) for the complete paradigm for the bi series, including emphatic forms.

Within the bi domain S2, the bi pronoun is used when coreference with the logophoric antecedent is intended; when noncoreference is intended, the nonlogophoric mí or  forms must be used. In (37), the bi domain is the subordinate clause they go to town, and the antecedent of bi is the subject of the matrix verb want:

forms must be used. In (37), the bi domain is the subordinate clause they go to town, and the antecedent of bi is the subject of the matrix verb want:

-

(37)

In example (38), coreference between the matrix and complement subject is not intended, and the bi pronoun cannot be used. Since the subordinate clause is an indirect order, which is an  -type clause, the

-type clause, the  pronoun is used:

pronoun is used:

-

(38)

Thus, in a bi domain, use of a nonlogophoric pronoun produces an antilogophoric effect: here, the  pronoun may not corefer with the logophoric antecedent. The antilogophoric effect holds only within the bi domain, and only relative to the bi antecedent; the

pronoun may not corefer with the logophoric antecedent. The antilogophoric effect holds only within the bi domain, and only relative to the bi antecedent; the  pronoun may in general be used in a subordinate clause to corefer with the immediately higher subject, as long as noncoreference with the logophoric antecedent is maintained. The antilogophoric effect is shown in example (31), whose grammatical structure is shown in (32).

pronoun may in general be used in a subordinate clause to corefer with the immediately higher subject, as long as noncoreference with the logophoric antecedent is maintained. The antilogophoric effect is shown in example (31), whose grammatical structure is shown in (32).

The bi domain is triggered by clauses of various types: indirect quotations, indirect orders, subordinate desiderative clauses, affirmative purpose clauses, and causal adjuncts introduced by ka or bà. Some of these are typical domains associated with logophoricity, but in fact a purely semantic or pragmatic characterisation of binding requirements for bi is not possible. Culy (1997) discusses the extension of logophoric marking from standard logophoric complements to adjuncts such as purpose clauses and causal clauses, and proposes that this is the result of grammaticisation of an original logophoric system (see also Hyman and Comrie 1981); this seems to be the case for Ya̧g Dii. Thus, as with  -clauses, the bi domain must be syntactically marked as such, and cannot be defined in purely semantic terms. We discuss morphosyntactic commonalities in different types of bi domains below.

-clauses, the bi domain must be syntactically marked as such, and cannot be defined in purely semantic terms. We discuss morphosyntactic commonalities in different types of bi domains below.

There are several pieces of evidence that Ya̧g Dii exhibits grammaticised logophoricity, and that neither the bi domain nor the antecedent of bi can be defined in purely semantic terms. First, the antecedent of a true logophoric pronoun is the individual “whose speech, thoughts, feelings, or general state of consciousness are reported” (Clements 1975; see also Sells 1987): the antecedent is identified through semantic and pragmatic means, not syntactically. In Ya̧g Dii, however, the antecedent of a bi pronoun must be a subject, and nonsubject antecedents are not permitted. This is also the case in other partially grammaticised logophoric systems, including Icelandic (Sells 1987; Bresnan 2001).

Second, Schlenker (2003) observes that “a logophoric element should not be allowed to denote the speaker of the actual speech act”, meaning that there should be no first person forms of true logophoric pronouns. As seen in Table 4, however, bi pronouns instantiate the full pronominal paradigm, including first person forms.

Third, typical logophoric domains encode reported speech, thought, or perception, but the bi domain includes additional types of subordinate clauses such as purpose clauses or causal constructions (see Culy 1997, for discussion of similar patterns in other grammaticised logophoric systems). Indeed, not all causal constructions trigger a bi domain, but only those that are marked by particular complementizers: causal constructions introduced by ka/bà constitute a bi domain (example (42)), while causal constructions with moo, as in example (39), do not:

-

(39)

The mí pronoun is used as the subject of the subordinate clause because they said that he’s crazy because this is neither a bi domain nor a  -clause: only causal constructions with ka/bà allow bi or

-clause: only causal constructions with ka/bà allow bi or  pronouns, not causal constructions with moo.

pronouns, not causal constructions with moo.

There is an interesting overlap between the bi domain and clauses that require  subjects. As shown by the contrast between examples (37) and (38), certain clauses require

subjects. As shown by the contrast between examples (37) and (38), certain clauses require  subjects and also constitute a bi domain: in subject position of such clauses, the bi pronoun is used for coreference with the matrix subject, while the antilogophoric properties of the

subjects and also constitute a bi domain: in subject position of such clauses, the bi pronoun is used for coreference with the matrix subject, while the antilogophoric properties of the  pronoun require noncoreference. The different clause types are summarized in Table 5.

pronoun require noncoreference. The different clause types are summarized in Table 5.

subjects and clauses constituting a bi domain

subjects and clauses constituting a bi domainBohnhoff provides example (40) to show that the bi pronoun must be bound by the closest eligible binder. The verbs say and tell both introduce a bi domain, since their complements are indirect quotations. However, example (40) is not ambiguous; the antecedent of the bi pronoun must be Moses, the closest eligible bi antecedent, and not Mother:Footnote 8

-

(40)

In example (41), the first person feature of the closest logophoric antecedent does not match the third person feature of the bi pronoun, and the result is ungrammaticality:

-

(41)

Unlike the  pronoun, whose appearance is restricted to subject position, the bi pronoun may appear as a subject, object, or possessor within the bi domain. In example (42), the object of the subordinate verb refuses is a bi pronoun whose antecedent is the subject of the matrix verb attack:

pronoun, whose appearance is restricted to subject position, the bi pronoun may appear as a subject, object, or possessor within the bi domain. In example (42), the object of the subordinate verb refuses is a bi pronoun whose antecedent is the subject of the matrix verb attack:

-

(42)

In example (43), both the subordinate subject and the possessor of the object are bi pronouns:

-

(43)

Morphosyntactically, the bi domain is usually marked either by the subordinator/complementiser bà or by the presence of a particular lexical predicate in the immediately higher clause; Culy (1997) discusses the importance of marking by particular complementisers in defining the logophoric domain in many languages. Subordinate affirmative purpose clauses seem to constitute an exception to this generalisation, since they do not contain special marking to indicate the bi domain, and need not appear with a particular predicate in the immediately higher clause; these may be positionally encoded.

-

(44)

Example (37) contains a subordinate desiderative clause, signaled by the presence of the verb ‘want’ in the matrix clause. Example (42) contains a causal adjunct with the subordinator/complementiser bà. Indirect quotations are also introduced by bà:

-

(45)

In fact, indirect discourse may consist of a number of clauses, as in (46):

-

(46)

Each clause in these multi-clause indirect discourse segments is marked with the subordinator/complementiser bà, thus conforming to the syntactic criteria defining a bi domain, and contains a bi pronoun that is coreferent with the logophoric antecedent ‘our elder’. Bresnan (2001) provides an extensive discussion of binding of logophoric pronouns and partially or completely grammaticised logophoric systems in Icelandic, Ewe, Latin, and other languages, noting that even in languages with grammaticised logophoricity, logophoric pronouns can often appear in extended indirect discourse, as in the Ya̧g Dii example (46). Following Bohnhoff (2010, 209), we analyse these examples as subordination to an unpronounced main clause predicate, with only the subordinate bi domain realised. An alternative analysis might treat these in terms of a morphologically marked main-clause bi domain interpreted as indirect discourse (see Dimmendaal 2001 for more discussion). For uniformity, and in the absence of evidence that the conditions governing these multi-clause examples are different from the other examples, we assume that subordination is involved, with an unpronounced main-clause predicate. In either case, with the presence of the complementizer bà, the syntactic criteria defining the bi domain are met in these cases as well, even in the absence of an explicit main clause predicate.

5 Subordinate clause logophoric pronouns: ìi

Our primary interest is a fourth series of pronouns which we label ìi, shown in Table 6 and characterised above as the “exclusively long-distance” series. Like the bi series, ìi pronouns cannot be used deictically: they appear in the bi domain and must corefer with the logophoric antecedent. In some contexts, in fact, either the bi or the ìi pronoun may appear: “Initial concessive and cause clauses for many speakers simply retain the bi forms, although some examples of ìi may also be heard” (Bohnhoff 1986, 121). However, ìi pronouns are unlike bi pronouns in that they must appear as the subject of an embedded clause (S3) within the logophoric domain (S2), and must corefer with the logophoric antecedent (the subject of S1), at least two clauses distant. Further, as shown in examples (8) and (10), the ìi pronoun neither requires nor disallows a coreferential pronoun in the intervening clause in the bi domain; ìi ignores potential binders in S2, requiring the subject of S1 as its binder. ìi is, then, an exceptionally long-distance anaphor, whose binding conditions seem to be exclusively nonlocal.

Besides sharing binding properties with bi, the ìi series is also similar in distribution and, in some cases, in morphological shape to the  series; indeed, Bohnhoff (1986, 123) states that “in the same way that

series; indeed, Bohnhoff (1986, 123) states that “in the same way that  subjects are used instead of mí subjects in certain clauses, so ìi subjects occur instead of bi subjects in (some of) those same grammatical contexts”. Both ìi and

subjects are used instead of mí subjects in certain clauses, so ìi subjects occur instead of bi subjects in (some of) those same grammatical contexts”. Both ìi and  pronouns are used only in subject position of certain subordinate clauses within the bi domain; there are no ìi object or possessive pronouns. The subordinate environments in which the

pronouns are used only in subject position of certain subordinate clauses within the bi domain; there are no ìi object or possessive pronouns. The subordinate environments in which the  series must appear were given in Table 3 and are repeated here:

series must appear were given in Table 3 and are repeated here:

-

(47)

Subordinate clauses with

subjects: indirect order, temporal/locative/conditional adjunct, concessive clause, affirmative purpose clause, causal adjunct introduced by ka or bà, relative clause, desiderative clause (Bohnhoff 2010, 89)

subjects: indirect order, temporal/locative/conditional adjunct, concessive clause, affirmative purpose clause, causal adjunct introduced by ka or bà, relative clause, desiderative clause (Bohnhoff 2010, 89)

A very similar list of subordinate clauses require ìi subjects within the logophoric domain: ìi pronouns are attested as the subject of an indirect order (example (16)), in temporal/locative/conditional adjunct clauses (examples (10) and (48)), concessive clauses (example (8)), affirmative purpose clauses, causal adjuncts, and relative clauses (example (2)).

-

(48)

Given this, it is tempting to analyse ìi as just the logophoric version of  : ìi pronouns appear in subject position of (most)

: ìi pronouns appear in subject position of (most)  clauses, just like

clauses, just like  pronouns, and are bound by the logophoric antecedent, just like bi pronouns. This seems to give the correct result in many cases. However, examination of cases of overlap between the

pronouns, and are bound by the logophoric antecedent, just like bi pronouns. This seems to give the correct result in many cases. However, examination of cases of overlap between the  and bi domains, shown in Table 5, reveals problems with this proposal. The complement of the verb want is an indirect order: indirect orders require

and bi domains, shown in Table 5, reveals problems with this proposal. The complement of the verb want is an indirect order: indirect orders require  subjects, and are also a bi domain.

subjects, and are also a bi domain.  pronouns (ex. (49a)) as well as logophoric bi pronouns (ex. (49b)) appear in this domain. If ìi were simply required to appear in a

pronouns (ex. (49a)) as well as logophoric bi pronouns (ex. (49b)) appear in this domain. If ìi were simply required to appear in a  clause and to be bound by the logophoric antecedent, we would expect the ìi pronoun and not the bi pronoun in this environment. This is not possible, however, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (49c). In contrast, if the logophoric antecedent is sufficiently far away, the ìi pronoun is acceptable as the subject of a purpose clause, as shown in (49d).

clause and to be bound by the logophoric antecedent, we would expect the ìi pronoun and not the bi pronoun in this environment. This is not possible, however, as shown by the ungrammaticality of (49c). In contrast, if the logophoric antecedent is sufficiently far away, the ìi pronoun is acceptable as the subject of a purpose clause, as shown in (49d).

-

(49)

The ìi pronoun is similarly unacceptable in examples (50c) and (51c), where ìi is in a bi domain and is the subject of an  clause, since there is no antecedent for ìi that is sufficiently far away in these cases:

clause, since there is no antecedent for ìi that is sufficiently far away in these cases:

-

(50)

-

(51)

These examples cannot be accounted for in terms of a noncoreference requirement between the ìi pronoun and the next subject up, since, as shown in examples (10) and (48), coreference between ìi and the next subject up is in fact possible.

It is also not possible to get around this problem by claiming that a clause must be either a logophoric bi clause or a nonlogophoric  clause, but not both at once. This would lead to the prediction that bi and

clause, but not both at once. This would lead to the prediction that bi and  pronouns cannot appear in the same clause, but this prediction is incorrect: example (52) shows that bi and

pronouns cannot appear in the same clause, but this prediction is incorrect: example (52) shows that bi and  pronouns can appear in the same clause.

pronouns can appear in the same clause.

-

(52)

In sum, ìi is an exclusively long-distance anaphor, and its antecedent must appear at least two clauses away.

6 Summary: Distributions of the Ya̧g Dii pronouns

The following generalisations govern the distribution of the four types of Ya̧g Dii pronouns:

-

(53)

- mí::

-

can bear any grammatical function, except for subject of

clause; antilogophoric in bi domain

clause; antilogophoric in bi domain -

::

:: -

must appear as subject of

clause; antilogophoric in bi domain

clause; antilogophoric in bi domain - bi::

-

appears only in bi domain; can bear any grammatical function (except for some subordinate subject positions within bi domain); coreferent with logophoric antecedent

- ìi::

-

appears only as subordinate subject within logophoric domain; coreferent with logophoric antecedent

The status of the parenthesised portion of the condition on bi reflects the uncertainty discussed at the beginning of the previous section: in at least some clauses within the bi domain, either bi or ìi can appear, but it is not clear whether the bi and ìi pronouns are in free variation in all  -type clauses in the bi domain.

-type clauses in the bi domain.

7 Binding in lexical functional grammar

7.1 Background assumptions

Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) assumes that different aspects of the structure of sentences of natural language are represented by different formal structures which are related to one another by principles of correspondence. The constituent structure or c-structure represents word order, phrasal grouping, and phrasal dominance relations, and the functional structure or f-structure represents grammatical functions and relations such as control.

In the foregoing, we have presented abbreviated functional structures as an aid to understanding the syntactic relation between a pronoun and its antecedent. We have used the f-structure to depict these syntactic relations because it is this structure that is of crucial importance in the statement of binding relations (Dalrymple 1993; Bresnan 2001; Asudeh 2004, 2012). LFG’s binding theory assumes that binding relations are properly stated in terms of functional relations such as subject and object, relations that are native to f-structure. Pronouns may require a subject as binder, for example, or may allow a binder bearing any grammatical function, so long as the structural superiority relation between a pronoun and its antecedent is met. Crosslinguistically, the domain in which a pronoun must be bound or free is also defined in terms of f-structural concepts, specifically predicate, subject, and tense. These three concepts each correspond to some syntactically or semantically “complete” entity: a saturated proposition involving a predicate and its arguments, a predication involving some property and a subject, and a temporally anchored proposition, respectively (Dalrymple 1993). We will see that binding in Ya̧g Dii requires reference to an additional feature defining the logophoric domain.

Another central tenet of LFG’s binding theory is that binding requirements are specified lexically rather than on a universal or language-by-language basis. This is clear in the analysis of languages with more than one reflexive, such as Norwegian or Marathi (Dalrymple 1993): if a language has more than one reflexive, each obeying a different set of binding constraints, it is not possible to state binding constraints for reflexives for the language as a whole. As we have seen, the logophoric and nonlogophoric pronouns in Ya̧g Dii obey different constraints on where they can appear and where they must be bound, and so it is necessary to specify binding constraints lexically, and associate the appropriate constraints with each type of pronoun.

7.2 Binding in LFG

LFG provides a precise formal vocabulary for the statement of universally available binding requirements. According to LFG’s binding theory, binding requirements are stated in terms of binding equations like the schematic equation shown in (54), where ↑ is the f-structure of the pronoun, ↑ σ is the semantic structure corresponding to ↑, and (↑ σ ant) refers to the antecedent of the pronoun. According to the equation in (54), the antecedent must be found within the binding domain (gf ∗ gf pro ↑), and the antecedent bears the grammatical function gf ant within this domain:Footnote 9

-

(54)

The f-structural relation between the antecedent and the pronoun is shown in (55):

-

(55)

The outermost f-structure in (55) is the binding domain, within which both the pronoun and its binder must appear. The general form of the binding equation in (54) derives the requirement for the antecedent to command the pronoun: the antecedent must appear at the end of the singleton path gf ant, while the pronoun appears embedded within the binding domain, at the end of a possibly longer path.

Binding equations for particular pronouns are further specialised to encode binding domains delimited by the attributes pred (which marks the domain of a predicate and its arguments), subj (which marks a domain of predication involving a subject), and tense (which marks the domain of a temporally anchored proposition). This is accomplished by the use of off-path constraints, which encode constraints on f-structures which may contain the pronoun and its binder. For example, the binding equation in (56) uses the off-path constraint ¬(→ tense) to require the pronoun to find its antecedent in the minimal finite domain containing the pronoun; the off-path constraint has a limiting effect on the pronoun’s search for an antecedent, preventing the path through the binding domain from passing through an f-structure with the attribute tense:

-

(56)

Binding equations for all types of pronouns are specified as in (54), with a singleton path gf ant within the binding domain determining the antecedent of the pronoun, and a path of length one or more to the pronoun. As such, LFG’s binding constraints conform to the Locality Condition for anaphoric binding (“binding constraints … always refer to local elements, never exclusively to nonlocal ones”: Dalrymple 1993). Since the binding domain is defined in terms of a path of one or more grammatical functions (gf ∗ gf pro), local elements are always included in consideration as potential antecedents. Of course, some local elements may be ineligible as antecedents for particular pronouns because of additional requirements associated with the pronoun: for instance, particular pronouns may require the antecedent to be not only a local element, but also a subject. We will see examples of this below, where the attribute log is important in determining antecedenthood for bi and ìi pronouns. Importantly, LFG’s binding theory disallows the specification of a longer path which ignores local elements and requires the antecedent to appear at least two clauses away; encoding such a requirement would require specification of a path of length two or more, and this is not allowed.

8 The bi requirement

In order to constrain the distribution of the four types of Ya̧g Dii pronouns, we introduce an additional binding feature which is relevant for logophoric binding. We propose that the bi domain is marked log +, and we add the log feature to the inventory of features that are universally available to constrain the binding domain. Such a feature is necessary in the analysis of logophoric binding not only in Ya̧g Dii, but in other languages with grammaticised logophoricity as well: it is directly related to the ±log binding feature proposed by Bresnan (2001) in her discussion of logophoric binding, and is compatible with Strahan’s (2009, 2011) discussion of f-structural marking of the ‘perspective holder’ in logophoric binding, though it differs formally from Strahan’s proposal in that it does not impose the problematic requirement for the logophoric antecedent to control the search for any pronouns that it might be required to bind. It is also similar to the logophoric feature proposed by Asudeh (2009), which appears on all structures within the entire logophoric domain, though under Asudeh’s analysis, unlike the current proposal, it is difficult to capture the requirement for bi pronouns to be bound by the closest logophoric antecedent. In a different analytical tradition, it is similar in spirit to the null logophoric operator which binds logophoric pronouns in Adesola’s (2006) analysis of Yoruba (Niger-Congo) (see also Koopman and Sportiche 1989) though it differs in that the log feature is not itself the binder of the pronoun: it merely marks the matrix clause of the logophoric domain in which the logophoric pronoun must appear.

In Ya̧g Dii, the presence of the log feature is enforced by the predicate or construction which defines the logophoric domain (the main clause predicate whose complement is an indirect quotation, subordinate desiderative, or indirect order; the ka or ba marking on causal adjuncts; or the phrase structure rule marking a subordinate clause as a purpose clause). In (57), gf log is an abbreviation which stands for any of the grammatical functions that the logophoric domain may bear: often, this will be comp, the grammatical function of sentential complements. Clauses constituting a logophoric domain S2 appear as the value of gf log, and are marked as log +:

-

(57)

We can now state the requirements associated with the bi pronouns by reference to the feature log:

-

(58)

The form of the logophoric binding equation is different from the nonlogophoric binding equation given in (54), because in this case it is important to identify the logophoric domain (the f-structure marked with the log feature). In (58), the logophoric domain is the f-structure value of the gf log feature, and the logophoric pronoun must appear within that domain. The numbers under each element of the binding equation cross-reference the position in which the following constraints are imposed:

-

1.

Logophoric domain: the logophoric domain must be marked as such. Formally, the value of the attribute gf log, labelled S2 in (57), must be marked with the log attribute.

-

2.

Logophoric domain: the bi pronoun may be embedded at an arbitrary depth within the logophoric domain, but it must be bound by the closest logophoric binder: see the discussion of examples (40)–(41) for evidence that the smallest bi domain must be chosen). Formally, the path through the binding domain to the bi pronoun may not pass through another clause with log marking.

-

3.

Subjecthood of antecedent: the antecedent of the pronoun is the subj of S1, the clause containing the logophoric domain.

This combination of constraints encodes the binding requirements for the bi pronoun; importantly, it adheres to the generalisation that binding requirements are specified purely locally, and does not require a path of length two or more.

9 The  requirement

requirement

The  series of pronouns must appear as the subject of the clause types listed in Table 3. As we have noted, this is not a binding requirement, but a requirement constraining the form of the subject pronoun for the relevant types of clauses. There seems to be no independent syntactic criterion by which

series of pronouns must appear as the subject of the clause types listed in Table 3. As we have noted, this is not a binding requirement, but a requirement constraining the form of the subject pronoun for the relevant types of clauses. There seems to be no independent syntactic criterion by which  clauses can be identified:

clauses can be identified:  clauses must simply be marked as such. We accomplish this by marking the subject of

clauses must simply be marked as such. We accomplish this by marking the subject of  clauses with an +.

clauses with an +.

-

(59)

pronouns are marked with an existential constraint requiring the presence of the an feature, as shown in (60), while mí pronouns are incompatible with that feature.

pronouns are marked with an existential constraint requiring the presence of the an feature, as shown in (60), while mí pronouns are incompatible with that feature.

-

(60)

Constraint on

forms, requiring the presence of the an feature: (↑ an)

forms, requiring the presence of the an feature: (↑ an)

10 Constraints on ìi

By appealing to the an and bi features which we have already introduced, we can capture the commonalities in binding requirements between  and ìi, and between bi and ìi, by requiring ìi to obey the

and ìi, and between bi and ìi, by requiring ìi to obey the  requirements as well as the bi requirements. In (61), we associate ìi pronouns with the same existential constraint requiring the an features as for the

requirements as well as the bi requirements. In (61), we associate ìi pronouns with the same existential constraint requiring the an features as for the  pronouns (line 1 in (61)), and the same binding equation as for the bi pronouns (line 2 in (61)). Simply combining the two constraints, as in (61), is almost but not quite sufficient to encode the binding constraints which are relevant for ìi:

pronouns (line 1 in (61)), and the same binding equation as for the bi pronouns (line 2 in (61)). Simply combining the two constraints, as in (61), is almost but not quite sufficient to encode the binding constraints which are relevant for ìi:

-

(61)

This combination of constraints correctly allows ìi to appear in arbitrarily deeply embedded  -clauses within the logophoric domain S2, but also incorrectly allows it in non-embedded clauses in S2 (recall our discussion of examples (49)–(51) above).

-clauses within the logophoric domain S2, but also incorrectly allows it in non-embedded clauses in S2 (recall our discussion of examples (49)–(51) above).

To disallow ìi as the subject of S2, we must impose an additional requirement preventing the ìi pronoun from appearing in the highest clause within the logophoric domain: this is the clause that bears log + marking. In other words, ìi cannot appear in a log-marked clause. The final version of the binding constraints for ìi are given in (62):

-

(62)

As in (61), the first two lines of (62) duplicate the requirements for  (ìi must appear as the subject of an

(ìi must appear as the subject of an  -type clause) and for bi (ìi must be bound within the logophoric domain, and by the logophoric antecedent). The third line is new, and unique to ìi: ìi may not appear as the subject of a log-marked clause.

-type clause) and for bi (ìi must be bound within the logophoric domain, and by the logophoric antecedent). The third line is new, and unique to ìi: ìi may not appear as the subject of a log-marked clause.

On this analysis, the nonlocal nature of ìi’s binding requirements is captured by means of the same feature that governs the distribution of bi, and in keeping with the general form of LFG’s binding equations. The binding requirements for ìi are surprising and complicated: ìi must appear embedded at an arbitrary depth in a domain marked with the log feature (the second line of (62)) but may not appear as the subject of the highest clause in the logophoric domain, the clause marked with the log feature (the third line of (62)). Thus, it may only appear in embedded subject position within the logophoric domain. It is not the long-distance nature of the binding requirements associated with ìi that makes it an unusual anaphor, but the seemingly contradictory requirements that it must obey: it both requires log-marking in an expanded domain (line 2), and disallows it in a local domain (line 3). We do not encode binding constraints on ìi by means of a path requiring a distance of two or more clauses between a pronoun and its antecedent, because this would require nonlocal specification of binding requirements, and this is not allowed by LFG’s binding theory. Our analysis achieves a local specification of constraints on an apparently exclusively nonlocal relation.

11 Conclusion

Ya̧g Dii presents a complicated picture for theories of anaphoric binding. The distributions of the mí,  , and bi pronouns are not unexpected, given standard locality constraints on LFG’s binding equations and the ability to mark domains with information about their syntactic properties. We have proposed that the distribution of the ìi pronoun can be stated in local terms by reference to a log feature, which is independently motivated for Ya̧g Dii’s bi pronouns as well as for logophoric pronouns more generally. Our analysis achieves a purely local specification of the binding requirements for ìi, preserving the generalisation that grammars do not impose nonlocal grammatical constraints, and predicts the nonexistence of other possibilities—for example, a hypothetical anaphor that must appear at least three clauses removed from its antecedent.

, and bi pronouns are not unexpected, given standard locality constraints on LFG’s binding equations and the ability to mark domains with information about their syntactic properties. We have proposed that the distribution of the ìi pronoun can be stated in local terms by reference to a log feature, which is independently motivated for Ya̧g Dii’s bi pronouns as well as for logophoric pronouns more generally. Our analysis achieves a purely local specification of the binding requirements for ìi, preserving the generalisation that grammars do not impose nonlocal grammatical constraints, and predicts the nonexistence of other possibilities—for example, a hypothetical anaphor that must appear at least three clauses removed from its antecedent.

Notes

The pronoun vʉ ‘them’ in the relative clause is a resumptive pronoun.

This is a simplification; for detailed discussion of binding constraints for Chinese ziji, see Huang and Tang (1991) and references cited there.

We set aside a fifth class of ‘hypothetical’ verbal auxiliaries which are morphologically similar to the mí verbal auxiliaries; see Bohnhoff (2010) for discussion of this class.

Bohnhoff (2010) uses the term “factative” for what we call “declarative” in the following. The term “factative” is commonly used in descriptions of West African languages for the unmarked form signaling past or perfect tense for nonstative clauses and present tense for stative clauses (Welmers 1973), but Bohnhoff (2010) uses the term for both perfective and imperfective declarative clauses, distinguishing factative from imperative and hypothetical mood.

Thanks to Lee Bohnhoff for extensive discussion of this issue, and for important observations about differences between grammatical and anaphoric agreement in first and second vs. third person forms.

Example (40) also shows that the clause containing the logophoric domain, S1 in Sect. 1, can itself be embedded.

The symbol gf is an abbreviation defined as a disjunction over members of the set of grammatical functions (subj, obj, comp, …): that is, it is any grammatical function. The superscript asterisk (gf ∗) is the Kleene star, which allows zero or more occurrences of gf.

References

Adesola, Oluseye Peter. 2006. A-bar dependencies in the Yoruba reference-tracking system. Lingua 116: 2068–2106.

Asudeh, Ash. 2004. Resumption as resource management. PhD thesis, Stanford University.

Asudeh, Ash. 2009. Reflexives in the correspondence architecture, http://users.ox.ac.uk/~cpgl0036/slides/asudeh-iceland09-reflexives.pdf, slides of a talk presented at the University of Iceland.

Asudeh, Ash. 2012. The logic of pronominal resumption. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Austin, Peter, and Joan Bresnan. 1996. Non-configurationality in Australian Aboriginal languages. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 14(2): 215–268.

Bohnhoff, Lee E. 1986. Yạg Dii (Duru) pronouns. In Pronominal systems, ed. Ursula Wiesemann, 103–129. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Bohnhoff, Lee E. 2010. A Description of Dii: Phonology, Grammar, and Discourse. Dii Literature Team, Ngaoundéré, Cameroon.

Bresnan, Joan. 2001. Lexical-functional syntax. Oxford: Blackwell.

Bresnan, Joan, and Sam A. Mchombo. 1987. Topic, pronoun, and agreement in Chicheŵa. Language 63(4): 741–782.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Clements, George N. 1975. The logophoric pronoun in Ewe: Its role in discourse. Journal of West African Languages 10(2): 141–177.

Culy, Christopher D. 1997. Logophoric pronouns and point of view. Linguistics 35: 845–859.

Dalrymple, Mary. 1993. The syntax of anaphoric binding. Vol. 36 of The Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI) lecture notes. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Dalrymple, Mary. 2001. Lexical functional grammar, syntax and semantics, Vol. 34. New York: Academic Press.

Dimmendaal, Gerrit J. 2001. Logophoric marking and represented speech in African languages as evidential hedging strategies. Australian Journal of Linguistics 21(1): 131–157.

Fitzpatrick, Justin M. 2002. On minimalist approaches to the locality of movement. Linguistic Inquiry 33(3): 443–463.

Givón, Talmy. 2009. Multiple routes to clause union: The diachrony of complex verb phrases. In Syntactic complexity: Diachrony, ontogeny, neuro-cognition, evolution, eds. Talmy Givón and Masayoshi Shibatani. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Haiman, John, and Pamela Munro. 1983. Introduction. In Switch reference and universal grammar, eds. John Haiman and Pamela Munro. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hellan, Lars. 1988. Anaphora in Norwegian and the theory of grammar. Dordrecht: Foris.

Huang, C.-T. James, and J. Tang. 1991. The local nature of the long-distance reflexive in Chinese. In Long-distance anaphora, eds. Jan Koster and Eric Reuland, 263–282. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hyman, Larry M., and Bernard Comrie. 1981. Logophoric reference in Gokana. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 3: 19–37.

Kiparsky, Paul. 2002. Disjoint reference and the typology of pronouns. In More than words: A Festschrift for Dieter Wunderlich, eds. Ingrid Kaufmann and Barbara Stiebels. Vol. 53 of Studia grammatica, 179–226. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Koopman, Hilda, and Dominique Sportiche. 1989. Pronouns, logical variables, and logophoricity in Abe. Linguistic Inquiry 20(4): 555–588.

Langdon, Margaret, and Pamela Munro. 1979. Subject and (switch-)reference in Yuman. Folia Linguistica 32: 321–344.

Manzini, Maria Rita, and Kenneth Wexler. 1987. Parameters, binding theory, and learnability. Linguistic Inquiry 18(3): 413–444.

Mohanan, K. P. 1981. Grammatical relations and anaphora in Malayalam. Master’s thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Nordlinger, Rachel, and Louisa Sadler. 2004a. Nominal tense in crosslinguistic perspective. Language 80(4): 776–806.

Nordlinger, Rachel, and Louisa Sadler. 2004b. Tense beyond the verb: Encoding clausal tense/aspect/mood on nominal dependents. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22(3): 597–641.

Quer, Josep. 2006. Resumption. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk. Vol. 4, 660–684. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sag, Ivan A. 2010. Feature geometry and predictions of locality. In Features: Perspectives on a key notion in linguistics, eds. Anna Kibort and Greville G. Corbett, 236–271. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2003. Indexicality, logophoricity, and plural pronouns. In Research in Afroasiatic grammar II: Selected papers from the Fifth Conference on Afroasiatic Languages, Paris, 2000, 409–428. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sells, Peter. 1987. Aspects of logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry 18(3): 445–479.

Strahan, Tania. 2009. Outside-in binding of reflexives in Insular Scandinavian. In On-line proceedings of the LFG2009 conference, eds. Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. CSLI publications. http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/LFG/14/.

Strahan, Tania. 2011. Antecedent-based approach to binding in Icelandic and Faroese. In Nordlyd, ed. Tania Strahan. Vol. 37, 151–166. Tromsø: CASTL.

Welmers, William Everett. 1973. African language structures. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Lee Bohnhoff, who has responded generously and in detail to numerous questions during his time in Cameroon (1991, by regular mail) and Wisconsin (by email, in 2011–2014). He has provided corrections to mistakes in transcriptions and indices for the examples taken from Bohnhoff (1986), additional examples from his unpublished notes, and very helpful comments on the patterns discussed here and on previous versions of this paper. I am also grateful for helpful discussion and comments to Doug Arnold, Ash Asudeh, Miriam Butt, James German, Dag Haug, Tracy Holloway King, Jean-Marie Marandin, Rachel Nordlinger, Louisa Sadler, and the audiences at “Ling Lunch” Paris Diderot, June 2011; LFG11, Hong Kong, July 2011; the University of Melbourne, August 2012; the Australian National University, September 2012; and Nanyang Technological University, September 2012. I also gratefully acknowledge the support of a Leverhulme Research Fellowship 2012–13, RF-2012-295.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dalrymple, M. Obligatory nonlocal binding. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 1089–1120 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9282-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9282-z

pronominal forms (Bohnhoff

pronominal forms (Bohnhoff

subjects: indirect order, temporal/locative/conditional adjunct, concessive clause, affirmative purpose clause, causal adjunct introduced by ka or bà, relative clause, desiderative clause (Bohnhoff

subjects: indirect order, temporal/locative/conditional adjunct, concessive clause, affirmative purpose clause, causal adjunct introduced by ka or bà, relative clause, desiderative clause (Bohnhoff

clause; antilogophoric in

clause; antilogophoric in  ::

:: clause; antilogophoric in

clause; antilogophoric in

requirement

requirement

forms, requiring the presence of the

forms, requiring the presence of the