Abstract

In this paper we present a treatment for anaphoric pronouns and reflexives in a Type Logical Grammar. To this end, we introduce structural modalities into the left pronominal rule of the categorial calculus with limited contraction LLC [8]. Following a proposal due to Hepple [6], we also sketch an analysis for the long-distance anaphora seg from Icelandic.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

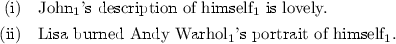

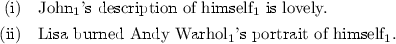

From a generative perspective, the licensing of pronominal expressions such as he, him, himself is determined by the so-called Principles A and B of the Binding Theory [3]. Principle A stipulates that an anaphor (reflexives and reciprocals) must be bound in its governing category (roughly, it must have a c-commanding local antecedent). Principle B stipulates that a pronoun must be free (i.e. not bound) within its governing category; notwithstanding, a pronoun can be bound from outside this syntactic domain. Thus a pronoun, unlike an anaphor, also admits a free reading. Principles A and B jointly imply a strict complementary distribution between pronouns and reflexives in some syntactic domains, as exemplified below:

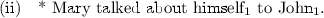

The Binding Theory has been successively revisited to overcome some counterexamples. Complementary distribution is disconfirmed, on the one hand, in adjunct clauses, like in (6) below. On the other hand, languages like Icelandic, Dutch, German and Norwegian each contain an anaphoric form—sig, zich, sich, seg, respectively—that does not meet Principle A, as the former can be bound by a long-distance antecedent (cf. [22]).Footnote 1

Several categorial—combinatory and type-logical—calculi have been proposed to deal with reflexives and anaphoric pronouns. Some of them treat multi- ple-binding into the lexicon (cf. [16, 23]); others use a syntactic approach (cf. [6,7,8]). Working on a Type-Logical Grammar, Jaeger [8] develops the Lambek calculus with Limited Contraction (LLC) to syntactically process personal pronouns in a uniform way; he does not discriminate syntactically (nor semantically) among reflexives, anaphoric pronouns and pronominals. In other words, he does not take Principles A and B of the Binding Theory into account.

Our goal is to give a more accurate treatment of personal pronouns, taking as a starting point the pronominal connective | from Jaeger and the intuition behind its logical rules. Firstly, we modify the right rule of LLC to distinguish on the one hand the free (or pronominal) use from the bound (or anaphoric) use of a personal pronoun. Secondly, by using the (lexical) structural modality  of [18] (and, analogously, for our

of [18] (and, analogously, for our  ), we identify different syntactic domains for binding: we impose structural conditions into the pronominal left rule of LLC by using the corresponding (syntactic) structural modality

), we identify different syntactic domains for binding: we impose structural conditions into the pronominal left rule of LLC by using the corresponding (syntactic) structural modality  (and also

(and also  ). Thus, on the other hand, we also distinguish anaphoric pronouns from reflexive anaphors. As a consequence, although we deal with reflexives, anaphoric pronouns and pronominals, our proposal is not intended to be a uniform approach. For reasons of space, we restrict ourselves to cases where the binder is a nominal phrase and the bindee (a pronoun or a reflexive) carries 3sg features.Footnote 2 Since our proposal is inspired by Jaeger’s calculus, we also do not deal with cases in which the bindee precedes its binder.Footnote 3

). Thus, on the other hand, we also distinguish anaphoric pronouns from reflexive anaphors. As a consequence, although we deal with reflexives, anaphoric pronouns and pronominals, our proposal is not intended to be a uniform approach. For reasons of space, we restrict ourselves to cases where the binder is a nominal phrase and the bindee (a pronoun or a reflexive) carries 3sg features.Footnote 2 Since our proposal is inspired by Jaeger’s calculus, we also do not deal with cases in which the bindee precedes its binder.Footnote 3

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Sect. 2, we present Jaeger’s calculus LLC (in a sequent format) and we briefly discuss some questions related to the problem of overgeneration. In Sect. 3 we change the right pronominal rule of LLC to distinguish between a reflexive and a pronominal type-constructor. In Sect. 4, firstly we present our treatment for subject-oriented anaphors in several syntactic domains and secondly, we deal with object-oriented anaphors in double-object constructions and prepositional complements. Finally, we sketch an analysis for long-distance anaphors from Icelandic. Section 5 concludes the paper. In the Appendix we sketch the principal cut for our new pronominal rules.

2 LLC Calculus

LLC is a conservative extension of the Lambek L calculus (without empty antecedents) [9]. Like L, LLC is free of structural rules. Jaeger’s calculus treats resource multiplication syntactically. LLC extends the sequent calculus L by adding the anaphoric type-constructor |. The rules of the latter encode a restricted version of the structural rule of Contraction, thus allowing for multiple-binding (see Fig. 1). Despite incorporating this structural rule, LLC, as well as Lambek system, enjoys Cut elimination, decidability and the subformula property. Indeed, as the reader can check, all the formulas that occur in the premises of the two new rules for the anaphoric type-constructor are subformulas of the formulas that occur in their conclusion.

Note that when A is a basic type, the left premise of |L is an instance of the identity axiom; thus the rule can be simplified, as shown in Fig. 2.Footnote 4

Anaphoric expressions are then assigned a type B|A: it works as a type B in the presence of an antecedent of type A. The |L rule expresses the fact that for an anaphoric expression to be bound it needs an antecedent in the same premise, that is, in some local syntactic domain. Besides imposing an antecedent condition, this rule incorporates a restricted version of the structural rule of (long-distance) Contraction, in that the antecedent A for the anaphoric type B|A occurs in both premises of this rule.

Since personal pronouns take their reference from a nominal antecedent, they are assigned the syntactic anaphoric category n|n.Footnote 5 In semantic terms, a pronoun denotes the identity function \(\lambda x.x\) over individuals; the reference of a pronoun is identical with the reference of its antecedent.Footnote 6

Since a pronominal type n|n can be constructed by using the |R and |L rules, and since anaphoric and pronominal pronouns are assigned the same syntactic type (and the same semantic category), the system can accurately recognize the free and the bound readings for a pronominal. Thus, for example, the system recognizes the double reading for he in (5), and so may assign it the saturated type s or the unsaturated (or functional) type s|n. The latter expresses the fact that a free pronoun occurs in the clause. In addition, the system can also derive the co-occurrence of bound pronouns and reflexives in syntactic domains in which complementary distribution fails, as exemplified in (6) above (see Fig. 3). It can also recognize the ungrammaticality of (8b) below, since the antecedent condition on |L is not fulfilled. Nevertheless, LLC also allows for the ungrammatical anaphoric readings in the following examples.Footnote 7

Since we are looking for a more accurate treatment for the distribution of pronominal and anaphoric pronouns, we shall begin by distinguishing between an anaphoric connective for reflexives and a (possibly) non-anaphoric connective for personal pronouns like he and him. Later on, we shall draw a distinction between reflexives and bound pronouns.

3 Bound and Free Pronouns: Splitting the Pronominal Connective

For non-reflexive pronouns, we adopt Jaeger’s left rule and the following left and right rules, which split the |R rule of LLC. It is important to emphasize that these two new rules, like those of LLC, satisfy the subformula property: all the formulas that occurs in the premises of \(\Vert \)L and \(\Vert \)R are subformulas of the formulas that occurs in their conclusion. Given that the proof of Cut elimination for these rules requires using a limited version of the Expansion rule (see Appendix), we call our modified version of Jaeger’s system LLBE: Lambek calculus with Bracketed Expansion (Fig. 4).

As can be noted, we split (an extremely simplified version of) the |R rule of LLC to obtain a second left rule.Footnote 8 Hence, a pronominal type-constructor will have two left rules: |L and \(\Vert \)L.Footnote 9 By breaking the |R rule of LLC we can more clearly show that free and bound are labels that result from the procedures by which we use a pronoun: we apply the rule of use |L to get a bound (or anaphoric) use of a pronoun, while in applying \(\Vert \)L we use a pronoun freely.Footnote 10

The \(\Vert \)R rule compiles a restricted form of the structural rule of Expansion, as it introduces a formula that is a sub-formula of the pronominal type \(C\Vert A\). Given that we do not assume logical rules for the brackets  , they can only be introduced (deleted) through the use of the \(\Vert \)R (\(\Vert \)L) rule. Consequently, like in Jaeger’s proposal, the rule of proof for a free pronoun goes hand in hand with its free use in LLBE. However, unlike the |R rule of LLC, the \(\Vert \)R rule of LLBE does not simultaneously construct a pronominal type to the left and to the right sides of a sequent.

, they can only be introduced (deleted) through the use of the \(\Vert \)R (\(\Vert \)L) rule. Consequently, like in Jaeger’s proposal, the rule of proof for a free pronoun goes hand in hand with its free use in LLBE. However, unlike the |R rule of LLC, the \(\Vert \)R rule of LLBE does not simultaneously construct a pronominal type to the left and to the right sides of a sequent.

In addition, since LLBE contains two left pronominal rules (i.e. |L and \(\Vert \)L), we are able to characterize two anaphoric type-constructors: a reflexive type-constructor, which uses only the |L rule, and a pronominal type, which uses |L, \(\Vert \)R and also \(\Vert \)L.Footnote 11 By assigning different syntactic types for reflexives and pronouns—n|n and \(n\Vert n\), respectively—, and given that the |R rule of LLC for the case \(n=1\) may be derived by using \(\Vert \)L and \(\Vert \)R of LLBE, the latter system, like the former one, adequately recognizes grammatical sentences like those in (12–16a), whilst blocking the ungrammatical sentence in (16b) below (Fig. 5).

Nevertheless, since |L is adopted for the pronominal type \(n\Vert n\) and also for the anaphoric type n|n, LLBE is not yet capable of separating bound (object) pronouns from reflexives.Footnote 12

4 Reflexives and Bound Pronouns: Imposing Structure Through Bracket Modalities

4.1 Subject-Oriented Reflexives and Bound Pronouns

There are several syntactic domains where a reflexive can occur: in nominal object complements, prepositional object complements, adjunct clauses, and even in an embedded position within nominal phrases (the so-called NP anaphora). In some of them, complementary distribution is fully verified: when the reflexive and its antecedent are co-arguments of the same function, a bound pronoun is ruled out.

Propositional Complements. Complementary distribution is also verified in the opposite direction in (some) clauses selected by propositional verbs like say and believe. As is widely known, reflexives are ruled out and bound pronouns are licensed in (finite) propositional complements of both these verbs, as exemplified below:

Anaphors within propositional complements have already been adequately analyzed in Categorial Grammar (cf. [6, 15, 23], a. o.). The correct binding relation in these complements is ensured by using a normal (or semantic) S4 modality \(\square \) [13]. In these categorial proposals, reflexives and pronouns are assigned different pronominal types. The following modalized lexical entries capture the above-mentioned facts:

- him/he:

-

: \(\square (\square n\Vert n)\)

- himself:

-

: \(\square (n|n)\)

- say/believe:

-

: \(\square ((n\backslash s) / \square s)\)

- walk:

-

: \(\square (n\backslash s)\)

- hate:

-

: \(\square ((n\backslash s)/n)\)

Nevertheless, authors have sometimes glossed over the fact that a reflexive may occur within a propositional complement if it occupies an embedded position:

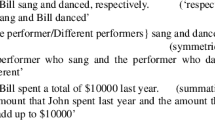

Similarly, it has not always been noted that believe licenses the occurrence of a reflexive in the subject position when the complement verb is in a non-finite form.Footnote 13 This last fact is a specific case of a more general situation: in complements of Exceptional Case Marked (ECM) verbs, such as believe or expect, a reflexive is allowed, while a bound pronoun is ruled out in the subject (and also the object) argument slot. Thus, in ECM constructions, the claimed complementary distribution is verified, as in other verb complements. Nevertheless, complementary distribution in ECM constructions is, in some sense, unexpected, since the reflexive in the subject position of non-finite complements is not a co-argument of the binder.

From this evidence, it seems important to differentiate the lexical entry for a propositional believe from the ECM believe, despite the fact that both verbs select a sentential (finite or non-finite) complement. Following [12, 14, 18], we shall use the structural modality  to mark the (syntactic) argument positions of a verb; though we shall use it to mark not only the subject position, but also the object complement position. In order to distinguish the propositional verb believe/say from non-propositional verbs, we shall set a different bracket modality

to mark the (syntactic) argument positions of a verb; though we shall use it to mark not only the subject position, but also the object complement position. In order to distinguish the propositional verb believe/say from non-propositional verbs, we shall set a different bracket modality  aside for the former.

aside for the former.

A sample of a bracketed lexicon is given below:

- walk:

-

: \(\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s\)

- like/hate/kiss:

-

: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/\left\langle n\right\rangle \)

- say/believe:

-

: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s) / \left\lceil s\right\rfloor \)

- john/mary:

-

: n

- him:

-

: \(n\Vert n\)

- himself:

-

: n|n

The right rules for brackets  and

and  are given below. The rules for Lambek’s slashes are applied to structured sequences \(\left[ X\right] \) and \(\left\{ X\right\} \) of types.Footnote 14 The structures

are given below. The rules for Lambek’s slashes are applied to structured sequences \(\left[ X\right] \) and \(\left\{ X\right\} \) of types.Footnote 14 The structures  and

and  are then spread over the sequents when functional types A/B and \(B\backslash A\) are built out of [B] and \(\left\{ B\right\} \), respectively. Hence, while the structural modality

are then spread over the sequents when functional types A/B and \(B\backslash A\) are built out of [B] and \(\left\{ B\right\} \), respectively. Hence, while the structural modality  is a lexical mark, the insertion of the modalities

is a lexical mark, the insertion of the modalities  and

and  , and thus the delimitation of syntactic domains, is a consequence of syntactic operations (Figs. 6 and 7).

, and thus the delimitation of syntactic domains, is a consequence of syntactic operations (Figs. 6 and 7).

We propose, consequently, bracketed versions for the |L\(_{a}\) and \(\Vert \)L\(_{a}\) rules, with the following side conditions: \(X_{1}\ne \epsilon \) or \(X_{2}\ne \epsilon \) in [\(\Vert \)]L\(_{a}\); \(Z_{3}\ne \epsilon \) in \(\left\{ |\right\} \)L\(_{a}\).Footnote 15

The rule [|]L\(_{a}\) in Fig. 8 preserves the prominence condition on the binder for reflexives: given that the reflexive within an argument domain  takes [A] as its binder, the binder itself is not part of the subject (i.e. higher) argument. Conversely, the side conditions on the sequences \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) in \([\Vert ]\)L\(_{a}\) impede binding of a pronoun in an argument position if the binder is not part of the higher subject argument.

takes [A] as its binder, the binder itself is not part of the subject (i.e. higher) argument. Conversely, the side conditions on the sequences \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) in \([\Vert ]\)L\(_{a}\) impede binding of a pronoun in an argument position if the binder is not part of the higher subject argument.

Note that there is no condition on the sequences \(X_{1}\) and \(X_{2}\) in the rule for pronouns \(\left\{ \Vert \right\} \)L\(_{a}\) in Fig. 9. Thus, a pronoun within a propositional complement can be bound by a matrix subject (see Fig. 10). The side condition on the reflexive \(\left\{ |\right\} \)L\(_{a}\) rule ensures that the reflexive stands in an embedded position within the propositional complement clause (contrast Figs. 11 and 12).

Nominal Complements. In nominal complements complementary distribution is fully verified: where the anaphora and its antecedent are co-arguments of the same function, a bound pronoun is ruled out. Nevertheless, a pronoun in the object complement position can still be bound provided that the binder itself is an argument of another functional type, as exemplified below:

From the following (bracketed) lexicon we may obtain the correct binding relations for reflexives and pronouns within the (direct) object argument position, as exemplified in (23–24) above and in (25–28) below (Fig. 13):

- see/like:

-

: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/\left\langle n\right\rangle \)

- john/mary:

-

: n

- father/picture:

-

: cn

- the/a:

-

: n/cn

- of:

-

: \((n\backslash n)/n\)

- ’s:

-

: \(n\backslash (n/cn)\)

Prepositional Phrases. In general terms, scholars agree that prepositional phrases (PPs) selected by a verb can only contain a reflexive but not a bound pronoun, while prepositional phrases operating as adjuncts allow both a reflexive and a bound pronoun (cf. [4]).

Since our proposal strongly depends on the syntactic types assigned to the lexical items into the lexicon, the correctness of our proposal for anaphoric items within prepositional phrases mainly rests on the type assigned to the different classes of verbs.

Unfortunately, the distinction between complement prepositional phrases and adjunct phrases is not so pure in some cases. As claimed in [10], locative PPs, including those selected by a verb, must be distinguished from other PPs. Those verbs that select a PP bearing a locative role like put and sit, allow several locative prepositions, such as in, on, near, into, next, in front of. In this sense, locative PPs resemble adjunct PPs. By contrast verbs like relies, despite selecting a PP as complement, also select some specific preposition. The PP headed by on/upon in relies on/upon does not bear a locative role. Given this, it seems clear that we need to set a distinction between the PP selected by verbs like put and the PP selected by verbs like relies. In other terms, we need to set a bipartition into the set of PP complements: locative PPs and non-locative PPs. By using the bracket modality  we mark the non-locative PP complement position into the lexical entry of the corresponding verbs and, taking into consideration the similarity between adjunct PPs and locative PP complements, we leave the PP position for the locative complement unmarked.Footnote 16

we mark the non-locative PP complement position into the lexical entry of the corresponding verbs and, taking into consideration the similarity between adjunct PPs and locative PP complements, we leave the PP position for the locative complement unmarked.Footnote 16

Given that reflexives and anaphoric pronouns can occur within an unmarked position, we assume the following rules to process them (Fig. 14):

Thus, assuming the following lexicon, we obtain the correct binding relation in different prepositional phrases, as exemplified in (29–32):

- put/see:

-

: \(((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/pp)/\left\langle n\right\rangle \)

- glance:

-

: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/ pp\)

- rely:

-

: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/\left\langle pp\right\rangle \)

- on/upon/behind/next:

-

: pp/n

4.2 Object-Oriented Reflexives and Bound Pronouns

Nominal Complements. Verbs like show, give, send, promise, introduce may select two nominal phrases as complements, and thus give rise to double-object constructions. These structures allow then for another pattern of reflexivization: reflexives bound by a nominal within a verb complement position. In other terms, besides subject-oriented reflexives, double-object constructions also allow for object-oriented ones. Double-object constructions alternate with oblique dative structures:

Although the two structures display a different linear order, both reveal the same behavior when licensing anaphors. They show an asymmetry with respect to the licensing of object-oriented reflexives. As shown in the examples below, the correct binding relation for object-oriented reflexives in both structures depends on an ordering of the complements.

Thus, these structures indicate that a hierarchical order between the two objects has to be imposed. To deal with double-object constructions we extend the calculus by adding a new product type-constructor.Footnote 17 We also present a different inference rule for object-oriented reflexives, where \(Z_{1}\) does not contain a subtype s (Figs. 15 and 17).Footnote 18

The correct binding relation is ensured by the following lexical assignment:

- show/give/present/send:

-

:

- show/give/present/send:

-

:

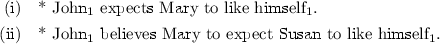

Prepositional Phrases: The About-Phrase. Verbs selecting two prepositional phrases also challenge several binding theories. In this case, there is also no complete agreement among scholars with respect to their syntactic status.Footnote 19 As is known, two prepositional complements may appear in either order:

Despite the free word-order, the occurrence of a reflexive within a prepositional phrase, such as in double-object structures, indicates that a structural ordering between the about-phrase and the to-phrase has to be imposed.

In a categorial framework, it is the functional type assigned to a verb like talk which has to express the different syntactic relation that these two PPs maintain with the verb. In [16], for example, the type assigned to talk is \(((n\backslash s)/pp)/pp\), while in [19] it is the type \((n\backslash s)/(pp_{to} \otimes pp_{about})\), where \(\otimes \) is the nondeterministic continuous product of the Displacement Calculus D. Thus, this last type captures the alternative surface word-order. This notwithstanding, by using either the former or the latter type, prepositional phrases both get the same syntactic non-hierarchical status of verb complements.Footnote 20

Hence, the different hierarchical relation the PPs complements maintain with the verb seems to call for a new type-constructor that is analogous to that we have used to deal with double-object constructions, but which encodes commutativity as well (Figs. 18, 19 and 20).

With this type-constructor at hand, we then propose the following lexical assignment:

- talk:

-

:

4.3 Long-Distance Anaphors

Anaphors in Icelandic are necessarily subject-oriented and do not respect Principle A for anaphors, as they can be bound by a long-distance antecedent, provided that the anaphora stands in a subjunctive clause. In this sense, long-distance anaphors resemble anaphoric pronouns in propositional (finite) complements from English. In addition, the subjunctive mood in Icelandic may be propagated down through embedded complements (this is the so-called domino effect). Given that bracket modalities have been applied in Type-Logical Grammar to delimit syntactic domains, we suggest using the bracket  to simulate the domino effect of the subjunctive mood generated by some verbs (e.g. segir ‘say’ vs. víta ‘know’) and the bracket

to simulate the domino effect of the subjunctive mood generated by some verbs (e.g. segir ‘say’ vs. víta ‘know’) and the bracket  to ensure binding only by the subject (that is, the subject condition; cf. [18]). Since the licensing of a long-distance anaphor in this language also depends on the case properties of the binder and bindee, we merely sketch an analysis here. The left rule for long distance anaphors is given in Fig. 21.

to ensure binding only by the subject (that is, the subject condition; cf. [18]). Since the licensing of a long-distance anaphor in this language also depends on the case properties of the binder and bindee, we merely sketch an analysis here. The left rule for long distance anaphors is given in Fig. 21.

- segir:

-

‘say’: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/\left\lceil s\right\rfloor \)

- víta:

-

‘know’: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/s\)

- elskar:

-

‘love’: \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/n\)

5 Conclusions

In this paper we have proposed different rules to deal with anaphoric and pronominal pronouns occurring in several syntactic domains. Although both the type assignment for pronouns and our initial idea for the pronominal rules come from Jäeger [8], we have proposed a different type assignment for reflexives and pronominal pronouns and we have modified the rules of LLC. The inspiration for lexical entries encoding marked argument positions comes from [18]. By adopting bracket modalities we have identified different syntactic domains; in light of the latter, we have encoded binding restrictions into the left anaphoric rule of LLBE. The right pronominal rule of LLBE, in turn, evidences that despite the fact that an antecedent A could occur in the local syntactic domain  , a free pronoun is derived by assuming an antecedent in a non-local domain

, a free pronoun is derived by assuming an antecedent in a non-local domain  . The rules of LLBE reveal then that free and anaphoric pronouns on the one hand, and bound pronouns on the other, are generally processed in different steps in a proof: if \(X_{1}=X_{2}=\epsilon \) and so the antecedent A is left-peripheral, free pronouns and reflexives, but not bound pronouns, can be inserted into a derivation. Our proposal preserves the prominence condition on the binder for reflexives: the binder may not be an argument lower in the hierarchy and neither may it be part of an argument higher in the hierarchy. In addition, we have incorporated the previous modal categorial analysis for say in terms of structural modalities, in accordance with our overall proposal. Further, we have suggested how this proposal can be used to deal with long-distance anaphors in Icelandic. Our rule for object-oriented reflexives could also be used to deal with non-subject- and non-object-oriented reflexives, such as anaphors in possessive complements.

. The rules of LLBE reveal then that free and anaphoric pronouns on the one hand, and bound pronouns on the other, are generally processed in different steps in a proof: if \(X_{1}=X_{2}=\epsilon \) and so the antecedent A is left-peripheral, free pronouns and reflexives, but not bound pronouns, can be inserted into a derivation. Our proposal preserves the prominence condition on the binder for reflexives: the binder may not be an argument lower in the hierarchy and neither may it be part of an argument higher in the hierarchy. In addition, we have incorporated the previous modal categorial analysis for say in terms of structural modalities, in accordance with our overall proposal. Further, we have suggested how this proposal can be used to deal with long-distance anaphors in Icelandic. Our rule for object-oriented reflexives could also be used to deal with non-subject- and non-object-oriented reflexives, such as anaphors in possessive complements.

In future work, we propose to investigate how to impose structural conditions upon the sequences of the left rules for the customized slash type-constructors in order to reduce the number of pronominal rules and thus to deal with subject and object anaphoric pronouns in a more uniform way. We also plan to explore how to deal with ECM constructions.

Notes

- 1.

Although these languages contain this kind of simple (also weak) reflexive form, their syntactic behavior is not the same in all of them (cf. for example, [5]).

- 2.

Hence, we restrict ourselves to what some theories call anaphoric coreference, not binding (cf. [2, 21]). Though it is generally accepted that reflexives and reciprocals behave in the same way with respect to binding conditions, their semantic value diverges. For this reason, we also do not deal with reciprocal anaphors.

- 3.

However, a version of Jaeger’s rules that also allows cases of cataphora is presented in [17].

- 4.

Jaeger is not only concerned with anaphoric pronouns but also with other anaphoric phenomena, such as ellipsis of VP.

- 5.

As usual, we use n for proper names, s for sentences, cn for common nouns and pp for prepositional phrases.

- 6.

- 7.

Everaert [4] uses these sentences to evaluate the scope and limits of several generative models for binding.

- 8.

Strictly speaking, we split the |R rule of LLC for the case where \(n=1\) and X is the empty sequence \(\epsilon \). As we shall show in the Appendix, the proof of principal Cut for the new rules requires using bracketed versions of the structural rules of Permutation and Expansion. In order to avoid a proof of a pronominal type \(C\Vert A\) for any type C, the antecedent type A of the rule \(\Vert \)R has to be left-peripheral.

- 9.

From Sect. 4, the |L rule (for non-reflexive pronouns) will be renamed \(\Vert \)L\(_{a}\), and \(\Vert \)L will have to be read as \(\Vert \)L\(_{p}\). Though we shall retain |L for reflexives only, we will rename it |L\(_{a}\) for the sake of uniformity.

- 10.

As we shall see later, the formula B in the \(\Vert \)L rule will have a bracketed structure [B] in most cases.

- 11.

A Type-Logical sequent calculus generally contains one left and one right rules for each type-constructor. Since in our proposal the reflexive type-constructor uses only a left rule, our approach is non-standard.

- 12.

In order to distinguish subject and object pronouns, we could assign the lifted type \((s\Vert n)/(n\backslash s)\) to the former (cf. [17]). Although at first glance it would seem that a lifted type—\((s/n)\backslash (s\Vert n)\)—is also adequate to categorize an object pronoun like him, it is not clear how we could deal with Exceptional Case Marked (ECM) constructions, in which the semantic argument of the embedded infinitive clause surfaces with accusative case. Indeed, if him were assigned \((s/n)\backslash (s\Vert n)\) because of its surface form, it would combine with a verb phrase to the left, like a real object complement does. But if this were the case, the subject slot of the embedded complement clause would not be saturated and then, the sentential argument of the ECM verb would become unsaturated as well.

- 13.

In passing, we point out that, unlike English, literary Spanish and Italian allow a nominative free or bound pronoun in non-finite complements of propositional verbs [11].

- 14.

Generally, \(\varDelta [\varGamma ]\) indicates a configuration \(\varDelta \) containing a distinguished configuration \(\varGamma \) of types. In our rules, X[Z] would indicate a sequence X with a distinguished structured sequence [Z] of types, and analogously for \(\left\{ Z\right\} \).

- 15.

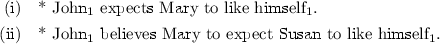

As an anonymous reviewer pointed out, if the type \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/s\) were assigned to ECM verbs to differentiate them from propositional verbs, it would allow for ungrammatical sentences like (i–ii) below. To block binding of a reflexive in an object position by a non-local antecedent it seems we would have to impose some condition on the sequence \(Z_{1}\) in [|]L\(_{a}\). We plan to address the challenge posed by ECM constructions in future investigations.

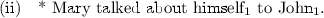

In addition, the side conditions on the [\(\Vert \)]L\(_{a}\) rule inadequately license pronouns to be bound by an antecedent within a conjunctive nominal phrase, as exemplified below. Indeed, Mary is taken as an argument of the functional type commonly assigned to and:

It appears that the unbracketed type assigned to the conjunction and has to be differentiated from the (bracketed) functional types assigned, for example, to of—\((n\backslash n)/\left\langle n \right\rangle \) and ’s—\(\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash (n/cn)\). A distinction between a collective and a distributive type for and also seems to be relevant: roughly, \(X\backslash X/X\) and \(\left\langle X\right\rangle \backslash X/\left\langle X\right\rangle \), for example. For reasons of space, and since judgments seem to vary among speakers and sentences, we defer this problem to future research.

- 16.

Alternatively, Reinhart and Reuland [22] consider that relies on forms a complex (semantic and syntactic) unit selecting a nominal complement, whilst put selects a prepositional complement. In view of this fact, we would assign the type \((\left\langle n\right\rangle \backslash s)/\left\langle n\right\rangle \) to relies on/upon.

- 17.

Note that the product

is not a discontinuous (or wrapping) type-constructor, unlike that of [1] or [19]. Since

is not a discontinuous (or wrapping) type-constructor, unlike that of [1] or [19]. Since  is non-commutative, we would not be able to derive cases of “heavy” NP, as exemplified below. Nevertheless, in the following section we shall adopt a commutative product-type for the treatment of prepositional phrases.

is non-commutative, we would not be able to derive cases of “heavy” NP, as exemplified below. Nevertheless, in the following section we shall adopt a commutative product-type for the treatment of prepositional phrases.

To deal with double-object structures, Hepple [6] extends the L calculus by adding a new slash type-constructor \(\oint \) and a modality \(\triangleright \). Since the slash type-constructor lacks introduction rules, it may encode the hierarchical ordering of the nominal complements; the modality allows the nominal complements to be reordered to obtain the correct surface word-order.

- 18.

We note that a slightly modified version of the rule in Fig. 16 may also be used for anaphors in a complement of possessives, which are not either subject nor object-oriented. Once again, it appears that a distinction between the functional type assigned to of or ’s and and has to be made to prevent He and himself from assigning the type n.

It seems that it could be possible to also encode a hierarchical ordering into the rules for the Lambek slash type-constructors. In this case, it would be possible to deal with subject- and object-oriented anaphors in a uniform way.

- 19.

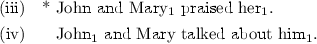

In some generative theories, the about-phrase is evaluated as an adjunct phrase and thus is separated from the to-phrase or with-phrase complement (cf. [22]). This would explain the ungrammaticality of (40), but not the ungrammaticality of (i) below.

In other theories, the about-phrase, as well as the to-phrase, is considered a verb complement; the difference between these PPs is made by assuming an ordering with respect to their relative obliqueness: the about-phrase is more oblique than the to-phrase (cf. [20]). Since the anaphor has to be bound by a less oblique co-argument, the relationship of relative obliqueness would account for (i) above, but not for (ii) below, where the linear word-order seems to be also relevant.

In addition, [3] suggests an approach in which the verb talk (and also speak) and the preposition to are reanalyzed as one verb taking a nominal object (and a prepositional complement) (cf. also [23]). Thus, talk would be analogous to (one of the forms of) tell. To formalize this proposal, besides encoding free linear word-order and relative obliqueness, the syntactic functional type assigned to the talk to-phrase would have to encode discontinuity as well.

- 20.

Since the calculus D also contains a nondeterministic discontinuous product \(\odot \), the type \((n\backslash s)/(pp\odot pp)\) would take the structural ordering into account if the premisses of the right rule were bracketed sequences.

References

Bach, E.: Control in montague grammar. Linguist. Inq. 10(4), 515–531 (1979)

Büring, D.: Pronouns. In: Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning, vol. 2, pp. 971–996 (2011)

Chomsky, N.: Lectures on Government and Binding. Kluwer, Dordrecht (1981)

Everaert, M.: Binding theories: a comparison of grammatical models. In: van Oostendorp, M., Anagnostopoulou, E. (eds.) Progress in Grammar. Articles at the 20th Anniversary of the Comparison of Grammatical Models Group in Tilburg. Meertens Institute, Electronic Publications in Linguistics, Amsterdam (2000)

Hendriks, P., Hoeks, J., Spenader, J.: Reflexive choice in Dutch and German. J. Comp. Ger. Linguist. 17(3), 229–252 (2015)

Hepple, M.: Command and domain constraints in a categorial theory of binding. In: Proceedings of the Eight Amsterdam Colloquium, pp. 253–270 (1992)

Jacobson, P.: Towards a variable-free semantics. Linguist. Philos. 22(2), 117–185 (1999)

Jäeger, G.: Anaphora and Type Logical Grammar. Trends in Logic - Studia Logica Library, vol. 24. Springer, Dordrecht (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3905-0

Lambek, J.: The mathematics of sentence structure. Am. Math. Mon. 65(3), 154–170 (1958)

Marantz, A.P.: On the Nature of Grammatical Relations. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs Ten. The MIT Press, Cambridge (1984)

Mensching, G.: Infinitive constructions with specified subjects: a syntactic analysis of the romance languages (2000)

Moortgat, M.: Multimodal linguistic inference. J. Logic Lang. Inform. 5(3–4), 349–385 (1996)

Morrill, G.: Intensionality and boundedness. Linguist. Philos. 13(6), 699–726 (1990)

Morrill, G.: Categorial formalisation of relativisation: pied piping, islands, and extraction sites. Technical report, Departament de Llenguatges i Sistemes Informàtics, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (1992)

Morrill, G.: Type Logical Grammar. Categorial Logic of Signs. Springer, Dordrecht (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-1042-6

Morrill, G., Valentín, O.: On anaphora and the binding principles in categorial grammar. In: Dawar, A., de Queiroz, R. (eds.) WoLLIC 2010. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 6188, pp. 176–190. Springer, Heidelberg (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13824-9_5

Morrill, G., Valentín, O.: Semantically inactive multiplicatives and words as types. In: Asher, N., Soloviev, S. (eds.) LACL 2014. LNCS, vol. 8535, pp. 149–162. Springer, Heidelberg (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-43742-1_2

Morrill, G., Valentín, O.: Computational coverage of TLG: displacement. In: Proceedings of Empirical Advances in Categorial Grammar, pp. 132–161 (2015)

Morrill, G., Valentín, O., Fadda, M.: The displacement calculus. J. Logic Lang. Inform. 20(1), 1–48 (2011)

Pollard, C., Sag, I.A.: Anaphors in English and the scope of binding theory. Linguist. Inq. 23(2), 261–303 (1992)

Reinhart, T.: Coreference and bound anaphora: a restatement of the anaphora questions. Linguist. Philos. 6(1), 47–88 (1983)

Reinhart, T., Reuland, E.: Reflexivity. Linguist. Inq. 24(4), 657–720 (1993)

Szabolcsi, A.: Bound variables in syntax (are there any?). In: Bartsch, R., van Benthem, J., van Emde Boas, P. (eds.) Semantics and Contextual Expressions, pp. 295–318. Foris, Dordrecht (1989)

Acknowledgment

The author was supported by a doctoral scholarship granted by FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, process number 2013/08115-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

The proof for the Cut elimination theorem requires the use of the following bracketed versions of the structural rules of Permutation and Expansion (Fig. 22). In order to prove Cut Elimination for LLBE we have to consider two more cases for principal Cut: the left premise of Cut is the conclusion of \(\Vert \)L\(_{a}\) or that of \(\Vert \)L\(_{p}\) and the right premise is the conclusion of \(\Vert \)R. These two configurations are given schematically in Figs. 23 and 24. In both cases, the principal Cut is replaced by a Cut of lower degree. Since no rule introduces a formula  into the right side of a sequent (i.e. there are only antecedent occurrences of the formula

into the right side of a sequent (i.e. there are only antecedent occurrences of the formula  ), the Cut formula could not have been derived by applying either of the bracketed structural rules.

), the Cut formula could not have been derived by applying either of the bracketed structural rules.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany

About this paper

Cite this paper

Corbalán, M.I. (2018). Binding Domains: Anaphoric and Pronominal Pronouns in Categorial Grammar. In: Foret, A., Muskens, R., Pogodalla, S. (eds) Formal Grammar . FG 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10686. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56343-4_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56343-4_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-56342-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-56343-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)

and structured

and structured  sequents

sequents

and structured

and structured  sequents

sequents

domain

domain

domain

domain

asymmetrical product

asymmetrical product

is not a discontinuous (or wrapping) type-constructor, unlike that of [

is not a discontinuous (or wrapping) type-constructor, unlike that of [ is non-commutative, we would not be able to derive cases of “heavy” NP, as exemplified below. Nevertheless, in the following section we shall adopt a commutative product-type for the treatment of prepositional phrases.

is non-commutative, we would not be able to derive cases of “heavy” NP, as exemplified below. Nevertheless, in the following section we shall adopt a commutative product-type for the treatment of prepositional phrases.