Abstract

Past research on gratitude assumes that norms of reciprocity are incompatible with personal relationships as they are based on the rigid normative expectations characteristic of market-based exchange. Challenging this assumption, the present investigation demonstrates the importance of recognizing that norms of reciprocity take a less rigid and more tacit form in the case of personal relationships. Using a vignette-based experiment, Study 1 (N = 200) demonstrated that when expectations to reciprocate are framed in ways that reflect their normative character rather than are portrayed as based on self-interested individual expectations, this is associated with greater likelihood of helping, enhanced gratitude, and more positive personality impressions. In an online game, Study 2 (N = 108) showed that players reciprocate less money to their exchange partner in the presence as compared with the absence of self-interested individual expectations for return. Assessing real life helping among friends, Study 3 (N = 128) revealed that indebtedness is predictive of helping and that indebtedness and gratitude promote relationship closeness in contrasting ways.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Both gratitude and reciprocity are involved in the giving of benefits. Gratitude is a feeling that motivates giving benefits out of a benevolent desire to be helpful (Tsang, 2007). In contrast, reciprocity is a normative expectation, giving rise to feelings of indebtedness, that involves an obligation to return benefits that one has received (Schwartz, 1967; Visser, 2008). The norm of reciprocity applies in cases in which a benefactor intentionally gives a benefit to a beneficiary. In turn, indebtedness is the feeling associated with the norm of reciprocity that involves the recipient of an intentionally given benefit experiencing a felt onus to return.

Theorists within positive psychology assume that only gratitude and not the norm of reciprocity and its associated feeling of indebtedness play a central role in the type of helping that occurs in personal relationshipsFootnote 1 (e.g. Algoe 2012; Fredrickson, 2004). This view is based on the claim that the norm of reciprocity assumes the same rigid market-based form in all contexts, with this form incompatible with the closeness of personal relationships. Challenging this assumption, the present investigation highlights the importance of recognizing that the norm of reciprocity assumes a qualitatively distinct form in everyday social support contexts,Footnote 2 as compared with in market-based transactions. In the case of personal relationships, the norm of reciprocity is based on social expectations that are tacit rather than explicit in nature. These expectations entail considerable individual discretion in the type of reciprocation considered acceptable, rather than requiring that benefits returned be equivalent to benefits received. By taking into account these distinctive features associated with the norm of reciprocity in everyday social support contexts, the present investigation provides evidence that adherence to the norm of reciprocity explains helping previously attributed to gratitude. Our investigation further demonstrates that feelings of indebtedness and not only of gratitude contribute to the closeness of personal relationships.

Evidence for roles of gratitude and reciprocity in social support

Research provides evidence to suggest that gratitude explains helping in ways that cannot be explained by the norm of reciprocity and its associated emotion of indebtedness. In an early lab-based behavioral study, Goei & Boster (2005) (see also Goei et al., 2003) demonstrated that increase in the cost of a benefit received from a confederate enhanced gratitude and likelihood of later helping this confederate, whereas cost did not enhance obligation to help, their index of reciprocity. However, the authors acknowledged that this latter unexpected finding may have resulted from a “failed obligation induction” (Goei & Boster, 2005, p. 291).

In an influential lab-based experiment, Bartlett & DeSteno (2006) showed that participants who received help from a confederate expressed more gratitude and were more likely later to spend time giving costly help to this confederate as well as to aid a third party than were participants who had not received this help. Although Bartlett and DeSteno did not include a measure of indebtedness, they interpreted their findings as supporting the claim that gratitude, and not reciprocity, motivates costly helping because the cost of the help they assessed went beyond that which they assumed was required for reciprocation. In making this argument, the authors applied the expectation associated with market-based forms of reciprocity that returns must be equivalent to benefits received and that individuals are not expected to help their benefactor any more than that which is necessary to absolve their debt. Bartlett and DeSteno also argued that third-party help could not be explained by reciprocity as, in their view, a benefactor is not indebted to individuals from whom they did not receive benefits. This latter claim, however, does not take into account third-party return in generalized reciprocity (Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Molm, 2010).

In another lab-based behavioral experiment, Tsang (2007) showed that participants who received valuable raffle tickets as a favor from a confederate later donated more raffle tickets to the confederate than did participants who had received the raffle tickets by chance. Regression analysis revealed that both gratitude and indebtedness were strong predictors of the number of raffle tickets distributed, although the regression structure coefficients indicated that gratitude was more strongly related to the tickets distributed than was indebtedness. Also, gratitude decreased more than indebtedness after reciprocation of the raffle tickets. Tsang interpreted her findings as compatible with helping being motivated more by gratitude than by indebtedness. However, she also acknowledged that the differential effect of reciprocation on the two emotions was inconclusive in that it may have resulted from “statistical phenomena such as regression to the mean” (p. 165).

In research using a vignette-based methodology, Watkins et al., (2006) demonstrated that participants reported less gratitude and were less willing to help their benefactor in a condition in which the applicability of the norm of reciprocity was enhanced through an explicit statement about the benefactor’s self-interested individual expectation of a return than in a condition in which the benefactor presented themselves as expecting nothing in return. Watkins et al., (2006) had participants read a vignette that asked them to imagine being helped by a benefactor who indicated either that they: (a) did not expect anything in return; (b) expected only an expression of thanks in the form of a card or written note; or (c) expected not only such an expression of thanks but also a return favor. With each level of increasing self-interested individual expectations of return, participants reported feeling greater indebtedness but less gratitude and showed decreased likelihood of helping the benefactor.

More recently Peng and his colleagues (2018) provided evidence to indicate that gratitude and indebtedness play distinct roles in helping. They claim that indebtedness promotes the restoration of equity through reciprocation, whereas gratitude promotes social bonding through proximity seeking. Evidence congruent with this claim was observed in their survey assessing real-life experiences of being helped by a friend. Their study revealed that gratitude was predicted by the benefit of the favor received but not by its costs, while indebtedness was predicted by the cost of the favor and had a weaker relationship to its benefit. This investigation, however, also yielded what Peng et al., 2018 portrayed as an “unexpected” positive correlation between indebtedness and closeness with the benefactor.

Unanswered questions

In terms of unanswered questions, past research in this tradition has not taken into account the type of reciprocity norm that characterizes everyday social support interactions. As described theoretically by Molm and her colleagues (Molm, 2010; Molm et al., 2012), the norm of reciprocity that applies in everyday social support interactions is based on the unilateral flow of benefits, which contrasts with the bilateral flow of benefits characteristic of market-based transactions. Bilateral flow of benefits involves both parties being aware of the terms of the transaction in advance. In contrast, the unilateral flow of benefits involves benefits being given in the absence of any prior agreement or understanding about when, how, or if the benefits will be reciprocated. Giving of benefits without specification of the nature of the expected return leads to greater uncertainty about whether a benefit will be reciprocated than in cases involving the bilateral flow of benefits. Acts of reciprocation function to reduce this uncertainty as they provide evidence of the beneficiary’s commitment to the relationship, which builds trust with the benefactor. In cases involving unilateral flow of benefits, the norm of reciprocity also involves considerable individual discretion, with the beneficiary not needing to give benefits that are equitable to those received or to give a particular type of benefit (Molm et al., 2010). However, in adopting a methodology that specifies what is owed in return, past research portrays the norm of reciprocity as involving the bilateral flow of benefits. An example of such a portrayal may be seen in Watkins et al.’s (2006) experimental manipulation that portrayed the beneficiary being aware and thinking about the benefactor’s expectations for a return before deciding whether or not to help the benefactor. For example, in their “high expectation” condition, participants were instructed that: “when this friend helps anyone, he or she expects a clear expression of thanks, usually in person and in the form of a card or written note, and they also expect a return favor. You happen to know that your friend is moving next Saturday’’ (p. 221). This kind of statement may make the benefactor’s motives appear calculated and thus give rise to negative feelings about the social interaction. Likewise, the assumption made by Peng et al., (2018) that the norm of reciprocity is oriented toward restoring equity is not applicable to the type of reciprocity norm based on the unilateral flow of benefits that characterizes personal relationships.

In addition to recognizing that, in the case of personal relationships, the norm of reciprocity does not include explicit understandings about what is owed in return and does not require that returns be equivalent to the benefits received, it is important to take into account that reciprocity is normative and thus based on shared social expectations (Antonucci & Jackson, 1990; Groger, 1992; Miller et al., 2014; Uehara, 1995). In past research in positive psychology, however, there has been a tendency to portray reciprocity as based exclusively on the self-interested expectations for return of the benefactor. Such a portrayal may have contributed to the benefactors’ motives for giving benefits appearing selfish and thus as non-compatible with gratitude and helping.

Goals of present investigation

The goal of the present three-study investigation was to assess the role of the norm of reciprocity in helping in ways that reflect the distinctive form that reciprocity takes in everyday social support interactions based on the unilateral flow of benefits and on shared normative understandings. In Study 1, we assessed whether treating reciprocity expectations as normatively based and as tacitly understood, rather than as based on the self-interested expectations for return of the benefactor, leads to greater likelihood of helping, higher levels of gratitude, and more positive impressions of the benefactor. We compared responses to a condition involving explicit self-interested individual expectations for return of the benefactor to conditions involving explicit normatively based reciprocity expectations, and to conditions in which normative expectations for reciprocity were unmentioned or disavowed. Our vignette-based design included the same situations involving friend relationships utilized by Watkins and his colleagues (2006). Adoption of this design made it possible for us to test our claims that the norm of reciprocity is associated with both helping and gratitude and applies even when it is denied by a benefactor or left unstated, as well as our claim that self-interested individual expectations for return of the benefactor undermine helping.

In Study 2, we undertook a behavioral test of the anticipated undermining effect of self-interested individual expectations of return of the benefactor on giving of benefits. The research assessed whether the amount of money reciprocated to a benefactor during an online dictator game was less in the presence as compared with absence of a statement by the benefactor about their self-interested individual expectation for a return. Study 2 extended the vignette-based findings of Study 1 to actual behavior. It also provided a more rigorous test of the assumed undermining effect of self-interested individual expectations of return. In contrast to the procedure in Study 1, Study 2 made no mention of the specific type of return expected by the benefactor or of the opportunity available for reciprocation in the near future. Study 2 also employed the same type of probe to experimentally manipulate social expectations as employed in past behavioral research (Goei & Boster, 2005; Tsang & Martin 2019). This allowed for a more direct comparison between the present results and these past findings.

In Study 3, we compared responses to help that participants had received from their friends. The study enhanced the ecological validity of the investigation by assessing helping in a real-life social support context. It also contributed to an understanding of the complementary functions served by gratitude and indebtedness, while testing the prediction that both emotions enhance the closeness of personal relationships.

Study 1

In Study 1 we tested our claim that helping and positive impressions of the benefactor are associated with expectations of reciprocity that are portrayed as normative as well as with norms of reciprocity that are either explicitly denied by the benefactor or left unstated. We also tested our prediction that self-interested individual expectations of return of the benefactor lead to negative personality impressions of the benefactor that undermine helping. In a vignette-based experiment that portrayed an individual receiving help from a friend with a move, we contrasted reciprocity expectations in four conditions. These conditions varied in whether expectations for reciprocating this help involved: (a) self-interested expectations of return of the benefactor that were explicitly stated (explicit self-interested individual expectation); (b) normative expectations that were explicitly stated (explicit normative expectation condition); (c) normative expectations for reciprocity that were explicitly denied (expectation denied condition); or (d) normative expectations for reciprocity that were unmentioned (expectation unmentioned condition). As our explicit self-interested individual expectation condition, we included the condition created by Watkins et al., (2006) in which a benefactor indicates that they expect a return favor and a thank you card and reference is made to the opportunity for reciprocation provided by the benefactor moving the following weekend. As our explicit normative expectation condition, we created a condition that conveyed this same explicitly stated expectation for a return favor and a thank you card, and mention of the opportunity for reciprocation provided by the friend’s planned move but portrayed the reciprocity expectation as based on a norm held in one’s social group rather than on the self-interested desires of the individual benefactor. As our expectation denied condition, we included Watkin et al.’s (2006) no expectation condition in which the benefactor is portrayed as not expecting anything in return and no reference is made to the friend moving the following Saturday. We assumed that this condition would involve the norm of reciprocity as it involves receipt of an intentionally given benefit, a norm that we assumed continues to apply, even when the benefactor explicitly disavows expecting a return. Finally, as our expectation unmentioned condition, we included Watkin et al.’s (2006) base text that they included in all of their experimental conditions. This base text portrayed the participant receiving help in moving from a friend, with no mention made either of the friend’s expectations for return or of the opportunity for reciprocation provided by the friend themselves moving the following Saturday. Inclusion of this condition enabled us to test our hypothesis that norms of reciprocity are associated with receipt of an intentionally given benefit, and do not require mention either of explicit expectations for return or of a specific future opportunity to reciprocate.

We predicted that the likelihood of helping would be lower, the justifiability of not helping greater, gratitude less, and personality impressions more negative in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition as compared to the other three conditions, which each involved normatively based reciprocity expectations that were either explicitly stated (explicit normative expectation condition), understood to apply even when explicitly denied by the benefactor (expectation denied condition), or understood to apply even when unstated (expectation unmentioned condition). We also predicted that personality impressions of the benefactor would mediate the effect of condition on helping, with the benefactor in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition viewed negatively and this undermining helping.

Participants. We recruited 200 participants from the United States via Amazon’s TurkPrime online marketplace (45% were female). This sample size was determined a-priori using G*Power statistical software to detect an effect size of f = 0.24 with power = 80%. Participants ranged in age from 22 to 75 years old (M = 40.12, SD = 15.44). The majority, 83% were Caucasian, 10% Asian, 7% African American, 3% Hispanic. All conditions and variables collected are reported here. The survey was only made available to participants with IP addresses in the United States and no repeat IP addresses were permitted to participate. No participants were excluded after data collection.

Materials and procedure. We utilized the identical helping situation employed in Watkins and his colleagues (2006), with this situation portraying a student who spontaneously helps a classmate move to a new apartment:

Expectation unmentioned condition. You have met someone in one of your classes, have become fairly well acquainted, and have now known them for three months. You have studied several times together with your new friend, have had coffee on several occasions, and you have enjoyed your conversations. You have found a new apartment which is a better deal for you, and so you decide that you will move to the new apartment. You decide that it’s best to complete the move in one day so you rent a truck to move on Saturday. During the week, your friend asks you what you’re doing on Saturday, and you explain that you’ll be spending the day moving. When Saturday rolls around you rent the truck and drive to your old apartment to begin your move.

When you arrive at your apartment you see your new friend waiting for you, ready to help you move. Your friend helps you for most of the day until all your boxes are transported to your new apartment. The move is completed by 2 pm, when you originally thought that you would finish in the evening.

We treated the above information as the expectation unmentioned condition, as it involves tacitly understood normative expectations to reciprocate the benefits received. We also adopted the above text involving receipt of benefits as the first two paragraphs of the vignette in the remaining experimental conditions, all of which included additional information about the reciprocation expected (shown below).

Participants in the other three conditions read one of the following text endings involving receipt of benefits, with the endings corresponding with their experimental condition (italics added below only for emphasis):

Explicit self-interested individual expectation. As you consider your friend’s help, you remember that others have told you that when this friend helps anyone, he or she expects a clear expression of thanks, usually in person and in the form of a card or written note, and they also expect a return favor. You happen to know that your friend is moving next Saturday.

Explicit normative expectation condition. As you consider your friend’s help, you remember that in your group of friends when one friend receives help from another, it is expected that they provide a clear expression of thanks, usually in person and in the form of a card or written note, and they also provide a return favor. You happen to know that your friend is moving next Saturday.

Expectation denied condition. As you consider your friend’s help, you know them well enough that you feel your friend does not expect any kind of return favor. Your friend’s help was offered simply as a gift without any future expectations on you.

The ending in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition was identical to Watkins and his colleagues’ ‘high expectation’ ending and portrayed the reciprocity expectations as based solely on the self-concerned preferences of the individual benefactor. The ending in the explicit normative expectation condition conveyed these same explicitly stated reciprocity expectations but portrayed them as normatively rather than individually based. The ending in the expectation denied condition was identical to the ‘no expectation’ condition used by Watkins and his colleagues (2006) and consisted of an explicit statement that the benefactor did not expect a return – a condition that we assumed would nonetheless involve a tacit normatively based expectation for reciprocation given that a benefit had been received. The expectation unmentioned condition, which did not include any information about the benefactor’s expectations, provided a situation in which tacitly understood reciprocity norms apply given that a benefit has been received.

To tap likelihood of future helping, we asked participants to rate, on a bipolar 10-point scale, how likely or unlikely they would be to help this friend move the following Saturday. This probe differed slightly from Watkins and his colleagues’ (2006) likelihood of helping measure, which asked a more general question - i.e., the participant’s “inclination to help the benefactor if they saw them in need?” (Watkins et al., 2006, p. 221). We elected to ask about a specific help to encourage participants to think about a concrete need situation, which we felt would provide a more sensitive index of participants’ motivation to reciprocate beyond their desire merely to help in an unspecified need situation. Furthermore, we felt that asking about a specific instance would reduce self-presentation biases, as helping in a specific instance is more discretionary than indicating a general desire to be helpful.

Next, participants rated how indebted and how grateful they would feel to their friend in this situation (these and all subsequent ratings in this study used 0- to 5-point scales). We modelled these scale measures after similar Likert scale measures used in past research on gratitude and reciprocity (e.g., Bartlett & DeSteno 2006; Peng et al., 2018).

To assess personality impressions, participants rated on similar 5-point scales how selfish, altruistic, pushy, thoughtful, rude, and likeable they perceived the benefactor to be. Finally, to assess whether it would be justified to decline to help, we asked participants to imagine that they had declined to help and asked them to rate how justified they would be in not helping. This probe was designed to assess whether reciprocity expectations are viewed as social norms which are unacceptable to violate rather than being considered as purely discretionary forms of behavior.

Results

For the main comparisons, we utilized ANOVA analyses, with condition (4) as a between participant factor, followed up with Bonferroni post-hoc tests. As preliminary analysis revealed no significant gender differences, we dropped this factor from further consideration. Means and 95% confidence intervals for all variables appear in Table 1.

Likelihood of helping. Significant condition differences occurred in reported likelihood of helping the benefactor F (3,200) = 6.760, p < .001, η2 = 0.094. As predicted, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition indicated that they were significantly less likely to help the benefactor than did participants in the other conditions [explicit normative expectation condition (p = .001, d = 0.640); expectation denied condition (p = .002, d = 0.577); expectation unmentioned condition (p = .003, d = 0.620)]. No other significant condition differences occurred.

Emotions. We found significant condition differences in gratitude F (3,200) = 5.309, p = .012, η2 = 0.075. As predicted, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition reported significantly less gratitude than did participants in the other conditions [explicit normative expectation condition (p = .019, d = 0.404); expectation denied condition (p < .001, d = 0.419); expectation unmentioned condition (p = .002, d = 0.627)]. No other significant condition differences occurred. Also, as predicted, significant condition differences occurred in indebtedness F (3,200) = 3.012, p = .031, η2 = 0.044. Participants in the expectation denied condition reported significantly less indebtedness than did participants in the other conditions [explicit normative expectation condition (p = .035, d = 0.550); explicit self-interested individual expectation condition (p = .031, d = 0.425; expectation unmentioned condition (p = .026, d = 0.432)]. No other condition differences reached significance.

Perception of benefactor. To assess personality impressions, we reverse coded the negative traits of selfish, rude and pushy and combined them with the positive traits of altruistic, thoughtful, and likeable to create a “positive personality impression” index. This six-item index had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.840 that decreased with the removal of any one of the six items (See Table 2 for means by condition of the individual traits). We found significant condition differences on this personality index F (3, 200) = 30.258, p < .001, η2 = 0.317. As predicted, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition rated the benefactor significantly lower on the positive personality index than did participants in each of the other conditions (explicit normative expectation condition (p < .001, d = 1.236); expectation denied condition (p < .001, d = 1.357); expectation unmentioned condition (p < .001, d = 1.423)]. No other significant condition differences occurred.

We undertook a mediation analysis to assess the influence of personality impressions on the condition differences observed in likelihood of helping. A significant indirect effect of condition on likelihood of helping occurred through the personality index b = -0.0988, SE = 0.040, 95% CI [-0.177, -0.0203] p = .014. The direct effect of condition on likelihood of helping was non-significant b = 0.0124, SE = 0.094, 95% CI [-0.172, 0.197], p = .896, indicating that personality impressions fully mediated the condition differences in likelihood of helping. We found no significant indirect effect of condition on likelihood of helping through indebtedness b = 0.017, SE = 0.016, 95% CI [-0.015, 0.048.], p = .303, or gratitude b = -0.055, SE = 0.32, 95% CI [-0.116, 0.007] p = .084, indicating that neither indebtedness nor gratitude explained the condition differences in helping. Means and 95% confidence intervals for the individual personality traits appear in Table 2.

Visual inspection of the data Footnote 3 provides some insight into the types of negative personality inferences associated with the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition. The results indicate a trend for altruistic to be rated lower and selfish higher in the explicit self-interested explicit self-interested individual expectation as compared with the other conditions. This suggests that the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition was associated with the benefactor being seen as acting out of self-concerned rather than benevolent motives.

Justifiability of not helping. Significant differences occurred in the justifiability of not helping, F (3, 200) = 3.550, p = .016, η2 = 0.053. As predicted, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition indicated that it would be more justified not to help the benefactor than did participants in the other conditions [(explicit normative expectation condition (p = .019, d = 0.569); expectation denied condition (p = .050, d = 0.504); expectation unmentioned condition (p = .050, d = 0.378)]. No other significant condition differences occurred.

Discussion

The results support our hypothesis that when reciprocity is based on self-interested individual expectations of the benefactor it is experienced aversively and undermines helping and gratitude, whereas it is compatible with helping and gratitude when it is normatively based. Participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition held the most negative view of the benefactor’s personality, with personality impressions mediating the effect of condition on likelihood of helping. Such results provide evidence that the communication of a self-interested individually based expectation of return by the benefactor leads people to form negative personality impressions of the benefactor, which explains the decrease in likelihood of helping in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition compared to the other three conditions. The findings further revealed that, when explicitly stated reciprocity expectations are framed as normatively based, the expectations are viewed in positive terms. This underscores how the normative framing of actions is associated with a positive view of reciprocity.

In addition, the findings demonstrate that reciprocity expectations remain binding even when they are conveyed only tacitly. The finding that both indebtedness and gratitude as well as likelihood of helping did not differ in the expectations unmentioned condition compared to the normative expectations condition indicates that reciprocity expectations are linked to receiving a benefit and do not need to be explicitly invoked to apply. This is reflective of the unilateral flow of benefits characteristic of everyday social support interactions in which a benefit is given in the absence of any communication or prior understanding about the specific return expected by the benefactor. In turn, the finding that the expectation denied condition reduced indebtedness but did not undermine the likelihood of helping or affect the justifiability of declining to help underscores the prescriptive aspects of reciprocity. Although a benefactor may disavow any expectation of reciprocation, lowering the extent to which the beneficiary reports feeling indebtedness, fulfilling the norm of reciprocity remains obligatory, as observed in the likelihood of helping being as high and it being considered as unjustified not to help in the expectation denied condition as in the other conditions.

Finally, mediation analysis revealed that personality impressions of the benefactor fully mediated the relationship between condition and helping, with gratitude and indebtedness not explaining the condition differences. This suggests that reduction in helping occurs as a result of self-interested individual expectations held by the benefactor leading to negative personality impressions being formed of the benefactor, and not from indebtedness undermining helping as past research has suggested.

Study 2

Study 1 provided evidence that reciprocity is normative and tacitly understood in everyday social support situations involving the receipt of a benefit, with norms of reciprocity applied even when unstated or disavowed by the benefactor. Further, the results indicated that self-interested individual expectations for return held by the benefactor tend to be experienced negatively and may be responsible for the decrease in helping that past research has attributed to indebtedness. In terms of limitations, however, Study 1 assessed responses to a vignette situation, rather than assessing actual behavior. Also, whereas Study 1 employed the identical manipulation utilized by Watkins et al., (2006) in our explicit self-interested individual expectation condition, this manipulation may have unduly influenced responses, as it mentioned both the exact nature of the return expected and the availability of an opportunity for reciprocation. It is unclear whether this same kind of effect would be observed if a benefactor indicated their self-interested expectation for return in a less expansive way that did not specify either the type of return expected or the availability of an opportunity to reciprocate. In Study 2, we assessed giving of benefits in an online behavioral game in which self-interested individual expectations for return were presented in this less expansive way that did not specify the type of return expected or mention an opportunity for reciprocation. Adoption of this methodology provided a more rigorous test of the anticipated undermining effects of self-interested individual expectations for return by assessing a situation that involved a less explicit manipulation and entailed actual behavioral benefits. Further the use of the same probe to manipulate social expectations as employed in past research (Goei & Boster, 2005; Tsang & Martin 2019) allowed for more direct comparison of the present findings to these earlier studies.

In Study 2, a participant and a pre-programmed, but ostensibly real, partner played two rounds of an online dictator game in which they were informed that their partner would decide in the first round how to divide $1 between themselves and the participant, and the roles would be reversed in the second round, with the participant dividing $1 between themselves and their partner. The total earned over both rounds would be added as a bonus to the participant’s and partner’s PROLIFIC accounts. We employed two experimental conditions that we manipulated between-participants. In the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition, the benefactor made an explicit statement about their expectation of a return, but did not specify the nature of this return or mention an opportunity to reciprocate. In the expectation unmentioned condition, no statement about reciprocation was made. Employing these two conditions allowed us to compare the amount of money participants reciprocated to a partner who either had or had not made a statement about the participant’s debt to them. We hypothesized that, in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition as compared with expectation unmentioned condition, participants would give less money to the partner and feel less pleased with the interaction, more slighted by their partner, and rate their partner as less likable. As the benefit given by the partner involved only a small amount of money, we anticipated that levels of indebtedness and gratitude would be minimal and not vary by condition.

Methods

We pre-registered our hypothesis, methods, and analysis plan at:

https://osf.io/5zbdu/?view_only=63414140ace54881a689a2489976e658.

Participants. We recruited 110 participants from the United States using PROLIFIC online participant recruitment. This sample size was chosen based on an a-prior power analysis performed with G*Power using F tests (Fixed effects omnibus one way), assuming an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.28, with a power estimated at 0.80, and an alpha of 0.10, we estimated an approximate sample size of 82 participants. All conditions and variables collected are reported here. The survey was only made available to participants with IP addresses in the United States and no repeat IP addresses were permitted to participate. We excluded 2 participants for expressing skepticism about the premise in their open-ended responses, leaving a final sample of 108. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 69 years old (M = 32, SD = 11.75). with 55% female, 62% Caucasian, 14% African American, 13% Asian, and 9% Hispanic.

Materials and procedure. At the beginning of the online game, participants were asked to wait to be paired with a partner; this wait was preprogrammed to seem long enough to be believable. Participants were instructed that there would be two rounds of the game, and, in each round, one person would be the divider and would be given $1 to split between themselves and their partner and that, in the following round, the roles would be reversed. In each round, a chat-box was made available for players to communicate with each other. Next, after another programmed brief wait, all participants were informed that their partner would be the divider first and that their partner had elected to give them 30 cents of their dollar. This amount was chosen to demonstrate enough of a risk on the part of the divider as to be perceived as cooperative but not an amount that would raise suspicion. At this point, half of the participants (explicit self-interested individual expectation condition) received a chat message from their partner saying “you totally owe me now”. This prompt was adopted from similar text used in past behavioral research on gratitude and indebtedness (Goei & Boster, 2005; Tsang & Martin 2019Footnote 4). The remainder of the participants (expectation unmentioned condition) received no message from their partner. The expectation unmentioned condition used the identical manipulation employed in this condition in Study 1, which established that receipt of an intentionally given benefit involves reciprocity expectations, even without those expectations being explicitly communicated. Given that the goal of the present study was to identify the impact of succinct self-interested individual expectations for reciprocation on helping, it was unnecessary to include the expectation denied and explicit normative expectation conditions assessed in Study 1. All participants next proceeded to the second round in which it was their turn to play the role of the divider and to divide the $1 they had been given between themselves and their partner. The amount of money participants accumulated by the end of the two rounds was paid to participants as a bonus through PROLIFIC.

After completion of the two rounds, participants were asked some questions regarding their gaming experience. Using an open-ended probe, we asked participants to describe their reasons for choosing the amount of money they gave to their partner in the second round. This question was used to screen out any participant who expressed skepticism about whether they were interacting with a real partner, with only two participants excluded as noted earlier. Next, on unipolar 0-5-point scales, participants rated how grateful, indebted, pleased, and slighted, if at all, they felt after receiving the 30 cents from their partner in the first round. Finally, participants were asked, on a 10-point bipolar scale, how likeable/unlikeable they thought their partner was.

Results

As per our pre-registration, we employed ANOVA to test for condition differences. As preliminary analysis revealed no significant gender effects, and because we had no specific hypotheses related to gender, we dropped this factor from further consideration.

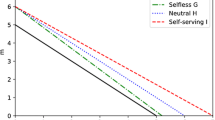

As predicted, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition gave significantly less money to their partner than did those in the expectation unmentioned condition F(1, 108) = 7.974, p = .006, η2 = 0.070. The money donated to the partner in each condition appears in Fig. 1.

Also as hypothesized, participants in the explicit self-interested individual expectation condition reported feeling significantly less pleased F(1, 108) = 2.873, p = .093, η2 = 0.026; more slighted F(1, 108) = 3.722, p = .056, η2 = 0.034; and that their partner was less likeable F(1, 108) = 8.824, p = .004, η2 = 0.077 than did participants in the expectation unmentioned condition. As anticipated based on the low value of the money received, no significant effect of condition occurred on gratitude F (1, 108) = 0.230, p = .633, ηp2 = 0.002, or indebtedness F (1, 108) = 0.552, p = .459, ηp2 = 0.005. Means and 95% confidence intervals for all variables appear in Table 3.

Discussion

As predicted, the benefactor was seen as less likeable and there was a reduction in the amount of money reciprocated in the self-interested individual expectation condition as compared with the expectation unmentioned condition. Participants who were told by their partner that “you totally owe me now” reciprocated less of their earnings to their partner than did participants who heard no statement from their partner. In this way, Study 2 added a behavioral demonstration of the reduction in willingness to help associated with self-interested individual expectations for return. It also demonstrated that the undermining effects on helping of self-interested individual expectations for return occur even in an experimental manipulation that only mentions the general expectation to reciprocate and does not specify the type of reciprocation expected or the availability of opportunities to reciprocate.

The present findings are partially congruent with findings observed by Tsang & Martin (2019) who employed the same type of probe to embody self-interested individual expectations for reciprocation. Tsang and Martin employed a “now you owe me” probe as their “egoistic” note condition which they portrayed as involving a “selfish motivation to reciprocate the favor” and contrasted it with a “benevolent” note condition, which they portrayed as involving acting “out of sympathy”. The Tsang and Martin study is not directly comparable to the present experiment given their use of a different comparison condition which, in their case, involved chance reciprocation. However, like in the present study, Tsang and Martin also did not observe significant condition differences in either gratitude or indebtedness.

Study 3

Study 1 provided vignette-based evidence that indebtedness does not undermine helping, but rather is compatible with both helping and gratitude when portrayed in ways that reflect its normative character. Study 2 demonstrated in a lab-based behavioral experiment that expectations of return that are based on self-interested individual expectations undermine the giving of benefits relative to expectations of return that are based on tacit norms. To assess these types of issues in a more ecological valid way, in Study 3 participants were asked to describe their reactions and behavior in everyday situations in which they experienced either gratitude or indebtedness after receiving help from a close friend.

In designing the methodology of Study 3, we judged that a stringent test of our hypotheses could be achieved by asking participants separately about either gratitude or indebtedness and exploring the degree of any overlap and commonality in the resulting responses and emotions reported. In a between-participant manipulation, we asked participants to describe an everyday situation in which they had received help from one of their close friends and in which, depending on their experimental condition, they had experienced either gratitude or indebtedness. We followed this with a series of questions tapping participants’ feelings and perceptions of that situation.

One goal of Study 3 was to extend the findings of Studies 1 and 2 to a real life social support context. We anticipated to show that, in everyday helping among friends, indebtedness is compatible with gratitude and does not undermine helping. We also anticipated to show that individuals conceptualize gratitude and indebtedness as both involved in everyday helping situations.

An additional goal of Study 3 was to identify the roles played by indebtedness and gratitude in helping. We predicted that only indebtedness and not gratitude would predict reciprocation. This prediction is congruent with recent findings by Peng and his colleagues (2018). However, whereas Peng et al. (2018) concluded that reciprocity promotes equity restoration, we argue that, in the type of reciprocity characteristic of everyday social support, returns do not need to be equivalent to the benefits received but are linked to reciprocation more generally.

A third goal of Study 3 was to identify the roles of both gratitude and indebtedness in relationship building. We predicted that perceptions of the help received as freely given (i.e., given because the friend wanted to help) will be associated with relationship closeness, with this effect fully mediated by gratitude. This prediction is congruent with evidence that gratitude is more closely associated with felt voluntary helping than with helping that is responsive to self-interested individual expectations for return (Goei et al., 2003; Goei & Boster, 2005).

Whereas theoretical claims have been made that only gratitude and not also indebtedness promotes relationship building (Algoe, 2012; Algoe et al., 2008; Fredrickson, 2004; Peng et al., 2018), we expected to identify a link between indebtedness and relationship closeness. We predicted that the perceived significance of the help received would be associated with relationship closeness, with this relationship mediated by indebtedness. We based this prediction on theoretical work by Molm and her colleagues (e.g. Molm, 2010; Molm et al., 2000) who argue that, in contexts involving the unilateral flow of benefits, reciprocation builds trust by reducing the uncertainty associated with whether benefits will be reciprocated

Methods

Participants. We recruited 134 participants from the United States using Amazon’s TurkPrime (42% were female). This sample size was chosen by conducting a power analysis using G*Power statistical software set to detect a medium effect size (F = .25) with 80% power. All conditions and variables collected are reported here. The survey was only made available to participants with IP addresses in the United States and no repeat IP addresses were permitted to participate. 6 participants were excluded for providing gibberish or copy-pasted responses to the initial recall prompt leaving a sample of 128. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 66 years old (M = 32, SD = 8.83) 78% Caucasian, 7% African American, 7% Asian American, 7% Hispanic, 1% other.

Procedure. In a between-participant manipulation, we asked participants “to recall a time in which you experienced feelings of gratitude (indebtedness) toward a close friend in response to a help they gave you. Please describe this situation and specifically what caused you to feel this way”. We next asked participants to rate the levels of gratitude and of indebtedness that they felt, using two counter-balanced 5-point Likert scales. These scales were similar to Likert scale measures used to assess gratitude and indebtedness in Study 1 and in past related research (Barlett et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2018). We also asked participants if they had reciprocated the help they received, beyond saying thank you. The phrasing of this probe is similar to that used in past research on reciprocity (Miller et al., 2014). To provide a measure of the significance of the help narrated in each condition, we asked participants to rate, using ‘0’ to ‘4’ point Likert scales, the levels of emotional investment, time commitment, physical effort and financial expenditure involved in the help received.

We also asked participants to rate, on a ‘0’ to ‘5’ point Likert scale, how close they feel to the friend who helped them. To tap how voluntary participants felt the help was, participants were asked to rate, on a ‘0’ to ‘5’ point Likert scale, the extent to which their friend helped them because they wanted to. As a final question, participants rated, on a 5-point Likert scale, the degree of overlap they perceive gratitude and indebtedness to have: “I almost never/ rarely/ occasionally/ frequently/ almost always/ feel both gratitude and indebtedness simultaneously.”

In later content analysis, a research assistant, blind to the hypotheses of the study, coded the open-ended descriptions of what led the participant to feel either gratitude or indebtedness (depending on their experimental condition). A subset of 20 cases was also coded by the first author, obtaining an interrater reliability of 87.2% (k = .872, p = < .001). The coding scheme included two categories: a) benefactor effort; and b) personal meaning to recipient. The benefactor effort category referenced the length to which the benefactor went in providing the help (e.g., “He spent an entire day of hard labor helping me” or “He spent a couple of hours helping me move. This was not only physically laborious, but a huge suck of time.”). In turn, the personal meaning to recipient category referenced ways the help addressed the particular needs of the participant and alleviated their distress (e.g. “Their help made the move in a day possible and took the load off our shoulders” or “I was feeling pretty helpless since I did not have a vehicle …It was a relief for my friend to be able to help me”). These two coding categories were not mutually exclusive.

Results

Providing evidence on the comparability of the helping situations narrated, ANOVA revealed no condition differences in the closeness of the friendship (p = .587, η2 = .000) or in how voluntary the help was perceived to be (p = .425, η2 = .005). MANOVA on the significance of the help revealed no condition differences in the rated emotional investment (p = .695, η 2 = .001), time commitment (p = .831, η 2 = .000), physical effort (p = .709, η 2 = .001) and financial cost (p=,.332 η 2 = .007), involved. For use in subsequent analyses, we averaged these four measures to create an index of overall significance. (See Table 4 for means and 95% confidence intervals).

Together, these analyses provided evidence of considerable comparability in the types of behaviors narrated in each condition.

Gratitude and indebtedness in helping. Supporting our hypothesis that indebtedness is seen as compatible with gratitude, ANOVA further revealed that no condition differences occurred in the reported levels of either indebtedness (p = .076, η 2 = .022) or gratitude (p = .065, η 2 = .025). Additionally, no condition differences occurred in the overlap participants associated with the emotions of gratitude and indebtedness (p = .764, η 2 = .001). Collapsing across conditions, the mean rating given of their overlap (M = 3.57 on the 0–4 scale) corresponded with a Likert scale rating between “I frequently feel both gratitude and indebtedness simultaneously” and “I almost always feel both gratitude and indebtedness simultaneously.” Such findings indicate that people consider indebtedness and gratitude as co-occurring.

To test our hypothesis that indebtedness does not undermine helping, we analyzed reciprocation. A binary regression indicated that participants were equally likely to have reciprocated, beyond just saying thank you, after receiving the help Wald χ2 (1) = 2.01, p = .156, R2 = .0695, with the majority of participants in each condition reciprocating or intending to reciprocate [indebtedness condition (79%), gratitude condition (73%)]. These findings indicate that reciprocating help is equally likely to occur in situations associated with gratitude as compared with indebtedness.

We also tested our hypothesis that only indebtedness and not gratitude predicts helping. Congruent with this prediction, a binary logistic regression revealed that only indebtedness b = .651, SE = .208, p = .002, R2 = .135 and not gratitude b = .375, SE = .274, p = .167 predicted whether participants had reciprocated or intended to reciprocate the help.

Relationship building. We undertook correlational analyses as a first step in examining the hypothesized links between gratitude, indebtedness, and relationship building. This analysis revealed not only that gratitude was significantly correlated with indebtedness (r = .319**) but that significant correlations occurred both between gratitude and closeness (r = .257**) and between indebtedness and closeness (r = .231*).

To test the specific mediational pathway that we predicted to occur between gratitude and relationship building, we examined the links between the voluntary nature of the help received, gratitude, and closeness with the benefactor. Regression analysis indicated that the voluntary nature of the help predicted closeness (b = .120, SE = .040, t (128) = 2.995, p = .003, R2 = .066). The mediation analysis, however, revealed a significant indirect effect of voluntary nature of the help received on closeness through gratitude b = 0.0761, SE = .020, 95% CI [0.0033, 0.074] p = .043, with the direct effect of the voluntary nature of the help on closeness becoming no longer significant b = 0.1745, SE = .044, 95% CI [-0.004, 0.167], p = .062. These results indicate that gratitude significantly mediated the relationship between the voluntary nature of the help received and closeness with the benefactor. This suggests that gratitude serves to highlight the intention of the benefactor to be helpful, which, in turn, enhances relationship closeness. Additionally, there was no significant indirect effect of this relationship between the voluntary nature of the help and closeness through indebtedness (b = 0.0155, SE = .011, 95% CI [0.0052, 0.036] p = .142), indicating that indebtedness does not mediate this relationship.

In turn, to test the mediational pathway that we predicted to occur between indebtedness and relationship building, we examined the links between the significance of the help received, indebtedness, and closeness with the benefactor. Regression analysis indicated that the significance of the help received predicted closeness (b = .263, SE = .070, t (128) = 3.0776, p < .001, R2 = .101). The mediation analysis, however, revealed a significant indirect effect of significance of the help received on closeness through indebtedness b = 0.0710, SE = .011, 95% CI [-5.15e-4, 0.0427] p = .045, with the direct effect of the significance of the help on closeness becoming no longer significant (b = 0.0318, SE = .028, 95% CI [-0.046, 0.065], p = .732). These results indicate that indebtedness significantly mediated the relationship between the significance of the help received and closeness with the benefactor. This suggests that the significance of the help received enhances indebtedness, which provides assurance that reciprocation will be made thus promoting closeness. Additionally, there was no significant indirect effect of this relationship between the significance of the help received and closeness through gratitude b = 0.0530, SE = .036, 95% CI [-0.0176, 0.122], p = .14, indicating that gratitude does not mediate this relationship.

Finally, qualitive coding of the open-ended descriptions of what led the participant to feel either indebtedness or gratitude revealed that participants in the indebtedness condition (46%) mentioned the benefactor’s effort more frequently than did participants in the gratitude condition (25%) Wald χ2 (1) = 5.296, p = .021, R2 = .0395, whereas participants in the gratitude condition mentioned the personal meaning of the help received more frequently (51%) than did participants in the indebtedness condition (31%) Wald χ2 (1) = 6.432, p = .001, R2 = .0309. These findings may be seen to be congruent with the results of the mediational analysis. The reference to the effort that the benefactor expended in giving the help is related to the concern shown about the significance of the benefactor’s action in the indebtedness condition. Likewise, the reference to the personal meaning of the help is related to its perceived voluntary nature in the gratitude condition, with the beneficiary seen as offering help that was personalized to the beneficiary’s situation and thus well suited to addressing their needs.

Discussion

Considerable comparability occurred in the situations narrated, with no condition differences observed in closeness of the friendship, how much the friend wanted to help, or in the significance of the help received. Participants who were asked to think of a situation that led them to feel gratitude reported feeling as indebted as did participants asked to think of a situation that led them to feel indebted, and vice versa. Additionally, participants in both conditions did not differ in their perceptions that gratitude and indebtedness co-occur in everyday helping. Congruent with recent findings (Peng et al., 2018), our research also provided evidence that indebtedness was uniquely linked to helping. Regression analysis revealed that only indebtedness and not gratitude predicted reciprocation.

The open-ended responses showed that participants in the gratitude condition focused on whether the help provided was tailored to their individual needs. These results suggest that gratitude contributes to the communal feel of close relationships by strengthening the benevolent motives that are involved in helping. Our findings also support past claims that gratitude arises in cases in which individuals are motivated by a desire to be helpful (MacKenzie et al., 2014; Tsang, 2006) and that it is associated with relationship enhancement Algoe, 2012; Bartlett et al., 2012; Frederickson, 2004). Whereas these links have been documented in past research, the present results show that gratitude mediates the link between the voluntary motives of the helper and the increase in relationship closeness. Gratitude is associated with the help given being experienced subjectively as freely given. The present claim is compatible with theories of internalization in self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2017), which highlight the importance of norms being internalized so that they are subjectively experienced as freely given rather than as controlling.

The present findings also imply that it is not only gratitude but also indebtedness that strengthens personal relationships. The open-ended results revealed that indebtedness led participants to focus on the effort involved in giving the help. This did not involve assessment of equity or a comparison of equivalence between the benefits given and those to be reciprocated. Rather the focus on effort entailed an acknowledgement of the sacrifice involved in giving the benefits, which strengthened the personal bond existing between the parties involved. Compatible with the claims of Molm and her colleagues (2012), these results suggest that indebtedness sensitizes individuals to the work expended in giving the help, which builds trust and closeness in the relationship by reducing the uncertainty about reciprocation.

It is unlikely that the present results can be fully explained in terms of participants failing to distinguish between gratitude and indebtedness and instead treating these emotions as synonymous. We assessed the emotions using Likert scales that did not include operational definitions of each construct. In adopting this method, we were following the identical approach employed not only in the other studies in the present investigation but also in much past research (e.g., Bartlett & DeSteno 2006; Peng et al., 2018; Tsang, 2007; Tsang & Martin, 2019). This strategy was ecologically advantageous in that our interest was in assessing how participants spontaneously apply these terms in everyday social support contexts. However, our use of a between-participant design made the commonalities we observed in gratitude and indebtedness less prone to social desirability effects than would have been the case with a within-participant design. Also, in identifying differences in the effects of gratitude and reciprocity both in the quantitative and open-ended responses, our findings do not support a claim that people treat these emotions as indistinguishable.

Taken together, the results of Study 3 point to the compatibility of gratitude and indebtedness as well as the distinct roles they each play in the social support that occurs in personal relationships. The results imply that gratitude and indebtedness co-occur in everyday helping and that both serve relationship building functions.

General discussion

The present investigation provides insight into the roles of reciprocity and indebtedness in everyday social support and identifies factors that have contributed to the downplaying of reciprocity in much past psychological research. Using a vignette-based experimental design, Study 1 established that when reciprocity is framed in ways that reflect its normative character, it is associated with greater likelihood of helping, enhanced gratitude, and more positive personality impressions of the benefactor than when it is portrayed as grounded solely on self-interested individual expectations of the benefactor. Study 2 provided a behavioral test of the undermining effect of self-interested individual expectations of return by demonstrating, in an online game, that players gave more money to their exchange partner, reported being more pleased with the interaction, and rated their partner more positively when reciprocity expectations were unmentioned by the partner as compared with portrayed as self-interested individual expectations. Examining real life helping among friends, Study 3 provided evidence that indebtedness is compatible with gratitude and that it uniquely predicts helping. Results also indicated that both gratitude and indebtedness promote relationship closeness, with gratitude associated with the help received being voluntarily given and oriented toward meeting the other’s needs, and indebtedness signaling a commitment that reciprocation will be made for the help received. Together, the studies provided evidence that gratitude and indebtedness have a similar influence across varying levels of relationship, including recently formed friendships (Study 1), unknown partners in a collaborative experimental task (Study 2) and established friendships (Study 3). Overall, the investigation indicated that in everyday social support, reciprocity is normatively based, and associated with helping and relationship closeness.

The present results highlight the importance of recognizing that an individual’s acknowledgement of indebtedness is not required to tap the type of reciprocity concerns that arise in personal relationships. As demonstrated in Study 1, in the case of personal relationships a helper stating that they have no expectations of a return lessens felt indebtedness; however, it does not reduce the applicability of the norm of reciprocity. The expectation to reciprocate the benefit received persists even when a helper denies expecting a reciprocation, as reciprocation is normative and thus not something that can be disavowed by the individual helper.

The present considerations also highlight the need to recognize that the obligation to return is not what distinguishes situations eliciting gratitude from those eliciting indebtedness, but rather that both gratitude and indebtedness may be implicated in the same type of situations. In early theorizing by Heider (1958) as well as in more recent work on gratitude (e.g., Watkins, 2006; Tsang, 2019), the claim was made that it is the sense of obligation that distinguishes situations involving gratitude from those involving indebtedness. These theorists acknowledge that both emotions may arise in situations in which a benefactor intentionally gives a benefit to a recipient. However, they maintain that it is in situations “where the benefactor obliges the beneficiary to be grateful” (Watkins et al., 2006, p. 219) that the beneficiary experiences more indebtedness and less gratitude. It is further assumed that gratitude arises only in cases in which the beneficiary is acting out of a concern with promoting the other’s welfare, with normative expectations to reciprocate absent. However, the present investigation demonstrates that individuals adopt multiple motives simultaneously, with normative motives to reciprocate coexisting with concerns to be responsive to the other’s needs. The present investigation also implies that it is important to avoid the practice adopted in much past research of portraying reciprocity expectations as stemming exclusively from the self-interested individual inclinations of the benefactor. When portrayed in this way, reciprocity expectations tend to be seen as controlling. The findings in past research that reciprocity expectations are associated with lesser helping is explicable based on the expectations being portrayed in this self-interested form.

It is also important to recognize that adherence to norms of reciprocity may be based on individually held expectations that involve benevolent concerns. Norms of reciprocity may be so fully internalized by individuals that they are subjectively experienced as compatible with the individual’s personal values.

In terms of directions for future research, it would be valuable to undertake studies that test the present claim that reciprocity expectations differ in the extent to which individuals have internalized them. This type of research, which would draw on the methods of self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2017), would provide insight into the extent to whcih individuals subjectively experience fulfilling reciprocity expectations as congruent with individual agency. It also would be important to identify situations in which indebtedness and gratitude are not linearly related, such as cases in which the help received varies in importance (e.g., Oishi et al., 2019). Finally, it is vital to address limitations of the present study of everyday helping (Study 3), which uncovered considerable shared variance in gratitude and indebtedness, even while identifying their distinct correlates. This issue can be addressed in future research by assessing a wider range of helping situations, in which the cost of the help received and the relationships between the parties involved varies. Such research could provide insight into the extent to which the role of these two emotions in everyday helping is even more distinct than observed here.

More generally, it is important to develop more positive views of the role of social norms in motivating behavior. Within psychology, social norms are often treated solely as constraints on behavior that lead people to behave in ways that are motivated by a self-interested desire to avoid social sanctions (Markus & Kitayama, 1994). It cannot be concluded, however, that social norms, such as reciprocity expectations, are necessarily experienced subjectively as onerous to fulfill or are antithetical to other-oriented feelings, such as closeness and concern with the other’s welfare. Work on self-determination theory has shown that individuals may so fully internalize social expectations that they subjectively experience their behavior in agentic terms as freely chosen and as reflecting their values even as they are complying with a particular social norm (e.g., Ryan & Deci 2017; Miller et al., 2011). The type of flexible reciprocity norms that govern everyday social support interactions with friends and in other personal relationships steer people to help one another, and enhance relationship closeness. Rather than pitting the effects of gratitude and indebtedness against each other, a fuller understanding of everyday social support may be achieved by recognizing that both gratitude and indebtedness play integral roles in helping in the case of personal relationships.

Notes

We use the term ‘personal relationships’ to reference friends, romantic partners, and family members.

By ‘everyday social support contexts’, we refer to the provision of help that occurs among friends, romantic partners and family members.

As we had not made predictions at the level of the individual personality traits, our analysis here is based solely on visual inspection of trends rather than on quantitative analysis.

References

Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6, 455–469. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00439.x

Algoe, S. B., Haidt, J., & Gable, S. L. (2008). Beyond reciprocity: Gratitude and relationships in everyday life. Emotion, 8, 425. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.425

Antonucci, T. C., & Jackson, J. S. (1990). The role of reciprocity in social support. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Wiley series on personality processes. Social support: An interactional view (pp. 173–198). Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons

Baker, W. E., & Bulkley, N. (2014). Paying it forward vs. rewarding reputation: Mechanisms of generalized reciprocity. Organization Science, 25, 1493–1510. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0920

Bartlett, M. Y., & DeSteno, D. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: Helping when it costs you. Psychological Science, 17, 319–325. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01705.x

Bartlett, M. Y., Condon, P., Cruz, J., Baumann, J., & DeSteno, D. (2012). Gratitude: Prompting behaviours that build relationships. Cognition & Emotion, 26, 2–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.561297

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons, & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Goei, R., & Boster, F. J. (2005). The roles of obligation and gratitude in explaining the effect of favors on compliance. Communication Monographs, 72, 284–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750500206524

Goei, R., Lindsey, L. L., Boster, F. J., Skalski, P. D., & Bowman, J. M. (2003). The mediating roles of liking and obligation on the relationship between favors and compliance. Communication Research, 30, 178–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650202250877

Groger, L. (1992). Tied to each other through ties to the land: Informal support of black elders in a Southern U.S. Community. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 7, 205–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00122509

MacKenzie, M. J., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2014). You didn’t have to do that: Belief in free will promotes gratitude. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(11), 1423–1434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214549322

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1994). A collective fear of the collective: Implications for selves and theories of selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 568–579. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205013

Miller, J. G., Bland, C., Källberg-Shroff, M., Tseng, C., Montes-George, J., Ryan, K. … Chakravarthy, S. (2014). Culture and the role of exchange vs. communal norms in friendship. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 79–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.02.006

Miller, J. G., Das, R., & Chakravarthy, S. (2011). Culture and the role of choice in agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 46–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023330

Molm, L. D. (2010). The structure of reciprocity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73, 119–131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272510369079

Molm, L. D., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 1396–1427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/210434

Molm, L. D., Whitham, M. M., & Melamed, D. (2012). Forms of exchange and integrative bonds: Effects of history and embeddedness. American Sociological Review, 77(1), 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411434610

Oishi, S., Koo, M., Lim, N., & Suh, E. M. (2019). When gratitude evokes indebtedness. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11(2), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12155

Peng, C., Nelissen, R. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2018). Reconsidering the roles of gratitude and indebtedness in social exchange. Cognition and Emotion, 32, 760–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1353484

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Press

Schwartz, B. (1967). The social psychology of the gift. American Journal of Sociology, 73, 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/224432

Tsang, J. (2006). The effects of helper intention on gratitude and indebtedness. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 198–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9031-z

Tsang, J. A. (2007). Gratitude for small and large favors: A behavioral test. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 2(3), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701229019

Tsang, J. A., & Martin, S. R. (2019). Four experiments on the relational dynamics and prosocial consequences of gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(2), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388435

Uehara, E. S. (1995). Reciprocity reconsidered: Gouldner’s ‘moral norm of reciprocity’ and social support. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12, 483–502. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595124001

Visser, M. (2008). The gift of thanks. Toronto: Harper Collins

Watkins, P., Scheer, J., Ovnicek, M., & Kolts, R. (2006). The debt of gratitude: Dissociating gratitude and indebtedness. Cognition & Emotion, 20, 217–241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500172291

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Note

Neither authors have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research, and APA ethical standards were followed in the conduct of the study. We would like to acknowledge William Hirst for his feedback on a prior draft of this manuscript. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Note

The authors do not have any interests that might be interpreted as influencing the research, and APA ethical standards were followed in the conduct of the study. All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adams, M.M., Miller, J.G. The flexible nature of everyday reciprocity: reciprocity, helping, and relationship closeness. Motiv Emot 46, 461–475 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09949-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09949-y