Abstract

Gratitude and indebtedness have often been equated in psychology. Emerging research, however, suggests that these emotions are experienced differently and occur in response to different situations (Gray, Emmons, & Morrison, 2001). The current set of experiments investigated the effects of helper intention on grateful and indebted reactions to a favor. Study 1 utilized scenario methodology to present participants with a favor that was given with benevolent or ulterior motives. Participants felt significantly more grateful when the helper had benevolent intentions. Reactions of indebtedness did not vary as a function of helper intention. In Study 2, participants recalled favors that had been done for them for either unselfish or selfish reasons. Participants reported significantly more gratitude for the favor when they were instructed to recall an unselfish favor. Levels of indebtedness were not affected by helper intention. Study 3 provided participants with an ambiguous favor scenario to better assess individuals' natural reactions to receiving help, and replicated the results of Study 1. Together, these three experiments provide support for differences between grateful and indebted emotions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Individuals may have different reactions to the receipt of aid (Fisher, 1983). For example, an employee might feel grateful to a coworker who provides much needed help on a difficult project. If that coworker is perceived to have helped just to make herself look good in front of the boss, however, the employee might instead react with negative emotions such as resentment or indebtedness rather than gratitude. The current paper examines the differences between the emotions of gratitude and indebtedness, investigating how helper intention differentially affects these two potential reactions to aid.

Gratitude

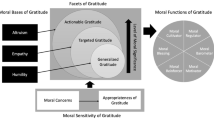

Gratitude is one common reaction to aid (Gallup, 1998). Ortony, Clore, and Collins (1988) posited that gratitude was a compound emotion that arose from the admiration of a praiseworthy action (intention) and the joy experienced when that action is desirable (or valuable) to the self. Emmons and Crumpler (2000) described gratitude as “an emotional response to a gift” (p. 56), adding that gratitude is an interpersonal emotion that is felt toward other people or entities, and not toward oneself. McCullough (2002) defined gratitude as “a cognitive-affective response to the recognition that one has been the beneficiary (or, in some cases, only the intended beneficiary) of someone else's good will” (p. 303). Research has demonstrated that individuals are more likely to experience gratitude when they receive a favor that is perceived to be (1) valued by the recipient, (2) costly to the benefactor, (3) given by the benefactor with benevolent intentions, and (4) given gratuitously (as contrasted with benefits given due to role-based obligations) (e.g., Bar-Tal, Bar-Zohar, Greenberg, & Hermon, 1977; Graham, 1988; Lane & Anderson, 1976; Tesser, Gatewood, & Driver, 1968). The vast majority of this research has relied on scenario methodology (see Tsang & McCullough, 2004, for a summary of the research on gratitude).

Indebtedness

Individuals do not always react to a favor with gratitude; sometimes, feelings of indebtedness result from the receipt of aid. Greenberg (1980) defined indebtedness as “a state of obligation to repay another (p. 4), which arises from the norm of reciprocity, a moral code stating that “(1) people should help those who have helped them, and (2) people should not injure those who have helped them” (Gouldner, 1960, p. 171). In other words, the theory of indebtedness states that when an individual receives a benefit from another, he or she feels obligated to reciprocate the favor. Research has generally supported this claim (e.g., Gouldner, 1960; Regan, 1971; Whatley, Webster, Smith, & Rhodes, 1999).

Differences between gratitude and indebtedness

Although researchers studying reciprocation often equate gratitude with indebtedness (Gray, Emmons, & Morrison, 2001), there are a number of theoretical and empirical differences between the two concepts. First, indebtedness is accompanied by negative emotions such as discomfort and uneasiness (e.g. Greenberg, 1980), whereas gratitude is a positively valenced emotion (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994; Mayer, Salovey, Gomberg-Kaufman, & Blainey, 1991). Second, indebtedness has been found to be associated with self-reported avoidance motivations, whereas gratitude is associated with self-reported prosocial motivations (Gray et al., 2001). Third, indebtedness stems from the norm of reciprocity, whereas gratitude, though perhaps influenced by this norm as well, may go above and beyond a “tit-for-tat” mentality. For example, an individual motivated to reciprocate out of indebtedness may work to return a favor of equal value to the donor, taking the donor's costs into account (Fisher, 1983; Greenberg, 1980). In contrast, people often acknowledge that there are certain individuals toward whom they are so grateful, they could never provide a benefit equal to that which they have received (e.g., gratitude toward one's parents or God) (Roberts, 1991). Therefore, gratitude and indebtedness are not necessarily identical phenomena. Yet, despite these theoretical differences, there has been little research examining the differences between these two potential reactions to aid.

Certain characteristics of the helping situation may determine whether recipients of aid experience gratitude, indebtedness, or both. Ames, Flynn, and Weber (2004) found that one determinant of reactions to aid was the inferred motivations of the helper. Specifically, they found that individuals felt more positively toward future interactions with a helper when they perceived that the helper decided to help them out of positive feelings for them, rather than from a cost-benefit analysis. This effect was mediated by inferred helper mental states, with individuals perceiving helpers to care more about them when the helper decided to help based on positive feelings. They also found that feelings of gratitude were significantly correlated with inferred helper mental states. Thus, gratitude and other reactions to aid may be affected by perceptions of the manner by which helpers make the decision to help and, by extension, the perceived intentions of the helper.

Greenberg and Wescott (1983) also predicted that helper intention would affect reactions to aid. They theorized that the receipt of aid would result in positive affect (such as gratitude) when recipients perceive the aid as a sign of positive regard, but that aid would result in negative affect or indebtedness when recipients perceive the helper as having manipulative or deceitful intentions. Gratitude and indebtedness may therefore be differently affected by perceptions of donor intention.

Watkins, Scheer, Ovnicek, and Kolts (2006) manipulated benefactor expectations of reciprocation in gratitude scenarios and found that as reciprocation expectations increased, participants reported lower levels of gratitude and higher levels of indebtedness. Participants were also more likely to report wanting to help the benefactor in return if the benefactor did not express strong reciprocation expectations.

The present studies

The present set of experiments investigated the effects of perceived intention on feelings of gratitude and indebtedness. Study 1 presented participants with a favor scenario in which the helper had either benevolent or ulterior motives. Study 2 asked participants to recall an actual event in their lives where someone did them a favor for either benevolent or selfish reasons. Study 3 presented participants with a favor scenario in which the helper's motivation remained ambiguous in order to better examine individuals' natural attributional and emotional reactions to favors.

Study 1

Method

Participants

Participants were 93 female and 20 male undergraduates at Baylor University who received extra course credit for their participation.

Procedure

Participants were run in groups of 2–30 individuals. Each participant was given a questionnaire packet containing the study materials. Participants were presented with a scenario and asked to imagine themselves in the scenario situation. Some participants (N=49) were randomly assigned to the following scenario, in which a friend does them a favor for benevolent reasons:

It's the beginning of the semester, and you're standing in line at the bookstore to buy all the books for your classes. You are waiting in line with a friend, and the both of you joke about how long the line is taking. After a long wait, the cashier rings you up, and you find out that the total cost for your books is $400, which is much more expensive than what you expected. You only have $200 in your checking account. As you are standing there wondering what to do, your friend offers to pay the extra $200 for you: “Don't worry about it. I've been in that situation before and it's a real bummer! Let me pay for it and you won't have to stress about getting your books in time for the first exam or anything.” Although your friend isn't rich, you know that your friend can afford the $200. You can tell that your friend is really concerned about you and wants to help you out, so you say yes.

The other participants (N=64) were presented with a similar scenario, except that the last sentence indicated that the friend had ulterior motives for helping the participant, e.g., “You know that your friend is really doing you this favor in order to borrow your car next weekend, but you really need those textbooks so you say yes.”

Following the favor scenario, participants were asked questions about the emotions they would feel in the scenario, including several emotions relevant to gratitude and indebtedness. Participants responded on a 1–7 Likert-type scale (1=Would feel very little of this emotion, 7=Would feel a lot of this emotion). A measure of gratitude was created by combining participant ratings of grateful, thankful, and appreciative (α=89) and a measure of indebtedness was created by combining ratings of indebted and obligated (α=72). Participants were also asked to rate the helper's motivation in the scenario (1=Very concerned about me, 7=Motivated by selfish reasons) and the magnitude of the favor (“How much of a favor do you think the friend did by giving money for the textbooks?” 1=A very small favor, 7=A very big favor).

It was predicted that participants' reactions of gratitude and indebtedness would differ as a function of the intention of the benefactor, with benevolent intentions leading to more gratitude, and selfish intentions leading to more indebtedness.

Results and discussion

Manipulation checks

As expected, participants rated the helper as being significantly less selfish in the Benevolent Motives condition (M=2.14, SD=1.04) compared to the Ulterior Motives condition (M=3.41, SD=1.42), t(10.80)=5.45, p < .001 (p-values for t-tests are two-tailed, unless otherwise indicated). Given the low values in both conditions, however, it seems that participants were reluctant to attribute a large amount of selfishness to the helper in this particular scenario. Participants did not rate the magnitude of the favor differently between conditions (M benvolent=6.39, SD=.95; M ulterior =6.14, SD=1.04; t(111)=1.30, p > .19).

Gratitude and indebtedness

Across the two conditions, participants expressed both a high amount of gratitude (M=6.37, SD=0.79) and indebtedness (M=5.50, SD=1.29). Gratitude and indebtedness were not significantly correlated across conditions, r(111)=.02, p > .20, or between conditions, r(47)benevolent=.10, p > .20; r(62)ulterior=.00, p > .20.

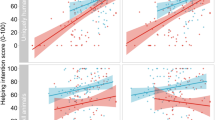

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for gratitude and indebtedness for each condition. Individuals reported feeling significantly more grateful when the helper had a benevolent rather than ulterior motive, t(104.92)=3.31, p < .01, but there were no differences between conditions for indebtedness [t(111)=.40, p > .20].

Correlations were used to test for differences between the relationship of gratitude and indebtedness to motivation. Gratitude was significantly negatively related to motivation condition, r=−.28, p < .01, again demonstrating that participants reported less gratitude when the helper was said to have had ulterior motives for helping. Indebtedness was not significantly correlated with motivation condition, r=.04, p > .20. The correlation between gratitude and condition was significantly different from the correlation between indebtedness and condition, t(110)=2.51, p < .05. Therefore, gratitude varied according to helper intention, whereas feelings of indebtedness did not.

Study 2

Although much gratitude research utilizes scenarios, there are some shortcomings to this methodology. The presentation of favor scenarios helps insure standardization between participants, but scenario research tends to elicit a low level of involvement, and hence has potentially low psychological realism (Hegtvedt, 1990). Additionally, participants who read gratitude scenarios do not necessarily experience grateful emotions (e.g., Graham, 1988; Weiner, Russell, & Lerman, 1978). It is possible that participants are describing their personal theories of gratitude (Weiner, Russell, & Lerman, 1979), but not their actual grateful responses.

To address these methodological shortcomings, in Study 2 participants were asked to recall actual favors that had happened to them in the past. This recall exercise was designed to increase participant involvement, and to remind participants of the actual grateful and indebted emotions that they may have felt during the event. In addition, this second study provided an opportunity to replicate the results of Study 1. In light of the findings of Study 1, it was expected that participants in Study 2 would feel more gratitude if asked to recall an unselfish compared to a selfish favor. Indebtedness was expected to be relatively insensitive to helper intention.

Method

Participants

Partcipants were 76 female and 16 male undergraduates at Baylor University who received extra course credit for their participation. Five additional participants (three from the selfish condition and two from the benevolent condition) were excluded from data analyses because they did not follow instructions about the type of situation to recall (e.g., participants did not write about a situation that had positive consequences).

Procedure

Participants were run singly in laboratory cubicles. They were given a questionnaire packet that contained the study materials. On the first page, participants were asked to remember and write about a situation that happened to them in the past year. Instructions were modified from those given in Ellsworth and Smith (1988) to induce recall of pleasant experiences with other-agency appraisals. Specifically, participants were asked to think of an experience where they felt that “someone else had caused, and was controlling, what was happening in the situation,” and “the positive consequences of this other person's actions were important to you.” In addition, approximately half of the participants (N=45) were asked to think of a situation where “the other person was doing something good for you for unselfish reasons,” (Benevolent condition) whereas the other half of the participants (N=47) imagined a situation where someone did something good for them for selfish reasons (Selfish condition). Participants were asked to take a minute to think back and re-experience the thoughts and emotions that they were feeling during this situation, and they were then instructed to write about the details of the situation on a lined sheet of paper.

Participants were then asked questions about their current emotions in reaction to the situation they were asked to recall. A gratitude scale was constructed from the emotion adjectives grateful, thankful, and appreciative, α=96, and an indebtedness scale was constructed from the emotion adjectives indebted and obligated, α=71. Participants were also asked to rate the helper's motivation in the situation (1=Very concerned about me, 7=Motivated mostly by selfish reasons) and the magnitude of the favor (“How big of a favor do you think the other person did for you?” 1=A very small favor, 7=A very big favor).

Results and discussion

Participants reported a diverse number of favors done for them. Benefactors included friends, romantic partners, parents, and employers. For example, one participant in the Benevolent condition wrote about how her boss gave her a raise and extra hours at work so that she could quickly pay off her large amount of credit card debt. A participant in the Selfish Condition recalled a time when a friend bought her groceries on order to appear generous to her roommate.

Manipulation checks

Participants in the Benevolent condition perceived their helper's motives as being significantly less selfish (M=1.68, SD=1.18) than did participants in the Selfish condition (M=5.25, SD=1.64), t(82.40)=12.35, p < .001. Not surprisingly, participants in Study 2, who recalled actual favors that occurred in their own lives, appeared to make stronger attributions of selfishness to helpers with ulterior motives, compared to participants in Study 1 who were only reacting to a scenario. Also in contrast to Study 1, participants in Study 2 rated the magnitude of the favor done for them as larger in the Benevolent condition (M=6.14, SD=1.03) compared to the Selfish condition (M=3.77, SD=2.00), t(71.34)=7.22, p < .001.

Gratitude and indebtedness

Across conditions, participants expressed a high amount of gratitude (M=5.01, SD=2.04), and lower levels of indebtedness (M=2.78, SD=1.50). In contrast to Study 1, in Study 2 gratitude and indebtedness were significantly correlated between conditions r(90)=.57, p < .001, and within the Selfish, r(46)=.61, p < .001, but not the Benevolent condition, r(42)=20, p=.20.

ANOVAs were conducted to investigate the effects of helper intention condition on gratitude and indebtedness. Because participants were asked to freely recall a favor that had actually happened to them, the size of the favors was not standardized across participants, and differences in favor magnitude emerged, as noted above. Therefore, participant ratings of the magnitude of the favor were entered as a covariate. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for gratitude and indebtedness for each condition. Participants reported significantly more grateful emotions after writing about a favor given unselfishly compared to one given selfishly after controlling for favor magnitude, F(1,89)=21.61, p < .001. There was no significant effect of intention on feelings of indebtedness controlling for favor magnitude, F(1,89)=1.21, p > .20.

Regression analyses were conducted with condition and magnitude of the favor predicting gratitude and indebtedness. Selfish/unselfish condition [β=.32, t(89)=4.65, p < .01] and magnitude of the favor [β=.62, t(89)=9.02, p < .01] both significantly and uniquely predicted feelings of gratitude, R 2=.73, F(2,89)=114.40, p < .001. In contrast, selfish/unselfish condition [β=.13, t(89)=1.10, p > .20] did not significantly predict indebtedness, although magnitude of the favor [β=.42, t(89)=3.69, p < .001] did, R 2=.26, F(2, 89)=15.22, p < .001.

Study 3

Studies 1 and 2 provided consistent evidence for differential effects of intentions on gratitude: Individuals felt little gratitude for a favor that was given selfishly, but more gratitude when the helper acted unselfishly. On the other hand, feelings of indebtedness remained constant and independent of helper intention. This effect was replicated across both favor scenarios and retrospective accounts of favor situations. Both of these studies, however, examined responses to pre-determined helper intention. In Study 1, participants were told the intentions of the helper in the scenario. In Study 2, participants were directly instructed to recall favors that were done for either benevolent intentions or ulterior motives. In these situations, individuals were not allowed to provide their own attributions about helper intention.Footnote 1 Therefore, Study 3 provides a condition where participants are presented with a favor scenario in which the helper has ambiguous intentions, allowing participants to make their own attributions of helper intention. Study 3 also presents an opportunity to replicate the effects found in Study 1.

Method

Participants

Participants were 49 female, 13 male, and 24 individuals of undisclosed genderFootnote 2 who were undergraduates at Baylor University. Participants received extra course credit for their participation.

Procedure

Participants were run in groups of 2–30 individuals. Each participant was given a questionnaire packet containing study materials. Participants were randomly assigned to read one of three scenarios. The Benevolent (N=28) and Ulterior Motives (N=29) scenarios were identical to those presented in Study 1. A third condition replaced the last sentence with a statement that left the helper intention ambiguous: “You really need those textbooks so you say yes. The next weekend that same friend asks you if they can borrow your car to run some errands.” This statement was designed to allow for the possibility of both benevolent intentions and ulterior motives.

The remainder of the dependent measures were identical to the items provided in Study 1, and included measures of gratitude (α=.85), indebtedness (α=.64), helper motivation, and favor magnitude.

Consistent with the results of Studies 1 and 2, it was predicted that perceived benefactor intention would have different effects on gratitude and indebtedness. It was hypothesized that participants would react with more gratitude when they attributed benevolent intentions to the benefactor, and less gratitude when they attributed ulterior motives to the benefactor. In contrast, indebtedness was hypothesized to be relatively insensitive to perceived helper intention.

Results and discussion

Manipulation checks and descriptives

As in Study 1, participants rated the helper as being significantly less selfish in the Benevolent Motives condition (M=.96, SD=.69) compared to the Ulterior Motives condition (M=3.83, SD=1.31). Intention ratings for participants in the Ambiguous Motives condition fell between those in the other two conditions (M=2.34, SD=1.14). Participants in the Ulterior Motives rated the helper as significantly more selfish than did those participants in both the Benevolent Motives [t(42.83)=6.74, p < .01] and the Ambiguous Motives [t(56)=4.59, p < .01] conditions; the Benevolent Motives and Ambiguous Motives conditions, however, were not significantly different from each other, t(46.41)=1.53, p=.13. In contrast to Study 1, ratings of the magnitude of the favor differed between conditions: Participants in the Ulterior Motives condition reported that the favor was significantly smaller (M=5.62, SD=1.21) compared to participants in both the Benevolent Motives [M=6.57, SD=.69, t(44.83)=3.67, p < .01] and the Ambiguous Motives [M=6.24, SD=1.09, t(56)=2.05, p < .05] conditions. The Benevolent Motives and Ambiguous Motives conditions did not differ from one another in ratings of favor magnitude, t(47.55)=1.37, p=.18.

Gratitude and indebtedness

Across the three conditions, participants expressed both a high amount of gratitude (M=6.45, SD=.71) and indebtedness (M=5.30, SD=1.35). Gratitude and indebtedness were significantly correlated only in the Ambiguous Motives condition (r=.42, p < .05); correlations in the Benevolent Motives (r=−.13, p > .20) and Ulterior Motives condition (r=.26, p=.17) were not significant.

ANOVAs revealed that helper intention condition had a significant effect on gratitude [F(2,83)=6.72, p < .01], but not indebtedness [F(2,83)=.18, p > .20]. Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations for gratitude and indebtedness for each condition. Participants felt significantly more grateful in the Benevolent Motives condition compared to the Ambiguous Motives condition [t(41.63)=2.07, p < .05], and marginally less grateful in the Ulterior Motives condition compared to the Ambiguous Motives condition [t(56)=−1.84, p=.07]. In contrast, levels of indebtedness in the Benevolent Motives condition were not significantly different from the Ambiguous Motives [t(55)=.47, p > .20] or the Ulterior Motives condition [t(56)=−.10, p > .20].

The Ambiguous Motives condition was of particular interest in this study because it allowed participants to make their own helper intention attributions. Looking at the Ambiguous Motives condition alone, ratings of selfish intentions were significantly negatively correlated with gratitude, r(27)=−.40, p < .05, but uncorrelated with indebtedness, r(27)=.00, p > .20.

General discussion

The positively-valenced emotion of gratitude was more sensitive to helper intentions: People felt more grateful in response to favors done with benevolent intentions. In contrast, individuals' feelings of indebtedness were not sensitive to helper intention. This may have been because the norm of reciprocity was still operating whether or not a favor was given for benevolent or selfish reasons, and the experience of indebtedness is theoretically tied to the norm of reciprocity (Greenberg, 1980). Presumably, even a selfish favor needs to be reciprocated in some way, whether in word or in deed, and this may cause recipients of both benevolent and selfish favors to feel a certain level of indebtedness to their benefactor.

These different effects on the emotions of gratitude and indebtedness occurred when participants were presented with favor scenarios, as well as when they were asked to remember an actual favor that had happened to them in the past, speaking to the potential robustness of these effects. Additionally, these patterns of effects were also uncovered when participants were presented with an ambiguous favor scenario that allowed them to make their own intention attributions.

Although recall methodology was used in Study 2 in part to address limitations of the scenario methodology used in Studies 1 and 3, Study 2 was not without limitation. Participants in Study 2 were asked to recall a favor that was done for them within the past year; no measure, however, was taken of the amount of time that had passed since the favor had occurred. Therefore, it is possible that recall biases might have affected some of the results. For example, participants recalling favors from further in the past may reconstruct those memories as being more or less pleasant than favors done more recently. Research looking at gratitude in the laboratory could address shortcomings of both scenario and recall research. Laboratory favors, such as receiving resources from another participant, have the advantage of being easily standardized and are potentially involving for participants, and these favors would not be affected by recall biases (Tsang, 2006).

These results underscore differences between the emotions of gratitude and indebtedness. Not only may gratitude and indebtedness be tied to different motivations (Gray et al., 2001), these data demonstrate that these emotions may be affected differently by perceptions of benefactor intention. Additional research is needed to investigate whether these different patterns of gratitude and indebtedness translate into differences in behavioral reciprocation and/or expressions of thanks. Although some research has linked gratitude and indebtedness to thought and action tendencies (Watkins et al., 2006), there are currently no studies that assess differences between gratitude and indebtedness in the frequency and magnitude of behavioral reciprocation for favors. It is possible that individuals may react to a benevolently given favor with gratitude and greater reciprocation, compared to a selfishly given favor that elicits indebtedness and little gratitude. A laboratory study of behavioral reciprocation in reaction to selfish and unselfish favors would be again an especially good method to address these predictions.

Research on gratitude is a small but growing field; research on the differences between gratitude and indebtedness is even rarer. The current set of studies demonstrates that gratitude and indebtedness are not identical emotions, but occur differently in reaction to differences in perceived benefactor intentions. As additional research is conducted to investigate the differences between gratitude and indebtedness, more light will be shed on these two potential reactions to aid.

Notes

The author would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

Lack of gender information for these 24 participants was due to an experimenter error, and not to an unwillingness to disclose gender on the part of the individual participants.

References

Ames, D. R., Flynn, F. J., & Weber, E. U. (2004). It's the thought that counts: On perceiving how helpers decide to lend a hand. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 461–474

Bar-Tal, D., Bar-Zohar, Y., Greenberg, M. S., & Hermon, M. (1977). Reciprocity behavior in the elationship between donor and recipient and between harm-doer and victim. Sociometry, 40, 293–298.

Ellsworth, P. C., & Smith, C. A. (1988). Shades of joy: Patterns of appraisal differentiating pleasant emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 2, 301–331.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (2000). Gratitude as a human strength: Appraising the evidence. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 56–69.

Fisher, J. D. (1983). Recipient reactions to aid: The parameters of the field. In J. D. Fisher, A. Nadler, & B. M. DePaulo (Eds.), New directions in helping (Vol. 1, pp. 3–14). New York: Academic Press.

Gallup, G. H., Jr. (1998 May). Thankfulness: America's saving grace. Paper presented at the National Day of Prayer Breakfast, Thanks-Giving Square, Dallas.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Graham, S. (1988). Children's developing understanding of the motivational role of affect: An attributional analysis. Cognitive Development, 3, 71–88.

Gray, S. A., Emmons, R. A., & Morrison, A. (2001 August). Distinguishing gratitude from indebtedness in affect and action tendencies. Poster presented at the annual meeting ofthe American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA.

Greenberg, M. S. (1980). A theory of indebtedness. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 3–26). New York: Plenum Press.

Hegtvedt, K. A. (1990). The effects of relationship structure on emotional responses to inequity. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53, 214–228.

Lane, J., & Anderson, N. H. (1976). Integration of intention and outcome in moral judgment. Memory and Cognition, 4, 1–5.

Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., Gomberg-Kaufman, S., & Blainey, K. (1991). A broader conception of mood experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 100–111.

Lazarus, R. S., & Lazarus, B. N. (1994). Passion and reason: Making sense of our emotions. New York: Oxford University Press.

McCullough, M. E. (2002). Savoring life, past and present: Explaining what hope and gratitude share in common. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 302–304.

Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1988). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 627–639.

Roberts, R. C. (1991). Virtues and rules. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 51, 325–343.

Tesser, A., Gatewood, R., & Driver, M. (1968). Some determinants of gratitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 233–236.

Tsang, J. (2006). Gratitude and prosocial behavior: An experimental test of gratitude. Cognition and Emotion, 20, 138–148.

Tsang, J., & McCullough, M. E. (2004). Annotated bibliography of research on gratitude. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 291–341). New York: Oxford University Press.

Watkins, P. C., Scheer, J., Ovnicek, M., & Kolts, R. (2006). The debt of gratitude: Dissociating gratitude and indebtedness. Cognition and Emotion, 20, 217–241.

Weiner, B., Russell, D., & Lerman, D. (1978). Affective consequences of causal ascriptions. In J. H. Harvey, W. J. Ickes, & R. F. Kidd (Eds.), New directions in attribution research (Vol. 2). Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum.

Weiner, B., Russell, D., & Lerman, D. (1979). The cognition-emotion process in achievement related contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1211–1220.

Whatley, M. A., Webster, J. M., Smith, R. H., & Rhodes, A. (1999). The effect of a favor on public and private compliance: How internalized is the norm of reciprocity? Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21, 251–259.

Aknowledgments

The author would like to express appreciation to Wade Rowatt for his comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript, and to thank the following individuals for data-collection assistance: Diana Castillo, Aline Defreitas, Courtney Drew, Brandi Glaspie, Amy Harper, Tonya Hyde, Tiara Mason, Vanessa Mizutowicz, Sara Pierce, Maricela Rábago, Kimberly Reeves, and Jason Vollmecke

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsang, JA. The Effects of Helper Intention on Gratitude and Indebtedness. Motiv Emot 30, 198–204 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9031-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9031-z