If you’re helping someone and expecting something in return, you’re doing business not kindness.

Unknown.

Abstract

Reciprocity has been shown to be sensitive to perceived intentions, however, not much is known about the intensity of reciprocal responses to the precise nature of those intentions. For example, a person can strategically appear to be kind while being self-serving or can be selflessly (genuinely) kind. Do these two intentions elicit different reciprocal reactions? We propose a conjecture that self-serving but generous actions diminish the positively reciprocal response, compared to selfless generous actions. We classify actions that increase a recipient’s maximum payoff, but by less than the giver’s maximum payoff, as being self-serving generous actions, while classifying actions that increase a recipient’s maximum payoff by more than the giver’s as selfless generous actions. We hypothesize that selfless generous actions are considered more generous than self-serving generous actions, and that self-serving generous actions will therefore result in a diminished reciprocal response. We test this conjecture using two novel experimental designs. We find some evidence that subjects perceive self-serving generous actions as being less generous than selfless generous actions, but no empirical support for our conjecture on the diminished reciprocal response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Do you care whether a person is genuinely (selflessly) kind to you or whether he just pretends to be so he could reap future benefits? Does your response to his kind action depend on whether his behavior is potentially strategic (self-serving)? There are many everyday situations where the distinction between genuine or strategic intent plays a crucial role in determining the intensity of behavioral response. Consider the following scenario. You are at a restaurant in a country with a tipping culture and the waiter is providing an extraordinary service. You realize that his kindness might be disingenuous and that he might be pretending to be nice in order to extract a higher tip. How do you tip him? Do you care about the possible intentions behind his action, which while being beneficial to you, was potentially more beneficial to him? Do you then elect to not reward him with a higher tip or do you tip well, in excess of what you normally tip, because you had a pleasant dining experience thanks to his service?

Previous research provides vast evidence that many economic transactions are governed by reciprocity (see Fehr and Gächter 2000; Camerer 2003; Sobel 2005; Fehr and Schmidt 2006; Chaudhuri 2008 for surveys). Kind and unkind intentions behind actions have been identified as an important driving factor of positively (Cox 2004; Cox et al. 2008b; Falk et al. 2008) and negatively reciprocal behavior (Blount 1995; Offerman 2002). Acts of commission, which actively impose kindness or harm, are found to reveal intent to a greater degree and therefore lead to a stronger reciprocal response than acts of omission, which represent failures to act kindly or to prevent harm (Cox et al. 2017). However, not much is known about the intensity of reciprocal responses to the precise nature of those intentions, for example when the level of kindness (or conversely unkindness) increases from ‘kind’ to ‘kinder’. From this perspective, most previous studies could be described as having a ‘binary format’ in that they consider reciprocal responses to kind actions versus actions with neutral or no intentions, or pitch kind actions against unkind ones. Our research takes a step towards the ‘continuous format’ as we keep the underlying actions kind, but vary intentions in a way suggested by the above example with the waiter who is being strategically kind.

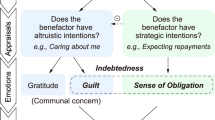

As reciprocity is particularly sensitive to perceived intentions, distinguishing between genuine and strategic intentions is central for understanding of the origins of reciprocal behavior. In this paper we therefore formally develop a conjecture that a self-serving generous action (a specific type of kind behavior that is strategic or fortuitously beneficial to the decision-maker) leads to a weaker positively reciprocal response than a selfless generous action. To pin down the terminology, in the spirit of the Revealed Altruism theory by Cox et al. (2008a) we define self-serving generosity as a giver’s (henceforth, First Mover or FM) action that directly benefits the recipient (henceforth, Second Mover or SM) by increasing her maximum payoff, while also benefiting the FM by increasing his own maximum payoff by more than that of the SM. Similarly, if the action results in a smaller increase (or a decrease) in the FM’s maximum payoff, we classify this as selfless generosity. To investigate reciprocal preferences, we focus on how the SM reacts after a FM chooses either a self-serving or selfless action. Importantly, we keep the underlying FM’s action otherwise equally generous in both cases. This gives us a clean test of the strength of reciprocal responses to actions that are selfless and self-serving.

We experimentally test our conjecture in two novel designs that allow us to vary the precise nature of intentions (self-serving or selfless) in a way pinned down by the underlying theory to study the ‘primitive’ of reciprocity (i.e. the kinder you are to me, the more I am inclined to be kind back). We find some evidence that subjects perceive self-serving generous actions as being less generous than selfless generous actions, which would imply a different reciprocal response from the above basic (naïve) interpretation of reciprocity. Despite that, we find no support for our conjecture on the diminished reciprocal response. Our results have important theoretical implications as they suggest that considerations for self-serving generosity can largely be ignored in models of reciprocal behavior.

2 Relationship to the literature

Economics experiments demonstrate that if kind or unkind intentions can be attributed to actions, the reciprocal response tends to change compared to a situation where no intentions can be inferred from the same actions (e.g. Charness 2004; Gneezy et al. 2000; Kritikos and Bolle 2004). The experimental designs studying the role of intentions thus allow for their presence in one condition and remove them in the control condition by either implementing the choice of the decision-maker exogenously by the experimenter (e.g. Cox 2004), using a randomizing device (e.g., Cox and Deck 2005), or by forcing a particular choice through limiting the choice set to one alternative (e.g. McCabe et al. 2003). Such designs, however, do not permit conclusions regarding the intensity of reciprocal responses based on the different underlying types of intentions that imply varying levels of kindness.

Bruni et al. (2009) go one step further than the earlier papers and vary the nature of intentions (rather than completely removing them), by either informing or not informing the FM who has an opportunity to act in a generous way that the SM can reciprocate. They find that the SMs respond to the possible strategic motivation behind FMs’ generosity and reward them more when extrinsic motives can be ruled out. In contrast to Bruni et al., our design varies the nature of intentions by changing how much the FM stands to gain relative to the SM, making the generosity selfless or self-serving, all while keeping both parties fully informed about the feasible final allocations. Such a distinction is not possible in the Bruni et al. design as the FM and SM’s maximum payoffs are kept constant in their informed and uninformed treatments, meaning they are not different by the ‘self-servingness’ of their FM’s generous actions.

Additionally, our design contrasts with Bruni et al., in that we vary the level of potential strategic motivation, rather than ruling it out entirely. A FM that makes increasingly self-serving (selfless) but generous actions is increasingly more (less) likely to be taking that action for strategic reasons.Footnote 1 From this overall perspective, the novelty of our approach to studying reciprocal behavior comes from varying the nature of intentions by means of how much one person stands to gain relative to another without manipulating the informational content. The channel through which the nature of intentions is varied could be important for the reciprocal response. By varying intentions in terms of observable outcomes, there is less uncertainty about the FM’s decision; the FM knowingly took an action fully understanding the consequences. Changing the informational content as in Bruni et al. is intuitive from a qualitative standpoint, but hard to pin down in terms of quantitative theory, which is an advantage of our approach.

What intuition do existing models of reciprocity provide regarding the importance of self-serving intentions for reciprocal behavior? Distributional preference theories (e.g. Fehr and Schmidt 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels 2000) describe preferences over the final distributions of payoffs, with no considerations for how surplus is generated. Motivations behind actions, such as self-serving generosity, are not considered when decision-makers make their consequential choices; therefore such models do not shed any light on our research question.

Belief-dependent models of reciprocity by Rabin (1993), Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger (2004), or Falk and Fischbacher (2006) incorporate intentions through the SM’s beliefs about the kindness of the FM. For illustration, consider Falk and Fischbacher’s (2006) model that defines a kindness term, which is then used to determine the extent of reciprocal response. The kindness term consists of an intention factor and an outcome factor. The intention factor represents how intentional a FM is being in making a decision, while the outcome factor is the difference between the expected payoffs of the FM and SM. This outcome factor is calculated given the SM’s first-order beliefs about the other’s actions, and their second-order beliefs about the FM’s beliefs about the SM’s own actions. If the kindness factor is positive, the action is considered kind, and if the kindness factor is negative, the action is considered unkind. SMs will want to reward kind actions and punish unkind actions, depending on how reciprocal they are. Actions that meet our definition of self-serving generosity could be considered unkind, as the outcome term is negative if we assume that a SM believes the FM expects to receive more than the SM. Falk and Fischbacher’s model can therefore predict that SMs will respond positively to selfless generous actions and negatively (or less positively) to self-serving generous actions, meaning we should observe a difference in the reciprocal response of the two types of generous actions, assuming fixed beliefs. Nonetheless, whether an action is considered self-serving or not depends entirely on the SM’s beliefs. While in principle it is possible to influence beliefs in experiments (e.g. through framing), in the given scenario they remain outside of our control. Another issue is that the above discussed equilibrium models are complex and have multiple equilibria in higher order beliefs (i.e. beliefs about other’s beliefs), making them intractable in many applications (see Cox et al. 2007 for a more detailed discussion). Akin to the reason expressed nicely in Charness and Dufwenberg (2006), sec. 5.1, pp. 1591–1592, our goal is to test the implication that self-serving actions have for reciprocity, not whether we observe equilibrium play in a one-shot setting and whether subjects form correct beliefs in the presence of self-serving and selfless actions. All of the above makes testing our conjecture troublesome in a belief-dependent framework.Footnote 2

An appropriate theory of reciprocity to embed our explorations in would either have, or allow for introducing, considerations for self-serving motivations, and provide us with clear and testable hypotheses on observables. Such a theory, not dependent on beliefs, is that of Revealed Altruism (Cox et al. 2008a, henceforth CFS). In this theory CFS posit that an action that is more generous than another is met with a more (conditionally) altruistic response. CFS define an action from a FM being ‘more generous than’ (MGT) another to the SM if it meets two conditions. The first condition is that between any two actions, the one that offers the higher SM maximum potential income induces higher generosity. The second requirement is that the increase of the FM’s maximum potential income does not exceed the increase in the SM’s maximum potential income. In other words, the action cannot be self-serving. As the feasible maximum potential incomes of an opportunity set are properly defined, generosity in this theory is determined in an observable and unambiguous way. This is unlike in psychological games that work with individual’s beliefs that are not directly observable, are of a high order, and elicitation of which can be problematic, due to belief elicitation affecting behavior (or vice versa) (e.g. Gaechter and Renner 2010). We therefore use Revealed Altruism as our framework for answering our research question. Revealed Altruism, however, makes no explicit predictions about the reciprocal response to self-serving but generous actions. Rather, it states that actions cannot be self-serving, meaning self-serving generosity is outside the scope of the theory. We therefore expand the Revealed Altruism theory by positing that self-serving actions will elicit a diminished reciprocal response than selfless actions.

Using the maximum payoff in our definition of self-serving generosity follows from Revealed Altruism. The FM’s maximum payoff may seem like an unintuitive choice for considering the FM’s intentions, as the SM is unlikely to desire an allocation that assigns all available surplus to the FM, which leaves nothing to the SM. In situations where allocations near the FM’s maximum payoff are considered unlikely, self-serving and selfless generosity (under the current definition) might be indistinguishable from one another and in such cases one might consider an alternative definition based around the minimum payoffs of the pair, or some other reference payoff instead. Another suggestion could be what the FM believes he will receive back, however, that returns to the issue of (potentially problematic) beliefs. In defense of the maximum payoff, it is plausible that there is correlation between the maximum payoff and the SM’s second order belief, the operative belief that the SM would be using to assess the intentions of the FM. If the maximum payoff the FM can receive increases, it is not unreasonable to propose that the FM expects to receive more back. Therefore, the FM’s maximum payoff becomes a proxy for the SM’s second-order beliefs about the FM’s actions, with the main added advantage of being directly observable.Footnote 3 Ultimately, we retain the use of maximum payoffs in our definition while keeping the above issues in mind.

CFS provide some support for their second condition, using data from Andreoni et al. (2003) Carrot and Stick game. In the Carrot and Stick game, the FM can split $2.40 between himself and the SM, with a minimum of 40 cents being sent to the SM. The game has three variants, the Carrot Game, in which the SM can spend 1 cent to reward the FM by 5 cents, the Stick Game, in which the SM can spend 1 cent to punish the FM by 5 cents, and the Carrot and Stick Game, in which the SM can either reward or punish the FM at the rates previously described.Footnote 4 If we compare the Stick variant to the Carrot and Stick variant, the same FM split decision differ in their MGT ordering according to the second condition. This is because SMs cannot reward FMs in the Stick variant, making generosity selfless, compared to the potentially self-serving generosity in the Carrot and Stick variant. While CFS do report statistical evidence in support of our conjecture, this is not sufficient to answer our research question. The SM’s action sets change between only being able to punish (or do nothing), to being able to punish and reward (or do nothing). Such a change could influence behavior for reasons other than self-serving generosity. For example consider the observed individual behavior between Dictator games where FMs could ‘give’ money to the SM, or ‘take’ money from the SM (e.g. Bardsley 2008; Cappelen et al. 2013; Cox et al. 2016), where the addition of the option to take reversed FM preferences from giving to taking. Such an effect potentially confounds these Carrot and Stick results on self-serving generosity, which motivates our experimental design as a cleaner, specific, test of whether self-serving generosity diminishes the reciprocal response compared to selfless generosity.

3 Theoretical framework

3.1 Revealed Altruism theory

The following section provides a comprehensive overview of Revealed Altruism. CFS develop a model of reciprocity in the spirit of neoclassical economic theory. Suppose there are two players, ‘me’, and ‘you’.Footnote 5 Let ‘my’ income be denoted m and ‘your’ income be denoted y. ‘My’ preferences over m and y are smooth, convex and strictly increasing in m. Well-behaved preference can be represented by a general utility function denoted \(u\left( {m,y} \right)\), which has a positive partial derivative with respect to m, or \(\frac{{\partial u\left( {m,y} \right)}}{\partial m} > 0\), meaning ‘my’ utility is increasing in m. The partial derivative with respect to y,\(\frac{{\partial u\left( {m,y} \right)}}{\partial y}\), could be zero everywhere if ‘I’ am selfish, or could be positive or negative depending on ‘my’ benevolence or malevolence, respectively. The marginal rate of substitution of m for y, is represented in Eq. 1.

Equation 1 is undefined for selfish preferences (as \(\frac{{\partial u\left( {m,y} \right)}}{\partial y} = 0\)), and swings from + ∞ to − ∞ as preferences pass from slight benevolence to slight malevolence, so it is convenient to instead use willingness to pay, as presented in Eq. 2.

The willingness to pay, w, represents the amount of m ‘I’ am willing to give up in order to increase y by one unit. Note that w is intrinsic, i.e., it is invariant to monotonic transformations of u(.). A more altruistic than (MAT) preference ordering is defined as follows. Let A and B be two preference orderings over m and y. A is MAT B if, for a given domain D, \(w_{A} \left( {m,y} \right) \ge w_{B} \left( {m,y} \right), \forall \left( {m,y} \right) \in D\), or in other words, ‘my’ willingness to pay in A either exceeds or is equal to ‘my’ willingness to pay in B, at any allocation (m,y) from D.

‘Your’ action creates an opportunity set, F. Let \(y_{F}^{*}\) be ‘your’ maximum feasible income in F, and similarly let \(m_{F}^{*}\) be ‘my’ maximum feasible income in F. An action that creates an opportunity set G is considered MGT an action that creates an opportunity set F if it meets the following two conditions presented in Eqs. 3 and 4:

In other words, Condition A states that G is MGT F, if G provides ‘me’ with at least as much if not more potential income than F. Condition B states the set G cannot increase ‘your’ potential income by more than ‘mine’, compared to F.

The Revealed Altruism model includes two axioms, Axiom R and Axiom S. Axiom R refers to reciprocity, the concept of rewarding (or punishing) good (bad) actions. More formally, Axiom R states:

Let the first mover choose the actual opportunity set for the second mover from the collection C. If F,G \(\in\) C and G is MGT F, then \(A_{G}\) is MAT \(A_{F}\).Footnote 6

(Cox et al. 2008, p. 40).

Therefore, if the opportunity set following your action is MGT of an alternative feasible opportunity set, then it will be met with a MAT response. In other words, if ‘your’ action increases ‘my’ potential earnings without increasing ‘yours’ by more, then my choice will be more generous. Axiom S, which however is not relevant for our research question, states that acts of commission elicit stronger reciprocal response than acts of omission.

3.2 Conjecture and extension of Revealed Altruism

It is with the preceding framework in mind that we present our conjectures on self-serving generosity. Condition B (Eq. 4) is related to the proposed concept of self-serving generosity. It effectively states that two opportunity sets cannot be MGT ordered if a generous action is self-serving. Condition B could be interpreted as a domain in which, when it is satisfied, predictions from the Revealed Altruism theory are defined. Outside of this domain the CFS version of the theory does not offer predictions. We next posit how Condition B affects the MGT ordering.

If the inequality of Condition B is not satisfied, this could affect the MGT ordering. We define an action that satisfies Condition B as a selfless action. A selfless action potentially benefits the recipient by more (or at least as much) as the proposer, and it is unambiguous that the action is generous. We define an action that violates Condition B as self-serving. In the case of a self-serving action, the FM potentially stands to gain more than the SM, so the FM’s kind intentions of any generous but self-serving action are not clearly revealed. We propose that if both actions are equal in MGT ordering according to Condition A (i.e. they both make the recipient equally better off), a selfless action is considered MGT a self-serving action. If a MGT action elicits a MAT response, we therefore posit that a selfless action will elicit a MAT response than a self-serving action.

Figure 1 presents our conjecture graphically in terms of opportunity sets over my income (m), and your income (y). Consider the status quo opportunity set F, where \(y_{F}^{*} = m_{G}^{*} = 5\), and three alternative opportunity sets G, H, and I, where \(m^{*} = 6\), but \(y^{*}\) varies. Opportunity sets G and H satisfy both Condition A and Condition B and are thus MGT F. Opportunity set I satisfies by Condition A but not Condition B. Note, we cannot specify an MGT ordering of G, H, and I by Condition A alone, instead we refer to Condition B. We propose that G is MGT F, H, and I; H is MGT F and I; and I is MGT F.

4 Experiment 1

In general, it is quite difficult to acquire data on reciprocal behavior from everyday situations, due to the private nature of many interactions. Even if such interactions were observable, it would be difficult to infer intent, as there are numerous other considerations at play. For example, interaction between two parties is often subject to repetition, meaning motivations may include reputation-building. Even in one-shot interactions, there are motivations such as social norms or social pressure that could confound any attempt to investigate the impact of self-serving actions on reciprocity. A solution is to conduct a one-shot interaction in controlled laboratory conditions. The non-repeated nature of the interaction strips away some motivations not related to the research question, and a sufficiently calibrated design removes any remaining confounds, leaving only the motivations in question to be studied.

4.1 Design

To explore our conjecture, we employ the Lost Wallet Game, henceforth LWG (Dufwenberg and Gneezy 2000). In the LWG, presented in Fig. 2, a First Mover can choose either IN or OUT. If the FM chooses OUT, he receives his outside option x, and the Second Mover receives nothing. If the FM chooses IN, then $20 is made available for the SM to split between the pair with y going to the FM and 20-y to the SM.

Our objective is to test whether a violation of Condition B affects the reciprocal response, and in order to do so, we hold all other factors that could affect the MGT ordering constant, mainly Condition A. In the LWG Condition A is constant regardless of x, as the SM always stands to gain up to $20. We can make changes to Condition B by varying x, which will vary how beneficial it is to the FM to choose IN, and subsequently how selfless or self-serving choosing IN is.

As the FM stands to gain up to 20-x, for all positive x, choosing IN is selfless, as the FM’s maximum potential income will always be less than the SM’s (who always stands to gain up to 20). In order to make choosing IN self-serving, we implement a negative x, which makes our implementation of the LWG novel and unique. We therefore propose two treatments, a Selfless treatment where x = 4, and a Self-Serving treatment where x = − 2.Footnote 7 Intuitively, a FM is being selfless when he gives up $4 to choose IN, compared to when he gains $2 by choosing IN. By the theory, in the x = − 2 treatment, choosing IN is self-serving, as the FM stands to gain up to $22, whereas the SM stands to gain only up to $20. The negative outside option is implemented by a reduction in the subject’s show-up fee.

Additionally, in a questionnaire administered at the end of the experiment we elicit non-incentivized beliefs about generosity and on other subject’s actions. We elicit subject perceptions about generosity using a 5-point scale (Likert 1932), where 1 is not generous and 5 is very generous. We ask both the FMs and SMs whether they considered the FM’s choice of IN to be generous. This manipulation check allows us to shed further light on the potential MGT ordering.

4.2 Hypotheses

The crux of our experiment, testing whether potential self-serving considerations behind generous behavior are important to reciprocity, comes down to the following three main hypotheses. For the ease of explanation, we present the hypotheses (and results) in parallel to the Revealed Altruism theory, i.e. we first establish support for whether the MGT ordering holds and only then focus on the MAT response, which is directly related to our research question.

We conjecture that choosing IN in the Selfless x = 4 treatment is MGT to choosing IN in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment, as the two actions are of equivalent MGT ordering by Condition A, but vary by Condition B. Firstly, if an action has a higher MGT ordering, then we expect FMs and SMs to perceive that action as being more generous.Footnote 8

H1

FMs and SMs will perceive choosing IN as being more generous in the Selfless treatment x = 4 than in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment.

Secondly, since choosing IN is self-serving for the FM when x = − 2, and selfless for the FM when x = 4, we expect that more FMs will choose IN when doing so is self-serving:

H2

FMs will choose IN more often in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment than in the Selfless x = 4 treatment.

Finally, in the theory of Revealed Altruism a MGT action elicits a MAT response. In our design SMs should therefore allocate a larger proportion of the $20 to the FM (y) if choosing IN is indeed MGT.

H3

SMs will choose a higher y in the Selfless x = 4 treatment than in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment.

4.3 Procedures

The experiment was run under the single blind social distance protocol in the New Zealand Experiment Economics Laboratory at the University of Canterbury. 154 student subjects, recruited using the online recruitment system ORSEE (Greiner 2015), participated, with 74 subjects (= 37 observations) in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment, and 80 subjects (= 40 observations) in the Selfless x = 4 treatment.Footnote 9 Subjects participated in one treatment only, making this design between-subjects. Subjects were on average paid NZ$ 18.78, with all sessions lasting approximately 50 min.Footnote 10 Subjects made their decisions in a program implemented in z-Tree (Fischbacher 2007). The $− 2 outside option was enforced by reducing the FMs’ $5 show-up fee to $3, so instead of receiving $5 in addition to their experiment earnings, they would receive $3. The SM’s decision was elicited using the strategy method (Selten 1967; Brandts and Charness 2011), i.e. if a FM chose IN, then the division of the $20 the SM decided on would actually be enacted. After all subjects had completed their decisions, they were informed they were to receive $5 for filling out a questionnaire in addition to their show up fee. This previously unannounced payment for filling out the questionnaire was to increase subjects’ effort in the questionnaire, which contained the generosity perception elicitation as the first question.

5 Results

Table 1 reports summary statistics and tests for both FMs and SMs. Recall that both FMs and SMs were asked on a 5-point scale how generous they thought choosing IN was (with 5 being very generous, and 1 being not generous). H1 predicts that choosing IN when doing so is selfless will be considered more generous than choosing IN when it is self-serving. FMs reported an average generosity perception of 3.83 in the Selfless x = 4 treatment, and 3.14 in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment. The averages are in the direction posited by H1, and the difference is statistically significant with the Mann–Whitney 2-sided test reporting p = .029.Footnote 11

SMs reported an average generosity perception of 3.30 in the Selfless x = 4 treatment, and 2.73 in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment. The averages are in the direction posited, and are statistically significant at the 10% level, with the Mann–Whitney test reporting p = .064.Footnote 12 Our non-saliently elicited data thus provides evidence for H1, that both FMs and SMs consider choosing IN as being more generous when x = 4 than when x = − 2, in line with our conjecture. An additional incentivized generosity perception elicitation was performed with a separate group of subjects, the full details and analysis of which are presented in Appendix C of the ESM. This additional session provides further evidence for H1, with \(p = .08\).

Choosing IN in the current experiment was designed to be self-serving for the FM when x = − 2, and selfless for the FM when x = 4. H2 therefore predicted that more FMs will choose IN when doing so is self-serving than when it is selfless. Evidence presented in Panel A of Table 1 supports H2 as 95% of FMs chose IN in the x = − 2 treatment and 78% of FMs chose IN in the x = 4 treatment. This difference is statistically significant according to the Fisher’s exact test (p = .049).

Our design thus passes an important manipulation check: Both FMs and SMs consider choosing IN to be more generous in the Selfless x = 4 treatment than in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment. FMs additionally choose IN more often when doing so is self-serving.

We now move onto SM behavior. If SMs consider IN being of differing levels of generosity, i.e. H1 is supported, then our reciprocity conjecture implies that SMs will subsequently be inclined to allocate more to the FM when IN is considered more generous, as predicted by H3.

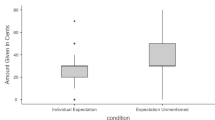

However, Table 1 reports no evidence in favor of H3. On average, SMs allocate 5.42 to FMs in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment, and 5.45 in the Selfless x = 4 treatment, and there is no statistically significant difference (p = .992). We therefore reject H3 that SMs choose a higher y in the Selfless x = 4 treatment than in the Self-Serving x = − 2 treatment (Fig. 3).

Additional regression and demographic analysis is presented in Appendix D of the ESM.

5.1 Discussion

Taken together, generosity perceptions in both Experiment 1 and the additional incentivized generosity perceptions reported in the appendix point out that choosing IN was perceived to be less generous when x = − 2 than when x = 4, as suggested by our accepted definitions of self-serving and selfless generosity, confirming that the Lost Wallet Game is indeed an appropriate environment to test our conjecture. H1 supports our conjecture, based on a proposed revision of MGT ordering, but H3 does not support our MGT revision, as it has not borne out that an MGT action has elicited a MAT response, an important part of Revealed Altruism. Our finding of evidence in support of H1 but finding a lack of support for H3 is puzzling. SMs consider FMs to be less generous when they choose IN in our self-serving treatment, however, this elicits no difference in reciprocal response towards FMs.

However, the empirical evidence of the LWG has shown that typically varying x does not have an effect on y (Dufwenberg and Gneezy 2000; Servátka and Vadovič 2009; Cox et al. 2010; and also the no negotiations treatments in Dufwenberg et al. 2017), which seems to indicate a lack of positive reciprocity in this game.Footnote 13 WIn light of this, Experiment 1 was perhaps a too conservative test of our conjecture. Our findings may be an artefact of the LWG itself. Cox et al. (2010) hypothesize that the observed lack of positive reciprocity could be driven by the opportunity set of the SM being invariant to the size of the foregone outside option of the FM, a notable difference with the Investment Game (Berg et al. 1995) where each dollar sent by the FM enlarges the SM opportunity set and where positive reciprocity is one of the driving factors of SM behavior (Cox 2004). We therefore find it prudent to check the robustness of our findings in a different experimental design.

5.2 Experiment 2

5.2.1 Design

For Experiment 2 we use the Investment Game (Berg et al. 1995). Unlike the Lost Wallet Game, Investment Game experiments have found SM behavior to be responsive to choices made by the FM (Johnson and Mislin 2011), and will thus present a less conservative test of our conjecture. Recall that in order to test whether self-serving generosity leads to a weaker reciprocal response, we must hold Condition A constant while varying Condition B. One way of achieving this is in the Investment Game is to use different exchange rates on amounts kept by the SM, and amounts returned to the FM by the SM. To implement such exchange rates we adapt the procedures used by Andreoni and Miller (2002) for use in the Investment Game. Figure 4 presents our design.

The FM starts with ten tokens, and can choose IN or OUT. If the FM chooses OUT, then he earns ten points. If the FM chooses IN, then the ten tokens are made available for the SM to split. In all treatments, tokens that the SM holds for herself earn her three points per token, which holds Condition A constant across treatments.Footnote 14 Tokens that the SM decides to send to the FM earn the FM s points, depending on treatment. SMs can send any integer amount of tokens from 0 to 10. By varying s we control how selfless or self-serving a FM choosing IN is. Note that the ‘channel’ in which we alter Condition B is different from Experiment 1, where the outside option was varied. The ‘channel’ is altered as a robustness check of Experiment 1, to avoid the potential artefactual issues of the LWG described previously. Choosing IN when s = 4 is neither selfless nor self-serving by our definition, as FMs have a maximum potential gain of 30 (they forgo 10 points to choose IN), which is the same as the SM’s maximum potential gain of 30 (which is invariant in s). Values of s smaller than 4 result in the choice of IN being selfless, and values larger than 4 result in the choice of IN being self-serving. We fix our Selfless treatment as s = 2, and our Self-Serving treatment as s = 6, to ensure sufficient and equal distance from our what would be ‘neutral’ s = 4.

Andreoni and Miller (2002) report that in their Dictator Game, a non-trivial number of subjects exhibit a desire to maximize surplus. If SMs behave similarly in our experiment, then they will want to allocate more tokens to FMs when s = 6, as this maximizes surplus. This is a potential confound, and acts in the opposite direction of our hypothesis. In order to control for this, we implement a third Random treatment where there is a 50% chance s = 2 eventuates, and a 50% chance s = 6 eventuates. SMs are familiar with the nature of the FM’s decision. They are also informed which outcome has eventuated prior to their own decision, whereas FMs are not. The expected value of s is 4, so a FM choosing IN is being neither selfless nor self-serving in the Random treatment.Footnote 15 Taking advantage of this fact, and comparing SM reaction to selfless or self-serving FM actions (where s is fixed prior to the FM decision to be 2 and 6, respectively) to the corresponding neutral FM actions, we can separate out the confound of surplus maximization, as well as individually identify a SMs response to a selfless or self-serving FM action. Table 2 presents this identification of potential effects, with isolated effects in italic.

5.3 Hypotheses

Our conjecture remains the same as in Experiment 1, while our hypotheses change to fit the design of Experiment 2. Both FMs and SMs should perceive our Selfless s = 2 treatment to be more generous than both our neutral Random treatment and Self-Serving s = 6 treatment. FMs and SMs should also consider our neutral Random treatment to be more generous than our Self-Serving s = 6 treatment.

H4

FMs and SMs will perceive choosing IN as being more generous:

-

in the Selfless s = 2 treatment than in the Random treatment,

-

in the Random treatment than in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment.

Just as in Experiment 1, we expect the FMs’ behavior to correspond to how self-serving or selfless choosing IN is.

H5

FMs will choose IN more often:

-

in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment than in the Random treatment,

-

in the Random treatment than in the Selfless s = 2 treatment,

-

in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment than in the Selfless s = 2 treatment.

In terms of SM behavior, we focus our analysis on the isolated effects presented in Table 2. For the selflessness effect, we predict that SMs will allocate more to the FM in the Selfless s = 2 treatment than when s = 2 eventuates in the Random treatment. Such a reaction would be triggered by the FM being selfless by choosing IN when s is fixed to be 2, as opposed to having neither selfless nor self-serving intentions by choosing IN in the Random treatment. According to our conjecture, SMs may want to reward selflessly generous FMs more than neutrally generous FMs.

An important consideration in our design is that because of the different token redemption rates (which determine the total number of points) between our treatments, the number of tokens allocated to the FM might vary because of the different redemption rate, rather than due to a change in reciprocity. Therefore, rather than stating our hypotheses using the number of tokens allocated to the FM, we formulate them in terms of the percentage of the total surplus.

H6

SMs will allocate more surplus to the FM in the Selfless s = 2 treatment than when s = 2 eventuates in the Random treatment.

For the self-serving effect, we expect that SMs will allocate more of the surplus to the FM in the Random treatment where s = 6 eventuates than in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment, as SMs may wish to reward neutrally generous FMs more than self-serving generous FMs.

H7

SMs will allocate more surplus to the FM when s = 6 eventuates in the Random treatment than in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment.

Finally, for the surplus maximization effect, we compare the two possible states of nature in the Random Treatment. We expect that SMs will allocate more of the surplus to the FM when s = 6 eventuates, as it maximizes surplus, and it is relatively cheaper to do so.

H8

In the Random treatment SMs will allocate more surplus to the FM when s = 6 eventuates than when s = 2 eventuates.

5.4 Procedures

Experiment 2 was also run in the New Zealand Experiment Economics Laboratory at the University of Canterbury. 222 subjects participated in total, with 64 subjects (= 32 observations) in the Selfless s = 2 treatment, 64 subjects (= 32 observations) in the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment, and 94 subjects (= 47 observations) in the Random treatment.Footnote 16 None of the Experiment 2 subjects participated in Experiment 1. Subjects were paid on average NZ$ 17.69, with all sessions lasting approximately 50 min. The procedures used in Experiment 2 replicate those of Experiment 1. In the Random treatment, FMs were not informed of the realization of s when making their decision. SMs were informed of the realization of s before making their decision, and only made a decision for that realization of s. If a FM chose IN, then the proposed division of tokens by the SM would be implemented. After all subjects had completed their decisions, they were informed they were to receive $5 for filling out a questionnaire. As in Experiment 1, the additional payment was to increase subject’s effort in the questionnaire, of which, the generosity perception elicitation was presented first. After subjects had completed the questionnaires, they were asked to come one by one to the payout room to receive their earnings in private, where the points earned in the experiment were exchanged at the preannounced rate of $.60 NZD per point.

5.5 Results

Table 3 reports summary statistics and statistical tests on both FM and SM behavior in Experiment 2. Because of our focus on isolating individual effects, we provide pairwise comparisons and statistical tests.

We start by exploring subject’s non-incentivized generosity perceptions. H4 predicts that choosing IN in the Selfless treatment will be perceived to be more generous than in the Random treatment, that choosing IN in the Selfless treatment will be perceived to be more generous than in the Self-Serving treatment, and that choosing IN will be perceived to be more generous in the Random treatment than in the Self-Serving treatment.

FMs reported an average generosity perception of 3.94 in the Selfless treatment, 3.70 in the Random treatment, and 3.59 in the Self-Serving treatment. While the averages are in the hypothesized directions, there are no statistically significant differences between any of our treatments. We find no evidence in support of H4 from FM behavior.

SMs reported an average generosity perception of 4.03 in the Selfless treatment, 3.72 in the Random treatment, and 3.56 in the Self-Serving treatment. As with FMs, the averages are in the hypothesized direction, but unlike FMs, there exists a weak statistical difference between the Selfless and Self-Serving treatments, with the Mann–Whitney test reporting p = .082.Footnote 17 Therefore, there is some weak evidence in support of a part of H4, which is the most relevant comparison from the perspective of our research question. Regarding our findings on the differences in generosity perceptions being weaker in Experiment 2 than in Experiment 1, we note that it may be due to the increased complexity of Experiment 2, or the calibration providing a smaller magnitude of separation in generosity perception. The additional, incentivized generosity perception elicitation reported in Appendix C of ESM finds no evidence for H4, with no statistical difference in generosity perception.

We continue the analysis with the FM behavior. 44% of FMs chose IN in the Selfless treatment, 81% in the Random treatment, and 66% in the Self-Serving treatment. The Fisher’s exact test only reports a statistically significant difference in FM behavior between the Random and Selfless treatment (p = .001) with the difference between the Selfless and Self-Serving treatment being marginally insignificant (p = .131). We therefore find some evidence in support of a part of H5.

As mentioned earlier, when analyzing SM decisions, it is helpful to report the percentage of the surplus allocated to the FM instead of the number of tokens for the comparison between treatments with differing token redemption rates. For comparability between all SM results, we report this percentage for all SM token allocations. We now test our hypotheses on SM behavior, starting with isolating the ‘selflessness effect’. Hypothesis H6 predicts that SMs will allocate more of the surplus to the FM in the Selfless treatment than in the neutral Random treatment, where the same token redemption rate s = 2 eventuates. The intuition behind the hypothesis is that SMs may want to more highly reward those FMs who exhibit selfless generosity, than those FMs who exhibit neutral generosity (Figs. 5, 6).

In the Selfless s = 2 treatment, SMs on average allocated 27.0% of the surplus to FMs, while in the Random treatment where s = 2 eventuated SMs on average allocated 20.7%. The averages are in the hypothesized direction, however, this result is not statistically significant (p = .245). Therefore, we find no evidence in support of H6.

In a similar line of reasoning to the selflessness effect, we hypothesize that SMs will respond by diminishing their reciprocity due to the ‘self-servingness’ effect as they may not want to reward FMs whose intentions could be self-serving. Hypothesis H7, capturing this effect, predicts that SMs will allocate more surplus in the neutral Random treatment where s = 6 has eventuated by chance compared to the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment.

In the Self-Serving s = 6 treatment, SMs on average allocated 40.4% of the surplus to FMs, while in the Random treatment where s = 6 eventuated SMs on average allocated 50.1%. The averages are in the hypothesized direction, however, the difference is marginally insignificant (p = .142). Therefore, we find no evidence in support of H7.

Our last hypothesis, H8, explores the need for our Random treatment to control for the possibility that SMs may wish to maximize surplus by allocating more to the FM when the redemption rate is higher. To do this, we compare the SM response to s = 2 and s = 6 within our Random treatment. As the FM’s intentions are constant in the Random treatment, we can focus on the effect of the differing s.

When s = 6 eventuated in the Random treatment, SMs allocated on average 50.1% of the surplus to FMs, whereas SMs allocated on average 20.7% when s = 2 eventuated. This result is statistically significant (p = .0001), and provides strong evidence for H8. This finding justifies the need for our Random treatment to control for surplus maximization effects. If this effect was not controlled for, a confounded test of a combined selfless and self-serving effect, which directly compares SM behavior between our Selfless and Self-Serving treatment, would report a statistically significant difference (p = .013). To use this as evidence of self-serving generosity affecting reciprocity would be erroneous due to the presence of the surplus maximization effect. Alternatively, to separate out selfless and self-serving effects, one could introduce a treatment where s = 4 without a random element. Such an approach would also be erroneous due to the presence of the surplus maximization effect.

As with Experiment 1, regression and demographic analysis is presented in Appendix D of the ESM.

5.6 Discussion

While the design of Experiment 2 employs the same definitions and therefore ex ante satisfies the theoretical requirements for testing our conjecture, we find only a weak statistical difference in generosity perceptions between the Selfless and Self-Serving treatments in the actual experiment and no statistical differences in the robustness check. As hypothesized earlier, the increased complexity of the Investment Game environment or its calibration might make the differences in generosity levels (of choosing IN) less salient in the existing treatments. Importantly, however, the results of Experiment 2 confirm those of Experiment 1 in that self-serving generosity does not lead to weaker reciprocity than selfless generosity. Thus from the statistical point of view this corroborated evidence increases the confidence in our findings compared to a situation if the data were generated in one environment only.

6 Conclusion

Life is full of examples where people pretend to be kind, but do so because their exhibited kindness has the potential to benefit them. Do beneficiaries of such kind actions care about their self-serving nature and take it into account when responding? Our intuition, supported by prior empirical evidence on the importance of intentions, tells us they might care. We set out to study whether self-serving generosity, which is a particular type of kindness, affects reciprocal behavior. The novelty of our approach lies in manipulating the nature of intentions (as opposed to only removing them), which is central to understanding of reciprocal preferences.

Utilizing the framework of Revealed Altruism, we developed a conjecture on how selfless and self-serving generosity impacts reciprocal behavior. We defined actions that satisfied Revealed Altruism’s Condition B to be selfless, and actions that violated Condition B to be self-serving. We proposed that self-serving but generous actions are less generous than selfless actions, and should therefore elicit a diminished reciprocal response. Using novel designs that varied whether an action was selfless or self-serving while holding other generosity considerations constant, we found no difference in reciprocal response to selfless and self-serving (but equally generous) offers. This is despite the fact that subjects generally considered our selfless and self-serving treatments to be of differing levels of generosity. A possible explanation is that SMs give the FMs the ‘benefit of the doubt’, and assume FMs have selfless rather than self-serving intentions when both could be present, a finding akin to Cox and Deck (2006).

Most theories of (positive) reciprocity can generally be condensed down to a ‘primitive’, a desire to reward generous actions. It follows that the desire to reward would increase with how generous the action is; meaning our finding of differences in generosity perception (in particular in Experiment 1) but not reciprocal behavior is puzzling. Our original elicitation of subjects’ generosity perception was non-salient, however, we replicated the differences in generosity perception with an elicitation utilizing a salient proper scoring rule (see Schlag et al. 2015, for a review). Our findings suggest there is more work to be done on the channels through which reciprocity operates, in order to fully understand this important economic phenomenon.

Apart from providing empirical evidence that people do not seem to respond to self-serving intentions, our results have important theoretical implications. In particular, our data suggest that Revealed Altruism might not need the restriction of Condition B in a MGT ordering, as it appears to have no impact on the MAT response and that a ‘MGT light’ ordering (proposed by CFS, p. 36), which only includes Condition A, may be sufficient. Such a refinement of Revealed Altruism would increase the parsimony of the theory, without reducing its descriptive and predictive properties. A SM appears to only consider what a generous action means for her own payoff, and this consideration appears to dominate any ulterior intentions a FM may have. However, we also acknowledge that more research would be required to confidently remove Condition B from Revealed Altruism, such as robustness checks over different sets of parameters and environments (e.g. consider a situation when the FM could gain $1 M while the SM only $1), investigating Condition B’s effects over negative reciprocity, and investigating the potential interaction effects of Conditions A and B.

Notes

As will become clearer in our design the strategic element stems from the fact that the FMs can receive more back than their outside option. This is possible in all our treatments; in our self-serving treatments, more people will be taking the action for strategic reasons as it is more feasible that they will receive back more.

Other shortcomings and limitations of belief-dependent models of reciprocity are discussed in Hinz and Nicklisch (2015) who explore the continuity of the reference value [employed by Rabin (1993) and Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger (2004)] and the continuity of the intention factor (Falk and Fischbacher 2006) in a series of mini-ultimatum games. They find that the distance of the observed offers to the proposed reference value provides a poor measure for their kindness and that a pairwise comparison of offers à la Falk and Fischbacher’s model cannot explain behavior in richer settings.

What definition best approximates self-serving generosity under what circumstances is an interesting empirical question in its own right; however, we leave such explorations for future research.

SMs can spend the entirety of the amount they are sent by the FM, but are limited in not reducing the FM’s final payoff below zero.

The theory is general (N players), however, the two player case is presented for ease of explanation. We present the theory in its original version, where ‘me’ represents the SM and ‘you’ the FM.

\(A_{X}\) is the preference ordering after observing the action that creates opportunity set X, where X \(\in\) C.

In Dufwenberg and Gneezy (2000), x took the values of 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16. In our experiment we chose x = 4 for replication purposes, and x = − 2 as it was the first negative instance counting down in steps of three from x = 4.

A power analysis is presented in Appendix E of the ESM.

Minimum wage in New Zealand was NZ$13.50 per hour at the time of the experiments.

We adopt a conservative approach and report 2-sided tests throughout the paper.

A Mann–Whitney test on pooled data from both FMs and SMs reports p = .007.

See also Woods and Servátka (2016) for evidence of psychological forward induction and the updating of beliefs in the environment of the Lost Wallet Game.

Note the deliberate similarity to the Investment Game, where amounts invested by the FM are typically tripled for the SM to split.

CFS do not mention moves that are determined by chance, so we assume that MGT ordering is determined by the expected value of \(m_{G}^{*}\) and \(y_{G}^{*}\). Such an assumption seems natural and intuitive, and a similar approach is used by Sebald (2010) to extend Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger (2004).

A power analysis is presented in Appendix E of the ESM.

Using pooled data of both FM and SM generosity perceptions, a Mann–Whitney test reports: for H4 p = .073; for H5 p = .035; and for H6 p = .536. Note that such an approach provides support for H5 and mild evidence in support of H4.

References

Andreoni, J., Harbaugh, W., & Vesterlund, L. (2003). The carrot or the stick: Rewards, punishments, and cooperation. American Economic Review, 93(3), 893–902.

Andreoni, J., & Miller, J. (2002). Giving according to GARP: An experimental test of the consistency of preferences for Altruism. Econometrica, 70(2), 737–753.

Bardsley, N. (2008). Dictator game giving: Altruism or artefact? Experimental Economics, 11(2), 122–133.

Berg, J., Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. (1995). Trust, reciprocity, and social history. Games and Economic Behavior, 10, 122–142.

Blount, S. (1995). When social outcomes aren’t fair: The effect of causal attributions on preferences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 63(2), 131–144.

Bolton, G. E., & Ockenfels, A. (2000). ERC: A theory of equity, reciprocity, and competition. American Economic Review, 90(1), 166–193.

Brandts, J., & Charness, G. (2011). The strategy versus the direct-response method: A first survey of experimental comparisons. Experimental Economics, 14, 375–398.

Bruni, L., Corazzini, L., & Stanca, L. (2009). Testing theories of reciprocity: Do motivations matter? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71(2), 233–245.

Camerer, C. F. (2003). Behavioral game theory: Experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cappelen, A. W., Nielsen, U. H., Sørensen, E. Ø., Tungodden, B., & Tyran, J.-R. (2013). Give and take in dictator games. Economic Letters, 118(2), 280–283.

Charness, G. B. (2004). Attribution and reciprocity in an experimental labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(3), 665–688.

Charness, G., & Dufwenberg, M. (2006). Promises and partnership. Econometrica, 74(6), 1579–1601.

Chaudhuri, A. (2008). Experiments in economics: Playing fair with money. London: Routledge.

Cox, J. C. (2004). How to identify trust and reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 46, 260–281.

Cox, J. C., & Deck, C. A. (2005). On the nature of reciprocal motives. Economic Inquiry, 43(3), 623–635.

Cox, J. C., & Deck, C. A. (2006). Assigning intentions when actions are unobservable: The impact of trembling in the trust game. Southern Economic Journal, 73(2), 307–314.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Gjerstad, S. (2007). A tractable model of reciprocity and fairness. Games and Economic Behavior, 59(1), 17–45.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Sadiraj, V. (2008a). Revealed Altruism. Econometrica, 76(1), 31–69.

Cox, J. C., List, J., Price, M., Sadiraj, V., & Samek, A. (2016). Moral costs and rational choice: Theory and experimental evidence. Working paper 2016.

Cox, J. C., Sadiraj, K., & Sadiraj, V. (2008b). Implications of trust, fear, and reciprocity for modelling economic behavior. Experimental Economics, 11(1), 1–24.

Cox, J. C., Servátka, M., & Vadovič, R. (2010). Saliency of outside options in the lost wallet game. Experimental Economics, 13(1), 66–74.

Cox, J. C., Servátka, M., & Vadovič, R. (2017). Status quo effects in fairness games: Reciprocal responses to acts of commission vs. acts of omission. Experimental Economics, 20, 1–18.

Dufwenberg, M., & Gneezy, U. (2000). Measuring beliefs in an experimental lost wallet game. Games and Economic Behavior, 30(2), 163–182.

Dufwenberg, M., & Kirchsteiger, G. (2004). A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 47(2), 268–298.

Dufwenberg, M., Servátka, M., & Vadovič, R. (2017). Honesty and informal agreements. Games and Economic Behavior, 102(2017), 269–285.

Falk, A., Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2008). Testing theories of fairness—Intentions matter. Games and Economic Behavior, 62(1), 287–303.

Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), 293–315.

Fehr, E., & Gächter, S. (2000). Fairness and retaliation: The economics of reciprocity. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3), 159–181.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (2006). The economics of fairness, reciprocity and Altruism—Experimental evidence and new theories. In S. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, Altruism and reciprocity. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Gaechter, S., & Renner, E. (2010). The effects of (incentivized) belief elicitation in public goods experiments. Experimental Economics, 13(3), 364–377.

Gneezy, U., Güth, W., & Verboven, F. (2000). Presents or investments? An experimental analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 21(5), 481–493.

Greiner, B. (2015). Subject pool recruitment procedures: organizing experiments with ORSEE. Journal of the Economic Science Association, 1(1), 114–125.

Hinz, J., & Nicklisch, A. (2015). Reciprocity models revisited: Intention factors and reference value.Hamburg Wiso Working Paper Series 2015/25.

Johnson, N. D., & Mislin, A. A. (2011). Trust games: A meta-analysis. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32, 865–889.

Kritikos, A., & Bolle, F. (2004). Approaching fair behavior: Distributional and reciprocal preferences. Research on Economic Inequality, 11, 149–181.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 5–55.

McCabe, K., Rigdon, M., & Smith, V. (2003). Positive reciprocity and intentions in trust games. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 52, 267–275.

Offerman, T. (2002). Hurting hurts more than helping helps. European Economic Review, 46(8), 1423–1437.

Rabin, M. (1993). Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review, 83(5), 1281–1302.

Schlag, K., Tremewan, J., & van der Weele, J. (2015). A penny for your thoughts: A survey of methods for eliciting beliefs. Experimental Economics, 18(3), 457–490.

Sebald, A. (2010). Attribution and reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 68(1), 339–352.

Selten, R. (1967). Die Strategiemethode zur Erforshung des eingeschränkt rationalen Verhaltens im Rahmen eines Oligopolexperiments. In H. Sauermann (Ed.), Beiträge zur experimentellen Wirtschaftsforschung (pp. 136–168). Tübingen: Mohr.

Servátka, M., & Vadovič, R. (2009). Unequal outside options in the lost wallet game. Economics Bulletin, 29(4), 2870–2883.

Sobel, J. (2005). Interdependent preferences and reciprocity. Journal of Economic Literature, 43, 392–436.e.

Woods, D. (2013). Does self-serving generosity diminish reciprocal behaviour. (M.Com.), University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

Woods, D., & Servátka, M. (2016). Testing psychological forward induction and the updating of beliefs in the lost wallet game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 56, 116–125.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor Lata Gangadharan, Tim Cason, Jeremy Clark, Andreas Nicklisch, Vjollca Sadiraj, Daniel Schunk, Radovan Vadovič, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments, as well as participants of various conferences, workshops, and seminars where this work was presented. This paper is based on Daniel Woods’ Masters thesis written at the University of Canterbury (Woods 2013). Funding was provided by the College of Business and Economics, University of Canterbury and the Macquarie Graduate School of Management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Woods, D., Servátka, M. Nice to you, nicer to me: Does self-serving generosity diminish the reciprocal response?. Exp Econ 22, 506–529 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9561-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-018-9561-8