Abstract

Cosmetic products that contain malic, salicylic, hyaluronic acids and various antioxidants, which are popular worldwide, have made cosmeceuticals a popular cosmetic production sector. Typically, each component of cosmetics, regardless of its activity, may affect the thermal stability of the product. To investigate the thermal stability of regular cosmetics of interest, thermal activity monitor IV was applied to determine the thermokinetic parameters for stability assessment. Arrhenius equations and thermal safety software (for kinetic calculations and numerical simulations) were used. Considering the numerous additives in cosmetic products, individual components of cosmetic material mixed with other components are the primary factors for product deterioration. We examined samples of pure malic acid, pure salicylic acid, and individual acids mixed with copper or iron oxide under isothermal surroundings at 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C. The results of isothermal tests were compared with nonisothermal tests using Arrhenius equations, ASTM E698 method, and Flynn–Wall–Ozawa methods. The value of Ea between malic acid and salicylic acid became lower when mixed with CuO. The findings can be used to identify the optimal parameters for product design and establish a malic and salicylic acid database for developing a proactive loss prevention protocol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term “cosmetics” is derived from the Greek term “kosmetikes”, which means the accomplishment of adornment. The usage of cosmetics can be traced to 4000 years ago in ancient Egypt, where various materials were used as cosmetics and perfumes. Cosmetics were used in making sacrifices to ancient gods for obtaining peace [1, 2]. Presently, in the beauty and fashion industry, various materials are used as cosmetic ingredients. The advancement of science and technology has promoted the development of numerous functional personal care products. According to their functions, global personal care products can be classified into five categories: skin care products, perfumes, hair care products, makeup supplies, and body care products [3, 4].

Among these, skin care products are the most highly demanded in the market. Malic, salicylic, and hyaluronic acids and various antioxidants are the most common components of these products. Therefore, considering the effects of hydroxyl acids on the marketing of personal care products is vital. Although function and sensitivity are main concerns for these products, two other characteristics are worthy of notice: thermal stability and safety. To explore the characteristics of different cosmetic materials, their thermal stability has been examined [5, 6]. Although numerous burn and allergy cases have been caused by temperature-induced deterioration in the quality of skin care products during transport [7], studies on the thermal stability of alpha- and beta-hydroxyl acids are lacking.

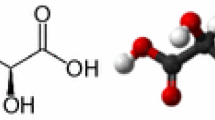

Investigating the thermal stability of alpha- and beta-hydroxyl acids and risks associated with hydroxyl acids is necessary. In this study, two types of hydroxyl acids, malic acid and salicylic acid, were investigated. Malic acid, an alpha-hydroxyl acid, is presented a bit in various foods ingested daily; it is used not only in food additives but also in skin care products. Malic acid can efficiently exfoliate the skin and adjust the pH of products [8, 9]. Salicylic acid, a beta-hydroxyl acid, has an excellent capability to exfoliate and clean pores on the skin. This acid causes little irritation; therefore, many personal care product manufacturers tend to include it in facial care products. Clinical trials have reported that salicylic acid effectively treats peeling acne vulgaris, textural changes, and inflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients [10, 11].

Most personal care products must be used and stored at a medium to low temperature. Under different conditions, the temperature may change slightly; therefore, investigating the effects at different temperatures is necessary. The thermal activity monitor (TAM) IV is a reliable microcalorimeter system. The TAM has been used for performing isothermal experiments involving different organic materials to evaluate important thermokinetic parameters under different isothermal conditions [12, 13]. Specifically, the TAM is applied to detect and record the thermal activity of malic acid, salicylic acid, and individual acids that are mixed with copper or iron oxide. Moreover, thermal stability parameters, namely heat flow and maximum peak power at time, have been obtained and employed to calculate apparent activity energy (Ea) using the Arrhenius equation and thermal safety software (TSS) [14,15,16,17,18]. The TSS was purchased from ChemInform Saint Petersburg Ltd., Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation.

Experimental

Sample preparation

To determine the thermal stability of common alpha- and beta-hydroxyl acids mixed with metal oxides in skin care products, malic acid, salicylic acid, CuO, and Fe2O3 were used for testing. Reagent-grade 95 mass% malic acid (C4H6O5, CAS No.: 97-67-6) with white crystals and reagent-grade 99 mass% salicylic acid (C7H6O3, CAS No.: 69-72-7) with white crystals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, Missouri, USA and Avantor Performance Materials Incorporation, Pennsylvania, USA, respectively. For the mixture samples, reagent-grade 99 mass% CuO and 98 mass% Fe2O3 were obtained from Showa Kako Corporation, Osaka, Japan. All test samples were received and saved in a humidity-controlled box under room temperature without further processing.

Thermal activity monitor IV

The application of TAM covers many areas, including stability temperatures [19], stability of DNA [20], thermal hazards of dicumyl peroxide [21], toxic effect of hexavalent chromium on microbial activity [22], and exothermic decomposition of cumene hydroperoxide [23]. We used the TAM IV to analyze the samples under isothermal conditions. The oil bath system in the TAM IV can provide extremely stable isothermal conditions. This system consists of two components: a 25-L isothermal oil bath groove and an outer oil bath groove. The temperature was governed by an outer heating thermostat and a microheater in the bottle of the oil bath groove. The operating temperature was maintained at 4–150 °C, and the sensor could reach 10 nW (deviation: ± 0.01 °C). Isothermal experiments are more effective in explaining slower reactions values than that in nonisothermal experiments, and the measured feature in TAM IV is passive. Moreover, the operation of an isothermal model is stricter than that of a nonisothermal model. Because of TAM IV’s excellent heating flow stability, even though the period of the experiment is long, the thermostat can highly accurately measure the heat flow with tiny difference. Moreover, a reference in calorimeters was compared and could be utilized to smooth the baseline noise. Hence, it can moderate the influence of thermostat fluctuations on the measured heat flow. Applying isothermal conditions in scanning experiments ensures accurate measurement of thermokinetic parameters [24]. The microcalorimeter of TAM IV was designed to assist heat generation from the reaction of samples via heat flow sensors. The thermoelectric sensors in TAM IV are connected with the sample and the isothermal thermostat heating sink; therefore, the thermoelectric sensors can probe the temperature difference and provide feedback to the sensor. The heat flow generation of samples is measured and recorded as voltage signs; then the signals can be transferred to the computer. In this study, we selected the vacuum/pressure ampoules, which can provide an appropriate environment for different types of samples during the measurement, referred to as sealed ampoules.

To perform the TAM IV isothermal experiments, three sets of 15 mg malic acid samples were poured in ampoules, and 15 mg of CuO and Fe2O3 were mixed separately in individual ampoules. Thus, pure malic acid, malic acid mixed with CuO, and malic acid mixed with Fe2O3 were investigated to determine changes in their thermal stability. For salicylic acid mixed with CuO and Fe2O3, the same mass ratio of mixtures was used; pure salicylic acid, salicylic mixed with CuO, and salicylic acid mixed with Fe2O3 were analyzed in other TAM IV tests. To determine the effects of different medium- to low-temperature conditions, the temperatures were controlled during the TAM IV tests at 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C.

Results and discussion

TAM IV experiments

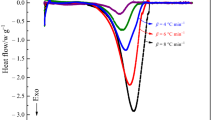

To determine the microchanges in the samples under isothermal conditions, 18 sets of TAM IV experiments (pure malic acid, malic acid mixed with CuO, malic acid mixed with Fe2O3, pure salicylic acid, salicylic acid mixed with CuO, and salicylic acid mixed with Fe2O3) were performed (Figs. 1, 2). Each set of experiments was conducted in triplicate, and one representative data set was selected and analyzed.

To obtain the reaction change of malic acid and salicylic acid, each set of the analyzed samples was poured in ampoules at 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C. Figure 1 presents the endothermal curve of pure malic acid, malic acid mixed CuO, and malic acid mixed with Fe2O3; solid malic acids were observed to melt because of heat accumulation in isothermal conditions. After the phase change, the endothermic reaction declined over time. For malic acid mixed with Fe2O3 at 120 °C, an exothermic peak appeared at approximately 20 h, at which the highest heat flow was 0.00405 W g−1, and the ΔHd was 124.6 J g−1. For pure malic acid and malic acid mixed with CuO, the highest heat flow was 0.00084 and 0.00181 W g−1, respectively, with no obvious exothermic reaction.

At 100 °C, exothermic and endothermic reactions were rare. Only a small but detectable exothermic reaction occurred in pure malic acid (ΔHd: 5.7 J g−1) at 18.3 h. The exothermic reaction of malic acid mixed with CuO was detected to have a ΔHd of 14.6 J g−1 at 4.5 h in isothermal experiments at 90 °C. The ΔHd of pure malic acid was higher than those of malic acid mixed with CuO and Fe2O3, which were 1.2 and 0.2 J g−1, respectively. The highest heat flow of the three samples was between 0.0001 and 0.00405 W g−1. At 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C, the three sets of malic acid samples were observed to be quite stable; Table 1 presents the thermokinetic parameters of the three samples.

Compared with malic acid, salicylic acid showed delayed endothermic and exothermic reactions during the experiments. At 120 °C, the exothermic reaction of salicylic acid mixed with CuO promptly reached the highest peak. Long-term endothermic reactions then occurred from 10 to 14 h. A small exothermic reaction began at 14 h and stabilized after 24 h, resulting in the highest heat flow (0.0036 W g−1) and a ΔHd of 6.3 J g−1. For the other sets of experiments, few major exothermic reactions were observed in pure salicylic acid (Fig. 2).

A melting reaction resulted in an endothermic reaction in salicylic acid mixed with CuO at 90 °C; however, this reaction was postponed compared with that at 120 °C, where it occurred from 9 to 14 h. The exothermic reaction at 120 °C occurred at 14.5 h and was very small; the highest heat flow was 0.00075 W g−1, and the ΔHd was 2.27 J g−1. According to the findings illustrated in Fig. 2, at 80 °C, the three sets of samples had weak exothermic reactions, with the highest ΔHd of 5.5 J g−1; the highest heat flows were distributed between 0.00010 and 0.00011 W g−1. The three salicylic acid samples were quite stable, and the values of the thermokinetic parameters are listed in Table 2.

Isothermal kinetics

To examine the thermokinetic parameters, the classical Arrhenius equation presented in Eq. (1) was adopted from the literature [25]:

where k is the reaction rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the apparent activation energy, R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1 K−1), and T is the absolute temperature. By taking the logarithm of Eq. (1), we can obtain Eq. (2):

In Eq. (2), A is considered a unique constant that does not change with temperature. By contrast, the value of k increases with temperature. Hence, Eq. (2) can be considered as the set of kinetic equations expressed in Eq. (3):

where T1, T2, and T3 are the set constant temperatures and k1, k2, and k3 are the maximum heat flow at different temperatures. We used the linear regression for lnk and T−1 from Eq. (3) to calculate − Ea R−1. The k was obtained from the respective maximum heat flow under different evaluated temperatures. Then, the value of minus slope times 8.314 and divided by 1000 equals Ea. Therefore, the Ea of pure malic acid, pure salicylic acid, or an acid mixed with CuO or Fe2O3 could be obtained.

Nonisothermal kinetics

Various methods, such as the ASTM E698 and Flynn–Wall–Ozawa methods, can be used to calculate the thermokinetic parameters. To compare the Ea obtained from isothermal and nonisothermal experiments, the ASTM E698 method was used.

Using this model-free method, we can apply the ASTM E698 method in the regression of \(\ln (\beta_{\text{i}} T_{\text{p}}^{ - 2} )\) against \(T_{\text{p}}^{ - 1}\); the regression slope is − Ea R−1 [26]. Another model-free method, the Flynn–Wall–Ozawa method, was used to calculate Ea without reaction model assumptions during nonisothermal experiments. The Flynn–Wall–Ozawa equation is expressed as Eq. (4) [27, 28]:

Analysis of thermokinetic parameters

To compare the different thermokinetic techniques in isothermal and nonisothermal conditions, the ASTM E698, Flynn–Wall–Ozawa, and Arrhenius methods were used to determine the Ea of malic acid, salicylic acid, and individual acids mixed with CuO and Fe2O3. Notably, the results of the ASTM E698 and Flynn–Wall–Ozawa methods, which were conducted through differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), were obtained from previous experiments.

TAM IV isothermal experiments were performed to observe the thermokinetic parameters and reaction changes of malic acid, salicylic acid, and individual acids mixed with CuO and Fe2O3. The obtained thermokinetic parameters were used to calculate the Ea by Eq. (3) (Table 1). The Ea of pure malic acid, malic acid mixed with CuO, and malic acid mixed with Fe2O3 was 113, 77, and 137 kJ mol−1, respectively. The Ea of pure salicylic acid, salicylic acid mixed with CuO, and salicylic acid mixed with Fe2O3 was 116, 78, and 91 kJ mol−1, respectively (Table 2). The Ea value of malic acid is similar to the literature [29]. However, the Ea value of salicylic acid is much higher than the literature [30].

From the ASTM E698 method, the average Ea in the malic acid experiments was approximately 88 kJ mol−1, and the average Ea in the salicylic acid experiments was approximately 62 kJ mol−1. Regarding the results of Flynn–Wall–Ozawa method, the Ea in the malic acid experiments was approximately 84 kJ mol−1, and that in the salicylic acid experiments was 99–161 kJ mol−1. The results reveal that the values of malic acid and salicylic acid Ea during isothermal experiments were lower than that during nonisothermal experiments.

TSS was also adopted to simulate the thermal parameters. In malic acid simulation, the exothermic reaction was assumed as two reaction stages, which are shown as Eqs. (5) and (6).

The exothermic reaction of salicylic acid was also assumed as two reaction stages, which are described as Eqs. (5) and (7).

From results of TSS simulation, Ea of malic acid was determined as 56–84 kJ mol−1. Ea of salicylic acid was determined as 91–116 kJ mol−1. The results of this simulation are close to the findings calculated from Flynn–Wall–Ozawa method.

Conclusions

The thermal stability of two types of hydroxyl acids, malic acid and salicylic acid, and their combinations with CuO and Fe2O3 was determined using the TAM IV in isothermal experiments. In this study, Ea calculated from isothermal method was different with the Ea value calculated from nonisothermal method, because the isothermal surrounding temperatures were lower than activation temperature in DSC tests. The Arrhenius method was used to calculate the Ea of malic acid and salicylic acid in isothermal experiments, yielding values from 77 to 137 kJ mol−1 and 78 to 116 kJ mol−1, respectively. The value of Ea between malic acid and salicylic acid both became lower when mixed with CuO. Adding Fe2O3 in malic acid slightly increased Ea, but the reason is not clear. The Ea value obtained from TSS simulation was similar to the result calculated from Flynn–Wall–Ozawa method. A modest long-term endothermic reaction occurred at 9–20 h in an isothermal experiment at 120 °C involving salicylic acid mixed with CuO. The melting reaction and phase changes were determined. The highest ΔHd was only 6.3 J g−1. Almost no exothermic reaction occurred in isothermal experiments involving salicylic acid. Therefore, we can conclude that the examined mixtures are quite stable below 120 °C.

References

Iwegbue CM, Emakunu OS, Nwajei GE, Bassey FI, Martincigh BS. Evaluation of human exposure to metals from some commonly used bathing soaps and shower gels in Nigeria. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017;83:38–45.

Kaličanin B, Velimirović D. A study of the possible harmful effects of cosmetic beauty products on human health. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2016;170(2):476–84.

Shimpi SS. Structural equation modeling for men’s cosmetics behavior research. Indian J Market. 2016;46(7):36–54.

Ingram AL, Nickels TM, Maraoulaite DK, White RL. Thermogravimetry–mass spectrometry investigations of montmorillonite interlayer water perturbations caused by aromatic acid adsorbates. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;126(3):1157–66.

Gálico DA, Nova CV, Bannach G. Polymorphism in propyl gallate recrystallized with acetone. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;128(1):611–4.

Bezerra GSN, Pereira MAV, Ostrosky EA, Barbosa EG, de Moura MdFV, Ferrari M, Aragão CFS, Gomes APB. Compatibility study between ferulic acid and excipients used in cosmetic formulations by TG/DTG, DSC and FTIR. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;127(2):1683–91.

Iwegbue CMA. Safety evaluation of the metals in some brands of nail polish in Nigeria. J Verbrauch Lebensm. 2016;11(3):271–8.

Telegdi J, Trif L, Nagy E, Mihály J, Molnár N. New comonomers in malic acid polyesters. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;129(2):991–1000.

Van Staden J, Volschenk H, Van Vuuren H, Viljoen-Bloom M. Malic acid distribution and degradation in grape must during skin contact: the influence of recombinant malo-ethanolic wine yeast strains. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2017;26(1):16–20.

Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicylic acid chemical peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25(1):18–22.

Huang AC, Chen WC, Huang CF, Zhao JY, Deng J, Shu CM. Thermal stability simulations of 1,1-bis(tert-butylperoxy)-3,3,5 trimethylcyclohexane mixed with metal ions. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;130(2):949–57.

Chen WC, Lin JR, Liao MS, Wang YW, Shu CM. Green approach to evaluating the thermal hazard reaction of peracetic acid through various kinetic methods. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;127(1):1019–26.

Willms T, Kryk H, Oertel J, Lu X, Hampel U. Reactivity of t-butyl hydroperoxide and t-butyl peroxide toward reactor materials measured by a microcalorimetric method at 30° C. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;128(1):319–33.

Wang Y, Xia X, Zhu J, Li Y, Wang X, Hu X. Catalytic activity of nanometer-sized CuO/Fe2O3 on thermal decompositon of AP and combustion of AP-based propellant. Combust Sci Technol. 2010;183(2):154–62.

Tsai LC, Tsai YT, Lin CP, Liu SH, Wu TC, Shu CM. Isothermal versus non-isothermal calorimetric technique to evaluate thermokinetic parameters and thermal hazard of tert-butyl peroxy-2-ethyl hexanoate. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2012;109(3):1291–6.

Tsai YT, You ML, Qian XM, Shu CM. Calorimetric techniques combined with various thermokinetic models to evaluate incompatible hazard of tert-butyl peroxy-2-ethyl hexanoate mixed with metal ions. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2013;52(24):8206–15.

Wang CP, Yang Y, Tsai YT, Deng J, Shu CM. Spontaneous combustion in six types of coal by using the simultaneous thermal analysis-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy technique. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;126(3):1591–602.

Deng J, Zhao JY, Xiao Y, Zhang YN, Huang AC, Shu CM. Thermal analysis of the pyrolysis and oxidation behaviour of 1/3 coking coal. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2017;129(3):1779–86.

Whitmore MW, Wilberforce JK. Use of the accelerating rate calorimeter and the thermal activity monitor to estimate stability temperatures. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 1993;6(2):95–101.

Nafisi S, Saboury AA, Keramat N, Neault JF, Tajmir-Riahi HA. Stability and structural features of DNA intercalation with ethidium bromide, acridine orange and methylene blue. J Mol Struct. 2007;827(1):35–43.

Hou HY, Liao TS, Duh YS, Shu CM. Thermal hazard studies for dicumyl peroxide by DSC and TAM. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2006;83(1):167–71.

Yao J, Tian L, Wang Y, Djah A, Wang F, Chen H, Su C, Zhuang R, Zhou Y, et al. Microcalorimetric study the toxic effect of hexavalent chromium on microbial activity of Wuhan brown sandy soil: an in vitro approach. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2008;69(2):289–95.

Hou HY, Shu CM, Duh YS. Exothermic decomposition of cumene hydroperoxide at low temperature conditions. AIChE J. 2001;47(8):1893–6.

Chiang CL, Liu SH, Lin YC, Shu CM. Thermal release hazard for the decomposition of cumene hydroperoxide in the presence of incompatibles using differential scanning calorimetry, thermal activity monitor III, and thermal imaging camera. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;127(1):1061–9.

Hao YH, Huang Z, Ye QQ, Wang JW, Yang XY, Fan XY, Li YL, Peng YW. A comparison study on non-isothermal decomposition kinetics of chitosan with different analysis methods. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2016;128(2):1077–91.

Saha B, Ghoshal A. Thermal degradation kinetics of poly (ethylene terephthalate) from waste soft drinks bottles. Chem Eng J. 2005;111(1):39–43.

Wang J, Jia H, Tang Y, Xiong X, Ding L. Thermal stability and non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of metallocene poly (ethylene–butene–hexene)/high fluid polypropylene copolymer blends. Thermochim Acta. 2017;647:55–61.

Bisinella RZ, Ribeiro JC, de Oliveira CS, Colman TA, Schnitzler E, Masson ML. Some instrumental methods applied in food chemistry to characterise lactulose and lactobionic acid. Food Chem. 2017;220:295–8.

Braud C, Bunel C, Vert M. Poly (β-malic acid): a new polymeric drug-carrier. Polym Bull. 1985;13(4):293–9.

Matyasovszky N, Tian M, Chen A. Kinetic study of the electrochemical oxidation of salicylic acid and salicylaldehyde using UV/vis spectroscopy and multivariate calibration. J Phys Chem A. 2009;113(33):9348–53.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Anhui Province Education Department Natural Sciences Key Fund, China (Grant No. KJ2017A078). The assistance of Prof. Olive J. Hao, YunTech, Feng Tay Chair Professor is acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Liu, SH., Huang, AC. et al. Effects of mixing malic acid and salicylic acid with metal oxides in medium- to low-temperature isothermal conditions, as determined using the thermal activity monitor IV. J Therm Anal Calorim 133, 779–784 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7003-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-018-7003-7