Abstract

Previous research mostly defines the benefits of work as the absence of unemployment’s negative outcomes or as benefits to employers, such as increased productivity. This study uses mixed methods to investigate the ways that work can enhance the well-being of the worker. Two hundred and two participants from a rural area participated in semi-structured qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys. Participants’ qualitative discussions of work in the interviews were coded with grounded theory. The majority (74.8 %) of participants mentioned work at least once during the interview, which focused on prominent moments in their life stories, and 53.3 % of work mentions were positive. Two main themes encompassing the protective benefits of work arose: self-oriented benefits and other-oriented benefits. Each main theme was further divided into three subthemes. Self-oriented subthemes were autonomy, personal development, and empowerment; other-oriented subthemes were providing for dependents, generativity, and helping others. Participants spoke about how each of these benefits enhances their well-being and happiness. The empowerment subtheme was positively correlated with workplace integration and negatively correlated with financial strain. This study uncovered protective benefits of work that have not been addressed by previous scholarship. Qualitative data provided the flexibility to explore work-related domains for which quantitative scales do not currently exist. Work is one of the main activities of most adults, and the study of the psychological benefits of work can improve our understanding of adult well-being and happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Unemployment has been found to be a risk factor for a range of adverse consequences in terms of both physical and psychological health (Henkel 2011; Herbig et al. 2013; Jin et al. 1995). However, there has been comparatively less research on the ways employment can serve as a protective factor. Existing research tends to define the benefits of employment either as the absence of negative outcomes (Bond et al. 2001; Rosenthal et al. 2012; Zabkiewicz 2010) or the extent to which employee well-being predicts better job performance, retention, and other factors that focus more on employer needs (Hosie et al. 2007; Rothmann and Essenko 2007; Shuck and Reio 2014). There has been relatively less attention paid to the personal and social benefits that workers derive from their jobs and careers. The current study uses mixed methods analysis to explore ways in which work can contribute to happiness and well-being, providing psychosocial benefits that extend well beyond the workplace.

1.1 Past Research on Work Status

One of the most studied aspects of work is the link between unemployment and numerous negative personal outcomes. Unemployment has been associated with an increase in all-cause mortality (Jin et al. 1995; Roelfs et al. 2011) as well as suicide (Jin et al. 1995; Stuckler et al. 2009; Yur’yev et al. 2012). Unemployment has been found to be a major risk factor for both anxiety and depression (Herbig et al. 2013; Levecque et al. 2007) as well as increased tobacco consumption (Montgomery et al. 1998; Nandi et al. 2013), alcohol consumption, frequency of binge drinking (Claussen 1999; Henkel 2011; Montgomery et al. 1998), and alcohol dependence and abuse (Herbig et al. 2013). Recent unemployment has been correlated with increases in familial stress and domestic violence against women (Kyriacou et al. 1999; Stöckl et al. 2011). In terms of physical health, unemployment is associated with lower self-rated health measures (Luo et al. 2010). It has been linked to higher cholesterol (Mattiasson et al. 1990; Weber and Lehnert 1997) and heart rate variability (Jandackova et al. 2012), both risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Unemployment even has implications for one’s social health; studies show that the unemployed experience social isolation and segregation and thus lack the social resources to find employment, perpetuating the trend (Russell 1999; Zeng 2012).

1.2 Positive Outcomes of Employment

While the negative implications of unemployment are clear, there has been relatively little research on the ways in which employment enhances well-being. The literature that does exist mostly defines the benefits of work as the absence of negative outcomes. In a literature review of longitudinal studies assessing the effects of reemployment, Rueda et al. (2012) found that returning to work after a long period of unemployment was associated with fewer mood, anxiety, and psychotic symptoms, lower incidence of alcohol abuse, lower mortality, higher self-esteem, and higher quality of life. Other research in this area focuses on targeted populations, showing that employment enhances well-being for those commonly excluded from the workforce. Among working age adults with mental illness, employment was associated with greater symptom recovery and a higher overall quality of life (Bell et al. 1996; Bond et al. 2001; Van Dongen 1996). Employment predicted better physical health, mental health, and quality of life amongst those with physical disabilities (Hall et al. 2013), HIV (Rueda et al. 2011), and breast cancer (Timperi et al. 2013). Similar health benefits were associated with employment in populations commonly encouraged to stop working, such as new mothers (Frech and Damaske 2012) and retirement-age adults, even after controlling for baseline health (Zhan et al. 2009).

1.3 Work and Global Measures of Well-Being

Several workplace characteristics have been shown to reduce stress and increase global well-being. Brown and Leigh (1996) developed the widely-used Psychological Climate Measure (PCM), defining a positive psychological climate in the workplace as the presence of supportive management, role clarity, contribution, recognition, self-expression, and challenge. The PCM was shown to predict low emotional exhaustion and depersonalization as well as higher accomplishment and well-being (Shuck and Reio 2014). Other research shows that worker well-being was predicted by high perceived levels of emotional support and high levels of control (Stansfeld et al. 2013), the presence of spiritual values in the workplace (Arnetz et al. 2013; McKee et al. 2011), as well as defined roles, interpersonal training, and elimination of task overload and underload (Danna and Griffin 1999).

1.4 Research Gaps in Work Literature

Research is largely lacking on the ways in which employment provides specific positive psychological and social benefits that do not simply help avoid negative health outcomes or increase work productivity. Discussions of resilience and well-being across the lifespan highlight that the absence of mental health symptoms is only one facet of psychological functioning, highlighting the need for more research that examines the presence of positive indicators of well-being (Grych et al. in press). Some researchers acknowledge the ‘spill-over’ from job-related wellness into non-work life (Danna and Griffin 1999), but the interest in employee well-being has been primarily on its effect on job performance and engagement, a relationship known as the ‘happy productive worker’ thesis (Hosie et al. 2007). A few studies have attempted to go beyond work-related outcomes, finding that work engagement, defined as vigor and dedication to one’s job, predicts one’s own and romantic partner’s happiness at home (Helliwell and Huang 2011; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al. 2014). These studies represent an important step by widening the focus beyond occupational well-being. However, little is known about factors other than work engagement, or the factors that might influence work engagement, that can optimize the effect of work on overall well-being in other domains.

1.5 Goals of the Current Study

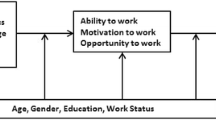

Qualitative data provides the flexibility to fill the current gaps in research on the link between work and well-being. Particularly in open-ended interviews, participants are able to direct the discussion toward the aspects of their lives they deem most important rather than only those initially of interest to the researchers. Furthermore, participants can shape their own responses and are not limited to specific response categories. While scale-based quantitative research is extremely important and enables statistical analysis, qualitative data allows researchers to explore factors for which scales do not yet exist. Particularly in relatively nascent research areas, qualitative analysis can serve as a starting point, uncovering important variables that might be the focus of future qualitative and quantitative research. Therefore, the goal of the current project was to analyze participants’ discussions of the ways work positively impacted their lives, using their own words to discover the processes through which work has positive, protective effects on one’s psychosocial health. Additionally, mentions of work were counted and categorized to create quantitative variables, which were analyzed with survey-based quantitative measures.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

The participants were 202 individuals from Southern states who completed a computer survey and in-depth interview as part of a larger study on resilience and character development. Participants’ mean age of was 31.5 (SD = 13.7), ranging from 12 to 69. Of these participants, 35.4 % were male and 64.6 % were female. In terms of ethnicity, 77.4 % of the sample reported being European American/White non-Hispanic, 13.3 % were African American/Black non-Hispanic, 5 % of participants reported being multiracial, 3 % were Latino, .5 % were Native American or Alaskan Native non-Hispanic, and .5 % were Asian non-Hispanic, with the remaining not reported their ethnicity.

Regarding employment demographics, 25.2 % of participants were employed full-time, 14.4 % were employed part-time, 18.8 % were laid off or unemployed, 20.3 % were students, 9.4 % were homemakers, 7.9 % were disabled or too ill to work, and 1.5 % were retired. Looking at total household income, 47.5 % of participants reported earning $20,000 or less per year, 31.8 % reported earning $20,000 to $50,000, and 18.7 % reported earning $50,000 or more. When asked about their area of residence, 22.7 % of participants reported living in a “rural area” with a population of less than 2500 people; 66.8 % reported living in a “small town” with a population between 2500 and 20,000 people.

2.2 Procedures

Participants were recruited through a range of advertising techniques. The majority of participants (76 %) were recruited at local community events, such as festivals and county fairs. Word-of-mouth was the second most productive recruitment strategy, accounting for 12 % of participants. The remaining 12 % were recruited through other strategies, including flyers, newspaper and radio ads, and direct mail. This wide range of recruitment strategies allowed us to reach segments of the population who are rarely included in psychological research. Interviewers offered to meet participants in multiple locations throughout the community (including our research center, other campus locations, and their homes), during daytime or evening hours. This flexibility provided people with limited availability or transportation an opportunity to participate. This region of Appalachia still has limited and often unreliable cellular and internet service; therefore, the survey software was specifically chosen to operate without internet connectivity. The survey was administered using Snap10 survey software on laptops and iPads. An audio option was available. Technical problems (such as iPads overheating) and time limitations prevented some individuals from completing the survey; overall, the completion rate was 85 % and the median completion time was 53 min. This is an excellent result by current survey standards, especially considering the fairly long survey, with current completion rates often under 70 % (Abt SRBI 2012) and sometimes under 50 % (Galesic and Bosnjak 2009). All participants received a $30 Walmart gift card and information on local resources. All procedures were conducted in accordance with APA ethical principles and approved by the IRB of the study’s home institution.

Participants who took the survey were offered the opportunity to subsequently participate in a qualitative interview until the target of 200 qualitative interviews was reached. The interviews asked participants to talk about various facets of their life story, including prominent moments (i.e. high points, low points, and turning points), life challenges, and coping strategies. The interviews were semi-structured, requiring interviewers to follow a script but allowing them to tailor primary and follow-up questions to each participant. Interviews were conducted privately in a quiet location selected by the participant—usually in the research office or in the participants’ homes. Audio of the interviews was recorded and later transcribed verbatim. Participants received an additional $50 Walmart gift card for their participation in the interview. The Institutional Review Board of the study’s home institution approved all procedures. A total of 208 interviews were recorded, but six were not audible due to technical problems, leaving a final sample of 202 for data analysis.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Workplace Integration

The four-item Workplace Integration Scale (Hamby et al. 2013, 2015, adapted from U.S. Air Force 2011) measures workplace cohesion and the degree to which work is integrated into one’s personal life by presenting participants with a statement such as, “The people at my job really stick together.” The responses were on a four-point likert scale, with “1” reading “Not true about my workplace” and “4” reading “Mostly true about my workplace.” Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was .85. Participants completed this scale as part of the computer-assisted self-interview. Reliability and construct validity were established in a pilot study.

2.3.2 Financial Strain Index

The Financial Strain Index (Hamby et al. 2011) assesses perceived economic pressure. It consists of five items intended to evaluate the respondents’ current financial situation, such as “You don’t have enough money to pay regular bills.” Participants responded on a 3-point Likert scale, with “1” denoting “Not true”, “2” denoting “A little true”, and “3” denoting “Very true.” Answer categories were assigned a value and summed, with higher scores indicating increased financial strain. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for this scale as found to be .82.

2.4 Data Analysis

We utilized grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss 1990; Walker and Myrick 2006) to derive codes, categories, subcategories, and ultimately themes from participants’ own words. This was done in three phases in accordance to Strauss and Corbin’s later iteration of grounded theory (Walker and Myrick 2006). In the “open phase,” the first author reviewed 28 interview transcripts in which work was discussed at some length, using participants’ own words to develop a list of the ways through which work provides protective benefits. It should be noted that work was not asked about specifically in the interview questions. Rather, participants were asked about a number of aspects of their life narrative and coding was done of interview segments where work was mentioned spontaneously by participants. In the second phase, the “axial phase,” these initial codes were presented to the remaining three authors along with exemplifying quotations and interviews. The research team collaborated to make connections between categories and subcategories to create higher order, more condensed codes. These codes were subsequently applied to the remaining interviews and further refined based on the interview content. In the third or “selective” phase, the authors discussed and reached consensus, integrating and combining codes into two core themes. Each theme was further divided into three subthemes.

Work mentions were counted and coded as positive, negative, or neutral. Participants who mentioned work during discussions of adversity were categorized as experiencing job-related adversity, experiencing unemployment as adversity, or using their job to cope with adversity. Associations of these variables with financial strain and workplace integration were tested with correlations.

3 Results

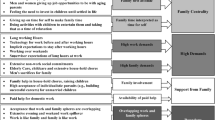

Two core themes that reflect the processes through which work can serve as a protective factor arose from qualitative analysis: those that are self-oriented and those that are other-oriented. Each of these themes was comprised of three related but distinct subthemes. They are described below along with expository quotes from the interviews as well as the percentage of interviews in which they arose (out of the interviews in which work was mentioned). These themes are the ones that emerged the most frequently, consistently, and clearly based on analysis using grounded theory. A summary of these results can be found in Table 1.

3.1 Self-Oriented

Many participants spoke about the ways in which their work directly contributed to their own well-being. While these discussions were all related by the orientation toward the self, three distinct subthemes emerged amongst them. Some participants (11.3 %) valued work for the personal autonomy it provided. Others (9.9 %) viewed their work as a source of personal development, instilling skills, lessons, and responsibility. Finally, several participants (9.3 %) spoke of work as empowering, contributing to a sense of mastery and pride.

3.1.1 Autonomy

Many participants valued their job and the income it provided for allowing them to be financially independent, which in turn provided a sense of personal autonomy. A 22-year-old female named her first job as a positive turning point in her life: “The first job is what helped out a whole lot….It was my money coming in…excited about getting my own place…. I wanted the job so I can get out on my own.” After discussing not having a job as a low point in her life, a 41-year-old female said, “I really hate depending on people…. Once I got the job I saved up my money to get my own place, and been on my own ever since.” A 49-year-old female described a similar aversion to depending on people and named having a job as a core value: “[Having a job] means having money in my pocket. I don’t have to go out and ask…to borrow money…. Because without a job,…you ain’t really got nothing.” While these participants discussed their ability to rely on others for financial assistance, they wanted to work and valued the personal autonomy that employment provides.

3.1.2 Empowerment

Implicit in these participants’ discussions of autonomy is pride by virtue of being employed. A related but distinct subtheme that emerged was work itself (not just employment status) as empowering—a source of pride and mastery. A 43-year-old law enforcement officer made the distinction between simply being employed and having a job that he is proud of: “You’ve got to have pride in what you do…. If you’re not proud of what you’re doing, you need to be doing something else…. I’ve got a lot of pride in what I do.” A 53-year-old female spoke more specifically, describing a challenging but ultimately rewarding job as a correctional officer in an all-male prison: “For me to be able to…gear up…and face those challenges and those circumstances and stand strong and proud, not to roll over…. Because you’re standing face to face in a dangerous situation, and you have to be the authority figure.” Similarly, a 32-year-old female named job success as one of her core values: “Being successful at what I chose to do…. How I do at work. How I am perceived at work. How my co-workers…and my bosses like me…All that translates to: Am I good at what I do? And I believe that I am.”

3.1.3 Personal Development

Several participants also discussed work as a source of learning that contributed to their personal development. For some, this came in the form of specific lessons. A 23-year-old female described something she learned from being a camp counselor that she will likely take with her in her future professional endeavors: “Being a mentor this summer taught me a lot of things. It taught me the difference between being someone who’s respected and being someone who’s liked.”

For other participants, employment provided specific lessons as well as a broader developmental experience. Naming his first job as a high point in this life, a 20-year-old male said,

I got the chance to go out and meet people… and learned some things and different fields.…It made me care about something other than myself. Because I didn’t have to do nothing, but now once I got the job I actually learned a lot about how to manage the money and pay the bills, help out….So this job actually…is what made me responsible.

Similarly, a 32-year-old male described joining the military as a high point:

It was new…I wasn’t that much into fitness, but it got me a lot healthier. I was…about 375 pounds at the time, and…got down to about 210, 220, and had a regular regiment of…working out every morning and having a job during a day on a regular cycle of…It kind of straightened me out….I was heading down the wrong road.

For this participant, his employment in the military provided physical benefits through the fitness regimen but also psychological benefits by instilling responsibility and discipline.

3.2 Other-Oriented

Many participants discussed how work indirectly enhances their well-being via the way that it benefits others. This other-oriented theme was also divided into three subthemes. Some participants (10.6 %) valued their work because it allowed them to provide for their dependents. Others (7.9 %) were able to exercise altruism in their work through generativity, a concern for future generations that often manifests in the desire to pass on knowledge (McAdams and De St Aubin 1992). Many participants (9.3 %) found the opportunity within their work context to directly help others, often going above and beyond their traditional job responsibilities.

3.2.1 Providing for Dependents

Some participants discussed their ability to support themselves, but sometimes that was not enough; many also had to provide for their families and valued their job for allowing them to do so. A few participants spoke of meeting the most basic needs of their dependents. When asked about the low point in his life, a 43-year-old-male said, “The lowest point that I can think of…is the times that I didn’t have a job. The times I couldn’t provide for my family.”

However, many participants wanted to provide more than the bare essentials. They wanted to give their dependents, particularly their children, things they wanted, not only things they needed. A 31-year-old female, who was disabled and unemployed at the time of the interview, said: “I want to go back to work. I want to work for my kids….[My kids] still get stuff, but I want to do more for them.” Even though she could meet her children’s basic needs with disability checks, this mother wanted to go back to work so that her children can have more—to have their higher needs met. A 20-year-old female, also unemployed at the time, expressed a similar desire: “I want to get a job working, I want my kids to not have everything they want but you know have things…pretty much everything they need and…some things they want. I’d be happy.” She recognized that she could give her children absolutely everything they wanted, but she wanted to provide at least a few luxuries. A 28-year-old female described very specific goals for providing for her daughter. When asked about her hopes for the next ten years, she said: “My goal is to…get my RN license…. to make my life comfortable, to make my daughter’s life comfortable… to have her a car for graduation…to send her off…to college where she don’t have to use financial aid.” She realized that attaining her RN (Registered Nurse) license would enable her to make life not just livable but comfortable for herself and her daughter.

3.2.2 Generativity

While the above participants wanted to provide financial support for their children, others were concerned about supporting future generations by passing down knowledge and setting a positive example, a desire termed generativity. A 43-year-old male law enforcement officer expressed hope that his grandson would follow in his footsteps: “I’m hoping he…goes to college and gets his bachelor’s degree in justice because he’s…all the time talking about how he wants to be a police officer…. He’s already wanting to learn how to do what I do.” For one participant, a 43-year-old female with a visual disability, finding work was especially important for her to set an example for her younger family members, who inherited her disability. She said, “I really want to get a job…because I want…my children…and…my grandchildren to know that…even though you’re disabled, try and get out there and do what you can.” For her, working was a way to demonstrate her value and ability to her children and grandchildren in order to instill in them a sense of confidence and self-worth.

However, generativity does not exclusively manifest in concern for one’s own children or grandchildren. When asked about a high point in her life a 69-year-old female talked about working with children as a zookeeper: “These young people…were engaged…with the animals…as I had been. And I felt like I had successfully communicated to them…the ‘beingness’ of these creatures…the potential for more people…to learn about these creatures.” In fact, generativity need not involve a major age difference. One 42-year-old female manager in a governmental agency said, “I don’t feel like,…through my career path, that I’ve had much in the way of support and guidance.… Because of that, I try to mentor others.” Taking advantage of her managerial role, this participant wanted to provide the career guidance she herself never received.

3.2.3 Helping Others

Work also allowed several participants to display more general altruistic behavior and to help those in need. In the most striking instances, participants went above and beyond their strict job responsibilities. Some were actually in traditional helping professions and were able to exercise altruism on a daily basis. When asked about positive behavior, a 60-year-old female priest said: “As a priest in communities,…one of the benefits of that job is you get to care for people …. That’s the motivator…. I always loved going to talk to people who…were feeling especially lonely or…needed somebody to talk to…so you go the extra mile.” Although helping is a defining aspect of her job, this priest still emphasized taking her own initiative by reaching out and “go[ing] the extra mile.”

However, many participants not in traditional helping professions also found profound ways to help others within their job context. When asked about an episode of particularly positive behavior she had exhibited, a 40-year-old female chef provided this story of a troubled employee:

She just was a bad employee…a drug and alcohol addict….She just had a really bad attitude….And just by getting to know her, we got her to go to rehab. And she’s been clean and sober for six years now….She said, ‘If it hadn’t been for you giving me a second chance and helping me to understand that there is more out there.’ And I still work with her today.…It makes me feel good knowing that she went from where she was to excelling and trying to do better and being more positive in her life.

While strict professional standards would have probably led to this employee’s termination, the participant instead saw an opportunity to help a struggling young woman. A 41-year-old male law enforcement officer described an instance of positive behavior while in a grocery store:

I…saw a guy that shoplifted. The stuff that he was shoplifting was pertaining to babies….I caught him, took him into custody, found out he’d just got laid off from his job. So, instead of arresting him and taking him to jail and…away from his kids, I paid for his merchandise and gave him forty dollars extra.

Again, a strict adherence to the law and his job responsibilities would have required this participant to arrest and charge this man, but he decided to follow a higher moral standard and help the father in need.

3.3 Subthemes, Workplace Integration, and Financial Strain

Correlations were run between endorsement of each subtheme and scores on workplace integration and financial strain. Endorsement of work as empowering was positively correlated with Workplace Integration, r(78) = .22, p = .048, and negatively correlated with financial strain, r(186) = −.18, p = .012. Other subthemes did not yield significant correlations with workplace integration of financial strain. Because the subthemes were not mutually exclusive (participants could endorse more than one), many, particularly the self-oriented subthemes, were moderately correlated with one another. The full correlation matrix of all study variables can be found in Table 2.

3.4 Positivity of Work Mentions

Of all participants, 74.8 % mentioned work at least once during their interviews (Table 3). After counting and categorizing all mentions of work, 53.3 % were positive, 27.7 % were negative, and 19 % were neutral (Table 4). Work was a common topic when participants were asked about adversity, with 39.7 % mentioning it while discussing adversity. However, of these participants, only 30 % actually discussed adversity caused by or occurring at work; 37.5 % referred to unemployment as adversity, and 32.5 % discussed their work as a means of coping with adversity in a different area of their lives (Table 5).

Correlations were run between the counts and categorizations of work mentions and scores on the workplace integration and financial strain. A significant relationship was found between scores on the workplace integration scale and the count of negative work mentions, which were moderately and negatively correlated, r(78) = −.33, p = .003. Participants who reported higher workplace integration tended to make fewer negative work mentions. No significant relationship was found between workplace integration and the count of positive work mentions. Discussing unemployment as an adversity was significantly correlated with financial strain, r(186) = −.26, p < .001.

4 Discussion

Several diverse but interconnected themes encompassing the benefits of work arose through our analysis of qualitative interviews. Many participants’ discussions of work involved primarily self-oriented pathways to enhanced well-being and happiness. Of these participants, some valued the feeling of autonomy gained by being financially independent. Others found their work to be empowering, providing a sense of mastery and pride. Some participants saw work as an opportunity for personal development, instilling important skills, lessons, and a sense of responsibility. Perhaps less expectedly, many discussed how work provided opportunities for altruism; work benefited these participants by allowing them to benefit others. These participants valued their jobs for providing opportunities to support their dependents, pass down lessons to younger generations, and help others in need. Many of the subthemes were weakly to moderately correlated with one another, indicating that they represent related but distinct constructs.

These findings add to the existing literature by exploring the positive aspects of work—not only the absence of the negative consequences of unemployment. They expand upon the findings that positive work experiences can have a positive spill-over into non-work domains (Culbertson et al. 2012; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al. 2014) by describing potential processes through which employment may enhance well-being. While themes such as altruism, generativity, empowerment, and personal development pertained to opportunities specific to individuals’ work environments, they emerged across several job contexts. Further research exploring variations between different occupations and fields would be worthwhile to add nuance to these findings. Previous research has demonstrated that workers who are able to exercise their individual strengths within their occupational setting reported higher job satisfaction, pleasure, work engagement, and meaning (Harzer and Ruch 2013; Littman-Ovadia and Steger 2010). In our study, participants who were able to utilize their strengths in order to help others, benefit a younger generation, or obtain a sense of empowerment reported these instances as positive work experiences from which they derived well-being. Other literature has looked specifically at work empowerment, finding that it enhances self-efficacy, motivation, and commitment (Liu et al. 2007). However, the focus of these studies is ultimately on resulting work performance, whereas our findings demonstrate that the benefits of work empowerment are not limited to the occupational setting. Our participants chose to tell stories of work empowerment as representative high points or instances of positive behavior over their entire lifetimes.

Unlike the themes discussed above, personal autonomy and providing for dependents do not appear to be tied to specific job-related opportunities but rather arise from the general experience of paid employment. One would probably not derive the same sense of personal autonomy or satisfaction of supporting dependents by obtaining income from other means, such as from governmental or familial assistance. Again, while these themes arose occurred diverse professions, research directly comparing occupational contexts is necessary to uncover potential differences.

Taken together, our themes suggest that work is capable of enhancing well-being on three levels: (1) by providing income, (2) by providing autonomy and satisfaction from earning one’s own income, and (3) by providing various opportunities to demonstrate value and efficacy to benefit one’s self and others. Alternatively, our themes can be analyzed in the context of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (1943). The most obvious benefit of work is the paycheck, which in turn allows people to meet their most basic needs—food, water, and shelter—that form the base of Maslow’s pyramid. Some participants discussed stability, which falls under safety and security needs in Maslow’s second level. However, many participants emphasized the fulfillment of higher needs, those in the top three levels of Maslow’s pyramid: Providing for dependents helps to fulfill love and belonging, autonomy, mastery, and personal development constitute self-esteem needs, and opportunities for altruism and generativity fall under self-actualization.

Previous research also connects various indicators of well-being to each of the themes that emerged in our analysis. In terms of the self-oriented subthemes, autonomy is considered to be an important contributor to well-being (Ryff and Singer 2008) and was found to be a better predictor of well-being than wealth across multiple cultures (Fischer and Boer 2011). Learning occupational skills has been shown to enhance self-efficacy and self-esteem (Creed et al. 2001), and mastery is a strong predictor of subjective well-being as well as lower depression and anxiety symptoms (Burns et al. 2011). A recent study found that low mastery is associated with perceived poverty, or “feeling poor,” even when controlling for objective income level (Karraker 2014).

The second major class of themes emerging from the data was other-oriented. The ability to provide for dependents is an important aspect of caregivers’ well-being. In a qualitative study, impoverished parents tended to take personal responsibility for economic failings and associated them with bad parenting, and the stressful and time-consuming struggle to provide had a negative impact on virtually every aspect of the parents’ lives (Russell et al. 2008). This is consistent with research that has found that the psychological benefits of parenthood are hampered by limited financial resources (Umberson et al. 2010).

Generativity and helping behavior also were prominent in the narratives of some participants. Research shows that generativity is a strong indicator of psychological well-being (An and Cooney 2006), posttraumatic resilience (Ardelt et al. 2010), and positive societal engagement (Cox et al. 2010), particularly for adults in mid to late life. Likewise, altruism and helping behavior are associated with well-being and positive affect (Kahana et al. 2013) as well as posttraumatic well-being (Frazier et al. 2013). The benefits of altruism were found to be strongest when they resulted from autonomous motivation (Weinstein and Ryan 2010), like the instances in which our participants went above and beyond their traditional job descriptions to help others. Because these themes have been linked to well-being and were specifically discussed as benefits of work, they might serve as mediating links between employment and well-being.

4.1 Limitations

There are some limitations to the current study that should be acknowledged. The sample is large relative to other qualitative research, but it is fairly homogenous in terms of race and socioeconomic status. These demographics are consistent with the geographic region under consideration, but caution still should be taken when generalizing these findings to other populations. This study is also not meant to be a comprehensive review of all the effects of employment had on participants. Some participants (27.7 %) discussed their work or unemployment as a source of stress and adversity, but we limited the scope of analysis to the positive aspects of work in order to fill the major research gaps discussed above. Further, we exclusively relied on single informant self-report. Future studies might utilize other informants who know the participants well, such as parents, spouses, close friends, and children.

The quantitative analyses yielded interesting but limited findings, probably because the number of participants endorsing each subtheme is relatively small for quantitative analysis.

One limitation to note is that we did not have systematic data on each participant’s occupation. This was not an initial variable of interest of the larger study and was only available for some participants who brought it up spontaneously during their qualitative interviews. Therefore, data obtained from participants in a range of occupations were included in the same analyses under a single interpretive framework. This does limit the interpretation and implication of our findings because we cannot speak to factors specific to particular job contexts or occupational fields.

There are other limitations that accompany all mixed methods research, such as the potential for subjective interpretation and researcher bias. However, by grounding the themes in participants’ own words, we avoided the latter limitation as much as possible. Participants were never directly asked to talk about work, and interviewers did not have with any preconceived hypotheses or specific research interests regarding employment. Any discussions of work occurred because the participants brought it up themselves and viewed it as an important aspect of their lives.

4.2 Implications

This study opens the door for future qualitative and quantitative research on the protective benefits of work. While the participant-directed interview style was an important strength of this study, further qualitative research could also ask participants more directly about employment and explore their responses in greater depth. This research should also collect data reflecting participants’ jobs so that thematic commonalities and differences across fields can be analyzed. Researchers might also utilize other established methods of qualitative analysis to complement our grounded theory approach. Once our qualitative themes have been further studied within specific job contexts, they might be used as starting points for quantitative research. Perhaps scales can be developed assessing the degree to which a respondent’s job provides opportunities for the themes identified here. Quantitative research could also be conducted to test for the mediating effects of our themes in the relationship between employment and well-being. Additionally, we should explore how each of these work benefits might interact with individual characteristics. For example, perhaps one needs to possess a certain level of trait altruism in order to derive well-being from opportunities to help others at work.

This research also has implications for policy. Although financial assistance can help people meet their basic needs, it cannot fulfill the higher-order benefits we found to be associated with work, such as autonomy, empowerment, and altruism. Rather, programs aimed at increasing employment, such as job creation, job skills training, and career counselling would be more conducive to beneficiaries’ psychological well-being. Additionally, these programs would probably be shorter term and more cost-effective than pure financial assistance. By increasing the social capital of our population and connecting them to employment opportunities, we can also promote health and well-being. Further, many of the benefits participants discussed were not dependent upon actual income. This suggests that part-time or volunteering opportunities might provide some of the same benefits of work and should be encouraged, even amongst those who are financially stable and would not otherwise seek employment, such as the homemakers, retirees, and the disabled.

Previous findings suggest that the benefits of positive work experiences are enhanced by sharing them with others (i.e. recounting them to family members), a phenomenon known as work-family capitalization (Ilies et al. 2011; Judge and Ilies 2004). Therefore, as a form of daily, self-administered therapy, people might be encouraged to share positive work experiences, such as instances of empowerment and altruism, with family members and friends.

5 Conclusion

Our goal was to understand the psychosocial benefits of work through participants’ own perspectives. Utilizing the flexibility of qualitative data, we uncovered several ways in which work makes genuine contributions to well-being, which have not been documented by the existing body of primarily risk-oriented literature. Moving forward, the research focus no longer needs to be exclusively on how much unemployment hurts, but also on how much employment can help. As the economy recovers and job opportunities emerge, we need establish the importance of returning to work so that people are ready and willing to take advantage of them.

References

Abt SRBI. (2012). Second National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV II): Methods report. Silver Spring, MD: Author.

An, J. S., & Cooney, T. M. (2006). Psychological well-being in mid to late life: The role of generativity development and parent–child relationships across the lifespan. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(5), 410–421.

Ardelt, M., Landes, S. D., & Vaillant, G. E. (2010). The long-term effects of World War II combat exposure on later life well-being moderated by generativity. Research in Human Development, 7(3), 202–220. doi:10.1080/15427609.2010.504505.

Arnetz, B. B., Ventimiglia, M., Beech, P., DeMarinis, V., Lökk, J., & Arnetz, J. E. (2013). Spiritual values and practices in the workplace and employee stress and mental well-being. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 10(3), 271–281.

Bell, M. D., Lysaker, P. H., & Milstein, R. M. (1996). Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 22(1), 51.

Bond, G. R., Resnick, S. G., Drake, R. E., Xie, H., McHugo, G. J., & Bebout, R. R. (2001). Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(3), 489.

Brown, S. P., & Leigh, T. W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 358.

Burns, R. A., Anstey, K. J., & Windsor, T. D. (2011). Subjective well-being mediates the effects of resilience and mastery on depression and anxiety in a large community sample of young and middle-aged adults. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(3), 240–248.

Claussen, B. (1999). Alcohol disorders and re-employment in a 5-year follow-up of long-term unemployed. Addiction, 94(1), 133–138.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. doi:10.1007/bf00988593.

Cox, K. S., Wilt, J., Olson, B., & McAdams, D. P. (2010). Generativity, the Big Five, and psychosocial adaptation in midlife adults. Journal of Personality, 78(4), 1185–1208.

Creed, P. A., Bloxsome, T. D., & Johnston, K. (2001). Self-esteem and self-efficacy outcomes for unemployed individuals attending occupational skills training programs. Community, Work & Family, 4(3), 285–303.

Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work engagement and work-family facilitation: Making homes happier through positive affective spillover. Human Relations, 65(9), 1155–1177.

Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384.

Fischer, R., & Boer, D. (2011). What is more important for national well-being: money or autonomy? A meta-analysis of well-being, burnout, and anxiety across 63 societies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 164.

Frazier, P., Greer, C., Gabrielsen, S., Tennen, H., Park, C., & Tomich, P. (2013). The relation between trauma exposure and prosocial behavior. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(3), 286.

Frech, A., & Damaske, S. (2012). The relationships between mothers’ work pathways and physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 396–412.

Galesic, M., & Bosnjak, M. (2009). Effects of questionnaire length on participation and indicators of response quality in a web survey. Public Opinion Quarterly, 73(2), 349–360.

Grych, J., Hamby, S., & Banyard, V. The resilience portfolio model: Understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychology of Violence (in press).

Hall, J. P., Kurth, N. K., & Hunt, S. L. (2013). Employment as a health determinant for working-age, dually-eligible people with disabilities. Disability and Health Journal, 6(2), 100–106.

Hamby, S., Grych, J., & Banyard, V. (2013). Life paths research measurement packet. Sewanee, TN: Life Paths Research Program.

Hamby, S., Thomas, L., Banyard, V., de St. Aubin, E., & Grych, J. (2015). Generative roles: Assessing sustained involvement in generativity. American Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 24–32.

Hamby, S., Turner, H. A., & Finkelhor, D. (2011). Financial Strain Index. Durham, NH: Crimes Against Children Research Center.

Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 965–983.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2011). Well-being and trust in the workplace. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 747–767.

Henkel, D. (2011). Unemployment and substance use: A review of the literature (1990–2010). Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 4(1), 4–27.

Herbig, B., Dragano, N., & Angerer, P. (2013). Health in the long-term unemployed. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 110(23–24), 413.

Hosie, P., Sevastos, P., & Cooper, C. L. (2007). The ‘happy productive worker thesis’ and Australian managers. Journal of Human Values, 13(2), 151–176.

Ilies, R., Keeney, J., & Scott, B. A. (2011). Work–family interpersonal capitalization: Sharing positive work events at home. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114(2), 115–126.

Jandackova, V. K., Paulik, K., & Steptoe, A. (2012). The impact of unemployment on heart rate variability: The evidence from the Czech Republic. Biological Psychology, 91(2), 238–244.

Jin, R. L., Shah, C. P., & Svoboda, T. J. (1995). The impact of unemployment on health: A review of the evidence. CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association journal, 153(5), 529.

Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2004). Affect and job satisfaction: A study of their relationship at work and at home. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 661.

Kahana, E., Bhatta, T., Lovegreen, L. D., Kahana, B., & Midlarsky, E. (2013). Altruism, helping, and volunteering: Pathways to well-being in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 25(1), 159–187.

Karraker, A. (2014). ‘Feeling poor’: Perceived economic position and environmental mastery among older Americans. Journal of Aging and Health, 26(3), 474–494.

Kyriacou, D. N., Anglin, D., Taliaferro, E., Stone, S., Tubb, T., Linden, J. A., et al. (1999). Risk factors for injury to women from domestic violence. New England Journal of Medicine, 341(25), 1892–1898.

Levecque, K., Lodewyckx, I., & Vranken, J. (2007). Depression and generalised anxiety in the general population in Belgium: A comparison between native and immigrant groups. Journal of Affective Disorders, 97(1), 229–239.

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Steger, M. (2010). Character strengths and well-being among volunteers and employees: Toward an integrative model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(6), 419–430.

Liu, A. M., Chiu, W., & Fellows, R. (2007). Enhancing commitment through work empowerment. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 14(6), 568–580.

Luo, J., Qu, Z., Rockett, I., & Zhang, X. (2010). Employment status and self-rated health in north-western China. Public health, 124(3), 174–179.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

Mattiasson, I., Lindgärde, F., Nilsson, J. A., & Theorell, T. (1990). Threat of unemployment and cardiovascular risk factors: Longitudinal study of quality of sleep and serum cholesterol concentrations in men threatened with redundancy. BMJ. British Medical Journal, 301(6750), 461.

McAdams, D. P., & De St Aubin, E. (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(6), 1003.

McKee, M. C., Driscoll, C., Kelloway, E. K., & Kelley, E. (2011). Exploring linkages among transformational leadership, workplace spirituality and well-being in health care workers. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 8(3), 233–255.

Montgomery, S. M., Cook, D. G., Bartley, M. J., & Wadsworth, M. E. (1998). Unemployment, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and body weight in young British men. The European Journal of Public Health, 8(1), 21–27.

Nandi, A., Charters, T. J., Strumpf, E. C., Heymann, J., & Harper, S. (2013). Economic conditions and health behaviours during the ‘Great Recession’. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(12), 1038–1046.

Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Demerouti, E., & Bakker, A. B. (2014). Engaged at work and happy at home: A spillover–Crossover model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(2), 271–283.

Roelfs, D. J., Shor, E., Davidson, K. W., & Schwartz, J. E. (2011). Losing life and livelihood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of unemployment and all-cause mortality. Social Science and Medicine, 72(6), 840–854.

Rosenthal, L., Carroll-Scott, A., Earnshaw, V. A., Santilli, A., & Ickovics, J. R. (2012). The importance of full-time work for urban adults’ mental and physical health. Social Science and Medicine, 75(9), 1692–1696.

Rothmann, S., & Essenko, N. (2007). Job characteristics, optimism, burnout, and ill health of support staff in a higher education institution in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 37(1), 135–152.

Rueda, S., Chambers, L., Wilson, M., Mustard, C., Rourke, S. B., Bayoumi, A., et al. (2012). Association of returning to work with better health in working-aged adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 541–556.

Rueda, S., Raboud, J., Mustard, C., Bayoumi, A., Lavis, J. N., & Rourke, S. B. (2011). Employment status is associated with both physical and mental health quality of life in people living with HIV. AIDS care, 23(4), 435–443.

Russell, H. (1999). Friends in low places: Gender, unemployment and sociability. Work, Employment & Society, 13(2), 205–224.

Russell, M., Harris, B., & Gockel, A. (2008). Parenting in poverty: Perspectives of high-risk parents. Journal of children and poverty, 14(1), 83–98.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being, 9(1), 13–39.

Shuck, B., & Reio, T. G. (2014). Employee engagement and well-being a moderation model and implications for practice. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(1), 43–58.

Stansfeld, S. A., Shipley, M. J., Head, J., Fuhrer, R., & Kivimaki, M. (2013). Work characteristics and personal social support as determinants of subjective well-being. PLoS ONE, 8(11), e81115.

Stöckl, H., Heise, L., & Watts, C. (2011). Factors associated with violence by a current partner in a nationally representative sample of German women. Sociology of Health & Illness, 33(5), 694–709.

Stuckler, D., Basu, S., Suhrcke, M., & McKee, M. (2009). The health implications of financial crisis: A review of the evidence. The Ulster medical journal, 78(3), 142.

Timperi, A. W., Ergas, I. J., Rehkopf, D. H., Roh, J. M., Kwan, M. L., & Kushi, L. H. (2013). Employment status and quality of life in recently diagnosed breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 22(6), 1411–1420.

Umberson, D., Pudrovska, T., & Reczek, C. (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective. Journal of Marriage & Family, 72(3), 612–629. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00721.x.

U.S. Air Force. (2011). 2011 Air Force Community Assessment Survey: Survey data codebook. Lackland Air Force Base, TX: U.S. Air Force.

Van Dongen, C. J. (1996). Quality of life and self-esteem in working and nonworking persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 32(6), 535–548.

Walker, D., & Myrick, F. (2006). Grounded theory: An exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 547–559.

Weber, A., & Lehnert, G. (1997). Unemployment and cardiovascular diseases: A causal relationship? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 70(3), 153–160.

Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244.

Yuŕyev, A., Värnik, A., Värnik, P., Sisask, M., & Leppik, L. (2012). Employment status influences suicide mortality in Europe. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(1), 62–68.

Zabkiewicz, D. (2010). The mental health benefits of work: Do they apply to poor single mothers? Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(1), 77–87.

Zeng, Q. (2012). Youth unemployment and the risk of social relationship exclusion: A qualitative study in a Chinese context. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 17(2–3), 85–94.

Zhan, Y., Wang, M., Liu, S., & Shultz, K. S. (2009). Bridge employment and retirees’ health: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(4), 374.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hagler, M., Hamby, S., Grych, J. et al. Working for Well-Being: Uncovering the Protective Benefits of Work Through Mixed Methods Analysis. J Happiness Stud 17, 1493–1510 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9654-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9654-4