Abstract

This paper uses life satisfaction regressions based on three surveys in two countries (Canada and the United States) to estimate the relative values of financial and non-financial job characteristics. The well-being results show strikingly large values for non-financial job characteristics, especially workplace trust and other measures of the quality of social capital in workplaces. For example, an increase of trust in management that is about one tenth of the scale has a value in terms of life satisfaction equivalent to an increase of more than 30% in monetary income. We find that these values differ significantly by gender and by union status. We consider the reasons for such large values, and explore their implications for employers, employees, and policy-makers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Well-Being and the Workplace: Setting the Stage

Much of the recent empirical and theoretical analysis of social capital (e.g. Putnam 2000; Helliwell and Putnam 2004) has concentrated on interactions in families and communities, with only limited attention paid to the nature and consequences of social capital in the workplace. Since that earlier research showed the great importance of social capital to subjective well-being, it seemed likely that it would also be worthwhile to collect evidence about social capital in the workplace, given the large fraction of waking hours spent there. In this paper we present results based on three surveys from Canada and the United States, focusing on those who held paid jobs at the time of the survey.

We estimate and report here estimates of the values of various aspects of life on the job, measured as ‘compensating differentials’. The basic idea is fairly simple. Measures of life satisfaction (or of happiness in the case of the US Benchmark survey) are used as dependent variables, with the independent variables including those variables thought to have important implications for life satisfaction. If the influence of income on life satisfaction is significant, then the income-equivalent values of other significant determinants can be measured as the size of the change in income that would have the same well-being effect as a given change in the other variable of interest.

The estimates of compensating differentials for non-financial job characteristics, and especially of workplace trust, are strikingly large. For example, results from one of the Canadian surveys used in the paper suggest that having a job in a workplace where trust in management is ranked 1 point higher on a 10-point scale has the equivalent effect on life satisfaction as a more than 30% increase in income. In this paper we attempt to explain why union workers are as satisfied with life as non-union workers, despite working in environments where they judge management to be less trustworthy. Second, we look for, and find, interesting gender differences in the ways in which male and female workers choose and evaluate their workplaces. We were inspired to do this by Fortin’s analysis (Fortin 2005, based on World Values Survey data) suggesting that some important part of the male–female earning gap might be based on deliberate choices by female workers favouring jobs with lower income and better working conditions. If her conjectures are more generally applicable, they would suggest that female workers attach higher life-satisfaction value to non-financial job characteristics than do males, and that they might therefore take jobs with higher values of trust and other non-financial job characteristics, but with lower earnings. In one Canadian survey that has detailed workplace information, there is at least some initial support for this interpretation, as female employees rate trust in management at their workplaces higher than do men, with the gender difference being the same whether the employees are union members or not. This is not simply due to women being more trusting than men, as there is no significant gender difference in social trust, trust in police, or trust in neighbours. If we find significant male/female differences in relative preferences for income and non-financial job characteristics, then this might help to explain, following Fortin’s conjectures, some part of the remaining earnings gap between genders. Previous work on gender differences in job satisfaction by Clark (1997), finds that female workers in the British Household Panel Survey rank workplace social relations more highly than do men, while men rank promotion prospects, pay and job security more highly than do women. Here we focus on the trust aspects of work-place relations.

2 Using Life Satisfaction Data to Value Workplace Social Capital

We are going to use ‘compensating differentials’ to measure the values of workplace social capital. There have been many previous attempts in the literature to value non-financial aspects of jobs using wages or incomes as the dependent variable. Many are based on cross-sectional studies using data at the level of individual workers. There are econometric problems in this approach caused by the problem of unobservable ability.

Consider an estimation equation with earnings on the left-hand side as the dependent variable:

where y i is the earnings level for worker i, X i is a vector of job characteristics, applicable to worker i’s job, with compensating differentials estimated by the coefficient vector β. The Z i are measured characteristics of worker i. The error term has two parts. ε i is the idiosyncratic term related to the skill level of worker i, and Zu i are other unmeasured characteristics of the worker, the job, or the market environment in which the wage is being paid.

We can start from a worker’s theoretical optimization problem and show that the unobserved ability affects both the earnings of the worker and the characteristics of the chosen job. The problem is well known in the literature (e.g. Hwang et al. 1992). The worker solves:

where U(.,.) is the utility function. The two arguments are income and non-financial job attributes in that order. Positive elements in the vector of job attributes X i enhance utility, and vice versa. We assume that jobs differ in their characteristics and that employees can choose between a more interesting or engaging job with a lower wage and a less pleasant environment with a higher wage. The labour market is presumed to offer potential workers many different packages, with prices of job attributes as denoted by the vector β. The budget constraint requires that the money wage and the cost (or benefit if negative) of the chosen job attributes should sum to the total earning potential of the worker, denoted as ω i .

The solution to this maximization has to satisfy the following three-equation system including the first order condition for chosen wage, the first order condition for the chosen job attributes, and the budget constraint, respectively written:

where λ i is the Lagrangian multiplier.

A solution of this system gives optimal choice of y i and X i , both of which are functions of the compensating differentials β, and the unobservable skill level ω i

By substituting the optimal choices back into the budget constraint and moving the wage to the left hand side, we have the relation between wage and job attributes in the equilibrium that is underlying Eq. 1:

With cross-sectional data, the unobservable earning potential ωi becomes part of the error term, thus leaving the error term correlated with both the dependent wage variable and the job characteristics used as independent variables. The estimation of β will thus be biased downward. For instance, suppose that job safety is included among the X variables. With the usual theoretical presumption that safety is a normal good, workers possessing higher than average abilities use their extra bargaining power to obtain jobs that are both safer and more highly paid. In the absence of a variable measuring ability, this behaviour would lead to an upward bias on the coefficient measuring the effects of education (assuming ability and education to be positive correlated) and a bias towards zero on the coefficients of variables measuring job safety. In the absence of variables measuring worker education and training, the downward bias in the estimation of the compensating variation for safety would probably be even greater.

Data from one of the surveys used in this paper can be used to illustrate the reality of this problem, and show also that attempts to remove the bias in the estimation of compensating differentials by allowing for the effects of education on income are likely to be insufficient. In the Canadian Equality, Security, and Community survey, for example, working respondents are asked to measure the extent to which their jobs possess five job characteristics and one workplace characteristic that are presumed (and subsequently found) to have a positive influence on job satisfaction, independent of the level of income. Each respondent is asked whether their job: allows them to make a lot of decisions on their own, requires a high level of skill, has a variety of tasks, provides enough time to get the job done, and is free of conflicting demands. The answers are given on a four-point scale, converted to a 0–1 scale for the analysis presented below. Respondents are also asked, this time on a scale of 1–10, to rate the level of trust that workers have in management at their workplace. Of these six factors, three have positive correlations with income (decision scope, skill and variety), while the other three have negative correlations. This pattern holds whether the correlations with income are measured individually or jointly, and occur whether or not the substantial effects of education on income are allowed for in the way depicted by Eq. 1.Footnote 1

The econometric difficulties posed by using wage equations to identify compensating differentials suggest that it might be more promising to use subjective well-being data as a direct measure of utility, thereby permitting compensating differentials to be estimated as ratios of coefficients estimating the well-being effects of income and job characteristics. We do this by combining Eqs. 2 and 3, the two first-order conditions of the worker’s maximization problem. Noting that the compensating differentials, β, are simply the ratios of the marginal utilities of job attributes over the marginal utility of income, i.e.,

The main challenge in implementing this strategy is to have utility measured in a meaningful way so that the marginal contributions of income and job characteristics can be estimated. This is precisely where our dataset fits in. Each of the three surveys we use includes a question that asks respondents to report their satisfaction with life. We suggest that this measure of life satisfaction, subject to some issues we shall deal with later, can be used as a direct measure of utility. The measurement of utility permits the estimation of marginal utilities, and hence of compensating differentials. This approach avoids the difficulties posed by unobserved skills, since theoretically all utility-maximizing individuals, of whatever level of ability, will set the ratio of marginal utilities to the prevailing market price.

More precisely, our proposed approach is to estimate the marginal contributions of job characteristics and income to life satisfaction, and to calculate compensating differentials directly from these estimated coefficients, as ratios of the job characteristics’ coefficients to the coefficient on the (log of) income. To the extent that jobs are actually available with the characteristics in question, these ratios reflect the prevailing market prices of job attributes, usually described as compensating differentials. Essentially the same approach has been applied by Van Praag and Baarsma (2005) to estimate compensating differentials for aircraft noise in the neighbourhoods surrounding Amsterdam Airport, and by Frey and Stutzer (2004) to value commuting time.

In its general form, the proposed strategy is described by

where LS is the mnemonic for life satisfaction, Φ y (y) is the functional form on income, Φ x (X) is the functional form for job attributes, and Z i are all other controls. These functional forms accommodate a concave utility. In the case of income, we measure it in its log form instead of its level to reflect standard economic assumptions and many empirical results suggesting that less affluent agents derive greater utility from extra income. Therefore Φ y (y) = log(y). For job attributes we adopt a simplistic view that their per unit contribution to workers is the same regardless of income or level of X, so that Φ x (X i ) = X i . Finally we use Z i to control for many observed heterogeneities across agents, including, in some tests, personality differences.

We take into account the functional form in expressing compensating differentials. For instance, in our empirically preferred case where income is in log form and X is in linear form, β will be the log change in income (we convert to percentage changes in our key tables of results) that has for the average employee the same life satisfaction effect as a change in the non-financial job characteristic X.

There is a closely related literature using job quit data to study and compare the effects of income and other aspects of employment. If the models contain income and actual job characteristics as independent variables, they can be used to estimate compensating differentials directly as ratios of coefficients. Bonhomme and Jolivet (2009) and Villanueva (2007) did just this, and since their results, like ours, show high compensating differentials for non-financial job characteristics, they help to support ours in two ways. First, they use behavioral data rather than subjective assessments as dependent variables. Consistency of compensating differentials derived from two quite different dependent variables thus provides mutual confirmation. Second, the use of quits as a dependent variable highlights the importance of information and job change costs as reasons why compensating differentials can be as high as these researchers and we have found. Other job quit studies are slightly less closely related to ours, but relevant nonetheless. Clark (2001) used job quit data to compare the effects of actual pay levels with various aspects of job satisfaction. Finding that several aspects of non-financial job satisfaction are as important as income, and sometimes more important, he argued that economists should therefore treat subjective measures of job satisfaction as having objective importance in the prediction of job changes.

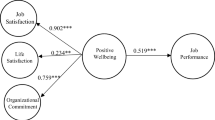

The above papers, as well as Böckerman and Ilmakunnas (2009) and Corneliben (2009), all use job satisfaction as their measure of subjective well-being. By contrast, in this paper we use life satisfaction. We do this because life satisfaction has better claims than job satisfaction to be an overall measure of utility, and therefore should be preferred for the calculation of the overall importance of job characteristics. Helliwell and Huang (2010) demonstrated that there are indeed differences between using life satisfaction and job satisfaction to estimate the subjective well-being effects of job characteristics. It compared the reduced-form life-satisfaction effects of job characteristics with those obtained by first estimating the effects of job characteristics on job satisfaction, and then calculated their effects on life satisfaction as mediated through the estimated effect of job satisfaction on life satisfaction. These two procedures are not expected to give the same answers, since they are measuring interestingly different things. The biggest difference relates to the consequences for well-being of having a job involving lots of decision-making. Decision-making has a significantly positive effect on job satisfaction, but in the reduced form the net effect is insignificantly negative. Thus the gains on the job are offset by losses on the home front. The reverse is true for skill, variety, time available, and freedom from conflicting demands, all of which have greater effects in the reduced-form life satisfaction equation than where their impact is limited to that flowing through job satisfaction. This suggests positive spillovers from these job characteristics, in contrast to the negative ones from decision-making.

3 Data and Empirical Implementation

Our three survey sources include the second wave (2002–2003) of the SSHRC-supported Equality, Security, and Community survey (ESC hereafter, and described in more detail in Soroka et al. 2006), the Statistics Canada 2003 General Social Survey (GSS) and the 2001 US Social Capital Benchmark Survey. The surveys differ in their sample size and the nature and number of questions asked. For the results reported in this paper, we generally restrict our analysis to the working population, roughly 2,500 for the second wave of the ESC, 9,000 for the GSS, and 13,000 for the US Benchmark. The same life satisfaction question is asked in both Canadian surveys: “In general, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days, on a scale of 1–10.” The Benchmark survey asks about the respondent’s happiness, on a 4-point scale. The difference in the scales of the dependent variables has no effect on the ratios of coefficients, and it is these ratios of coefficients that provide the raw material for our calculation of compensating differentials. Life satisfaction questions tend to elicit answers that are more reflective of life circumstances, and less reflective of ephemeral events, than do happiness questions. However, where World Values Survey answers to both questions are compared, the same broad pattern of results appears, thus enabling us in this paper to compare at least roughly the US and Canadian effects of workplace trust.

Equation 4 is designed to estimate compensating differentials for specific job characteristics.

In this equation, LS i is life satisfaction (or happiness in the case of the US Benchmark Survey) for respondent i, measured on a scale of 1–10, y i is the level of income of the respondent’s household (personal income in ESC), and the other variables are as in Eq. 1, except that the coefficients now measure their impact on life satisfaction rather than on wages, and the variable set is expanded to include all other determinants of life satisfaction. When we use Eq. 4 to estimate the value of job characteristics, we will do so by taking the ratio of a coefficient of one of the components of the job characteristic vector X to δ, the coefficient on log income. This matches the functional form assumptions implicit in most previous attempts to evaluate job characteristics using wage equations. It presumes that for each worker the monetary value of a change in some job characteristic is measured as a fraction of his or her income, which in turn implies that higher-income households are prepared to give up more dollars to obtain a higher level of non-financial job satisfaction. This simple form performs well against more complex alternatives. In any event, all of the versions we have considered give us similar basic results.

We try to control for as many as possible of the direct determinants of utility, so that our estimates of the effects of income and workplace characteristics should be relatively accurate, and hence useful for constructing estimates of the income-equivalent values of various elements of workplace social capital. These control variables include gender, age, and marital status, as well as level of education, immigration and ethnic information. They also include a measure of self perceived health status (scale 1–5, with 5 representing the best of health), which we believe not only controls for physical health, but also psychological health and some unobserved personality differences.Footnote 2 Furthermore, we have information from all three surveys about the respondent’s frequency of contacts with family members outside the household, with friends, and with neighbours, and also the number of memberships (or extent of activity) in voluntary organizations. These measures are all scaled between zero and one, although they are not defined in the same way across all three surveys, so their coefficients are not strictly comparable across surveys. But they all serve the same purpose, which is to control for factors that are likely to affect life satisfaction, thereby making the coefficients on income and jobs as comparable as possible across the three surveys. We use survey-ordered probit estimation with errors presumed to be clustered at the level of the census tract, or community in the case of US Benchmark survey, to allow for omitted community-level determinants of life satisfaction. Although the probit and linear forms give similar results for compensating differentials, the probit form permits us to drop the cardinality assumption required by the linear form.

The ESC, GSS and Benchmark surveys all contain some measure or measures of workplace trust. The ESC asks about the extent to which management can be trusted in the respondent’s workplace, while the GSS and Benchmark surveys ask to what extent there is trust among colleagues. Figure 1 shows a cross-tabulation of trust in management and life satisfaction for all employed respondents in the second wave of the ESC survey. The figure shows both that trust in management is generally high among the ESC respondents (6.7 on a ten-point scale—see Appendix) and that life satisfaction is significantly higher among those who work where they rank management trustworthiness highly. For example, the roughly one-quarter of paid workers who rate trust in management at 9 or 10 on a ten point scale report life satisfaction of 8.3 on a ten-point scale, compared to an average of 7.5 for the slightly larger number of workers who rate trust in management at 5 or below.

4 Basic Results

The basic well-being equations are shown in Table 1, with the ESC in column 1, the GSS in column 2, and the US Benchmark in column 3. The corresponding ESC estimates of compensating differentials for workplace trust are shown in the first column of Table 3. Among the estimates the focus is on various measures of trusts. The social capital literature (see Halpern 2005 for a review) gives a central place to trust, with high levels of trust being positively related to other measures of social capital (and sometimes being used themselves as either proxy or direct measures of social capital), with causation likely to flow both ways (Putnam 2000). The well-being equations in this paper suggest that several different sorts of trust have direct effects on well-being, particularly so for domain-specific trust.

The calculated compensating differentials (and their standard errors) for workplace trust are shown in the first column of Table 3. The compensating differentials are large in magnitude and in statistical significance. For the whole sample of workers, a change in trust in management of just one-third of a standard deviation (about 0.7 points on the 10-point scale, covering about 10% of the sample) has the same life satisfaction effect as a 31% change in income (with a t value of 4.5). The coefficients from the GSS and the US Benchmark survey, shown in Table 1, imply compensating differentials for trust in co-workers in the Benchmark that are very similar to those for trust in management in the ESC, while the effects are even larger for the GSS, driven by a significantly smaller income effect in the GSS than in the ESC.

Table 2 focuses on the ESC survey. Its second column presents results from an augmented life satisfaction equation that includes various aspects of workplace life other than workplace trust. The first column repeats the earlier result from the basic equation for side-by-side comparison. With the new variables, the coefficient on workplace trust drops from 0.185–0.16. The coefficient on income drops slightly more, in proportionate terms. As the result, the estimated compensating differential rises. As for the newly added workplace variables, jobs that require skill, have variety, have sufficient time available for completion, and are free of conflicting demands are associated with significantly higher life satisfaction, while those that involve a lot of decision-making do not increase life satisfaction. Jobs that involve a lot of decision-making are associated with higher levels of job satisfaction, but these are lost in the conversion to life as a whole, presumably because of offsetting stresses on the home front.

In the following sections of this paper, we analyze the relation between trust in management and life satisfaction disaggregated by the union status and gender, since these are two dimensions on which we find significant differences in the observed pattern of relations between workplace trust and well-being.

5 Workplace Trust and Union Status

Figure 2 shows how trust in management differs as between union and non-union workers in the ESC sample, while Appendix shows the means and standard deviations of the data. Figure 2 shows that union workers are less likely to place high level of trust in management than are non-union workers. The Appendix shows that union members (about one-third of the sample, reflecting the current national average) rate trust in management, on average, at just under 6.0 on a ten-point scale, compared to 7.1 for the non-union workers. This is not because union workers are generally either an unhappy or a non-trusting lot, as their average life satisfaction is just as high as that of non-union workers, while their general social trust, trust in neighbours and trust in police are equal to or higher than those of non-union workers, as shown in Fig. 3.

The causal interpretation on the observed correlation between union status and workplace trust is less than settled. On the one hand, low-trust workplaces are likely to have more dissatisfied workers, and to provide a climate more open to establishment of a bargaining unit. On the other hand, the climate of management-employee relations may be exacerbated in a union environment, since at least some of the company and union representatives have the maintenance of adversarial relations as an essential part of their jobs. To the extent this is true, one might expect to find that the lower trust in management found among union workers is not matched by low trust among colleagues. Although we do not yet have surveys asking about both trust in management and trust among colleagues, we do find that in the US Benchmark survey there is no difference between union and non-union workers in the extent to which they feel trust in their fellow workers. This suggests that there is a special link between trust in management and unionization, with the correlation perhaps reflecting causation running in both directions. A related finding in the literature is the observation that union members report lower job satisfaction than non-union workers (Bryson et al. 2004, and the references within). The IV estimation in Bryson et al. (2004) finds evidences favoring an interpretation based on endogenous selection as opposed to a causal one. Providing causal interpretation for the relation between union and employer-employee trust could be an interesting research for improving our understanding of the role of unions in workplaces. Unfortunately, in the data we use, there is no obvious choice for a credible instrument.Footnote 3

This paper’s interest is in the relation between workplace trust and life satisfaction. Figure 4 plots average life satisfaction against perceived trust in management, separately for union and non-union workers. It shows that the higher well-being associated with being in a job where trust in management is more beneficial for non-union than for union workers, as shown by the steeper slope. In addition, as would be suggested by the previous paragraph, when the respondents are sorted according to their answers to the question about trust in management, union workers are on average more satisfied with their lives than are non-union workers. This follows from the facts already noted, that the two groups of workers are on average about equally happy, while the union workers rate trust in management lower than do non-union workers.

Regression analysis confirms the observation from the raw data. Table 3 shows the estimated compensating differentials for trust in management for union and non-union workers, respectively. The underlying coefficients come from split-sample estimation by union status presented in the third and the fourth columns of Table 2. For non-union workers, the estimated compensating differentials are twice as high as they are for those who are unionized.

The lower compensating differentials detected for unionized workers probably reflect some element of sorting, with those less bothered by a low-trust working environment taking union jobs with their related combination of higher pay and lower trust in management. But it may also mean that unions are doing their jobs, in the sense that they have negotiated contracts and grievance procedures to protect their members against at least some of the risks of working where management is not trusted by workers. This may help to explain why union workers are as satisfied with their lives as non-union workers despite their lower trust in management (Appendix).

6 Gender Differences: Trust Matters More for Females

The difference between union and non-union workers is mirrored by that between male and female workers, with females, like non-union workers, being more likely to be working in jobs where trust in management is rated higher (Fig. 5), and apparently gaining more (in terms of higher life satisfaction) from working in a high-trust environment (Fig. 6). This is not simply the same phenomenon with a different name, because in the ESC sample, and in the Canadian economy as a whole, the percent of females working in union jobs is almost exactly the same as for males. The lack of interaction effects (tested for, and found to be absent) suggests that the two situations are sufficiently independent to be analyzed separately.

The magnitudes of the male/female and the union/non-union differences in the estimated values attached to trust in management are strikingly similar. Table 3 shows the estimated compensating differentials by gender; the underlying coefficient estimates are shown in the last two columns of Table 2. These estimates show that female workers attach income-equivalent life satisfaction values for trust in management that are twice as high as for male workers. This is exactly as was found when we compared non-union and union workers. In both cases the differences in compensating differentials result from females, and non-union workers, attaching a lower value to income and a higher value to trust in management than do male or union workers. For women, as compared to non-union workers, more of the effect flows through the income coefficients, and less through trust in management, but these differences are too small to be significant. Gender, unlike union status, is exogenous. The interpretation is thus not complicated by sorting effects, which complicated our analysis of union membership. The gender differences detected in this paper are consistent with Clark (1997), where female workers in the UK ranked workplace relations more highly than did men. Since trust is a prerequisite condition for good relations, our results and those of Clark appear to be mutually confirming. By using life satisfaction data, we are able to extend the evaluation from job satisfaction to overall life satisfaction. As we have already shown, the preference results for job satisfaction cannot be automatically assumed to apply similarly to life satisfaction.

As noted in the first section of the paper, Fortin (2005) has already found some evidence in OECD countries that women are more likely to value jobs that have lower pay and more flexible working conditions. This appears to be entirely consistent with our findings, as workplaces where trust in management is high are workplaces where flexible working arrangements are more likely to be in place and working smoothly. Informal interviews with female workers in high trust jobs, many of which offered lower pay but higher trust than previous jobs, showed that a large part of the value of the high-trust environment lay in the ease with which flexible working arrangements, including several features of child-rearing, could be obtained without fear or hassle. It is also possible that there are more basic gender differences in the values attached to working in jobs with high levels of trust. Our current results do not allow us to distinguish the relative importance of gender-based personality differences and gender-based differences in life circumstances.

In the meantime, our results do suggest that at least some part of the male/female gap in money wages is offset for females by working in high-trust jobs. Thus we find, as shown in Appendix, that although female workers in our sample earn less per hour worked, they have equal or greater satisfaction with their jobs and their lives, and are in jobs where trust in management is rated more highly. It is possible to use our coefficient estimates to calculate what fraction of the hourly earnings difference between males and females might be compensated for by the difference in trust in management. Using the compensating differentials in Table 3, as seen from a female perspective, the higher average assessments of trust in management in the jobs held by females have a life satisfaction effect almost two-fifths as large as those attributable to the higher average hourly earnings of males compared to females in our ESC sample.Footnote 4

7 Conclusion

The estimated values of trust in the workplace are very large, and remain so even when we make a number of adjustments designed to remove risks of over-estimation. Our workplace trust results are independently estimated from two Canadian and one US survey using different samples and different question wordings. That all three surveys should show such consistently large effects convinces us of the robustness of our results.

There is much more to be done, in collecting fresh samples of data and especially in developing survey sources that will provide data linking individual subjective assessments of workplace quality and life satisfaction with workplace-based information about the structure of specific places of employment. We think that the strength and consistency of our results to date is sufficient to support more research in these directions. Perhaps it may already be enough to convince workers and managers to pay more attention to workplace trust,Footnote 5 since it seems central to life satisfaction, and may otherwise be inadvertently risked by workplace changes undertaken for other reasons.

More generally, our workplace results can be seen as part of a move towards using measures of subjective well-being to estimate the relative importance of income and other aspects of life at work, in the home, in the community, and across nations. The accumulating results showing the high values attached to the social context have implications for how firms, communities and nations might be better managed.

Notes

If a version of Eq. 1 is estimated using all six job characteristics and three education level variables, the sign patterns are as described in the text. Of the ‘correctly’ (negatively) signed job characteristics, “free of conflicting demands” is insignificant.

As pointed out by a referee, health status is a highly endogenous variable. Our purpose for including it is two-fold: to account separately for the importance of subjective health as a determinant of life satisfaction, and to help control for possible interpersonal differences in optimism. Excluding the health variable from the regression raises the coefficients on income and on job satisfaction slightly. But the ratio between the two is little changed. In the case of ESC full-sample estimation in column 1 of Table 1, the ratio changes from 0.93 with the health variable included to 0.94 without.

An instrument variable ideally will incorporate external information other than an individual worker’s own responses to survey questions to avoid endogeneity. In the case of Bryson et al. (2004), such external information is managers’ evaluations of industrial relations in the establishments where respondents are employed. Our surveys provide little external information.

In the fourth column of Table 2, which has the regression result for female workers, the coefficient on the standardized trust in management is 1.25 times as large as the coefficient on the log of personal income. This implies that we can multiply the difference in standardized trust by 1.25 to turn it into income-equivalent units. The gender difference in the average assessment of trust in management is 0.13, with females being higher. The difference amounts to 0.057 standardized units. The corresponding income-equivalent value is therefore 0.057 × 1.25 = 0.071. The gender difference in personal income per hour of work is 0.19, with females being lower. Therefore the difference in workplace trust contributes almost two-fifths (0.071/0.19 = 0.37) of the gender difference in hourly earnings.

There has been increasing interest in the topic within the human resources research community. For example, a 2003 special issue of the International Journal of Human Resource Management was devoted to workplace trust. See Ziffane and Connell (2003). For a survey of some of the related research in psychology, see Kramer (1999).

References

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2009). Job disamenities, job satisfaction, quit intentions, and actual separations: Putting the pieces together. Industrial Relations, 48(1), 73–96.

Bonhomme, S., & Jolivet, G. (2009). The pervasive absence of compensating differentials. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 24(5), 763–795.

Bryson, A., Cappellari, L., & Lucifora, C. (2004). Does union membership really reduce job satisfaction? British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42(3), 439–459.

Clark, A. E. (1997). Job satisfaction and gender: Why are women so happy at work? Labour Economics, 4, 341–372.

Clark, A. E. (2001). What really matters in a job? Hedonic measurement using quit data. Labour Economics, 8(2), 223–242.

Corneliben, T. (2009). The interaction of job satisfaction, job search, and job changes. An empirical investigation with German panel data. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 367–384.

Fortin, N. (2005). Gender role attitudes and the labour market outcomes of women across OECD countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21(3), 416–438.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2004). Economic consequences of mispredicting utility. Working paper 218. University of Zurich: Institute for Empirical Research in Economics.

Halpern, D. (2005). Social capital. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2010). How’s the job? Well-being and social capital in the workplace. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 63(2), 205–227.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B 359: 1435–1446. Reprinted in F. A. Huppert, B. Kaverne & N. Baylis (Eds.) (2005) The science of well-being (pp. 435–459). London: Oxford University Press.

Hwang, H.-S., Reed, W. R., & Hubbard, C. (1992). Compensating wage differentials and unobserved productivity. Journal of Political Economy, 100(4), 835–858.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Soroka, S., Helliwell, J. F., & Johnston, R. (2006). Measuring and modelling interpersonal trust. In Kay. Fiona & Johnston. Richard (Eds.), Diversity, social capital and the welfare state (pp. 95–132). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Van Praag, B. M. S., & Baarsma, B. E. (2005). Using happiness surveys to value intangibles: The case of aircraft noise. Economic Journal, 115, 224–246.

Villanueva, E. (2007). Compensating wage differentials and voluntary job changes: Evidence from Germany. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 60(4), 544–561.

Ziffane, R., & Connell, J. (2003). Trust and HRM in the new millennium. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(1), 3–11.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Helliwell, J.F., Huang, H. Well-Being and Trust in the Workplace. J Happiness Stud 12, 747–767 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9225-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9225-7