Abstract

The current diary study among 50 Spanish dual-earner couples examines whether engagement at work has an impact on own and partners’ well-being. Based on the Spillover–Crossover model, we hypothesized that individuals’ work engagement would spill over to the home domain, increasing their happiness level at the end of the day. Moreover, we predicted a crossover of happiness between the members of the couple. Participants filled in a diary booklet during five consecutive working days (N = 100 participants and N = 500 occasions). The results of multilevel analyses showed that daily work engagement has a direct effect on daily happiness. We also found that employees’ daily work engagement influenced partner’s daily happiness through employees’ daily happiness. Finally, results showed a clear bidirectional crossover of daily happiness between both members of the couple. These findings indicate that the positive effects of work engagement go beyond the work setting and beyond the employee.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Employee work engagement has been defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002). The concept of work engagement has traditionally been linked to various indicators of occupational well-being such as job satisfaction, involvement, and reduced burnout (Bakker et al. 2008), as well as objective performance (Xanthopoulou et al. 2009). Moreover, the majority of studies on work engagement focuses on work-related outcomes, rather than on potential benefits for employees’ private life. However, during the last years, researchers examining the relationships between work and non-work domains have raised new questions around the concept of engagement, such as its relationship with recovery during leisure time or its impact on colleagues and family. For instance, in a daily diary study, Sonnentag et al. (2008) found that on days employees showed high levels of work engagement, they were better able to detach from their work during the evening. In the work setting, there is evidence showing that work engagement is transmitted between colleagues on a daily basis (Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009). In research among spouses, it has been shown that work engagement is not only important for one’s own performance, but also for one’s partner’s performance (Bakker and Demerouti 2009).

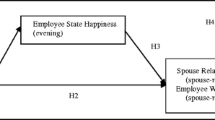

In the present study, we are interested in examining two processes linking work experiences and well-being on a daily basis, namely spillover and crossover. Whereas spillover refers to the transmission of experiences between domains (i.e., from work to home), crossover refers to transmission within the same domain (Bakker and Demerouti 2013). The Spillover–Crossover Model (SCM) proposed by the latter authors brings together employees’ main life domains: work and family. Accordingly, employees’ work experiences impact behaviors, thoughts and feelings in the home domain, which in turn, are transmitted to the partner. Studies analyzing negative experiences such as work-family conflict (Shimazu et al. 2009), and workaholism (Bakker et al. 2009) have provided support for the SCM model. Recently, Demerouti (2012) showed that the SCM also applies to positive experiences of energy and motivation. We continue this line of research by focusing on the positive side by examining first how daily work engagement spills over to the home domain resulting in higher daily happiness, and second, how daily happiness crosses over from employees to their partner. Thus, we propose an indirect effect of employees’ daily work engagement on partners’ daily happiness.

This study contributes to the literature on engagement and happiness in several ways. First, we add to the few studies in the field examining work engagement on a daily basis. It has been shown that engagement is not as stable as researchers assumed originally, and it is possible to observe day-to-day fluctuations on the levels of vigor, dedication, and absorption (Breevaart et al. 2012). Second, although the effects of engagement have been analyzed before, their impact on subjective well-being and in particular on happiness has not been previously assessed. Third, although Demerouti et al. (2005) examined bidirectional crossover of life satisfaction among couples, this is the first study to examine the bidirectional crossover of happiness between working couples on a daily basis. We aim at gaining insight in the daily spillover of engagement in terms of happiness, and how it may be transmitted to the partner. There is a lack of studies examining how work engagement may affect employees’ significant others (Bakker and Demerouti 2009). Fourth, we used an innovative strategy of analysis, called the actor-partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny et al. 2008). By using this method, it is possible to examine (a) how work experiences affect both own and partner’s well-being, and (b) mutual effects between the members of the dyad.

1.1 The Daily Spillover of Work Engagement

As mentioned above, work engagement is considered as a work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al. 2002). Vigor is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience while working. Dedication refers to the sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride and challenge. Absorption is characterized by being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in one’s work, whereby time passes quickly (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). When the concept was emerging, engagement was considered as a relatively stable experience—a persistent and pervasive state rather than a momentary state (Schaufeli et al. 2002; see also, Macey and Schneider 2008).

Lately, innovative designs such as diary studies have allowed scholars to explore within-person variations during short-term periods, such as episodes during the day, across days, or across weeks. This type of design offers a more dynamic view of the everyday experiences of working individuals (Ohly et al. 2010). In the case of work engagement, previous daily studies show that the variance attributable to within-person fluctuations ranges from 44 to 72 %, which means that this positive work experience varies significantly from 1 day to another (Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009; Tims et al. 2011). For this reason, the concept of engagement has been lately redefined, considering it as a transient instead of stable work-related experience that may fluctuate within individuals (Sonnentag et al. 2010).

Most diary studies have linked work engagement to work-related outcomes, especially to job performance. For instance, Xanthopoulou et al. (2009) provided evidence for the positive impact of daily work engagement on daily financial returns. But the effects of work engagement are not limited to the work setting. The literature on work and family emphasizes that negative and positive experiences lived in one domain (i.e., work) may be transferred to another domain (i.e., home), which is known as a spillover effect (Edwards and Rothbard 2000). The study by Schaufeli et al. (2008) counts among the few that provides evidence that work engagement has a favorable impact on the individual in the form of good social functioning and better health. In a week-level study, Sonnentag et al. (2008) found that a person’s general level of work engagement was positively related to positive affect and negatively related to negative affect at the end of the working week. Moreover, the benefits of daily psychological detachment on positive affect were higher among those individuals with high levels of trait work engagement. Therefore, it seems that being focused on one’s work may prevent from concentrating on negative events. Instead, it creates a state of positive affect. Taken together, these studies suggest that being engaged at work can improve the quality of life outside the work domain. According to Greenhaus and Powell (2006), the experiences lived in one domain may improve the quality of life in the other domain.

In the present study, we propose that on days when employees are more engaged at work, they will report higher levels of happiness in the evening. We focus on this outcome because it is a general indicator of subjective well-being. As Kashdan et al. (2008) pointed out, researchers on subjective well-being agree that happiness represents “a variety of subjective evaluations about the quality of one’s life, broadly defined” (p. 221). Although subjective well-being can be measured across time, Kashdan and colleagues propose capturing it over time spans such as days, weeks or months in order to avoid biased recollections which may be inconsistent with the moment-to-moment experiences. In the same vein, Kahneman (1999) considered that happiness could be better measured by observing people’s momentary experiences. On the basis of this literature, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 1

Employees’ daily work engagement will be positively related to daily happiness.

1.2 The Daily Crossover of Happiness

The SCM (Bakker and Demerouti 2013) postulates that work-related experiences first spill over to the home domain, and then cross over to significant others. The term crossover has been defined as “the reaction of individuals to the job stress experienced by those with whom they interact regularly” (Westman 2001, p. 717). In subsequent advancements of crossover theory, Bakker and colleagues have encouraged researchers to examine the SCM using positive indicators (e.g., Bakker et al. 2009). There is evidence for the crossover of negative experiences such as burnout (Westman and Etzion 1995), depression (Westman and Vinokur 1998), or work-family conflict (Hammer et al. 1997). These studies refer to direct effects, that is, the phenomenon of burnout, depression or work-family conflict are directly transmitted to the partner, and vice versa. Demerouti et al. (2005) have referred to this as “symmetric crossover effects between partners” (p. 270). Although some cross-sectional studies have also analyzed the crossover of life satisfaction (Demerouti et al. 2005), or flow at work (Bakker 2005), research about positive experiences is not so highly developed compared to those studies focused on the negative side. What is more, if we search for more innovative designs, with the exception of the crossover of daily work engagement among colleagues (Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009), and the crossover of well-being among couples (Sanz-Vergel et al. 2012), to our knowledge, studies have not examined the crossover of positive experiences on a daily basis.

In our first hypothesis, we proposed a spillover effect of work engagement in terms of happiness. Based on the SCM (Bakker and Demerouti 2013), we consider that employee’s happiness is not only experienced by the employee, but it may also be transmitted to the partner. Indeed, Fredrickson (2001) suggests that experiences of positive emotions prompt individuals to engage with their environments and to make more social contacts. The main underlying mechanism explaining the crossover of positive emotions, including happiness, is emotional contagion. Hatfield et al. (1994) refer to emotional contagion as people’s tendency to imitate the facial and body expression seen in others, and the ability to “catch” others’ emotional states, converging emotionally. We propose a crossover of happiness among couples under the assumption that emotional contagion is most likely among people with close relationships. In an experimental study, Kimura et al. (2008) demonstrated that the level of intimacy facilitates emotional contagion. Experiences of happiness crossed over especially among those who shared the highest degree of intimacy (e.g., friends vs. acquaintances). In the light of these results, one could argue that if employees feel happy when they are at home, they will tend to approach their partners and to share this positive state with them, a process denominated “work-family interpersonal capitalization” (Ilies et al. 2011). At the same time, given the tendency of people to “catch” other individuals’ emotions, employees can also benefit from their partner’s happiness. Thus, there is a bidirectional crossover of happiness, from one member to the other and vice versa. Based on these arguments, we hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2

Employees’ daily happiness will be positively related to their partner’s daily happiness.

Finally, we examine the indirect effects of daily work engagement on partner’s daily happiness. In that way, we complete the process suggested by the SCM Bakker and Demerouti 2013), which starts with a work experience that spills over to the home domain (intra-individual effect), and after that, crosses over to the partner (inter-individual effect). Bakker and Demerouti already suggested that employees who enjoy their work may feel self-efficacious after a day at work, and may go home in a positive mood. This state of work-family enrichment can have a positive impact on partner’s well-being. This means that work engagement may have benefits not only for the organization or the employee, but also, indirectly, for the partner’s happiness. Thus, our last hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3

Employees’ daily work engagement will have a positive effect on partner’s daily happiness through employees’ daily happiness (Mediation Hypothesis).

2 Method

2.1 Procedure and Sample

We collected data from employees working in different organizations in Spain. Participants were recruited trough the social networks of the researchers and their students. Participants had to first fill in a general questionnaire followed by a diary survey twice a day during five consecutive working days (Monday–Friday). Specifically, work engagement was assessed at the end of the workday, whereas happiness levels were reported before going to bed. To guarantee confidentiality, responses of partners were linked by means of anonymous codes provided by the participants. These codes included their year of birth and gender as well as answers to questions related to the birth year of participants or mother’s surname. All the information was sent back directly to the researchers.

Of the 150 survey packages distributed, 100 were returned (66 % response rate), which is considered a good response rate for diary research (Ohly et al. 2010). Fifty couples (N = 100 participants and N = 500 occasions) participated in the study. The prerequisite for participation was that both members of the couple had a job and were living together. Participants worked in a broad range of professional backgrounds, including financial institutions and business services, farming, construction, trade, industry, health and welfare, education and media. The final study sample consisted of 50 men (50 %) and 50 women (50 %). The average age of the participants was 37.05 years (SD = 9.58) and their mean organizational tenure was 15.65 years (SD = 9.31). On average, they worked 36.96 h per week (SD = 8.09). Almost half of the couples (51.5 %) had at least one child, while 35.8 % of the sample had a university degree or postgraduate studies. Most of them were salaried (93.5 %) and 37.5 % of the sample had a supervisory position.

2.2 Measures

Daily Work Engagement was measured with the daily version (Breevaart et al. 2012) of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al. 2006). We focused on the two core elements of work engagement, namely vigor and dedication (González-Romá et al. 2006). The third dimension (absorption) has generated some conceptual problems, given that it may overlap with other concepts such as workaholism (Schaufeli et al. 2008). Given that we focus on positive aspects, we decided to analyze the core components and exclude absorption. The scale includes three items for vigor (e.g., “Today, I felt strong and vigorous at my job”), and three items for dedication (e.g., “Today, I was enthusiastic about my job”). Items were rated on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 = not true at all to 6 = totally true. High scores on this scale indicate high levels of work engagement. The mean of Cronbach’s alphas across the five occasions was .81 and .80 for vigor and dedication, respectively.

Happiness: Our measure of daily happiness was based on Kunin (1955). It was measured using a single item with faces used as options. The scale consists of five faces, ranging from “very unhappy” to “very happy”.

Other variables: As additional, control variables, we measured gender, age, educational level, marital status, number of children, job status, organizational tenure, and number of work hours actually worked per week.

2.3 Data Analysis

Our data set is composed of three levels. Specifically, repeated measurements at the day level consisted the first one (within-person), individual persons the second level (between person), and the dyad the third level (between-dyad). To test the hypotheses, we conducted multilevel analyses with the MLwiN program (Rasbash et al. 2000) with three levels: day (Level 1; N = 500 observations), person (Level 2; N = 100 participants), and dyad (Level 3; N = 50 dyads). We centered predictor variables at the person level around the grand mean, and predictor variables at the day level around the respective person mean.

We analyzed our data following the actor–partner interdependence model (APIM; Kenny et al. 2008). This approach has been used in previous studies with a similar research design (e.g., Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009; Sanz-Vergel et al. 2012), considering the dyad as the highest unit of analysis, with individuals nested within the dyad. This model enables examining how an individual’s predictor variable simultaneously and independently relates to his or her own criterion variable (actor effect) and to his or her partner’s criterion variable (partner effect). In APIM models, the partner effect allows to test the mutual (i.e., reciprocal) influence between the members of the dyad (Kenny et al. 2008). In the current study, the crossover of happiness from the actor to the partner is tested simultaneously with the crossover from the partner to the actor.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

First, we calculated means, standard deviations, and correlations among all the variables of the study. For calculating the correlations we followed the approach of previous studies, where the average across all the days was included (e.g., Bakker and Xanthopoulou 2009; ten Brummelhuis and Bakker 2012). As can be seen in Table 1, the pattern of correlations was in the expected direction. Additionally, some demographic variables were related to the study variables, and we decided to control its effect in further analyses. Specifically, educational level was related to both actor’s (r = .17, p < .01) and partner’s daily happiness (r = .16, p < .01), whereas job status was significantly related to partner’s daily happiness (r = .10, p < .05). To provide statistical evidence for the use of a three-level (dyads, persons, days) model, we calculated whether our variables exhibited sufficient between and within persons variability. For each day-level variable, we calculated the intraclass correlations with the intercept-only model. Results indicated that the three-level models explained a significant amount of the happiness variance. Specifically, results showed that 38.9 % of the variance could be attributed to within-person variations, 25.6 % of the variance was attributable to between-person variations, and 35.5 % of the variance was attributable to between-dyad variations. These results clearly support the use of multilevel modeling with the three levels of analysis, because the variance attributed to the dyad was in all cases significant.

3.2 Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1 stated that individuals’ daily work engagement would be positively related to their own daily happiness. It’s important to underline that APIM models include information of the two members of the dyad simultaneously. To refer to how a person’s independent variable relates to his/her own dependent variable, we will refer to how an actor’s independent variable relates to an actor’s dependent variable. To test the first hypothesis, we compared three nested models. In the Null Model, we included the intercept as the only predictor. In Model 1, we included person-level control variables (demographic information). In Model 2, we entered Vigor and Dedication of both the actor and the partner. Finally, in Model 3, we entered partner’s happiness. Model 3 showed a better fit to the data than Model 2 (difference of −2 × log = 5.48, df = 1, p < .05), Model 1 (difference of −2 × log = 44.01, df = 5, p < .001), and the Null Model (difference of −2 × log = 109.86, df = 7, p < .001). Table 2 presents unstandardized estimates, standard errors, and t-values for all predictors. The results support Hypothesis 1, since actor’s daily happiness was positively related by actor’s daily vigor (t = 3.02, p < .01) and dedication (t = 2.17, p < .05).

Hypothesis 2 suggested that there would be bidirectional crossover of daily happiness between both members. Results showed that actor’s daily happiness was positively related to partner’s daily happiness (t = 2.53, p < .01). This finding supports Hypothesis 2.

Finally, Hypothesis 3 suggested that employees’ daily work engagement would have an effect on partner’s daily happiness through employees’ daily happiness The three conditions that should be met in order to support this mediation hypothesis are (a) actor’s daily work engagement (vigor and dedication) should be positively related to actor’s daily happiness; (b) actor’s daily happiness should be positively related to partner’s daily happiness, and (c) after the inclusion of the mediator (actor’s daily happiness), the previously significant relationship between daily actor’s work engagement (vigor and dedication) and daily partner’s happiness turns into non-significance (full mediation) or becomes significantly weaker (partial mediation; Mathieu and Taylor 2006). The test of Hypothesis 1 and 2 already supported the first two requirements. Regarding the third condition, results showed that neither actor’s daily vigor (t = 0.90, p > .05) nor actor’s daily dedication (t = 0.45, p > .05) were significantly related to partner’s happiness. Thus the third condition was not supported. Mathieu and Taylor (2006) have suggested that in cases where mediation hypotheses are rejected, alternative hypothesis of indirect effects should be examined. Indirect effects are a special form of intervening effects whereby the predictor and the dependent variable are not related directly, but they are indirectly related through significant relationships with a linking mechanism. We tested this indirect effect with the Sobel (1982) test. Results showed that showed both actor’s daily vigor (z = 2.13, p < .05) and dedication (z = 2.08, p < .05) indirectly, positively relates to partner’s daily happiness via actor’s daily happiness. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is partially supported.

4 Discussion

Drawing from the SCM (Bakker and Demerouti 2013), we predicted that work engagement would spill over to the home domain in the form of happiness, and in turn, happiness would be transmitted to the partner. We used a daily diary design, as recommended by scholars to implement a process perspective in work and organizational psychology (Ohly et al. 2010). Furthermore, our study responds to the call for research on daily work engagement (Bakker et al. 2008), as well as on happiness (Kahneman 1999).

Taken together, our findings show that the positive effects of work engagement go beyond the work setting and beyond the employee. Moreover, we add to the few studies showing that work engagement may vary from day to day. First, we found that daily work engagement is positively related to happiness. As Bakker (2009) argued, engaged employees often experience positive emotions, including happiness, joy, and enthusiasm. We provide evidence for this contention on a daily basis. Moreover, our results are in line with recent research linking work engagement with work-family issues. For instance, using an experience-sampling approach, Culbertson et al. (2012) found that daily work engagement was related with positive mood at home, which in turn, led to higher levels of daily work-family facilitation. However, work engagement may also have a negative impact on private life. In a longitudinal study, Halbesleben et al. (2009) found that work engagement at Time 1 led to higher levels of work-family conflict 1 year later, and that this relationship was mediated by organizational citizenship behaviors. Future research is needed to better understand how work engagement relates to experiences lived outside the work domain. Second, we analyzed whether daily happiness crosses over to employees’ partner. Results are in line with cross-sectional studies showing the crossover of positive experiences (Demerouti et al. 2005). However, we provide evidence of the crossover of a positive experience, on a daily basis. The underlying mechanism for this crossover may be an emotional contagion process (Hatfield et al. 1994), so that each member of the couple is able to “catch” the other’s emotional state and converge emotionally. Moreover, the crossover is bidirectional, which means that each member of the couple is not only the receiver but also the sender. The question is why people with high levels of daily happiness transmit this emotional state. As Fredrickson (2001) suggested, people experiencing positive emotions tend to approach people. In the light of our results, we could argue that people with high levels of daily happiness tend to share this positive state with the partner, which may result in emotional contagion. As Fowler and Christakis (2009) pointed out, apart from contextual factors, people are happy because of the happiness of others with whom they are connected.

Third, we proposed that employees’ daily work engagement would have an effect on partner’s daily happiness through employees’ daily happiness. Results support an indirect effect, showing that daily work engagement has positive effects not only for the employee but also for the partner in an indirect way. This result is in line with Bakker and Demerouti (2009), who demonstrated that work engagement had an impact on employee’s performance and also indirectly on partner’s performance. We go one step further by demonstrating that work engagement has an impact not only on work-related outcomes such as performance, but also on emotional states. It is worth mentioning that work engagement was not directly related to partner’s well-being. Indeed, one could argue that work experiences of the employee do not necessarily have to affect the partner in a direct way. Note also that Bakker and Demerouti did not found a direct effect of work engagement on partner’s performance. It was indirectly transmitted through the crossover of engagement (women’s work engagement indirectly influenced men’s performance, through men’s work engagement). However, it would be interesting to analyze how work and non-work experiences are transmitted between those couples working together. It has been found that being in a work-linked relationship has benefits such as spouse instrumental support, but also disadvantages such as the increase of strain-based work-family conflict (Halbesleben et al. 2012).

4.1 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, one possible limitation of this study is related to the design strategy. Although the diary designs offer several benefits, such as the reduction of response bias or the possibility to take into account daily fluctuations of the variables under study, they do not allow conclusions about long terms effects. According to Fredrickson and Joiner (2002), positive emotions create an upward spiral toward improved emotional well-being. Thus, future week-level and longitudinal studies could examine whether the crossover of happiness has positive effects in the long term.

Second, happiness was measured with a single item, raising the concern about the reliability of the measure. Although it has been pointed out that measures of multiple items reduces measurement error and tends to increase reliability, previous research has shown that single item measures for satisfaction and well-being constructs are valid and reliable. For instance, Diener (1984) has found convergent validity between single-item and multi-item measures of global satisfaction, suggesting that single-item measures are adequate if one desires a “brief measure of global well-being” (p. 544). Similarly, Scarpello and Campbell (1983) have underlined that single-item satisfaction measures may be more inclusive measures of overall satisfaction than summations of many-facet responses. In the field of happiness, Abdel-Khalek (2006) showed that a single item measure for happiness has good temporal stability and concurrent, convergent, and divergent validity. Furthermore, in diary designs the use of short measures as well as single items has been strongly recommended in order to minimize the impact of data nonresponses (Ohly et al. 2010, p. 86). In this sense, a single-item measure also reduces the fatigue, frustration, and boredom associated with answering the same questions several times a day, for several days. Nevertheless, future studies could use specific measures to analyze particular aspects of happiness on a daily basis.

A third possible limitation is that although we had three levels (days, members, and couples) of analysis in our study, we did not include specific variables at the couple’s level. Since the variance explained by each level supports the use of these three levels, more research is needed to explore variables at the couple level (e.g., the frequency of positive interactions during the evening, common experiences like the birthday of a family member) that might have an influence on happiness.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that APIM is designed to measure interdependence in data from dyad members, which means that one person’s emotion, cognition, or behaviour may have an impact on the emotion, cognition, or behaviour of the partner (Kenny and Cook 1999). The actor and partner effects of the APIM may simply indicate a significant relation, not necessarily a causal one (Cook and Kenny 2005). This is the approach that we followed in the present study, which assumes a bidirectional relationship (crossover). Thus, we cannot conclude in causal terms.

4.2 Practical Implications

According to previous research (e.g., Bakker 2009) the main antecedents of work engagement are job resources. The main intervention at the organizational level could be increasing autonomy, supervisor support or provided feedback, so that employees may feel engaged. It would be also interesting to provide employees with training programs to increase emotional competences. For instance, it has been shown that sharing positive events helps to increase work-family facilitation (Culbertson et al. 2012). As suggested by Bakker (2005), organizations could use the advancements in crossover research to provide resources to their employees. These resources may enhance positive experiences at work and at home, creating positive spirals in both domains. Kashdan et al. (2008) stated that human beings are happiest when they are engaged in meaningful pursuits (p. 230). Being engaged at work seems to be one possible road to improve one’s daily happiness, and an indirect way to one’s partner’s happiness.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006). Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Social Behavior and Personality, 34, 139–150.

Bakker, A. B. (2005). Flow among music teachers and their students: The crossover of peak experiences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 26–44.

Bakker, A. B. (2009). Building engagement in the workplace. In R. J. Burke & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The peak performing organization (pp. 50–72). Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). The crossover of work engagement between working couples: A closer look at the role of empathy. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 220–236.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The Spillover–Crossover model. In J. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research. Hove: Psychology Press (in press).

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Burke, R. (2009a). Workaholism and relationship quality: A Spillover–Crossover perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14, 23–33.

Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22, 187–200.

Bakker, A. B., Westman, M., & Van Emmerik, I. J. H. (2009b). Advancements in crossover theory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24, 206–219.

Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2009). The crossover of daily work engagement: Test of an actor-partner interdependence model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1562–1571.

Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Hetland, J. (2012). The measurement of state work engagement: A multilevel factor analytic study. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28, 305–312.

Cook, W., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101–109.

Culbertson, S. S., Mills, M. J., & Fullagar, C. J. (2012). Work engagement and work-family facilitation: Making homes happier through positive affective spillover. Human Relations, 65, 1155–1177.

Demerouti, E. (2012). The spillover and crossover of resources among partners: The role of work-self and family-self facilitation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17, 184–195.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Spillover and crossover of exhaustion and life satisfaction among dual-earner parents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67, 266–289.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25, 178–200.

Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2009). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. British Medical Journal, 7685, 338–347.

Fredrickson, B. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13, 172–175.

González-Romá, V., Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Lloret, S. (2006). Burnout and work engagement: Independent factors or opposite poles? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 165–174.

Greenhaus, J., & Powell, G. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Harvey, J., & Bolino, M. C. (2009). Too engaged? A conservation of resources view of the relationship between work engagement and work interference with family. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1452–1465.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Wheeler, A. R., & Rossi, A. M. (2012). The costs and benefits of working with one’s spouse: A two-sample examination of spousal support, work-family conflict, and emotional exhaustion in work-linked relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 597–615.

Hammer, L. B., Allen, E., & Grigsby, T. D. (1997). Work-family conflict in dual-earner couples: Within individual and crossover effects of work and family. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 185–203.

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rapson, R. L. (1994). Emotional contagion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ilies, R., Keeney, J., & Scott, B. A. (2011). Work-family interpersonal capitalization: Sharing positive work events at home. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114, 115–126.

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: the costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 219–233.

Kenny, D. A., & Cook, W. (1999). Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships, 6, 433–448.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2008). Dyadic data analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Kimura, M., Daibo, I., & Yogo, M. (2008). The study of emotional contagion from the perspective of interpersonal relationships. Social Behavior and Personality, 36, 27–42.

Kunin, T. (1955). The construction of a new type of attitude measure. Personnel Psychology, 9, 65–78.

Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 1, 3–30.

Mathieu, J. E., & Taylor, S. R. (2006). Clarifying conditions and decision points for meditational type inferences in organizational behaviour. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 1031–1056.

Ohly, S., Sonnentag, S., Niessen, C., & Zapf, D. (2010). Diary studies in organizational research: An introduction and some practical recommendations. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9, 79–93.

Rasbash, J., Browne, W., Healy, M., Cameron, B., & Charlton, C. (2000). MLwiN (Version 1.10.006): Interactive software for multilevel analysis. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Institute of Education, University of London.

Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2012). The daily spillover and crossover of emotional labor: Faking emotions at work and at home. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81, 209–217.

Scarpello, V., & Campbell, J. P. (1983). Job satisfaction and the fit between individual and organizational rewards. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 56, 315–328.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701–716.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of burnout and engagement: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92.

Schaufeli, W. B., Taris, T. W., & Van Rhenen, W. (2008). Workaholism, burnout, and work engagement: Three of a kind or three different kinds of employee well-being? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 173–203.

Shimazu, A., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2009). How job demands influence partners’ well-being: A test of the Spillover–Crossover model in Japan. Journal of Occupational Health, 51, 239–248.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhardt (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). Washington, DC: American Sociological Association.

Sonnentag, S., Dormann, C., & Demerouti, E. (2010). Not all days are created equal: The concept of state work engagement. In M. P. Leiter & A. B. Bakker (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 25–38). New York: Psychology Press.

Sonnentag, S., Mojza, E. J., Binnewies, C., & Scholl, A. (2008). Being engaged at work and detached at home: A week-level study on work engagement, psychological detachment, and affect. Work and Stress, 22, 257–276.

ten Brummelhuis, L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). Staying engaged during the week: The effect of off-job activities on next day work engagement. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17, 445–455.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Xanthopoulou, D. (2011). Do transformational leaders enhance their followers’ daily work engagement? The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 121–131.

Westman, M. (2001). Stress and strain crossover. Human Relations, 54, 557–591.

Westman, M., & Etzion, D. (1995). Crossover of stress, strain and resources from one spouse to another. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 169–181.

Westman, M., & Vinokur, A. (1998). Unraveling the relationship of distress levels within couples: Common stressors, emphatic reactions, or crossover via social interactions? Human Relations, 51, 137–156.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 183–200.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., Sanz-Vergel, A.I., Demerouti, E. et al. Engaged at Work and Happy at Home: A Spillover–Crossover Model. J Happiness Stud 15, 271–283 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9421-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9421-3