Abstract

Despite strong evidence in favor of physical activity (PA), adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are not meeting established PA guidelines to engage in at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA per week. Barriers to daily PA engagement include limited access to health services, transportation, and reduced self-determined motivation. Telehealth provides a potential alternative to deliver PA programming in a more accessible platform for adults with ASD. This pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) assessed the preliminary efficacy of a 10-week PA intervention program called Physical Activity Connections via Telehealth (PACT) that utilized telehealth and remote technology, including Fitbit wearable device use, peer-guidance, and individualized home exercise program among adults with ASD. Primary health outcomes, collected at baseline before randomization and post-intervention, included self-determined motivation assessment via Behavioral Exercise Regulation Scale (BREQ-2), self-report PA via Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire (GSLT-PAQ), steps per day PA via Fitbit device, body mass index (BMI), and waist-to-height ratio (WtHR). A total of 18 adults, 11 males, with a mean age of 26.4 years, with a primary diagnosis of ASD participated in the study. Although there were no changes in BMI or WtHR at post-intervention, participants receiving PACT, significantly increased both their self-report PA scores (GSLT-PAQ) from 26 to 68, (p = 0.002), and steps per day from 5,828 to 7,443, (p = 0.015) with a moderate effect size (d = 0.72). The results of this pilot study support peer supported telehealth-based PA intervention for adults with ASD to increase PA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite the strong evidence in support of physical activity (PA) guidelines recommend all adults to engage in at least 150 min of moderate to vigorous PA per week (Piercy et al., 2018; US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2018), adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are less likely to meet these guidelines and therefore at higher risk for non-communicable chronic diseases than their peers without autism (Hillier et al., 2020; Weir et al., 2021). PA is defined as any body movement generated by the contraction of skeletal muscles that raises energy expenditure above resting metabolic rate, is characterized by its modality, frequency, intensity, duration, and context of practice as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure (Caspersen et al., 1985). Propensity towards physical inactivity, or non-achievement of PA guidelines (Thivel et al., 2018) among adults with ASD may stem from autism’s lifelong effects on social communication, social behavior, motor skills, and executive function (American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders:DSM-5, 2013; Bhat, 2021; Croen et al., 2015; Narzisi et al., 2013). Additionally, parents and caregivers report that challenges to PA for their adult children with ASD stem from hypersensitivity, limited motor skills, and family's socioeconomic status (Nichols et al., 2018), while low self-determined motivation towards PA (Hamm & Yun, 2018; Healy et al., 2021) inaccessibility of community programs or spaces, and lack of acceptance (Buchanan et al., 2017) create further barriers to PA engagement. Poor PA engagement increases vulnerability towards obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes, which are more prevalent in adults with ASD compared to adults without an ASD diagnosis (Croen et al., 2015). Physical inactivity is among the top four modifiable behavioral risk factors for poor health outcomes and global mortality (WHO, 2017). Race, ethnicity, low social economic status, and other demographic factors further contribute to these negative health outcomes for adults with ASD who are already at greater risk for adverse health outcomes (Bishop-Fitzpatrick & Kind, 2017). A deepening concern and gap in autism research is the underrepresentation of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Asian participants as they account for only 7.7%, 9.4%, and 6.4%, of study participants respectively, while White non-Hispanic participants make up 65% of participants (Steinbrenner et al., 2022).

Furthermore, impairments in motor function, coordination, balance, visual-motor coordination, and gait are commonly identified among children with ASD, and is considered a cardinal feature of ASD (Fournier et al., 2010), however, only a small proportion will receive movement-based therapeutic interventions (Bhat, 2021). A study by Cho et al. examining movement patterns of adults with ASD without intellectual impairments, revealed greater gait deviations and abnormal gait patterns, such as greater body sway during tandem and single leg stance, reduced walking speed and cadence, irregular timing during jumping jacks and impaired manual dexterity during finger tapping tasks compared to healthy non-autistic cohort (Cho et al., 2022). Consequently, unaddressed developmental movement-related impairments may continue to have long-term consequences on daily physical function throughout adulthood (Cousins & Smyth, 2003) and a propensity towards insufficient PA and sedentary behavior (Bhat, 2021; Fournier et al., 2010; Lord et al., 2022).

Peer Engagement and Self-Determined Motivation

Although reported barriers to PA engagement have long-term health consequences for adults with ASD, theoretical frameworks and facilitators have been identified to assist in mitigating physical inactivity. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is a theoretical framework which delineates the motivational process to foster PA behavior and underscores three basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000). SDT is based on the belief that motivation lies on a continuum that ranges from amotivation, having no motivation, to intrinsic motivation, where one engages in a behavior for the inherent joy of the activity (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Psychological components of SDT, (competence and autonomy) is predictive of PA motivation among adults with ASD (Hamm & Yun, 2018). SDT was previously utilized for a 10-week peer mentored PA program for adults with ASD and was found to be beneficial to PA outcomes. The program incorporated preferred activities and self-directed instruction (autonomy), skills attenuation through expert instruction (competence), and engagement socially with peers (relatedness) (Todd et al., 2019).Other approaches that use classic behavioral change strategies such as problem-solving and skills building related to PA also assist in identifying and overcoming challenges and barriers to PA (Bailey, 2019). Moreover, mastery of a goal helps facilitate individuals to persist in their behavior change efforts when feeling challenged or discouraged (Bailey, 2019). Mastering goals encourages problem solving and active engagement (Heyman & Dweck, 1992). Interventionists may be able to lead more successful and inclusive PA programs by structuring interventions targeting autonomy, competence, relatedness, and SMART goal setting (Bailey, 2019; Edmunds et al., 2008). There is also evidence that intrapersonal and interpersonal, community, and institutional factors facilitate PA engagement among children and young adolescents with ASD (Obrusnikova & Cavalier, 2011).

Developmentally, young adults are more autonomous than adolescents and look more to peers and significant others, rather than parents, for support to be physically active. A small pilot study with college students with ASD revealed improved cardiorespiratory fitness, flexibility, and upper body muscular endurance as a result of participation in peer led in-person PA intervention (Todd et al., 2019). Authors of this study also reported that students felt that: they gained motor competence, improved their health, and felt a sense of belonging (Todd et al., 2019). Although further studies are necessary to understand the specific needs in adults with ASD, pediatric studies and emerging pilot interventions with adults with ASD lend support to the use of a multipronged approach when developing a PA intervention for adults with ASD. As a potential avenue for prevention, physical literacy (PL) development has been emphasized through quality sport and recreation programs, and physical education curriculum delivery for all children, including those diagnosed with ASD.

Walking and Wearable Activity Trackers

PA engagement fosters improved locomotor and skill-related fitness (LaLonde et al., 2014; Lang et al., 2010), social-emotional function, and quality of life (Bremer et al., 2016; Dickinson & Place, 2014; Tomaszewski et al., 2022). PA activity tracking with consumer-based wearables such as Fitbit has gained popularity and acceptance in both the non-autism and autism research community for its ability to record objective measures of PA via steps per day and its relatively high correlation with research grade accelerometers (LaLonde et al., 2014; Savage et al., 2022; Toth et al., 2018). Steps per day reflects an objective metric of the overall amount of walking undertaken during one's everyday life and may serve as a marker of health and disability status in patients with neurological disorders (Pearson et al., 2004; Sandroff et al., 2014). A recent meta-analysis identified that increasing daily steps to at least 8,000 – 10,000 progressively decreased risk of all-cause mortality for adults under 60 years of age (Paluch et al., 2021). Previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis also support the utility and effectiveness of behavioral interventions to increase the number of steps taken by for adults without autism and who are sedentary (Sullivan & Lachman, 2016) and for adults with obesity (Samdal et al., 2017).

Although intervention research utilizing consumer-based wearables to increase steps per day specifically for adults with ASD is still emerging, the concomitant use of behavioral strategies such as prompting, modeling, positive reinforcement/praise, structured teaching, and goal setting reveal promising feasibility, however with mixed health outcomes (LaLonde et al., 2014; Ptomey et al., 2021; Savage et al., 2018, 2022). For example, among a small sample of 5 adults with ASD, adopting goal setting and praise along with Fitbit activity tracker use, PA increased to over 10,000 steps per day (LaLonde et al., 2014). Most recently, Step It Up program (consisting of weekly exercise, coaching weekly goal setting meetings, self-management checklist, and pictorial task analyses with the Fitbit activity tracker) was shown to improve steps counts and weight reduction in adults with autism and intellectual disability (Savage et al., 2022). As individuals with autism move through adolescence and into adulthood, walking with a wearable activity tracker may be more practical and realistic to initiate, achieve, and sustain PA goals.

Covid-19 and Telehealth

While the benefits and emerging health outcomes research on the effects of PA for adults with ASD is encouraging, the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, was particularly disruptive for the autism community (Bal et al., 2021). Health and safety measures that were put in place to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 also meant that adults with ASD experienced changes in their familiar environments and routine. In addition to a greater susceptibility to infection severity due to potential co-morbidities, or difficulty with precautionary behaviors (i.e., washing hands, mask use) as needed, most adults with ASD reported that Covid-19 pandemic negatively impacted their mental health (Chung, 2020). Social isolation was especially heighted as most public parks where community-based programs are likely to take place were closed, and adults with ASD reported difficulty talking openly with a mental health therapist while at home (Chung, 2020). Specifically, in our local community, a university sponsored community-based PA program led by physical therapy faculty for adults with ASD was suspended for health precautions. In general, adults with ASD experienced reduced access to health services and therapies, and many reported experiencing declining mental health and greater depression and anxiety as a result of COVID-19 disruptions (Chung, 2020).

Telehealth further emerged in the forefront throughout the pandemic and beyond, increasing in popularity as it leverages electronic and telecommunication technologies to support long-distance clinical services, patient and professional health-related education (Seron et al., 2021; HealthIT, 2017). Telehealth is beneficial in reducing patient costs related to time and travel for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Clark et al., 2019; Lindgren et al., 2016). In an interventional study that included adolescents with intellectual disabilities and autism diagnosis, teleconference use (30-min classes three times per week for 12 weeks) to increase PA was found to be feasible with good participant compliance (Ptomey et al., 2021). Feasibility and effectiveness of telehealth delivered PA intervention has been studied in children with ASD (J. M. Garcia et al., 2021a, 2021b; Yarımkaya et al., 2022) and among adults with other developmental disabilities such as Rett Syndrome (Downs et al., 2023), however, results are mixed. Moreover, effectiveness of telehealth PA has not been studied with adults with ASD, who have a unique set of strengths, needs and challenges related to PA engagement and the use of technology. For example, among children and adolescents with ASD, and with higher verbal abilities, explicit instruction (verbal and/or visual), modeling, repeated practice, and feed-back/reinforcement may easily be incorporated with telehealth technology (Srinivasan et al., 2014). When needed, clinicians may also simplify visual instruction (e.g., slowing the speed of demonstrations) and provide ongoing visual cues to improve motor imitation for all participants (Baranek et al., 2014).

Physical Activity Connections via Telehealth (PACT)

Physical Activity Connections via Telehealth (PACT), a telehealth delivered PA program, was developed and piloted following the initial Covid-19 quarantine lockdown to provide a source of community engagement aiming to improve PA in adults with ASD (Tovin & Nunez-Gaunaurd, 2024). The feasibility and acceptability of the PACT intervention among young adults with ASD was previously examined (Tovin & Nunez-Gaunaurd, 2024). To our knowledge, there are no studies examining the effectiveness of a peer-supported telehealth PA intervention combined with Fitbit activity trackers on self-determined motivation, PA levels, and adiposity, of adults with ASD. Therefore, primary objective of this study was to conduct a 10-week pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effects of PACT on self-determined motivation, PA, and adiposity among adults with ASD. We sought to answer the following research question: Compared with having access to a Fitbit and Fitbit resources (control), does the PACT program result in increased self-determined motivation, engagement in PA, and improved adiposity, for adults with autism? We predicted that participants in the PACT program intervention would take more average steps per day, have a higher perceived self-determined motivation, and decrease body mass index (BMI) compared with participants in the control group, controlling for baseline. It is anticipated that the results of the study will contribute to the stakeholders (adults with ASD, parents, and caregivers of adults with ASD) on how to increase the PA levels through telehealth online platform.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a pilot RCT to promote PA among adults with autism with a focus on increasing steps per day. This pilot study utilized a randomized wait-list controlled design. The study had a two-arm, unblinded, parallel group design, comparing the PACT intervention: Fitbit, weekly telehealth peer group, home exercise instruction, and goal setting for step counts vs Fitbit-only as the wait-list control. Adults were randomized to the wait list control group also received an informational handout on PA and daily step count recommendations provided to the public (e.g., 10,000 step pers day). All participants underwent data collection at baseline and at 10-weeks post-intervention. Given that adults with ASD are at high-risk for physical inactivity and obesity, the investigative team found it most appropriate to use a wait-list control group so that all participants have the opportunity to receive the intervention. This wait-list control design allowed us to examine the added effect of PACT and Fitbit use as compared to just the Fitbit use alone. Upon completion of the 10-week intervention period, adults in the wait-list control group were invited to participate in the full PACT intervention.

This study was conducted in collaboration and IRB approval from two universities. Procedures for this study included, a pre-phone call screening, online visit to determined eligibility, pre-assessment surveys, baseline assessments randomization to either intervention or wait-list control, 10-week PACT or Wait-List Control, post-intervention/Wait-list assessments, group cross-over, 10-week intervention or Follow-up. At the conclusion of baseline testing, participants were randomized to either the 10-week PACT intervention or wait-list control for 10-weeks. Every candidate’s contact was logged and screened by the primary investigator (PI) to explain the study commitment and determine eligibility based upon pre-determined inclusion criteria and subsequently enrolled with the IRB approved consent form. Health outcomes and PA assessments were completed on all consenting participants at baseline, pre-intervention (for wait-list control group at time of cross-over) and at post intervention.

Participants

Participants were recruited via email blast to registered adult members of a Center for Autism and Related Disabilities (CARD) serving three counties in Southeast Florida. Interested individuals contacted a study principal investigator directly via email or phone and were screened for eligibility. To ensure participants would be able to access and utilize telehealth and supporting technologies, a vigorous screening protocol was developed and implemented. Study inclusion criteria consisted of adults between 18 and 32 years of age with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (confirmed with local autism registry), legal adult status (i.e., able to consent, not currently under guardianship), resident of tri-county area, own or have access to a smart phone, tablet/computer, and access to available internet/Wi-Fi, and ability to perform technology-related tasks, and no report of health issues or medical history that would limit PA or exercise. Individuals were excluded if they 1) did not meet the eligibility criteria above; 2) had experience (past or current) using a wearable activity tracker; 3) had experience with telehealth/remote-guided exercise; or 4) independently engaged in PA on a regular basis (i.e., without regular support or assistance) for an extended period (i.e., 3 months or longer). Prior participation in a community-based exercise program did not preclude participation. Adults with ASD often experience poor outcomes from PA programs because these programs do not adequately address their unique needs (Blagrave et al., 2021). PACT aimed to minimize barriers faced in other programs, improve access, and address population needs by incorporating evidence-based strategies. Although there are no gold standards for assessing consent, the study protocol is a modified version of a screening tool used by CARD staff to broadly determine an individual’s social communication and cognitive skills for placement into training and support groups (Tovin & Nunez-Gaunaurd, 2024). All study-related documents were available in English and Spanish with bilingual/bicultural research staff administering consent, collecting data, and answering questions. Figure 1 illustrates the study design and participant recruitment flow.

Physical Activity Connections via Telehealth (PACT) Intervention

PACT spanned 12-weeks in total, starting with a 1-week pre-program period for instruction, technology set-up, and baseline data collection. The intervention period lasted 10 weeks, followed by a 1-week post-program period for survey data collection and final home program instructions. Baseline data, including PA, exercise preferences, and PA resources (e.g., home and community space and equipment, family membership to a gym) were used to develop customized home exercise programs.

The PACT program is grounded in the Self Determination Theory to optimize PA engagement (Ntoumanis et al., 2021) by targeting the three basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. PACT weekly objectives were: (a) to facilitate knowledge and engagement in different PA practices for which participants expressed initial interest or enjoyment; (b) to support participants’ autonomy with management of PA practice; and (c) to teach self-management for the Fitbit application, and maintenance, adherence, and tracking for goal achievement. Competence for PA engagement was supported through individual and small group exercise instructions, return demonstrations of exercises with corrections as needed, progress toward meeting weekly SMART goals, and reflection on weekly step activity performance and exercise compliance. Education on PA benefits, recommendations and exercise frequency, intensity and timing goals were based on the Physical Activity Guidelines 2nd edition (US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2018). Fitness Support Pod members met weekly for 1-h via telehealth videoconferencing to engage in a semi-structured discussion aimed to celebrate successes and trouble-shoot challenges. Fitness Support Pods consisted of 3 PACT study participants, two peer leaders (Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) students) and an autism research faculty. Fitness Support Pod members also established team or group step goals for each coming week. The social context of the Fitness Support Pod reinforced SDT’s relatedness. Pod members were connected throughout the 10-weeks using the mobile Fitbit app (Fitbit, Inc.) by forming a personalized Fitbit community. A detailed description of all PACT intervention strategies is available in Table 1.

PACT introduced and reinforced individualized PA practices as recommended by the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, (US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2018), including aerobic and musculoskeletal strengthening exercises during their weekly telehealth sessions. Select strengthening exercises (trunk, upper/lower extremities exercises) were introduced during the first two weeks based on participants' priorities, identified limitations, accessible resources, and activity preferences. The exercises were progressed through weeks 3–10 by applying the FITT (Frequency, Intensity, Time, and Type) principal (Barisic et al., 2011). In addition, POD leaders addressed movement related questions and requests for feedback when appropriate. A pre-determined resistance training regimen (video and written instructions/), resources (e.g., resistance bands, exercise, or yoga mat), and aerobic regimen (e.g., outdoor walking, biking, skating), was introduced and reinforced with real time demonstrations and feedback, and guidance for correct performance. For example, if at baseline assessment, a participant reported an interest in improving their abdominal strength, the Fitness Support Pod leader would choose from the exercises that corresponded with abdominal and trunk strengthening such as standing trunk rotation with resistance bands, plank hold with proper positioning and supine abdominal curls. Flexibility exercises were introduced and demonstrated for the trunk, upper and lower extremities. Participants were instructed on a 5-min self-stretching program while receiving guidance on motor movement performance by Pod leaders, as well as additional video and written resources to promote competence and adherence. Overall progression of exercises depended on participant’s goal achievement, adherence, and feedback to encourage engagement.

Weekly Telehealth Meetings

Peer-assistance via the assigned fitness support pod, was provided remotely throughout the 10-week program. To further target SDT’s competence, participants received PA-related education on individualized PA daily step goals, and exercises informed by their pre-intervention assessment data. Proper Fitbit use, wearable features and displays, individual physical steps per day and minutes of moderate-to-vigorous PA, and the need for consistent wearing was reinforced as needed. Peer leaders provided PA adaptations and modification to weekly goals accordingly over the 10-weeks to facilitate success and confidence. Live weekly telehealth sessions reinforced new learned activities, updated home exercise programs, and provided opportunities for questions and answers between participants in a virtual social context. For example, if a step count goal of 10,000 steps/day was not achieved in week-2, a potential mastery goal for week-3 will include learning a new exercise activity or safe and enjoyable walking routes that facilitates PA by increasing step counts. Participants were encouraged to discuss updated preferences for PA schedule (frequency and timing), different exercises to increase PA (intensity and types), and accessible resources (e.g., access to bike, pool, individual/family gym membership, etc.,) which allowed the research team to develop custom home exercise program tailored to their needs, interests, and enjoyment. See Table 1. For an overview of PACT’s weekly health literacy and engagement topics to reinforce: 1. step count goals; and 2. musculoskeletal strengthening and flexibility exercises during their telehealth sessions.

Health Outcome Measures

Self-Determined Motivation

Self-determination toward PA and exercise motivation was measured using the Behavioral Exercise Regulation Scale (Mullan et al., 1997) as it examines the motivations for PA and exercising in connection with Deci and Ryan’s Self-Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). BREQ’s psychometric properties, including reliability and factorial, convergent, discriminant and predictive validity were previously confirmed (Mullan et al., 1997). The BREQ-2 version used in the present study contains 19 items related to 5 dimensions of motivation (extrinsic, intrinsic, identified, introjected, and amotivation regulation) scored on a 5-point Likert-scale (from 0 to 4) (Markland & Tobin, 2004). The relative autonomy index (RAI) is a single score derived from the subscales that gives an index of the degree to which respondents feel self-determined. Higher RAI score corresponds to more self-determined forms of motivation. RAI scores range from − 24 (strongly not self-determined) to 20 (highly self-determined) (Markland & Tobin, 2004). The BREQ-2 is one of the most widely used instruments in exercise motivation studies has been validated with a sample of 201 exercisers resulting in reasonable scores for both factor structure and internal consistency (Markland & Tobin, 2004).

Physical Activity

Subjective PA was assessed utilizing the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. (GSLT-PAQ) (Amireault & Godin, 2015). Test–retest reliability (Godin & Shephard, 1997) and interrater reliability (Amireault & Godin, 2015) were previously demonstrated on the GSLT-PAQ. Validity was determined by comparing with oxygen consumption and forced expiratory volume (Godin & Shephard, 1997). Additionally, GSLT-PAQ total scores can provide PA classifications corresponding to the American College of Sports and Medicine PA guidelines where ≥ 24 units is classified as active (Meeting PA guidelines), 14 ≤ 23 units is classified as moderately active (not meeting PA guidelines) and ≤ 13 units as insufficiently active (Amireault & Godin, 2015).

Objective PA was assessed using the Fitbit Inspire (Fitbit® Inc., San Francisco, California, USA), as it was also utilized throughout the 10-weeks for both wait-list control and PACT intervention groups. Fitbits are commercially available 3-dimensional accelerometers and altimeter that records the total amount of steps per day, an (Gusmer et al., 2014). Overall daily walking is also an indicator of health and disability status in people with neurological disorders (Pearson et al., 2004; Sandroff et al., 2014). Fitbit wearables have also previously met reasonable validity and reliability standards (Diaz et al., 2015). Additionally, the Fitbit flex uploads real-time data wirelessly to a web-based database for longitudinal tracking and data storage (FITABASE) (Messiah et al., 2008). All study related equipment, including activity monitors and wearables were provided via USPS residential delivery and local non-contact drop-off and pick-up methods. In addition, written and one-to-one, 1-h synchronous live instructions on telehealth were given to all participants for proper and consistent use of wearables, wearable set-up, charging/syncing data, explanations of wearable features and displays were provided. The study PI monitored wearable compliance and PA data syncing via Fitabase. A total of at least 4 days of walking activity data (3 weekdays and 1 weekend day) with at least 6 waking hours were selected for analysis. PA activity tracking with consumer-based wearables have a relatively high correlation with research grade accelerometers (Toth et al., 2018).

Adiposity

Anthropometric assessments were collected and documented virtually via teehealth using standardized guided instructions provided by the research team for height and weight (Himes, 2009). Height was self-reported, and weight was self-reported after the participant stood on their home weight scale. Waist circumference was also standardized in standing position using a standardized tape measure mailed out to all participants (NHANES, 2011). Body mass index (BMI) and Waist to Height Ratio (WtHR) was then calculated (CDC, 2022). Cardiometabolic risks was defined as > = 0.5 for higher-risk and < 0.5 for normal-risk WtHR as (Gibson & Ashwell, 2020).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed and interpreted using descriptive statistics and reported as mean (SD) or n (%) where appropriate of participants’ baseline characteristics. Demographic data were stratified by PACT intervention versus Wait-list Control group (WLC). Student’s t-test and Chi-square statistics were calculated to compare age, sex, race, ethnicity, PA self-determined motivation (SDM), and PA, and anthropometrics. A two-group mixed repeated measures analysis of variance was used to compare the change in SDM, PA, and anthropometrics, between the intervention and wait-list control groups. Effect sizes were calculated for change in SDM, PA, and adiposity, separately for the intervention group and wait-list control groups using Cohen’s d (mean a – mean b /sd) (Sullivan & Feinn, 2012).

Results

Table 2 presents demographic, self-determined motivation, PA and anthropometric measures of PACT intervention and waitlist-control groups. A total of 18 adults (11 males and 7 females) were equally randomized into PACT (n = 9) or WLC (n = 9) groups. The mean age of the cohort was 26 years of age. There was 100% retention throughout PACT intervention phases. Attendance to weekly telehealth sessions ranged from 70 to 100%, with a mean of 93%. Wearable adherence ranged from 20 to 100%, with a mean of 82%. There were no outliers in the Fitbit steps/day data as assessed by inspection of a boxplot, and steps per day data were normally distributed, as assessed by Shapiro–Wilk's test (p > 0.05). There were no significant differences at baseline in or self-determination, self-report leisure PA, steps per day, BMI, or WtHR, between PACT and WLC groups. Demographic characteristics and health outcomes revealed high adiposity as indicated by a mean BMI mean of 28.7 kg/m2 and WtHR of 0.56, respectively, indicative of overweight and high abdominal adiposity. With a mean steps per day of 7,210, only 33% reached at least 8,000 steps per day (reducing all-cause mortality risk). Additionally, more than 50% of the total cohort reported to be insufficiently active as per self-report PA (GSLT-PAQ).

Table 3 presents the results from the mixed repeated measures ANOVA between subjects (factor = PACT) and the within-subjects (factor = time), with RAI, GSLT-PAQ, steps per day and adiposity, as the dependent variables. Although RAI increased from 7.9 to 10.5, the interaction between PACT and time on RAI was not statistically significant (F (1,16) = 0.878, p = 0.363 Ƞ2 = 0.052. However, a significant interaction was found between PACT and time on self-report PA, GSLT-PAQ (F (1,16) = 12.97, p = 0.002 Ƞ2 = 0.448). The improvement in self-report PA among the PACT participants was significant compared to WLC group (26 to 68 vs 36 to 45, p = 0.002. The PACT group had a very large effect size (d = 2.60) and the WLC group had a large effect size (d = 0.57) in terms of GSLT-PAQ scores. Steps per day significantly improved among the PACT participants (Fitbit = 5,828 to 7,443), compared to a decrease in step counts with the WLC participants (8,593 to 7,588), (F (1,16) = 7.43, p = 0.015, Ƞ2 = 0.317). The PACT group had a moderate effect size for steps per day (d = 0.72) while the wait-list control group (Fitbit only) had minimal effect size (d = -0.26).

In addition, ANCOVA was conducted to analyze the effects of PACT on PA between pre-test and post-test. Controlling for baseline scores, a difference in GSLT-PAQ between the two groups was significant in favor of the PACT group, (F = 10.23, p = 0.006), with an effect size value of Ƞ2 = 0.41, indicating a significant strong effect from the intervention. More importantly, the difference in objective PA based on steps/day was also significant in favor of the PACT group, (F = 4.88, p = 0.043), with an effect size value of Ƞ2 = 0.25, indicating a significant moderate effect of the intervention. There was no statistically significant interaction between PACT and time on either BMI (F(1,15) = 0.191, p = 0.668, partial η2 = 0.013); or WtHR, (F(1, 15) = 0.460, p = 0.460, partial η2 = 0.037).

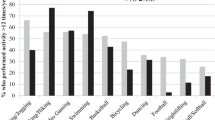

The nine participants in the intervention group and the nine participants in the wait-list group who crossed over and completed the intervention were part of a secondary analysis examining the effects of the PACT intervention in steps per day over time. Table 4 and Fig. 2 describes improvement in mean steps per day the intervention periods (pre-intervention, weeks 1–2, weeks 3–4, weeks 5–6, weeks 7–8, and 10-week post-test). A repeated measures ANOVA with a Greenhouse–Geisser correction determined that mean steps per day differed significantly between the six PACT intervention time periods (F (1.298, 11.663) = 26.938, P = 0.035). Table 5 describes the pairwise comparison of the change in steps per day across the 5 intervention time periods. Significant mean steps per day improvement is observed during the first four weeks, followed by non-significant decline in steps per day by week six. However, a significant increase in steps per day was observed between weeks 6–8 to post test. Missing data from Table 3 and 4 was the result of participant’s non-compliance with daily wearable tracker use for that week. Post hoc analysis with a Bonferroni adjustment revealed that steps/day was significantly increased from pre-intervention to weeks 3–4 (0.39 (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.54) mg/L, p < 0.0005), and from pre-intervention to post-intervention (0.68 (95% CI, 0.34 to 1.02) mg/L, p = 0.001), but not from weeks 3–4 to post-intervention (0.29 (95% CI, -0.01 to 0.59) mg/L, p = 0.054).

Discussion

Our study sought to answer whether a 10-week peer assisted telehealth intervention with the use of wearable devices would result in improved self-determined motivation, engagement in PA, and decreased adiposity, for adults with autism compared to having access to wearable devices and related resources only (control). Across the 10 weeks of the intervention, participants completing the PACT demonstrated improvement in both perceived PA and in steps per day, compared to participants in the control group, which is promising PA behavior for adults with ASD. The absence of change in the wait-list control participants indicates that simply providing a wearable device with written and verbal daily PA recommendations from PA Guidelines is not sufficient for initiation and sustained PA engagement for adults with ASD. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the combined efficacy of Fitbit wearable device use and a telehealth delivered PA program with peer-mentoring, tailored for adults with ASD, on PA self-determined motivation, steps per day, and adiposity.

Self-Determined Motivation

Although non-significant improvement in self-determined motivation, based on RAI scores, were observed in PACT, the inclusion of the SDT framework and its emphasis on autonomy, competence, and relatedness provided a foundation to foster motivation and engagement that resulted in improved PA among our cohort of adults with ASD. Similar to (Todd et al., 2019) which incorporated SDT with adults with ASD, PACT provided participant preferred activities to optimize skills attenuation (autonomy & competence), and facilitate social engagement (relatedness) via telehealth technology. Additionally, written and verbal instructions, fitness support pod leaders were able to provide live demonstrations and feedback on exercise execution during telehealth sessions. It is also important to highlight that the majority of participants in this study had at least moderate to high functional capabilities, and were independent with wearables and teleconference technology, the targeted exercises were designed to improve strength, muscular endurance, exercise engagement and autonomy.

Physical Activity

Improvement in PA engagement is critical for preventing chronic diseases, especially among vulnerable populations such as adults with ASD as they face limited opportunities for PA participation (Croen et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2017). Most participants in PACT started with lower than recommended subjective and objective PA levels, however, the median improvement for the entire group by week-10 of PACT suggests that behavior changes are feasible for adults with ASD. Although percentage of participants who achieved at least 8,000 steps per day did not change for the control group, the number of participants in the PACT group reaching 8,000 steps per day increased from 22 to 44% by 10 weeks. Furthermore, this study underscored early adulthood as an especially critical period of development among adults with ASD due to the potential for unmet health needs and disparities in access to appropriate care, health status (Young Adult Health and Well-Being, 2017) (Ames et al., 2021) (Nicolaidis et al., 2013). The secondary data analysis of the cohort who completed the PACT intervention suggests that the largest significant improvement in PA as measured by the Fitbit wearables is between baseline and week 10. Improvements in steps per day began by week 2, then plateaued in week 4. There were non-significant decrease in step per day between weeks 4 and 6, however, maintaining program fidelity throughout this period appears to be critical as the second-largest improvement in step activity occurred after week 6. The overall improvement in PA is consistent with other studies that used specific exercise program in people with ASD (LaLonde et al., 2014; Savage et al., 2022; Todd et al., 2019).

Obesity

Given that PACT program was not designed to target weight loss, no significant changes in the anthropometric measures were found. It is also important to acknowledge that scientific management of obesity is often conflicting and the emphasis on reducing weight have been further questioned, thus requiring further understanding from the medical and healthcare community. More specifically, in 2019, the United States Preventative Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommended weight loss for all individuals with obesity while the Health at Every Size (HAES) model of care treatment promotes health improvement through enjoyable PA and eating for well-being without a focus on weight loss with cited improvements in quality of life, psychological well-being, eating behaviors, and aerobic capacity with weight-neutral interventions, weight inclusivity, focusing on body acceptance rather than weight loss, embracing a more weight-neutral model (Curry et al., 2018; Dimitrov Ulian et al., 2018; Ulian et al., 2018). Additionally, disparities in access to health services is thought to contribute to preventable health behavior that perpetuates physical inactivity, poor weight management and related health risks. In addition, obesity related risk factors are further compounded among racial minority and special needs populations such as individuals with ASD (Hill et al., 2015; Matheson & Douglas, 2017). Future iterations of the PACT program would benefit from the inclusion of nutrition and healthy eating educational modules developed in collaboration with dietitians who have experience working with adults with ASD.

PACT Intervention

Although telehealth has been an integral part of acquiring health services, the COVID-19 pandemic catapulted this health service platform to more homes as the technology, familiarity and acceptance grows. The use of telehealth technology in PACT facilitated the delivery of PA health-literacy, socialization opportunities, and optimized functional movement in PACT participants while maintaining a sense of comfort, thus impacting PA behavior change and motivation. PACT study results also support previous findings on the utility of telemedicine to assess children with autism (Wagner et al., 2021) and more specifically, telerehabilitation by physical therapists, to deliver physical therapy related services to adults with varied chronic health conditions (Jette, 2021; Seron et al., 2021). From a health practitioner perspective, physical therapists perceive greater ease to health-care delivery via telehealth as they are able to adjust patient/client exercise, or progression of home exercise programs based on observed environmental factors, improved access and continuity of care in the setting of patient-specific barriers (i.e., distance, travel cost, time to follow-up, risk of COVID exposure), and overall patient-reported improvement and satisfaction (Miller et al., 2022). Furthermore, PACT incorporated interventional components similar to the Step It Up program which utilized Fitbits and coaching (Savage et al., 2022), and goal setting and reinforcement, as observed in the work of LaLonde et al. (LaLonde et al., 2014), which have demonstrated beneficial effects on weight and PA among adults with ASD. In contrast, the PACT program innovatively leveraged remote technology, telehealth, and online peer support, and thereby alleviating the burden on caregivers. Improvements in PA are supported by PACT participants preferences towards remote programming and likelihood to participant in PACT should it become available again (Tovin & Nunez-Gaunaurd, 2024). Our study's findings suggest that this shift towards leveraging telehealth approaches could offer a more sustainable solution for PA interventions among adults with ASD.

Autism and Race/Ethnic Diversity

The PACT study contributes to our understanding of PA engagement and delivery for adults with ASD of ethnic minority groups as 61% of PACT participants were of Hispanic ethnicity. Individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and children from low-income families receive less access to specialized services, educational services, and community services compared with higher-income and white families (Smith et al., 2020). Both racial/ethnic minorities and more recently, persons with a disability populations are designated as a health disparity populations (HealthyPeople2030, 2023). Furthermore, screening and preventive care for individuals with ASD, especially from racial and ethnic minority groups is critical as Black, Hispanic, and Asian Medicaid beneficiaries with ASD have been found to have higher odds of diabetes, hospitalized cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension, among other conditions (Schott et al., 2022). The prevalence of under-reporting of race and ethnicity data, in autism intervention research is concerning (Steinbrenner et al., 2022) and therefore accounting for race and ethnicity is of critical significance since systemic injustices, race and other demographic factors can be social determinants of health and may further contribute to negative health outcomes for individuals with ASD who are already at greater risk for adverse health outcomes (Bishop-Fitzpatrick & Kind, 2017). Telehealth delivered PA opportunities that may potentially improve access to health services such as PACT, may be especially beneficial for adults with ASD from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Peer Engagement in PACT

Finally, PACT’s peer-assisted telehealth delivery provided DPT students with the opportunity to hone additional skills and knowledge to better meet current healthcare demands. Previous research on medical and other health professional student learned outcomes support the utility and effectiveness of training in this rapidly advancing mode of healthcare delivery to optimize care for their future patient/clients, especially from underserved populations (Camhi et al., 2020; Serwe et al., 2020). Finally, findings from this study underscores the need for service mechanisms and delivery formats (i.e., telehealth) that meet diverse preferences and needs in order to facilitate access and engagement. While adults with ASD, share the same diagnosis of ASD, each adult with ASD presents with unique abilities and health service needs. A further understanding of health service preferences, access, and utilization can inform future health and wellness program development across the lifespan.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although all participants enrolled in this pilot study were recruited from a local autism registry, autism diagnosis and severity were self-reported and not confirmed with medical documentation or with a standardized clinical assessment. Therefore, interpretation of these pilot study findings may not be generalized, and instead limited to individuals with ASD who have autonomy with consumer technology and communication, as they were required to complete an online screening survey independently to participate in PACT. Moreover, recruitment of participants only from the local autism registry also limited racial/ethnic diversity to those who reside within the community. This pilot study included a large proportion of participants from Hispanic ethnicity which corresponded with the local ethic demographics. This limits inferences on the effectiveness of PACT to a more general population. As a pilot study, our low sample size of 18 participants, underpowered the study results.

Other limitations were a result of the methodology and study design. This pilot study design did not include subject follow-up after the post-test data collection. Therefore, long-term effects of PACT on PA were not examined and PA sustainability cannot be determined. Nevertheless, the findings of this pilot RCT supports additional study that includes longitudinal evaluation to examine long-term impact on PA for this population. Additionally, the lack of standardized assessment of physical function and functional mobility was a limitation and should be incorporated in larger trials and as these domains may moderate PA engagement. Lastly, as discussed in existing research on telehealth delivery of health services and wearable technology (Garcia et al., 2021a, b; Southey & Stoddart, 2021), challenges related to technology and user ability level were encountered such as difficulty syncing wearable with personal telephone and device charging. More specific challenges with technology and participant preferences for PACT are described in the feasibility study (Tovin & Nunez-Gaunaurd, 2024).

Finally, individuals with autism are unique in that their clinical presentations, co-morbidities, level of function across domains, personal and environmental factors, including their social determinants of health, vary across the spectrum as well. Therefore, future studies should examine these factors in relation to optimizing PA initiation and sustainability. Additionally, an evaluation of intervention modifications and strategies to augment participant engagement from varied autism spectrum severity and determining the optimal range for social-behavioral, cognitive, and physical functioning, mobility, and executive functioning that best benefits from a telehealth intervention is warranted. It is also important to identify when participants have reached their maximum potential with telehealth and whether the intervention duration influences PA maintenance or readiness to transition to an inclusive community-based PA program. Additionally, larger studies that facilitate participation from adults with ASD from underserved populations (racial/ethnic minority groups, individuals from low socioeconomic status and limited technology access) is critical as we address known health disparities among this population.

Conclusion

Findings support the benefits of a telehealth PA program that incorporates the use of peer support, wearable activity trackers and individualized PA/exercises via telehealth. Results from this study may inform the development of an optimal intervention to address physical inactivity for adults with ASD. Findings, although still emerging, encouragingly suggests that services via telehealth are equivalent or better to services face-to-face for some participants. Results support the benefits to using telehealth with adults with ASD. Future research should continue to explore the feasibility of both assessments and interventions via telehealth with those with ASD to make access to assessment services and interventions more feasible for families, while acknowledging the digital divide it could create.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (2013). (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Ames, J. L., Massolo, M. L., Davignon, M. N., Qian, Y., & Croen, L. A. (2021). Healthcare service utilization and cost among transition-age youth with autism spectrum disorder and other special healthcare needs. Autism, 25(3), 705–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320931268

Amireault, S., & Godin, G. (2015). The Godin-Shephard leisure-time physical activity questionnaire: Validity evidence supporting its use for classifying healthy adults into active and insufficiently active categories. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 120(2), 604–622. https://doi.org/10.2466/03.27.PMS.120v19x7

Bailey, R. R. (2019). Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 13(6), 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617729634

Bal, V. H., Wilkinson, E., White, L. C., Law, J. K., Consortium, T. S., Feliciano, P., & Chung, W. K. (2021). Early Pandemic Experiences of Autistic Adults: Predictors of Psychological Distress. Autism Research, 14(6), 1209–1219. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2480

Baranek, G. T., Little, L. M., Diane Parham, L., Ausderau, K. K., & Sabatos-DeVito, M. G. (2014). Sensory Features in Autism Spectrum Disorders. In Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, Fourth Edition. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118911389.hautc16

Barisic, A., Leatherdale, S. T., & Kreiger, N. (2011). Importance of frequency, intensity, time and type (FITT) in physical activity assessment for epidemiological research. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 174–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03404889

Bhat, A. N. (2021). Motor Impairment Increases in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder as a Function of Social Communication, Cognitive and Functional Impairment, Repetitive Behavior Severity, and Comorbid Diagnoses: A SPARK Study Report. Autism Research, 14(1), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2453

Bishop-Fitzpatrick, L., & Kind, A. J. H. (2017). A Scoping Review of Health Disparities in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(11), 3380–3391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3251-9

Blagrave, A. J., Colombo-Dougovito, A. M., & Healy, S. (2021). “Just Invite Us”: Autistic Adults’ Recommendations for Developing More Accessible Physical Activity Opportunities. Autism Adulthood, 3(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0055

Bremer, E., Crozier, M., & Lloyd, M. (2016). A systematic review of the behavioural outcomes following exercise interventions for children and youth with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(8), 899–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315616002

Buchanan, A. M., Miedema, B., & Frey, G. C. (2017). Parents’ Perspectives of Physical Activity in Their Adult Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Social-Ecological Approach. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 34(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2016-0099

Camhi, S. S., Herweck, A., & Perone, H. (2020). Telehealth Training Is Essential to Care for Underserved Populations: A Medical Student Perspective. Med Sci Educ, 30(3), 1287–1290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-020-01008-w

Caspersen, C. J., Powell, K. E., & Christenson, G. M. (1985). Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: Definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Reports, 100(2), 126–131.

CDC, C. f. D. C. P. (2022). Defining adult overweight & obesity. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved April 5, 2023 from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

Cho, A. B., Otte, K., Baskow, I., Ehlen, F., Maslahati, T., Mansow-Model, S., Schmitz-Hübsch, T., Behnia, B., & Roepke, S. (2022). Motor signature of autism spectrum disorder in adults without intellectual impairment. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7670. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10760-5

Chung, W. (2020). COVID-19 and its impact on autistic adults in the SPARK Community. SPARK. https://sparkforautism.org/discover_article/covid-19-and-its-impact-on-autistic-adults/

Clark, R. R., Fischer, A. J., Lehman, E. L., & Bloomfield, B. S. (2019). Developing and Implementing a Telehealth Enhanced Interdisciplinary Pediatric Feeding Disorders Clinic: A Program Description and Evaluation [Article]. Journal of Developmental & Physical Disabilities, 31(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-018-9652-7

Cousins, M., & Smyth, M. M. (2003). Developmental coordination impairments in adulthood. Human Movement Science, 22(4–5), 433–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2003.09.003

Croen, L. A., Zerbo, O., Qian, Y., Massolo, M. L., Rich, S., Sidney, S., & Kripke, C. (2015). The health status of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315577517

Curry, S. J., Krist, A. H., Owens, D. K., Barry, M. J., Caughey, A. B., Davidson, K. W., Doubeni, C. A., Epling, J. W., Jr., Grossman, D. C., Kemper, A. R., Kubik, M., Landefeld, C. S., Mangione, C. M., Phipps, M. G., Silverstein, M., Simon, M. A., Tseng, C. W., & Wong, J. B. (2018). Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama, 320(11), 1163–1171. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.13022

Deci EL, Ryan RM. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Springer Science+Business Media New York 1985. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Deci EL, Ryan RM. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.) https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_DeciRyan_PIWhatWhy.pdf

Dimitrov Ulian, M., Pinto, A. J., de Morais Sato, P., Benatti, F. B., Lopes de Campos-Ferraz, P., Coelho, D., Roble, O. J., Sabatini, F., Perez, I., Aburad, L., Vessoni, A., Fernandez Unsain, R., Macedo Rogero, M., Toporcov, T. N., de Sá-Pinto, A. L., Gualano, B., & Scagliusi, F. B. (2018). Effects of a new intervention based on the health at every size approach for the management of obesity: The "Health and Wellness in Obesity" study. PLoS One, 13(7), e0198401. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198401

Diaz, K. M., Krupka, D. J., Chang, M. J., Peacock, J., Ma, Y., Goldsmith, J., Schwartz, J. E., & Davidson, K. W. (2015). Fitbit®: An accurate and reliable device for wireless physical activity tracking. International Journal of Cardiology, 185, 138–140.

Dickinson, K., & Place, M. (2014). A Randomised Control Trial of the Impact of a Computer-Based Activity Programme upon the Fitness of Children with Autism. Autism Research and Treatment, 2014, 419653. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/419653

Downs, J., Blackmore, A. M., Wong, K., Buckley, N., Lotan, M., Elefant, C., Leonard, H., & Stahlhut, M. (2023). Can telehealth increase physical activity in individuals with Rett syndrome? A multicentre randomized controlled trial. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 65(4), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.15436

Edmunds, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Duda, J. L. (2008). Testing a self-determination theory-based teaching style intervention in the exercise domain. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(2), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.463

Fournier, K. A., Hass, C. J., Naik, S. K., Lodha, N., & Cauraugh, J. H. (2010). Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(10), 1227–1240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3

Garcia, J. M., Cathy, B. S., Garcia, A. V., Shurack, R., Brazendale, K., Leahy, N., Fukuda, D., & Lawrence, S. (2021a). Transition of a Judo Program from In-Person to Remote Delivery During COVID-19 for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Adv Neurodev Disord, 5(2), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-021-00198-7

Garcia, J. M., Leahy, N., Brazendale, K., Quelly, S., & Lawrence, S. (2021b). Implementation of a school-based Fitbit program for youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A feasibility study. Disability and Health Journal, 14(2), 100990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100990

Gibson, S., & Ashwell, M. (2020). A simple cut-off for waist-to-height ratio (0·5) can act as an indicator for cardiometabolic risk: Recent data from adults in the Health Survey for England. British Journal of Nutrition, 123(6), 681–690. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114519003301

Godin, G., & Shephard, R. J. (1997). Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Applied Sports Sciences

Gusmer, R. J., Bosch, T. A., Watkins, A. N., Ostrem, J. D., & Dengel, D. R. (2014). Comparison of FitBit® ultra to ActiGraph™ GT1M for assessment of physical activity in young adults during treadmill walking. The Open Sports Medicine Journal, 8, 11–15. https://benthamopen.com/contents/pdf/TOSMJ/TOSMJ-8-11.pdf

Hamm, J., & Yun, J. (2018). The motivational process for physical activity in young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Health Journal, 11(4), 644–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.05.004

HealthIT. (2017). What is telehealth? How is telehealth different than telemedicine?. Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Retrieved May 27, 2022 from https://www.healthit.gov/faq/what-telehealth-how-telehealth-different-telemedicine

Healy, S., Brewer, B., Laxton, P., Powers, B., Daly, J., McGuire, J., & Patterson, F. (2021). Brief Report: Perceived Barriers to Physical Activity Among a National Sample of Autistic Adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05319-8

Heyman, G. D., & Dweck, C. S. (1992). Achievement goals and intrinsic motivation: Their relation and their role in adaptive motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 16(3), 231–247.

Hill, A. P., Zuckerman, K. E., & Fombonne, E. (2015). Obesity and Autism. Pediatrics, 136(6), 1051–1061. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-1437

Hillier, A., Buckingham, A., & Schena, D., 2nd. (2020). Physical Activity Among Adults With Autism: Participation, Attitudes, and Barriers. Percept Mot Skills, 127(5), 874-890. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512520927560

Himes, J. H. (2009). Challenges of accurately measuring and using BMI and other indicators of obesity in children. Pediatrics, 124(Suppl 1), S3-22. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3586D

HealthyPeople2030. (2023). Health equity in Healthy People 2030 Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Retrieved December 20, 2023 from: https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-equity-healthy-people-2030

Jette, A. M. (2021). The promise and potential of telerehabilitation in physical therapy. Physical Therapy, 101(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab081

LaLonde, K. B., MacNeill, B. R., Eversole, L. W., Ragotzy, S. P., & Poling, A. (2014). Increasing physical activity in young adults with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(12), 1679–1684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.09.001

Lang, R., Koegel, L. K., Ashbaugh, K., Regester, A., Ence, W., & Smith, W. (2010). Physical exercise and individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(4), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.01.006

Lindgren, S., Wacker, D., Suess, A., Schieltz, K., Pelzel, K., Kopelman, T., Lee, J., Romani, P., & Waldron, D. (2016). Telehealth and Autism: Treating Challenging Behavior at Lower Cost. Pediatrics, 137 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S167–175. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-2851O

Lord, C., Charman, T., Havdahl, A., Carbone, P., Anagnostou, E., Boyd, B., Carr, T., de Vries, P. J., Dissanayake, C., Divan, G., Freitag, C. M., Gotelli, M. M., Kasari, C., Knapp, M., Mundy, P., Plank, A., Scahill, L., Servili, C., Shattuck, P., . . . McCauley, J. B. (2022). The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. Lancet, 399(10321), 271–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01541-5

Markland, D., & Tobin, V. (2004). A Modification to the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire to Include an Assessment of Amotivation. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 26(2), 191–196. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.26.2.191

Matheson, B. E., & Douglas, J. M. (2017). Overweight and Obesity in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): A Critical Review Investigating the Etiology, Development, and Maintenance of this Relationship. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 4(2), 142–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-017-0103-7

Messiah, S. E., Arheart, K. L., Luke, B., Lipshultz, S. E., & Miller, T. L. (2008). Relationship between body mass index and metabolic syndrome risk factors among US 8- to 14-year-olds, 1999 to 2002. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 153, 215–221.

Miller, M. J., Pak, S. S., Keller, D. R., Gustavson, A. M., & Barnes, D. E. (2022). Physical Therapist Telehealth Delivery at 1 Year Into COVID-19. Phys Ther, 102(11). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzac121

Mullan, E., Markland, D., & Ingledew, D. K. (1997). A graded conceptualisation of self-determination in the regulation of exercise behaviour: Development of a measure using confirmatory factor analytic procedures. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(5), 745–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00107-4

Narzisi, A., Muratori, F., Calderoni, S., Fabbro, F., & Urgesi, C. (2013). Neuropsychological profile in high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(8), 1895–1909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1736-0

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). (2011). Anthropometry procedures manual. Retrieved February 26, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_11_12/anthropometry_procedures_manual.pdf

Nichols, C., Block, M. E., Bishop, J. C., & McIntire, B. (2018). Physical activity in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: Parental perceptions of barriers and facilitators. Autism, 23(6), 1398–1407. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318810221

Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D., McDonald, K., Dern, S., Boisclair, W. C., Ashkenazy, E., & Baggs, A. (2013). Comparison of Healthcare Experiences in Autistic and Non-Autistic Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey Facilitated by an Academic-Community Partnership. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28(6), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2262-7

Ntoumanis, N., Ng, J. Y. Y., Prestwich, A., Quested, E., Hancox, J. E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Lonsdale, C., & Williams, G. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of self-determination theory-informed intervention studies in the health domain: Effects on motivation, health behavior, physical, and psychological health. Health Psychology Review, 15(2), 214–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1718529

Obrusnikova, I., & Cavalier, A. R. (2011). Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Participation in After-School Physical Activity by Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 23(3), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-010-9215-z

Paluch, A. E., Gabriel, K. P., Fulton, J. E., Lewis, C. E., Schreiner, P. J., Sternfeld, B., Sidney, S., Siddique, J., Whitaker, K. M., & Carnethon, M. R. (2021). Steps per Day and All-Cause Mortality in Middle-aged Adults in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. JAMA Network Open, 4(9), e2124516–e2124516. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24516

Pearson, O. R., Busse, M. E., van Deursen, R. W. M., & Wiles, C. M. (2004). Quantification of walking mobility in neurological disorders. QJM : Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians, 97(8), 463–475. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hch084

Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., George, S. M., & Olson, R. D. (2018). The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA, 320(19), 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14854

Ptomey, L. T., Lee, J., White, D. A., Helsel, B. C., Washburn, R. A., & Donnelly, J. E. (2021). Changes in physical activity across a 6-month weight loss intervention in adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12909

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Samdal, G. B., Eide, G. E., Barth, T., Williams, G., & Meland, E. (2017). Effective behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating in overweight and obese adults; systematic review and meta-regression analyses. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0494-y

Sandroff, B. M., Motl, R. W., Pilutti, L. A., Learmonth, Y. C., Ensari, I., Dlugonski, D., Klaren, R. E., Balantrapu, S., & Riskin, B. J. (2014). Accuracy of StepWatch™ and ActiGraph Accelerometers for Measuring Steps Taken among Persons with Multiple Sclerosis. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e93511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093511

Savage, M. N., Taber-Doughty, T., Brodhead, M. T., & Bouck, E. C. (2018). Increasing physical activity for adults with autism spectrum disorder: Comparing in-person and technology delivered praise. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 73, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.12.019

Savage, M. N., Tomaszewski, B. T., & Hume, K. A. (2022). Step It Up: Increasing Physical Activity for Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability Using Supported Self-Management and Fitbit Technology. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 37(3), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576211073700

Schott, W., Tao, S., & Shea, L. (2022). Co-occurring conditions and racial-ethnic disparities: Medicaid enrolled adults on the autism spectrum. Autism Research, 15(1), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2644

Seron, P., Oliveros, M.-J., Gutierrez-Arias, R., Fuentes-Aspe, R., Torres-Castro, R. C., Merino-Osorio, C., Nahuelhual, P., Inostroza, J., Jalil, Y., Solano, R., Marzuca-Nassr, G. N., Aguilera-Eguía, R., Lavados-Romo, P., Soto-Rodríguez, F. J., Sabelle, C., Villarroel-Silva, G., Gomolán, P., Huaiquilaf, S., & Sanchez, P. (2021). Effectiveness of telerehabilitation in physical therapy: A rapid overview. Physical Therapy, 101(6). https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab053

Serwe, K. M., Heindel, M., Keultjes, I., Silvers, H., & Stovich, S. (2020). Telehealth Student Experiences and Learning: A Scoping Review.

Smith, K. A., Gehricke, J.-G., Iadarola, S., Wolfe, A., & Kuhlthau, K. A. (2020). Disparities in Service Use Among Children With Autism: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics, 145(Supplement_1), S35-S46. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-1895G

Southey, S. J., & Stoddart, K. P. (2021). Clinical intervention with autistic adolescents and adults during the first two months of the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of clinicians and their clients. International Social Work, 64(5), 777–782. https://doi.org/10.1177/00208728211012462

Srinivasan, S. M., Pescatello, L. S., & Bhat, A. N. (2014). Current Perspectives on Physical Activity and Exercise Recommendations for Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorders. Physical Therapy, 94(6), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130157

Steinbrenner, J. R., McIntyre, N., Rentschler, L. F., Pearson, J. N., Luelmo, P., Jaramillo, M. E., Boyd, B. A., Wong, C., Nowell, S. W., Odom, S. L., & Hume, K. A. (2022). Patterns in reporting and participant inclusion related to race and ethnicity in autism intervention literature: Data from a large-scale systematic review of evidence-based practices. Autism, 13623613211072593. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211072593

Sullivan, G. M., & Feinn, R. (2012). Using Effect Size-or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4(3), 279–282. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-12-00156.1

Sullivan, A. N., & Lachman, M. E. (2016). Behavior Change with Fitness Technology in Sedentary Adults: A Review of the Evidence for Increasing Physical Activity. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00289

Thivel, D., Tremblay, A., Genin, P. M., Panahi, S., Rivière, D., & Duclos, M. (2018). Physical Activity, Inactivity, and Sedentary Behaviors: Definitions and Implications in Occupational Health. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 288. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00288

Todd, T., Miodrag, N., Colgate Bougher, S., & Zambom, A. Z. (2019). A Peer Mentored Physical Activity Intervention: An Emerging Practice for Autistic College Students. Autism Adulthood, 1(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2018.0051

Tomaszewski, B., Savage, M. N., & Hume, K. (2022). Examining physical activity and quality of life in adults with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 26(4), 1075–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/17446295211033467

Toth, L. P., Park, S., Springer, C. M., Feyerabend, M. D., Steeves, J. A., & Bassett, D. R. (2018). Video-recorded validation of wearable step counters under free-living conditions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 50(6), 1315–1322.

Tovin, M. M., & Nunez-Gaunaurd, A. (2024). Implementation of Peer-Assisted Physical Activity via Telehealth for Adults on the Autism Spectrum: A Mixed Methods Feasibility Study. Physical Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzae005

Ulian, M. D., Aburad, L., da Silva Oliveira, M. S., Poppe, A. C. M., Sabatini, F., Perez, I., Gualano, B., Benatti, F. B., Pinto, A. J., Roble, O. J., Vessoni, A., de Morais Sato, P., Unsain, R. F., & Baeza Scagliusi, F. (2018). Effects of health at every size® interventions on health-related outcomes of people with overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 19(12), 1659–1666. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12749

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. (2018). Retrieved on Feb 26, 2024 from: https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

Wagner, L., Corona, L. L., Weitlauf, A. S., Marsh, K. L., Berman, A. F., Broderick, N. A., Francis, S., Hine, J., Nicholson, A., Stone, C., & Warren, Z. (2021). Use of the TELE-ASD-PEDS for Autism Evaluations in Response to COVID-19: Preliminary Outcomes and Clinician Acceptability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(9), 3063–3072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04767-y

Weir, E., Allison, C., Ong, K. K., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021). An investigation of the diet, exercise, sleep, BMI, and health outcomes of autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 12(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-021-00441-x

WHO. (2017). Physical Activity Fact Sheet. Retrieved March 17, 2023 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity

Yarımkaya, E., Esentürk, O. K., İlhan, E. L., Kurtipek, S., & Işım, A. T. (2022). Zoom-delivered Physical Activities Can Increase Perceived Physical Activity Level in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Pilot Study. J Dev Phys Disabil, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-022-09854-9

Young Adult Health and Well-Being. (2017). A Position Statement of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(6), 758–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.021

Zheng, Z., Zhang, L., Li, S., Zhao, F., Wang, Y., Huang, L., Huang, J., Zou, R., Qu, Y., & Mu, D. (2017). Association among obesity, overweight and autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11697. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12003-4

Acknowledgements & Funding

The authors wish to thank the NSU and FIU DPT students for their commitment to the research study and parents/caregivers of participants for their unwavering support. This study was conducted without external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Nova Southeastern University Review Board (IRB # 2020–439) and an External IRB for oversight (TOPAZ Reference #110033) from Florida International University.

Informed Consent

Informed Consent were obtained from participants in this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nunez-Gaunaurd, A., Tovin, M. Promoting Physical Activity Through Telehealth, Peer Support, and Wearables: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Among Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil 36, 921–947 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09951-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-024-09951-x