Abstract

Family navigation (FN) and phone-based care coordination may improve linkages from primary care to community-based mental health referrals, but research on their differential impact is limited. This mixed-methods study compared FN and phone-based care coordination in connecting families to mental health services from primary care. Families of children (56.3% male, mean age = 10.4 years, 85.4% Black) were sequentially assigned to either receive FN through a family-run organization or phone-based coordination via the child psychiatry access program (CPAP). Caregiver-reported children’s mental health improved in both groups and both groups were satisfied with services. More families in the CPAP group had appointments made or completed (87%) than families in the FN group (71%) though the difference was not statistically significant. Future research with a larger sample that matches family needs and preferences (e.g., level and type of support) with navigation services would be beneficial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pediatric primary care clinicians (PCCs; e.g., pediatricians, nurse practitioners) play a critical role in identifying mental health concerns, which are experienced by approximately one in five youth (Foy & American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health, 2010; Kessler et al., 2005; Stagman & Cooper, 2010). The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated mental health problems and access to treatment among youth (Racine et al., 2021; Samji et al., 2022). Indeed, an increasing number of PCCs are identifying mental health concerns at routine well-child visits (Beers et al., 2017), as PCCs are often the first point of access for children with mental health concerns (Foy & American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health, 2010). While many PCCs report that they are increasingly comfortable with their role in the identification of mental health concerns and subsequent referral to a specialized mental health provider, many continue to report discomfort with providing in-office interventions themselves or treatment with psychiatric medications, with the exception of ADHD (Bettencourt et al., 2021; Heneghan et al., 2008; Horwitz et al., 2015; Stein et al., 2008). Additionally, some youth with more severe mental health concerns require specialized support outside of primary care due to the complexity or severity of their condition (Horowitz et al., 2015). Yet many (48–62%) youth referred for outpatient mental health services fail to present for their intake (Harrison et al., 2004; Ofonedu et al., 2017), despite families expressing a desire to connect to services (Harrison et al., 2004).

Theoretical and empirical models suggest several barriers to mental health engagement including the following: caregiver beliefs (e.g., social norms), motivation (e.g., caregiver priorities), skills and knowledge about help-seeking, environmental barriers (e.g., transportation), institutional/system-level factors (e.g., inadequate insurance cover for mental health services), caregiver well-being (e.g., stress, [lack of] social support), and child symptom functioning (Cyr et al., 2019; Foy & American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health, 2010; Harrison et al., 2004; Larson et al., 2013; McKay & Bannon, 2004; Ofonedu et al., 2017). Barriers to care may be even more pronounced for youth who have been historically underserved, such as those in the foster care and juvenile justice systems, immigrants, those who identify as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color), and those experiencing poverty (Stagman & Cooper, 2010).

Primary care practices and states have grappled with ways to increase engagement in mental health care in general and linkages to care following PCC referrals more specifically. Across many states, child psychiatry access programs (CPAPs) have been used to fill in gaps, gaining traction as an effective way to address mental health concerns among youth (Foy & American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health, 2010). Starting with the Massachusetts program in 2004, CPAPs now exist in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and 6 tribal communities and US territories (https://www.nncpap.org/map). Programs vary based on factors such as funding, geography, and existing child mental health infrastructure (Bettencourt & Plesko, 2020; Spencer et al., 2019), but generally aim to increase the ability of PCCs to directly address the psychiatric needs of their patients. Many CPAPs provide a core set of services that includes PCC training and education, rapid phone access to advice from child and adolescent mental health clinicians, and referral assistance. While many CPAPs address referral support by providing a cultivated list of referral options to the PCC (specific to the type of service needed, accepted insurance and wait time; Maryland Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care, n.d.), some programs provide care coordination directly to patients and families in recognition of the barriers many families face when navigating a complex mental health system (Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program, n.d.). Evaluations of CPAPs have been primarily descriptive in nature, with most studies describing high levels of PCP enrollment and utilization, high acceptability and feasibility, and improvements in PCPs’ confidence in addressing their patients’ mental health needs (Bettencourt & Plesko, 2020; Spencer et al., 2019).

To our knowledge, no studies have examined rates of connection from CPAPs to mental health services following referral from primary care to community-based resources nor are there studies specifically examining care coordination. We know of only two studies that have examined family satisfaction with CPAP services (Cama et al., 2020; Dvir et al., 2012). However, both studies focused on the Massachusetts program and one study focused on parent satisfaction with PCP’s use of MCPAP rather than on their experiences with care coordination to community-based resources (Cama et al., 2020). Dvir et al. (2012) reported high levels of parent satisfaction with MCPAP staff and services, though satisfaction with care coordination to community-based resources versus satisfaction with MCPAP psychiatry consultations was not delineated.

In addition to CPAPs, peer support models have been put forth as another way to increase linkages with recommended mental health services (Chinman et al., 2014). In this model, caregivers of children with mental health needs or knowledge of community-based resources (referred to as “navigators”) support families who are newer to the mental health system in accessing services and understanding the system of care. Navigators can potentially address many of the aforementioned barriers to accessing mental health care by reducing families’ sense of isolation, stress, and self-blame; helping families clarify their own needs; teaching skills, coaching families, modeling effective advocacy; personalizing the approach to accessing healthcare; and bridging the gap between providers and families (Chinman et al., 2014; Mullen et al., 2023). Peer navigation has been deemed an evidence-based model of care by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and many states and health plans are increasingly reimbursing for this service (Eiken & Campbell, 2008). While the use of navigators has been cited as a promising way to better connect families from primary care to mental health care (Acri et al., 2016; Godoy et al., 2019), research is limited. Notably, much of the research has focused on navigation for adult patients with chronic health concerns or serious mental illness (Ali-Faisal et al., 2017; Freeman & Rodriguez, 2011) and few studies on mental health navigation have used randomized control methodology (Waid et al., 2021).

Within a pediatric population, peer navigation research has focused more on management of chronic illness or broader developmental concerns rather than mental health concerns (Cavaleri et al., 2011; Hoagwood et al., 2010). For example, a systematic review of empirical studies examining navigation for youth referred to behavioral health services found only 8 studies (Petts et al., 2021), with four of the studies targeting developmental diagnostic assessments, including three that focused on autism (Feinberg et al., 2016, 2021; Roth et al., 2016) and one that focused on connection with Early Intervention (Guevara et al., 2016). Research examining the use of family navigation for children with autism has found that families are more likely to complete an autism diagnostic assessment (Feinberg et al., 2016, 2021), have greater likelihood of connection with recommended services after an autism diagnosis is made (Roth et al., 2016), and demonstrate decreased caregiver stress (Jamison et al., 2017). However, this body of research is limited in its focus on autism rather than on referrals from primary care to community-based mental health referrals more broadly. Another study focused on referral from primary care to Early Intervention found that use of a navigator was feasible and there were good rates of connection (83% initiated referral; Guevara et al., 2016). However, there was no use of control arm, the navigator did not have lived experience, and the focus was on Early Intervention rather than mental health referrals more broadly.

Sprecher et al. (2018) conducted a retrospective descriptive cohort analysis of patient navigation in an urban academic pediatric primary care practice and found that navigators were fully successful (65% of the time) or partially successful (21% of the time) in completing the referred task and closing the loop with the PCC. Referrals for help with logistical barriers (e.g., assistance with transportation) were more likely to be successful when compared with referrals for developmental concerns (e.g., Early Intervention), referrals to promote treatment adherence, or referrals focused on transition to adult care (Sprecher et al., 2018). However, there was no comparison group and referrals were for a broad range of issues and not specifically for mental health concerns. Pantell et al. (2020) randomly assigned caregivers of youth seen in primary care and urgent care clinics to either in-person navigation or control (provision of resource list) to address social needs and found that navigation was associated with decreased risk of hospitalization in the year following, but there were no differences in emergency department utilization. While promising, this study focused on social needs and not on mental health navigation specifically.

For children experiencing mental health concerns, several studies have documented the benefits of telephone-based family navigation (FN), including connection with mental health services, especially for families in which parents were highly strained (Kutash et al., 2011, 2013). However, participants were families of children enrolled in special education programs and findings may therefore not generalize outside of the school setting. In a sample of families with limited financial resources referred for mental health services (from various referral sources including but not limited to primary care) in three counties in Oregon, a FN program demonstrated high rates of initial connections to mental health services and increased family empowerment compared to a control group receiving usual care (Koroloff et al., 1996). Notably, this study also provided a cash fund to support families in accessing mental health services, which may have provided additional benefit to families in the navigation condition potentially confounding outcomes. Furthermore, the majority of families in this study were White (82%), which may limit generalizability of findings to a region with greater racial and ethnic diversity.

We know of no research examining navigation from pediatric primary care to community-based mental health referrals nor research comparing navigation to CPAP care coordination support. This study addresses the identified gaps in the literature by expanding on this knowledge base with an examination of how navigators can be used to enhance mental health referrals from pediatric primary care and how navigation compares to the phone-based care coordination provided in some CPAPs.

Objectives

This mixed-methods study had 3 primary aims: (1) Determine if FN was more effective than phone-based care coordination for accessing community-based mental health services following referral from primary care; (2) Describe changes in key outcome variables related to the child (e.g., improvements in mental health), caregivers (e.g., depression, perceived social support), and the help-seeking process (e.g., barriers to care) between groups 3 months after referral from primary care; and (3) Describe families’ perceptions of accessing mental health care with the support of a peer navigator or CPAP phone-based care coordinator via surveys and interviews. We hypothesized that receipt of FN would increase the likelihood of connection with care compared to phone-based care coordination.

Methods

Study Setting

The District of Columbia joined the growing list of states with a CPAP in 2015 to promote mental health within primary care with increased collaboration between PCCs and mental health providers and to improve the identification, evaluation, and treatment of child mental health problems. The DC CPAP, “DC MAP” (Mental Health Access in Pediatrics) offers core services including (1) real-time phone-based consultation for PCCs with a child mental health specialist, (2) a one-time in-person or telehealth patient visit with a psychiatrist as clinically indicated, (3) support for PCCs in identifying community treatment referrals, (4) direct phone-based follow-up support for families to support resource navigation, (5) technical assistance on implementing routine mental health screening within a pediatric primary care practice, and (6) education for PCCs on mental health topics. Clinical questions were directed to a team of child psychiatrists and psychologists, whereas intake calls and care coordination were provided by a team of non-clinical, bachelor or master’s level program staff.

When PCCs called the DC CPAP to inquire about community-based mental health resources for families, as part of standard of care, the Care Coordinator provided information directly to patients and/or their caregivers about these resources and then followed up with the family via telephone at regular intervals to support the family in accessing care. Separately within the District of Columbia there has been a focus on increasing peer navigation for families of children with mental health concerns. The DC CPAP partnered with a local family-run, not-for-profit organization founded and led by parents of children with mental health concerns, that offers mental health FN. Prior to the study, the organization was receiving referrals directly from the community, but was not regularly receiving referrals from PCCs or the local CPAP.

Participants

Caregivers of youth between one and 18 years of age referred for DC-based CPAP care coordination (i.e., PCC had requested that the family be provided with referral resources) from February 2017 to November 2018 were initially eligible to participate. The recruitment period, which had already been extended beyond initial planned recruitment dates, was limited due to funding and resource constraints. Families were excluded from participation if the caregiver was not the custodial caregiver, the caregiver was younger than 18 years of age, the family did not reside in DC, or the caregiver was not comfortable completing surveys and interviews in English.

Recruitment and Informed Consent

Families who met eligibility criteria were asked via phone by the CPAP Care Coordinator if they wanted to learn more about the study. Research staff then contacted interested and eligible families via phone to provide further information, obtain informed consent, and set up a time to complete the baseline questionnaires. Caregivers were given the option of completing assessments at their home, at a public location (e.g., library), or at the hospital. They were compensated for their time in completing assessment measures/interviews.

Group Assignment and Intervention Descriptions

Participants were assigned alternately to the CPAP phone-based care coordination or FN groups. Immediately after completing informed consent and baseline surveys, families were informed of their group assignment and the CPAP team and FN team were notified accordingly so that they could follow up with the family to provide referral information and family support.

Family Navigation Group: Description of Services

Caregivers in the FN group could contact the navigator at any time, though navigators aimed to contact caregivers every few weeks when they did not hear from families to ensure regular contact. Caregivers and Navigators were able to communicate in-person, via phone (calls/texts), or via email depending on caregiver preferences and needs. Most FN family contact was in-person with sessions typically lasting an hour in length. While Navigators aimed to assist families in connecting with specific mental health resources to which they had been referred, they also were able to support families more broadly. For example, Navigators could support caregivers in accessing additional services that may be relevant to their child’s mental health (e.g., housing). Navigators working at the family-run organization, who have a minimum of a high school diploma or GED, all have “lived experience” in navigating youth mental health and/or substance use disorder systems. Navigators receive formal external trainings (e.g., local Department of Behavioral Health Certified Peer Training program, Mental Health First Aid and Recovery Coach trainings) as well as internal training and ongoing support and coaching within the organization from licensed clinicians. Navigators tend to have small caseloads (7–10 families) so that they can spend up to several hours per week with families if needed.

Child Psychiatry Access Program Group: Description of Services

At the time of the study, families referred to CPAP care coordination services received email or phone outreach from the Care Coordinator with information about mental health resources (e.g., agency telephone numbers). Following the initial contact, the Care Coordinator then attempted to contact the family 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months post-referral. During these calls, the Care Coordinator supported families in their efforts to access care, though typically this was limited to providing referral information again. Care Coordinators had advanced degrees (e.g., bachelor’s or master’s degrees) though did not have formal clinical training. During the course of the study, they maintained a relatively small caseload similar to that of the FN group (7–10 families).

Procedure

Participants completed a caregiver-report baseline assessment following informed consent (prior to group assignment) and a post-intervention assessment 3 months later. Families were notified about group assignment upon completion of informed consent and gathering of baseline assessments. Information about family contact with the mental health agency was gathered during each contact between the family by either the Care Coordinator or the Navigator depending on group assignment. Participants also completed a brief interview about their experiences trying to access mental health care at the end of the study. Quantitative data were entered into REDCap (Harris et al., 2009, 2019), a secure, web-based data capture application. Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and imported into Dedoose for analysis (Dedoose Version 9.0.17, 2021).

Measures

Caregivers completed questions about demographic characteristics for their child (e.g., race, ethnicity) and for themselves (e.g., parent education level). This included a question about the total number of ACES (Adverse Childhood Experiences) caregivers had experienced (range 1–10; Felitti et al., 1998). ACEs reflect children’s experiences with negative life events, such as family conflict, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. The ACEs questionnaire has acceptable internal consistency and test–retest reliability (Dube et al., 2004).

Family connection with mental health services was measured by whether the family had contact with any of the mental health agencies to which they were referred with the opportunity to indicate the nature of the contact (e.g., seen for a visit, on a waitlist). These data were gathered during calls between the family and either the Care Coordinator or Navigator and during endpoint interviews and questionnaires.

Parent perceptions of children’s mental health were assessed using several 5-point Likert scale questions developed by the study team focused on overall child mental health (1-excellent to 5-poor), child mental health changes (1-much better to 5-much worse), and concern about child mental health (1-not at all worried to 5-very worried).

Barriers to Children’s Mental Health Care (Larson et al., 2013), a 23-item survey that uses 6-point Likert scale questions (rating the extent to which they consider something a problem and agree with statements) was used to assess caregiver perceptions of mental health treatment and potential barriers in seeking mental health care, including tangible barriers (e.g., transportation problems, difficulty navigating resources; “The clinic is too far away from my home”) and intangible barriers (e.g., stigma, fears about medications; “I would be embarrassed if my family and friends found out I was taking my child to the mental health center”). Subscale reliability is adequate (Cronbach alphas > 0.7; Larson et al., 2013).

Parental self-efficacy was measured using the eight-item efficacy subscale from the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale (Johnston & Mash, 1989). Parents rate each item (e.g., “Being a parent is manageable, and any problems are easily solved”) using a 6-point Likert-type scale (from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree). Previous studies have demonstrated strong reliability and validity (Ohan et al., 2000; Rogers & Matthews, 2011). Internal consistency of this scale is good across both mothers (0.68) and fathers (0.74).

Caregiver perceptions of social support were measured with the widely used Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet et al., 1988), which has been demonstrated to have good internal reliability (Osman et al., 2014). This 12-item scale uses a 7-point Likert scale (Very Strongly Disagree to Very Strongly Agree) to explore social support from family, friends, and significant others. The scale's psychometric properties, including internal consistency (r = 0.85) and test–retest reliability (alpha = 0.88), are good.

Parental stress was assessed via two items (“I feel too stressed to enjoy my child” and “I get more frustrated than I want to with my child's behavior”) that are included on the Early Childhood Screening Assessment (Gleason et al., 2010). These items have been validated by the US Preventative Health Task Force to evaluate parental stress. Internal reliability of the scale is good (0.76; Gleason et al., 2010).

Parental depression was assessed via the 2-item Patient-Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2; Spitzer et al., 1999), which assesses depression symptoms over the previous 2 weeks (Kroenke et al., 2003; Staples et al., 2019). The widely used tool has strong psychometric properties, including 87% sensitivity and 78% specificity for Major Depressive Disorder and good internal consistency (0.86–0.89; Löwe et al., 2004).

Interviews were conducted by trained independent interviewers and lasted approximately 20 min. Interview guides used 20 semi-structured questions focused on perspectives on mental health (e.g., “How do you think other people in your family and community might react to you taking your child to the children’s mental health center?”), mental health integration in primary care (e.g., “Do you feel like your PCP plays an active role in getting your child the help they need?”), families’ experiences with trying to access mental health services (e.g., “Tell me about your experiences trying to access mental health services for your child or yourself. What were some positive or helpful aspects? What were some difficult or challenging aspects?”), and their experiences working with either the Navigator or CPAP Care Coordinator (e.g., “What could be done to improve the experience?”).

Data Analyses

This mixed-methods study employed separate strategies to address quantitative and qualitative aims. Quantitative analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 with two-sided tests using a p value of < 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A power analysis conducted prior to study implementation assumed a power of 0.80, α = 0.05, and a 30% greater rate of mental health appointment completion for the FN group compared to the CPAP group which yielded a sample size of 38 families per group at the time of follow-up. Independent relationships between variables at baseline and month 3 (e.g., child and caregiver well-being variables such as parent depression and social support and child mental health improvements) as well as the difference between the control and intervention groups (e.g., mental health referral completion status) were examined using Chi-Square, Fishers Exact Test, McNemar’s Chi-Square, Wilcoxon Rank Sum, and Wilcoxon Sign Rank significance tests. Intangible and tangible barriers to care were summed for each individual and the significance of the difference between baseline and month 3 was assessed using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, and the significance of the difference between intervention and control was assessed using the Wilcoxon Sign Rank test. These analyses were selected based on the nature of data collected (e.g., continuous versus categorical variables) and they accounted for repeated measures.

Qualitative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Verbatim interview transcripts were analyzed using Dedoose qualitative data analysis software (Dedoose Version 9.0.17, 2021). We used constant comparative qualitative analysis, an inductive, iterative process exemplified by simultaneous data collection and analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Initially, codes were induced from line-by-line analysis using the participants’ words to name codes. Codes were created based on qualitative interviews with families describing their perceptions of mental health, barriers and facilitators in accessing care, and satisfaction with FN or CPAP services. Codes were then grouped based on content similarities (Thorne, 2008). Informational redundancy (i.e., not hearing new data from caregivers) was achieved after completing analysis of all the interviews. The coding scheme was developed jointly by several of the authors (LG, RW, LD, HF). Coding revisions were made using consensus agreement. In place of formal reliability analyses due to the small sample size, every interview was double coded to ensure consensus was reached.

Results

Study Participants

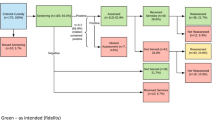

Figure 1 provides information about families approached and recruited into the study, as well as data about family completion and attrition. Of the 48 families who completed baseline questionnaires, 75% (n = 36) completed endpoint questionnaires and/or an interview at 3-months follow-up (62.5% from the CPAP group, n = 15; and 87.5% from the FN group, n = 21). Of the 48 participating families, we found no significant difference in the demographic characteristics of those who completed the study and those who did not complete the study. Demographic variables are described in Table 1. Child participants were 10.4 years old on average (SD = 3.8 years), 56.3% (n = 27) were boys, 87.5% (n = 42) identified the child’s race as Black/African American, and 10.0% (n = 5) identified the child’s ethnicity as Hispanic/Latinx. Most of the children (76.3%; n = 29) had public insurance. Caregivers were predominately biological mothers (92%) and they reported experiencing an average of four Adverse Childhood Experiences. There were no significant differences between the CPAP group and FN group in terms of demographic characteristics.

Family Connection with Mental Health Services

Of the 32 families with known referral status information, 78% (n = 25) made and completed appointments with mental health resources. Families in the CPAP group (87%) were more likely to have appointments made and completed than families in the FN group (71%), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.090).

Child and Caregiver Well-Being

Child and caregiver well-being variables are described in Table 2. There were no significant differences in caregiver-reported responses to a question about their child’s Overall Mental Health from baseline to follow-up, though there was a trend toward significant changes: baseline Median response = 4 (Fair) vs follow-up Median response = 3 (Good), p = 0.071. Caregivers reported improvements in children’s mental health from baseline to follow-up (p = 0.02) in response to a question about changes in their child’s mental health status (Median response at baseline = 3, About the Same vs Median response at 3 months follow-up = 2, A Little Better), though there were no significant differences between the CPAP and FN groups. There were no differences in caregiver-reported social support, efficacy, stress, or depression nor in caregiver-reported concern about child mental health across the study period or between groups.

Help-Seeking

Help-seeking variables are described in Table 3. Families in both groups reported significant improvement in having the information needed to manage their child’s mental health (p = 0.014) and there was a trend toward increases in family reports of being given information about treatment options (p = 0.096), though there were no significant differences between groups. There were significant decreases in intangible barriers to help-seeking over the course of the study (p = 0.016) and there was a trend in decreases in tangible barriers from baseline to follow-up (p = 0.054). There were no significant changes across the study period or between groups in several other variables, such as whether the family got the professional help they wanted, the efficacy of any treatment received, and the difficulty of getting treatment.

Qualitative Data Results

Family experiences with either CPAP or FN are described in Table 4. Families in both groups reported positive experiences about their relationship with the professional (i.e., the Navigator or CPAP phone-based Care Coordinator) with whom they worked and the focus and approach of the work. Families in the FN group reported a higher degree of overall satisfaction than families in the CPAP group (p = 0.037), though across both groups, high levels of satisfaction were reported.

Tables 5 and 6 summarize qualitative findings. At some point during the interview, the majority of families expressed neutral (80.0%) and/or negative (65.7%) attitudes or perceptions related to past experiences with mental health care, with only a quarter of families (25.7%) expressing positive attitudes, perceptions, or previous experiences. Barriers and facilitators of accessing mental health care were coded into different categories. It was then noted whether the family had indicated that the barrier or facilitator was something perceived to be an issue for families broadly (coded as “community” access barrier or facilitator) or something perceived to be an access barrier or facilitator for their individual family (coded as “personal” access barrier or facilitator). While about a third of families described their own persistence and prioritization of help-seeking (i.e., value [or lack thereof] caregivers place on accessing mental health services, particularly in relation to other competing priorities, perseverance/motivation [or lack thereof] in trying to access resources) to be both a community (34.3%) and a personal (34.3%) access barrier, over half of participating families (54.3%) expressed their persistence and prioritization of mental health issues as a facilitator in their access to care. One family described their persistence in obtaining mental health care stating, “All I know is I guess I was on top of it and they see that it was a problem also and instead of letting it get worse, we addressed the needs so it could get better.” The majority of families (67.1%) noted they had personal difficulties related to the mental health provider’s availability (e.g., not offering evening or flexible times) and other characteristics of services provided (e.g., long waitlists, not accepting new patients, limited patient age range). More families perceived education and knowledge of mental health issues to be a community access barrier to mental health care (37.1%) than to be a personal barrier (17.1%) that they had experienced. Families also cited external factors, such as financial status (20.0%), insurance issues (20.0%), and transportation/distance from resource (20.0%) as obstacles to their own personal access to care. In qualitative interviews, almost all families (88.6%) discussed favorable views about their PCC, expressing feelings of support, trust, and comfort. One family reported that their experience with their PCC was “very positive, and she reassured me that it's not an isolated situation. That many children have those types of issues, so she let me know that I wasn't alone.”

Overall, the majority of families discussed positive experiences receiving either FN (84.2%) or CPAP care (87.5%) during their interviews. Although the majority of families expressed positive experiences with both groups, over half (52.6%) of the families in the FN group expressed at least one unfavorable experience with the program (e.g., inconsistent access to the Navigator). Families in the CPAP group did not express any negative experiences with the program. Furthermore, the majority of families receiving CPAP services described a positive perception or experience with help-seeking (81.3%) during the interviews. Speaking on their experience with the program, a family in the CPAP group stated, “I appreciate her … following-up, the contacting, kind of checking-in here and there, seeing how everything goes, do I need anything, anything like that.” Only about half (57.9%) of the families receiving FN services described a positive experience with help-seeking. Many CPAP families cited service or provider availability (56.3%) and good coordination or follow-up (68.8%) as a facilitator to receiving services. In contrast, fewer FN families cited both service and provider availability (21.1%) and good coordination (31.6%) as an access facilitator.

Discussion

This study focused on ways to improve connection with mental health services following referral from primary care. The findings overall demonstrated the potential benefit that either phone-based care coordination or family navigation can play in accessing services. Follow-up connection rates in the present study (78% overall) were higher than prior literature on unassisted follow-up (48–62%; Harrison et al., 2004; Ofonedu et al., 2017). While families in the CPAP group (87%) were more likely to have appointments made and completed than families in the FN group (71%), the difference was not statistically significant and in the opposite direction from what we had hypothesized. In addition, families in both groups reported significant increases in their knowledge of how to address their children’s mental health problems, and both groups reported that the assistance they received had reduced barriers to receiving care, which is consistent with some other studies on navigation (e.g., Feinberg et al., 2021; Koroloff et al., 1996). Families in both groups reported positive changes in some key child and family well-being factors from baseline to follow-up, such as improvements in children’s mental health status, with no significant differences between the CPAP and FN groups.

Qualitative findings elucidated help-seeking processes and strengthen the limited research examining family outcomes and satisfaction following receipt of care coordination services (Bettencourt & Plesko, 2020). Families in both the CPAP and FN groups reported positive experiences and high levels of satisfaction with the professional with whom they worked via survey questions and interviews. This compares favorably to prior studies of caregiver satisfaction with child mental health access programs (Cama et al., 2020; Dvir et al., 2012). However, this is the first study to our knowledge that examined satisfaction with direct care CPAP coordination services specifically. Prior research has either been limited to survey responses (Dvir et al., 2012) or was gathered via interview but was similarly focused on close-ended responses and did not incorporate extensive open-ended qualitative data (Cama et al., 2020). Moreover, prior research was focused on satisfaction with CPAPs more broadly and not with care coordination services specifically.

While follow-up interviews with participating families found many positive reports about both forms of assistance, there was more variability in feedback among families in the FN group. Given the range of navigation options (e.g., team composition, types of supports offered), it could be helpful to match family needs and preferences with service type (Godoy et al., 2019). For example, some families may desire and benefit from peer support (e.g., those who prefer more support or who may have experienced previous difficulties trying to access care), whereas others may prefer phone-based Care Coordination alone. Furthermore, differences have been found in the appropriateness and acceptability of models of care depending on the youth’s presenting concern, thus highlighting the need to gather preliminary information about the child and family prior to matching families with a coordination service type (Spencer et al., 2019). Future research that assesses how to best match family needs and preferences (e.g., prior experiences trying to access care, level and type of support family desires) with navigation services could be beneficial.

This study should be understood in light of several limitations that can be addressed in future research. Our sample size was small (despite extending enrollment for seven additional months) and underpowered to detect potentially meaningful differences across our study outcomes. Additionally, our sample was limited to families who we could reach and enroll in the study and may therefore not generalize to a wider spectrum of families. We were unable to obtain endpoint data for 25% of families, including a significantly higher proportion of families in the FN group. While there were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between those who completed and did not complete endpoint data, dropout rates limit our ability to draw conclusions for families who may be at most risk of not connecting with mental health resources. The small sample size also prevented us from examining characteristics of specific navigators, nesting data by navigators, and examining potential mediators and moderators of change, which would be important to do in future research. Prior research with both parents of young children (Diaz-Linhart et al., 2016; Jamison et al., 2017) and with adults (Corrigan et al., 2017) suggests that the potential benefits of navigation may be more robust after the first several months. Thus, our study was limited by the 3-month follow-up period and future research that examines outcomes over a longer period (e.g., 6–12 months) would be beneficial.

We compared phone-based care coordination with FN provided from a particular organization in Washington, DC. The nature of FN services offered and the context for navigating services are limited and may therefore not be generalizable to those receiving services through another organization or outside of DC. Future work that includes other FN models or looks at connection with services in other geographic areas will be beneficial. Additionally, future research should expand upon the use of FN models targeting populations with specific mental health concerns (e.g., autism spectrum disorder; Broder-Fingert et al., 2020). Our study was limited to families who could respond to questionnaires and surveys in English, which limits generalizability. Future research that includes a broader spectrum of participants and can speak to the unique challenges of navigating mental health services when a caregiver’s primary language is not English would be beneficial.

Despite these limitations, lessons can be learned from these results. Many families struggle to connect with community-based mental health services following referral from primary care settings. This study documented several benefits to families working with a phone-based care coordinator or family navigator, which may be helpful in efforts to increase family connection with mental health services and ultimately lead to improvements in child and family well-being. Our findings suggest a benefit from either CPAPs providing direct phone-based care coordination to families or connection with local family navigation services. In this study, we were unable to compare either of these interventions to provision of a mental health resource list alone, which is standard of care for some CPAPs. Given prior research studies showing live navigation to be superior to written resources in some settings (Pantell et al., 2020), CPAPs may consider providing more intensive follow-up support to at least a subset of families. Our findings are especially relevant as access to CPAPs continues to expand and states may be increasingly relying on CPAPs to address gaps in pediatric mental health care.

Data Availability

N/A.

Code Availability

N/A.

References

Acri, M., Hooley, C. D., Richardson, N., & Moaba, L. B. (2017). Peer models in mental health caregivers and families. Community Mental Health Journal, 53, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-016-0040-x

Ali-Faisal, S. F., Colella, T. J. F., Medina-Jaudes, N., & Benz Scott, L. (2017). The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(3), 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.014

Beers, L. S., Godoy, L., John, T., Long, M., Biel, M. G., Anthony, B., Mlynarski, L., Moon, R., & Weissman, M. (2017). Mental health screening quality improvement learning collaborative in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics, 140(6), e20162966. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2966

Bettencourt, A. F., Ferro, R. A., Williams, J. L., Khan, K. N., Platt, R. E., Sweeney, S., & Coble, K. (2021). Pediatric primary care provider comfort with mental health practices: A needs assessment of regions with shortages of treatment access. Academic Psychiatry, 45(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-021-01434-x

Bettencourt, A. F., & Plesko, C. M. (2020). A systematic review of the methods used to evaluate child psychiatric access programs. Academic Pediatrics, 20(8), 1071–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.07.015

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Broder-Fingert, S., Stadnick, N. A., Hickey, E., Goupil, J., Lindhart, Y. D., & Feinberg, E. (2020). Defining the core components of family navigation for autism spectrum disorder. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319864079

Cama, S., Knee, A., & Sarvet, B. (2020). Impact of child psychiatry access programs on mental health care in pediatric primary care: Measuring the parent experience. Psychiatric Services, 71(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201800324

Cavaleri, M. A., Olin, S. S., Kim, A., Hoagwood, K. E., & Burns, B. J. (2011). Family support in prevention programs for children at risk for emotional/behavioral problems. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(4), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0100-9

Chinman, M., George, P., Dougherty, R. H., Daniels, A. S., Ghose, S. S., Swift, A., & Delphin-Rittmon, M. E. (2014). Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(4), 429–441. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300244

Corrigan, P. W., Pickett, S., Schmidt, A., Stellon, E., Hantke, E., Kraus, L., Dubke, R., & The Community Based Action Research Team. (2017). Peer navigators to promote engagement of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness in primary care. Psychiatry Research, 255, 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.020

Cyr, M. E., Etchin, A. G., Guthrie, B. J., & Benneyan, J. C. (2019). Access to specialty healthcare in urban versus rural US populations: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Services Research, 19, 974. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4815-5

Dedoose. (2021). Dedoose version 9.0.17, cloud application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. www.dedoose.com.

Diaz-Linhart, Y., Silverstein, M., Grote, N., Cadena, L., Feinberg, E., Ruth, B. J., & Cabral, H. (2016). Patient navigation for mothers with depression who have children in Head Start: A pilot study. Social Work in Public Health, 31(6), 504–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2016.1160341

Dube, S. R., Williamson, D. F., Thompson, T., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Assessing the reliability of retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences among adult HMO members attending a primary care clinic. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(729–737), 7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2003/08/009

Dvir, Y., Wenz-Gross, M., Jeffers-Terry, M., & Metz, W. P. (2012). An assessment of satisfaction with ambulatory child psychiatry consultation services to primary care providers by parents of children with emotional and behavioral needs: The Massachusetts child psychiatry access project university of Massachusetts parent satisfaction study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00007

Eiken, S., & Campbell, J. (2008). Medicaid coverage of peer support for people with mental illness: Available research and state examples. http://www.advancingstates.org/sites/nasuad/files/hcbs/files/150/7485/PeerSupport11-6.pdf

Feinberg, E., Abufhele, M., Sandler, J., Augustyn, M., Cabral, H., Chen, N., Diaz-Linhart, Y., Levesque, Z. C., Aebi, M., & Silverstein, M. (2016). Reducing disparities in timely autism diagnosis through family navigation: Results from a randomized pilot trial. Psychiatric Services, 67(8), 912–915. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500162

Feinberg, E., Kuhn, J., Sandler Eilenberg, J., Levinson, J., Patts, G., Cabral, H., & Broder-Fingert, S. (2021). Improving family navigation for children with autism: A comparison of two pilot randomized controlled trials. Academic Pediatrics, 21(2), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.04.007

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Foy, J. M., American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health. (2010). Enhancing pediatric mental health care: Report from the American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Mental Health. Introduction. Pediatrics, 125(3), S69-74. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0788C

Freeman, H. P., & Rodriguez, R. L. (2011). History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer, 117(15 Suppl), 3539–3542. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26262

Godoy, L., Hodgkinson, S., Robertson, H. A., Sham, E., Druskin, L., Wambach, C. G., Beers, L. S., & Long, M. (2019). Increasing mental health engagement from primary care: The potential role of family navigation. Pediatrics, 143(4), e20182418. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2418

Gleason, M. M., Zeanah, C. H., & Dickstein, S. (2010). Recognizing young children in need of mental health assessment: Development and preliminary validity of the early childhood screening assessment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 31(3), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20259

Guevara, J. P., Rothman, B., Brooks, E., Gerdes, M., McMillon-James, F., & Yun, K. (2016). Patient navigation to facilitate early intervention referral completion among poor urban children. Families, Systems, & Health, 34(3), 281–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000207

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Harrison, M. E., McKay, M. M., & Bannon, W. M. (2004). Inner-city child mental health service use: The real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:comh.0000022732.80714.8b

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., McLeod, L., Delacqua, G., Delacqua, F., Kirby, J., Duda, S. N., & REDCap Consortium. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Heneghan, A., Garner, A. S., Storfer-Isser, A., Kortepeter, K., Stein, R. E., & Horwitz, S. M. (2008). Pediatricians’ role in providing mental health care for children and adolescents: Do pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists agree? Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29(4), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31817dbd97

Hoagwood, K. E., Cavaleri, M. A., Olin, S. S., Burns, B. J., Slaton, E., Gruttadaro, D., & Hughes, R. (2010). Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5

Horwitz, S. M., Storfer-Isser, A., Kerker, B. D., Szilagyi, M., Garner, A., O’Connor, K. G., Hoagwood, K. E., & Stein, R. E. (2015). Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial problems: Changes from 2004 to 2013. Academic Pediatrics, 15(6), 613–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.006

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Jamison, J. M., Fourie, E., Siper, P. M., Trelles, M. P., George-Jones, J., Buxbaum Grice, A., Krata, J., Holl, E., Shaoul, J., Hernandez, B., Mitchell, L., McKay, M. M., Buxbaum, J. D., & Kolevzon, A. (2017). Examining the efficacy of a family peer advocate model for Black and Hispanic caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(5), 1314–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3045-0

Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1802_8

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Koroloff, N. M., Elliott, D. J., Koren, P. E., & Friesen, B. J. (1996). Linking low-income families to children’s mental health services. An outcome study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 4(1), 2–11.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41(11), 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., Green, A. L., & Ferron, J. M. (2011). Supporting parents who have youth with emotional disturbances through a parent-to-parent support program: A proof of concept study using random assignment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38, 412–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0329-5

Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., Green, A. L., & Ferron, J. (2013). Effectiveness of the parent connectors program: Results from a randomized controlled trial. School Mental Health, 5, 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-013-9106-4

Larson, J., dosReis, S., Stewart, M., Kushner, R., Frosch, E., & Solomon, B. (2013). Barriers to mental health care for urban, lower income families referred from pediatric primary care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(3), 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0389-1

Löwe, B., Kroenke, K., & Gräfe, K. (2004). Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 58(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006

Maryland Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care (BHIPP). (n.d.). Consultation warmline. https://mdbhipp.org/consultation-warmline.html

Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP). (n.d.). MCPAP services. https://www.mcpap.com/Provider/McPAPservice.aspx

McKay, M. M., & Bannon, W. M. (2004). Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 13(4), 905–921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001

Mullen, J. N., Levitt, A., & Markoulakis, R. (2023). Supporting individuals with mental health and/or additions issues through patient navigation: A scoping review. Community Mental Health Journal, 59, 35–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-022-00982-2

National Network of Child Psychiatry Access Programs. (n.d.). https://www.nncpap.org/map

Ofonedu, M. E., & Belcher, H. M. E., Budhathoki, C., & Gross, D. A. (2017). Understanding barriers to initial treatment engagement among underserved families seeking mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 863–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0603-6

Ohan, J. L., Leung, D. W., & Johnston, C. (2000). The parenting sense of competence scale: Evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 32(4), 251–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087122

Osman, A., Lamis, D. A., Freedenthal, S., Gutierrez, P. M., & McNaughton-Cassill, M. (2014). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Analysis of internal reliability, measurement invariance, and correlates across gender. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.838170

Pantell, M. S., Hessler, D., Long, D., Alqassari, M., Schudel, C., Laves, E., Velazquez, D. E., Amaya, A., Sweeney, P., Burns, A., Harrison, F. L., Adler, N. E., & Gottlieb, L. M. (2020). Effects of in-person navigation to address family social needs on child health care utilization: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e206445. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6445

Petts, R. A., McLain, M. B., Azad, G., & Shahidullah, J. D. (2021). System navigation models to facilitate engagement in pediatric behavioral health services: A systematic review. Families, Systems, & Health, 39(4), 618–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000643

Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

Rogers, H., & Matthews, J. (2011). The parenting sense of competence scale: Investigation of the factor structure, reliability, and validity for an Australian sample. Australian Psychologist, 39(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060410001660380

Roth, B. M., Kralovic, S., Roizen, N., Spannagel, S. C., Minich, N., & Knapp, J. (2016). Impact of autism navigator on access to services. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 37(3), 188–195. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000261

Samji, H., Wu, J., Ladak, A., Vossen, C., Stewart, E., Dove, N., Long, D., & Snell, G. (2022). Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 27(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12501

Spencer, A. E., Platt, R. E., Bettencourt, A. F., Serhal, E., Burkey, M. D., Sikov, J., Vidal, C., Stratton, J., Polk, S., Jain, S., & Wissow, L. (2019). Implementation of off-site integrated care for children: A scoping review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 27(6), 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/HRP.0000000000000239

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., & Williams, J. B. (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(18), 1737–1744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

Sprecher, E., Conroy, K., Chan, J., Lakin, P. R., & Cox, J. (2018). Utilization of patient navigators in an urban academic pediatric primary care practice. Clinical Pediatrics, 57(10), 1154–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922818759318

Stagman, S. M., & Cooper, J. L. (2010). Children’s mental health: What every policymaker should know. http://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:126203

Staples, L. G., Dear, B. F., Gandy, M., Fogliati, V., Fogliati, R., Karin, E., Nielssen, O., & Titov, N. (2019). Psychometric properties and clinical utility of brief measures of depression, anxiety, and general distress: The PHQ-2, GAD-2, and K-6. General Hospital Psychiatry, 56, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.11.003

Stein, R., & Horwitz, S. M., Storfer-Isser, A., Heneghan, A., Olson, L., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2008). Do pediatricians think they are responsible for identification and management of child mental health problems? Results of the AAP periodic survey. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 8(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2007.10.006

Thorne, S. (2008). Interpretive description. Left Coast Press.

Waid, J., Halpin, K., & Donaldson, R. (2021). Mental health service navigation: A scoping review of programmatic features and research evidence. Social Work in Mental Health, 19(1), 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2020.1870646

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201

Acknowledgements

We thank Heather Gordish-Dressman, PhD for her consultation on data analysis.

Funding

This paper was supported by a Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation Access to Care Fellowship (Dr. Godoy).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG was involved in all aspects of the study, including funding acquisition, study conceptualization, qualitative analysis, and drafting and revising the manuscript. RW led data collection and management, oversaw CPAP care coordination for the study, and contributed to qualitative analysis. LD and HF contributed to qualitative analysis and original draft preparation. SB completed quantitative analysis. GA oversaw family navigation group programming. AR, MGB, LSW, LSB, and ML contributed to funding acquisition and study conceptualization. All authors contributed to manuscript preparation, commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Leandra Godoy, Renee Williams, Lindsay Druskin, Hailey Fleece, Sujatha Bergen, Gail Avent, Adelaide Robb, Matthew G. Biel, Lawrence S. Wissow, Lee Savio Beers, and Melissa Long declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this manuscript to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Children’s National Hospital IRB.

Consent to Participate

Participants completed informed consent prior to participating.

Consent for Publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Godoy, L., Williams, R., Druskin, L. et al. Linking Primary Care to Community-Based Mental Health Resources via Family Navigation and Phone-Based Care Coordination. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 31, 471–492 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-023-09987-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-023-09987-9