Abstract

We conducted a review of empirically based prevention programs to identify prevalence and types of family support services within these programs. A total of 238 articles published between 1990 and 2011 that included a family support component were identified; 37 met criteria for inclusion. Following the Institute of Medicine’s typology, prevention programs were categorized as universal, selective, or indicated; programs containing more than one prevention level were characterized as multi-level. Family support types included those led by a mental health professional, led by a peer, or team-led. Among the 37 prevention programs reviewed, 27% (n = 10) were universal, 41% (n = 15) were selective, 16% (n = 6) were indicated, and 16% (n = 6) were multi-level. The predominant model of family support was professionally led (95%, n = 35). Two (n = 5%) provided team-led services. None were purely peer-led. In terms of content of family support services, all (100%, n = 37) provided instruction/skill build. Information and education was provided by 70% (n = 26), followed by emotional support (n = 11, 30%) and instrumental or concrete assistance (n = 11, 30%). Only 14% (n = 5) provided assistance with advocacy. The distribution of models and content of services in prevention studies differ from family support within treatment studies. As family support is likely to be an enduring component of the child and family mental health service continuum, comparative effectiveness studies are needed to inform future development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental health promotion via prevention or amelioration of risk factors has a robust research history in mental health (Barrera and Sandler 2006), particularly within the area of children’s mental health (Rishel 2007). Meta-analytic reviews have examined the impact of these programs across symptoms (e.g., depression, disruptive behaviors), settings (e.g., school-based programs), and risk factors (e.g., parental divorce; e.g., Beelmann 2006; Durlak and Wells 1997; Gillham et al. 2006; Horowitz and Garber 2006; Wilson et al. 2003). These reviews are notable for identifying a sizable number of empirically based prevention programs. The comprehensive Durlak and Wells (1997) review included 177 primary prevention programs (defined as health promotion and risk reduction interventions) and concluded that recipients of the interventions fared significantly better than youth in the control groups. Outcomes included symptom reduction and functioning with average effect sizes of 0.24–0.93. Furthermore, program benefits were maintained over time. A subsequent review (Durlak and Wells 1998) identified 130 indicated programs and found that behavioral and cognitive behavioral programs were effective at decreasing behavioral problems and improving functioning among youth; only seven programs had a negative effect (effect sizes ranged from −0.28 to 2.05).

Despite substantial research support for their efficacy, engaging families in these programs is challenging (Redmond et al. 2002; Spoth et al. 2007). Low recruitment and retention rates are reported in interventions that include parent involvement (see Spoth and Redmond 2000). To improve engagement, a growing number of prevention models are enlisting members of the target group’s community in recruitment efforts and delivery of the intervention (Prinz et al. 2001; Spoth et al. 2002, 2007). The use of lay community members within the field of prevention mirrors a movement in children’s mental health to train and employ parent peer support specialists (known by numerous names) to deliver family support services to parents or caregivers. The family support movement in children’s mental health has evolved since the late 1980s, with the newest models of service delivery involving direct peer-to-peer support provided by parents or caregivers of children who are raising or have raised a child with identified mental health needs to parents or caregivers (Hoagwood et al. 2010; Robbins et al. 2008). Because of their personal experience, parent peer support specialists often have a unique credibility with other parents and thus are able to engender trust and assist parents in becoming more actively engaged in their child’s services (Gyamfi et al. 2010; Hoagwood 2005; Koroloff et al. 1994; Osher et al. 2008; Robbins et al. 2008).

Family support as a service modality has been included in state mental health systems as one component of the overall service continuum since 1987, when the Child and Adolescent Service System Program (CASSP) was initiated (Katz-Levy 2011). The more recent addition to this model involves services provided by peer parents to parents/caregivers where the intent is to directly address parent/caregiver needs including clarifying and helping the parent to find their “voice”; reducing their sense of isolation, stress, or self-blame; providing education; teaching specific skills; and empowering and activating them, so that they can more effectively access and use mental health services.

In a review of family support services in children’s mental health treatments, Hoagwood et al. (2010) identified five types or content of services typically included in this service model: (a) instruction/skill development, including parenting strategies, anger management and stress reduction techniques, (b) information and education about mental health conditions; (c) emotional and affirmational support; (d) instrumental services (e.g., transportation, respite, childcare); and (e) advocacy, including provision of information about parental rights and resources, as well as skill building to help the parent advocate for their child’s services. See Table 1 for a fuller description of the five family support components.

This prior review also identified three primary models of family support: Those led by peers (i.e., parent peer support) accounted for 22% of the total sample (n = 11), while those delivered by mental health professionals were the largest category (n = 33, 67%). Those led by teams of peers and mental health professionals were the smallest category (n = 6, 12%). Similar content was found across types, but the emphasis varied. Overall, 86% (n = 41) of programs included instructional support/skill building, 74% (n = 37) included informational support, 46% (n = 23) advocacy, 44% (n = 22) emotional support, and 12% (n = 6) instrumental support.

Three key points emerged from this review. First, the peer-led model, unlike the professionally led or team-led models, included more content related to advocacy. This is not surprising, as this has been a core component of peer-led family services since CASSP. Second, programs led by mental health professionals were more likely to focus on skill building related to managing the child’s issues, while peer-led emphasized parent cognitions about their experiences and parent’s own needs. Third, we found that professionally led and team-led programs were more likely to have used experimental designs, most often with random assignment. Peer-led programs had a much thinner research base and lower-quality research methods.

Because of the rich research history on preventive interventions, we were unable to include these programs in our original review. Therefore, this paper provides a complementary review of family support within prevention programs. The purpose of this review is to identify prevalence and types of family support services within prevention programs, to compare the distribution to family support within treatment studies, and to examine the extent and content of peer support models in particular, as these represent an innovative and emerging model.

We address the following questions:

-

1.

What is the range and distribution of family support components within prevention programs for youth?

-

2.

How does the range and distribution in prevention compare to family support in treatment studies?

-

3.

How does the model of peer support (a subcategory of family support) in prevention compare to the peer support model in treatment studies?

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of prevention programs for children and adolescents that included family support for their parents/caregivers (hereafter called parents):

-

A computer search of the PsycINFO database from 1990 to present, using the stems prevent* and mental*. This search yielded 1,610 abstracts.

-

Website and Google searches.

-

Programs from the following widely recognized published reviews and compendiums: (1) The Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology’s special issue review of Evidence-Based Psychosocial Treatments for Children and Adolescents (2008); (2) Blueprints: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence Model and Promising Program (2011); (3) The Prevention Research Center for the Promotion of Human Development’s Prevention Research Center Ten-Year Report (1998–2008); (4) The Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA); Guide for selecting evidence-based practices for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior disorders (2008); (5) SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, NREPP (2011); (6) Durlak and Wells’s (1998) Evaluation of Indicated Prevention Intervention (Secondary Prevention) Mental Health Programs for Children and Adolescents; (7) Kutash et al. (2006) School-Based Mental Health: An Empirical Guide for Decision-Makers; (8) Meta-Analytic Review of Depression Prevention Programs for Children and Adolescents (Stice et al. 2009); (9) the 2008 Guide for Selecting and Adopting Evidence-based Practices for Children and Adolescents with Disruptive Behavior Disorders (Burns et al.); (10) Domintrovich and Greenberg’s (2000) study of implementation: Current findings from effective programs that prevent mental disorders in school-based children; and (11) Horowitz and Garber’s (2006) study: The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review.

-

The National Research Council and Institute of Medicine’s (2009) book, titled Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities.

-

Discussions with national experts from major national family advocacy organizations (e.g., NAMI, CHADD, National Federation).

To characterize programs, we followed the Institute of Medicine’s typology; (1) universal prevention programs, meaning prevention programs that target a total population; (2) selective, which are for specific groups based upon an identified risk factor, such as poverty or a traumatic event (e.g., the loss of a parent); or (3) indicated programs, which are designed for symptomatic youth before they have an established disorder (Cuijpers 2003; Kutash 2007; Mrazek and Haggerty 1994). Programs that had multiple types of prevention were characterized as multi-level.

Consistent with our earlier review (Hoagwood et al. 2010), we categorized family support as the provision of instruction (skills training), information (education), emotional support, concrete or instrumental support, and advocacy provided directly to parents within prevention programs. We also categorized programs as provided by professionals (e.g., school personnel, clinicians), those delivered by family members (peer-led), and those delivered by a family peer/professional team.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Prevention programs or interventions were included if they:

-

1.

provided instructional (skill building), educational, emotional, instrumental (concrete), or advocacy support for parents of children/adolescents who were targeted through universal prevention programs or were at risk for the onset of a psychiatric disorder (e.g., prevention of conduct disorder among youth with disruptive behavior problems) with the explicit goal of helping the parent.

-

2.

were published (as journal articles, chapters, or dissertations) between 1990 and September 2010 or are available via personal communication.

-

3.

had a formal curriculum or structure.

Prevention programs or interventions were excluded if they:

-

1.

provided treatments (i.e., targeted a specific syndrome or disorder).

-

2.

targeted youth with diagnosed mental disorders.

-

3.

primarily focused on preventing substance abuse, child abuse, school failure, or other non-mental health outcome.

-

4.

only provided information in the form of a flier or pamphlet. Programs required an active parent component to meet inclusion criteria.

-

5.

did not directly focus on social, emotional, or behavioral issues.

A word of clarification: Because of commonalities of psychosocial risk factors associated with various behavioral health outcomes, many programs exist that target a variety of risk factors that may also influence mental health outcomes. For example, programs with strong parent support components (e.g., National Head Start Association 2010; Strengthening Families Program 2010; Visiting Nurse Association of America 2010) focus their prevention on the promotion or prevention of outcomes such as education, school readiness, child abuse, or substance abuse. While these programs often demonstrate secondary positive behavioral health outcomes, the content does not specifically focus on emotional or behavioral issues. Home visiting programs, for example, typically provide one or more types of parental support, including parenting skills, linkages to resources and education about child development, and social support, although their main objectives are to prevent child abuse and neglect, encourage maternal self-sufficiency, reduce subsequent pregnancies, and promote academic readiness (Council on Community Pediatrics 2009). However, consistent with our stated exclusionary criteria, we limit our review to programs that have an explicit focus on reducing risk for the development of child mental health disorders and include an explicit focus on supporting the parent or caregiver.

Coding and Analysis

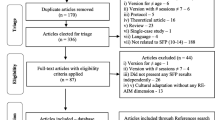

At least two of three authors (Cavaleri, Olin, and Kim) reviewed each of 238 published prevention programs that contained a parent/caregiver support component to determine their eligibility based upon the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. Thirty-seven programs were found to be eligible after this review. Next, the three authors systematically reviewed the prevention programs that met criteria in weekly meetings over a year. Programs were categorized as universal, selective, indicated, or multi-level as described by the Institute of Medicine’s typology (Durlak and Wells 1997). One author (MC) initially coded each of the programs and used the coding scheme as a basis for coding the programs based on the descriptions provided in the published articles and/or relevant sources. A second author (SO) reviewed each program to ensure inter-rater reliability. Any discrepancies were discussed among all of the authors until consensus was reached. The coding system was refined until no additional codes were needed.

Results

A total of 238 programs had an identified parent component, and of these, 37 (16%) met inclusion criteria (see Table 2 for a list of the included programs). The remaining 201 programs were excluded mainly for two reasons: (1) their primary focus was not on reducing the risk of mental health problems but rather other conditions (e.g., primary focus on child abuse, substance abuse, and academic readiness) or (2) they did not include parent/caregiver support beyond information in the form of a pamphlet or flier.

Program Characteristics

Of the 37 programs that met eligibility for inclusion, 10 (27%) were categorized as universal, 15 (41%) were selective, six (16%) were indicated, and six (16%) were multi-level. There were variations across program levels with respect to how youth was selected for inclusion. In line with population-based prevention efforts, universal prevention programs did not identify children by risk, but by setting (e.g., school, primary care, or daycare settings) and/or age-group (Center for Improvement of Child Caring Effective Black Parenting Program, Myers et al. 1992; Dare To Be You, Miller-Heyl et al. 1998; Family Based Partnership, Bradshaw et al. 2009; Universal Parenting Program, Hiscock et al. 2008). For example, the Early Home-Based Intervention, which aimed to reduce future behavior problems, recruited mothers who gave birth during three time periods at a healthcare setting and delivered the intervention when their infants were between 5 and 9 months of age (Cheng et al. 2007).

In contrast, the selective programs identified youth at risk for mental health difficulties based on parental/familial factors, including divorce, death, and psychiatric difficulties (n = 8, 53%), or aspects associated with economic disadvantage, such as low socioeconomic status, living in disadvantaged communities, and homelessness (n = 7, 47%). The Preventive Intervention Project (Clinician Based Cognitive Psychoeducational Intervention for Families, Beardslee et al. 2003), for instance, selected children between 8 and 15 years of age who were at risk based upon having one or more parents who were experiencing depression, while the Empowerment Zone program targeted children of families who were of low socioeconomic status or were living in homeless shelters (Nabors et al. 2001).

Most of the indicated programs (n = 4, 67%) targeted youth who was already exhibiting internalizing or externalizing problems (e.g., Coping Power Program, Lochman and Wells 2002; Early Risers, August et al. 2001): The remaining two programs selected youth based upon psychosocial stressors such as experiencing a trauma (Cognitive Behavioral intervention for Trauma in Schools, Morsette et al. 2009), or who were raised by a single parent (Parenting Through Change (DeGarmo and Forgatch 2005).

Not surprisingly, the criteria for entry into the multi-level prevention programs varied by prevention level. For example, Triple P (Sanders et al. 2000) contained a universal component consisting of information about parenting resources, which was available to the entire population of youth and families through various media (e.g., television and radio); a selective component (parenting advice and information) for children evidencing mild behavioral problems; and an indicated component, consisting of parenting strategies and, if needed, additional supports (i.e., coping skills) for parents who are experiencing stressors, such as their own emotional health issues.

Family Support Components

Across prevention levels, programs offered a similar number of supportive components to parents: Multi-level programs offered three family support components on average, followed by universal (2.5), indicated (2.3), and selective programs (2.2). Programs were also relatively similar across prevention levels with respect to the type of support delivered. All of the programs (n = 37, 100%) provided instructional skill development, and primarily parenting strategies (e.g., setting appropriate consequences for behaviors, monitoring, listening, and discipline), to prevent or decrease emotional and behavioral problems (e.g., Coping with Toddler Behavior, Niccols 2004; Coping Power Program, Lochman and Wells 2002). Twenty-six programs (70%) also provided information, both verbally and in the form of videotapes, booklets, and handouts, about child development and identified risks to the child’s mental health, including divorce, low socioeconomic status, and parental mental health problems (Children in the Middle, Brandon 2006; Dare to Be You, Miller-Heyl et al. 1998; Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers, Eddy et al. 2000).

Eleven programs (30%) provided instrumental support, such as food, transportation, and childcare, to reduce barriers to participation, build support, and encourage interaction among family members (e.g., Early Risers, August et al. 2001; Parenting Through Change, DeGarmo and Forgatch 2005). Although most programs, and particularly those which offered groups, were arguably conducive to shared exchanges of difficulties and affirmation from other parents, only 11 programs (30%) specified offering emotional support as a key component, either through discussions with program facilitators about personal issues or troubles or by building a supportive network with other parents (e.g., Early Alliance, Dumas et al. 1999; Protecting Families Program, Boyd et al. 2006). The fifth and least-represented form of parent support was advocacy, which was provided by five programs (14%), and was primarily in reference to advocating within the educational system (e.g., Gorman-Smith et al. 2002).

As a whole, the number and type of family support offered to parents were similar irrespective of whether the child was identified as being at risk due to child difficulties (e.g., based on teacher or parent report about behavior, such as in the Adolescent Transition Program, Dishion and Kavanagh 2000), or parental factors (e.g., divorce, parental mental health, e.g., Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008; New Beginnings Program, Wolchik et al. 2009). Programs that focused on externalizing difficulties (e.g., Fast Track, Nix et al. 2005; Triple P Positive Parenting Program, Sanders et al. 2000) did not offer unique or more support components than programs that targeted internalizing symptoms (e.g., Child Anxiety Prevention Study, Ginsburg 2009) or externalizing and internalizing difficulties (e.g., Home-Based Intervention, Aronen and Kurkela 1996).

Although programs across prevention levels were mainly concordant, three differences were apparent. First, none of the universal prevention programs provided advocacy as a form of support; of the five programs that did offer this type of family support, two were selective (Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group, Tolan and McKay 1996; SAFE Children, Tolan et al. 2004), one program was indicated (Early Risers, August et al. 2001), and the remaining two were multi-level (Early Alliance, Dumas et al. 1999; Fast Track, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2007).

Second, among the indicated programs, emotional support was offered most frequently after instructional support (n = 3, 50%), while the other prevention levels provided informational support most frequently after instructional support (n = 9, 90% among the universal programs; n = 10, 67% among the selective programs; and n = 5, 83% among the multi-level programs). Third, the multi-level programs typically provided information support for the universal component, while the other supportive components were provided in the selective/indicated programs (e.g., Raising Healthy Children, Catalano et al. 2003; Triple P, Sanders et al. 2000). For example, Triple P’s universal component offered information about parenting resources, the selective component offered instructional support in the form of parenting skills, and the indicated part offered both parenting skills and additional instructional support, including teaching parents coping skills (relaxation techniques, self-statements) and communication and listing skills to enhance parents’ relationship with each other (Sanders et al.). See Table 3 for a comparison of the types and number of family support components by prevention level.

Outcomes and Impact

Another similarity across prevention levels was a primary focus on reducing child symptoms, although there was some variability with respect to symptom type. The universal and multi-level programs mostly focused on reductions in externalizing behaviors (n = 7, 70% of universal programs; n = 4, 80% of the five multi-level programs that studied child outcomes). Among the 13 selective programs that studied child outcomes, six focused on reducing externalizing behaviors (Children in the Middle, Brandon 2006; Empowerment Zone, Nabors et al. 2001; Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group [MACS], Tolan and McKay 1996; Parent Management Training-Oregon [PMT-O], Patterson et al. 1982; Parent Training, Garvey et al. 2006; SAFEChildren, Gorman-Smith et al. 2002), and seven focused on internalizing behaviors either alone (Child Anxiety Prevention Study, Ginsburg 2004; Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008) or in conjunction with externalizing behaviors (e.g., Children of Divorce Intervention Program, Wolchik et al. 1993; Family Bereavement Program, Lochman et al. 2009; Montreal Longitudinal Study/Preventive Treatment Program, Pagani et al. 1999; New Beginnings Program, Hipke et al. 2002; Preventive Intervention Project [Clinician Based Cognitive Psychoeducational Intervention for Families], Beardslee et al. 2002). An equal number of indicated programs focused on externalizing behaviors (e.g., Coping Power, Lochman and Wells 2002; Early Risers, August et al. 2001; Parenting Through Change, DeGarmo and Forgatch 2005) and reducing internalizing difficulties, such as depression and PTSD (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Interventions for Trauma in Schools [CBITS], Morsette et al. 2009; Penn Resiliency Program, Roberts et al. 2004; Queensland Early Intervention and Prevention Anxiety Project [QEIPEP], Dadds et al. 1997).

The impact of programs was mixed, particularly among the universal and selective interventions: For instance, 6 of the 10 universal programs (60%) showed favorable results in comparison with control and comparison groups at posttest and over time. For the four remaining programs, the intervention did not appear to be more beneficial than control or had no impact. Among the selective programs, several studies showed significant improvements in behavioral problems at posttest and/or follow-up comparative to another intervention condition (e.g., a self-study group in Family Bereavement Program, Sandler et al. 2003, or control group, e.g., Beardslee et al. 2003). Several studies, however, either did not find significant differences between groups or found a positive impact upon only some outcomes (e.g., SAFE Children was associated with improvements in academic performance in comparison with the control group, but not child behavior, Tolan et al. 2004).

Studies of the indicated and multi-level programs were more consistently positive. For all but one indicated program, child outcomes were favorable at posttest and/or follow-up. Findings of the remaining program (Penn Resiliency Program, Gillham et al. 2006; Roberts et al. 2004) were mixed. In one study, youth evidenced improvements in depression at the 2-year follow-up point in comparison with the control group, yet not at 3-year follow-up (Roberts et al. 2004). In a second study, children in two schools who received PRP evidenced significant reductions in depressive symptoms over a comparison treatment and a control group, but not in a third school (Gillham et al. 2007).

Parent outcomes beyond program satisfaction were studied secondarily across prevention levels, and results were generally favorable. Among the universal programs, six of the seven programs that focused on parent outcomes beyond treatment satisfaction examined parenting practices (e.g., use of positive parenting strategies, appropriate discipline; e.g., DTBY, Miller-Heyl et al. 1998; EBPP, Myers et al. 1992; FSP, Ialongo et al. 2001; Bradshaw et al. 2009; LIFT, Reid et al. 1999; UPP, Hiscock et al. 2008) or aspects of the parent/child relationship (e.g., parental rejection, EBPP; dysfunctional interactions, CWTB, Niccols 2004). Five of the six programs (83%) were associated with improvements in one or both of these areas, while results of the sixth program, FSP, were mixed: The intervention did not appear to significantly impact parental monitoring or discipline, but was associated with a greater number of reinforcing activities and decreased rejection toward their child (Bradshaw et al. 2009; Ialongo et al. 2001).

Almost half (n = 3, 43%) of universal programs that focused on parenting outcomes also examined the parent’s emotional health, including self-esteem, parenting self-efficacy, depression, anxiety, and stress. Results were varied; parents who participated in DTBY (Miller-Heyl et al. 1998), for example, evidenced greater increases in self-esteem and parenting self-efficacy in comparison with the control group, and these gains were maintained at 2-year follow-up. Likewise, parents who participated in RAP-F (Shochet et al. 2001) reported improvements in self-efficacy. However, mothers who received the Universal Prevention Program (Hiscock et al. 2008) did not evidence any difference in depression, anxiety, or stress in comparison with the control group either at 18 or 24 months following baseline (Hiscock et al. 2008).

Eleven selective programs (73%) investigated parent outcomes beyond satisfaction with services. Most found a beneficial impact of the prevention intervention on improved parenting and knowledge about parenting strategies (n = 6, 55%; CODIP, Wolchik et al. 1993; Dads for Life, Cookston et al. 2006; Empowerment Zone, Nabors et al. 2001; Family Bereavement Program, Sandler et al. 2003; Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008; New Beginnings Program, Wolchik et al. 2002; PMT-O, Patterson et al. 1982), the relationship between parent and child (n = 2, 18%; CODIP, Wolchik et al. 1993), decreased interpersonal conflict (n = 1, 6%; Dads for Life, Cookston et al. 2006), and increased knowledge and communication about their mental illness to their child (n = 1, 6%; Preventive Intervention Project [Clinician Based Cognitive Psychoeducational Intervention for Families], Beardslee et al. 2002).

Three of the eleven studies that focused on parent outcomes found mixed results, however (e.g., Children in the Middle, Kramer et al. 1998; SAMHSA 2006; Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008; SAFE Children, Gorman-Smith et al. 2002). CIM, for example, was associated with improved communication skills, but neither CIM nor the control group was associated with reduced parent conflict regarding child issues (Kramer et al. 1998). In a second study (Brandon 2006), CIM was associated with increased partner conflict, although parents in the intervention group also evidenced reductions in putting their child in between parents’ conflict. The third study (Gillard and Seymour 2005) found increased knowledge about how separation impacts children and decreased conflict among parents at 4-month follow-up.

Four selective programs identified the child as at risk based upon parental mental health (CAPS, Riley et al. 2008; Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008; Preventive Intervention Project, Beardslee et al. 2002, 2003, 2007; Protecting Families Program, Boyd et al. 2006), but only one studied the parent’s emotional health as a direct outcome (Keeping Families Strong, Riley et al. 2008). The other three programs that examined parent’s emotional health targeted children whose caregiver or parent died within the past 2½ years (Family Bereavement Program, Sandler et al. 2003, 2010), or youth who was exhibiting problem behaviors (Parent Management Training-Oregon, DeGarmo et al. 2009; Parent Training, Garvey et al. 2006). Overall, results suggested that these programs were effective at reducing depression, anxiety, and/or stress. Mothers who participated in the PMT-O group, for example, evidenced significant decreases in depressive symptoms in comparison with the control group, and these effects continued over time (Patterson et al. 2004). Further, engagement in Parent Training (Garvey et al. 2006) was associated with decreased depressive symptoms.

Fewer indicated (n = 3, 50%) and multi-level (n = 2, 33%) programs studied parent outcomes than the universal and selective categories. Results were generally positive among these programs, with results suggesting increases in positive parenting and appropriate disciplinary methods (Coping Power Program, Lochman and Wells 2002; Parenting Through Change, Forgatch and DeGarmo 1999; Triple P Positive Parenting Program, Sanders et al. 2000) and decreased feeling of distress (Incredible Years, Webster-Stratton et al. 2004).

Beyond the child and parent, several programs, and particularly the universal and selective programs, studied family-level factors including family relationships (EBPP) and family functioning (RAP-F). Here too, results were mixed; results of EBPP (Myers et al. 1992) showed significant improvement in family relationships from pre- to posttest, although findings of RAP-F did not find an impact of the intervention upon family functioning, based upon adolescent report. Result from studies of selective programs that explored domestic violence (CIM, Kramer et al. 1998; SAMHSA 2006) and family functioning (Beardslee et al. 2007) showed improvements in outcomes, but no discernible benefit of the intervention group over control. Alternately, families who received KFS (Riley et al. 2008; Wilhelm 2006) evidenced increased family involvement around mealtime and chores in comparison with the control group.

Parent Peer Support

Parent peer support models were rare. Ninety-five percent (n = 35) of the programs in our review were delivered by mental health professionals, including social workers, psychologists, counselors, master’s level students-in-training (e.g., Parent Management Training, Oregon, DeGarmo and Forgatch 2005; RAP-F, Shochet et al. 2001), teachers (e.g., FRIENDS (Lowry-Webster et al. 2001), and nurses (Home-Based Intervention, Aronen and Kurkela 1996). Only two programs (5%) included a parent peer in delivering the service: Early Risers (August et al. 2001, 2003, 2006) and Fast Track (Bierman et al. 2006; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group 2007). In both Early Risers and Fast Track, the parent peer co-led the support with a mental health professional. Parent peers led none of the programs alone.

The roles of peers in the two co-led programs varied: Peers who co-led the Early Risers program (August et al. 2001), an indicated prevention program for children with behavioral problems, worked with school advocates and were primarily responsible for recruitment, referral, and instrumental support. The model was derived from The Incredible Years (e.g., Webster-Stratton et al. 2004). Peers in the Fast Track program, a multi-level program also for youth exhibiting behavioral problems, worked directly with the youth by providing social skills support to them, while teachers and former teachers (educational coordinators) delivered a classroom component, and professional mental health providers (e.g., social workers, counselors) delivered the parent group (Nix et al. 2005).

There were two notable variations between co-led and professionally led programs. First, both co-led programs offered advocacy support, a relative rarity among the professionally led programs (only three or 9% of the 35 professionally led programs offered advocacy comparatively). And second, the co-led programs were the only prevention programs that offered all five family support components. For instance, Fast Track provided parenting, communication, and problem-solving skills; emotional support for high-risk parents during home visits; transportation, food, and childcare for siblings; assisted parents in advocating for their child; and information about the child’s program components (a universal classroom component, and tutoring, a social skills group and a mentoring program for high-risk youth; Nix et al. 2005). The remaining 35 prevention programs offered between one and four family support components.

Discussion

Because family support services are a growing component of the continuum of mental health services, and because anticipated continuation of workforce shortages (Annapolis Coalition, 2007) is likely to lead to expansion of this service, understanding its typologies, core components, and its distribution within empirically based prevention programs can assist policy-makers, service providers, and researchers in refining conceptualization of this service model.

Comparisons between this review and our earlier study of family support in treatment programs for children with recognized mental health problems must be done cautiously given differences in inclusion criteria. Further, while program outcomes are important, our main aim was to describe family support components in prevention efforts; to do so, we reviewed programs with family support components, regardless of their impact. Additional limitations of the current review, such as exclusion of programs that were secondarily focused on behavioral health outcomes, a shortage of prevention models led by parent peers, and a lack of specificity regarding effect sizes, dosage, and intensity of family support, warrant mention when interpreting the results of this undertaking and any comparisons with our earlier review.

However, as described below, some tentative conclusions can be drawn.

Key Findings: Types of Family Support

Consistent with our earlier review of treatment programs, instruction/skill building was the most commonly provided supportive component among prevention programs. The primary form of instructional support was parenting skills, irrespective of prevention category or risk factor. To a lesser degree, programs offered strategies to manage the parent’s distress or symptoms. The rationale for addressing the parent’s emotional health was similar to what we found among the professionally led treatment programs to increase the parents’ capacity to support the child (e.g., helping the parent manage their own coping so that they can model and support the child’s intervention). Prominent components of peer-led treatment interventions, including self-care, assisting the parent in coping with stress, and skill training targeted at the parent, not at behavior management (e.g., NAMI Basics; Visions for Tomorrow 2007), were notably absent from the prevention programs in this review.

Family support focused on providing information, and education was the second most common type of content. Prevention programs provided information about normal child and adolescent development (e.g., Universal Parenting Program, Hiscock et al. 2008; Resourceful Adolescent Program-Family, Harnett and Dadds 2004) and risks to the child’s mental health, such as parental conflict (Children in the Middle, Brandon 2006) and substance use (Center for the Improvement of Child Caring Effective Black Parenting Program, Myers et al. 1992). Not surprisingly, a focus of information provision in the treatment interventions emphasized information about mental disorders, their symptoms, course, and treatments (e.g., Cognitive Behavioral Family Therapy, Barrett et al. 2004; Cognitive Behavioral Therapy + Parent Anxiety Management, Cobham et al. 1998; Trauma Focused-Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cohen et al. 2004).

Few prevention programs provided advocacy support (n = 5, 14%). Its limited representativeness here is not surprising, however, especially among the universal programs, in which an identified service need may not exist. In contrast, in treatment programs targeting children with identified mental health needs, their families are at increased likelihood of interacting with other service systems, such as schools and the legal system. Consequently, support services for these families are likely to include a focus on advocacy.

Key Findings: Parent Peer Support Models

This is an underdeveloped area. It comprised 22% in the treatment literature; pure parent-led models were absent in the prevention literature, and only 5% of programs included team-led models. There are several explanations for this. Historically, paraprofessionals have aided in recruitment and outreach within community-based prevention programs, not service delivery (Kegeles et al. 1996; Woods et al. 1998). Thus, to a certain extent, the paradigm of prevention programs already includes community members as core partners. And in fact, some of these community partners may in fact have been parent peers, but not necessarily identified as such.

Secondly, family run organizations such as the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) and the National Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health, which are the major forces behind advancing peer-delivered models, have traditionally concentrated their efforts on providing support to families of children with serious mental disorders, rather than children at risk. Thus, national advocacy for family support has not traditionally focused on prevention. However, workforce shortages (SAMHSA 2007) in systems where prevention programs exist (schools, pediatric settings) coupled with an emerging literature showing how peers bring unique strengths to their work with families (e.g., credibility, trustworthiness; Hoagwood et al. 2010), suggests that there may be an increased demand for peer-delivered services in the future.

Implications and Future Research

As noted above, comparative studies of the relative effectiveness of different models of family support are needed. There are likely to be advantages and disadvantages to each of the models. Although employing parent peers runs the same risk as employing community members to deliver interventions and may raise the risk of ethical and boundary issues (e.g., threats to confidentiality, overstepping their boundaries, and over-identification with participants; Jain 2010), there may be advantages that future research can examine. These include greater ease in building rapport (Prinz et al. 2001), utilizing recruitment strategies that are contextually appropriate, and increasing the likelihood that preventive efforts will be sustained by tapping into the natural resources of the community (Spoth et al. 2007).

The concerns about risks involved in peer-delivered services are being addressed via the development of specific competency-based trainings for parent peers (e.g., Olin et al. 2009; University of Connecticut’s Family Development Credential Program 2010). National certification standards are currently being developed (Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health 2010), and some states are also doing so (e.g., New York, Illinois). Increasingly, the role of parent peers as an emerging workforce to deliver family support services is becoming recognized through billable services in several states (e.g., New York, Maryland, South Carolina). Data on the unique impact of family support in general, and specific models, such as team-led and peer-led services, on family and child outcomes are still limited. Both efficacy and effectiveness studies are greatly needed. Given the unfunded mandate of many prevention efforts, use of indigenous resources—such as parent peers—is likely to be an important factor in sustaining prevention programs and reducing the burden of mental health costs.

References

Annapolis Coalition on Behavioral Health Workforce. (2007). Action plan on behavioral health workforce development (Publication No. 280-02-0302). Washington, DC: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Aronen, E. T., & Arajarvi, T. (2000). Effects of early intervention on psychiatric symptoms of youth adults in low-risk and high-risk families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(2), 223–232.

Aronen, E. T., & Kurkela, S. A. (1996). Long-term effects of an early home-based intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35(12), 1665–1672.

August, G. J., Bloomquist, M. L., Lee, S. S., Realmuto, G. M., & Hektner, J. M. (2006). Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The Early Risers’ advanced-stage effectiveness trial. Prevention Science, 7(2), 151–165.

August, G. J., Egan, E. A., Realmuto, G. M., & Hektner, J. M. (2003). Four years of the Early Risers early-age-targeted preventive intervention: Effects on aggressive children’s peer relations. Behavioral Therapy, 34, 453–470.

August, G. J., Realmuto, G. M., Hektner, J. M., & Bloomquist, M. L. (2001). An integrated components preventive intervention for aggressive elementary school children: The Early Risers Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 614–626.

Barrera, M., & Sandler, I. N. (2006). Prevention: A report of progress and momentum into the future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(3), 221–226.

Barrett, P. M., Healy-Farrell, L. J., & March, J. S. (2004). Cognitive behavioural family based treatment for childhood OCD: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 46–63.

Beardslee, W. R., Gladstone, T. R. G., Wright, E. J., & Cooper, A. B. (2003). A family-based approach to the prevention of depressive symptoms in children at risk: Evidence of parental and child change. Pediatrics, 112, 119–131.

Beardslee, W. R., Hoke, L., Wheelock, I., Rothberg, P. C., van de Velde, P., & Swatling, S. (2002). Initial findings on preventive intervention for families with parental affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 149, 1335–1340.

Beardslee, W. R., Wright, E. J., Gladstone, T. R. G., & Forbes, P. (2007). Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 703–713.

Beelmann, A. (2006). Review of systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. European Psychologist, 11(3), 244–245.

Bierman, K. L., Nix, R. L., Maples, J. J., Murphy, S. A., & the Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2006). Examining clinical judgment in an adaptive intervention design: The Fast Track Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 468–481.

Blueprints: Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence Model and Promising Program. (2011). Downloaded August 1, 2011 from www.colorado.edu/cspv/blueprints/.

Boyd, R. C., Diamond, G. S., & Bourjolly, J. N. (2006). Developing a family-based depression prevention program in urban community mental health clinics: A qualitative investigation. Family Process, 45, 187–203.

Bradshaw, C. P., Zmuda, J. H., Kellam, S. G., & Ialongo, N. S. (2009). Longitudinal impact of two universal preventive interventions in first grade on educational outcomes in high school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(4), 926–937.

Brandon, D. J. (2006). Can four hours make a difference? Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 45(1–2), 171–185.

Catalano, R. F., Mazza, J. J., Harachi, T. W., Abbott, R. D., Haggerty, K. P., & Fleming, C. B. (2003). Raising healthy children through enhancing social development in elementary school: Results after 1.5 Years. Journal of School Psychology, 41, 143–164.

Cheng, S., Kondo, N., Aoki, Y., Kitamura, Y., Takeda, Y., & Yamagata, Z. (2007). The effectiveness of early intervention and the factors related to child behavioral problems at age 2: A randomized controlled trial. Early Human Development, 83, 683–691.

Cobham, V. E., Dadds, M. R., & Spence, S. H. (1998). The role of parental anxiety in the treatment of childhood anxiety. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology, 66, 893–905.

Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. (2004). A multisite randomized controlled trial for sexually abused children with PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 393–402.

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2007). Fast Track randomized controlled trial to prevent externalizing psychiatric disorders: Findings from grades 3 to 9. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(10), 1250–1262.

Cookston, J. T., Braver, S. L., Sandler, I., & Genalo, M. T. (2006). Prospects for expanded parent education services for divorcing families with children. Family Court Review, 40(2), 189–202.

Council on Community Pediatrics. (2009). The role of preschool home-visiting programs in improving children’s developmental and health outcomes. Pediatrics, 123, 598–603.

Cuijpers, P. (2003). Examining the effects of prevention programs on the incidence of new cases of mental disorders: The lack of statistical power. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1385–1391.

Dadds, M. R., Holland, D. E., Laurens, K. R., Mullins, M., Barrett, P. M., & Spence, S. H. (1999). Early intervention and prevention of anxiety disorders in children: Results at 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 145–150.

Dadds, M. R., Spence, S. H., Holland, D., Barrett, P. M., & Laurens, K. (1997). Early intervention and prevention of anxiety disorders: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 627–635.

DeGarmo, D. S., Eddy, J. M., Reid, J. B., & Feetrow, R. A. (2009). Evaluating mediators of the impact of the Linking the Interests of Families and Teachers (LIFT) multimodal preventive intervention on substance use initiation and growth across adolescence. Prevention Science, 10, 208–220.

DeGarmo, D. S., & Forgatch, M. S. (2005). Early development of delinquency within divorced families: Evaluating a randomized preventive intervention trial. Developmental Science, 8(3), 229–239.

Dishion, T. J., & Kavanagh, K. (2000). A multilevel approach to family-centered prevention in schools: Process and outcome. Addictive Behaviors, 25(6), 899–911.

Domintrovich, C. E., & Greenberg, M. T. (2000). The study of implementation: Current findings from effective programs that prevent mental disorders in school-aged children. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 11(2), 193–221.

Dumas, J. E., Lynch, A. M., Laughlin, J. E., Smith, E. P., & Prinz, R. J. (2001). Promoting intervention fidelity: Conceptual issues, methods, and preliminary results form the Early Alliance prevention trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20, 38–47.

Dumas, J. E., Prinz, R. J., Smith, E. P., & Laughlin, J. (1999). The Early Alliance prevention trial: An integrated set of interventions to promote competence and reduce risk for conduct disorder, substance abuse, and school failure. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 2(1), 37–53.

Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1997). Primary prevention mental health programs for children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 115–152.

Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1998). Evaluation of indicated preventive intervention (secondary prevention) mental health programs for children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26(5), 775–802.

Eddy, J. M., Reid, J. B., & Fetrow, R. A. (2000). An elementary school-based prevention program targeting modifiable antecedents of youth delinquency and violence: Linking the interests of families and teachers (LIFT). Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(3), 165–176.

Federation of Families for Children’s Mental Health. (2010). Certification. Accessed November 11, 2010 from http://www.ffcmh.org/what-we-do/certification-2/overview/.

Forgatch, M. S., & DeGarmo, D. S. (1999). Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 711–724.

Garvey, C., Julion, W., Fogg, L., Kratovil, A., & Gross, D. (2006). Measuring participation in a prevention trial with parents of young children. Research in Nursing and Health, 29, 212–222.

Gillard, L., & Seymour, F. (2005). Children in the middle: A parent education programme for separated parents. Auckland, Australia: Department of Psychology, University of Auckland.

Gillham, J. E., Hamilton, J., Freres, D. R., Patton, K., & Gallop, R. (2006). Preventing depression among early adolescents in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled study of the Penn Resiliency Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(2), 203–219.

Gillham, J. E., Reivich, K. J., Freres, D. R., Chaplin, T. M., Shatte, A. J., Samuels, B., et al. (2007). School-based prevention of depressive symptoms: A randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and specificity of the Penn Resiliency Program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 9–19.

Ginsburg, G. S. (2004). Anxiety prevention programs for youth: Practical and theoretical considerations. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(4), 430.

Ginsburg, G. S. (2009). The Child Anxiety Prevention Study: Intervention model and primary outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 580–587.

Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., Henry, D. B., Leventhal, A., Schoeny, M., Lutovsky, K., et al. (2002). Predictors of participation in a family-focused preventive intervention for substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(4S), S55–S64.

Gyamfi, P., Walrath, C., Burns, B. J., Stephens, R. L., Geng, Y., & Stambaugh, L. (2010). Family education and support services in systems of care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(1), 14–26.

Haggerty, K. P., Fleming, C. B., Catalano, R. F., Harachi, T. W., & Abbott, R. D. (2006). Raising Healthy Children: Examining the impact of promoting healthy driving behavior within a social development intervention. Prevention Science, 7, 257–267.

Harnett, P. H., & Dadds, M. R. (2004). Training school personnel to implement a universal school-based prevention of depression program under real-world conditions. Journal of School Psychology, 42, 343–357.

Hipke, K. N., Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., & Braver, S. L. (2002). Predictors of children’s intervention-induced resilience in a parenting program for divorced mothers. Family Relations, 51(2), 121–129.

Hiscock, H., Bayer, J. K., Price, A., Ukoumunne, O. C., Rogers, S., & Wake, M. (2008). Universal parenting programme to prevent early childhood behavioural problems: Cluster randomised trial. British Medical Journal, 336(7639), 318–321.

Hoagwood, K. E. (2005). Family-based services in children’s mental health: A research review and synthesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(7), 670–713.

Hoagwood, K. E., Cavaleri, M., Olin, S. S., Burns, B. J., Gruttadaro, J. D., & Hughes, R. (2010). Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13, 1–45.

Horowitz, J. L., & Garber, J. (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 401–415.

Ialongo, N., Poduska, J., Werthamer, L., & Kellam, S. (2001). The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 146–160.

Jain, S. (2010). The role of paraprofessionals in providing treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in low-resource communities. Journal of the American Medical Association, 304(5), 571–572.

Katz-Levy, J. (2011). New roles for families in building systems of care: A CASSP perspective. Downloaded August 1, 2011 from http://www.familyreunion.org/FR_07/katzleavy/roles.html.

Kegeles, S. M., Hays, R. B., & Coates, T. J. (1996). The Mpowerment Project: A community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay men. American Journal of Public Health, 86(8), 1129–1136.

Klimes-Dougan, B., August, G. J., Lee, C.-Y. S., Realmuto, G. M., Bloomquist, M. L., Horowitz, J. J., et al. (2009). Practitioner and site characteristics that relate to fidelity of implementation: The Early Risers prevention program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 467–475.

Koroloff, N. M., Elliott, D. J., Koren, P. E., & Friesen, B. J. (1994). Connecting low-income families to mental health services: The role of the family associate. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2(4), 240–246.

Kramer, K. M., Arbuthnot, J., Gordon, D. A., Roussis, N., & Hoza, J. (1998). Effects of skill-based vs. information-based divorce education programs on domestic violence and parental communication. Family and Conciliation Courts Review, 36(1), 9–31.

Kutash, K. (2007). Understanding school-based mental health services for students who are disruptive and aggressive: What works for whom? In Proceedings of persistently safe schools: The 2007 national conference on safe schools and community. Retrieved March 12, 2009, from: http://www.hamfish.org/.

Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., & Lynn, N. (2006). School-based mental health: An empirical guide for decision-makers. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Dept. of Child and Family Studies, Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health.

Lee, C.-Y. S., August, G. J., Realmuto, G. M., Horowitz, J. L., Bloomquist, M. L., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2008). Fidelity at a distance: Assessing implementation fidelity of the Early Risers prevention program in a going-to-scale intervention trial. Prevention Science, 9, 215–229.

Lochman, J. E., Boxmeyer, C., Powell, N., Qu, L., Wells, K., & Windle, M. (2009). Dissemination of the Coping Power Program: Importance of intensity of counselor training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 397–409.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2002). Contextual social-cognitive mediators and child outcome: A test of the theoretical model in the Coping Power Program. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 971–993.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2003). Effectiveness study of Coping Power and classroom intervention with aggressive children: Outcomes at a one-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy, 34, 493–515.

Lochman, J. E., & Wells, K. C. (2004). The Coping Power Program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Outcome effects at the one-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 571–578.

Lowry-Webster, H. M., Barrett, P. M., & Dadds, M. R. (2001). A universal prevention trial of anxiety and depressive symptomatology in childhood: Preliminary data from an Australian study. Behaviour Change, 18(1), 36–50.

Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group. (2002). A cognitive/ecological approach to preventing aggression in economically-disadvantaged urban settings: Preliminary outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 179–194.

Metropolitan Area Child Study Research Group. (2007). Changing the way children “think” about aggression: Social-cognitive effects of a preventive intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 160–167.

Miller-Heyl, J., MacPhee, D., & Fritz, J. J. (1998). DARE to be you: A family-support, early prevention program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 18(3), 257–285.

Morsette, A., Swaney, G., Stolle, D., Schuldberg, D., van den Pol, R., & Young, M. (2009). Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS): School-based treatment on a rural American Indian reservation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40, 169–178.

Mrazek, P. B., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Myers, H. F., Alvy, K. T., Arrington, A., Richardson, M. A., Marigna, M., Huff, R., et al. (1992). The impact of a parent training program on inner-city African-American families. Journal of Community Psychology, 20, 132–147.

Nabors, L., Proescher, E., & DeSilva, M. (2001). School-based mental health prevention activities for homeless and at-risk youth. Child & Youth Care Forum, 30(1), 3–18.

Nabors, L. A., Weist, M. A., Shugarman, R., Woeste, M. J., Mullet, E., & Rosner, L. (2004). Assessment, prevention, and intervention activities in a school-based program for children experiencing homelessness. Behavior Modification, 28, 565–578.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). (2007). NAMI Basics; vision for Tomorrow. Accessed January 1, 2010 from www.NAMI.org.

National Head Start Association. (2010). Accessed January 1, 2010 from http://www.nhsa.org/.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. In M. E. O’Connell, T. Boat, & K. E. Warner (Eds.), Committee on the prevention of mental disorders and substance abuse among children, youth, and young adults: Research advances and promising interventions. Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press.

Ngo, V., Langley, A., Kataoka, S. H., Nadeem, E., Escudero, P., & Stein, B. D. (2008). Providing evidence-based practice to ethnically diverse youths: Examples from the cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS) program. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 858–862.

Niccols, A. (2004). An ounce of prevention: COPEing with Toddler Behavior. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(12), 869.

Niccols, A. (2009). Immediate and short-term outcomes of ‘COPEing with Toddler Behaviour’ parent group. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 617–626.

Nix, R. L., Pinderhughes, E. E., Bierman, K. L., Maples, J. J., & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2005). Decoupling the relation between risk factors for conduct problems and the receipt of intervention services: Participation across multiple components of a prevention program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3–4), 307–325.

Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Rodriguez, J., Ramos, B., Burton, G., Penn, M., et al. (2009). The application of behavior change theory to family-based services: Improving parent empowerment in children’s mental health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 462–470.

Orrell-Valente, J. K., Pinderhughes, E. E., Valente, E., Laird, R. D., & The Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (1999). If it’s offered, will they come? Influences on parents’ participation in a community-based conduct problems prevention program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(6), 753–783.

Osher, T., Penn, M., & Spencer, S. A. (2008). Partnerships with families for family-driven systems of care. In B. A. Stroul & G. M. Blau (Eds.), The system of care handbook: Transforming mental health services for children, youth, and families (pp. 249–274). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Pagani, L., Boulerice, B., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (1999). Effects of poverty on academic failure and delinquency in boys: A change and process model approach. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40(8), 1209–1219.

Patterson, G. R., Chamberlain, P., & Reid, J. B. (1982). A comparative evaluation of a parent-training program. Behavior Therapy, 13, 638–650.

Patterson, G. R., DeGarmo, D., & Forgatch, M. S. (2004). Systematic changes in families following prevention trials. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(6), 621–633.

Prinz, R. J., Dumas, J. E., Smith, E. P., & Laughlin, J. E. (2000). The Early Alliance prevention trial: A dual design to test reduction of risk for conduct problems, substance abuse, and school failure in childhood. Controlled Clinical Trials, 21, 286–302.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Luttzker, J. R. (2009a). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science, 10, 1–12.

Prinz, R. J., Sanders, M. R., Shapiro, C. J., Whitaker, D. J., & Lutzker, J. R. (2009b). Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P System Population Trial. Preventive Science, 10, 1–12.

Prinz, R. J., Smith, E. P., Dumas, J. E., Laughlin, J. E., White, D. W., & Barrón, R. (2001). Recruitment and retention of participants in prevention trials involving family-based interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 20, 31–37.

Redmond, C., Spoth, R., & Trudeau, L. (2002). Family- and community-level predictors of parent support seeking. Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 153–171.

Reid, J. B., Eddy, J. M., Fetrow, R. A., & Stoolmiller, M. (1999). Description and immediate impacts of a preventive intervention for conduct problems. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27(4), 483–517.

Riley, A. W., Valdez, C. R., Barrueco, S., Mills, C., Beardslee, W., Sandler, I., et al. (2008). Development of a family-based program to reduce risk and promote resilience among families affected by maternal depression: Theoretical basis and program description. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 12–19.

Rishel, C. A. (2007). Evidence-based prevention practice in mental health: What is it and how do we get there? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 153–164.

Robbins, V., Johnston, J., Barnett, H., Hobstetter, W., Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., et al. (2008). Parent to parent: A synthesis of the emerging literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, The Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Department of Child & Family Studies.

Roberts, C., Kane, R., Bishop, B., Matthews, H., & Thomson, H. (2004). The prevention of depressive symptoms in rural school children: A follow-up study. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 6(3), 4–16.

Sanders, M. R., Bor, W., & Morawska, A. (2007). Maintenance of treatment gains: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self directed Triple P—Positive Parenting Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 983–998.

Sanders, M. R., Montgomery, D. T., & Brechman-Toussaint, M. L. (2000). The mass media and the prevention of child behavior problems: The evaluation of a television series to promote positive outcomes for parents and their children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(7), 939–948.

Sandler, I. N., Ayers, T. S., Wolchik, S. A., Tein, J., Kwok, O., Haine, R. A., et al. (2003). The Family Bereavement Program: Efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(3), 587–600.

Sandler, I. N., Ma, Y., Tein, J. Y., Ayers, T. S., Wolchik, S., Kennedy, C., et al. (2010). Long-term effects of the Family Bereavement Program on multiple indicators of grief in parentally bereaved children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 131–143.

Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Holland, D., Whitefield, K., Harnett, P. H., & Osgarby, S. M. (2001). The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 303–315.

Smith, E. P., Prinz, R. J., Dumas, J. E., & Laughlin, J. (2001). Latent models of family processes in African American families: Relationships to child competence, achievement, and problem behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 967–980.

Spoth, R., Clair, S., Greenberg, M., Redmond, C., & Shin, C. (2007). Toward dissemination of evidence-based family interventions: maintenance of community-based partnership recruitment results and associated factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(2), 137–146.

Spoth, R. L., Kavanagh, K. A., & Dishion, T. J. (2002). Family-centered preventive intervention science: toward benefits to larger populations of children, youth, and families. Prevention Science, 3(3), 145–152.

Spoth, R., & Redmond, C. (2000). Research on family engagement in preventive interventions: Toward improved use of scientific findings in primary prevention practice. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 21(2), 267–284.

Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Wong, M., Tu, W., Elliott, M. N., et al. (2003). A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(5), 603–611.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., Bohon, C., Marti, C. N., & Rohde, P. (2009). A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: Factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 486–503.

Stormshak, E. A., Dishion, T. J., Light, J., & Yasui, M. (2005). Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: Linking service delivery to change in student problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 723–733.

Strengthening Families Program. (2010). Accessed January 1, 2010 from http://www.strengtheningfamiliesprogram.org/.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2006). Children in the Middle: Divorce Education for Parents. Downloaded January 1, 2010 from http://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=5.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2007). An Action Plan for Behavioral Health Workforce Development; Executive Summary. Downloaded January 1, 2010 from http://www.annapoliscoalition.org/pages/default2.asp?active_page_id=80.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administrator (SAMHSA). (2011) National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices. Downloaded August 1, 2011 from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov.

The Prevention Research Center for the Promotion of Human Development: Ten-year anniversary report. (1998–2008). Downloaded August 1, 2011 from http://www.prevention.psu.edu/.

Tolan, P., Gorman-Smith, D., & Henry, D. (2004). Supporting families in a high risk setting: Proximal effects of the SAFEChildren preventive intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 855–869.

Tolan, P. H., & McKay, M. M. (1996). Preventing serious antisocial behavior in inner-city children: An empirically based family intervention program. Family Relations, 45(2), 148–155.

Tremblay, R. E., McCord, J., Boileau, H., Charlebois, P., Gagnon, C., LeBlanc, M., et al. (1991). Can disruptive boys be helped to become competent? Psychiatry, 54, 148–161.

University of Connecticut’s Family Development Credential Program. (2010). Accessed January 1, 2010 from http://www.familydevelopmentcredential.org/.

Visiting Nurse Association of America. (2010). Accessed January 1, 2010 from http://vnaa.org/vnaa/siteshelltemplates/homepage_navigate.htm.

Webster-Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Hammond, M. (2004). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: Intervention outcomes for parent, child, and teacher training. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33(1), 105–124.

Wilhelm, G. (2006). When depression is a family matter. Accessed January 1, 2010 from http://magazine.jhsph.edu/2006/Fall/news_briefs/depression/?subsection_id=50.

Wilson, S. J., Lipsey, M. W., & Derzon, J. H. (2003). The effects of school-based intervention programs on aggressive behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 136–149.

Wolchik, S. A., Sandler, I. N., Millsap, R. E., Plummer, B. A., Greene, S. M., Anderson, E. R., et al. (2002). Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorced: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 288(15), 1873–1881.

Wolchik, S. A., Schenck, C. E., & Sandler, I. N. (2009). Promoting resilience in youth from divorced families: Lessons learned from experimental trials of the New Beginnings Program. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1833–1868.

Wolchik, S. A., West, S. G., Westover, S., Sandler, I. N., Martin, A., Lustig, J., et al. (1993). The Children of Divorce Parenting Intervention: Outcome evaluation of an empirically based program. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(3), 293–331.

Woods, E. R., Samples, C. L., Melchiono, M. W., Keenan, P. M., Fox, D. J., Chase, L. H., et al. (1998). Boston HAPPENS Program: A model of health care for HIV-positive, homeless, and at-risk youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 23(2), 37–48.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Grants No. This R21MH90146-01 and P20 MH 078178-0, both from the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH). We wish to thank Maura Crowe for her contribution to this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cavaleri, M.A., Olin, S.S., Kim, A. et al. Family Support in Prevention Programs for Children at Risk for Emotional/Behavioral Problems. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 14, 399–412 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0100-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0100-9