Abstract

In Alemannic dialects of German, [n] is particularly vulnerable to assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis. Although these changes are not necessarily uniform across all Alemannic varieties, the Alemannic dialect areas all exhibit some, if not all, of these processes. In this article, we present data from a diverse array of Alemannic dialects and show that [n] behaves similarly throughout Alemannic, assimilating to the place of following stops, deleting word-finally, and repairing hiatus through epenthesis. We contend that coronal [n] is interacting with so many processes because it is unmarked in terms of place and manner. This paper contributes to the phonological literature on dialectology and Markedness Theory. First, by considering similar processes which occur across multiple Alemannic dialects, we show how Alemannic prefers eliminating or modifying word-final [n]. Second, this analysis gives insight into theories of segment (un)markedness; thus, the data presented in this paper support descriptions of unmarked segments as undergoing assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis, while they challenge markedness accounts by scholars who bar [n] as an epenthetic segment. Third, we provide data for a language family in which one segment undergoes all three processes of assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis; this is unprecedented in the literature on unmarked segments, which typically focuses on languages which possess only one of these three processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This article examines several processes involving the coronal nasal in Alemannic dialects of German. Alemannic is a dialectological and historical classification of German dialects spoken in Switzerland, France (Alsace), western Austria (Vorarlberg), Liechtenstein, and southwestern Germany (Baden-Württemberg and Bayerisch-Schwaben). Alongside Bavarian German and East Franconian, Alemannic is classified as Upper German. Alemannic dialects are typically divided into Swabian, Low Alemannic, Central Alemannic, High Alemannic, and Highest Alemannic, with numerous transitional zones between dialect areas. Even though Alemannic dialects may differ substantially from one location to another, there are certain characteristics which, despite some exceptions, unify Alemannic dialects, such as extensive shifting of obstruents via the High German Consonant Shift, the lack of monophthongization of MHG diphthongs, the retention of MHG long high monophthongs, and the loss of unstressed schwa by syncope or apocope (Salmons 2012, 244).

While there is great variation within Alemannic, many Alemannic dialects show a preference for altering coda /n/ via processes such as assimilation and deletion, as well as inserting [n] in hiatus. In (1a), assimilation is exemplified by the shift in place of the nasal at the end of ‘muŋ’ from underlying coronal to velar. Deletion takes place in (1b), where the underlying nasal does not surface in word-final position. In (1c), a process of epenthesis causes [n] to surface in hiatus.Footnote 1

These data illustrate the flexibility of the coronal nasal in Alemannic. The coronal nasal /n/ has been demonstrated in the literature on Swiss dialectology to “disappear” syllable-finally (Keller 1961, 52–54); to be “introduced -- or preserved, if seen historically” and to behave as “mobile” (referring to its surfacing in sandhi-derived hiatus, Keller 1961, 54); and to join other coronals in place assimilation (Keller 1961, 53–54).

We interpret these various processes to be indicative of a common phonological motive. This openness to phonological transformation leads us to conclude that /n/ is unmarked in Alemannic. Specifically, /n/ is like other coronals, such as /t/, which have been argued to be unmarked because they are coronal (Paradis and Prunet 1991b and numerous others). Many proposals have been put forth concerning how to express coronal unmarkedness formally, such as coronal underspecification in autosegmental phonology or markedness constraint rankings in Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993; de Lacy 2006) penalizing noncoronals more harshly than coronals; however, capturing markedness theory formally is not the goal of the present paper.Footnote 2 Instead, we show that there are three processes (assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis)Footnote 3 which, when seen as diagnostics, together indicate that /n/ is unmarked in Alemannic. In terms of place of articulation markedness, /t/ is generally considered to be the least marked stop cross-linguistically because it undergoes assimilations, deletions, and epentheses in various languages; however, to our knowledge, there is no one language in which /t/ undergoes all three processes, whereas that is precisely the situation for /n/ in Alemannic.

In this article, we address the following questions:

-

A.

Which segments does /n/ assimilate to in each dialect, and is this assimilation the same throughout Alemannic?

-

B.

In which context(s) does /n/ delete? What motivates deletion of /n/?

-

C.

In the case of hiatus resolution, why is [n] inserted and not some other segment?

-

D.

Which extant phonological principles can account for all of the diverse processes interacting with the same segment?

Concerning question D, we will show how the Alemannic data reflect Rice’s (2007) description of unmarked segments, wherein she summarizes literature which indicates that unmarked segments are likely to be epenthetic, targets of assimilation, and lost in deletion. This differs from conclusions in de Lacy (2006), who explicitly states that his theory “cannot produce a language with an epenthetic nasal in onsets” (de Lacy 2006, 103).

In the following sections, we discuss source material for the Alemannic dialects presented in this paper (Sect. 2) and address each of the three changes listed above: Nasal Place Assimilation is examined in Sect. 3; examples concerning n-Deletion are investigated in Sect. 4; and Linking-n is examined in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, we synthesize these various strands of argumentation into an analysis, which argues that markedness theory accounts for the behavior of /n/. That analysis does not discuss how markedness is accounted for formally (e.g., underspecification vs. constraint hierarchies) because it is focused on the implications of the remarkable finding that /n/ is behaving as an unmarked segment via three processes within one dialect region. Section 7 concludes.

2 Source material

Data examined in this article come from a survey of Alemannic dialects. In order to ensure that a typologically and geographically broad array of Alemannic is represented, we elicited references from each major and minor group of Alemannic. From Highest Alemannic, the dialects of Visperterminen and Glarus were chosen; from High Alemannic, Zürich, Bern, and Todtmoos-Schwarzenbach Alemannic were selected as representative. We chose Alsatian (Strasbourg) as the Low Alemannic representative, and data for the Swabian and Central Alemannic dialects were drawn from Horb am Neckar and Villingen-Schwenningen, respectively. We also consulted survey works of Alemannic dialects, such as Keller (1961), Russ (1989a, b), Streck (2012). The reason for this diverse selection is to present a typological survey which could make claims about Alemannic generally, and not merely about one dialect within Alemannic. Although differences between these dialects can be drastic, we argue that [n] behaves similarly in each dialect, and at least some of the processes discussed in this article can be observed in all dialects. The linguistic and geographic location of each dialect is shown in Fig. 1.

Data are drawn from the geographically diverse array of Alemannic dialects shown in Fig. 1. In Wiesinger’s (1983) dialectological terms, these consist of A1 Alemannic (Highest and High Alemannic), A2 Alemannic (Low Alemannic), and A3 Alemannic (Swabian and ‘Vorschwäbisch’, or Central Alemannic).Footnote 4 In Table 1, we provide dialect classifications for each of the sources we use throughout this paper. The classification of these dialects as ‘Highest’, ‘High’, ‘Low’, ‘Swabian’, and ‘Central Alemannic’ come from Wiesinger (1983).

Despite various regional distinctions, the phonological processes we describe here can be considered pan-Alemannic, even if not equally instantiated in each regional variety. We interpret these various processes involving [n] as evidence that [n] is particularly malleable in Alemannic, free to be inserted or deleted according to the needs of syllable structure and free to share its place of articulation with adjacent segments (and in some cases across vowels).

Specifically, Nasal Place Assimilation appears to be ubiquitous throughout the dialects of Alemannic. The process of word-final n-Deletion is almost as ubiquitous, though in Low Alemannic it only affects weakly stressed syllables. Finally, n-Epenthesis in hiatus affects all dialects under consideration except Visperterminen.

Past research by Nübling and Schrambke (2004) has shown that within the Alemannic dialect continuum, there exists a bell-shaped linguistic barrier (Sprachschranke) which divides Alemannia into two regions: southern Alemannic (in Wiesinger’s classificational schema: Highest, High, and Central Alemannic) is classified as a syllable-counting dialect area (silbensprachlich), while northern Alemannic (Swabian and Low Alemannic) is classified as a stress-counting (akzentsprachlich) dialect area.Footnote 5 This bifurcation is based on observations of how each region treats various processes: within the bell-shaped southern region, geminate consonants are generally preserved, the fortis/lenis distinction is better preserved, and place assimilation across word and morpheme boundaries is possible. In the north, geminate consonants have been reduced, the fortis/lenis distinction is no longer clearly that of consonantal strength, and place assimilation is only possible within a morpheme or when previous morpheme boundaries have become opaque.Footnote 6 Thus, while we speak broadly about Alemannic, it should be emphasized that the distinctions between, for example, High Alemannic and Swabian are by no means trivial, and in fact weigh in on discussions of place assimilation and syllable optimization. Therefore, while arguing that the processes exemplified by (1) are present in Alemannic generally, we concede that their instantiation based on morphophonemic restrictions such as possible syllable templates and boundary marking may vary widely from dialect to dialect.

In the following sections, we present data exemplifying the processes investigated here which involve [n], specifically, Nasal Place Assimilation, n-Deletion, and Linking-n.

3 Nasal place assimilation

Many authors have noted that coronals tend to exhibit special behaviors and characteristics (see, for example, Paradis and Prunet 1991b; Hall 1997, 2011; Grijzenhout 1998). One of the most common of these behaviors is that coronals regularly undergo place assimilations (see Kiparsky 1985; Avery and Rice 1989; Hall 2011, 2020; Würth 2020, among others). As Würth (2020, 42) states, “coronals are notorious for place assimilation”. A frequently cited example of (coronal) place assimilation is in the English prefix ‘in-’, data for which can be seen in (2).

(2) | Nasal Place Assimilation in English prefix ‘in-’ (Baković 2007, 335) | ||

a. | inapplicable | [næ] | |

b. | impossible | [mp] | |

imbalance | [mb] | ||

c. | intolerable | [nt] | |

indecent | [nd] | ||

d. | inconceivable | [ŋk] | |

ingratitude | [ŋɡ] | ||

In (2a,c) ‘in-’ surfaces with the coronal nasal preceding a vowel or a coronal stop, respectively. In (2b,d), however, [n] assimilates to the place of a following stop; the labial nasal [m] is realized in (2b) before [p, b], and the velar nasal [ŋ] surfaces before [k, ɡ] in (2d).

Some authors examine these behaviors through the lens of underspecification theory, whereby coronals are less specified for place features than noncoronal or peripheral segments (cf. Davis 1991; Yip 1991), and Féry and Meier (1993) give this explanation for place assimilation specifically with reference to Zurich German. As we later discuss in Sect. 6, we account for these behaviors with an analysis in terms of markedness (cf. Kean 1975; Paradis and Prunet 1991a, among others).

Nasal Place Assimilation (NPA) is common in many languages, including Standard German (Wiese 1996, 218–224; Hall 2020, 12ff). Data for Standard German NPA can be seen in (3), where the place of articulation of a nasal stop is shared with the following oral stop. (3a) shows a velar nasal-stop cluster, (3b) coronal, and (3c) labial. The predictability of the place of articulation of pre-plosive nasals is the strongest justification for the rule of NPA in Standard German. With a few exceptions,Footnote 7 nasals simply do not contrast with one another before tautomorphemic plosives.

(3) | Regressive NPA in Standard German (Wiese 1996, 218) | |||

a. | Ba[ŋ]k | Bank | ‘bank’ | |

b. | Ha[n]d | Hand | ‘hand’ | |

c. | Te[m]po | Tempo | ‘tempo’ | |

German dialects, including varieties within the Alemannic dialect continuum, frequently have a rule of NPA.Footnote 8 See, for example, the data in (4) which show NPA across word and morpheme boundaries in the Highest Alemannic dialect described by (Wipf 1910).Footnote 9

(4) | Regressive NPA in Visperterminen (Wipf 1910)Footnote 10 | ||||

a. | wɛn d wilt | wenn du willst | ‘if you like’ | 140 | |

| trinken tut es | ‘drinking does it’ | 112 | ||

in dr fɑmíli | in der Familie | ‘in the family’ | 112 | ||

fɑn trɑtshɑfti | aus Trotz | ‘out of defiance’ | 112 | ||

b. | úmpɑrr | unpaarig | ‘unpaired’ | 112 | |

öiɡumblikχ | Augenblick | ‘blink of the eye’ | 112 | ||

fɑm bēšer šōrt | von böser Sorte | ‘of bad breed’ | 112 | ||

c. | špɑŋɡriə | Grünspan | ‘green rust’ | 44 | |

| Ungnade | ‘disgrace’ | 112 | ||

fɑŋ ɡiburd | von Geburt an | ‘from birth on’ | 112 | ||

In (4a), the coronal nasal surfaces as coronal [n] when a coronal stop [t, d] follows; this pattern follows for labial and dorsal, where in (4b), the coronal nasal surfaces as [m] before labial [p, b] and as dorsal [ŋ] before [ɡ] in (4c). The prevalence of NPA in this dialect can be seen particularly well in the word von ‘from’, which has three different realizations, depending on the following stop. It can be seen in the data in (4) that when a coronal stop follows, von is realized as [fɑn]; when a labial follows, it surfaces as [fɑm]; and when a dorsal follows, it surfaces as [fɑŋ].Footnote 11 Alternations like those in von are evidence that NPA is a synchronic process in Alemannic.

Data sets (5–8) show Regressive NPA in four other Alemannic dialects. In each data set, there are examples of homorganic nasal-stop clusters similar to those for Visperterminen above.Footnote 12

(5) | Regressive NPA in Bernese Seeland (Baumgartner 1922) | ||||

a. | hɑnd | Hand | ‘hand’ | 106 | |

b. | ummüɡlǝxFootnote 13 | unmöglich | ‘impossible’ | 124 | |

c. | uŋkšoxxǝ | unerschrocken | ‘unabashed’ | 124 | |

miŋkot | mein Gott! | ‘My God!’ | 124 | ||

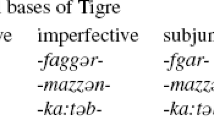

(6) | Regressive NPA in Horb Swabian (Kauffmann 1890) | ||||

a. |

| Handel, Streit | ‘conflict’ | 56 | |

| Schwänze | ‘tails’ | 57 | ||

b. |

| handvoll | ‘handful’ | 43 | |

c. |

| und gar | ‘and completely’ | 268 | |

(7) | Regressive NPA in Todtmoos-Schwarzenbach (Kaiser 1910) | ||||

a. | hambflə | Handvoll | ‘handful’ | 35 | |

b. | xyŋk | König | ‘king’ (in a game) | 37 | |

Würth (2020, 113) also describes NPA in Zurich German, stating that “When followed by an obstruent consonant, ... we only find homorganic nasal-obstruent clusters.” The data she provides, reproduced here in (8), illustrate this.Footnote 14

(8) | Regressive NPA in Zurich German (Würth 2020) | ||||

a. | pːlompǝ | Plombe | ‘filling’ | 113 | |

b. | ʋæntǝ | wenden | ‘turn around’ | 113 | |

c. |

| Kongo | ‘Congo’ | 113 | |

As Gordon (2016, 124) states: “Among cases of consonant-consonant assimilation, there is a clear typological bias in favor of regressive assimilation, in which one or more features spread backward from one sound to a previous sound, over progressive assimilation entailing the forward spreading of a feature...”. This “typological bias” bears out in both Standard German, as well as German dialects, where Regressive NPA is a much more common and less restricted process than Progressive NPA. In Standard German, for example, Progressive NPA applies only when the nasal is syllabic; see data in (9) for examples of this.Footnote 15

(9) | Progressive NPA in Standard German (Wiese 1996, 222) | ||

[ɡeːbm̩] | geben | ‘to give’ | |

[tʀaːɡŋ̩] | tragen | ‘to carry’ | |

[laɪ̯tn̩] | leiten | ‘to lead’ | |

When Progressive NPA occurs in Alemannic German, it tends to be less restricted than Standard German, in that it can occur across vowels; despite this, it is still much less common than Regressive NPA. The data in (10) exemplify distance Progressive NPA in Alemannic.

In data from two different dialects, the coronal nasal is shown to assimilate place progressively from the word-initial labial stop [b] in (10a,b). Similarly, in (10c), the coronal nasal is realized as dorsal after assimilating place progressively from the word-initial dorsal stop [k]. The coronal nasal assimilates dorsal in (10d) as well, in these examples from the fricative [x]. Such a distant progressive assimilation is not found in the standard language.

While /n/ assimilates place progressively and regressively, the nasals of other places of articulation (i.e., labial /m/ and velar /ŋ/) do not. Würth’s (2020, 42–43) recent analysis of Zurich German describes only coronal nasals assimilating place and not the other way around (i.e., labial and velar nasals do not undergo place assimilation). See also the data in (11), which show in (11a) a labial nasal preceding a coronal stop and in (11b) the velar nasal surfacing before a coronal stop; that is, these nasals are not homorganic with the following stop.Footnote 16

Table

2 depicts our findings concerning Regressive NPA in Alemannic. The dialect (from Table 1) is given in the first column, followed by NPA of each of the three nasals.

As Table 2 shows, NPA in Alemannic is restricted to coronals. No dialect studied here possesses an NPA process whereby labials or dorsals undergo assimilation, and all dialects of Alemannic have some NPA which affects the place of articulation of the coronal nasal.

4 Coronal nasal deletion (n-deletion)

In addition to place assimilation showing a strong preference for targeting [n] in Alemannic, deletion also shows a preference for targeting coronal nasals. In this section it is shown that deletion of the coronal nasal [n] syllable-finally is characteristic of Alemannic in general (Streck 2012, 138), although this process is also attested in other dialects, particularly the Upper German varieties (Schirmunski 1962). Schirmunski (1962, 381–384) thoroughly details the loss of nasals before fricatives in German dialectsFootnote 17as well as the loss of final -n (Schirmunski 1962, 385–390). Schirmunski notes that in words like Wein and mein, the final -n is absent in most varieties of Hessian, in the Eastern Palatinate, in southern Thuringia, in the Vogtland, in Upper Franconian, in Upper Alsatian, in Swabian, and in Bavarian. The loss of [n] is also attested in Pennsylvania Dutch, whose phonology has been shaped in part by Alemannic and Franconian dialect features. Reed (1947, 289) attributes final m-loss in certain varieties of Pennsylvania Dutch (western Berks County and Lebanon County) to Alemannic influence (e.g., Bode in western Berks County vs. Bodem in Lehigh County).Footnote 18The most widespread form of n-Deletion deletes coda-n in unstressed syllables, though n-Deletion in stressed syllables is also attested.Footnote 19 We interpret these deletions as instantiations of a broad n-Deletion process active to differing degrees in these differing prosodic domains and targeting an unmarked segment ([n]).

4.1 n-Deletion in unstressed syllables

Alemannic dialects are characterized by the deletion of coronal nasals in the coda. In unstressed syllables, this has led to the reduction of verbal paradigms and the declinational and inflectional endings of nouns and adjectives. The dataset in (12) demonstrates word-final n-Deletion in unstressed syllables in Alemannic.

(12) | /n/-Deletion in unstressed syllables | |||||

a. | mɑxxu | machen | ‘to do, make’ | (Wipf 1910) | 113 | |

xɛnnu | können | ‘to be able to’ | (Wipf 1910) | 113 | ||

b. |

| mahnen | ‘to urge’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 77 | |

ræɡnǝ | regnen | ‘to rain’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 90 | ||

c. | bīsə | beissen | ‘to bite’ | (Kaiser 1910) | 21 | |

| blasen | ‘to blow’ | (Kaiser 1910) | 19 | ||

d. | bɑxə | backen | ‘to bake’ | (Kauffmann 1890) | 116 | |

ǭbət ̔ | Abend | ‘evening’ | (Kauffmann 1890) | 116 | ||

e. |

| arbeiten | ‘to work’ | (Winteler 1876)Footnote 20 | 80 | |

| sterben | ‘to die’ | (Winteler 1876) | 81 | ||

f. | ewwe | eben | ‘flat, even’ | (Sütterlin 1892) | 58 | |

mache | machen | ‘to do, make’ | (Sütterlin 1892) | 58 | ||

The examples in (12) demonstrate how widespread this process is, from Highest Alemannic in (12a) (Wipf 1910) to Low Alemannic in (12f) (Sütterlin 1892). Most of the examples in (12) demonstrate the deletion of [n] in the infinitival suffix represented orthographically in the standard language as -en, as in Berner Seeland [mɑːnǝ] ‘to urge’, Standard German mahnen. The Highest Alemannic examples show that n-Deletion is not contingent upon the preceding vowel being schwa, as it occurs after [u] in Visperterminen [mɑxːu] ‘to do’.Footnote 21

Given that n-Deletion in unstressed syllables has been occurring for centuries (in manuscripts, at least since the High Middle Ages, Kauffmann 1890, 171), it might seem jarring to suggest that it is still a synchronic process. When discussed at all, surveys of Alemannic describe the loss of -n in infinitives, for example, as historical (e.g., Philipp and Bothorel-Witz 1989, 319 for Low Alemannic) or simply take for granted that no -n is underlying (e.g., Russ 1989a for Swabian; Russ 1989b for High Alemannic; Würth 2020 for Zurich German). Furthermore, Russ (1989b, 371) describes final -n as ‘mobile’ (citing Keller 1961, 54) and ‘intrusive’, suggesting that it has not entirely been lost to time.

However, the historical loss of [n] in the coda of unstressed syllables does not constitute evidence against it being a synchronic process. Compare, for example, synchronic [n]-zero alternations provided by Wipf (1910), such as  tüots trinken tut es ‘drinking does it’ (Wipf 1910, 112), where the coronal nasal surfaces before [t] and alternates with the infinitive form

tüots trinken tut es ‘drinking does it’ (Wipf 1910, 112), where the coronal nasal surfaces before [t] and alternates with the infinitive form  trinken ‘to drink’ (Wipf 1910, 45), where the final [n] is deleted when the word surfaces in isolation. In fact, the most comprehensive theoretical analysis of n-zero alternations (Ortmann 1998) posits an underlying /n/ (a ‘floating segment’ in that analysis) which is not associated with a C slot, and therefore only surfaces where one may be licensed from its surroundings, such as in hiatus. Ortmann rejects the notion that n-zero alternations represent a general rule of deletion because certain words retain word-final [n] in the coda. When alternations exist, Ortmann (1998, 67) states that [n] is “present in the underlying representation” but “not associated with a syllable position,” meaning that the underlying segment cannot be parsed. We consider this solution dissatisfying for two reasons: first, it requires syllabification to be present in the underlying representation; and second, it requires certain words to be lexically specified for alternation or non-alternation. As is clear from the discussion above, n-Deletion in unstressed syllables is obligatory, and as will be discussed below, n-Deletion in stressed syllables is pervasive, especially when the syllable is heavy.

trinken ‘to drink’ (Wipf 1910, 45), where the final [n] is deleted when the word surfaces in isolation. In fact, the most comprehensive theoretical analysis of n-zero alternations (Ortmann 1998) posits an underlying /n/ (a ‘floating segment’ in that analysis) which is not associated with a C slot, and therefore only surfaces where one may be licensed from its surroundings, such as in hiatus. Ortmann rejects the notion that n-zero alternations represent a general rule of deletion because certain words retain word-final [n] in the coda. When alternations exist, Ortmann (1998, 67) states that [n] is “present in the underlying representation” but “not associated with a syllable position,” meaning that the underlying segment cannot be parsed. We consider this solution dissatisfying for two reasons: first, it requires syllabification to be present in the underlying representation; and second, it requires certain words to be lexically specified for alternation or non-alternation. As is clear from the discussion above, n-Deletion in unstressed syllables is obligatory, and as will be discussed below, n-Deletion in stressed syllables is pervasive, especially when the syllable is heavy.

We contend that n-Deletion in unstressed syllables is still synchronically active, and its sister change discussed in Sect. 4.2 is alive and well. Both point to a dispreference for coda-[n] in Alemannic, merely in different prosodic domains.

4.2 n-Deletion in stressed syllables

Many dialects of Alemannic also delete coronal nasals in the coda of stressed syllables. For example, in Streck’s (2012) analysis of spontaneous speech data in the Alemannic dialects of Baden-Württemberg, for high-frequency words Wein, bin, Mann, and Neun, deletion of coda [n] was obligatory or variable in 80% to 92% of sampled locations.Footnote 22 Horb Swabian is one such dialect, deleting a coronal nasal in a word-final stressed syllable, as shown in (13).

(13) | Obligatory [n]-Deletion (Kauffmann 1890) | |||

| schön | ‘lovely’ | 160 | |

| Mann | ‘man’ | 160 | |

| kann | ‘can-inf’ | 160 | |

In (13), a word-final coronal nasal consonant does not surface; however, it surfaces when a vowel-initial word (or pronominal clitic) follows, as Kauffman makes explicit by distinguishing [ ] kann from [

] kann from [ ] kann ich.Footnote 23 Examples showing [n]-zero alternations are evidence that word-final n-Deletion in a stressed syllable is a synchronic process. Far from being limited to Swabian, this process is present in many Alemannic dialects, as is visible in (14).

] kann ich.Footnote 23 Examples showing [n]-zero alternations are evidence that word-final n-Deletion in a stressed syllable is a synchronic process. Far from being limited to Swabian, this process is present in many Alemannic dialects, as is visible in (14).

(14) | Coronal nasal deletion in other dialects | |||||

a. |

| Bahn | ‘train’ | (Wipf 1910) | 47 | |

sũ | Sohn | ‘son’ | (Wipf 1910) | 47 | ||

| Bein | ‘leg, bone’ | (Wipf 1910) | 47 | ||

b. | wı̄ | Wein | ‘wine’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 124 | |

| Bein | ‘bone’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 124 | ||

c. |

| Bahn | ‘train’ | (Winteler 1876) | 69 | |

| Hahn | ‘rooster’ | (Winteler 1876) | 69 | ||

\( \underline{\hbox{i}} \) | ein | ‘one’ | (Winteler 1876) | 71 | ||

d. |

| Bahn | ‘train’ | (Haag 1898) | 39 | |

| schön | ‘beautiful’ | (Haag 1898)Footnote 24 | 27 | ||

These dialects also contain synchronic [n]-zero alternations, such as bei Bein ‘bone’, where [n] is deleted, which alternates with surface [n] in the diminutive form beinli Beinchen ‘little bone’ (Baumgartner 1922, 124).

For the non-coronal nasals, nasal deletion is not a regular occurrence. For example, in Horb Swabian, deletion of [m] is merely optional, as is shown in (15). The examples in (15a) show the labial nasal in the coda, but the examples in (15b) show that it may delete.Footnote 25

(15) | Optional [m]-Deletion in Horb Swabian (Kauffmann 1890) | ||||

a. |

| lahm | ‘lame’ | 160 | |

bō̃m | Baum | ‘tree’ | 160 | ||

krō̃m | Kram | ‘junk’ | 160 | ||

b. | rọ̄̃ | Rahm | ‘cream’ | 160 | |

| Blume | ‘flower' | 161 | ||

Glarus (Highest Alemannic) also has what appears to be an optional deletion of labial nasals, as shown in (16). The examples in (16a) correspond to an etymological labial nasal which has now deleted. The examples in (16b) show those same morphemes with the labial nasal preserved. Recall from (14c) that Glarus has a deletion of [n] which is completely regular.

(16) | Optional [m]-Deletion in Glarus (Winteler 1876) | ||||

a. | h&i | heim | ‘home’ | 74 | |

h&nn&-tar& | Hühnerdarm | ‘stellaria media’ | 74 | ||

b. | h&ümli | heimlich | ‘secretive’ | 74 | |

tar&m | Darm | ‘gut’ | 74 | ||

Winteler (1876) attributes the loss of the word-final nasal in these words not to [m]-loss, but to the shift of [m] to [n] in certain words, which provided new inputs for n-Deletion. For the purposes of this article, whether this represents sporadic [m]-loss or regular [n]-loss following a shift to coronal is unimportant because both would point to [n] being less marked than [m].

Like the labial nasal, the velar nasal [ŋ] can occur word-finally in dialects which delete coronal nasals regularly. The velar nasal is retained more readily than the labial nasal, apparently never being subject to deletion. The representative examples in (17) illustrate [ŋ]-retention word-finally. Note that Horb Swabian, which has obligatory n-Deletion and optional m-Deletion, has no such deletion of the velar nasal in a similar prosodic position.

(17) | [ŋ] occurs word-finally (Kauffmann 1890) | ||||

| spring | ‘jump!’ | 268 | ||

| gehe | ‘go!’ | 268 | ||

| langweilig | ‘boring’ | 268 | ||

The only context in Horb Swabian where the velar nasal deletes is before a velar stop in the coda.Footnote 26 Table 3 details the various contexts for nasal deletion in the dialects discussed. ‘Coda-n Deletion (σ)’ means coda n-Deletion in an unstressed syllable, while ‘Coda n-Deletion ('σ)’ means coda n-Deletion in a stressed syllable.

As can be seen in Table 3, word-final n-Deletion is pervasive, both in unstressed syllables and in stressed syllables. While the coronal nasal undergoes regular deletion, labial and velar nasals are not subject to the same rules. Word-final m-Deletion is found in more than half of the dialects under investigation, but is sporadic or otherwise made complicated by competing analyses (such as an earlier shift to [n] or hypothesized analogical restoration). We remain agnostic with respect to these counterproposals and merely point to the fact that the coronal nasal is lost more readily than any other nasal. In fact, as Table 3 makes explicit, there was no word-final [ŋ]-loss in any dialect studied.Footnote 27 Velar nasals hardly delete at all, and when they do, they are immediately preceding an obstruent in the coda, indicating that the nasal may not be underlyingly velar (see note 31). These observations concerning the three nasals converge on one explanation: that the coronal nasal enjoys a special status in Alemannic dialects. This special status means that it may be deleted regularly and in a broader array of contexts than other nasals.

Coronal nasal Deletion can be visualized regionally according to the following maps in Fig. 2, from linguistic atlases. Both maps are depictions of the same word, Mann ‘man’, in various dialects. The first map (Fig. 2A) is a map of Southern Germany and Eastern France, hand-drawn by Georg Wenker, where the predominant form in the Alemannic region is one without a word-final nasal, namely Ma, with a nasalized vowel. This is not true of Low Alemannic, which is situated within the Mann region (i.e., where the coronal nasal is not deleted). However, even in Low Alemannic there are many instances of empty rings in this area, a symbol which in this map means that the word-final [n] has been lost. The second map (Fig. 2B) is a depiction of Switzerland. Each triangle on this map represents a data point. Broadly speaking, the white (empty) triangles represent pronunciations without [n] at the end, while the black (filled) triangles represent pronunciations with [n].

As can be seen in Fig. 2A, the word Mann in the Alemannic dialect region in Wenker's time is most commonly produced with an open syllable. The Central Alemannic and Swabian dialect regions show deletion of [n] and nasalization of the preceding vowel, which Wenker transcribes with a tilde beneath the vowel. These dialects are housed within the pink region drawn by Wenker. The Low Alemannic region (rust-colored), on both sides of the Rhine, generally does not display n-Deletion in this word.Footnote 28

In Switzerland (2B), the deletion of [n] is ubiquitous, as exemplified by the white triangles on the map from the SDS. The black triangles, which represent pronunciations with the final [n], are rare and are found in parts of Highest Alemannic, in the boundary areas of Graubünden, and in two of five dialect islands in Northern Italy. These maps illustrate what is meant by a ‘pan-Alemannic' change: not that it happens exceptionlessly in each dialect, but that the overwhelming majority of datapoints demonstrate n-Deletion.

Section 5 discusses a related process which points to the unmarkedness of [n]: consonantal insertion in hiatus.

5 Linking-n

n-Epenthesis is a common feature of many Alemannic dialects, where an [n] is inserted between vowels in hiatus.Footnote 29 This process, often called Binde-n ‘Linking-n’, is discussed directly by Moulton (1986, 390–391); Ortmann (1998); Nübling and Schrambke (2004, 293ff); Fleischer and Schmid (2006, 248–9); Christen (2019, 257). As described by Moulton, Linking-n is visible in the “fairly regular sandhi alternation between word-final vowel (especially /ə/ in inflected forms) before consonant or pause, but ... vowel plus /n/ before a following vowel.” This section provides data concerning Linking-n, exemplified in (18), where the epenthetic nasal is underlined and in bold face. Note that neither of the epenthetic segments in (18) has an etymological correspondence to an earlier [n] which was deleted.Footnote 30

(18) | Data for Alemannic Linking-n (Nübling and Schrambke 2004, 293–294) | ||

wie-n-er mer… | wie er mir… | ‘how he … to me.dat’ | |

wo-n-er mi g’seh hed | als er mich sah | ‘when he saw me.acc’ | |

In (18), a coronal nasal is present on the surface between two vowels which would otherwise be adjacent; this [n] cannot be the residue of an etymological nasal because these words do not derive from etymological Vn sequences. The coronal nasal, which is subject to deletion, is inserted where it does not otherwise belong. Despite the fact that other consonants delete in coda position,Footnote 31 the coronal nasal alone is eligible to serve as a hiatus-filler. We interpret this as a further indication of the relative unmarkedness of the coronal nasal.

As with NPA and n-Deletion discussed above, n-Epenthesis in Alemannic is a synchronic process. Multiple grammars give examples of [n]-zero alternations, such as tsuǝ zu ‘to’, where no [n] is present when the word is in isolation, which alternates with tsuǝnım zu ihm ‘to him’, where the epenthetic [n] surfaces in hiatus (Baumgartner 1922, 126). Other data with [n]-zero alternations like this one can be found below.

Ortmann (1998) provides a detailed overview and analysis of Linking-n in Alemannic.Footnote 32 He identifies certain morphosyntactic restrictions on Linking-n. For example, finite verbs may undergo n-Epenthesis to avoid hiatus, as in [i loːn-iχ koː] ich lasse euch gehen ‘I let-you.pl go’, yet monosyllabic participles do permit hiatus, as in [kseː uŋ keχt] gesehen und gehört ‘seen and heard’. The crucial distinction between finite verbs and monosyllabic infinitives is that reduced pronoun clitics may be incorporated into the phonological word of finite verbs (as in gib-mer ‘gimme’ vs. gib mir ‘give me’). This leads Ortmann to the conclusion that any rule of n-Epenthesis in Alemannic must be morphosyntactically limited, in contrast to a broad phonological rule such as r-Epenthesis in English. Specifically, he restricts the hiatus epenthesis rule to clitics of the COMP slot C0 and P0 (preposition). Because the finite verb in V2 languages is fronted to the position of COMP, restricting epenthesis to these morphosyntactic categories accounts for Linking-n in pronominal clitics on prepositions (bəi-n-əm bei ihm ‘at him’), overt complementizers (wie-n-er mer wie er mir ‘as he me’) and fronted finite verbs (gloube-n-em glaube ihm ‘believe him’).Footnote 33

However, there are further contexts for Linking-n which are not captured by Ortmann’s generalization; namely, hiatus following schwa suffixes. This context includes polysyllabic participles (e.g., gang-e-n isch ‘is gone’, Ortmann 1998, 64), infinitival forms (lach-e-n un singe ‘to laugh and sing’, Ortmann 1998, 64), schwa-final nouns (jɒkːǝ-n ɒːlekːǝ ‘put on jacket’, Würth 2020, 45), variation in the indefinite article (e Gschicht ‘a story’ vs. soo-n-e Gschicht ‘a story/such a story’, Ortmann 1998, 64), and inflected adjectives (mit mim dreckige Traktor ‘with my dirty tractor’ vs. mit mim dreckige-n Auto ‘with my dirty car’, Ortmann 1998, 66). To account for Linking-n in these contexts, Ortmann postulates an underlying floating segment [n], not linked to a skeletal C slot, which is only realized when an empty C node is available for linking. This floating segment can therefore only surface in hiatus or is not parsed. His approach requires different underlying positions of the floating segment: it floats before the vowel in the case of the indefinite article, and after the vowel elsewhere. Therefore, Ortmann’s approach, which seeks to capture n-Deletion and hiatus-resolving [n] in a unified fashion, actually requires two different kinds of floating segment and a prosodic domain restriction on n-Epenthesis. We contend that markedness pressures (Sect. 6) toward syllable well-formedness provide a more consistent explanation than Ortmann’s analysis regarding Linking-n.

With respect to deletion, we depart from Ortmann’s analysis. For grammatical simplicity, and because Basel has not historically deleted all instances of [n] in coda position, Ortmann rules out a general rule of n-Deletion. This is premature. As shown in Sect. 4, deletion is quite pervasive, and synchronic [n]-zero alternations abound. Additionally, deletion must be synchronic to account for data from Horb Swabian, namely the contrasting behavior of n-final prepositions (von) and other prepositions (zu).Footnote 34 In these cases, the absence of [n] in words like von ‘from’ when produced in isolation must be due to deletion, not only because the underlying nasal triggers nasalization of the preceding vowel, but also because it triggers progressive nasalization of the vowels of the cliticized pronoun. Linking-n on the other hand does not trigger nasalization.

In dialects where Linking-n is most productive, it applies not only across word boundaries but also across morpheme boundaries (Nübling and Schrambke 2004, 301), even in inflection and derivation. The examples in (19a) show Linking-n in sandhi with enclitic pronouns. Linking-n is also present in (19b), where it resolves hiatus produced by inflection in the present subjunctive of a vowel-final verb stem. Additionally, Linking-n may arise due to derivation in (19c), where the vowel-initial comparative suffix would produce hiatus with a vowel-final adjective.

(19) | Linking-n in Horb Swabian (Kauffmann 1890) | ||||

a. | bəinəm | bei ihm | ‘by him’ | 265 | |

tsuənənə | zu ihnen | ‘to them’ | 265 | ||

wiəni | wie ich | ‘how I’ | 265 | ||

b. | də səinis̆t | du seiest | ‘you be.subj’ | 266 | |

mr səinə | wir seien | ‘we be.subj’ | 266 | ||

se səinə | sie seien | ‘they be.subj’ | 266 | ||

c. | friənər | früher | ‘earlier’ | 266 | |

Linking-n has also introduced a non-etymological [n] into certain lexemes which were originally vowel-initial, possibly under the influence of the indefinite article ein/en ‘a’.Footnote 35 When this indefinite article preceded a vowel-initial word (e.g., ein Eber), [n] from the indefinite article was syllabified into the onset of the following word (ei Neber) and thus spared from n-Deletion. The epenthetic nasal is re-analyzed as belonging to the stem, as in (20).

Linking-n is particularly widespread in Swabian, Central Alemannic, and High Alemannic dialects. In fact, Moulton (1986, 385) states that “The Sandhi phenomena of this [Zurich] variety are typical for most Swiss German dialects.” In these dialects, Linking-n surfaces between vowels which otherwise would be in hiatus.Footnote 36 Data set (21) depicts these [n]-zero alternations quite clearly. Notice that the following word begins with a vowel in each case.Footnote 37

(21) | Examples of Linking-n in Bernese Seeland (Baumgartner 1922) | ||||

a. | tsuǝ | zu | ‘to’ | 126 | |

tsuǝnım | zu ihm | ‘to him’ | 126 | ||

b. | bı̄ | bei | ‘by’ | 126 | |

bı̄nıs | bei uns | ‘by us’ | 126 | ||

In High and Highest Alemannic, there is a strong tendency to insert [n] in hiatus contexts across word boundaries, as seen in (22).

(22) | Examples of Linking-n in Zurich German (Würth 2020) | |||

sini jɒkːǝ-n ɒːlekːǝ | seine Jacke anlegen | ‘(to) put on his jacket.acc’ | 45 | |

ǝn riːfːǝ-n øpfǝl | ein reifer Apfel | ‘a ripe apple.nom’ | 45 | |

Jacke [jɒkːǝ] in the first example of (22) precedes the verbal infinitive anlegen [ɒːlekːǝ], and the schwa of the end syllable would directly precede the low vowel of the prefix an [ɒː], but Linking-n intervenes to repair hiatus across a word boundary.Footnote 38 Data for Linking-n in the Highest Alemannic dialect in Glarus are given in (23).

(23) | Examples of Linking-n in Glarus (Winteler 1876) | |||

won-i | wo ich | ‘where I’ | 73 | |

se̥n išš | so ist es | ‘so it is’ | 73 | |

Recall from Sect. 4.2 that Glarus has both regular n-Deletion and sporadic m-Deletion. Words like Bahn [bɑː] and Hahn [hɑː] have lost their etymological coronal nasals and surface as open syllables. Likewise, words like heim and Odem have also lost their word-final labial nasals: [həi], [ɑːtə]. However, the labial nasal is not eligible for insertion as a hiatus-repairing linking consonant. This suggests that the labial nasal possesses some quality that the coronal nasal does not; namely, markedness.Footnote 39 The velar nasal likewise is never inserted in hiatus. See, for example, Table 4, which compares Alemannic dialects in which nasals are epenthesized in the hiatus context.

As has been mentioned in the foregoing, Linking-n and n-Deletion are in an opaque relationship because n-Deletion feeds the rule of Linking-n. This can cause some cases of apparent n-Epenthesis which are in fact underlying /n/. To put it simply: not all cases of intervocalic [n] are examples of true n-Epenthesis. Examples illustrating an underlying nasal which alternates with zero are given in (24).Footnote 40

(24) | underlying /n/ (not n-Epenthesis) (Kauffmann 1890) | |||

n-Deletion (coda) | n-Retention (onset) | Gloss | ||

|

| ich habe / habe ich | 265 | |

dəfō̃ |

| davon / von ihnen | 265 | |

|

| ich bin / bin ich | 265 | |

In (24), pronominal clitics appear before and after a given word which has a word-final underlying /n/. In isolation, this [n] is not present in the coda, but when a vowel-initial pronominal clitic is appended, the [n] surfaces in the coda. Note that whether the [n] surfaces or not, the stem vowel is nasalized.

How does one know this [n] is underlying and not epenthesized? The answer is clear when one compares the example in (25a) with the example in (25b). [ənə] ‘ihnen’ is a vowel-initial pronominal clitic. When it attaches to a preposition ending in a vowel, hiatus is resolved via n-Epenthesis (25a). The example in (25b), by contrast, is not n-Epenthesis but retention of an underlying /n/. This is visible in the fact that the underlying /n/ in (25b) triggers nasalization.

(25) | Linking-n behaves differently from underlying /n/ in Horb Swabian | ||||

Intervocalic -n | |||||

a. | tsuənənə | zu ihnen | n-Epenthesis, no nasalization | 265 | |

b. |

| von ihnen | Underlying /n/, nasalization | 265 | |

Because an epenthetic [n] cannot trigger nasalization in Horb Swabian, it must be the product of a rule which applies after nasalization would have occurred. In other words, this opaque relationship is due to a counterfeeding ordering of Nasalization preceding n-Epenthesis.

In no dialect known to the authors is [m] ever used as an epenthetic hiatus-breaking segment. In fact, even if one were to analyze [m]-loss as a two-stage process, where [m] first shifts to [n], and then is lost, the shift of [m] to [n] seems to indicate a markedness relationship, where a labial nasal ‘reduces’ to the less marked coronal nasal. In the following section, we propose that [n] possesses a special unmarked status in Alemannic dialects which motivates the various processes discussed thus far.

6 Discussion

In this section, we assert that /n/ is unmarked in both its place of articulation (coronal) and in its manner of articulation (nasal). The former proposal is uncontroversial but must be justified on evidence concerning the entire range of coronal nasals and obstruents. As is shown in the assimilation data below, coronals are indeed less marked than dorsals and labials in Alemannic. What makes the segment /n/ remarkable is not that it undergoes the same assimilatory process as other coronals, but that it undergoes additional assimilatory processes in some Alemannic dialects and is subject to deletion and epenthesis that other coronals do not undergo. Specifically, we find that /n/ in Alemannic accords well with Rice’s (2007) description of unmarked segments and does not align with de Lacy’s (2006) theory with respect to epenthesis.

6.1 Contextualizing Alemannic /n/-Unmarkedness

In the phonological literature, great attention has been given to the concept of ‘markedness’ (see Trubetzkoy 1931, 1939; Jakobson 1941; Chomsky and Halle 1968; Stampe 1972; Prince and Smolensky 1993; de Lacy 2006; Rice 2007, among others), which in phonology refers to the fact that “not all elements in a phonological system are of equal status” (Rice 2007, 79). Unmarked segments are more natural, more common, and easier to learn, while marked segments are less natural, less common, and more difficult to acquire. In phonological terms, unmarked sounds are predicted to be more malleable: ready targets for deletion, coalescence, epenthesis, assimilation, and neutralization (Rice 2007, 80).Footnote 41 In terms of frequency, marked sounds and processes are less likely to occur in the world’s languages, whereas unmarked sounds and processes are more likely to occur cross-linguistically. De Lacy (2006) introduces markedness in terms of ‘avoidance’, where marked structures are avoided, and unmarked structures are generated. He gives the following example: “...many languages have processes which turn the phonological segment /k/ into [ʔ]. In a sense, this process avoids [k] and favors [ʔ], so [k] (or some component of [k]) can be said to be more marked than (some component of) [ʔ]” (de Lacy 2006, 1).

It is an unremarkable finding that coronals are less marked than labials or velars. Data from Alemannic bear out this general observation: Alemannic has a regressive assimilatory process in sandhi whereby coronals assimilate to the noncoronal place of articulation of following stops, fricatives, and nasals. This process produces homorganic surface clusters from underlyingly heterorganic clusters; see the data in (26).Footnote 42

(26) | Place assimilation in sandhi (Keller 1961, 52)Footnote 43 | |||||

a. coronal + coronal | ||||||

d, t + d, t > tt | hä[tː]ankt | hät tankt | ‘has thought’ | |||

b. coronal + postalveolar | ||||||

s + s̆ > s̆ | e[ʃː]reibt | es schreibt | ‘she.dim writes’ | |||

c. coronal + dorsal | ||||||

two-member clusters | ||||||

d, t + g > gg | hä[kː]hürated | hät ghürated | ‘has married’ | |||

d, t + k, kx > kx | [kːx]ind | d Chind | ‘the child’ | |||

three-member clusters | ||||||

nd, nt + g> ngg | hä[ŋkː]ee | händ ggee | ‘have given’ | |||

nd, nt + ch, k> ngkch | si[ŋkx]oo | sind choo | ‘have come’ | |||

d. coronal + labial | ||||||

two-member clusters | ||||||

d, t + b, p > pp | [pː]ruut | d Bruut | ‘fiancée’ | |||

d, t + f > pf | [pf]rau | d Frau | ‘the woman’ | |||

d, t + m > pm | [pm]uetter | d Muetter | ‘the mother’ | |||

three-member clusters | ||||||

nd, nt + b, p > mpp | fi[mpːm]er | findt mer | ‘one finds’ | |||

nd, nt + f, pf > mpf | si[mpf]raue | sind die Fraue | ‘the women are’ | |||

nd, nt + m > mpm | chu[mpm]er | chund mer | ‘one comes’ | |||

The data in (26) show that assimilation is common to all coronal stops and nasals, and to the coronal fricative /s/ before /ʃ/. As Keller (1961, 53) writes, “all dentals are thus assimilated to labials and velars.” Markedness theory offers a concise explanation for this behavior: unmarked segments (coronals) are subject to assimilation to marked segments (labials and dorsals). Note that the nasals appear only in clusters, not because they are exempt from two-member clusters, but because nasals are deleted at the right edge of a word, and thus do not show such alternations across word boundaries unless they are part of a word-final cluster.

Noelliste (2023) recently argued that for the Highest Alemannic dialect of Visperterminen (described by Wipf 1910):

“... /n/ is unmarked in terms of both (a) Place of Articulation and (b) manner. /n/ is therefore a likely candidate for assimilations and deletions, two processes which render the underlying coronal nasal ... unrealized on the surface ... it is argued that markedness of syllabic structure also plays a role. Specifically, VG [Visperterminen German] /n/ and /nn/ undergo the processes detailed above in the syllable coda (which is often considered a more marked syllabic position).” (Noelliste 2023, 31).

The current paper is an expansion of Noelliste’s (2023) case study in two ways. The first expansion here concerns the number of sources and dialects studied; Noelliste (2023) took an in depth look at one source, and thus one dialect (Visperterminen), while we include data and multiple sources from five different Alemannic regions (cf. Table 1). The second way we have expanded upon the previous study is in terms of processes; Noelliste (2023) cited data for assimilation and deletion of the coronal nasal, and we include in this article those two processes, as well as Linking-n.

In a typological cross-linguistic study of 100 languages, Gordon (2016, 128) states that nasals are the most likely consonants to assimilate place (27 of the 100 languages studied). Gordon (2016, 131) also gives manner and place hierarchies (typologically) for assimilations—i.e. which segments are most likely to assimilate. In the place hierarchy, coronals are shown to be most likely to assimilate, and for the manner hierarchy, nasals are most likely to assimilate.Footnote 44 Following a definition of markedness which concerns how (un)common a process or segment is cross-linguistically, or using Gordon’s terms “likely vs. unlikely”, it makes sense then that typologically a coronal nasal would be the most likely target for assimilation, as it is a nexus where both place of articulation and manner hierarchies meet.

Up to this point, we have focused on markedness in terms of place. However, as Noelliste (2023) noted, the data for Alemannic indicate that /n/ may not only be unmarked in terms of its place of articulation, but also in terms of its manner (i.e., nasal). Consider, for example, the other Alemannic coronal consonants /t/, /d/, /s/, /l/, /r/ when they occur word-finally, as in (27).

(27) | Data for non-nasal coronal consonants [non-deletion] | |||||

a. | miŋkot | mein Gott! | ‘My God!’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 124 | |

wɛn d wilt | wenn du willst | ‘if you like’ | (Wipf 1910) | 140 | ||

b. | hɑnd | Hand | ‘hand’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 106 | |

| Ungnade | ‘disgrace’ | (Wipf 1910) | 112 | ||

c. |

| Schwänze | ‘tails’ | (Kauffmann 1890) | 57 | |

tsi̱s | Zins | ‘interest rate’ | (Winteler 1876) | 73 | ||

d. |

| handvoll | ‘handful’ | (Kauffman 1890) | 43 | |

xeŋəl | Kennel | ‘kennel’ | (Weber 1923) | 136 | ||

e. | dūr | durch | ‘through’ | (Kauffman 1890) | 259 | |

tːyːr | Tür | ‘door’ | (Würth 2020) | 28 | ||

As the data in (27) show, the other coronal consonants do not undergo deletion word-finally like /n/ in Alemannic.Footnote 45 There are also no examples of these consonants as epenthetic,Footnote 46 nor does assimilation of these consonants parallel that of Alemannic /n/.

Würth (2020) discusses some interesting behavior of obstruents in Alemannic German. She shows that the past participle prefix velar [kː] undergoes total assimilation when a stop follows. This accords with Winteler’s (1876) account of Alemannic German, in which he argues that “adjacent homorganic stops are produced with a single articulatory gesture” (Würth 2020, 42). The data in (28) show this assimilation of the velar stop, where velar place of articulation is unrealized when the past participle prefix precedes labial [p] (in 28a) or coronal [t] (in 28b). Würth (2020, 42–43) also shows that /t/ undergoes place assimilation to obstruents and nasals across morpheme and word boundaries (see 29); Würth (2020, 43) additionally provides data for place assimilation of alveolar /s/ to postalveolar /ʃ/, given here in (30).Footnote 47

(28) | Assimilations of velar stop (Past Participle) (Würth 2020) | ||||

a. | [pɒxːǝ] | backen | ‘to bake’ | 42 | |

kː + pɒxːǝtː | [pːɒxːǝtː] | gebackt | ‘baked pp’ | 42 | |

b. | [tiǝ̯nǝ] | dienen | ‘to serve’ | 42 | |

kː + tːiǝ̯nǝtː | [tːiǝ̯nǝtː] | gedient | ‘served pp’ | 42 | |

(29) | Assimilation of coronal stop (Würth 2020) | ||||

a. | /hɒnt/ + /præitːi/ | → | [hɒmpːræitːi] | ||

Hantbreite | ‘palm (of the hand)’ | 43 | |||

b. | /kroːsː unt xliː/ | → | [kroːsːuŋkxliː] | ||

groß und klein | ‘large and small’ | 43 | |||

(30) | Assimilation of coronal fricative (Würth 2020) | ||||

/ǝs ʃifː/ | → | [ǝʃːifː] | |||

ein Schiff | ‘a ship’ | 43 | |||

Given the data in (28–29), it appears that Alemannic German stops (not only those which are coronal, but velar [kː] as well) are flexible in their ability to assimilate place;Footnote 48 however, they differ crucially from nasals (especially coronal /n/) in their lack of systematic deletion and epenthesis. Thus, the data would suggest that ‘nasal’ is less marked than ‘plosive’ in Alemannic, particularly in terms of its interactions with deletions and epentheses. Furthermore, the data in (29) differ from those in (28) and (30) in that the assimilation in (29) targets obstruent-nasal clusters, rather than merely coronal stops, which raises the question whether it is the stop or the nasal which triggers the assimilation.

As discussed in previous sections, we consider the processes of assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis in Alemannic to be synchronic (as opposed to diachronic). This analysis is supported by alternations concerning each process, such as those in (31). It can be seen in (31a) that the word von has three realizations, depending on the consonant that follows: when coronal [t] is word-initial in the following word, the coronal [n] surfaces; when labial [b] begins the next word, labial [m] surfaces, and when dorsal [ɡ] follows, dorsal [ŋ] is realized.Footnote 49 In (31b), the word-final /n/ in the infinitive trinken is deleted, unless it is licensed by a following coronal, as in the example trinken tut es.Footnote 50 In (31c), it can be seen that in isolation, zu is pronounced as an open syllable; however, when the following word is vowel-initial, which creates hiatus, an [n] is inserted.

(31) | Synchronic alternations | |||||

a. | fɑn trɑtshɑfti | aus Trotz | ‘out of defiance’ | (Wipf 1910) | 112 | |

fɑm bēšer šōrt | von böser Sorte | ‘of bad breed’ | (Wipf 1910) | 112 | ||

fɑŋ ɡiburd | von Geburt an | ‘from birth on’ | (Wipf 1910) | 112 | ||

b. |

| trinken tut es | ‘drinking does it’ | (Wipf 1910) | 112 | |

| trinken | ‘to drink.inf’ | (Wipf 1910) | 45 | ||

c. | tsuǝ | zu | ‘to’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 126 | |

tsuǝnım | zu ihm | ‘to him’ | (Baumgartner 1922) | 126 | ||

It is important to specify that these are synchronic data and processes, as much of the literature on markedness is also synchronic in nature.

6.2 Markedness theories and Alemannic /n/

De Lacy’s (2006) seminal work on markedness devotes much attention to the idea of ‘markedness pressures’. Two of these pressures are summarized in (32):

(32) | Markedness pressures (de Lacy 2006, 23) | |

a. | Markedness Reduction (MR) | |

There is pressure for output segments to have unmarked features. | ||

b. | Preservation of the Marked (PoM) | |

There is pressure for marked inputs to be preserved faithfully. | ||

De Lacy (2006) works within the framework of Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993), and although we do not offer a theory-specific analysis here, we believe the foundational principles discussed in de Lacy (2006) can be applied within multiple theoretical frameworks. The two pressures in (32) are at odds with each other: a language simultaneously prioritizes the unmarked output (similar to the optimality-theoretic preference to the optimal output) and faithfulness to the input segment. This tug-of-war is expected to be instantiated differently in different languages, and prioritization or relegation of one or the other opposing force in a given markedness domain explains why a language behaves the way it does with respect to markedness.

Another key concept in de Lacy’s (2006) work on markedness concerns hierarchies, where features are ordered from most marked to least marked. Concerning markedness hierarchies, de Lacy (2006, 34) gives the example of the obstruent series, where he states “...there is almost universal agreement that the obstruent voicing hierarchy has voiced obstruents more marked than voiceless ones...”. De Lacy (2006) makes clear that markedness hierarchies can intersect and conflict within a grammar; a language’s satisfaction of the sonority hierarchy, for example, may be overridden by the grammar’s comparatively stronger compulsion to ban voiced segments from the coda. It is important to note that for de Lacy, these hierarchies are universal, yet free to be instantiated in specific languages in different ways. The different rungs on the hierarchy do not strictly dominate one another because they can be conflated; for example, both DORS, LAB > COR or DORS > LAB > COR are possible place hierarchies; this ordering, however, can never be inverted, i.e. *COR > LAB , DORS is not possible.

We can categorize the three phonological processes discussed in preceding sections according to their relevant markedness pressure (either MR from 32a or PoM from 32b) and within which markedness hierarchy the pressure is exerted (place of articulation, sonority, syllable structure), as in (33).

(33) | Processes discussed in this paper | ||

Process | Markedness pressure | Markedness hierarchy | |

a. NPA | PoM | Place of Articulation | |

b. n-Deletion | MR | Syllable structure | |

c. n-Epenthesis | MR | Syllable structure | |

NPA in (33a) is a result of Preservation of the Marked because comparatively more-marked places of articulation (dorsals, labials) win out over less-marked coronals, as in fɑŋ ɡiburd from (31a).

The other two changes in (33), n-Deletion and n-Epenthesis, are both examples of Markedness Reduction in the syllabic domain: both conspire, working on opposite ends of the syllable, to produce a well-formed CV syllable.Footnote 51 Specifically, n-Deletion deletes coda nasals while n-Epenthesis provides onsets to otherwise onsetless syllables. Closed syllables have been argued to be more marked than open syllables (Clements and Keyser 1983; Blevins 1995; Rice 2007, 81, among others), while onsetless syllables have also been argued to be structurally inferior to syllables with onsets (Itô 1989; Kager 1999, 93). Streck (2012, 137) also makes this point concerning n-Deletion: the open (CV) syllable which results from deletion of coda [n] “...kann insgesamt als universalphonologisch unmarkiert angesehen werden.”Footnote 52 This view of universal phonological typology ultimately derives from Jakobson’s (1962, 526) insight that the CV syllable template is present in all human languages, whereas V syllables or CVC syllables are not.

Changes (33b) and (33c) are noteworthy in that they indirectly shed light on the place of articulation markedness hierarchy evinced by (33a). Recall from Sect. 3 that n-Deletion (33b) preferentially targets coronal nasals: labial and velar nasals are not subject to categorical deletion. Similarly, the epenthetic segment in (33c) is a coronal nasal, rather than a labial or velar nasal.

As shown in Table 5, the three processes of assimilation, deletion, and epenthesis can be observed throughout the Alemannic dialect continuum.

While many aspects of de Lacy’s (2006) work shed light on /n/ unmarkedness in Alemannic (see discussion above), the Alemannic data pose a serious problem for de Lacy’s account of markedness; specifically, De Lacy (2006, 103) states explicitly that his account of markedness does not predict n-Epenthesis:

“The theory cannot produce a language with an epenthetic nasal in onsets (unless an adjacent segment is nasal) as an epenthetic onset consonant cannot get a [+nasal] feature through assimilation to oral vowels, and nasals are not the least sonorant segment type.”

The data from Alemannic indicate that nasal consonant epenthesis is a synchronic hiatus repair process. Because de Lacy’s theory does not predict an epenthetic nasal in onsets, we follow different research on Markedness to account for nasal consonant epenthesis.

In her chapter on “Markedness in Phonology”, Rice (2007) summarizes the conclusions of much previous phonological literature, stating that the “chapter focuses on the evidence for a view of featural markedness that relates to contrast...” (Rice 2007, 79). She juxtaposes her chapter with the view of markedness in works by authors such as de Lacy (2006). Rice (2007, 80) gives the phonological properties in (34) for marked and unmarked segments; it can be seen that an unmarked segment is “likely to be epenthetic”, “target of assimilation”, and “lost in deletion”.

(34) | Markedness Diagnostics in Rice (2007, 80) | |

|---|---|---|

Marked | Unmarked | |

subject to neutralization | result of neutralization | |

unlikely to be epenthetic | likely to be epenthetic | |

trigger of assimilation | target of assimilation | |

remains in coalescence | lost in coalescence | |

retained in deletion | lost in deletion | |

Rice (2007) classifies the three processes presented in this paper differently than de Lacy (2006), discussing processes as “phonological diagnostics for featural markedness”. Following Rice (2007), epenthesis is classified as “emergence of the unmarked”, and both assimilation and deletion are classified as “submergence of the unmarked” (cf. de Lacy’s 2006 “preservation of the marked”). Thus, while de Lacy (2006) views markedness through the lens of processes interacting with marked structures, Rice’s (2007) discussion centers on diagnostics which elicit information about what is unmarked. Although Rice (2007) does not present a model per se, her diagnostics concerning segment unmarkedness are illustrative of the three processes outlined above, while de Lacy’s (2006) prediction about [n] not being epenthetic is too strong to account for the Alemannic data. Because assimilation and deletion affect coronal nasals to a greater extent than coronal stops and fricatives, while epenthesis selects nasals (not stops) for hiatus repair, we consider the Alemannic data to be a serious challenge for de Lacy’s theory. However, more research into the intersection of markedness theory and Alemannic dialectology is needed.

Considering all of the data and markedness literature presented here, we propose that /n/ possesses two unmarked traits: it is coronal (which is unmarked), and it is also a nasal stop (where nasal is also considered unmarked). /n/ is phonetically a stop in the sense that the oral tract’s airflow is cut off completely, yet it is a nasal stop, being produced with an open velum. (Non-nasal) stops generally are the unmarked epenthetic segment, whether glottal [ʔ] or coronal [t]; cf. however research by Morley (2015, 2), who states that “...the predicted preference for coronal over dorsal place of articulation [in consonant epenthesis] is not found.”Footnote 53 This is important because [n] is not traditionally considered the least-marked segment when a language’s inventory also includes [t]. Following Krämer and Zec (2020), Alemannic /n/ is likely what they describe as a “low-sonority nasal”, which is a candidate for specification of the feature [continuant]; if, as we argue here, /n/ is phonetically a stop, it could be analyzed as [-continuant] within the Krämer and Zec (2020) framework (cf. also Mielke 2005, who discusses ambivalent behaviors of nasals with respect to the feature [continuant]).Footnote 54

While a full feature-based phonological analysis exceeds the scope of the current paper, we believe that the processes of epenthesis and deletion can be easily accounted for by invoking concepts of syllable structure and sonority. Many scholars have studied principles of sonority dating back to the nineteenth century (see, among others, Sievers 1881; Jespersen 1904; Saussure 1916; Steriade 1982; Zec 1988; Clements 1990; and more recently Parker 2002, 2008, 2011), and discussions of sonority seem intrinsically tied to syllable structure. Generally, syllables rise in sonority from the onset to the nucleus (usually a vowel), and they fall in sonority from the nucleus to the coda (see discussion in Zec 2007; Parker 2011). If we consider Alemannic /n/ to be a low-sonority nasal per Krämer and Zec (2020), then it seems straightforward that Alemannic would insert an [n] in syllable onset position (before an onsetless, vowel-initial syllable) and also delete /n/ in the coda, all in an effort to create well-formed syllables within the phonological system of Alemannic. That is, epenthesis of [n] creates a rise from the onset to the higher sonority nucleus, and deletion of /n/ creates an open syllable (which is often considered the preferred syllable cross-linguistically; cf. literature above).

De Lacy’s (2006) theory explicitly bars [n] as an epenthetic segment, and few languages possess productive n-Epenthesis. Because [n] readily undergoes epenthesis, assimilation, and deletion, we contend that it is in fact unmarked in Alemannic (cf. Rice 2007), and that Alemannic is unique in this under-studied respect.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we presented data from a diverse array of Alemannic dialects. These data all concerned the coronal nasal and illustrated various phonological processes which converge upon a single idea: the coronal nasal is least marked of the consonants in Alemannic. Hence, it may surface in hiatus-resolving epenthesis (n-Epenthesis), it may be deleted in service of syllable well-formedness (n-Deletion), and it may freely assimilate across word and morpheme boundaries (Nasal Place Assimilation). Other nasals (m, ŋ) do not share these liberties.

This paper contributes to the phonological literature on Alemannic dialects and Markedness Theory in several ways. First, we show that /n/ assimilates to stops throughout Alemannic, with broader distribution than that of Standard German, including distance assimilation across vowels. While there is some variation in how prevalent NPA is within Alemannic, it is a consistent feature in each of the dialects investigated here. Second, we discuss the Alemannic preference for eliminating word-final /n/, although the extent to which /n/ is deleted varies according to region (see Table 3 and discussion in Sect. 4). We argue that deletion of /n/ is precipitated by principles of markedness, specifically preference for unmarked syllable structure (i.e., open syllables). Third, we provide an example of a language that, contra de Lacy (2006, 103), has an epenthetic nasal in onset position (which does not receive [+nasal] from an adjacent segment). We further show that [n] is an ideal candidate for epenthesis, as it is both a coronal and a phonetic stop (produced with an open velum). That is, [n] is unmarked relative to other places and manners of articulation. Our analysis, which considers both the Preservation of the Marked (NPA), as well as Markedness Reduction (n-Deletion and n-Epenthesis), accounts for why these diverse processes interact with /n/ throughout Alemannic. Importantly, our paper provides an example of one language in which one segment undergoes all three processes (assimilation, deletion, epenthesis); while many scholars have argued for the unmarkedness of [t] because it undergoes assimilations, deletions, and epenthesis in different languages, we are unaware of an example of a language in which [t] undergoes all three.

Notes

Data presented in square brackets ‘[ ]’ are standardized according to the conventions of the International Phonetic Association (1999); otherwise, data are presented as they appear in the source material; i.e. the original symbols of the authors who recorded the dialects. One exception to this is that Wipf (1910) transcribes nasalization with a diacritic ‘˱’ under the sound; we transcribe nasalization in citing her work with ‘\( \sim \)’ over a vowel).

Hall’s (2020) article in the Cambridge Handbook of Historical Linguistics is an example of a recent phonological work which, for the sake of clarity and description, does not address phonological theory formally. We leave the question of how to account for /n/-unmarkedness in Alemannic formally to future research.

A fourth change, not discussed in detail here, is the vocalization of /n/ before a fricative in many varieties of Alemannic, as in föif ‘five’ and Fäischter ‘window’ (German fünf, Fenster, Keller 1961, 52). For sake of brevity, discussion of vocalization is subsumed under ‘deletion’ in Sect. 4, though our analysis does not rely on this subsumption.

For a precise depiction of the isoglosses of this bell-shaped Sprachschranke, consult Nübling and Schrambke (2004), maps 1, 2, and 3a.

One commonly cited exception, Imker ‘beekeeper’ (Wiese 1996, 218), is of uncertain origin other than being related to Imme ‘bee’. The -ker suffix could be vocational or an etymological compound which is no longer analyzed as such in the synchronic grammar.

We are aware of no German dialects lacking a process of NPA. In many Alemannic dialects, Place Assimilation affects coronal consonants generally, and not a coronal nasal specifically. For example, Nübling and Schrambke (2004, 300) describe ‘consonant harmony’, whereby a word-final coronal segment assimilates to a labial word-initial consonant. Caro Reina (2019, 279) shows that word-final [d̥] underwent assimilation and later deletion before noncoronal onsets, but assimilation without deletion before nasals. For the purposes of this article, we are narrowing discussion to the coronal nasal in this section and not including further discussion of assimilation of other coronal consonants; see Sect. 6 for comparison of the behaviors of [n] with other coronal consonants in these dialects.

The other Highest Alemannic dialect discussed in this paper also shows consistent NPA. Winteler (1876, 134) describes in detail how an underlying /n/ surfaces as an [m] before the labials [b p f] and as [ŋ] before the dorsal consonants [g k x]. In this dialect, /n/ also assimilates to labial [m] before [m].

Most datasets are presented in the following fashion: the first column is the original author’s transcription, the second column is a Modern Standard German transliteration in italics, followed by an English translation in the third column, and page number in the original source in the fourth column, where applicable.

This morpheme has a fourth realization [fɑ], which surfaces in all other contexts, such as before a sibilant or nasal, as in the phrases [fɑ sīdu] von Seide ‘from silk’ and [fɑ merweits] von Mais ‘from corn’ (Wipf 1910, 113). See Noelliste (2023) for more data and discussion of NPA in Visperterminen.

Baumgartner (1922) gives examples of NPA which exceed the context for the other data discussed here. Specifically, the author gives examples such as [bıns] Binse ‘bulrush’ and [müŋx] Wallach ‘gelding’ (Baumgartner 1922, 123), where the coronal nasal assimilates the place of a following fricative (i.e., the trigger of assimilation is not a stop segment). We see this as an example of how pervasive NPA is in the Alemannic dialect region, such that in Bernese Seeland it extends beyond the context of NPA in other discrete dialects. We leave further analysis of these examples open to future research.

In this instance, the stop which triggers NPA is a nasal. As nasals and plosives are generally considered to be [-continuant], in the sense that there is a complete occlusion of the vocal tract, we see this example as falling under the generalization of nasal-stop cluster.

Noelliste (2017) cites examples of Progressive NPA similar to Standard German for the Bavarian German dialect spoken in Ramsau, Austria. She shows that the coronal nasal infinitive marker assimilates place to preceding stem-final stops and fricatives; however, when the stem-final stop is voiced in this dialect, that voiced stop deletes after assimilation, producing an example like [ɡem] for geben ‘to give’ (Noelliste 2017, 102).

Hall (2020, 12) makes the exceptional behavior of coronals explicit for Standard German as well: before noncoronal stops, the contrast between nasals is generally neutralized, but any nasal can occur before coronal stops.

A historical change relevant to n-Deletion is das Staub’sche Gesetz, ‘Staub’s Law’, named after Swiss dialectologist Friedrich Staub, who first wrote about it in the late 19th century (Staub 1874). Staub’sches Gesetz postulates that an [n] is vocalized before fricatives, compensatorily lengthening the preceding vowel or becoming a vocalic offglide (Werlen 1977). From a comparative standpoint, the process called Staub’sches Gesetz resembles nasal loss before fricatives in historical Germanic, both in the Common Germanic stage (Fulk 2018, 55) as well as later in North Sea Germanic (Prokosch 1939, 86–7; Schirmunski 1962, 381; Fulk 2018, 70). Staub’sches Gesetz is therefore a historical example of n-Deletion in a specific context: before fricatives; Christen (2019, 256–7) describes it as “the nasal spirant law” (das Nasal-Spirant-Gesetz). This historical process has parallels elsewhere in Germanic and in many other language families. Nasal loss before fricatives seems to be articulatorily conditioned: See Ohala and Ohala (1993) for an articulatory phonetic analysis of the incompatibility of buccal obstruents with velic aperture; Ohala and Busà (1995) for a comparative approach documenting similar processes in English, Italian, Western Ossetic, Eastern Ojibwa, Chilean Spanish, Ila, Old Irish, Ciyao, Swahili, Delaware, and Piedmontese; and DeLisi (2021) for an analysis of the historical loss of nasals before anterior fricatives in Latin.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this fact to our attention.

Winteler uses the symbol ‘&’ to represent a low front vowel (Winteler 1876, 92).

A similar process in Dutch is described in Hall (2020, 26). However, in Dutch this change can only occur after schwa.

The exact numbers for n-Deletion in stressed syllables are as follows. Wein: 77% obligatory, 15% variable, 8% no deletion; bin: 60% obligatory, 23% variable, 17% no deletion; Mann: 54% obligatory, 26% variable, 20% no deletion; neun: 70% obligatory, 13% variable, 17% no deletion. (Streck 2012, 195).

A reviewer points out that the feature [nasal] is still present on the output. We interpret this as nasalization accompanied by segmental deletion (rather than coalescence). See Sect. 5 for the distinction between underlying n and Linking-n. Notably, Linking-n does not trigger nasalization.

Kauffmann attributes the presence of [m] in examples such as those in (15a) as being the product of analogical restoration following earlier deletion. It is possible that paradigm leveling can account for this, but the preference to level paradigms with a labial nasal but not those with a coronal nasal would merely underscore the special status of the coronal nasal. Therefore, his historical analysis, which is distinct from our synchronic analysis, may still indicate that markedness is playing a role, as [m] is more marked than [n].

Recall from Sect. 3 that the place feature of a stop is shared with a preceding nasal. Therefore, it is possible that pre-stop nasals are underlyingly unspecified for place, meaning that a velar nasal is not deleting, but merely a placeless nasal. For example, in a word like Bank ‘bench’, when Kauffmann notes (Kauffmann 1890, 161) that it is pronounced [

], it may be that the underlying representation is /

], it may be that the underlying representation is / / rather than /

/ rather than / /, where /N/ is placeless. Thus, the deletion of the nasal would not be a case of velar nasal deletion. Such an analysis would further strengthen the case that coronal nasals enjoy a special status in Alemannic dialects.

/, where /N/ is placeless. Thus, the deletion of the nasal would not be a case of velar nasal deletion. Such an analysis would further strengthen the case that coronal nasals enjoy a special status in Alemannic dialects.Wipf (1910, §180) mentions the historical deletion of the velar nasal before <g> in words like [