Abstract

This paper discusses analogy as a source of total reduplication in Gizey (Masa < Chadic < Afroasiatic). Building on the Dual Theory of reduplication, I first argue that CV- reduplication in the Masa branch of Chadic is a phonological duplication substituting for the segmental material of a now obsolete prefix (*mV-). I then show that a considerable number of total reduplicatives in Gizey derive from analogical reduplication (morphological doubling) entailing the shift from Proto-Masa *CV- reduplication to total reduplication (*CV- reduplication > TOTAL reduplication). The target sublexicon triggering this analogical shift consists of pre-existing ideophonic/onomatopoeic total reduplicatives. The lexical material examined in this paper is composed mainly of frozen reduplicatives i.e., word forms built by duplicating unattested bases. I show that these vestigial reduplicatives also allow for positing two other morphological doubling processes where specific cophonologies truncate specified phonological material. I also consider potential challenges dealing with infixal reduplication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

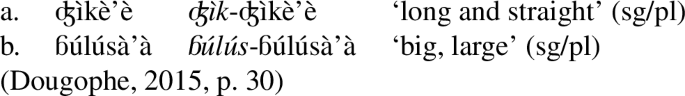

Reduplication can generally be described as consisting in ‘the doubling of some component of a morphological base for some morphological purpose’ (Inkelas & Downing, 2015a, p. 502). Form similarity with a base and morphological increment are therefore two essential characteristics of this process. In many contemporary Chadic languages, reduplication is a common productive process for deriving new words and encoding various morphosyntactic categories (Allison, 2012; Dougophe, 2015; Frajzyngier, 2002; Newman, 2000; Schuh, 1998; Viljoen, 2013). In Mafa (ISO 639-3: maf, Biu-Mandara), for example, partial reduplication is used to derive adjectives from nouns.

-

(1)

Still in Mafa, partial reduplication inflects plural number on adjectives or marks corrective verb focus.

-

(2)

-

(3)

Mbara, another Biu-Mandara language (ISO 639-3: mpk) spoken in Chad, uses -VːCVFootnote 1 reduplication to mark nominal and adjectival plurality (Tourneux, 1986).

-

(4)

The Chadic family consists of four branches: West Chadic, Biu-Mandara, Masa, and East Chadic. With the notable exception of Hausa (West Chadic), Chadic languages are often drastically under-researched and under-documented. Reduplication is one of the most researched topics in individual Chadic languages (see Al-Hassan, 1998), but still, our understanding of its nature in Proto-Chadic and in present-day Chadic languages remains fragmentary.

The evolution of reduplication in present-day languages does appear to be puzzling. A particularly relevant issue, to be addressed in this paper, is the fact that some languages have not maintained it as an active morphological process. This is the case of many Masa languages. In this paper, I will particularly focus on one Masa language, Gizey. Gizey contains only a few frozen reduplicatives (probably inherited from Proto-Masa) in the noun, ideophone, and interjection classes. Yet, restricted as it is, this set of frozen reduplicative makes available interesting hypotheses about the status of reduplication in Proto-Masa and morphological changes undergone by Gizey.

The term frozen reduplication refers to word forms that ‘phonologically have a reduplicated structure, but which from a synchronic point of view constitute essentially unanalysable simple lexical items’ (Newman, 2000, p. 509). Frozen reduplication is commonplace in Chadic. Even languages that have maintained reduplication as an active morphological process still contain such vestigial forms. This is the case for example of Hausa (ISO 639-3: hau) as shown in (5). The asterisked forms are the unattested bases from which the words bâlbēla⌝, kaŋkanā, gaggāfā, and ƙōƙìƙōƙì are derived.

-

(5)

Frozen reduplication is not limited to Chadic. Novotna (2000) reports cases in Swahili (ISO 639-3: swa, Bantu) which she has labelled “pseudo-reduplication”.

-

(6)

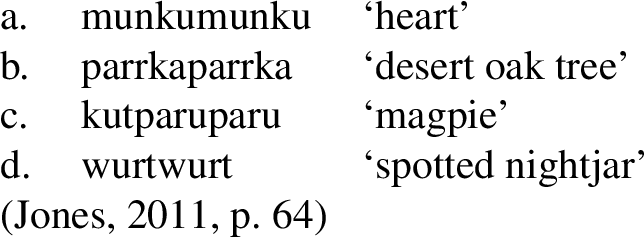

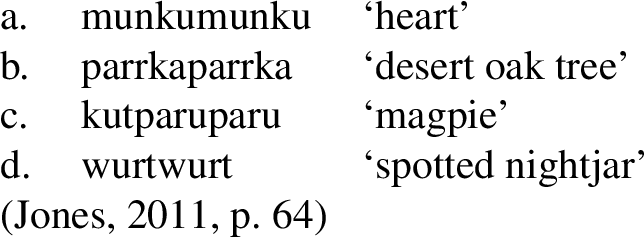

Jones (2011) has also described frozen reduplication in Wangkajunga (ISO 639-3: mpj), a Pama-Nyungan language spoken in north-western Australia.

-

(7)

Finally, Bakker (1987), as cited by Gooden (2003), reports the following examples of ‘morphologically frozen’ reduplicatives in the Suriname creole Sranan (ISO 639-3: srn).

-

(8)

The traditional observation about frozen reduplicatives, which also transpires from the data presented from (5) to (8), is that cross-linguistically, such forms tend to overwhelmingly denote fauna and flora. However, apart from this run-of-the-mill observation, descriptions of frozen reduplicatives generally overlook what these can reveal about the formal and functional properties of reduplication in earlier historical stages of the investigated languages.Footnote 2 Instead, one usually encounters conclusions like ‘…it is almost impossible to establish a certain pattern which would clarify the nature of the lexical items concerned’ (Novotna, 2000, p. 66) or ‘… it is difficult to say what its meaning(s) may have been’ (Viljoen, 2013, p. 119).

While it does prove quite difficult to establish the semantic content of the uninflected unattested bases (especially for languages with limited written tradition), frozen reduplicatives constitute very useful archaeological material for historical studies. Frozen reduplicatives are key traces of hitherto active phonological and morphological processes which may have an important bearing on synchronic morpho-phonological happenings. Newman (1989), for example, has used frozen forms to propose a historical change from suffixal to prefixal reduplication without which the description of present-day Hausa pluractionals would have been challenging. Following this trend, in this paper I will rely on a residual set of frozen reduplicatives to construct an image of reduplication in Proto-Masa.

The analyses I present can be couched within the Dual Theory of reduplication (Inkelas, 2008; Inkelas & Zoll, 2005), which offers a transparent and intuitive way to conceptualise the reduplicative phenomena to be presented. The Dual Theory of reduplication posits a clear distinction between phonological duplication which is triggered by phonological constraints or rules, and morphologically driven doubling. Both sources of reduplication manifest in the data under scrutiny here. I will analyse *CV- reduplication in Masa as a phonological duplication, which substitutes the segmental material (via assimilation) of the Afroasiatic prefix *mV- (Meyer & Wolff, 2019). I then show that a number of frozen total reduplicatives in Gizey derive from a shift from Proto-Masa *CV- reduplication to total reduplication. This morphologically mandated shift is driven by analogy with a morphological niche constituted by pre-existing total reduplicatives (generally of ideophonic or onomatopoeic origin). I also discuss examples of morphological doubling pertaining to partial reduplication. I will invoke the Morphological Doubling Theory (Inkelas & Zoll, 2005) to analyse -CVC and CVC- partial reduplications as instances of double insertions of roots with further truncation of one of the duples (Inkelas, 2008; Inkelas & Downing, 2015b; Inkelas & Zoll, 2005; Steriade, 1988). Generally, this paper adopts a constructional approach, especially as laid out within Sign-Based Morphology (Orgun, 1996). Accordingly, specific phonological functions, cophonologies (Inkelas, 2008; Inkelas & Zoll, 2005; Orgun, 1996), active at different levels (mother or daughter nodes) will handle the phonological duplication relating to *CV- reduplication, as well as truncation in the morphological doubling cases.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Sect. 2 provides some background information on Gizey along with some distributional information about total and partial frozen reduplication. Section 3 discusses the analogical change from *CV- reduplication to total reduplication in Gizey. This analysis raises questions tackled in Sect. 4 which describes *CV- reduplication in Masa as phonological duplication. I will round up my analysis of total (frozen) reduplication in Gizey by explaining why vowel deletions occur in frozen total reduplicatives, in Sect. 5. Sections 6, 7 and 8 are devoted to frozen partial reduplicatives. In Sect. 6 I will argue that the -CVC formative encodes length, straightness, and large quantity (morphological doubling). In Sect. 7, I discuss the infixal -CV- reduplication and highlight analytical challenges posed by infixal reduplication. In Sect. 8, I discuss a CVC- partial reduplication pattern which begs for a treatment as morphological doubling.

2 Some notes on Gizey

Gizey is spoken in a territory of 120 km2 across North-Eastern Cameroon and South-Western Chad (Gaffuri & Melis, 2018). This territory (Fig. 1) is at the east side of Lake Fianga which acts as a natural border between the Gizeys and the Winas. The Winas (who live in the eponym sub-division in Cameroon) speak a variety of Gizey which shows signs of contact with Tupuri (Adamawa, Niger-Congo).

Geographic location of Gizey (D’Ascenzo, 2019)

Previous studies on Gizey include De Dominicis (2006a, 2006b, & 2008), Ajello (2007 & 2011), Ajello and Melis (2008), Gaffuri and Melis (2018), and Gaffuri et al. (2019). These studies either fall within a) a descriptive programme which has mainly sought to describe the unique linguistic and cultural features of Gizey and its speakers or b) a comparative programme whose aim has been to compare Gizey and Masana (ISO 639-3: mcn) with the view to telling whether both constitute the same or distinct languages (see Gaffuri et al., 2019). Gizey has been described as a dialect of Masana (Barreteau & Dieu, 2005). However, Melis (2019) has convincingly argued against this classification, and Gizey appears as a distinct Masa language in Newman’s (2013) classification.

-

(9)

Most of the data presented for Gizey in this paper were collected by Antonino Melis and have been published in Ajello and Melis (2008) and Ajello et al. (2001). The latter publication provides comparative data with almost 1400 lexical entries from Musey, Marba, Masana, as well as Lew and Ham, the two other Northern Masa languoids not included in Newman’s classification (Ajello & Melis, 2008). Additional data are taken respectively from Roberts and Soulokadi (2019) and Shryock (n.d.) for Musey (ISO 639-3: mse) and Melis (2006a) and Melis (2006b) for Marba (ISO 639-3: mpg) and Masana, respectively. The Zime (ISO 639-3: zim) data cited below come from Vincent’s (2000) online database on this Southern Masa language. More than 700 frozen reduplicatives in total were manually extracted from these sources.

Gizey is an SVO language with no case marking. TAM load is shared between lexical verbs, auxiliary verbs (grammaticalized verbs), and verbal particles. Tone may mark aspect (perfective vs. imperfective), mood (imperative) and nominalization. There has been a morphologization in the verb class of the consonant-tone interaction, so that verbs distribute between a high and a low class depending on initial consonant quality (Melis, 2019). Most words in Gizey are either monosyllabic (50%) or disyllabic (40%) and empty onsets are disallowed in word initial position. Words with longer syllabic constitution (usually above four syllables) involve (frozen) reduplication or compounding.

Table 1 summarises attested word structures in the four main lexical classes in Gizey namely nouns, verbs, adverbs and ideophones.

Compounding is also widely used in Gizey and Masa in general for the formation of nouns denoting fauna and flora. Compounds can be exocentric (10a-c) or endocentric (10d).

-

(10)

Affixation is limited in Gizey. The only bound morphemes which can be analysed as genuine suffixes are the plural markers -íj, and -Vj. Other bound morphemes like the definite article (=na/=ta) or the ventive particle =Vj are clitics.Footnote 3

In Gizey, almost 1 in 4 words denoting fauna and flora involves frozen reduplication and close to 63% of the word forms with frozen reduplication refer to objects in the fauna and flora domains. Remaining frozen reduplicatives refer to emotions, body parts and bodily sensations etc.

Frozen reduplication mainly occurs in nouns and ideophones. There is also a set of ‘affective’ frozen reduplicatives including expressive and conative interjections (Ameka, 1992) and emotionally charged appellations emerging probably from child language.

-

(11)

However, be it in the major classes (nouns and ideophones) or in interjections, frozen reduplication appears as a rather marginal phenomenon. In the class of ideophones, only about 13 frozen reduplicatives could be extracted from a total of 362 ideophones in my working data set. In the noun class, I identified about 127 frozen reduplicatives out of 1467 noun entries. This is not surprising given that these words are mainly remnants of a now obsolete process. This limitation could also be explained in part by the fact that most words in Gizey are monosyllabic, as seen above.

From a purely formal perspective, frozen reduplication is largely continuous and total (80%). Frozen reduplicatives in which only a clearly identified subpart is doubled (partial reduplication) constitute only 20% of the Gizey data consulted for this paper.

3 Analogical change from *CV- to total reduplication

In this section, I am going to present data from Masa which allow reconstructing a *CV- reduplicative formative for Proto-Masa. I will also provide data showing that many word forms using this formative correspond to total reduplication in Gizey. I will then propose that the corresponding frozen reduplicatives in Gizey result from an analogical change targeting a morphological niche consisting of pre-existing total reduplicatives.

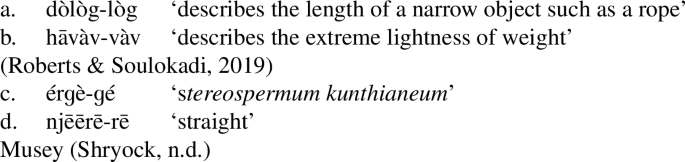

The CV- formative is widespread in Masa, as can be seen from these data from Musey (12) and Marba (13) in the Northern Masa branch and Zime (14) in the Southern branch.

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

Table 2 provides a few cognates from the Northern Masa sub-branch from which three main observations can be made: a) Musey, Lew and MarbaFootnote 4 overwhelmingly use a CV- reduplicative formative which is not attested in Gizey and appears only scarcely in Masana and Ham, b) word forms with the CV- formative in Musey-Marba-Lew correspond to total reduplication in Gizey-Masana-Ham (e.g. ‘asparagus P.G’); and c) not all words with the CV- formative in Musey-Marba-Lew match with total reduplication in the other languages (e.g. ‘rousettus’).

It appears from these data that the CV- formative can suitably be reconstructed as *CV- in Proto-Masa given that it is widely attested across cognates. If this is the case, then morphological change can be evoked to account for the correspondence between total reduplication in Gizey and *CV- reduplication in the other languages.

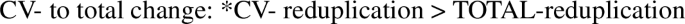

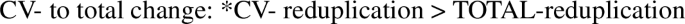

There are two ways to account for this morphological change: either total reduplication is the innovation and partial CV- reduplication the conservative structure or vice versa. The directionality explored here is CV-reduplication > total-reduplication i.e., CV reduplication is the conservative structure and total reduplication the innovation. Thus, I submit that Gizey has undergone a diachronic change targeting the shift of some CV- frozen reduplicatives (CV-reduplication) to total reduplication. This morphological change is formulated in (15) and exemplified in (16). As I will show in the next section, this analysis offers a number of descriptive advantages which seem difficult to achieve the other way round.

-

(15)

-

(16)

One must now describe the triggering mechanism underlying the shift in (15). I suggest that (15) developed from analogy with an existing morphological niche composed of total frozen reduplicatives of onomatopoeic and ideophonic origin. The term morphological niche is adapted from the concept of semantic niche (Cetnarowska, 2020), which refers to ‘groups of words (subsets of a morphological category) kept together by formal and semantic criteria and extensible through analogy’ (Hüning, 2009, p. 181). Given that the binding criterion is more formal than semantic in the data under study, the adjective morphological is preferred to semantic.

The morphological niche which triggers the analogical (total) reduplication in Gizey (and probably in Masana and Ham) consists of total frozen reduplicatives which either correspond to total frozen reduplicatives in sister languages or forms unique to Gizey. As such, they cannot be analysed as deriving from the application of (15). These include words like those in (11) repeated as (17) below or ideophonic/onomatopoeic forms like those in (18) and (19).

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

It is easily seen that there is no other unifying trait, apart from morphological doubling which binds the words under (17)–(19) into a single class. (This is why I prefer the label morphological over semantic niche.) Total reduplicatives forming this morphological niche account for about 78% of the 115 total frozen reduplicatives in my Gizey dataset, while those derivable from (15) represent about 22% (these figures represent type frequency, not tokens). Analogical change thus appears to be used as a regulatory process whose aim is to reduce the size imbalance between the two subsets by directing the minority set towards the dominant morphological niche (model).

Concretely, the transformation of CV-reduplicatives is resolved by copying the model of members of the morphological niche as shown in (20).

-

(20)

The analysis in (20) lends support to Hüning’s (2009) observation that ‘new words are coined not according to an abstract word formation rule, but according to the model of one or more existing words’ (p. 185). The exact details of this change are discussed in the following section.

4 The emergence of CV- reduplication in Masa

One issue I purposefully left outstanding in the previous section, but to which I return now is the status of the Proto-Masa *CV- formation. The question is whether *CV- reduplication is phonological duplication or morphological doubling. This issue is addressed in 4.1. In 4.2 I discuss the diachronic stages leading to total reduplication in Gizey.

4.1 *CV- reduplication is phonological duplication

In Musey and Marba, the CV- formative is mainly encountered in terms denoting birds and insects, as well as other animals. In general, the likelihood of having words with the CV- formative referring to fauna or flora is very high in all the languages examined. In the Marba data for example, about 50% (out of 114) of the forms using this formative refer to animals or plants. This percentage is even higher if one also counts words referring to objects and activities associated with animals and plants. Clearly, the CV- formative behaves like a kind of prefix used primarily for nouns denoting fauna and flora and which might have been extended to other semantic domains related to human activity and conditions.

The grouping of nouns denoting animals, body parts, body sensations etc. by *CV- reduplication in Proto-Masa is quite reminiscent of the Afroasiatic prefix *m(V)- (Meyer & Wolff, 2019), whose reflexes in Chadic ma-/mu-/mə- are known to occur with such a classifying use (Barreteau, 1978; Frajzyngier et al., 2011; Schuh, 2008 etc.). In Mofo-Gudur for example, mà- occurs as a derivational morpheme in a considerable proportion of nouns including agentives, toponyms, and nouns denoting plants, animals, body parts and conditions, etc. (Barreteau, 1978), as illustrated in (21).

-

(21)

A few words with the *mV- formative can also be found in the Marba-Lew continuum. Table 3 provides word forms from Marba-Lew containing this formative and corresponding forms in Gizey.

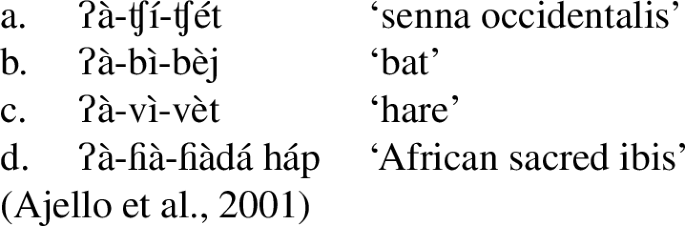

Interestingly, the Marba-Lew continuum also consistently prefixes ʔà- before nouns denoting fauna, flora, celestial bodies etc.

-

(22)

The presence of the prefixes ʔà- and *mV- in Marba and elsewhere in Chadic might suggests that CV- reduplication can be conceived of as a kind of phonological (reduplicative) surrogate for either of these prefixes. This is particularly so as CV- reduplication on the one hand and ʔà- and *mV- on the other hand seem to have the same function (that of grouping words denoting fauna, flora, human activities, and body conditions). Examples such as the ones in Table 4 may suggest that CV- reduplication relates specifically to ʔà-. However, word forms with ʔà- in Marba do not generally correspond to CV- reduplication in the other languages (e.g., Marba: ʔà-jùm ‘honey’ vs. Gizey: júm).

Furthermore, Marba-Lew contains many frozen reduplicatives in which CV- reduplication co-occurs with ʔà- as exemplified in (23). This further shows that CV- reduplication is different and not specifically related to ʔà-.

-

(23)

As just argued, Marba-Lew data strongly suggest that *CV- reduplication is not specifically related to ʔà-. It is likely, nonetheless, that this formative also comes from a corresponding preposed CV- morpheme in Chadic or Afroasiatic—and *mV- is available for this role. A reasonable assumption, then, is that *CV- reduplication either derives from compensatory reduplication (see Yu, 2005), which ensures that the remnant templatic material of *mV- is properly filled, or results from an assimilatory process. It is this second (more economical) option that I will be exploring in the next paragraphs, namely that *CV- reduplication derives from an assimilatory process mandated by Proto-Masa phonology. This solution seems more frugal than the one introducing segmental impoverishment (deletion of the segmental material of *mV-) and subsequent slot filling. Either way, what is important is that the facts shown here involve phonological duplication, and not morphological doubling.

The data in (23) suggest that the emergence of ʔà- in that continuum is subsequent to that of *CV- reduplication. This assumption is necessary to explain why ʔà- and *CV- reduplication cooccur in forms like (23). What is intriguing about this prefix is its suspicious absence from other languages of the Masa branch, while it is found across Central Chadic as aFootnote 5 – (Colombel, 2005; Tourneux, 1978). Thus, either Marba retains this prefix from an early developmental stage which also includes the Central Chadic languages, or it has imported it (borrowing) from a neighbouring language. If Marba retains this prefix from an early diachronic stage, then Proto-Masa word forms containing it might have undergone morphological changes like those affecting CV- reduplicatives. Correspondence between Marba words containing ʔà- and words with either total reduplication or just the base input (without ʔà-) would seem to confirm this idea.Footnote 6 Thus, words like those under Table 4 strongly suggest that this process which initially, probably affected only *mV- forms was (is?) also extended to word forms containing ʔà-.

Assuming that the diachronic change discussed under this section proceeds from CV- to total reduplication (and not from total reduplication to CV-reduplication) offers three distinct advantages. First, it allows for linking Proto-Masa CV- reduplication with Proto-Chadic and Afro-Asiatic *mV-, especially as both formatives clearly share some semantic and phonological features. In fact, with this analysis, CV- reduplication becomes an available trace of the *mV- formative in Masa, where its absence otherwise would have been highly suspicious. Secondly, it is possible to identify a strong source for the observed change: a dominant morphological niche (underived pre-existing total reduplicatives) forces an analogical shift of a minority niche (inherited frozen CV- reduplicatives). The reverse situation is less plausible given that a potential CV- reduplication niche in Marba, Musey, and Lew seems too small to be able to trigger this change. Third, it would be extremely difficult to account for the morphological/semantic content of the underived source total reduplicatives if one were to consider CV- reduplication as the innovation. If total reduplication were the conservative structure, the only plausible source for morphological doubling should be symbolism (given the variety of the senses expressed by total frozen reduplicatives). And yet, there are very few total frozen reduplicatives for which a convincing sound symbolic interpretation could be posited. For example, how would one account for the reduplication in ɦùlómɦùlóm ‘asparagus P.G.’ given that its sound symbolism is not immediately obvious and that it does not seem to encode any grammatical information? All that being said, I do lack the necessary comparative data to fully rule the alternative analysis out, especially given the sparse nature of Chadic diachronic data. To definitely settle this issue, it would be very interesting to find data showing regular correspondence between *mV- forms in Proto-Chadic and their CV- reduplicative cognates in Masa.

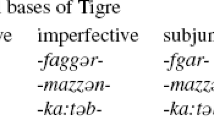

4.2 Diachronic stages from *mV- to total reduplication

In line with hypotheses outlined in the foregoing, I am now in position to present the details of the proposed diachronic stages from Proto-Chadic *mV- to total reduplication in Gizey. Events begin in Proto-Chadic where *mV- (inherited from Afro-Asiatic) is used as a productive nominalizing prefix. This is the most likely explanation for why it is still attested and productive in some contemporary Chadic languagesFootnote 7 (Schuh, 2017). Proto-Chadic nominalization with *mV- could be modelled with the schema in (24a), which is an implementation of realizational morphology (Anderson, 1992; Stump, 2001) within Sign-Based Morphology, with specific cophonologies handling the realization of affixes as well as the phonology processes associated with them (Inkelas & Zoll, 2005; Orgun, 1996). (24b) provides a concrete illustration with the Ngizim agentive maruwái ‘farmer’ from Schuh (2017, p. 535). In these schemata, the phonological function \(\varphi_{\mathrm{c}}\) prefixes the derivational morpheme *mV- and specifies the surface form of the mother node. Syn stands for syntax (specifies grammatical class), Sem for semantics (specifies meaning), and Phon for phonology (specifies the phonological form); a, loc, ins stand for ‘agent’, ‘location’, and ‘instrument’, respectively. These represent the range of senses the construction under (24a) can denote. In (24b), ‘agent of ru⌝yu’ is one instantiation of the semantics of this construction.

-

(24)

In Proto-Masa then, the change from *mV- to CV- reduplication is linked to the emergence of a new cophonology (expressed as \(\varphi_{\mathrm{v}}\) in (25) below) targeting the copy (via assimilation) of C1 and V1 segments of the input daughter nodes. The effects of this new phonological function are represented with the Zime word for ‘kori bustard’, pu-puk (Vincent, 2000).

-

(25)

At this stage, a morphological doubling operation in Gizey (and probably in Masana and Ham) takes Proto-Masa CV-reduplicatives as input and transforms them into total reduplicatives under analogy with the morphological niche discussed in Sect. 3. Concretely, input CV- reduplicatives are inserted twice i.e., for a form like *ɦùhùlóm ‘asparagus P.G.’ the morphology doubles its phonological material. Then, daughter node cophonologies truncate the initial CV material before this input is concatenated by mother node cophonology. The construction yielding the attested outputs is given in (26) and illustrated in (27). Note that the phonological and morphological operations affecting nodez does not trigger any meaning change. This is materialised in the schema under (26) by repeating \(\mathrm{Sem}_{y}\).

-

(26)

-

(27)

A crucial question at this point is whether the morphological process underlying the doubling of heretofore CV-reduplicatives has access to information that the copied CV- has a different status than the input base i.e., that, for example in *ɦù-ɦùlóm ‘asparagus P.G.’, ɦù- (CV- formative) has a different morphological status from *ɦùlóm. This may explain why that CV- material is clipped in the first place while only the base material is maintained (with an instruction like ‘delete CV-prefix’). The way Sign-Based Morphology solves this apparent challenge to the Bracketing Erasure Convention (Pesetsky, 1979) is by including the Relativized Opacity Theorem (Orgun & Inkelas, 2002) in its architecture and by referring directly to lexical types (Orgun & Inkelas, 2002). The Relativized Opacity Theorem is stated in (28) below. As for lexical types, they refer broadly to specific sublexica with words sharing morphosyntactic and semantic features.

-

(28)

-

a)

The grammar can access information regarding the presence of an affix or construction in a daughter node, as long as that construction is the top node in the daughter node’s constituent structure.

-

b)

The grammar cannot access any morpheme boundary information within a daughter node – not even boundaries associated with constructions whose presence is known from clause (a).

Accordingly, the morphological doubling process responsible for the reduplication could be interpreted as making specific reference to a lexical/construction type (e.g., one labelled as *CV-reduplicative nouns and composing of CV-reduplicatives inherited from Proto-Masa). This rule could be framed as: DOUBLE INSERT *CV-REDUPLICATIVE NOUNS. And so, only information regarding the presence of the CV- prefix is accessed by the morphology, and not information concerning internal boundaries in line with the Relativized Opacity Theorem. As for the clipping instructed by the \(\varphi_{\mathrm{b}} \) cophonology, it can simply be conceived of as deriving from the need to satisfy an independent phonological or aesthetic constraint (whose exact nature however needs to be defined) which does not require access to internal boundaries. Note that the effects of the \(\varphi_{\mathrm{v}} \) cophonology, which is responsible for assimilation have been reported elsewhere in Chadic. Gravina (2014), for example, has shown that CV segmental material not retained from Proto-Mofu is substituted by root segmental material through compensatory reduplication; this is illustrated in Table 5. This constitutes serious evidence on the existence of this process within Chadic.

A last clarification is in order before moving to the next section. The analysis just made presupposes that two constructions were probably competing. One of these constructions is involved in the analogical reduplication. The other one, which accounts for the facts under Table 6, involved the clipping of the CV- material of CV- reduplicatives. This explains why we find words like those in Table 6 which also correspond to CV- reduplication in the other languages. The co-existence of these two constructions reinforces the idea that the morphological processes underlying them refer to a specific construction type (CV- reduplicatives) which is the input of either the clipping construction or the doubling construction.

5 Phonological changes in total frozen reduplicatives in Gizey

Now that the diachronic origin of total frozen reduplicatives in Gizey has been set out, it is time to turn to the main phonological process affecting these forms: the deletion of the second vowel in CV.CV-CV.CV words. I will argue that this deletion process can be analysed as hiatus resolution arising from a prior application of metathesis (itself fed by reduplication).

Generally, total (frozen) reduplication in Gizey is faithful at segmental and suprasegmental levels, as shown in (29).

-

(29)

Certain total reduplicatives may undergo phonological changes. It is the case of the words in (30) which, from first sight, appear to involve CVC- reduplication. However, independent language internal and crosslinguistic evidence rather indicates that these words have underlying CVCV-CVCV template.

-

(30)

Newman (1986, 2000) has analysed similar forms in Hausa as deriving from full doubling of *CV.CV bases whose final ‘doomed’ vowels are deleted diachronically ([*CV.CV]base-[CV.CV]red > [*CVC]base-[CV.CV]red). However, contrary to this diachronic analysis proposed by Newman for Hausa, the process involved is rather a synchronic one in Gizey.

V2 deletion is a recurrent phonological process in Gizey, generally linked with hiatus resolution. The word forms in (30) can be analysed as resulting from the resolution of hiatuses created by a metathesis rule operating in various collocations with suffixal or enclitic morphemes. The examples in (31) have a plural marker, those in (32) a personal pronoun. The hiatus resolution process is shown in (33) with the derivation of bùngíj ‘guns’ and g ‘your penis’.

‘your penis’.

-

(31)

-

(32)

The surface forms in (31) and (32) can be derived as illustrated in (33) with the derivation of bùngíj ‘guns’ and  ‘your penis’.

‘your penis’.

-

(33)

The same analysis can be applied to the frozen reduplicatives as shown in the following derivation.

-

(34)

To be sure, independent evidence for postulating an underlying second vowel in the forms in (30) can be drawn from comparative data. Cognate forms in sister languages do generally maintain this vowel. Table 7 shows that Masana, Ham and Musey have a surface vowel occurring in the position corresponding to the elided vowel in Gizey. This is clear evidence that the word forms in (30) involve total reduplication, which is then followed in Gizey by the deletion of the second vowel, following the derivation in (34). This deletion could be attributed to mother node cophonologies affecting CVCV-CVCV structures irrespective of their source (reduplications derivable from (15) or not, non-reduplications). The fact that this deletion process affects both reduplicative and non-reduplicative structures conforms to Generalised Phonology Prediction (Inkelas & Zoll, 2005) stated in (35).

-

(35)

The set of phonological effects found applying within reduplication is equivalent to the set of morphologically conditioned phonological effects found outside of reduplication. There is nothing unique about the phonology of reduplication constructions.

There are frozen reduplicatives in Masana whose surface CVC-CVCV structure is similar to that of those in (30), but which result from an independent constraint on the occurrence of consonant clusters. These forms generally have CVC-CVC cognates in sister languages as can be seen from Table 8.

There are usually two ways in which Masana breaks consonant clusters in this context: it either inserts an agreeing vowel in final position, as illustrated above, or inserts [a] between the two consonants. Each of these strategies yields forms that can generally be used as free variants. And while the consonant clusters could also be maintained (as in (36) below), some forms are only attested with an intervening vowel (see (37) below).

-

(36)

-

(37)

Gizey V2 deletion in frozen reduplicatives and in collocations involving suffixes and clitics points to considering total reduplication as affixation rather than self-compounding as is expected within Morphological Doubling Theory (Inkelas & Downing, 2015b). I have shown in (33)-(34) that just like in cases where suffixes or clitics are collocated with disyllabic roots (e.g., (31) and (32)), total reduplication also feeds V2 deletion, while this is not observed with compounding. Following the analysis in (33), one should expect metathesis to occur in compounds like (38), such that the environment for the deletion of /e/ is created. This does not seem to be the case as evidenced by the fact that *bìnn-ùnok is ungrammatical.

-

(38)

At the same time, contrary to affixation, which provokes the raising of root V1 (gòr + -ɛj >  ‘children’; zàl + =am >

‘children’; zàl + =am >  ‘boil it’), compounding and reduplication do not show this metaphony. Thus, concerning V2 deletion, total reduplication behaves like affixation, whereas when it comes to metaphony, total reduplication behaves like compounding. The exact nature of the similarities and difference between reduplication and affixation on the one hand, and reduplication and compounding on the other hand is a topic that needs more in-depth research, as this also touches on what model is more suited for analysing reduplicative phenomena.

‘boil it’), compounding and reduplication do not show this metaphony. Thus, concerning V2 deletion, total reduplication behaves like affixation, whereas when it comes to metaphony, total reduplication behaves like compounding. The exact nature of the similarities and difference between reduplication and affixation on the one hand, and reduplication and compounding on the other hand is a topic that needs more in-depth research, as this also touches on what model is more suited for analysing reduplicative phenomena.

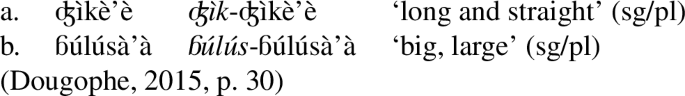

6 Morphological –CVC reduplication

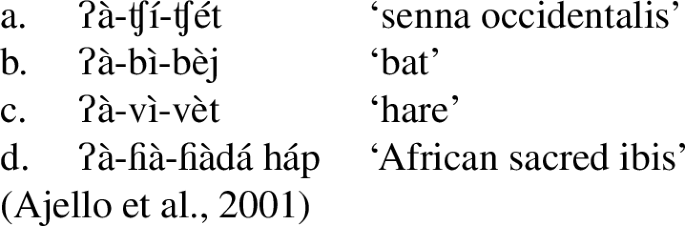

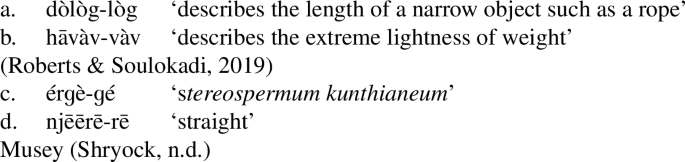

The analysis developed in the foregoing does not apply to another Gizey reduplicative pattern, which consists in doubling the final syllable of unanalysable bases. The –CVC formative is attested in nouns (39) and ideophones (40).

-

(39)

-

(40)

Generally, frozen reduplicatives using this pattern denote length, straightness, large quantity, and intensification. The items in (39) and (40) relate to snakes (e.g., ʧìkíl-kíl ‘elapsoidea guntheri’), large quantity (e.g., tíníŋ-níŋ ‘sense of huge quantity’), straightness (e.g., ɗìgèr-gèr ‘straight’), or length (e.g., lígìw-gìw ‘very long’). Example (40b) is particularly interesting, as it is one of the few cases where the derivational function is apparent. It relates to the verbo-nominal ɗigɛr ‘to make straight’ or ‘righteousness’, from which the ideophone ɗìgèrgèr may have derived. In Zime, the cognate form diker-ker refers to the zenith, whose sense (highest point) intersects with straightness and length. In Gizey, the word ʤùkúl-kúl ‘hoopoe’ is extended to humans with elongated heads from analogy with the spike formed when hoopoes lower their crest.

Given the systematicity occurring with the use of the pattern shown under in (39) and (40), there is no doubt that the duplication process involved was warranted by the morphology in an early diachronic stage (Proto-Masa). Thus, the facts in (39) and (40) must be regarded as morphological doubling. Accordingly, each of the given forms involves double insertion of the unanalysable bases, plus truncation occurring at the rightmost daughter node. The morphological construction underlying -CVC reduplicatives is given under (41) below and illustrated with ʤùkúl-kúl ‘hoopoe’ under (42).

-

(41)

-

(42)

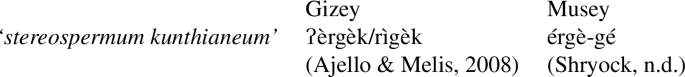

-CVC constructions seem to be a rare in Masa, especially in the Northern sub-branch. Roberts and Soulokadi (2019), for example, have indicated that they are involved in only about 8% of Musey ideophones. One finds almost the same distribution in Gizey. And while truncation in Gizey systematically results in a -CVC final syllable in the mother node, Marba, Zime and Musey also allow for the occurrence of final open -CV syllables as shown respectively from (43) to (45). Note that -CV forms (e.g., Musey njēērē-rē ‘straight’) also conform to the senses expressed by the construction under discussion. There is therefore no reason to have two separate construction types when both outputs (-CV and -CVC forms) encode the same meanings.Footnote 8

-

(43)

-

(44)

-

(45)

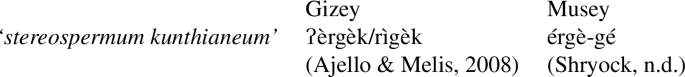

Although open syllables are attested in Gizey, constructions in which truncation keeps only the final CV syllable do not occur. Thus, in order to account for the occurrence of both -CV and -CVC final syllables in the words shown here, it is reasonable to assume that the cophonology at work in (41) deletes everything but the last syllable. The fact that frozen reduplicatives with final -CV syllables do not show up in Gizey could entail that Gizey developed a specific constraint/rule disallowing final -CV syllables in such construction types. Cognate word forms for the stereospermum kunthianeum provide some clues as to how Gizey resolves this issue. Observe in (46) below that the corresponding word form in Gizey does not contain the final vowel seen in the Musey form. It may then be that Gizey further deletes final forms in such constructions.

-

(46)

To sum up, available data suggest that Proto-Masa probably used a doubling construction to encode length, straightness, large quantity, and intensification. This construction is a clear example of morphological doubling in Proto-Masa which differs from the phonological doubling seen with CV- reduplication. The rightmost daughter node in this construction has a distinct cophonology which deletes all base material except for the last syllable. It seems outputs with a final -CV syllable, are disallowed in Gizey where an independent repair strategy (illustrated under (46)) seems to be used.

7 Infixal -CV- reduplication

In this section I will discuss a case of infixal reduplication, -CV-, which probably has phonological bases. I propose somehow tentatively that this reduplicative process involves templatic slot filling. I conclude the section by showing that the data discussed could also be interpreted as morphological doubling.

Infixal frozen reduplication in Gizey involves a -CV- formative whose segmental material comes from the initial CVC- syllable of the disrupted base. Some examples are provided in (47).

-

(47)

Similar forms have been identified in Masana:

-

(48)

Generally, there is no semantic content which emerges from the use of this formative. In Chadic the -CV- formative is not uncommon (see Al-Hassan, 1998, pp. 85–88). In languages in which it is attested with a morphological function, -CV- reduplication generally marks plurality. In Muyang (ISO 639-3: muy), for example, although nominal plurals are rare, a few residual nouns denoting animals and humans encode nominal plurality with the -CV- formative (Newman, 1990). In other languages like Dghweɗe (ISO 639-3: dgh), the -CV- formative is used to encode pluractionality (Frick, 1978).

One possible analysis then is to assume that the non-plural use of -CV- in Gizey and Masa is an exaptation of form without function. In other words, this formative is extended to word forms in which it did not occur initially without transfer of its semantic content. This extension could be modelled in terms of an analogical change under influence of a morphological niche with words which formed their plural with this formative. Form transfer is not an unusual process in reduplication. Cases of reduplication with exaptation have been reported in Chadic. Schuh (2002) has suggested for example that the CVC formative (attested across Chadic) has been recycled in Hausa for pluractionality marking, even though it initially occurred in non-verbal contexts. In Hausa, though, this transfer is followed by the acquisition of a new clearly identifiable function, which does not seem to be the case or is not immediately accessible for -CV- reduplication in Gizey.

To formalise this analysis within Morphological Doubling Theory and Sign-Based Morphology, the word forms under (47) and (48) could be regarded as involving an underspecified infix (-CV-) whole templatic slots are filled via phonological duplication. The schemata under (49) below represent this formalisation. The phonological function \(\varphi_{d} \) introduces the infixal template (just like any other affix) and specifies how it is filled, namely by copying the first and the second segments of the preceding syllable.

-

(49)

The word forms under (47) and (48) could also be analysed as morphological doubling with different cophonologies conspiring to yield the attested output. Still focusing on késkéʤè ‘pycreus’, one could imagine that the morphology calls twice the hypothetical base késʤè which is truncated by the leftmost daughter node cophonology before both insertions are concatenated by the mother node cophonology. The mother node cophonology further deletes a consonant (C4) for some obscure reason. This interpretation is represented in (50).

-

(50)

While both interpretations sound plausible, there is hardly any independent evidence to support them. Also, the limited number of available examples does not allow for making very useful morpho-semantic and phonological generalisations. Finally, on a more theoretical account, the facts shown here also highlight potential challenges in dealing with infixal reduplication. As Inkelas (2014) has pointed out, it is never clear whether one is dealing with phonological duplication or morphological doubling. This observation clearly applies to the infixation data presented here.

8 CVC- (frozen) reduplicatives: morphological doubling

Before concluding, it is important to mention a final (limited) set of frozen reduplicatives in Gizey which I analyse as morphological doubling although the semantic content of the construction is not transparent.

Begin by considering the following word forms.

-

(51)

A number of complications occur when these facts are given a purely phonological account. Firstly, it is not immediately certain whether those forms involve partial doubling or total doubling with additional segmental changes. In purely phonological account, one possible analysis is to consider the forms in (51) to have a preposed CVC- reduplicative formative as shown in (52).

-

(52)

It would then appear that the probing to fill the C2 slot of the CVC-formative is non-linear (antilocal), as the C2 of the hypothetical bases (always /l/ or /r/) is never copied. (Had it been the case, then one would have *kòl-kòlòŋ instead of kòŋ-kòlòŋ.) It would seem there is a constraint on the sequences [r-ʧ], [l-ʧ], and [l-k/g]. In my dataset, there is one occurrence of the sequence [r-ʧ] (ʧìrʧír ‘anacridium wernerllum’), no occurrences of [l-ʧ] and 16 occurrences of [l-k/g] (ʤàlká ‘sole ulcer’, sèlgèt ‘rainbow’). However restricted, two of these sequences appear as licit in Gizey. Note that even if this constraint referred specifically to structures *[CVl.CVl] and *[CVr.CVr], there would still be some counterexamples. The [CVl.CVl]/*_* and [CVr.CVr]/*_* sequences give 10 and 13 hits respectively in my data. A few examples are given in (52).

-

(53)

Another way to interpret the word forms in (51) as phonological duplication is to consider full doubling from a CVC base where the reduplicative formative is –CVCVC. C1 and C3 of this hypothetical formative would be copies of base C1 and C2 respectively. C2 for its part, would be a pre-determined consonant which surfaces unpredictably (at least phonologically) as /l/ or /r/.

-

(54)

While this may resemble what Newman (2000) has analysed as pseudo-reduplication in Hausa, the Hausa pseudo-reduplicant looks less complex than what is shown here. The proposed Hausa formative is a –VCV template; where the C is a copy of the preceding consonant and the vowels are fully specified (Newman, 2000). Also, a –CVCVC formative seems quite improbable since it is absent from cross-linguistic studies of reduplication in Chadic (see Al-Hassan, 1998).

While the phonological solutions explored above seem descriptively adequate, they fail to meet the locality and size characteristics often pertaining to phonological duplication. As Inkelas and Zoll (2005, p. 22) put it ‘[p]honological duplication is proximal, meaning that it targets the closest eligible element’. In the two scenarios shown above, reduplication often involves copying a non-local segment. In the CVC- analysis for example, the final C of the reduplicant corresponds to the last C of the base while there is an intervening C (l or r). Also, phonological copying generally involves a small amount of segmental copy (usually one segment). In the scenarios shown above, copying seems to involve a minimum of three segments.

In my view, these phonological analyses fail to provide a broad picture of the processes that might be in play in the forms under (51). A more insightful approach is to consider them to involve morphological doubling and truncation in line with (55).

-

(55)

Note that this analysis provides a plausible account for why [o] surfaces in (51a) and (51d) instead of the most local and expected [u], as it is this latter vowel which is targeted by truncation.

-

(56)

Interestingly, the suggested bases in such forms have cognates in sister languages or could be found with other semantic content. For example, gùlòŋ refers to backwater or river in Gizey. The word for snail kìŋkìrìŋ occurs freely as kìŋkìrìŋ or kìrìŋ in Masana.

9 Conclusion

In this paper, I discussed reduplicative phenomena in Gizey and related Masa languages paying attention to vestigial reduplicatives i.e., forms involving the doubling, partial or entire, of bases which are not independently attested. My aim has been to provide insights into the active reduplication phenomena which occurred at the time such frozen reduplicatives were formed in Proto-Masa. The most important insight to be gained from this study is that there have been significant morphological changes related to reduplication. The reconstructed Proto-Masa reduplicative formative *CV- has been analysed as emerging from phonological duplication substituting the segmental material of the Afroasiatic prefix *mV- occurring in word forms inherited from an early diachronic stage. I also showed that a later innovation in Gizey, and possibly in Masana and Ham, triggered the shift of *CV- reduplicatives to total reduplication, probably by analogy with a morphological niche consisting of pre-existing ideophonic and onomatopoeic total reduplicatives. Concerning partial reduplicatives, I discussed *-CV(C) as morphological doubling in Proto-Masa indicating length, straightness, large quantity, and intensification. I also discussed infixal -CV- reduplication which lends itself to a phonological duplication or morphological doubling interpretation. Finally, I showed that CVC- reduplicatives showing large size and/or non-local copying are best analysed as morphological doubling with truncation following insights from the Morphological Doubling Theory (Inkelas & Zoll, 2005).

A general observation about the Masa languages studied here is that reduplication does not appear as an active morphological process, whereas it is widely used elsewhere in Chadic, most notably for nominal and verbal plurality. The real incidence the abandonment of morphological reduplication had on the morpho-syntax of present-day Masa languages still needs to be determined; but it does appear to have fed perceptible changes. For example, while pluractional reduplication remains widespread in Chadic, Gizey and Masana mainly rely on syntactic doubling to express durative, habitual, and distributive aspect, which notions generally subsumed under pluractionality. It would be interesting to find out if this reflects a general paradigmatic shift in Masa. Another topic, so far overlooked in the literature, that warrants further research is the status of prefixes in Proto-Masa and in present-day languages.

Finally, it would be very interesting to test how far the effects of the cophonologies discussed in this paper match with the Generalised Phonological Prediction (Inkelas & Zoll, 2005) i.e., verify whether the morphologically conditioned phonological processes discussed under reduplication occur outside reduplication. Given the fact that Proto-Masa grammar is yet to be reconstructed, it would be good to have comparative data from contemporary Masa languages to check for example whether truncation is mandated by their morphologies outside reduplicative constructions.

Data Availability

The frozen reduplicatives described for Gizey and the other Masa languages can be found via this link: https://osf.io/up5v8/?view_only=c037935d91b54847ab8af7fc24279774

Notes

In reconstructions of Proto-Chadic, the -VːCV reduplicative morpheme used in Mbara has been considered, though unavailingly, as a method for encoding nominal plurality (Newman, 1990). While being attested in contemporary West, Biu-Mandara, and East Chadic languages, it is not yet entirely clear whether the *-VC(V) formative belonged to Proto-Chadic or emerged independently as a later development in those branches. Newman (1990) has also suggested that Proto-Chadic likely used the reduplicative morpheme *CV- as the primary means for forming pluractionals, i.e. verbal forms denoting an action that is ‘done a number of times, by a number of subjects or affecting a number of objects’ (Newman, 2009, p. 620). Here too, the pluractional use of this formative is well attested in the West and Biu-Mandara branches, but it appears to be rare in East Chadic (Newman, 1990), and has not been reported for Masa.

Mattes (2017) describes the semantic categories of frozen reduplication or ‘lexical reduplication’ as she refers to this phenomenon.

In Gizey, clitics are “omni-locatable” (Dixon, 2010, p. 222) word-like forms attaching to the right (enclitic) of different constituent types (words or phrases) and different word classes (nouns, verbs, etc.) and which generally provide information about person/number, directionality, definiteness, etc. For example, the definite article =na (an enclitic) can be found after a noun (e.g., in [

]N=nā ‘things-pl2=art’ – ‘the things’) or after an extended NP (e.g. [[

]N=nā ‘things-pl2=art’ – ‘the things’) or after an extended NP (e.g. [[ ]N [má nàm l=ùm=íj]RC]NP=nā ‘things-pl2 rel 3sm do.pfv=3sm=res=art’ – ‘the things he did’) but still marking definiteness irrespective of the nature or size of its host.

]N [má nàm l=ùm=íj]RC]NP=nā ‘things-pl2 rel 3sm do.pfv=3sm=res=art’ – ‘the things he did’) but still marking definiteness irrespective of the nature or size of its host.Marba and Lew form a dialectal continuum which will be referred to elsewhere in this paper as Marba-Lew.

The glottal stop in the Marba-Lew form relates to restrictions on vowels occurring at word-initial position; the same restriction applies in Gizey and Masana.

On 124 Marba words with ʔà- (identified in (Ajello et al., 2001), there are about 5% which correspond to total reduplication in Gizey and 95% which occur in their base form.

Nominalization with *mV- might have undergone a decline in productivity in individual Chadic languages or branches (e.g., in Masa). This explains why it is no more attested in some languages or branches while others have maintained it.

Note in passing that the intensification expressed by the -CV(C) construction type can be negative or positive as shown with the Zime examples herɓi-ɓe ‘small termitary’ < herɓe ‘termitary’ and tindiŋ-diŋ ‘very dark’ < tindiŋ ‘dark’ (Vincent, 2000).

References

Ajello, R. (2007). The linguistic expression of spatial relation in the Gizey language. In H. Tourneux (Ed.), Topics in Chadic linguistics IV: Comparative and descriptive studies. Papers from the 3rd biennial international colloquium on the Chadic languages (pp. 9–21). Rüdiger Köppe.

Ajello, R. (2011). Anthroponyms in the Gizey society (N-E Cameroon). In M. Frascarelli (Ed.), A country called Somalia: Culture, language and society of a vanishing state (pp. 13–31). L’Harmattan.

Ajello, R., & Melis, A. (2008). Dictionnaire Gizey-Français, suivi d’une liste lexicale Français-Gizey. Pisa: Edizioni ETS.

Ajello, R., Mayore, K., Melis, A., & Ousmanou, D. (2001). Lexique comparatif de six langues du Tchadique central (Gizey, Ham, Lew, Marba, Masa, Musey). Pisa: Edizioni Plus.

Al-Hassan, B. S. Y. (1998). Reduplication in the Chadic languages. A study of form and function. Oxford: Peter Lang GmbH.

Allison, S. D. (2012). Aspects of a Grammar of Makary Kotoko (Chadic, Cameroon). Linguistics Graduate Theses & Dissertations, 16. https://scholar.colorado.edu/ling_gradetds/16?utm_source=scholar.colorado.edu%2Fling_gradetds%2F16&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages.

Ameka, F. K. (1992). Interjections: The universal yet neglected part of speech. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 101–118.

Anderson, S. R. (1992). A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bakker, P. (1987). Reduplications in Saramaccan. Studies in Saramaccan Language Structure: Caribbean Culture Studies, 2, 17–40.

Barreteau, D. (1978). Aspects de la morphologie nominale du Mofu-Gudur. In J. P. Caprile & H. Jungraithmayr (Eds.), Préalables à la reconstruction du proto-tchadique (pp. 95–113). SELAF.

Barreteau, D., & Dieu, M. (2005). Linguistique. In Atlas de la province Extrême-Nord Cameroun (pp. 1–32). IRD Editions.

Cetnarowska, B. (2020). Competition between synthetic NN compounds and NN.gen phrasal nouns in Polish: Semantic niches, hapax legomena and low-level construction schemas. In L. Körtvélyessy & P. Štekauer (Eds.), Complex words: Advances in morphology (pp. 241–259). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Colombel, V. de. (2005). La langue ouldémé (Nord-Cameroun). Grammaire, texte, dictionnaire. Leuven: Peeters.

D’Ascenzo, F. (2019). I Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad. In L. Gaffuri, A. Melis, & V. Petrarca (Eds.), Tessiture dell’identità. Lingua, cultura e territorio dei Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad. (Figure 1, p. 2). Liguori Editore.

De Dominicis, A. (2006a). Resyllabification phenomena in Gizey. In V. Giordani, V. Bruseghini, & P. Cosi (Eds.), Atti del terzo Convegno Nazionale dell’Associazione Italiana di Scienze dellaVoce 2006 (pp. 181–184). EDK Editore, CD-ROM.

De Dominicis, A. (2006b). Tonal patterns of Gizey. In A. De Dominicis (Ed.), Undescribed & endangered languages: The preservation of linguistic diversity (pp. 60–163). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press.

De Dominicis, A. (2008). Phonological sketch of Gizey. Studi Linguistici e Filologici Online, 6, 1–78.

Dixon, R. M. W. (2010). Basic linguistic theory volume 1: Methodology. London: Oxford University Press.

Dougophe, S. (2015). The Morphosyntax of Mafa verbs [Unpublished master’s thesis, Université de Yaoundé I].

Frajzyngier, Z. (2002). A grammar of Hdi. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Frajzyngier, Z., Johnson, E., & Edwards, A. (2011). A grammar of Mina. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110893908.

Frick, E. (1978). The verbal system in Dghweɗe. Linguistics, 212, 5–43.

Gaffuri, L., & Melis, A. (2018). Pour une géographie des lieux sacrés gizey. Géographie et Cultures, 107, 95–116.

Gaffuri, L., Melis, A., & Patrarca, V. (2019). Tessiture dell’identità. Lingua, cultura e territorio dei Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad. Napoli: Liguori Editore.

Gooden, S. A. (2003). The phonology and phonetics of Jamaican creole reduplication. [Unpublished PhD thesis, The Ohio State University].

Gravina, R. (2014). The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic: The reconstruction of the phonology and lexicon of Proto-Central Chadic, and the linguistic history of the Central Chadic languages. Utrecht: LOT.

Hüning, M. (2009). Semantic niches and analogy in word formation: Evidence from contrastive linguistics. Languages in Contrast, 9, 183–201.

Inkelas, S. (2008). The dual theory of reduplication. Linguistics, 46(2), 351–401. https://doi.org/10.1515/LING.2008.013.

Inkelas, S. (2014). The interplay of morphology and phonology. London: Oxford University Press.

Inkelas, S., & Downing, L. J. (2015a). What is reduplication? Typology and analysis Part 1/2: The typology of reduplication. Language and Linguistics Compass, 9(12), 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12166.

Inkelas, S., & Downing, L. J. (2015b). What is reduplication? Typology and analysis Part 2/2: The analysis of reduplication. Language and Linguistics Compass, 9(12), 516–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12152.

Inkelas, S., & Zoll, C. (2005). Reduplication: Doubling in morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jaggar, P. J. (2001). Hausa. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Jones, B. (2011). A grammar of Wangkajunga: A language of the Great Sandy Desert of North Western Australia. Canberra: Pacific linguistics.

Mattes, V. (2017). Iconicity in the lexicon: The semantic categories of lexical reduplication. Studies in Language, 41, 813–842.

Melis, A. (2006a). Dictionnaire Marba. Yagoua: CCMVL.

Melis, A. (2006b). Dictionnaire Masa-français: Dialectes gumay et ɦaara (Tchad). Napoli: Edizioni Plus.

Melis, A. (2019). Storia e identità linguistica. In Tessiture dell’identità. Lingua, cultura e territorio dei Gizey tra Camerun e Ciad (pp. 43–104). Liguori Editore.

Meyer, R., & Wolff, E. H. (2019). Afroasiatic linguistic features and typologies. In E. H. Wolff (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of African linguistics (pp. 246–325). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newman, P. (1986). Reduplicated nouns in Hausa. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 8, 115–132.

Newman, P. (1989). The historical change from suffixal to prefixal reduplication in Hausa pluractional verbs. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 11, 37–44.

Newman, P. (1990). Nominal and verbal plurality in Chadic. Dordrecht: Foris publications.

Newman, P. (2000). The Hausa language: An encyclopedic reference grammar. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Newman, P. (2009). Hausa and the Chadic languages. In B. Comrie (Ed.), The world’s major languages (2nd ed., pp. 618–634). London: Routledge. http://hdl.handle.net/2022/21482.

Newman, P. (2013). The Chadic language Family: Classification and name index. Mega-Chad research network / Réseau Méga-Tchad. http://lah.soas.ac.uk/projects/megachad/misc.html.

Novotna, J. (2000). Reduplication in Swahili. Afrikanische Arbeitspapiere, 64, 57–73.

Orgun, C. O. (1996). Sign-based morphology and phonology with special attention to optimality theory [PhD dissertation]. University of California.

Orgun, C. O., & Inkelas, S. (2002). Reconsidering bracket erasure. In G. Booij & J. Van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 2001 (pp. 115–146). Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-3726-5_4.

Pesetsky, D. (1979). Russian morphology and lexical theory. http://157.138.8.12/jspui/bitstream/11707/69/1/Posetsky.pdf.

Roberts, J., & Soulokadi, A. C. (2019). On ideophones in Musey. In H. Tourneux & Y. Treis (Eds.), Topics in Chadic linguistics X – papers from the 9th biennial international colloquium on the Chadic languages, Villejuif, September 7–8, 2017 (pp. 215–226). Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Schuh, R. G. (1998). A grammar of Miya. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Schuh, R. G. (2002). The locus of pluractional reduplication in West Chadic. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.488.2030&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

Schuh, R. G. (2008). Agentive nouns and derived verbs in Hausa. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f432/f6c46292a89fd895e8e2dfe260b35d90edf3.pdf?_ga=2.206889363.1200358648.1600339877-1009201699.1600250840.

Schuh, R. G. (2017). A Chadic Cornucopia. P. Newman (Ed.). Oakland: Department of Linguistics. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5zx6z32d.

Shryock, A. (n.d.). A dictionary of Musey. https://silo.tips/download/a-dictionary-of-musey.

Steriade, D. (1988). Reduplication and syllable transfer in Sanskrit and elsewhere. Phonology, 5, 73–155.

Stump, G. T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: A theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tourneux, H. (1978). Le mulwi ou vulum de Mogroum (Tchad): Phonologie-éléments de grammaire. Paris: SELAF.

Tourneux, H. (1986). La langue Mbara. In Les Mbara et leur langue (Tchad) (pp. 119–249). Paris: SELAF.

Viljoen, M. H. (2013). A grammatical description of the Buwal language. Victoria: La Trobe University.

Vincent, V. (2000). Le lexique Zimé-français (vun heɗe). http://zime.free.fr/lexique.htm.

Yu, A. C. L. (2005). Toward a typology of compensatory reduplication. In J. D. Alderete, A. Kochetov, & C. Han (Eds.), Proceedings of the 24th West Coast conference on formal linguistics (pp. 397–405).

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Mikhail Kissine and Philippe De Brabanter for numerous corrections, discussions, and suggestions. I am also very grateful to Yvonne Treis, Abbie Hantgan, Tatiana Nikitina, Izabela Jordanoska, Rogier te Paske, Ekaterina Aplonova, Silué Songfolo Lacina, Bethany Lycan, Olga Kuznetsova, two anonymous reviewers and Morphology’s editor for helpful suggestions. I am deeply indebted to Antonino Melis for always sharing his Gizey data with me. This work also benefited from numerous exchanges with members of the Labex EFL during my research visit at the LLACAN (Sept. 27 – Dec. 20, 2020).

Funding

My research is funded by the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) under the MINI ARC framework.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guitang, G. Frozen reduplication in Gizey: insights into analogical reduplication, phonological and morphological doubling in Masa. Morphology 32, 121–151 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-021-09389-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-021-09389-3

]N=nā ‘things-

]N=nā ‘things- ]N [má nàm l=ùm=íj]RC]NP=nā ‘things-

]N [má nàm l=ùm=íj]RC]NP=nā ‘things-