Abstract

In Tigre, the prefixes of the imperfective paradigm are undergoing a process of erosion. Especially for the prefix /t/, phonology plays a crucial role in determining whether it will be realized at all, and if it is, whether its surface form will be [t], [tə], [ta], or—most interestingly—gemination of the first root consonant. The pattern is strictly phonological, as it appears with all /t/ prefixes, inflectional or derivational. The paper provides an analysis of this phenomenon within the framework of CVCV Phonology (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004): the different government relations defined by the theory are shown to account for the distribution of /t/, and a principle of non-satisfaction of templatic material is proposed. This principle is confirmed by its ability to account, within the general framework, for the special form of stems with medial-gutturals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Tigre

Tigre is a Semitic language spoken in Eritrea by approximately 800,000 speakers. It currently has only one complete grammar, Raz (1983), which is based on the combination of Raz’s collected data, an earlier short grammar of Leslau (1945) and the data collected and documented by Littmann (1897, 1898, 1910–1915). The main focus and achievement of Raz (1983) is the detailed description of verbal morphology, a slightly more detailed version of which is found in Raz (1980). Further morpho-phonological information can be found in Palmer (1956, 1962).

All of this work was conducted with speakers of the Mansaʕ dialect. Indeed, this is the only dialect that appears in the literature, with the exceptions of the very partial grammar in Elias (2005), on the Habab dialect, and the word list from the Beni Amar dialect in Nakano and Tsuge (1982). The data in the present paper, in contrast, are based on work with a consultant who speaks the Samhar dialect, which to the best of my knowledge appears for the first time here. That said, as will become clear, the phenomena are (at least to some extent) shared with the Mansaʕ dialect.Footnote 1

Finally, it can be added that Tigre has not featured prominently in the theoretical literature on either Semitic or language in general. With only two exceptions (Lowenstamm and Prunet 1985; Rose 2003), which are unrelated to the present topic, this is the first time that any general theoretical aspect is studied based on this language.

1.2 Data

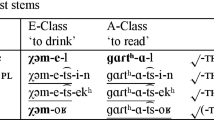

This study is concerned with the realization pattern of prefixal t- in the verbal system of Tigre. The relevant aspects of the system, presented in (1), are the following. There are three basic verb types. Every verb has a suffix conjugation, used for the perfective, and a mixed prefix-and-suffix conjugation, denoting the imperfective and subjunctive.

Verbal types are distinguished by the distribution of gemination and vowel length in the stem and the number of non-perfective stems. Type A verbs have distinct stems for imperfective and subjunctive, the former involving gemination of the second stem consonant, henceforth R2.Footnote 2 Types B and C have identical stems for the imperfective and subjunctive. Type B has gemination of R2 in both conjugations; type C has a long first vowel in both conjugations. The vocalization in Tigre depends not on the verbal type but on the aspectual features and on the number of consonants in the stem (geminated consonants counting as two). All verbs have a vowel [a]; when the stem has more than three consonants or a long vowel, a second vowel surfaces. This second vowel is [a] in the perfective and [ə] in the imperfective and subjunctive.

-

(1)

Tigre has five basic vowels /i,u,a,o,e/. Of these five vowels, only /a/ exhibits a length distinction (baʕal ‘master, owner’ vs. baʕa:l ‘holiday’, stress is final in both). The vowel [ə] is the epenthetic vowel of the language: it does not appear in the underlying representation, because its distribution is predictable on the basis of general syllabic principles.

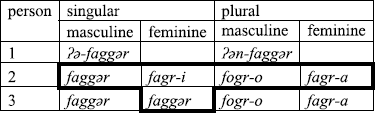

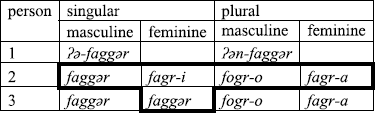

According to Raz (1983), a prefix tə- realizes two features in the inflectional paradigm: 2nd person and 3 sg. fem. All other 3rd person forms, including the 3 pl. masc. and fem., carry a prefix lə-. The [ə] that appears between the prefix consonant and the stem is probably epenthetic, since initial clusters are disallowed in Tigre (though exceptions will be discussed below). The imperfective conjugation is demonstrated in (2) for the type A verb—faggər ‘leave’ (henceforth, all the examples are from type A, unless stated otherwise). The same set of prefixes and suffixes appears on the subjunctive stem (with a different allomorph for the 1 pl.).

-

(2)

The prefixal inflexion of the imperfective (Type A), Raz (1983)Footnote 3

Raz further mentions that in colloquial speech the 2/3 person prefixes of the imperfective may be omitted. Voigt (2004, 2009) shows that this is true not only in colloquial speech, but in much written material, too. When I elicited the forms, I found that neither tə- nor lə- are ever pronounced in the general case, namely before stems of the form [CVCiCiVC], as the ones hitherto examined:

-

(3)

As already mentioned, Tigre does not generally allow initial clusters. Accordingly, the situation in (3) may be understood in the following manner. For some reason, in the Samhar dialect, the consonant of the prefix may not be followed by the epenthetic vowel *t ə -faggər. But if it is not followed by a vowel, it would have to form an initial cluster with the first consonant of the stem *tf aggər. This is also impossible, and so the prefix is dropped completely. These generalizations will be returned to in what follows.

As also mentioned by Voigt, in some cases, the prefixes always surface. These cases can be divided into two groups: 1) before consonant clusters; and 2) before gutturals.Footnote 4 The first scenario holds primarily under one specific condition. Gutturals never geminate in Tigre. Therefore, stems whose R2 is a guttural, do not exhibit internal gemination in the imperfective. Instead, the usual vowel [a] of the stem undergoes syncope, and the stem becomes cluster-initial: compare the imperfective stem -sʔəl- ‘ask’ to -faggər- ‘leave’ in (4). The result of this newly formed initial cluster is that both the prefixal tə- and the prefixal lə- are obligatory, as shown in (5):

-

(4)

-

(5)

Imperfective inflection: Guttural-medial rootsFootnote 5

The special stem of verbs with guttural R2 will be returned to in the last analytic section of this paper. For now, it is only important to note that the direct reason for the obligatory appearance of prefixes is not the guttural nature of R2, but the fact that the stem is cluster-initial.

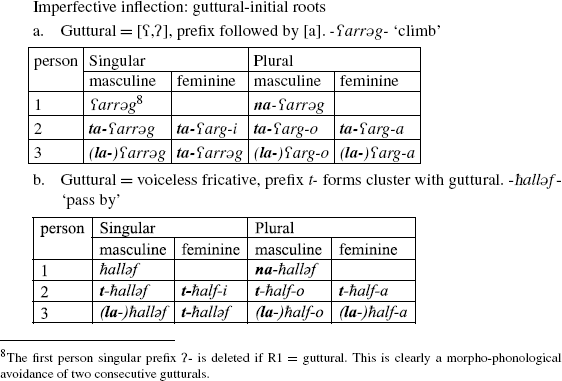

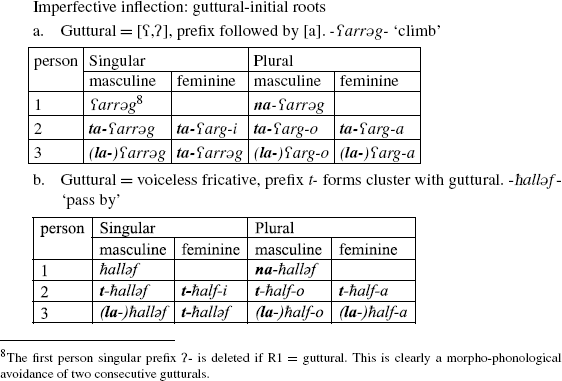

The second case in which prefixes are obligatory is when R1 is a guttural. These cases can again be subdivided into two groups. If the guttural is [ʕ,ʔ], then the prefix t- is obligatory, and the prefix l- is optional; both are vocalized with the short [a] (6a). If the guttural is a voiceless fricative [h,ħ], then t- is clustered to it, whereas l-, which is again optional, surfaces with the vowel [a].

-

(6)

Note that the cluster-initial forms in (6b) constitute an exception to the generalization made above, namely that Tigre does not have initial clusters. The situation in Tigre is thus typologically uncommon, with the only initial clusters allowed being tħ and th. Although a formalization of such clusters is included in the analysis in this paper, I take this uncommon typological fact at face value and do not attempt to explain it. The table in (7) summarizes the data presented thus far.

-

(7)

The realization patterns of the inflectional t- and l- in the imperfective

The state-of-affairs depicted in (7) was the one that emerged from elicitation of the forms in isolation. However, when the form was placed in a sentence, another peculiarity was detected, which is not mentioned in Voigt (2004, 2009). After consonant-final words, the situation was as in (7); but after a vowel-final word, the initial consonant of the stem was geminated precisely in those cases where there is never a surface prefix (i.e. the leftmost column in 7), as shown in (8a). Gemination appeared optionally when the overt prefix would have been /l/ (8b). When there was no surface prefix, and the first consonant was a guttural (this was only possible with /l-/), no gemination was attested (8c; as already mentioned, gutturals never geminate).

-

(8)

The same test was repeated with the negative circumfix yĭ-…-ni, and the same gemination was found. If so, an underlying /VtCiV/ sequence is realized as [VCiCiV], even though the first V belongs to a preceding word.Footnote 6 Notice, however, that this is only true of the prefix t-, and is not a general fact of Tigre: non-final closed syllables abound, and if [t] is their final consonant, it does not assimilate to the onset of the following syllable (e.g. katba ‘he wrote’). It is equally important to mention that the source of this gemination must be the underlying prefix. There is no general juncture rule that geminates word-initial consonants if the preceding word ends in a vowel.

In light of (8), the table in (7) has to be rectified as in (9), with C1 standing again for the first consonant of the stem.

-

(9)

The realization patterns of the inflectional t- and l- in the imperfective: rectified

The patterning of t- and l- seems to diverge. Whereas /t/ is always retrievable, /l/ may simply disappear in every context where it can be omitted.Footnote 7 For this reason, from now on, this paper will be concerned exclusively with the prefix t-. Restricting ourselves to /t/ then, its distribution seems to be quite straightforwardly determined by phonological markedness. A /t/ is always present underlyingly, surfacing as such when an initial cluster would result from its absence, and as gemination if, together with the first stem consonant, it is placed in the least marked position for geminates, namely the intervocalic position. Before gutturals, which do not geminate, [t] always surfaces; and its vocalization or lack thereof is determined by the possibility of it forming a cluster with the guttural.

This is nevertheless an informal explanation. Moreover, it presents at least one paradox: before stem-initial consonant clusters, the surfacing of [tə] may be interpreted as a means to prevent such an initial cluster; the same logic can account for the omission of /t/ before stem-initial CVs; but before guttural fricatives its surfacing instead creates such a stem-initial cluster. Indeed, if stem-initial clusters are possible, what prevents initial geminates? Of course, one may use a constraint such as *[wordCiCi, banning initial geminates, but that is merely stating what happens, not explaining it. The phonetic motivation for the lack of initial geminates is also clear, but surely, facts about acoustic salience do not make phonological accounts redundant.Footnote 8 , Footnote 9

The analysis in this paper is an attempt to account for the distribution of /t/ in a principled manner. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 briefly discusses why the phenomenon must be regarded as phonological, rather than morphological. Section 3 presents the framework of Government Phonology (Kaye et al. 1990) in its CVCV version (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004) and illustrates its various applications. Section 4 contains the account of the phenomena. Section 5 returns to the stems of verbs with R2 gutturals, and shows that their (sometimes) special form follows from the tools used to account for the distribution of /t/. Section 6 concludes.

2 Ruling out a morpho-phonological account: why this is not “lexical allomorphy”

The prefixal person marking we have been examining has four possible realizations: [t], [ta], [C] (a C-slot which would be filled by the first root consonant) and ø. This situation is classically referred to as “allomorphy”. But this term is confusing because, as is too often ignored, it groups together several distinct phenomena. First, one must distinguish between phonologically conditioned allomorphy and grammatically conditioned allomorphy, which has nothing to do with form. The case at hand is clearly of the first type. Within phonologically conditioned allomorphy, alternations in the form of a morpheme come in two flavors. In the first case, more accurately called lexical (phonologically-conditioned) allomorphy, there are two distinct, listed allomorphs, which are selected according to phonological considerations. In such a process, the input to phonology contains as many candidates as there are allomorphs, and the phonology selects the best candidate. In the second case, the morpheme has only one underlying form, but regular phonological processes alter this form. These processes do not take into account that this morpheme is a morpheme: they are just cases of phonology applying blindly to phonological representations. Unlike in the lexical case, allomorphy here is only a surface-based epiphenomenon, since there is only one underlying form. To distinguish this type of allomorphy from the previous type, let us call it “surface” allomorphy.

The case of allomorphy at hand, I submit, is one of surface allomorphy, and not of lexical allomorphy. There is only one underlying representation—to be defined in Sect. 4—whose phonetic realization is determined by strictly phonological processes. Before presenting my own analysis, I would like to briefly show that the opposite view misses two important generalizations.

In this opposite view there are four listed allomorphs—/ta/, /t/, /C/ and /ø/—which compete for insertion. Two objections to such an allomorphic account present themselves, one from inflection and one from derivation. First, if [ta], [t], C and ø are allomorphs, then one should ask what the morpheme is. Morphemes are usually presented as feature bundles (for instance in Distributed Morphology, Halle and Marantz 1993). The feature bundle here would have to express all second person forms and the 3sg.fm, to the exclusion of the all other 3rd person forms (regardless of gender). This is reviewed in (10), where the forms that consistently exhibit this alternation are framed (these are the forms that appear with [t] elsewhere):

-

(10)

Imperfective inflection of verb with sound root

This homophony of the 3 sg. fem. and the 2nd person is a trait common to all Semitic languages. Halle (2003) attempts to express it for Hebrew by designating [t] as the default marker, an attempt convincingly criticized in Harbour (2009). Harbour shows that [t] is the general marker of feminine gender in the language, and thus treating the 3 sg. fem. [t] as a default marker misses a generalization. He concludes that sometimes homophony is just accidental.

Harbour’s argument can be made even more forcefully for Tigre: whereas in Hebrew, the most prominent feminine marker is [a], which only reveals its underlying representation /at/ in some configurations, all feminine suffixes in Tigre involve a vowel and [t] (I have encountered at least four: [-ət, -it, -at, -a:t]). If so, like in Hebrew, there is no justification for unifying the 3sg.fm morpheme with the 2nd person morpheme. Thus, in order to maintain the lexical-allomorphic analysis, one would have to say that both the 2nd person morpheme and the 3sg.fm morpheme have the four allomorphs mentioned above, with exactly the same distribution. Such an account depicts this similarity as coincidental.

The second reason to reject this explanation is found in the passive form of the verb. Consider the pairs of active and passive forms in (11) ([tˈ] is an ejective consonant).

-

(11)

As evidenced in (11), passivization in Tigre is achieved by reduplicating R2 (unless it is a guttural (11d), see Sect. 5 below). In addition, a prefix [t] appears with exactly the same distribution as inflectional t-. Moreover, as shown in (12), exactly like the inflectional /t-/, in cases where the passive /t-/ is not detectable in isolation (such as 11c), it resurfaces as word-initial gemination if the preceding word ends in a vowel.Footnote 10

-

(12)

Further evidence for the underlying passive prefix /t-/ comes from the fact that all imperfective prefixes are obligatory in the passive paradigm. If the base [lakkafa] is underlyingly /t-lakkafa/, then the imperfective prefixes are expected to appear, since prefixes surface obligatorily before consonant clusters (5 above). As expected, the surfacing of the prefix is accompanied by the gemination of R1 (for very similar phenomena in the neighbouring language Tigrinya, see Kenstowicz 1982):

-

(13)

Imperfective inflection, passive: prefix obligatory, stem-initial geminate surfacesFootnote 11

I will return to the patterns in (13) in Sect. 4. For now, it is only important to conclude that the passive prefix behaves exactly like the inflectional prefix. This can only be understood if they are regarded as having the same underlying form. No other fact links the two prefixes. This strongly argues for a strictly phonological explanation for the phenomenon under investigation.

It is such an explanation that I develop in the two following sections.

3 The CVCV version of Government Phonology: general principles and gemination

This section introduces the theory that will be employed in the analysis, namely Government Phonology (Kaye et al. 1990) in its CVCV version (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004).

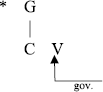

In CVCV phonology, representations include skeletal and segmental tiers. The skeletal tier is composed of strictly alternating CV units (14).Footnote 12 Thus, any consonantal cluster has an intervening V slot. This V-slot may remain unrealized, i.e. without phonetic exponence. The distribution of unrealized V-slots is controlled by the fundamental concept of Government, originating in Kaye et al. (1990:198), where it is defined as an “asymmetric relation between two skeletal positions.” Empty slots may remain without phonetic realization through “inter-constituent government”, one instance of which is a right-to-left relation between two consecutive nuclei. Within the CVCV version, this relation can be stated in the following manner:

-

A realized V-slot governs a preceding empty V-slot. When governed, empty V-slots may remain unrealized.

Ungoverned empty V-slots are ill-formed.Footnote 13 To illustrate, consider (14a). By assumption, there is an empty V-slot between the second and third consonants of halfa ‘he passed’. Because the nucleus to its right is realized, this empty position may remain unrealized. Now consider (14b), which is represented as having two consecutive, underlyingly unassociated V-slots: the final and penultimate ones (because the minimal unit is CV, all skeletal tiers end in a V-slot). Whether a final V-slot may remain silent or not is a parametric choice; as shown in (14b), in Tigre, it may. Still, as stated above, only realized V-slots may govern preceding ones. As a consequence, the penultimate V-slot in (14b) is ungoverned. It may not remain silent, and is therefore realized by association to the neutral vowel of the language [ə]. This, of course, is the process generally known as epenthesis; in Government Phonology, epenthesis is never the insertion a vowel, but rather the realization of an empty slot.

-

(14)

Representations in the CVCV version of GP, and the realization of empty nuclei

As can be deduced from (14a), word-internal codas are never primitive objects in CVCV. They are simply realized C slots followed by governed empty V-slots. The nucleus of syllable structure terminology is the V-slot of CVCV phonology. For the remainder of this paper, the traditional terms coda and nucleus will be used by convention; but these are not primitives of the theory adopted.

The case of three consecutive, underlying non-final empty nuclei CøCøCøCi has potentially two solutions. Either the first and third nuclei are realized (15a), or the middle one is realized. The choice may depend on factors such as the possible syllabifications in the language. Consider the case of the Tigre verb təsʔəli ‘you (sg.fem.) ask’. Assuming that the neutral vowel [ə] always realizes empty nuclei, and that all surface CC sequences are separated by empty V-slots, the underlying representation of this word must be /tøsøʔø li/. In Tigre, as mentioned, gutturals may not be realized as word-internal codas, i.e. immediately preceding a consonant. Thus, V3 in (15a) will have to be realized regardless of government. This results in the governing of V2 and the realization of the ungoverned V1. The other option, presented in (15b), is ruled out because of the ban on coda gutturals. (This is a hypothetical form; V1 would in principle have to be realized regardless of government, because of a ban on initial clusters.) The surface distribution of gutturals will be formalized in Sect. 5.

-

(15)

Another effect of the government relation is to render positions available for linking to the segmental tier. For instance, Lowenstamm (1996) uses government to account for closed syllable shortening (whereby long vowels cannot appear in closed syllables). In an open syllable, the second V-slot of the long vowel is made available through government by a following non-empty nucleus, and thus is a legitimate target for spreading (16a); but in a closed syllable, that position is not governed by the following V-slot, which is itself governed, and the vowel cannot be long (16b). Note that government is not a relation between vowels—if it were, the second [a] of [safrat] would be able to govern the same position as the [ə] of [saafər]; it is a relation between nuclei.

-

(16)

The outcome of this government relation is that the slot is available for linking to the segmental tier. The availability of a slot through government is called “licensing”, and the slot is referred to as “licensed”.Footnote 14

Licensing is also the outcome of the government of a C-slot (or Onset) by the following V-slot. A non-empty V-slot licenses (through government) a preceding C-slot, i.e. it ensures the C-slot’s availability to autosegmental processes. Thus, a floating /l/ can attach to the position in (17) because it is licensed by the realization of the following nucleus.

-

(17)

Onset licensed through government by Nucleus

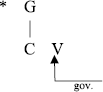

In CVCV, the representation of consonant clusters always contains a cluster-internal nucleus (although see Lowenstamm 2003). Like any other nuclei, such nuclei must be governed in order to remain unrealized. However, Scheer (1999:294) suggests a government relation that holds between segments, which he terms “Infrasegmental Government” (IG). Scheer’s definition involves terminology and analyses that needn’t concern us here; the following definition will suffice:

A segment S1 may govern a preceding segment S2 if S1 is more sonorous than S2.

Because the skeletal tier is composed of strictly alternating C’s and V’s, such government always holds across an empty nucleus. This creates a domain, and the intervening V is “saturated”: it does not require government in order to remain unrealized (Scheer 1999:299). This idea is used, for instance, to explain why certain French vowels are pronounced as if in an open syllable before such clusters (French /e/ becomes [\(\upepsilon\)] in closed syllables, see e.g. Morin 1986), as shown in (18). Infrasegmental Government is marked by an arrow “<=” with the initials IG:

-

(18)

Infrasegmental Government: French débris ‘debris’

Infrasegmental Government is thus CVCV’s manner of representing what in less theory-specific terms is a “branching onset”, or “tautosyllabic” initial clusters. In the rest of the paper, the term “cluster” is used only for the adjacency of tautosyllabic consonants, to the exclusion of coda-onset clusters such as ka tb a ‘he wrote’.

Infrasegmental government has the important effect of “saturating” the intervening V-slot, such that although this slot is empty, it does not have to be governed by the following V-slot in order to be phonetically null. Saturation is central in the account of initial clusters. For that majority group of languages which do not allow any possible cluster word-initially, to which Tigre belongs, one may assume that such clusters are in fact disallowed in general, and surface only under certain conditions.Footnote 15 IG provides one such condition.

To illustrate, consider the two words from Modern Hebrew in (19). In (19a), an IG domain is built between the [m] and preceding [š]. The engulfed nucleus, despite its initial status, remains unrealized. In contrast, such a domain cannot be built around the cluster [lv] in (19b), owing to the internal make-up of the two segments.Footnote 16 The engulfed nucleus, being the first nucleus of the word, is not governed and thus must be realized.

-

(19)

Modern Hebrew: šmor ‘keep!’, levana ‘white (fm.)’

This view also explains why initial geminates are very marked. CVCV phonology maintains the autosegmental view of the geminate as a single segment linked to two C-slots.Footnote 17 Like clusters, geminates require the contained nucleus to be governed; unlike clusters, this requirement can never be satisfied by IG, because a segment cannot govern itself. In other words, a domain may never be created around a geminate, and the intervening V-slot of a geminate must be governed from the right.

-

(20)

Gemination requires government of intervening V

The markedness of geminates follows from the representations in (20) in combination with the other principles discussed above. The condition in (20) rules out geminates that are not followed by a vowel, i.e. internal-coda geminates and word-final geminates. The general notion of government explains why geminates may not appear after a coda: a sequence CVCjøCiøCiV would leave the first empty nucleus ungoverned. Finally, we saw that initial clusters are only possible through IG, and geminates cannot be IG domains.

That said, the Tigre data of the previous section did contain some intriguing cases of initial geminates. Having surveyed the types of government that hold in the adopted theory, we are ready to move on to the analysis of those data.

4 The distribution of /t-/ in Tigre accounted for in the CVCV version of Government Phonology

In this section, it is shown that the set of government relations presented in the previous section, complemented by the conditions on geminates and the interaction with nuclei preceding the word, can accurately account for the distribution of the /t/ prefixes in Tigre. This is achieved in three moves. First, a “floating” representation of the prefix is proposed. Then, the floating /t/ is shown to be allowed to link to the skeleton only under specific conditions, which are provided by guttural- or cluster-initial stems. Finally, cases where /t/ is not realized, or realized as a geminate, are treated. The data to be accounted for are recalled in (21):

-

(21)

The realization patterns of the inflectional t-

A note on the spirit of the analysis is due. Throughout the analysis, I assume underlying representations involving a skeletal tier and a segmental tier. In each specific case, the concatenation of morphemes raises problems regarding the mapping between the two tiers. For each problem, several solutions are raised, and the analysis strives to judge in favor of the attested solution using independently motivated principles of mapping. This consideration of different mapping strategies recalls the spirit of Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993), which assumes the existence of a computational mechanism of competition and evaluation. The present analysis, while it is not incompatible with such a view, concentrates on universal motivations for structural possibilities and impossibilities.

4.1 The representation of /t/

The double-tier approach adopted here allows for several types of representations for morphemes (Clements and Keyser 1983; see elaborate discussion in Bendjaballah and Haiden 2008). For those morphemes that have segmental content, such as the various /t/s we have been examining, there are three possible representations: either the segment does not have a skeleton of its own (22a), or it does. If it does, the link between the segmental tier and the skeletal tier can be pre-specified (22b) or not (22c).

-

(22)

Morphemes with representations of the first type are expected to interact with the size of the base, since they will need the skeleton of the base in order to be realized. This does not seem to be the case for the Tigre prefixes under examination. The difference between (22b) and (22c) is that in the latter, the linking of the segment to the skeletal tier—resulting in its realization as such—is dependent on its environment. (22c) is thus clearly the best representation of the prefix /t/ in Tigre, which as we saw, does not always surface as [t].Footnote 18

4.2 Licensing: when /t/ surfaces as [t]

In the previous subsection, we have established that /t/ is a floating segment. As such, its linking must be licensed. In CVCV phonology, as we saw above, such licensing can be achieved through the realization of the adjacent nucleus (17). We have also seen that licensing is the outcome of government: this opens up another possibility for the licensing of a consonant, namely through Infrasegmental Government (18). In this subsection, it is shown that the three environments in which /t/ is realized as [t] involve licensing in one of these two ways. Furthermore, it will be shown that whether the previous word ends in a vowel or a consonant has no effect on the licensing of /t/. (This is important for the ensuing sections.)

First, consider the case of stem-initial clusters, appearing most straightforwardly in type A imperfective stems with R2 gutturals tˈʕən ‘load’. As depicted in (23), the empty nucleus of the stem is governed by the only stem vowel. As a result, that first nucleus cannot govern the nucleus of the prefix, which has to be realized. Because the nucleus of the prefix is realized, the /t/ is licensed by V-to-C licensing. Because relations are strictly right-to-left, the reasoning holds whether the final nucleus of the preceding word requires government or not.

-

(23)

Prefixal V ungoverned and realized, /t/ linking licensed by V-to-C licensing

In (23), it is assumed that a governing relation may hold between the first nucleus of a word and the final empty nucleus of the preceding word. This is slightly problematic, because as mentioned, word-final empty nuclei are parametrically allowed in Tigre: words may end in consonants. If this is the case, why then does the final nucleus of the preceding word require government? On the other hand, as the data in this paper show, there is certainly interplay between the right edge of a word and the left edge of a following word in Tigre, and that interplay is affected by whether the final nucleus is occupied or not. I suggest to resolve this in the following fashion: final empty nuclei may parametrically be allowed, but only if a government relation cannot be established in the linearization between such nuclei and following, realized nuclei.Footnote 19

Moving on, an account similar to (23) can be provided for the case of stem-initial guttural stops which are not [+continuant, -voice]. As shown in (6a), in this case, the prefix t- appears with the vowel [a]: /t-ʕarrəg/ => [ta-ʕarrəg] ‘you climb’. The appearance of [a] after the prefix t- can be regarded as originating in the stem vowel: spreading across glottals is well-attested cross-linguistically, and for those languages that have pharyngeals, vowels are particularly likely to spread across pharyngeals, too (for instance, Tiberian Hebrew /niʕmad/ => [neʕemad]). In the Tigre case, one need only assume that the prefixal nucleus is filled through copy, as shown in (24). Just like in the representation in (23), because this prefixal nucleus is realized, the /t/ is licensed by V-to-C licensing; again, whether the preceding word ends with a vowel or not is irrelevant.

-

(24)

Prefixal V filled by copy, /t/ linking licensed by V-to-C licensingFootnote 20 , Footnote 21

As recalled above, the underlying /t/ is also realized as a consonant [t] before guttural fricatives. In this environment, however, /t/ is not followed by a vowel, but rather clustered with the guttural fricative: /t-ħalləf/ => [tħalləf]. Evidently, Tigre allows for initial [tħ] and [th] clusters. As the reader will recall, clusters are formed by Infrasegmental Government. Consequently, [t] is licensed and may link to the C-slot. Furthermore, a domain is created, and the nucleus contained in that domain does not require government (it is “saturated”). As a result, an empty nucleus preceding the domain can be governed across that domain by the vowel of the stem.Footnote 22

-

(25)

Prefixal V saturated by domain creation. /t/ linking by Infrasegmental government.

In (25), the first realized nucleus of the stem governs the nucleus preceding the infrasegmental domain, i.e. the nucleus of the preceding word. In other words, even if the preceding word ends in a consonant, this would have no bearing on the realization of /t/ as clustered with the stem-initial guttural fricative.Footnote 23

To summarize this subsection, it was shown that the cases in which the /t-/ maintains its underlying quality can all be accounted for by assuming the following:

-

1)

This /t/ is not lexically linked to a skeletal position; and

-

2)

The linking of floating segments is licensed through government.

In the next subsection, cases where /t-/ disappears or assimilates are discussed.

4.3 When /t/ may not link: omission and gemination

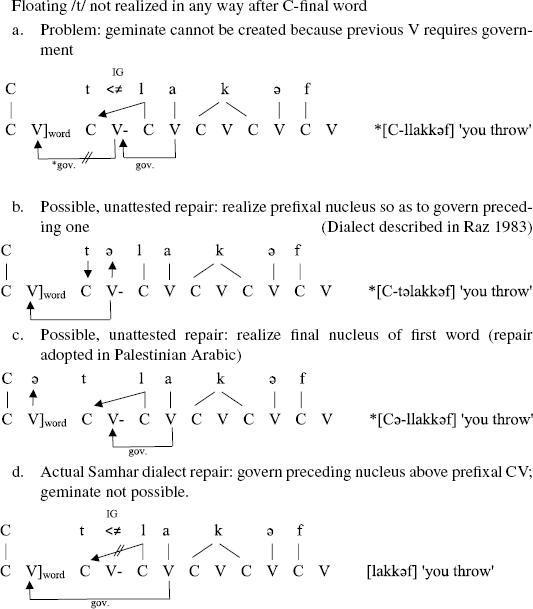

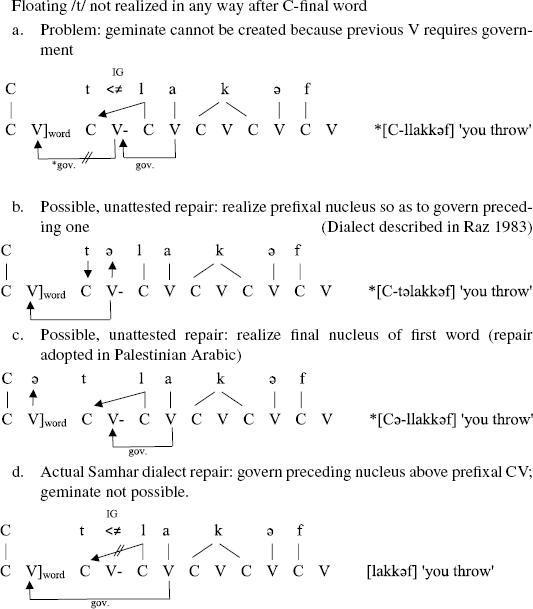

As exemplified in the data section, before CV-initial stems, /t/ is omitted if the previous word ends in a consonant. If the previous word ends in a vowel, /t/ assimilates to the next consonant to form a geminate. In this section, these reflexes of /t/ are shown to follow from the general principles discussed in previous subsections.

The case in point is /tlakkəf/ ‘you throw’. In (26), it is presented after a word that ends in an empty nucleus. The /t/ remains afloat because it is not licensed either by the nucleus adjacent to it or by the following consonant (recall that the only word-initial clusters allowed in Tigre are [th] and [tħ]; in CVCV phonology, we may assume that Infrasegmental Government thus may not hold in clusters such as /tl/). This latter nucleus cannot license /t/ because it is itself governed and thus unrealized. Because the prefixal nucleus is governed, a possible candidate to occupy the C-slot of the prefix is the stem-initial consonant: this is so because the condition for gemination in (19) above is met. But if the prefixal nucleus is governed in this manner, and a geminate is formed, then no government of the empty V slot of the preceding word is possible. (26a) is simply ill-formed.

There are three ways to “repair” the situation in (26a). One is to realize the prefixal nucleus, yielding [təlakkəf] (26b). Another is to realize the word-final empty nucleus, yielding [əllakəf]. Both of these solutions, which the Tigre documented here does not adopt, are possible. The first is exactly the form cited by Raz (1983). The second solution happens in Palestinian Arabic (Elihai 2004), where the final empty nucleus of a word is realized when the following word begins in a cluster: walad ‘boy’, kbir ‘big’; [waladəkbir] ‘big child’. This possible repair is shown for the Tigre situation in (26c). However, the repair in the Samhar dialect of Tigre is a third one, namely to ignore the prefix CV and apply government above it, as if it weren’t there (26d). This is undoubtedly related to the floating status of the prefixal /t/.

-

(26)

In the proposed solution, the first vowel of the stem governs the final, empty nucleus of the preceding word. The floating /t/ cannot be associated to its position in the prefixal CV, because the nucleus is not realized. But that same CV may not be associated to the first stem consonant either, because gemination requires the engulfed nucleus to be governed; that nucleus is not governed, because its potential governor governs the empty nucleus terminating the preceding word.

This repair scenario yields the correct result. And yet, it raises a problem, in that it leaves one CV unit—that of the prefix—completely unoccupied. Such CV units are referred to as “unidentified” in CVCV phonology (Guerssel and Lowenstamm 1996). Unidentified CV units are a problem, if only because the basic motivation for having a skeletal tier is to impose a certain form on the segmental material through Template Satisfaction (McCarthy 1981). If one assumes that such unidentified skeletal units may remain empty (or simply drop) for no particular reason, then the entire idea of templates is undermined.Footnote 24 I suggest instead that such units remain in the template under a very specific condition:

-

(27)

Principle of unidentified CVs

A CV unit may remain unidentified if a relation of government holds above it.Footnote 25

This principle is admittedly ad-hoc. It is also circular: as things stand now, it can only be motivated by its ability to account for what it was invented to account for, i.e. the lack of gemination. However, in the next section I will return to it and show that it is active in another, related phenomenon in the language.

But let us first return to the case of /tCV/. As shown above, another realization of /t/ is through the gemination of the following consonant. This occurs when the preceding word ends in a vowel: /səga tlakkəf/ => [səga llakkəf] ‘you throw meat’. As (28) illustrates, this is exactly what is predicted by the analysis: once the nucleus of the preceding word is full, it does not require government, and the stem-initial vowel can instead govern the prefixal nucleus. The floating /t/ cannot link, because its position is not licensed, and it is not governed by Infrasegmental Government. The C position remains unidentified: in order to identify it, the first consonant of the stem spreads leftwards. A geminate surfaces:

-

(28)

Floating /t/ results in gemination after V-final word

This last representation concludes the discussion of the realization of /t/. No further stipulation needs to be added. However, to be explicit, another representation should be provided, namely the representation of the inflected passive imperfective /t-t-lakkaf/. Since the passive /t/ exhibits the same phonological behavior as the person prefix /t/ word-initially, I will assume that its representation is identical: it is an unassociated, floating segment. If so, in /t-t-lakkaf/ ‘you are thrown’, we have two consecutive floating /t/’s. As the reader may recall from (13) above, in this case, the first of the two floating /t/’s is obligatorily realized, and the second forms a geminate with the first stem consonant, yielding [təllakkaf] ‘you are thrown’. As the representation of this form in (29) illustrates, this pattern of realization is the one predicted, regardless of the form of the preceding word.

-

(29)

Two floating /t/’s: the first realized, the second geminated

To summarize this analytic section, by assuming the relations of government and their effects on gemination and realization, and by integrating the relation with the final nucleus of the preceding word, we have succeeded in accounting for the pattern of realization of /t/ in a strictly phonological manner.

One stipulation nevertheless remains unmotivated, namely the principle of unidentified CVs in (27). In the next section, which explores the consequences of the analysis, we will see that the principle is independently motivated by its ability to explain the special form of guttural-medial stems in type A, and the lack of a special stem in guttural second passives.

5 Further investigations: unidentified CVs motivated by the case of guttural-medial stems

This section expands the analysis beyond the realization of /t/. More specifically, it is shown that the principle of unidentified CVs can account for the existence of special stems for guttural-medial verbs in type A, but not in passives.

In the introductory part of the paper, guttural-second stems in type A were presented as having an exceptional form: whereas regular stems have a medial geminate and a vocalization <a,ə> (e.g. -kattəb- ‘write’), guttural-second stems have no geminate and only a vowel <ə>, e.g. -sʔəl- ‘ask’.Footnote 26 The reason for this change was stipulated to be the ban on guttural geminates, *saʔʔəl. That said, what is wrong with *saʔəl? In other words, why is the [a] vocalization syncopated? For the present purpose, let us assume that this syncope occurs because it can occur in this environment, whereas in the case of non-guttural medial roots it may not. This analysis, as we shall now see, is possible only if one accepts the principle of unidentified CV (27) above.Footnote 27

First, let us formalize the ban mentioned above. Gutturals are not only illegitimate geminates; they are also ruled out in word-medial coda position. To illustrate, recall that the 3 sg. masc. stem of type A perfectives is katba ‘he wrote’, but guttural-medial 3 sg. masc. stems have an epenthetic [a] after the guttural, e.g. saʔ a la ‘he asked’. In CVCV, this ban can simply be stated as “gutturals may not precede governed empty nuclei” (30). This formalization rules out guttural geminates (the first part of a geminate always violates (30)) while at the same time allowing word-final gutturals (final empty nuclei are allowed parametrically, not through government).

-

(30)

Gutturals may not precede governed empty nuclei

In order to account for the exceptional form of guttural-medial stems in the imperfective, one has to place them in the same template as regular stems, namely the template that requires gemination and has an <a,ə> vocalization. This is represented in (31a). The problem is clear: The first C-slot of the geminate guttural is governed, in violation of (30). As a result, only the second C-slot is realized, as shown in (31b). However, in this case, while the V-slot is governed and may remain unrealized, the left C-slot (in bold) is unidentified. Once again, allowing for parts of the template to remain unidentified is a bad choice on principled grounds. Moreover, since the basic skeletal unit is CV, either both C and V are identified, or both are unidentified: identification must apply to both or to neither.

The repair in (31c) thus crucially involves the principle of unidentified CV: a CV unit may remain unidentified if a relation of government holds across it. Thus, a relation of government is established across the unidentified CV unit, from /ə/ to /a/. Since /a/ is short, and since its nucleus is governed, its linking is undone and a stem-initial cluster results.

-

(31)

Of course, there are other possible repairs to (31b). For instance, the short vowel /a/ could lengthen to occupy the unidentified CV. The fact that the vowel is syncopated here undoubtedly has to do with the presence of a following guttural: the length distinction between /a/ and /a:/, which is attested elsewhere in the language, neutralizes before gutturals, and /a/ syncopates before gutturals in Tigre in several other morphological scenarios.Footnote 28 Very schematically, it seems that short /a/ before a guttural behaves as if it were the effect of the guttural, and the nucleus would otherwise be empty. Whatever the correct analysis of pre-guttural /a/-syncope is, it must, like any syncope, involve government, and as mentioned, an unidentified CV remains. The repair thus crucially requires the principle of the unidentified CV. This principle, which required further motivation in the preceding section, is shown here to be independently active, underlying the emergence of special guttural-medial stems. I consider this sufficient motivation.Footnote 29

Interestingly, however, not all guttural-medial stems syncopate in the perfective. As (32) shows, the first vowel of imperfective passive stems does not syncopate.

-

(32)

Imperfective stems of active vs. passive

active

passive

-tˈʕən

-tˈaʕan

‘load’

-sħəb

-saħab

‘smoke’

-sʔəl

-saʔal

‘ask’

However, the forms in (32) do not constitute minimal pairs because, as the careful reader will recall, the stem of the passive in the imperfective also contains the passive prefix /t-/ (as opposed to the inflectional one). Thus, the structure of the imperfective passive stem should be represented as in (33). As can be seen, the second nucleus of the stem may very well govern the preceding nucleus, but the latter may not syncopate, because it is needed in order to govern the nucleus of the passive prefix. Compare this to (31c), where the first vowel of the stem does in fact syncopate.Footnote 30

-

(33)

The imperfective stem of passives: [(s)saʔal] ‘be asked’

Of course, another possible scenario would consist of the syncope of the first /a/, followed by the realization of the first nucleus and the passive prefix, yielding *təsʔal. To rule out this scenario, one can assume that lexical vowels which entertain government relations may not be syncopated. This allows the first vowel of the stem in (31) to syncopate, because it does not entertain a government relation in the stem. Given this, when one considers the stems—that is, the inputs to inflection—of both active and passive guttural-medial verbs, the principle of unidentified CVs correctly predicts where the first vowel of the stem will undergo syncope and where it will resist syncope. The analysis suggests that Tigre allows for initial empty nuclei in its lexical representations, whether their first consonant floats or not; phonological factors then decide whether all skeletal positions will be realized or not. Having motivated this speculation, we now move to conclude the paper.

6 Conclusion

This paper has served two goals. First, it described in detail the phenomenon at hand, namely the erosion of the second and third person prefixes in Tigre in certain phonological contexts. A central fact, presented here for the first time, is that this erosion gives rise to a sort of liaison at the left edge of the word, with the eroded consonant surfacing together with the following consonant as a word-initial geminate when the preceding word ends in a vowel. This is true of all prefixed /t/’s, regardless of the morphological content expressed.

The second goal of the paper was to provide a strictly phonological account of the distribution of the prefix /t/. The possibility that this is not a phonological phenomenon was rejected. An account was then provided within the CVCV version of Government Phonology. Rather than assume a ban on what is clearly ruled out in the data, the analysis attempted to cover the array of realizations through independently motivated structural relations between skeletal positions and between segments. The analysis showed that government relations between words, that is between the first nucleus of a word and the final nucleus of the preceding word—these relations are responsible for word-initial gemination or lack thereof. The interactions of /t/ with stem-initial gutturals were also explored and accounted for. Finally, principles that were employed in the analysis of /t/ were shown to shed light on the independent phenomenon of stem-allomorphy in guttural-medial stems.

A final word is due on the formalization of erosion that this paper implicitly advocates. It is well-known that many grammatical markers started out as independent words or pronouns, then came to be morphologized and dependent, and then gradually eroded phonologically before disappearing altogether (Hopper and Traugott 2003). This paper provided a formalization of a synchronic, intermediary stage in that process: phonological effects (avoidance of clusters), probably enhanced by other factors (such as frequency and context-induced redundancy), amount to the disassociation of the prefix /t/ from its skeletal position, thereby causing a host of alternations. In Tigre, as I tried to show in this paper, the alternations of the /t-/ prefixes remain within the realm of phonology. The next step—arguably illustrated by the distribution of /l/—is to render the marker not only lexically unassociated, but also grammatically optional.

Notes

The fieldwork was conducted with Mohammad ʕabdu, a political refugee living and working in Israel. Mohammad is aged 22 and comes from the town of Gindaʕ. Other Tigre speakers of the same dialect were not found in Israel.

“R” stands for Radical: in fact, rather than the consonant of the stem, it is the second radical, the second consonant of the root, which is geminated. Although this distinction is important for the understanding of the system, the analysis in the present paper does not rely on it.

The issue of the underlying representation of the first person prefix is not taken up in this paper. It is possible that both here and in the following paradigms, the [ʔ] of the prefix is epenthetic.

The term “guttural” designates a consonant that is articulated towards the lowest end of the vocal tract. In Tigre, as in other Semitic languages, the gutturals are the glottals [ʔ] and [h] (whose major articulator is the glottis) and the pharyngeals [ʕ] and [ħ] (articulated by bringing the back of the tongue toward the pharynx, the area just above the glottis). These consonants exhibit uniform behavior in many Semitic languages. For the phonological aspects of gutturals see Bellem (2007) and references therein.

In the suffixed forms, the [ə] of the stem persists even though its position is governed by [a] (for government, see Sect. 3 below). As elaborated upon in Sect. 5, gutturals may not precede unrealized nuclei. Also notice that the 1 pl. prefix is ne- and not ʔən-. As mentioned, I will not be concerned with 1st person prefixes in this paper.

Of course, for this gemination to occur, the preceding word has to be close enough—in some well-defined sense—to the prefixed verb. As far as I have been able to check, the relevant unit here is the utterance: no syntactic boundaries seem to block the process.

One may wonder why /l/ may disappear completely, but /t/ cannot do so. The most sensible answer, in my opinion, comes from the nature of the morpho-syntactic features realized. /l/ realizes the 3rd person. Null realization of the 3rd person is common cross-linguistically, possibly because the features are simply not there: the third person is the lack of person (Benveniste 1956; for a recent application and discussion, see Walkaw 2009). Notice that this argument is not countered by the obligatory nature of 3 sg. fem. /t/, which also realizes a feature [gender].

Raz (1983:56) describes passive formation as having a prefix tə- and a medial geminate. This prefix, he says, is optional. If it appears, it optionally assimilates to following dentals, alveolars and palato-alveolars. In my data, the prefix is not optional—it always surfaces as gemination when this is possible—nor does it assimilate only to coronals ((b)ballaʕaˈ he was eatenˈ).

A fact worth pointing out here is that this template, which we might call tQaTTaL, applies to verbs of all types. Recall that type B verbs already have inherent R2 gemination (mazzana ‘he weighed’). As a result, like type A guttural medial stems (11d), perfective type B stems with non-guttural R1 are homophonous with their passive counterpart (mazzana ‘he was weighed’ < /tmazzana/). The identity is accidental. In the imperfective, the passive is vocalized with [a,a], the active with [a,e], and the underlying presence of passive /t/ renders obligatory the inflectional prefix, thus allowing the initial geminate to surface: mazzən ‘you weigh’ vs. təmmazzan ‘you are weighed’.

In the passive imperfective, the /t/ prefix may also surface as [t]: tə t lakkaf ‘you are thrown’.

CV units are not to be confused with syllables in the common sense of the word, which would divide a word like ħalfa to two constituents ħal.fa. They are, rather, syllabic constituents. The common sense of “syllable” can be constructed from the CV tier in a principled manner (see for instance Scheer and Szigetvári 2005).

See Bérces (2006) for empty C-slots.

At first glance, it seems that government and licensing are conflicting forces. Government inhibits the realization of a nucleus by allowing it to remain unrealized, while licensing, whose vector is the relation of government, renders the slot available for realization. Indeed, Scheer (2004) views the two relations as independent from one another. Still, I see no conflict: government allows a slot to remain unoccupied. Thus, it is available as a target for autosegmental processes, if such processes are independently called for. In (15a), the governed position is preceded by an occupied C-slot, and so the vowel need not spread to the following position (under the assumption that all these phenomena hold after Tier Conflation, McCarthy 1981). The reverse is true in (16a). The vowel must spread, or the middle CV will remain unidentified (see Sects. 4 and 5 for identification problems). For the remainder of this paper, however, I will use government for the inhibiting force and licensing for the facilitative force.

Lowenstamm (1999) analyzes the restrictions on initial clusters in such languages as caused by the presence of an empty CV unit preceding the word, which requires government from within the word. This parametric account claims that languages where any cluster is allowed simply do not have this initial CV unit. The details of this analysis were developed in Tobias Scheer’s work (2004 et passim.), but stand outside the scope of the present paper.

These make-ups can be found in Scheer (1999).

The representation of geminates has been the subject of a long debate in generative phonology: see Davis (2011) for an overview and arguments in favor of a moraic, rather than a timing-slot representation. As shown in Scheer and Szigetvári (2005), CVCV phonology does away with at least some of the motivation for moras, so the option advocated by Davis is not available within this theory.

Recall from the introduction that not all syllable-final /t/’s assimilate to a following adjacent consonant. This is only true of the t- prefixes. For this reason, too, the floating representation in (22c) is a good analytic choice for these consonants. However, I do not go as far as to claim that all C∼ø alternations are due to such representations: delinking processes are another analytic possibility. See Kenstowicz (1994: Chap. 8) for discussion.

An alternative pointed out by a reviewer is that final empty nuclei are only allowed phrase-finally. The phrase final variant would also be the citation form.

A reviewer asks why the [a] of the stem does not govern the preceding nucleus, thereby doing away with the /t/ prefix. That would leave the final nucleus of the preceding word ungoverned, an option that is unavailable in Tigre (see discussion around 26). Moreover, as explained in (28), the guttural would then have to geminate, and gutturals in Tigre never do (as elaborated upon in Sect. 5). That said, the repair in (26d), with government holding across the prefixal CV, would work here; I assume that the copy option is preferred to leaving an unidentified CV.

The regular from in (24) contains more CV units than the guttural-medial one in (23). See (31) below, and the discussion around it, for an explanation.

A discussion of the formal conditions for forming a domain is beyond the scope of this paper. Still, besides IG, another possibility is that of the potential of the second element to constitute a secondary articulation for the first. This is how Lowenstamm (1996) analyzes Chaha palatalization.

Lowenstamm (2003) voices doubts about the existence of any branching onsets, based on their irrelevance for the calculation of stress. He represents such clusters as occupying a single C-slot. With very little additional stipulation, the analyses in (25) could work with such a view, too.

In CVCV phonology, the concept of template satisfaction is extended to all representations, whether the morphology is templatic or not. For this reason, whether the t- is part of the lexical template of the verb or not is irrelevant to the discussion: once there is sufficient reason to believe that t- is accompanied by skeletal material, as the realization of the t- elsewhere suggests, the omission of that material is an analytic option that would fatefully weaken the theory.

This is of course only one way that unidentified CV units can be dealt with. Larsen (1998) discusses such units as the source for Italian raddoppiamento sintattico or stød in Danish. However, these solutions imply that the units are eventually identified, whereas (27) offers a principle for the persistence of a CV unit in the template even though it has not been “engaged” in any way.

Interestingly, Raz (1983) reports that there are no guttural-medial roots in type B, and only some in type C. The lack of such roots in type B can be straightforwardly accounted for by the fact that gutturals do not geminate: the stems of types A and B would end up being identical. A guttural-medial root in type C would have the stem /Qa:GəL/. Since there is no distinction between short and long /a/ before gutturals, such a stem would differ from the stems of types A/B only in that its [a] vowel would not syncopate in the imperfective (because of its underlying length). Since this would be the only clue, such type C roots are likely to switch paradigms to the common type A/B. In fact, it is unclear whether such verbs exist at all: I recorded none, and Raz reports only the passive counterpart of three such verbs, but, as explained in this section, the [a] of passives never syncopates, so it is really not possible to distinguish type C passives from the passives of other types.

The analysis in this section represents guttural-medial stems unlike their representation in the main analysis (23). However, the two representations are completely compatible, (23) being a simplified version of the representation in this subsection.

Consider, for instance, the case of the suffixed imperatives of type A: they are of the from QəTaL- for regular roots (e.g. fəgar-i ‘leave (fm.sg)’) but QəTG- for guttural-final roots (e.g. bəlʕ-i ‘eat (fm.sg)’). See Faust (2014) for a fuller analysis of this phenomenon, along the lines described here.

Another aspect of Tigre morphology that is explained by the principle of the unidentified CV is the disappearance of geminates in the imperfective suffixed inflection, e.g. fa gg ər ‘leave.MSG’ vs. fa g ri ‘leave.FSG’. The base has four CV units fagøgørø, while the derived form seems to only have three: fagøri. With the principle of the unidentified CV, the form can have four CV units fagøCøri, with the final position governing the antepenultimate one across the penultimate one, thus allowing the latter to remain unidentified.

Recall that realization of the prefixal empty nucleus is avoided when possible in the dialect under discussion: Otherwise, one would in fact expect tə- to surface in all of the other forms discussed in this paper, and (33) to be realized as *təsʔal.

References

Bellem, Alex. 2007. Towards a comparative typology of emphatics: Across Semitic and into Arabic dialect phonology, PhD dissertation, University of London.

Benveniste, Emile. 1956. La nature des pronoms. In For Roman Jakobson, eds. Morris Halle, Horace G. Lunt, Hugh McLean, and Cornelis H. van Schooneveld, 34–37. The Hague: Mouton.

Bendjaballah, Sabrina, and Martin Haiden. 2008. A typology of emptiness in templates. In Sounds of silence: Empty elements in syntax and phonology, eds. Hartmann Jutta, Veronkia Hegedus, and Herman Claudius van Riemsdijk, 21–57. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bérces, Katalin B. 2006. What’s wrong with vowel-initial syllables? School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) Working Papers in Linguisticsa 14: 15–21.

Clements, George N., and Samuel Jay Keyser. 1983. CV phonology: A generative theory of the syllable. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Davis, Stuart. 2011. Geminates. In The Blackwell companion to phonology 2, eds. Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume, and Keren Rice, 837–859. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Elias, David L. 2005. Tigre of Habab: Short grammar and texts from the Rigbat people, PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Elihai, Yohanan. 2004. The olive tree dictionary: A transliterated dictionary of conversational Eastern Arabic (Palestinian). Jerusalem: Minerva.

Faust, Noam. 2014. Metathesis in Tigre imperatives. Phonology 31(2): 209–227.

Guerssel, Mohand, and Jean Lowenstamm. 1996. Ablaut in classical Arabic measure I active verbal forms. In Studies in Afroasiatic grammar, eds. Jacqueline Lecarme, Jean Lowenstamm, and Ur Shlonsky. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed Morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20: Essays in Linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Halle, Morris. 2003. Distributed Morphology: Impoverishment and Fission. In Research in Afroasiatic grammar: Afroasiatic languages 3, Sophia Antipolis, France 1996, eds. Jacqueline Lecarme, Jean Lowenstamm, and Ur Shlonsky, 125–150. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hayes, Bruce. 1989. Compensatory lengthening in moraic phonology. Linguistic Inquiry 20: 253–306.

Harbour, Daniel. 2009. On homophony and methodology in morphology. Morphology 18: 75–92.

Hopper, Paul J., and Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization. Cambridge textbooks in linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kraehenmann, Astrid. 2011. Initial geminates. In The Blackwell companion to phonology 2, eds. Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume, and Keren Rice, 1124–1145. Malden and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kaye, Jonathan, Jean Lowenstamm, and Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 1990. Constituent structure and government in phonology. Phonology Yearbook 7: 193–231.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 1982. Gemination and spirantization in Tigrinya. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 12(1): 103–122.

Kenstowicz, Michael. 1994. Phonology in generative grammar. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Leslau, Wolf. 1945. Short grammar of Tigré. Vol. 18 of Publications of the American Oriental Society, Offprint Series. New Haven: American Oriental Society.

Littmann, Enno. 1897. Die pronomina in Tigré. Zeitschrift für Assyrologie 12: 188–230. 291–316.

Littmann, Enno. 1898. Das verbum der Tigre-Sprache. Zeitschrift für Assyrologie 13: 133–178; 14: 1–102.

Littmann, Enno. Publications of the Princeton expedition to Abyssinia, 4 vols. Leyden. 1910–1915.

Larsen, Bergeton Uffe. 1998. Vowel length, raddoppiamento sintattico and the selection of the definite article in Italian. Langues et grammaire, 87–102. Paris: Université Paris 8.

Lowenstamm, Jean. 1996. CV as the only syllable type. In Current trends in phonology. Models and methods, eds. Jacques Durand and Bernard Laks. 419–441. Salford: ESRI

Lowenstamm, Jean. 1999. The beginning of a word. Phonologica 153–166. The Hague: Holland Academic Press.

Lowenstamm, Jean. 2003. Remarks on mutae cum liquida and branching onsets. In Living on the edge: 28 Papers in honor of Jonathan Kaye, ed. Stefan Ploch. Vol. 62 of Studies in Generative Grammar, 339–363. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Lowenstamm, Jean, and Jean-François Prunet. 1985. Tigre vowel harmonies. Paper presented at the 16th Annual Conference on African Linguistics, Yale University.

McCarthy, John J. 1981. A prosodic theory of non-concatenative morphology. Linguistic Inquiry 12: 373–418.

Morin, Yves-Charles. 1986. La loi de position ou de l’explication en phonologie historique. Revue Québécoise de Linguistique 15(2): 199–231.

Nakano, Aki’o, and Yoichi Tsuge. 1982. A vocabulary of Beni Amar dialect of Tigré. Tokyo: Institute for the study languages and cultures of Asia and Africa.

Palmer, Frank R. 1956. ‘Openness’ in Tigre: A problem in prosodic statement. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 18(3): 561–577.

Palmer, Frank R. 1962. The morphology of the Tigre noun. London: Oxford University Press.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993. Optimality Theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science Technical Report 2.

Raz, Shlomo. 1980. The morphology of the Tigre verb (Mansaʕ dialect). Journal of Semitic Studies 25(1): 66–84; 25(2): 205–238

Raz, Shlomo. 1983. Tigre grammar and texts. Malibu: Undena Publications.

Rose, Sharon. 2003. Triple Take: Tigre and the case of internal reduplication. San Diego Linguistic Papers 1: 109–128.

Scheer, Tobias. 1999. On constraints vs. non-circular approaches to word-initial clusters. Phonologica. 289–304. La Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

Scheer, Tobias. 2004. A lateral theory of phonology 1: What is CVCV, and why should it be? Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Scheer, Tobias, and Péter Szigetvári. 2005. Unified representations for the syllable and stress. Phonology 22: 37–75.

Voigt, Rainer. 2004. Der Wegfall der Personalelemente in den Präfixkonjugationen des Semitischen. In Studia aetiopica in honour of Siegbert Uhlig on the occasion of his 65th birthday, 345–354. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz.

Voigt, Rainer. 2009. Das Präsens im Tigre. Aethiopica 12: 155–163.

Walkaw, Martin. 2009. Person restrictions and the representation of third person: An argument from Barceloni Catalan. In Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’, Romance languages and linguistic theory, eds. Janine Berns, Haike Jacobs, and Tobias Scheer, 343–361. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Acknowledgements

I thank Mohammad for his time. For their help in funding the project, I also thank the Language, Logic and Cognition Center and my colleagues at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Edit Doron, Nora Boneh and Ivy Sichel. The data collected is available online at https://www.academia.edu/3615439/Tigre_Field_notes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Faust, N. Eroded prefixes, gemination and guttural effects in Tigre: An account in CVCV phonology. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 1209–1234 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9277-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9277-1