Abstract

Determining primate geographic ranges is essential for understanding their ecology and developing their conservation policies, but it is particularly challenging for rare, cryptic, or widely distributed species. Science-based methods and Indigenous and local knowledge have mutually contributed to addressing this conundrum. Here, we report on a new camera-trap record of a solitary mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) in Nki National Park, southeast Cameroon, and interviews with Baka people about encounters with mandrills. We placed 481 camera traps for 32,644 total days, obtaining one video of an adult male mandrill on 19 April 2021, 20.2 km north of the Dja River. We also interviewed 30 Baka people from two neighboring villages about their experiences of observing mandrills. Seven interviewees responded that they had observed mandrills in this area: three reported solitary males, and four reported large groups. All observations were in areas >30 km south of the villages and >20 years ago. The results suggest the presence, but also the rarity, of mandrills in this area, where only solitary males may range outside the species geographic distribution, possibly temporarily. However, we cannot conclude that large groups of mandrills are absent in this area because people are not allowed to stay in the park, so the Baka people’s knowledge of the remote areas has been severely limited. To determine the accurate distribution of primates and develop effective conservation actions, we need collaborative research and conservation platforms that further connect Indigenous and local people with scientists.

Résumé

La détermination des aires de répartition géographique des primates est essentielle pour comprendre leur écologie et élaborer des politiques de conservation, mais elle est particulièrement difficile pour les espèces rares, cryptiques ou largement répandues. Les méthodes scientifiques et les connaissances autochtones et locales ont mutuellement contribué à résoudre cette difficulté. Nous présentons ici un nouveau cas de mandrill solitaire (Mandrillus sphinx) enregistré à l'aide de caméra pièges dans le parc national de Nki, au sud-est du Cameroun, ainsi que des entretiens avec des Baka au sujet de leurs rencontres avec des mandrills. Nous avons placé 481 caméras pendant 32 644 jours au total, obtenant une vidéo d'un mandrill mâle adulte le 19 avril 2021, à 20,2 km au nord de la rivière Dja. Nous avons également interrogé 30 Baka de deux villages voisins sur leurs expériences d'observation des mandrills. Sept personnes interrogées ont répondu qu'elles avaient observé des mandrills dans cette zone : Trois ont rapporté des mâles solitaires, et quatre ont rapporté de grands groupes. Toutes les observations ont eu lieu dans des zones situées à plus de 30 km au sud des villages et il y a plus de 20 ans. Les résultats suggèrent la présence, mais aussi la rareté, des mandrills dans cette zone, où peut-être seuls les mâles solitaires quittent la distribution géographique de l'espèce, éventuellement de manière temporaire. Cependant, nous ne pouvons pas conclure que de grands groupes de mandrills sont absents de cette zone, car les gens ne sont pas autorisés à séjourner dans le parc, et les connaissances du peuple Baka sur les zones reculées ont donc été sévèrement limitées. Pour déterminer la distribution exacte des primates et développer des actions de conservation efficaces, nous avons besoin de plateformes collaboratives de recherche et conservation qui relient davantage les scientifiques et les populations autochtones et locales. *The publisher did not copy edit the abstract translation.

要旨

霊長類の地理的分布範囲を決定することは、種の生態について理解し、保全策を立案するために不可欠であるが、希少種、見つけにくい種、あるいは分布範囲が広い種については、特に困難である。これまでの研究において、この難題を解決するために科学的手法と在来・地域知とが相互に貢献してきた。本研究では、カメルーン東南部ンキ国立公園でのマンドリル (Mandrillus sphinx) の単独オス1頭の新たなカメラトラップ記録について報告するとともに、マンドリルとの遭遇に関する同地域のバカの人々へのインタビューについて報告する。私たちは計481台の自動撮影カメラをのべ32,644日間稼働させ、2021年4月19日に、ジャー川から北に20.2キロメートルの位置で、1頭のオトナオスのマンドリルのビデオ1ファイルを取得した。また、私たちは2つの近隣村に暮らす30名のバカに対し、マンドリルの観察経験について聞き取りをおこなった。その結果、7名がマンドリルを同地域で見たことがあると回答した(3名はヒトリオスの観察、4名は大きな群れの観察)。すべての観察は、村から30キロメートル以上南に離れた地域で20年以上前になされていた。これらの結果は、この地域にマンドリルが生息することを示唆しているが、同時にその希少性も示唆している。単独オスだけがこの種の地理的分布の外側を、おそらく一時的に遊動している可能性がある。しかしながら、群れがこの地域に存在していないと結論づけることはできない。なぜなら、国立公園内では宿泊が許されておらず、村から遠い場所に関するバカの知識は、とても限られているからである。霊長類の分布を正確に把握し、効果的な保全活動を展開するためには、先住民や地域住民と科学者とをさらに結びつけるような、共同研究・保全プラットフォームの設立が必要である。*The publisher did not copy edit the abstract translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How do we know where animals are present? Accurately identifying a species’ geographic range is an essential basis for understanding its ecology and developing policies for its conservation and management (Marsh et al., 2022). However, it is particularly challenging for some species, such as primates with cryptic features living in dense forests or with extensive ranges spanning multiple countries (Chen et al., 2023). To overcome this conundrum, primatologists and conservation scientists have employed various approaches to map species distributions.

Science-based methods for confirming a primate’s presence range from direct observations of individuals or calls (Schaffler & Kappeler, 2014) to genetic identification via fecal samples (Ferreira da Silva et al., 2020). Moreover, the scientific contribution has been boosted by the use of camera traps (Burton et al., 2015; Wevers et al., 2021). Particularly in forested areas, studies incorporating terrestrial and arboreal camera traps are flourishing (Cordier et al., 2022; Moore et al., 2021), and new evidence for the presence of elusive or rare primate species is increasingly reported (dos Santos-Filho et al., 2017; Lhota et al., 2012; Schaffler & Kappeler, 2014). The advantages of camera traps in range determination include the accuracy of records with exact time and place, and reliable species identification based on images; the drawbacks include the very narrow search range (~10 m in dense forests), the high costs, and great labor in fieldwork and analysis (Glover-Kapfer et al., 2019).

Primatologists have also long relied on the knowledge of Indigenous and local communities, who have broad experiences of animals on their lands. Indigenous and local knowledge remains vital in determining the geographic range of threatened primates and developing conservation plans (Estrada et al., 2022). For example, a nationwide survey of drills (Mandrillus leucophaeus) in Cameroon actively incorporated interviews with local hunters alongside field censuses by researchers to estimate the distribution and conservation status of this endangered primate (Morgan et al., 2013). Primatologists in Brazil interviewed local communities to update distribution maps of Maranhão red-handed howlers (Malouatta ululata) and information on their interactions with local people (Freire Filho et al., 2018). The inclusion of ethnographic interviews with local community members has benefits in providing a different perspective to the subject of research interest than that provided by quantitative datasets, thereby increasing the relevance of conclusions (Remis & Jost Robinson, 2017). Ethnographic surveys are also advantageous in that they can achieve broad coverage in a short time (Radhakrishna, 2017), provide the retrospective estimation of animal distribution based on the memory of local people (van Vliet et al., 2018), and incur comparatively low survey costs. Nevertheless, there are also potential challenges, including the ambiguity of the observation time and place, doubts about the reliability of species identification and accuracy of memory, and the need for a deep understanding of local languages and contexts (Ellwanger et al., 2017).

Mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) live in large groups of 300–850 animals (Abernethy et al., 2002; Hongo, 2014) in dense rainforests of Central West Africa. Group density is very low (White, 1994), as they travel long distances in large home ranges: the groups typically move 2–10 km per day (Hongo et al., 2022b; Hoshino, 1985; White et al., 2010), and a group living in the forest–savannah mosaic in Lopé National Park, Gabon, had a home range of 118 km2, of which 46 km2 was in forested areas (White et al., 2010). The poor visibility of rainforest habitats, low group densities, and high mobility make it extremely difficult to determine the presence and distribution of the species. However, conservation is urgently needed—this primate is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as “Vulnerable”, and its population size is considered to be declining, mainly due to hunting and habitat loss (Abernethy & Maisels, 2019).

The geographic range of mandrills has historically been determined using a combination of both qualitative and quantitative methods (Fig. 1). The distribution of mandrills was initially surveyed on the basis of field observations (Jouventin, 1975; Sabater Pi, 1971) and museum specimens (Grubb, 1973). A field survey in southeast Cameroon from 1988 to 1989 employed both direct observations by the researcher and interviews with local people, concluding that they occur only on the south bank of the Dja River (Mitani, 1990). These early studies helped delineate the first IUCN geographic range map (Oates & Butsynski, 2008). More recently, camera-trap surveys conducted outside their conventional distribution have found mandrills (Table I). These camera-trap observations expanded the distribution map (Abernethy & Maisels, 2019). Following this update, another camera-trap detection of a solitary male was reported on the east bank of the Ogooué River in eastern Gabon (Fonteyn et al., 2022).

Here, we report on a new camera-trap record of a solitary mandrill in Nki National Park on the north bank of the Dja River in southeast Cameroon. We also report on encounters with mandrills by the Baka people, an Indigenous ethnic group living in the surrounding area. The Baka in the northern periphery of Nki rely heavily on wildlife hunting and plant gathering for their livelihoods and culture, having inherited and reproduced a wealth of knowledge about their forests and animals (Hattori, 2006; Yasuoka, 2006a). Following the by-catch “discovery” of a camera trap, we conducted local interviews with Baka people to reinforce the image record with Indigenous knowledge. Recent studies have combined camera traps and local interviews to accurately determine the distribution of forest-living primates and other mammals, showing that interviews are particularly beneficial in accurately determining rare species (Alempijevic et al., 2021; Brittain et al., 2022a, 2022b; van Vliet et al., 2023). We aimed to draw comprehensive inferences about the presence of mandrills in this area by linking the two approaches.

Methods

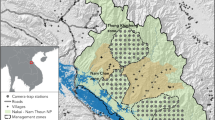

We carried out three camera-trap surveys between 2018 and 2021 in and around Nki and Boumba-Bek National Parks, East Region, Cameroon (Fig. 2). We originally designed all surveys to estimate the population densities of medium-sized terrestrial mammals hunted for meat, such as forest duikers and large rodents (Hongo et al., 2022a). Thus, systematic camera-placement designs were employed for all surveys, without placing cameras along animal trails and not using baits or lures. We used Browning® Strike Force HD series cameras (models BTC-5HDP and BTC-5HDPX) configured to record 10- or 20-s video footage in response to animal passage, with minimal intervals between the footage. The first survey was multi-layered, from September 2018 to February 2019 in three rectangular sites of 128 km2 each, with 88 terrestrial and 150 arboreal cameras deployed (Hongo et al., 2020). The second survey was over a large area, from December 2019 to April 2020, covering ca. 3400 km2 with 214 terrestrial cameras. The third survey, in which we found a solitary mandrill, was longer-term, from May 2019 to August 2021, employing 49 terrestrial cameras in a 49-km2 area of the Nki National Park. In total, 481 cameras—337 terrestrial and 144 arboreal cameras—were operational for at least one day. The total sampling effort was 32,644 camera days.

The first author conducted semi-structured interviews with the Baka people living in GB and ZB villages in August 2022 (Fig. 2). We chose these villages because the people there customarily use the large areas between the villages and the Dja River (Baka of Dimgba et al., 2021; Yasuoka, 2006b). The first author explained the research objectives to each interviewee and how the data would be used immediately before commencing the interview. All participants gave free, prior and informed consent—they knew that they could withdraw from participation at any time, and that their anonymity would be assured. We tried to conduct individual interviews as much as possible, but this artificial situation sometimes made interviewees uncomfortable. In such cases, we interviewed people in groups of two or three but asked for answers from each individual.

Interviews lasted 15–30 minutes in French and Baka languages, with the help of local assistants. We first asked about the interviewee’s personal information (name, gender, age, birthplace, and the time they came to the current village). Then, we showed the camera-trap footage of the solitary male recorded in this study and asked if they had seen a similar animal: “Est-ce que tu as déjà vu cet animal en forêt ? (Have you ever seen this animal in the forest?)”. If the interviewee answered yes, we then questioned them about the time of the last observation: “C’était quand ? (When was it?)”, “C’était de quelle saison ? (What season was it?)”, “sɔkɔ yaka ? sɔkɔ dùngà ? (Dry season? Rainy season?)”, “C’était quand tu étais encore petite ? (Was it when you were still a child?)”, “C’était avant que XX arrive à ce village pour la première fois, ou après ? (Was this before XX [name of a long-term researcher] arrived in the village for the first time, or after?)” We also asked about the location of the last observation, which we determined using river names: “Tu étais à coté de quelle rivière ? (What river were you by?)” To check the reliability of the responses, we further asked interviewees to describe the detailed context of the observation: “Qu’est-ce que tu étais en train de faire à ce moment-là ? (What were you doing at that time?)”, “Tu l’as vu avec qui ? (Who did you see it with?)” We also asked them to describe the morphology of the animals observed (size, color pattern, tail length) to see if they could describe the observed animal in detail. After completing all the questions about solitary males, we asked all interviewees about mandrill groups with the same interview procedure, using a video of a mandrill group recorded at another site.

After the interview, the first author gave each participant a small gift that cost around 250 CFA franc (chosen by the participant from candies, peanuts, and cigarettes). The gift items were chosen according to local customs; the gift quantity was determined so as not to be an undue incentive to participate or respond to the interviews.

Ethical note

This study complied with the laws of the Republic of Cameroon and was approved by the Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation (No. 0190/ MINRESI/Projet COMECA/PM/07/2018) and the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife (No. 1527/L/MINFOF/SETAT/SG/DFAP/SDCF/SEP/EP). Our interview survey was approved by the Center for African Area Studies, Kyoto University (No. 19-01B).

Data availability

Camera-trap data are not publicly available due to their use in future papers. However, the mandrill video is available on the Projet Coméca YouTube Channel (https://youtu.be/6gJxyDb_Ekc). The questionnaire sheet used for the interview survey and the anonymized dataset are in Supplementary Materials S1 and Supplementary S2 respectively.

Results

On 19 April 2021, at the start of the rainy season, a camera trap (at 2° 32′ 54″ N, 14° 46′ 22″ E) in the third survey recorded a mandrill moving on the ground (Fig. 3). The observation was made 20.2 km north of the Dja River, southwest of the confluence of the Jalope and Bek Rivers. We estimated it to be an adult male of > 9 years old from its fully-grown body size and morphological traits of its body and rump (Setchell & Dixson, 2002). This is the only camera-trap record of the mandrill in the study area, and no groups were recorded.

In total, 30 Baka adults participated in the interviews (Table II). Based on their responses, we evaluated the responses of 29 out of the 30 participants as being reliable. The 29 interviewees understood the meaning of our questions correctly, described the observed situations and morphology of the animals observed in detail, and did not confuse mandrills with other similar-looking species, such as agile mangabeys (Cercocebus agilis). Answers from the remaining interviewee were vague in their description of the mandrill morphology, so we excluded them from further analysis.

Of the 29 interviewees, seven (24%) reported having observed mandrills in this area. Their observations were all made in areas > 30 km from the villages, near the Bek or Jalope Rivers (Fig. 2). The ability of the interviewees to confirm the mandrill’s current presence was likely to be limited by park regulations prohibiting people from staying within this area.

Two Baka interviewees in GB village (from the same interview group) and one in ZB village reported observations of solitary male mandrills. A female interviewee at GB said that her late spouse had hunted a solitary male 30–40 years ago near the Bek River. The only observer in ZB said he had only seen a male once near the Jalope River during the dry season, about 20 years ago.

Four Baka people from three different interview groups in GB reported having observed large groups of mandrills in the study area; no one at ZB reported seeing groups. All observations of large groups were made > 20 years ago near the Bek River, and two observers from separate interview groups stated that they had seen large groups of mandrills on the north bank of the Bek River 30 to 40 years ago.

Discussion

Our camera traps in Nki National Park recorded an adult male mandrill, demonstrating the presence of this Vulnerable primate on the north bank of the Dja River, which falls outside the current IUCN range of this species. Interviews with neighbouring Baka people also suggested the historical presence of mandrills in the same area.

Our results reveal the rarity, as well as the presence, of mandrills in the area: 481 camera traps working 32,644 days in total recorded only one adult male; less than one-fourth of Baka interviewees reported having seen mandrills in the area. Recent camera-trap observations in other areas outside the 2008 version of the IUCN distribution map have also recorded mostly adult or subadult males; groups have only been observed in the northwest of the Republic of Congo (Table I). These reports, including the present one, suggest that solitary males travel outside the geographic range of large groups, perhaps temporarily. In contrast to females, which form large groups throughout the year, many male mandrills live in groups only during the mating season and move alone during the rest of the year (Abernethy et al., 2002; Brockmeyer et al., 2015; Hongo et al., 2016). It would, therefore, be more relevant to determine geographic ranges for males and females separately than to create a single distribution map for both sexes, particularly for widely-ranging primates such as mandrills. Sex-specific geographic maps would also benefit conservation planning and are proposed in an upcoming IUCN Action Plan (Dempsey et al., (in press)).

In contrast to solitary males, whose presence was confirmed by both camera traps and Baka interviewees, the presence of mixed-sex groups was not shown by camera traps but was reported by four interviewees in three separate interview groups. All observers report that the last observation was > 20 years ago, which may suggest that mandrills have declined in the study area in recent years. However, it would be premature to suggest the recent disappearance of mandrills in the area from our results. Human activities within Nki National Park have been strictly limited since its creation in 2005 (Hattori, 2014), so the Baka’s knowledge about remote parts of the park has probably been updated less regularly since then than previously. Therefore, we cannot conclude as to whether the geographic range of mixed-sex groups has shrunk recently or whether groups are still present in the study area but are too low in density to be detected by our camera traps.

Our study shows the effectiveness of the integration of camera trapping and local interviews in examining the presence of an elusive animal. Video images from the camera traps were decisively helpful for unambiguous communications between researchers and the Baka people, which might have been more difficult with photos and illustrations alone. Also, we have learned from local people about the basics of the Baka language, the names and locations of rivers, and past events in the study villages prior to this study, which helped us to determine the location and time of the Baka interviewees’ past observations. Locally based methods such as our study contribute to sharing the capacity between local people and non-local researchers (Camino et al., 2020) and illustrate the importance of exchanging knowledge in wildlife conservation (Copete et al., 2023; Haris et al., 2024). To make knowledge of primate distribution more accurate and their conservation actions more relevant to local conditions, we need collaborative research and conservation platforms that further connect Indigenous and local people with scientists.

References

Abernethy, K., & Maisels, F. (2019). Mandrillus sphinx. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019, e.T12754A17952325. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T12754A17952325.en

Abernethy, K. A., White, L. J. T., & Wickings, E. J. (2002). Hordes of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx): Extreme group size and seasonal male presence. Journal of Zoology, 258(1), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0952836902001267

Alempijevic, D., Hart, J. A., Hart, T. B., & Detwiler, K. M. (2021). Using local knowledge and camera traps to investigate occurrence and habitat preference of an Endangered primate: The endemic dryas monkey in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Oryx, 56(2), 260–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0030605320000575

Allam, A., N’Goran, K. P., Mahoungou, S., & Ikoa, B. (2016). Rapport d’inventaire des grands et moyens mammifères dans la forêt de Djoua-Ivindo. WWF GCPO-MEFDD.

Baka of Dimgba, Hirai, M., Kamgaing, T. O. W., & Meldrum, G. (2021). Hunting, gathering and food sharing in Africa’s rainforests: The forest-based food system of the Baka Indigenous People in South-eastern Cameroon. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Alliance of Bioversity International & CIAT (Eds.), Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: Insights on sustainability and resilience from the front line of climate change (pp. 72–94). FAO, Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT. https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b4f735d8-7008-423c-b28a-300ab920c241/content/src/html/sec1_0.html, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb5131en

Brittain, S., Rowcliffe, M., Earle, S., Kentatchime, F., Kamogne Tagne, C. T., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2022a). Power to the people: Analysis of occupancy models informed by local knowledge. Conservation Science and Practice, 4(8), e12753. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12753

Brittain, S., Rowcliffe, M. J., Kentatchime, F., Tudge, S. J., Kamogne-Tagne, C. T., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2022b). Comparing interview methods with camera trap data to inform occupancy models of hunted mammals in forest habitats. Conservation Science and Practice, 4(4), e12637. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12637

Brockmeyer, T., Kappeler, P. M., Willaume, E., Benoit, L., Mboumba, S., & Charpentier, M. J. (2015). Social organization and space use of a wild mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) group. American Journal of Primatology, 77(10), 1036–1048. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.22439

Burton, A. C., Neilson, E., Moreira, D., Ladle, A., Steenweg, R., Fisher, J. T., Bayne, E., & Boutin, S. (2015). Wildlife camera trapping: A review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(3), 675–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12432

Camino, M., Thompson, J., Andrade, L., Cortez, S., Matteucci, S. D., & Altrichter, M. (2020). Using local ecological knowledge to improve large terrestrial mammal surveys, build local capacity and increase conservation opportunities. Biological Conservation, 244, 108450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108450

Chen, C., Granados, A., Brodie, J. F., Kays, R., Davies, T. J., Liu, R., Fisher, J. T., Ahumada, J., McShea, W., Sheil, D., Mohd-Azlan, J., Agwanda, B., Andrianarisoa, M. H., Appleton, R. D., Bitariho, R., Espinosa, S., Grigione, M. M., Helgen, K. M., Hubbard, A., … Burton, A. C. (2023). Combining camera trap surveys and IUCN range maps to improve knowledge of species distributions. Conservation Biology, 38(3), e14221. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.14221

Copete, J. C., Kik, A., Novotny, V., & Cámara-Leret, R. (2023). The importance of Indigenous and local people for cataloging biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 38(12), 1112–1114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2023.08.017

Cordier, C. P., Ehlers Smith, D. A., Ehlers Smith, Y., & Downs, C. T. (2022). Camera trap research in Africa: A systematic review to show trends in wildlife monitoring and its value as a research tool. Global Ecology and Conservation, 40, e02326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2022.e02326

Dempsey, A., Fernnández, D., McCabe, G., Abernethy, K., Abwe, E. E., Gonadelé Bi, S., Kivai, S. M., Maisels, F., Matsuda Goodwin, R., McGraw, W. S., McLester, E., ter Meulen, T., Oates, J. F., Paddock, C. L., & Savvantoglou, A. (in press). Cercocebus and Mandrillus conservation action plan 2023–2027. IUCN.

dos Santos-Filho, M., Bernardo, C. S. S., Van der Laan Barbosa, H. W., Gusmao, A. C., Jerusalinsky, L., & Canale, G. R. (2017). A new distribution range of Ateles chamek (Humboldt 1812) in an ecotone of three biomes in the Paraguay River Basin. Primates, 58(3), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-017-0601-3

Ellwanger, A. L., Riley, E. P., Niu, K., & Tan, C. L. (2017). Using a mixed-methods approach to elucidate the conservation implications of the human-primate interface in Fanjingshan National Nature Reserve, China. In K. M. Dore, E. P. Riley, & A. Fuentes (Eds.), Ethnoprimatology: A practical guide to research at the human-nonhuman primate interface (pp. 257–270). Cambridge University Press.

Estrada, A., Garber, P. A., Gouveia, S., Fernandez-Llamazares, A., Ascensao, F., Fuentes, A., Garnett, S. T., Shaffer, C., Bicca-Marques, J., Fa, J. E., Hockings, K., Shanee, S., Johnson, S., Shepard, G. H., Shanee, N., Golden, C. D., Cardenas-Navarrete, A., Levey, D. R., Boonratana, R., … Volampeno, S. (2022). Global importance of Indigenous Peoples, their lands, and knowledge systems for saving the world’s primates from extinction. Science Advances, 8(32), 2927. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn2927

Ferreira da Silva, M. J., Paddock, C., Gerini, F., Borges, F., Aleixo-Pais, I., Costa, M., Colmonero-Costeira, I., Casanova, C., Lecoq, M., Silva, C., Bruford, M. W., Varanda, J., & Minhos, T. (2020). Chasing a ghost: Notes on the present distribution and conservation of the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys) in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Primates, 61(3), 357–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-020-00817-2

Fonteyn, D., Fayolle, A., Orbell, C., Malignat, R., Cornélis, D., Vanthomme, H., Vigneron, P., & Vermeulen, C. (2022). Range extension of the agile mangabey (Cercocebus agilis) and of the mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) in eastern Gabon evidenced by camera traps. African Journal of Ecology, 60(4), 1267–1270. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.13061

Freire Filho, R. G., Pinto, T., & Bezerra, B. M. (2018). Using local ecological knowledge to access the distribution of the Endangered Caatinga howler monkey (Alouatta ululata). Ethnobiology and Conservation, 7, 10. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2018-08-7.10-1-22

Glover-Kapfer, P., Soto-Navarro, C. A., Wearn, O. R., Rowcliffe, M., & Sollmann, R. (2019). Camera-trapping version 3.0: Current constraints and future priorities for development. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 5(3), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.106

Grubb, P. (1973). Distribution, divergence and speciation of the drill and mandrill. Folia Primatologica, 20(2–3), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1159/000155574

Haris, H., Othman, N., Kaviarasu, M., Najmuddin, M. F., Abdullah-Fauzi, N. A. F., Ramli, F. F., Sariyati, N. H., Ilham-Norhakim, M. L., Md-Zain, B. M., & Abdul-Latiff, M. A. B. (2024). Ethnoprimatology reveals new extended distribution of critically endangered banded langur Presbytis femoralis (Martin, 1838) in Pahang, Malaysia: Insights from indigenous traditional knowledge and molecular analysis. American Journal of Primatology, e23631. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23631

Hattori, S. (2006). Utilization of Marantaceae plants by the Baka hunter–gatherers in southeastern Cameroon. African Study Monographs, Suppl., 33, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.14989/68476

Hattori, S. (2014). Current issues facing the forest people in southeastern Cameroon: The dynamics of Baka life and their ethnic relationship with farmers. African Study Monographs, Suppl., 47, 97–119. https://doi.org/10.14989/185099

Hedwig, D., Kienast, I., Bonnet, M., Curran, B. K., Courage, A., Boesch, C., Kühl, H. S., & King, T. (2018). A camera trap assessment of the forest mammal community within the transitional savannah–forest mosaic of the Batéké Plateau National Park, Gabon. African Journal of Ecology, 56(4), 777–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12497

Hongo, S. (2014). New evidence from observations of progressions of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx): A multilevel or non-nested society? Primates, 55(4), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-014-0438-y

Hongo, S., Nakashima, Y., Akomo-Okoue, E. F., & Mindonga-Nguelet, F. L. (2016). Female reproductive seasonality and male influxes in wild mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx). International Journal of Primatology, 37(3), 416–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-016-9909-x

Hongo, S., Dzefack, Z. C. B., Vernyuy, L. N., Minami, S., Nakashima, Y., Djiéto-Lordon, C., & Yasuoka, H. (2020). Use of multi-layer camera trapping to inventory mammals in rainforests in southeast Cameroon. African Study Monographs, Suppl., 60, 21–37. https://doi.org/10.14989/250126

Hongo, S., Dzefack, Z. C. B., Vernyuy, L. N., Minami, S., Mizuno, K., Otsuka, R., Hiroshima, Y., Djiéto-Lordon, C., Nakashima, Y., & Yasuoka, H. (2022a). Predicting bushmeat biomass from species composition captured by camera traps: Implications for locally based wildlife monitoring. Journal of Applied Ecology, 59(10), 2567–2580. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14257

Hongo, S., Nakashima, Y., Akomo-Okoue, E. F., & Mindonga-Nguelet, F. L. (2022b). Seasonality in daily movement patterns of mandrills revealed by combining direct tracking and camera traps. Journal of Mammalogy, 103(1), 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmammal/gyab141

Hoshino, J. (1985). Feeding ecology of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) in Campo Animal Reserve, Cameroon. Primates, 26(3), 248–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02382401

Jouventin, P. (1975). Observations sur la socio-écologie du mandrill. La Terre et La Vie, 4, 493–532.

Lhota, S., Loken, B., Spehar, S., Fell, E., Pospech, A., & Kasyanto, N. (2012). Discovery of Miller’s grizzled langur (Presbytis hosei canicrus) in Wehea Forest confirms the continued existence and extends known geographical range of an endangered primate. American Journal of Primatology, 74(3), 193–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.21983

Marsh, C. J., Sica, Y. V., Burgin, C. J., Dorman, W. A., Anderson, R. C., Del Toro Mijares, I., Vigneron, J. G., Barve, V., Dombrowik, V. L., Duong, M., Guralnick, R., Hart, J. A., Maypole, J. K., McCall, K., Ranipeta, A., Schuerkmann, A., Torselli, M. A., Lacher, T., Jr., Mittermeier, R. A., … Jetz, W. (2022). Expert range maps of global mammal distributions harmonised to three taxonomic authorities. Journal of Biogeography, 49(5), 979–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14330

Mitani, M. (1990). A note on the present situation of the primate fauna found from south-eastern Cameroon to northern Congo. Primates, 31(4), 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02382549

Moore, J. F., Soanes, K., Balbuena, D., Beirne, C., Bowler, M., Carrasco-Rueda, F., Cheyne, S. M., Coutant, O., Forget, P. M., Haysom, J. K., Houlihan, P. R., Olson, E. R., Lindshield, S., Martin, J., Tobler, M., Whitworth, A., & Gregory, T. (2021). The potential and practice of arboreal camera trapping. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 12(10), 1768–1779. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.13666

Morgan, B. J., Abwe, E. E., Dixson, A. F., & Astaras, C. (2013). The distribution, status, and conservation outlook of the drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus) in Cameroon. International Journal of Primatology, 34(2), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-013-9661-4

Ngo Bata, M., Easton, J., Fankem, O., Wacher, T., Tom, B., Eliseé, T., Taguieteu, P. A., & Olson, D. (2017). Extending the northeastern distribution of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) into the Dja Faunal Reserve, Cameroon. African Primates, 12, 65–67.

Oates, J. F., & Butsynski, T. M. (2008). Mandrillus sphinx. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2008, e.T12754A3377579. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T12754A3377579.en

Radhakrishna, S. (2017). Culture, conflict, and conservation: Living with nonhuman primates in northeastern India. In K. M. Dore, E. P. Riley, & A. Fuentes (Eds.), Ethnoprimatology: A practical guide to research at the human-nonhuman primate interface (pp. 271–283). Cambridge University Press.

Remis, M. J., & Jost Robinson, C. A. (2017). Nonhuman primates and “others” in the Dzanga Sangha Reserve: The role of anthropology and multispecies approaches in ethnoprimatology. In K. M. Dore, E. P. Riley, & A. Fuentes (Eds.), Ethnoprimatology: A practical guide to research at the human-nonhuman primate interface (pp. 190–205). Cambridge University Press.

Sabater Pi, J. (1971). Contribución a la ecología de los “Mandrillus Sphinx (Linnaeus) 1758" de río Muni (República de Guinea Ecuatorial). Miscelánea Zoológica, 3(1), 85–100.

Schaffler, L., & Kappeler, P. M. (2014). Distribution and abundance of the world’s smallest primate, Microcebus berthae, in central western Madagascar. International Journal of Primatology, 35(2), 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-014-9768-2

Setchell, J. M., & Dixson, A. F. (2002). Developmental variables and dominance rank in adolescent male mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx). American Journal of Primatology, 56(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.1060

van Vliet, N., Muhindo, J., Kambale Nyumu, J., Mushagalusa, O., & Nasi, R. (2018). Mammal depletion processes as evidenced from spatially explicit and temporal local ecological knowledge. Tropical Conservation Science, 11, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940082918799494

van Vliet, N., Rovero, F., Muhindo, J., Nyumu, J., Mbangale, E., Nziavake, S., Cerutti, P., Nasi, R., & Quintero, S. (2023). Comparison of local ecological knowledge versus camera trapping to establish terrestrial wildlife baselines in community hunting territories within the Yangambi landscape in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ethnobiology and Conservation, 12, 19. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2023-09-12.19-1-14

Wevers, J., Beenaerts, N., Casaer, J., Zimmermann, F., Artois, T., Fattebert, J., Rowcliffe, M., & Sollmann, R. (2021). Modelling species distribution from camera trap by-catch using a scale-optimized occupancy approach. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation, 7(3), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.207

White, L. J. T. (1994). Biomass of rain forest mammals in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. Journal of Animal Ecology, 63(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/5217

White, E. C., Dikangadissi, J.-T., Dimoto, E., Karesh, W. B., Kock, M. D., Ona Abiaga, N., Starkey, R., Ukizintambara, T., White, L. J. T., & Abernethy, K. A. (2010). Home-range use by a large horde of wild Mandrillus sphinx. International Journal of Primatology, 31(4), 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-010-9417-3

Yasuoka, H. (2006a). Long-term foraging expeditions (Molongo) among the Baka hunter–gatherers in the northwestern Congo Basin, with special reference to the “wild yam question.” Human Ecology, 34(2), 275–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-006-9017-1

Yasuoka, H. (2006b). The sustainability of duiker (Cephalophus spp.) hunting for the Baka hunter–gatherers in southeastern Cameroon. African Study Monographs, Suppl., 33, 95–120. https://doi.org/10.14989/68473

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the wholehearted help of the Coméca Project staff, especially Timothée S. Kamgaing and Alidou Lytti, and the warm cooperation of the local people in the study area. Anthelme Allam kindly shared with us the information he had personally observed. Our gratitude also goes to Carolyn Jost Robinson and four anonymous reviewers, who provided many constructive comments and suggestions to the earlier versions of the manuscript. This study is a product of the Coméca Project (JPMJSA1702), supported by the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (SATREPS) in collaboration between the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). It was also supported by the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN), Japan (Project No. RIHN14210169).

Funding

This study was funded by the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Japan International Cooperation Agency as a program of the Science and Technology Research Partnership for Sustainable Development (JST/JICA, SATREPS, grant number JPMJSA1702) and by the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (Project No. RIHN14210169).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH, HY and CD-L conceived the study. ZCBD, VVMD, MANA, HY and SH conducted camera-trap surveys. SH carried out the interviews. KM, YH and SH analyzed the camera trap videos. SH wrote the manuscript, and the other authors provided editorial advice.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Inclusion and Diversity Statement

While citing references scientifically relevant to this work, we also actively worked to promote gender balance in our reference list. The author list includes contributors from the country where the research was conducted and who participated in study design and data collection.

Conflict interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Carolyn A. Jost Robinson

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hongo, S., Dzefack, Z.C.B., Mopo Diesse, V.V. et al. Mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) Presence in Southeast Cameroon Confirmed By Camera Traps and Indigenous Knowledge. Int J Primatol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-024-00451-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-024-00451-5