Abstract

While warming and eutrophication have increased the frequency and magnitude of harmful cyanobacterial blooms globally, the scenario for many eutrophic tropical freshwaters is a perennial year-round bloom. Yet, the drivers of persistent blooms are less understood when conditions such as light, temperature, and nutrients favor cyanobacteria growth year-round, and especially in regions facing recurrent periods of drought. In order to understand the drivers of cyanobacteria dominance, we assessed the abiotic conditions related to the abundance and dominance of the two dominant bloom-forming genera Raphidiopsis and Microcystis, in six shallow, man-made lakes located in the semiarid Northeastern region of Brazil during a prolonged regional drought. Lower water level corresponded to increased phosphorous and nitrogen concentration and, consequently, phytoplankton biomass. Cyanobacterial biomass was also proportional to phosphorus concentrations during year-round blooms. Yet, the two dominant cyanobacterial genera, Raphidiopsis and Microcystis, seldom co-occurred temporally and the switch between them was driven by water transparency. Our results illustrate the effects of drought induced water level reductions on the biomass and composition of cyanobacterial blooms in tropical shallow man-made lakes. Given the ideal year-round conditions (i.e., high light and temperature), droughts may be expected to intensify the risk and multitude of problems associated with eutrophication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The link between harmful cyanobacterial blooms and eutrophication has long been recognized as a critical threat to freshwater ecosystems (Paerl, 1988). Cyanobacteria blooms alter energy flux in aquatic food webs, leading to loss of biodiversity and threatening the sustainability of aquatic ecosystems (Paerl & Otten, 2013). Eutrophication and high cyanobacteria biomass affect many ecosystem services, promoting significant economic losses, including the increase in water treatment cost for drinking supply, decline of commercial and subsistence fishing and aquaculture, and impairment of recreational use of freshwaters (Aylward et al., 2005; EPA, 2015; Le Moal et al., 2019). Furthermore, the increase of organic matter caused via blooms promote trihalomethanes (THM) formation, when chlorination is applied for disinfection purposes of drinking supply, which are environmental pollutants and potentially carcinogenic (Rook, 1974; Gallard & Von Gunten, 2002). Moreover, the production of cyanotoxins poses a potential health hazard for pets, livestock, wildlife, and also humans, especially when drinking water supplies are affected (Carmichael, 1992; Merel et al., 2013; Paerl, 2018).

The observed enhancement of blooms in terms of distribution, frequency, and magnitude is a consequence of the combined and even interactive effects of eutrophication and climate change, including warming (Paerl & Huisman, 2008; Burford et al., 2016; Harke et al., 2016; Paerl & Otten, 2016; Paerl, 2017; Salmaso et al., 2018). High dominance and biomass of cyanobacteria in freshwaters are triggered by combined abiotic and biotic drivers such as anthropogenic nutrient over-enrichment, namely from excessive loads of phosphorus and nitrogen, high temperatures and light intensity, shallow depth, low flushing, high inorganic turbidity, and weak grazing pressure (Soares et al., 2009; Moss, 2011; Rigosi et al., 2014; Costa et al., 2016; Paerl, 2017; Leitão et al., 2018; González-Madina et al., 2019; Havens et al., 2019; Amorim et al., 2020). There also is an effect of temperature and solar irradiance on the susceptibility of shallow lakes to develop blooms for a given nutrient concentration (Kosten et al., 2012).

In tropical latitudes, cyanobacterial blooms in shallow eutrophic waters are more frequent and last longer when compared to their higher latitude counterparts, where key drivers such as light and temperature fluctuate seasonally (Lind et al., 2016). Indeed, in the absence of such seasonality, blooms often persist year-round in eutrophic waters (Figueredo & Giani, 2009; Figueredo et al., 2016; Batista et al., 2018; Giani et al., 2020). Yet, factors regulating cyanobacterial biomass and community composition during persistent blooms are less understood, which is, at least partly, because most information on blooms is from regions where such phenomena are seasonal (McGregor & Fabbro, 2000; Soares et al., 2009; Muir & Perissinotto, 2011; Lind et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2016; Batista et al., 2018).

Seasonal droughts also play a major role in cyanobacteria bloom dynamics (Naselli-Flores, 2003; Medeiros et al., 2015; Brasil et al., 2016; Costa et al., 2019; Tilahun & Kifle, 2019). The lack of precipitation during droughts reduces lake depth and subsequently affects multiple physical, chemical, and biological conditions (Naselli-Flores, 2003; Olds et al., 2011; Mosley, 2015). The abiotic effects resulting from droughts have been reported to favor cyanobacteria dominance (McGregor & Fabbro, 2000; Bouvy et al., 2003; Brasil et al., 2016). Conversely, periods of extreme prolonged drought in shallow lakes may also limit cyanobacteria due to high inorganic turbidity, in favor of mixotrophic organisms or diatoms (Costa et al., 2016, 2019; Crossetti et al., 2019). Hence, while there is little doubt that droughts result in a general decline in water quality, the impacts of drought on bloom dynamics are variable and likely lake-specific. Overall, the role of drought induced water level reduction on the dynamics of persistent year-round blooms is poorly understood.

Successful water quality management depends on identifying the local drivers of the cyanobacterial assemblage for a given lake (Mantzouki et al., 2016; Paerl, 2017; Moura et al., 2018; Le Moal et al., 2019). Despite several shared traits among genera, cyanobacteria are a heterogeneous group responding differently to environmental conditions and abiotic regulators. Therefore, understanding the link between key traits and environmental regulators is essential to develop specific management actions to improve water quality (Mantzouki et al., 2016). For instance, toxigenic colonial Microcystis and filamentous Raphidiopsis are the main known genera to form blooms in tropical waters (Soares et al., 2013; Brasil et al., 2016; Tilahun & Kifle, 2019). These genera produce distinct toxins with implications for water quality, Microcystis mostly produces the hepatotoxin microcystin, while Raphidiopsis may synthesize a diverse array of neurotoxins such as saxitoxin, neosaxitoxin, and gonyautoxins in addition to cytotoxic cylindrospermopsin (Sukenik et al., 2012; Cirés et al., 2017). Higher diversity of potential toxin classes during Raphidiopsis blooms may increase management costs (i.e., toxin analysis and water treatment) of this genus compared to Microcystis (Paerl & Otten, 2016).

Each cyanobacteria genus shows specific ecophysiological traits that represent adaptations to distinct environmental conditions (Dokulil & Teubner, 2000; Mantzouki et al., 2016). Although both Microcystis and Raphidiopsis have been associated with eutrophic waterbodies (Soares et al., 2013), they have different environmental preferences. Raphidiopsis is a shade-tolerant species that dominates during dry periods and under low light availability in warm, mixed, and shallow environments (Padisák, 1997; Reynolds et al., 2002; Soares et al., 2009, 2013; Costa et al., 2019). In contrast, buoyant Microcystis is adapted to higher light intensity (Paerl et al., 1985; Soares et al., 2009; Torres et al., 2016), low turbulence (Huisman et al., 2004), and stratified environments (Soares et al., 2013). Moreover, Raphidiopsis (potential N2 fixer) might be expected to dominate when nitrogen is limiting, while Microcystis (non-N2 fixer) is expected to dominate when nitrogen is not limiting growth (Schindler et al., 2008; Paterson et al., 2011; Mowe et al., 2015). Although eutrophic conditions stimulate both genera, Raphidiopsis blooms are more common under higher nutrient concentrations, especially phosphorus (Soares et al., 2013; Bonilla et al., 2016). Yet, few studies have reported on the abiotic regulators of tropical and truly year-round blooms (Mowe et al., 2015).

Here, we aimed at identifying environmental factors related to the temporal variability of phytoplankton abundance, community composition, and cyanobacterial dominance in six shallow man-made multi-use lakes in the Brazilian semiarid tropical region during a prolonged drought. We hypothesized that (i) low water level will correspond to increased nutrient, phytoplankton, and cyanobacterial biomass concentration, and (ii) the composition of year-round cyanobacterial blooms will change with euphotic depth. We discuss the implications of the results for multiple uses of semiarid man-made lakes in tropical climates with perennial blooms.

Material and methods

Study site

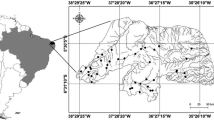

We studied six lakes located in the northeast region of Brazil (Fig. 1), where the regional climate is tropical Semiarid (BS’h’, Alvares et al. 2013), characterized by low annual rainfall (average rainfall of 550 mm/year), high average annual temperature (~ 26.5°C), and evapotranspiration rates above 1500 mm year−1 (Menezes et al., 2012; Braga et al., 2015). Rainfall is concentrated in a few months, usually from February to May (i.e., the rainy season), while the other months are characterized by negative water balance representing the drought season (Marengo et al., 2017). Drought is a natural phenomenon in this region; however, the intensity and duration of dry periods have been increasing (Marengo et al., 2020). The most recent drought lasted from 2012 until mid-2018, and represented one of the longest droughts in the Brazilian semiarid region in the last decades (Marengo et al., 2018). This prolonged drought varied from moderately to extremely dry before our sampling, according to the Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) (Figueiredo & Becker, 2018; Braga & Becker, 2020; Marengo et al., 2020), with rainfall anomalies between 20 and 60% below the 1981–2000 mean. During this period, 2012 and 2016 were the driest years with rainfall 300–400 mm year−1 below the expected amount (Marengo et al., 2018). Hence, we sampled lakes with relatively low water volume during this drought period in 2017, i.e., three of them had their volume between 11 and 33% of its maximum capacity (Table 1).

The morphometric variables, area, and maximum capacity of the lakes were obtained from the State Department of Environment and Water Resources (SEMARH, 2017) (Table 1). The studied lakes have been used for multiple purposes, including irrigation, fishing, leisure activities, livestock maintenance and, two of them, Santa Cruz do Apodi (Sta. Cruz) and Boqueirão de Parelhas (Boq. Parelhas), also for drinking water supply. This study was conducted as part of a monthly monitoring program (12 months) designed to evaluate whether such lakes may be suitably used for fish cage culture. These lakes match the scenario described to favor cyanobacteria populations: warm temperatures, high solar irradiance, and high vulnerability to nutrient input, especially from diffuse anthropic sources and internal fertilization from sediments (Kosten et al., 2011; Cavalcante et al., 2018).

Sampling and analysis

Water samplings from the six lakes were carried out on two consecutive days at monthly intervals from January to December 2017. The sampling point was set in the deepest part of each lake near the dam. The mean of three depth measurements at the sampling point was used as a proxy for maximum depth (Zmax). Water transparency was assessed using a Secchi disk. The euphotic depth (Zeu) was calculated as 2.7 times the Secchi transparency (Cole, 1994). Water temperature was measured in situ at the bottom and top of the water column. Water samples were collected with a PVC tube in each lake (2 m in length) integrating the first two meters of the water column beneath the surface. This procedure was repeated five times spaced around the collecting point with ~ 2 m horizontal distance between them. Water samples (~ 30 l/sample) were integrated and stored into pre-washed bottles. Phytoplankton samples were immediately fixed with acetic Lugol solution. Samples for chemical analyses were transported to the laboratory in a refrigerated cooler box.

Aliquots of unfiltered lake water were stored in a freezer (− 20°C) for total phosphorus (TP) and total nitrogen analyses (TN). For chlorophyll-a (Chl-a), total dissolved nitrogen (TDN) and total dissolved phosphorus (TDP), total suspended solids (TSS), volatile suspended solids (VSS—Organic), and fixed suspended solids (FSS—Inorganic), aliquots of water (250–500 ml) were filtered onto GF/C glass fiber filters (1.2 μm pore size). TN and TDN were analyzed by standard techniques using SHIMADZU TOCVCPN sampler with the SSM-5000A solid sample combustion unit by chemiluminescence. TP and TDP were determined using the persulfate oxidation method (Valderrama, 1981). Chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) was quantified by spectrophotometry using ethanol 95% as a solvent (Wintermans & De Mots, 1965; Jespersen & Christoffersen, 1987), while TSS, VSS, and FSS were determined using gravimetric analyses (Chanlett, 1947). To assess the trophic states of the lakes, we used the criteria proposed by Thornton & Rast (1993). According to these authors, waters of semiarid lakes with total phosphorus (TP) concentrations lower than 50 μg l−1 and total chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) lower than 15 μg l−1 may be classified as mesotrophic while those samples with TP and Chl-a higher than 50 μg l−1 and 15 μg l−1, respectively, may be considered as eutrophic.

The identification and quantification of phytoplankton community was performed with an optic light and inverted microscope (× 400 magnification), until species level (or the lowest taxonomic level possible) via morphologic and morphometric characteristics. The individuals (cells, colonies, and filaments) were enumerated in random fields (Uhelinger, 1964), using the sedimentation technique (Utermöhl, 1958). At least 100 specimens of the most frequent species (P < 0.05; Lund et al., 1958) were counted. The volume of the sedimentation chamber was selected depending on the amount of algae and/or detritus in the sample. The biovolume (mm3 l−1) of phytoplankton was obtained based on approximated geometric forms (Hillebrand, 1999; Fonseca et al., 2014) after counting 40–60 specimens. Phytoplankton biomass (mg l−1) was calculated by assuming that the unit of fresh weight is equivalent to a mass of 1 mm3 l−1 = 1 mg l−1 (Wetzel & Likens, 2000). Species representing more than 5% of the total biomass were included in the statistical analyses. The estimation of mean cell size was based on measurements of at least 40 cells or individuals (case of Raphidiopsis). In the case of cyanobacteria species with dense colonies such as Microcystis (except M. protocystis), biovolume was calculated according to Fonseca et al., (2014), which uses a conversion factor to consider the free space between cells as a taxonomic characteristic of each species. In general, geometric shapes such as sphere, spheroid, ellipsoid, or a combination there of were used, while considering three different categories about colony size, small, medium, and large based on their greatest axis linear dimension, as detailed further in Fonseca et al., (2014).

We considered a species or genus dominant if its relative biomass was > 50% of the total phytoplankton biomass. To assess the abiotic drivers regulating Raphidiopsis or Microcystis dominance during persistent blooms, we used a “Raphidiopsis index” (i.e., R-index), which is the ratio between the biomass of Raphidiopsis and the sum of the biomass of Raphidiopsis plus Microcystis. Here, 0.5 means equal biomass of both taxa, 1.0 represents absolute dominance of Raphidiopsis, and 0 (zero) indicates absolute dominance of Microcystis. The R-index was calculated for the three eutrophic lakes where the bloom consisted mostly of Raphidiopsis or Microcystis (i.e., 3 out of the 4 bloom dominated lakes). The R-index result was compared to all abiotic variables measured (Zeu, Zmax, TP, TDP, TN, TDN, TSS, VSS, and FSS) to identify the difference in environmental conditions where Microcystis or Raphidiopsis populations dominate. The Chl-a/TP ratio indicates phytoplankton resource efficiency, values equal to 1:1 indicating maximal resource use efficiency which phytoplankton can make use of the carrying capacity, while the ratio can increase at low values of TP or higher values of Chl-a under light limitation conditions (Reynolds, 1992; Chorus & Spijkerman, 2020).

Statistical analyses

The relationships between Zmax, total and dissolved nutrients, phytoplankton, and cyanobacterial biomass were evaluated with single factor generalized linear models (GLM). The deviance value (%D) provided by the GLM analysis shows the percent of the variability in the dependent variable that is explained by the independent variable(s). The normality of the data was confirmed via Shapiro–Wilk test and when necessary, variables were log10 (x) or log10 (x + 1) transformed to meet the assumptions of linear models: The specific transformations can be seen in the regression equations for each GLM (Table 3). The criterion of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team, 2018).

Results

Based on eutrophication threshold values regarding TP and Chl-a, the lakes ranged from mesotrophic (Sta. Cruz and Prata) to eutrophic (Encanto, Boq. Parelhas and Pajuçara) (Table 2). Tabatinga lake was considered meso-eutrophic, with TP concentrations below the eutrophic threshold and Chl-a concentrations above the eutrophic threshold (Table 2). Euphotic depth (Zeu) was highest for the mesotrophic and lowest for enriched lakes (Table 2). TDP was always above 3 µg l−1, expecting one month in Sta. Cruz, and TDN above 450 µg l−1 (Table 2). TP ranged from 12.83 to 231.89 µg l−1, TN from 500.30 to 6864.00 µg l−1, and Chl-a from 0.45 to 193.65 µg l−1 among lakes (Table 2). The Chl-a/TP ratio varied from 0.02 to 1.44 during our study and was seldom above the maximal resource use efficiency (1:1), only 6 out of 71 samples, the lowest overall annual mean value in Sta. Cruz (0.07) and highest annual mean in Tabatinga (0.75). Total suspended solids (TSS), volatile suspended solids (VSS) and fixed suspended solids (FSS) were higher in the eutrophic and meso-eutrophic lakes (Table 2). Most of the lakes had a mean temperature of 28°C (Table 2). The lakes were well mixed and the difference between the temperatures of the surface versus deepest layer was less than 1°C save a single exception.

As expected, the mesotrophic lakes (Sta. Cruz and Prata) had the lowest mean biomass of total phytoplankton (0.60 and 3.90 mg. mg l−1; Table 2) and cyanobacteria (0.05 and 0.70 mg l−1; Table 2). In contrast, the most nutrient-enriched lakes (Boq. Parelhas and Pajuçara) had the highest mean phytoplankton (149.24 and 97.29 mg l−1; Table 2) and cyanobacteria biomass (148.19 and 94.40 mg l−1; Table 2). The mesotrophic lakes were characterized by a more diversified phytoplankton composition. Sta. Cruz was mostly dominated by Bacillariophyceae with cyanobacteria dominance only in January, while Prata was mostly dominated by Chlorophyceae with cyanobacteria dominance from October to December (Fig. 2a, b). Tabatinga had a more pronounced dominance of cyanobacteria (Fig. 2c), and the eutrophic lakes (Encanto, Boq. Parelhas e Pajuçara) had persistent dominance of cyanobacteria virtually during the entire year (Fig. 2d–f). Thus, increased dominance of cyanobacteria corresponded closely to the decline in the relative abundance of eukaryotic phytoplankton in the more eutrophic lakes.

Cyanobacteria dominated the phytoplankton community (i.e., cyanobacteria > 50% of phytoplankton biomass) in the meso-eutrophic (Tabatinga) and the three eutrophic lakes (Boq. Parelhas, Pajuçara, and Encanto) for most months of the year (Fig. 2). Moreover, the three eutrophic lakes had high cyanobacterial dominance throughout the year save one month, and cyanobacteria was > 80% of the total phytoplankton biomass for at least nine months over the year (Fig. 2). In the eutrophic lake Boq. Parelhas, cyanobacteria was always > 80% of total phytoplankton biomass (Fig. 2).

During these persistent blooms of cyanobacteria (i.e., lakes with 11 months of cyanobacterial dominance per year), the dominant cyanobacterial taxa differed among lakes over time. In the eutrophic lakes, the high cyanobacteria dominance was manifested in high biomass throughout the year and total cyanobacteria biomass was nearly equal to phytoplankton biomass. The dominant genera in these eutrophic lakes (Boq. Parelhas, Pajuçara, and Encanto) was either Raphidiopsis raciborskii (Woloszynska) Aguilera, Berrendero Gómez, Kastovsky, Echenique & Salerno, or Microcystis aeruginosa (Kützing) Kützing, and these two species rarely co-occurred (Fig. 3d–f). Encanto and Pajuçara had a temporal switch of dominance between these species (Fig. 3d, f). Pseudanabaena catenata Lauterborn also appeared from January to March in Encanto (Fig. 3d). Microcystis aeruginosa represented the highest biomass achieved in the meso-eutrophic and all eutrophic lakes (Fig. 3c–f). In the meso-eutrophic lake, Tabatinga, cyanobacteria biomass varied with time, and in most months cyanobacteria biomass dominated the phytoplankton community (Fig. 2); the dominant species was Planktolyngbya limnetica (Lemmermann) Komárková-Legnerová & Cronberg, though Microcystis panniformis Komárek reached the highest biomass in April (55.30 mg l−1) (Fig. 3c). In contrast, cyanobacteria biomass contributed very little to phytoplankton total biomass in the mesotrophic lakes most of the months (i.e., 7 months cyanobacteria < 10% of phytoplankton biomass in both lakes), where the main species found was Aphanocapsa sp. in Sta. Cruz and Prata, though Planktolyngbya sp. also appeared in Prata (Fig. 3a, b).

Generalized linear regressions with single factor predictors indicated that Zmax was significantly and negatively correlated to TP (Fig. 4a; Table 3), and also TDP, TN, and TDN (P < 0.001 see Table 1 in Online Resource), and total phytoplankton biomass (Fig. 4b; Table 3). In general, lower lake depth corresponded to an order of magnitude increase in phytoplankton biomass (Fig. 4b). In turn, TP was significantly and positively correlated to cyanobacteria biomass (Fig. 4c; Table 3), Chl-a (Fig. 4d; Table 3), and total phytoplankton (Fig. 4e, Table 3). Based on the deviance value, TP explained 37% of the variability in cyanobacteria biomass, 61% of Chl-a, and 38% of phytoplankton biomass (Table 3). Besides, total phytoplankton was significantly and negatively correlated to Zeu (Fig. 4f; Table 3), while Chl-a was significantly positively correlated to TSS (Fig. 4g; Table 3) and negatively to Zeu (Fig. 4h; Table 3).

GLM regressions showing the relationship between maximum depth (Zmax) and a total phosphorous (µg l−1) and b phytoplankton biomass (mg l−1). Also between total phosphorus (µg l−1) and c cyanobacteria biomass (mg l−1); d Chl-a (µg l−1); and e total phytoplankton biomass (mg l−1). Also between euphotic zone depth (Zeu) and f phytoplankton biomass (mg l−1); g Chl-a (µg l−1); and between h total suspended solids (TSS) (mg l−1) and Chl-a (µg l−1). Dots represent all samples from the six study lakes from January to December of 2017. The line shows the fit while the shaded area shows the 95% confidence interval for each regression

Given that Raphidiopsis and Microcystis were the most representative genera of cyanobacteria in the lakes with persistent dominance of cyanobacteria (Fig. 3), the “R-index” was applied to explore the range of environmental conditions that corresponded to the dominance of these genera in the three eutrophic lakes (see methods for details). Microcystis dominated when TP was < 123 µg l−1 (Fig. 5a); when TDN was < 2260 µg l−1 (Fig. 5b); and when TSS was < 16.5 mg l−1 (Fig. 5c). In contrast, Raphidiopsis dominated in environments with a higher range of nutrient concentrations from 39 to 231 µg l−1 TP (Fig. 5a); 953–4910 µg l−1 TDN (Fig. 5b); and 3–47 mg l−1 TSS (Fig. 5c). Moreover, Microcystis dominated in environments with a relatively deeper euphotic depth and was never dominant when the euphotic depth was < 1.1 m (Fig. 5d). Conversely, Raphidiopsis dominated at a wider range of euphotic depth, including those < 1.1 m (Fig. 5d). Temporal co-occurrence between Raphidiopsis and Microcystis was seldom observed. Specifically, out of a total 36 samples, only one (~ 3%) had a R-index between 0.4 and 0.6 (i.e., temporal co-occurrence of the cyanobacterial taxa). Moreover, only 4 out of 36 samples had an R-index between 0.1 and 0.9, indicating that in 86% of the samples either Microcystis or Raphidiopsis dominated the cyanobacterial bloom biomass (i.e., > 90% of total).

Raphidiopsis Index in relation to a dissolved nitrogen (µg l−1), b total phosphorous (µg l−1), c total suspended solids (mg l−1), and d euphotic zone (m). Horizontal black dash lines represent equal biomass for both genera, 0 means 100% dominance of Microcystis, and 1 means 100% dominance of Raphidiopsis

Discussion

As expected, the biomass of phytoplankton and bloom-forming cyanobacteria increased along the lake´s trophic state gradient. The frequency of cyanobacterial dominance also increased from episodic to perennial year-round blooms from mesotrophic lakes to eutrophic lakes, corresponding to a parallel decline in the relative contribution of eukaryotic phytoplankton. Moreover, the negative relationship between lake depth and nutrient concentration or phytoplankton biomass emphasizes the role of drought associated water level reduction in intensifying the effects of eutrophication (Naselli-Flores, 2003; Aldridge, 2014; Bakker & Hilt, 2016; Brasil et al., 2016; Costa et al., 2016; Havens et al., 2019). Despite the variety of physical, chemical, and biological factors shown to control cyanobacterial blooms, the concentration of nutrients (P and N) is often the key driver of cyanobacteria biomass even in tropical regions with year-round availability of light and high temperatures (Paerl, 2017; Amorim et al., 2020). Indeed, all eutrophic lakes in this study displayed perennial year-round blooms and highlights the potential for constant optimal conditions for cyanobacterial dominance in shallow tropical reservoirs (Figueiredo & Giani, 2009; Soares et al., 2009; Figueredo et al., 2016; Lind et al., 2016; Batista et al., 2018).

Arid and semiarid regions face drastic changes in water levels as a consequence of recurrent drought and short rainy periods that modify physical and chemical water characteristics affecting phytoplankton biomass and community structure (Naselli-Flores, 2003; Medeiros et al., 2015). Several studies demonstrated that water depth changes induced by drought can cause an increase in nutrient concentration, favor cyanobacteria dominance, and result in profound impacts on water quality (Naselli-Flores, 2003; Aldridge, 2014; Mosley, 2015; Brasil et al., 2016; Rocha Junior et al., 2018; Havens et al., 2019; Amorim et al., 2020). We found similar results as shallower lakes had higher concentrations of total and dissolved nutrient concentrations and the phytoplankton community was composed mainly of cyanobacteria. In many cases, droughts lead to reduced water level, increased residence time, and reduced dilution capacity in freshwater systems (Mosley, 2015). Besides the increase in nutrient concentration, drought reduces hydrologic flushing events, so that once a bloom is established it persists until the next flushing (Medeiros et al., 2015; Paerl, 2018). Besides, the reduction of depth may enhance sediment resuspension to the water column, allowing for internal P loading. This may be have been an important source of phosphorus to the studied lakes, since shallow semiarid lakes are susceptible to the internal release of P under certain environmental conditions such as low depths and resuspension of sediment due to the wind drive mixing (Cavalcante et al., 2018). Overall, our findings corroborate previous results highlighting the vulnerability of shallow eutrophic tropical lakes to the role of nutrients for drought-triggered cyanobacteria blooms (Bouvy et al., 2000; Bittencourt-Oliveira et al., 2012; Braga et al., 2015; Medeiros et al., 2015; Costa et al., 2016; Walter et al., 2018).

Our results also highlight factors regulating the composition of perennial year-round tropical cyanobacterial blooms. A key result was that the two main bloom-forming genera (i.e., Raphidiopsis and Microcystis) almost never co-occurred in time, as shown by the R-index. We show that TP correlated positively with phytoplankton and cyanobacteria biomass; meanwhile, light availability (as indicated by euphotic depth in this study) may be an important regulator of cyanobacterial species composition in tropical eutrophic lakes. Specifically, the filamentous cyanobacterium Raphidiopsis dominated in more turbid (i.e., euphotic depths < 1.1 m) and nutrient-enriched waters. Also, Raphidiopsis generally occurred in a wider range of abiotic conditions compared to the colonial Microcystis. Similarly, while Microcystis did not occur at TP higher than 170 µg l−1, Raphidiopsis was present up to the maximum TP concentration observed in our study (~ 230 µg l−1). In contrast, both cyanobacterial species occurred similarly across a gradient of TDP, which suggests that turbidity—not TP—was the main driver of cyanobacterial species composition. Hence, our results build on previous reports linking higher water transparency with Microcystis dominance during perennial blooms (Soares et al., 2009; Batista et al., 2018).

Raphidiopsis is a shade-tolerant species that can form persistent blooms despite self-shading (Padisák, 1997). In contrast, Microcystis forms surface blooms and tolerates high levels of UV radiation due to the enhancement of photoprotective pigments and carotenoid (Paerl et al., 1985). Hence, Microcystis thrives in environments with high insolation and it is sensitive to low total light availability (Reynolds et al., 2002; Batista et al., 2018). Our results support the conclusion of these studies, and further indicate that Microcystis can be expected to be replaced by Raphidiopsis after reductions in euphotic depth due to increased phytoplankton biomass, Chl-a, and turbidity (TSS) during perennial cyanobacterial blooms. In general, the flexibility of Raphidiopsis adaptations to a wide range of environmental conditions (e.g., light, nutrients, TSS) via strain-specific responses has been linked to its expanding global success as bloom-forming cyanobacteria (Briand et al., 2004; Bonilla et al., 2012; Burford et al., 2016). Thus, while our results suggest that reduced water transparency may be expected to shift the dominance from Microcystis to Raphidiopsis during perennial tropical cyanobacterial blooms, the eco-physiology of cyanobacterial species including Raphidiopsis and Microcystis can have significant strain-specific variability in their responses to light and nutrients (Guedes et al., 2019).

The biomass of Planktolyngbya, a shade-adapted filamentous cyanobacterium (Fabbro & Duivenvoorden, 2000), was related to higher concentrations of suspended solids (VSS and TSS) and shallower depth, dominating year-round in the meso-eutrophic Tabatinga lake. In agreement with previous reports, Planktolyngbya has been associated with turbid environments, with mixed layers and relatively lower values of phosphate in Brazilian semiarid lakes (Pinto and Becker 2015; Barroso et al. 2018). Meanwhile, Aphanocapsa, a coccoid cyanobacterium typically found in eutrophic environments (Padisák et al., 2009), was detected under mesotrophic conditions and associated to lower suspended solids and deeper water depth (Zmax). Although the dominance of Aphanocapsa was rare in the studied lakes, microcystin-producing variants of this genus have been frequently found in other semiarid man-made lakes (Domingos et al., 1999; Marcon et al., 2017), making it a potential threat to water quality.

The connection between warmer temperatures and cyanobacteria dominance is well established (Paerl & Huisman, 2008; Paerl & Otten, 2013; Visser et al., 2016; Paerl, 2017; Paerl et al., 2020), even in the tropics (Bouvy et al., 2000; Huszar et al., 2000; Soares et al., 2009). In our study, water temperature did not relate to the biomass or composition of cyanobacteria. During the sampling period, water temperatures often exceeded 25°C, which is the expected threshold for optimal growth (Paerl, 2018). In a previous microcosm experiment with samples from one of the eutrophic lakes in this study (Boq. Parelhas), bloom-forming cyanobacterial abundance was not favored in the warmer and nutrient-enriched treatment (de Souza et al., 2018). This may indicate that temperature is not a main driver of phytoplankton assemblage in tropical semiarid lakes, likely because temperatures are already optimal and, thus, non-limiting.

Results also indicate that nutrients were not limiting phytoplankton biomass based on nutrient concentrations as well as the Chl-a/TP ratio. Specifically, nutrients were always above concentrations considered limiting for phytoplankton uptake (3–10 µg l−1 SRP or 100–130 µg l−1 DIN) (Reynolds, 2006; Chorus & Spijkerman, 2020) with TDN more than tenfold higher than TDP. Yet, considering that nitrogen was always above the saturation threshold for phytoplankton nutrient uptake rate, TP was likely determining the carrying capacity of the system. Indeed, TP represents the total pool of phosphorous in the water, and the greater is the pool, the greater is the phytoplankton biomass sustained. High TP values here, however, do not exclude the possibility that other factors such as light or grazers might be limiting the carrying capacity (Reynolds, 1992, 2006; Chorus & Spijkerman, 2020). Indeed, that Chl-a/TP values were mostly < 1 in this study indicates that factors other than TP were likely limiting phytoplankton biomass (Reynolds, 1992; Chorus & Spijkerman, 2020). That said, some of the lakes here, including eutrophic ones, occasionally had Chl-a/TP values close to 1, suggesting that maximal resource use efficiency (i.e., all available TP converted to Chl-a biomass) was at least sometimes attained.

Future climate scenarios emphasize, besides warming, that land affected by drought will expand in North and South America, Africa, southern Europe, and Australia (Feng & Fu, 2013; Huang et al., 2016). The combination of warming, dryland expansion, and increased sediment loading due to land use change (Donohue & Garcia Molinos, 2009; Moss, 2011) may increase cyanobacterial bloom duration and favor Raphidiopsis, at least in shallow lakes. Raphidiopsis has been long recognized as an invader species (Padisák, 1997; Antunes et al., 2015) and a further increase in the expansion of the species populations dominance is worrisome due to the suite of toxins they can produce (neurotoxins and cytotoxins).

Finally, our results raise a public health concern regarding the use of the studied lakes for fish cage production as intended. The introduction of fish food in the systems increases nutrient input, which will likely increase the risk of eutrophication in the lower trophic state lakes (Gorlach-Lira et al., 2013; Henry-Silva et al., 2019). While we did not measure cyanobacterial toxicity here, microcystins from Microcystis and saxitoxins from Raphidiopsis are widely reported from other lakes within the same semiarid region of the state of Rio Grande do Norte where the study lakes are, and also from Brazilian Semiarid lakes in general (Molica et al., 2005; Bittencourt-Oliveira et al., 2014; Fonseca et al., 2015; Lorenzi et al., 2018; Moura et al., 2018). Hence, it is likely that cyanotoxins were prevalent in our study lakes as well. Given that fish may accumulate cyanotoxins (Lee et al., 2017), the consumption of fish from these lakes raises additional public health concerns. Furthermore, the economic sustainability of fish cage production in such lakes may be questionable since sub-lethal effects of cyanotoxins even at low concentrations (Calado et al., 2019) may decrease fish health and growth (Drobac et al., 2016).

Conclusion

Overall, our results indicate that in shallow tropical semiarid man-made lakes (i) low water level caused by prolonged drought, and higher concentrations of TP, is a key factor leading to perennial cyanobacteria dominance and (ii) reduced light availability (via reduced water transparency) is a key factor regulating the dominance of Microcystis or Raphidiopsis in year-round perennial blooms in shallow tropical lakes. Raphidiopsis thrives under higher nutrients and suspended solids (lower light) in lakes where the temperature is not a constraint. Equally important, since reports on the dynamics of truly perennial cyanobacterial blooms are scarce, the present study provides useful information for developing strategies for bloom control and management in tropical shallow lakes under dry climates. We encourage future studies to use abundance indices similar to the “R-index” here when evaluating factors associated with shifts in cyanobacterial dominance during longer duration blooms.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aldridge, K., 2014. Impact of a drought on nutrient concentrations in the Lower Lakes (Murray Darling Basin, Australia). Inland Waters 1: 159–176.

Alvares, C. A., J. L. Stape, P. C. Sentelhas, J. L. De Moraes Gonçalves, & G. Sparovek, 2013. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorologische Zeitschrift 22: 711–728.

Amorim, C. A., Ê. W. Dantas, & A. do N. Moura, 2020. Modeling cyanobacterial blooms in tropical reservoirs: the role of physicochemical variables and trophic interactions. Science of the Total Environment 744: 140659.

Antunes, J. T., P. N. Leão, & V. M. Vasconcelos, 2015. Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii: review of the distribution, phylogeography, and ecophysiology of a global invasive species. Frontiers in Microbiology 6: 473.

Aylward, B., J. Bandyopadhyay, J.-C. Belausteguigotia, P. Börkey, A. Cassar, L. Meadors, L. Saade, M. Siebentritt, R. Stein, S. Tognetti, C. Tortajada, T. Allan, C. Bauer, C. Bruch, A. Guimaraes-Pereira, M. Kendall, B. Kiersch, C. Landry, E. M. Rodriguez, R. Meinzen-Dick, SuzanneMoellendorf, S. Pagiola, I. Porras, B. Ratner, A. Shea, B. Swallow, T. Thomich, N. Voutchkov, C. Lead, A. Bruce, L. Authors, P. Bo, C. Authors, S. Moellendorf, R. Editors, R. Constanza, P. Jacobi, & F. Rijsberman, 2005. Freshwater Ecosystem Services. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Current State and Trends. Washington DC: Island Press.

Bakker, E. S., & S. Hilt, 2016. Impact of water-level fluctuations on cyanobacterial blooms: options for management. Aquatic Ecology Springer Netherlands 50: 485–498.

Barroso, H. S., J. A. dos Santos, R. V. Marins, & L. D. de Lacerda, 2018. Assessing temporal and spatial variability of phytoplankton composition in a large reservoir in the Brazilian northeastern region under intense drought conditions. Journal of Limnology 77: 130–146.

Batista, A. M. M., C. C. Figueredo, & A. Giani, 2018. Variability in a permanent cyanobacterial bloom: species-specific responses to environmental drivers. FEMS Microbiology Ecology NLM (Medline) 94: 197.

Bittencourt-Oliveira, M. C., S. N. Dias, A. N. Moura, M. K. Cordeiro-Araújo, & E. W. Dantas, 2012. Seasonal dynamics of cyanobacteria in a eutrophic reservoir (Arcoverde) in a semi-arid region of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Biology 72: 533–544.

Bittencourt-Oliveira, M. D. C., V. Piccin-Santos, A. N. Moura, N. K. C. Aragão-Tavares, & M. K. Cordeiro-Araújo, 2014. Cyanobacteria, microcystins and cylindrospermopsin in public drinking supply reservoirs of Brazil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 86: 297–309.

Bonilla, S., L. Aubriot, M. C. S. Soares, M. González-Piana, A. Fabre, V. L. M. Huszar, M. Lürling, D. Antoniades, J. Padisák, & C. Kruk, 2012. What drives the distribution of the bloom-forming cyanobacteria Planktothrix agardhii and Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii?. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 79,: 594–607.

Bonilla, S., M. González-Piana, M. C. S. Soares, V. L. M. Huszar, V. Becker, A. Somma, M. M. Marinho, M. Kokociński, M. Dokulil, D. Antoniades, & L. Aubriot, 2016. The success of the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in freshwaters is enhanced by the combined effects of light intensity and temperature. Journal of Limnology 75: 606–617.

Bouvy, M., D. Falcão, M. Marinho, M. Pagano, & A. Moura, 2000. Occurrence of Cylindrospermopsis (Cyanobacteria) in 39 Brazilian tropical reservoirs during the 1998 drought. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 23: 13–27.

Bouvy, M., S. M. Nascimento, R. J. R. Molica, A. Ferreira, V. Huszar, & S. M. F. O. Azevedo, 2003. Limnological features in Tapacurá reservoir (northeast Brazil) during a severe drought. Hydrobiologia 493: 115–130.

Braga, G. G., & V. Becker, 2020. Influence of water volume reduction on the phytoplankton dynamics in a semiarid man-made lake: a comparison of two morphofunctional approaches. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias 92: 1–17.

Braga, G. G., V. Becker, J. N. P. de Oliveira, J. R. de Mendonça Junior, A. F. de M. Bezerra, L. M. Torres, Â. M. F. Galvão, & A. Mattos, 2015. Influence of extended drought on water quality in tropical reservoirs in a semiarid region. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 27: 15–23.

Brasil, J., J. L. Attayde, F. R. Vasconcelos, D. D. F. Dantas, & V. L. M. Huszar, 2016. Drought-induced water-level reduction favors cyanobacteria blooms in tropical shallow lakes. Hydrobiologia 770: 145–164.

Briand, J. F., C. Leboulanger, J. F. Humbert, C. Bernard, & P. Dufour, 2004. Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Cyanobacteria) invasion at mid-latitudes: selection, wide physiological tolerance, or global warming?. Journal of Phycology 40: 231–238.

Burford, M. A., J. Beardall, A. Willis, P. T. Orr, V. F. Magalhaes, L. M. Rangel, S. M. F. O. E. Azevedo, & B. A. Neilan, 2016. Understanding the winning strategies used by the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Harmful Algae . 54: 44–53.

Calado, S. L. de M., M. Vicentini, G. S. Santos, A. Pelanda, H. Santos, L. A. Coral, V. de F. Magalhães, M. Mela, M. M. Cestari, & H. C. Silva de Assis, 2019. Sublethal effects of microcystin-LR in the exposure and depuration time in a neotropical fish: multibiomarker approach. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 183: 109527.

Carmichael, W. W., 1992. Cyanobacteria secondary metabolites—the cyanotoxins. Journal of Applied Bacteriology. 72, 445–459.

Cavalcante, H., F. Araújo, & V. Becker, 2018. Phosphorus dynamics in the water of tropical semiarid reservoirs in a prolonged drought period. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 30:e105.

Chanlett, E. T., 1947. Standard methods for the examination of water and sewage. American Journal of Public Health and the Nations Health American Public Health Association 37: 1053–1054.

Chorus, I., & E. Spijkerman, 2020. What Colin Reynolds could tell us about nutrient limitation, N:P ratios and eutrophication control. Hydrobiologia; 848:95-108.

Cirés, S., M. C. Casero, & A. Quesada, 2017. Toxicity at the edge of life: a review on cyanobacterial toxins from extreme environments. Marine Drugs. 15, 233.

Cole, G., 1994. Textbook of Limnology. Waveland Press., Illinois.

Costa, M. R. A., J. L. Attayde, & V. Becker, 2016. Effects of water level reduction on the dynamics of phytoplankton functional groups in tropical semi-arid shallow lakes. Hydrobiologia 778: 75–89.

Costa, M. R. A., R. F. Menezes, H. Sarmento, J. L. Attayde, L. da S. L. Sternberg, & V. Becker, 2019. Extreme drought favors potential mixotrophic organisms in tropical semi-arid reservoirs. Hydrobiologia 831: 43–54.

Crossetti, L. O., D. de C. Bicudo, L. M. Bini, R. B. Dala-Corte, C. Ferragut, & C. E. de Mattos Bicudo, 2019. Phytoplankton species interactions and invasion by Ceratium furcoides are influenced by extreme drought and water-hyacinth removal in a shallow tropical reservoir. Hydrobiologia 831: 71–85.

de Souza, M. da C., L. O. Crossetti, & V. Becker, 2018. Effects of temperature increase and nutrient enrichment on phytoplankton functional groups in a brazilian semi-arid reservoir. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 30:e215.

Dokulil, M. T., & K. Teubner, 2000. Cyanobacterial dominance in lakes. Hydrobiologia 438: 1–12.

Domingos, P., T. K. Rubim, R. J. R. Molica, S. M. F. O. Azevedo, & W. W. Carmichael, 1999. First report of microcystin production by picoplanktonic cyanobacteria isolated from a northeast Brazilian drinking water supply. Environmental Toxicology 14: 31–35.

Donohue, I., & J. Garcia Molinos, 2009. Impacts of increased sediment loads on the ecology of lakes. Biological Reviews 84: 517–531.

Drobac, D., N. Tokodi, J. Lujić, Z. Marinović, G. Subakov-Simić, T. Dulić, T. Važić, S. Nybom, J. Meriluoto, G. A. Codd, & Z. Svirčev, 2016. Cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins in fishponds and their effects on fish tissue. Harmful Algae 55: 66–76.

EPA, 2015. A Compilation of Cost Data Associated with the Impacts and Control of Nutrient Pollution. EPA 820-F-15–096. .

Fabbro, L. D., & L. J. Duivenvoorden, 2000. A two-part model linking multidimensional environmental gradients and seasonal succession of phytoplankton assemblages. Hydrobiologia 438: 13–24.

Feng, S., & Q. Fu, 2013. Expansion of global drylands under a warming climate. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 13: 10081–10094.

Figueiredo, A. do V., & V. Becker, 2018. Influence of extreme hydrological events in the quality of water reservoirs in the semi-arid tropical region. Rbrh 23: 1–8.

Figueredo, C. C., & A. Giani, 2009. Phytoplankton community in the tropical lake of Lagoa Santa (Brazil): conditions favoring a persistent bloom of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii. Limnologica 39: 264–272.

Figueredo, C. C., R. M. Pinto-Coelho, A. M. M. B. Lopes, P. H. O. Lima, B. Gücker, & A. Giani, 2016. From intermittent to persistent cyanobacterial blooms: Identifying the main drivers in an urban tropical reservoir. Journal of Limnology 75: 445–454.

Fonseca, B. M., C. Ferragut, A. Tucci, L. O. Crossetti, F. Ferrari, D. de C. Bicudo, C. L. Sant’Anna, & C. E. de M. Bicudo, 2014. Biovolume de cianobactérias e algas de reservatórios tropicais do Brasil com diferentes estados tróficos. Hoehnea 41: 9–30.

Fonseca, J. R., P. C. S. Vieira, P. Kujbida, & I. A. S. da Costa, 2015. Cyanobacterial occurrence and detection of microcystins and saxitoxins in reservoirs of the Brazilian semi-arid. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 27: 78–92.

Gallard, H., & U. Von Gunten, 2002. Chlorination of natural organic matter: kinetics of chlorination and of THM formation. Water Research Elsevier Ltd 36: 65–74.

Giani, A., Z. E. Taranu, G. von Rückert, & I. Gregory-Eaves, 2020. Comparing key drivers of cyanobacteria biomass in temperate and tropical systems. Harmful Algae 97: 101859.

González-Madina, L., J. P. Pacheco, L. Yema, P. de Tezanos, P. Levrini, J. Clemente, C. Crisci, J. J. Lagomarsino, G. Méndez, C. Fosalba, G. Goyenola, & N. Mazzeo, 2019. Drivers of cyanobacteria dominance, composition and nitrogen fixing behavior in a shallow lake with alternative regimes in time and space, Laguna del Sauce (Maldonado, Uruguay). Hydrobiologia 829: 61–76.

Gorlach-Lira, K., C. Pacheco, L. C. T. Carvalho, H. N. Melo Júnior, & M. C. Crispim, 2013. The influence of fish culture in floating net cages on microbial indicators of water quality. Brazilian Journal of Biology 73: 457–463.

Guedes, I. A., A. B. F. Pacheco, M. C. P. Vilar, M. M. Mello, M. M. Marinho, M. Lurling, & S. M. F. O. Azevedo, 2019. Intraspecific variability in response to phosphorus depleted conditions in the cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa and Raphidiopsis raciborskii. Harmful Algae 86: 96–105.

Harke, M. J., T. W. Davis, S. B. Watson, & C. J. Gobler, 2016. Nutrient-controlled niche differentiation of western lake erie cyanobacterial populations revealed via metatranscriptomic surveys. Environmental Science and Technology 50: 604–615.

Havens, K. E., G. Ji, J. R. Beaver, R. S. Fulton, & C. E. Teacher, 2019. Dynamics of cyanobacteria blooms are linked to the hydrology of shallow Florida lakes and provide insight into possible impacts of climate change. Hydrobiologia 829: 43–59.

Henry-Silva, G. G., H. D. N. Melo-Junior, & J. L. Attayde, 2019. Extreme drought events and the sustainability of fish farming in net cages in reservoirs of the semi-arid northeastern region in Brazil. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 31: 10-15.

Hillebrand, H., 1999. Biovolume calculation for palagic and benthic microalgae. Journal of Phycology 424: 403–424.

Huang, J., H. Yu, X. Guan, G. Wang, & R. Guo, 2016. Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change. Nature Climate Change 6: 166–171.

Huisman, J., J. Sharples, J. M. Stroom, P. M. Visser, W. E. A. Kardinaal, J. M. H. Verspagen, & B. Sommeijer, 2004. Changes in turbulent mixing shift competition for light between phytoplankton species. Ecology 85: 2960–2970.

Huszar, V. L. M., L. H. S. Silva, M. Marinho, P. Domingos, & C. L. Sant’Anna, 2000. Cyanoprokaryote assemblages in eight productive tropical Brazilian waters. Hydrobiologia 424: 67–77.

Jespersen, A. M., & K. Christoffersen, 1987. Measurements of chlorophyll-a from phytoplankton using ethanol as extraction solvent. Archiv für Hydrobiologie 109: 445-454.

Kosten, S., V. L. M. Huszar, E. Bécares, L. S. Costa, E. van Donk, L. A. Hansson, E. Jeppesen, C. Kruk, G. Lacerot, N. Mazzeo, L. De Meester, B. Moss, M. Lürling, T. Nõges, S. Romo, & M. Scheffer, 2012. Warmer climates boost cyanobacterial dominance in shallow lakes. Global Change Biology 18: 118–126.

Le Moal, M., C. Gascuel-Odoux, A. Ménesguen, Y. Souchon, C. Étrillard, A. Levain, F. Moatar, A. Pannard, P. Souchu, A. Lefebvre, & G. Pinay, 2019. Eutrophication: a new wine in an old bottle?. Science of the Total Environment. 651, 1–11.

Lee, J., S. Lee, & X. Jiang, 2017. Cyanobacterial toxins in freshwater and food: important sources of exposure to humans. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology Annual Reviews 8: 281–304.

Leitão, E., K. A. Ger, & R. Panosso, 2018. Selective grazing by a tropical copepod (Notodiaptomus iheringi) facilitates Microcystis dominance. Frontiers in Microbiology 9: 301.

Lind, O., L. Dávalos-Lind, C. López, M. López, & J. Dyble Bressie, 2016. Seasonal morphological variability in an in situ Cyanobacteria monoculture: example from a persistent Cylindrospermopsis bloom in Lake Catemaco, Veracruz, Mexico. Journal of Limnology 75: 66–80.

Lorenzi, A. S., M. K. Cordeiro-Araújo, M. A. Chia, & M. do C. Bittencourt-Oliveira, 2018. Cyanotoxin contamination of semiarid drinking water supply reservoirs. Environmental Earth Sciences 77:. 179-188

Lund, J. W. G., C. Kipling, & E. D. Le Cren, 1958. The inverted microscope method of estimating algal numbers and the statistical basis of estimations by counting. Hydrobiologia 11: 143–170.

Ma, J., B. Qin, H. W. Paerl, J. D. Brookes, N. S. Hall, K. Shi, Y. Zhou, J. Guo, Z. Li, H. Xu, T. Wu, & S. Long, 2016. The persistence of cyanobacterial (Microcystis spp.) blooms throughout winter in Lake Taihu, China. Limnology and Oceanography 61: 711–722.

Mantzouki, E., P. M. Visser, M. Bormans, & B. W. Ibelings, 2016. Understanding the key ecological traits of cyanobacteria as a basis for their management and control in changing lakes. Aquatic Ecology 50: 333–350.

Marcon, A. E., J. A. Navoni, M. F. de Oliveira Galvão, A. C. F. S. Garcia, V. S. do Amaral, R. A. Petta, T. F. da C. Campos, R. Panosso, A. L. Quinelato, & S. R. B. de Medeiros, 2017. Mutagenic potential assessment associated with human exposure to natural radioactivity. Chemosphere 167: 36–43.

Marengo, J. A., L. M. Alves, R. C. S. Alvala, A. P. Cunha, S. Brito, & O. L. L. Moraes, 2018. Climatic characteristics of the 2010-2016 drought in the semiarid northeast Brazil region. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias Academia Brasileira de Ciências 90: 1973–1985.

Marengo, J. A., A. P. M. A. Cunha, C. A. Nobre, G. G. Ribeiro Neto, A. R. Magalhaes, R. R. Torres, G. Sampaio, F. Alexandre, L. M. Alves, L. A. Cuartas, K. R. L. Deusdará, & R. C. S. Álvala, 2020. Assessing drought in the drylands of northeast Brazil under regional warming exceeding 4 °C. Natural Hazards 103: 1–23.

Marengo, J. A., R. R. Torres, & L. M. Alves, 2017. Drought in Northeast Brazil—past, present, and future. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 129: 1189–1200.

McGregor, G. B., & L. D. Fabbro, 2000. Dominance of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Nostocales, Cyanoprokaryota) in Queensland tropical and subtropical reservoirs: implications for monitoring and management. Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management 5: 195–205.

Medeiros, L., A. Mattos, M. Lürling, & V. Becker, 2015. Is the future blue-green or brown? The effects of extreme events on phytoplankton dynamics in a semi-arid man-made lake. Aquatic Ecology 49: 293–307.

Menezes, R. S. C., E. V. S. B. Sampaio, V. Giongo, & A. M. Pérez-Marin, 2012. Ciclagem biogeoquímica em ecossistemas terrestres do bioma Caatinga. Brazilian Journal of Biology 72: 643–653.

Merel, S., D. Walker, R. Chicana, S. Snyder, E. Baurès, & O. Thomas, 2013. State of knowledge and concerns on cyanobacterial blooms and cyanotoxins. Environment International 59: 303–327.

Molica, R. J. R., E. J. A. Oliveira, P. V. V. C. Carvalho, A. N. S. F. Costa, M. C. C. Cunha, G. L. Melo, & S. M. F. O. Azevedo, 2005. Occurrence of saxitoxins and an anatoxin-a(s)-like anticholinesterase in a Brazilian drinking water supply. Harmful Algae 4: 743–753.

Mosley, L. M., 2015. Drought impacts on the water quality of freshwater systems; review and integration. Earth-Science Reviews 140: 203–214.

Moss, B., 2011. Allied attack: climate change and eutrophication. Inland Waters 1: 101–105.

Moura, A. D. N., N. K. C. AragãO-Tavares, & C. A. Amorim, 2018. Cyanobacterial blooms in freshwater bodies from a semiarid region, northeast brazil: a review. Journal of Limnology 77: 179–188.

Mowe, M. A. D., S. M. Mitrovic, R. P. Lim, A. Furey, & D. C. J. Yeo, 2015. Tropical cyanobacterial blooms: a review of prevalence, problem taxa, toxins and influencing environmental factors. Journal of Limnology, 74: 205–224.

Muir, D. G., & R. Perissinotto, 2011. Persistent phytoplankton bloom in Lake St. Lucia (iSimangaliso Wetland Park, South Africa) caused by a cyanobacterium closely associated with the genus Cyanothece (Synechococcaceae, chroococcales). Applied and Environmental Microbiology 77: 5888–5896.

Naselli-Flores, L., 2003. Man-made lakes in Mediterranean semi-arid climate: the strange case of Dr Deep Lake and Mr Shallow Lake. Hydrobiologia 506–509: 13–21.

Olds, B. P., B. C. Peterson, K. D. Koupal, K. M. Farnsworth-Hoback, C. W. Schoenebeck, & W. Wyatt Hoback, 2011. Water quality parameters of a Nebraska reservoir differ between drought and normal conditions. Lake and Reservoir Management 27: 229–234.

Padisák, J., 1997. Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Woloszynska) Seenayya et Subba Raju, an expanding, highly adaptive cyanobacterium: worldwide distribution and review of its ecology. Archiv Für Hydrobiologie Supplementband Monographische Beitrage 107: 563–593.

Padisák, J., L. O. Crossetti, & L. Naselli-Flores, 2009. Use and misuse in the application of the phytoplankton functional classification: a critical review with updates. Hydrobiologia 621: 1–19.

Paerl, H. W., 1988. Nuisance phytoplankton blooms in coastal, estuarine, and inland waters. Limnology and Oceanography 33: 823–843.

Paerl, H. W., 2017. Controlling harmful cyanobacterial blooms in a climatically more extreme world: management options and research needs. Journal of Plankton Research 39: 763–771.

Paerl, H. W., 2018. Mitigating toxic planktonic cyanobacterial blooms in aquatic ecosystems facing increasing anthropogenic and climatic pressures. Toxins 10: 1–16.

Paerl, H. W., P. T. Bland, N. D. Bowles, & M. E. Haibach, 1985. Adaptation to high-intensity, low-wavelength light among surface blooms of the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. Applied and environmental microbiology 49: 1046–1052.

Paerl, H. W., K. E. Havens, N. S. Hall, T. G. Otten, M. Zhu, H. Xu, G. Zhu, & B. Qin, 2020. Mitigating a global expansion of toxic cyanobacterial blooms: confounding effects and challenges posed by climate change. Marine and Freshwater Research 71: 579–592.

Paerl, H. W., & J. Huisman, 2008. Climate: blooms like it hot. Science 320: 57–58.

Paerl, H. W., & T. G. Otten, 2013. Harmful cyanobacterial blooms: causes, consequences, and controls. Microbial Ecology 65: 995–1010.

Paerl, H. W., & T. G. Otten, 2016. Duelling “CyanoHABs”: Unravelling the environmental drivers controlling dominance and succession among diazotrophic and non-N2-fixing harmful cyanobacteria. Environmental Microbiology 18: 316–324.

Paterson, M. J., D. W. Schindler, R. E. Hecky, D. L. Findlay, & K. J. Rondeau, 2011. Comment: Lake 227 shows clearly that controlling inputs of nitrogen will not reduce or prevent eutrophication of lakes. Limnology and Oceanography. 56, 1545–1547.

Pinto, T. da S., & V. Becker, 2015. Diel dynamic of phytoplankton functional groups in a tropical water supply, Extremoz Lake, northeastern Brazil. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 26: 356–366.

R Core Team, 2018. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna.

Reynolds, C. S., 1992. Eutrophication and the management of planktonic algae: what Vollenweider couldn’t tell us. In Sutcliffe, D. W., & J. G. Jones (eds), Eutrophication: Research and Application to Water Supply. The Freshwater Biological Association, Ambleside, Cumbria, 4–29.

Reynolds, C. S., 2006. The ecology of phytoplankton. The Ecology of Phytoplankton. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Reynolds, C. S., V. Huszar, C. Kruk, L. Naselli-Flores, & S. Melo, 2002. Towards a functional classification of the freshwater phytoplankton. Journal of Plankton Research 24: 417–428.

Rigosi, A., C. C. Carey, B. W. Ibelings, & J. D. Brookes, 2014. The interaction between climate warming and eutrophication to promote cyanobacteria is dependent on trophic state and varies among taxa. Limnology and Oceanography 59: 99–114.

Rocha Junior, C. A. N., M. R. A. Costa, R. F. Menezes, J. L. Attayde, & V. Becker, 2018. Water volume reduction increases eutrophication risk in tropical semi-arid reservoirs. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 30: e106.

Rook, J. J., 1974. Formation of haloforms during chlorination of natural watersitle. Water Treatment and Examination 23: 234–243.

Salmaso, N., A. Boscaini, C. Capelli, & L. Cerasino, 2018. Ongoing ecological shifts in a large lake are driven by climate change and eutrophication: evidences from a three-decade study in Lake Garda. Hydrobiologia 824: 177–195.

Schindler, D. W., R. E. Hecky, D. L. Findlay, M. P. Stainton, B. R. Parker, M. J. Paterson, K. G. Beaty, M. Lyng, & S. E. M. Kasian, 2008. Eutrophication of lakes cannot be controlled by reducing nitrogen input: Results of a 37-year whole-ecosystem experiment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 11254–11258.

SEMARH, 2017. State Secretariat of Environment and Water Resources. [available on ineternet at http://www.semarh.rn.gov.br/].

Soares, M. C. S., V. L. M. Huszar, M. N. Miranda, M. M. Mello, F. Roland, & M. Lürling, 2013. Cyanobacterial dominance in Brazil: distribution and environmental preferences. Hydrobiologia 717: 1–12.

Soares, M. C. S., M. I. D. A. Rocha, M. M. Marinho, S. M. F. O. Azevedo, C. W. C. Branco, & V. L. M. Huszar, 2009. Changes in species composition during annual cyanobacterial dominance in a tropical reservoir: physical factors , nutrients and grazing effects. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 57: 137–149.

Sukenik, A., O. Hadas, A. Kaplan, & A. Quesada, 2012. Invasion of nostocales (cyanobacteria) to subtropical and temperate freshwater lakes – physiological, regional, and global driving forces. Frontiers in Microbiology Frontiers 3: 86.

Thornton, J. A., & W. Rast, 1993. A Test of Hypotheses Relating to the Comparative Limnology and Assessment of Eutrophication in Semi-Arid Man-Made Lakes. Comparative Reservoir Limnology and Water Quality Management Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht 1–24.

Tilahun, S., & D. Kifle, 2019. The influence of El Niño-induced drought on cyanobacterial community structure in a shallow tropical reservoir (Koka Reservoir, Ethiopia). Aquatic Ecology 53: 61–77.

Torres, C. de A., M. Lürling, & M. M. Marinho, 2016. Assessment of the effects of light availability on growth and competition between strains of Planktothrix agardhii and Microcystis aeruginosa. Microbial Ecology 71: 802–813.

Uhelinger, V., 1964. Étude statistique des méthodes de dénobrement planctonique. Archives Sciences 17: 121–123.

Utermöhl, H., 1958. Zur vervollkommung der quantitativen phytoplankton: methodik. Mitteilungen der Internationale Vereinigung fürTheoretische und Angewandte Limnologie, 9: 1–38.

Valderrama, J. C., 1981. The simultaneous analysis of total nitrogen and total phosphorus in natural waters. Marine Chemistry 10: 109–122.

Visser, P. M., J. M. H. Verspagen, G. Sandrini, L. J. Stal, H. C. P. Matthijs, T. W. Davis, H. W. Paerl, & J. Huisman, 2016. How rising CO2 and global warming may stimulate harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Harmful Algae 54: 145–159.

Walter, J. M., F. A. C. Lopes, M. Lopes-Ferreira, L. M. Vidal, L. Leomil, F. Melo, G. S. de Azevedo, R. M. S. Oliveira, A. J. Medeiros, A. S. O. Melo, C. E. De Rezende, A. Tanuri, & F. L. Thompson, 2018. Occurrence of harmful cyanobacteria in drinking water from a severely drought-impacted semi-arid region. Frontiers in Microbiology 9: 176.

Wetzel, R., & G. Likens, 2000. Limnological Analyses. Springer Verlag, New York.

Wintermans, J. F. G. M., & A. De Mots, 1965. Spectrophotometric characteristics of chlorophylls a and b and their phenophytins in ethanol. BBA - Biophysics Including Photosynthesis 109: 448–453.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. The Graduate Program in Ecology/UFRN (Programa de Pós‐Graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte and Instituto de Gestão das Águas do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte (IGARN) supported this research. The authors are grateful to Dr. José Luiz Attayde for his support and project coordination. Also special gratitude to Edson Santana (fieldwork), Walter Santos (laboratory analyses), Julie Andrade (assistance with biovolume), Ewaldo Leitão (review and comments) and Prof. Dr. Judit Padisák for all support.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Pannonia. Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. The Graduate Program in Ecology/UFRN (Programa de Pós‐Graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte and Instituto de Gestão das Águas do Estado do Rio Grande do Norte (IGARN) supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

The author's consent for the publication.

Additional information

Handling editor: Luigi Naselli-Flores

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vanderley, R.F., Ger, K.A., Becker, V. et al. Abiotic factors driving cyanobacterial biomass and composition under perennial bloom conditions in tropical latitudes. Hydrobiologia 848, 943–960 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04504-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04504-7