Abstract

Mosquitoes represent a key threat for millions of humans worldwide, since they act as vectors for malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, Zika virus, filariasis, and encephalitis. In this study, we tested chitosan-synthesized silver nanoparticles (Ch–AgNP) using male crab shells as a source of chitosan, which acted as a reducing and capping agent. Ch–AgNP were characterized by UV–Vis spectroscopy, FTIR, SEM, EDX, and XRD. Chitosan and Ch–AgNP were tested against larvae and pupae of the malaria vector Anopheles sundaicus under laboratory and field conditions. Antibacterial properties of Ch–AgNP were tested on Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus vulgaris using the agar disk diffusion assay. The standard predation efficiency of the mosquito natural enemy Carassius auratus in laboratory conditions was 60.80 (on larva II) and 19.68 individuals (on larva III) per day, while post-treatment with sub-lethal doses of Ch–AgNP, the predation efficiency was boosted to 72.00 (on larva II) and 25.80 individuals (on larva III). Overall, Ch–AgNP fabricated using chitosan extracted from the male crab shells of the hydrothermal vent species Xenograpsus testudinatus may offer a novel and safer control strategy against A. sundaicus mosquito vectors, as well as against Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mosquitoes are responsible for the transmission of numerous infectious diseases including malaria, dengue fever, yellow fever, Zika virus, filariasis, and different types of encephalitis. Malaria is transmitted by Anopheles mosquitoes and leads to high mortality rates predominantly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (Walker et al., 2014; Benelli, 2015a, b; Benelli & Mehlhorn, 2016). Malaria continues to be a major global health threat despite more than 100 years of research since the discovery of malaria parasites in human blood by Charles Laveran in 1880. Later, the causal connection of mosquito vectors and the transmission of malaria was made by Sir Ronald Ross in 1898 (Cox, 2010). Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites, vectored to vertebrates through the bites of infected Anopheles mosquitoes, which mainly bite between dusk and dawn (Mehlhorn, 2008; Ward & Benelli, 2017). According to the latest estimates, there were about 198 million cases of malaria in 2013 and estimated as 584,000 deaths. Most of the death occurs among children living in Africa, where a child dies every minute from malaria (WHO, 2014; Benelli et al., 2016). Under the paucity of vaccines and preventive drugs, malaria control programs are increasingly dependent on vector control. Currently, the main control tool against mosquito larvae is represented by treatments with organophosphates, insect growth regulators, and microbial control agents (Benelli, 2015a; Murugan et al., 2015a, b, c). In recent years, many organic products, including plant extracts, essential oils, and isolated constituents have been proposed for eco-friendly control mosquito vectors and other blood-sucking arthropods (Sukumar et al., 1991; Azizi et al., 2014; Benelli, 2015b; Govindarajan & Benelli, 2016a, b, c).

Chitosan or chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide on the planet (Gooday, 1990). Chitosan is widely present in many animal tissues, including the exoskeletons of arthropods, the beaks of cephalopods, the eggs and gut linings of nematodes (Gohel et al., 2006), but even in fungi (Castro & Paulin, 2012), and spines of diatoms (Bartnicki-Garcia & Lippman, 1982). Chitosan is characterized by no toxicity to vertebrates, high mechanical strength, susceptibility to chemical modifications, and cost-effective availability. This has attracted many applications (Sorlier et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2010), such as wound-healing agents, drug carriers, chelating agents, membrane filters for water treatment, and biodegradable coating or film for food packaging. It is also used as a potential biomaterial for nerve repair, as food preservative agent, and in non-viral gene delivery (Gow & Gooday, 1983). In addition, several studies on the antimicrobial activity of chitosan and its derivatives against plant pathogens and pests have been conducted (Rabea et al., 2005; Badawy, 2010; Kaur et al., 2012; El-Mohamedy et al., 2014). A chitin derivative (N-(2-chloro-6-fluorobenzyl-chitosan) led to 100% mortality of larvae of the cotton leaf worm Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval, 1833). While chitosan treatments have been found to be moderately effective against vector pests and herbivorous insects, it has also been used successfully as an ingredient in the artificial diet used for predatory, carnivorous insects reared for the biological control of arthropod pests (Tan et al., 2010). This finding suggests that chitin-based products could potentially be less harmful to non-target insects if compared to conventional insecticides.

Mosquito larval population can also be controlled by many aquatic predators, including water bugs, tadpoles, crabs, copepods, and fishes (Bowatte et al., 2013; Kalimuthu et al., 2014). Among the latter, a good example is Carassius auratus (Linnaeus, 1758). Goldfish are among the most popular fishes in the pet trade and are widely established throughout the United States and southern Canada (Lee et al., 1980; Page & Burr, 1991). Also, mosquito fishes are easy to culture in laboratory settings as well as in the field, and have been widely used to evaluate the non-target impacts of mosquitocidals (Rao & Kavitha, 2010; Patil et al., 2012b; Murugan et al., 2015d). Carassius auratus auratus Linnaeus, 1758 is a small-sized member of the freshwater family Cyprinidae (carps and minnows), typically reaching about 22 cm in length. There are several subspecies of C. auratus, which are all indigenous to Asia, including C. auratus auratus (Vietnam), C. auratus buergeri Temminck & Schlegel, 1846, C. auratus grandoculis Temminck & Schlegel, 1846, and C. auratus langsdorfii (Japan) (Chandramohan et al., 2016).

The “green synthesis” of silver nanoparticles (AgNP) is considered an eco-friendly technology leading to a reduction in the employment or generation of hazardous substances (Banerjee et al., 2014; Benelli, 2016a, b). Nanoparticles may cover a vast application in pharmaceutical, industrial, and biotechnological fields (Suman et al., 2013; Arokiyaraj et al., 2015). In recent years, nanoparticle composites have become important owing to their small size and large surface area and because they exhibit unique properties not seen in bulk materials with useful applications in photovoltaic cells, optical and biological sensors, conductive materials, and coating formulations (Templeton et al., 2000). Silver ions and silver-based compounds are highly toxic to microorganisms, including important species of pathogen bacteria (Zhao & Stevens, 1998). Therefore, AgNP have emerged with diverse medical applications including silver-based dressings and silver-coated medicinal devices, such as nano-gels and nano-lotions (Rai et al., 2009). In addition, recent research showed the high efficacy of green-synthesized AgNP also in the fight against malaria vectors (Arokiyaraj et al., 2015; Muthukumaran et al., 2015; Govindarajan et al., 2016a, b), even in the field (Dinesh et al., 2015).

In this scenario, the present study was carried out to develop chitosan-fabricated AgNP; nanoparticles were characterized using UV–Vis spectroscopy, Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The multipurpose biological activity of chitosan-synthesized AgNP was studied in the following experiments (a) evaluation of the larvicidal and pupicidal potential of AgNP against the costal malaria vector Anopheles sundaicus (Rodenwaldt, 1925); (b) assessment of the predatory efficiency of the goldfish C. auratus against larval of A. sundaicus, in normal laboratory conditions, and in a nanoparticle-contaminated aquatic environment, (c) investigation of the nanoparticle antibacterial activity on Gram-positive and Gram-negative human pathogenic bacteria.

Materials and methods

Collection of crab shells and processing

Hydrothermal vent crab Xenograpsus testudinatus Ng, Huang & Ho, 2000 (Decapoda: Brachyura) were collected from shallow hydrothermal vents at the NE Taiwan coast. The exoskeletons were placed in Ziploc bags and frozen overnight and then subsequently cut into smaller pieces using a meat tenderizer. Wet samples of 10 g of crushed crab exoskeletons were placed on foil paper and measured using a metal balance, with five replications. The labeled samples were then oven-dried at 65°C for four consecutive days until they obtained constant weight. The dry weight of the samples was then determined, and the moisture content was also measured based on the differences between wet and dry weight.

Chitosan recovery from crab shell

The chitosan production from native chitin involves washing of crushed crab exoskeletons in distilled water. Crushed crab exoskeletons were placed in 1,000 ml beakers and soaked in boiling sodium hydroxide (2 and 4% w/v) for 1 h to dissolve the proteins and sugars thus isolating the crude chitin. Sodium hydroxide (4% NaOH) was used for chitin preparation, a concentration used at Sonat Corporation (Lertsutthiwong et al., 2002). After boiling the samples in sodium hydroxide, the beakers containing the shell samples were removed from the hot plate, and allowed to cool for 30 min at room temperature (Lamarque et al., 2005). The exoskeletons were then further crushed to pieces of 0.5–5.0 mm using a meat tenderizer (Murugan et al., 2016).

Demineralization

The grinded exoskeletons were demineralized using 1% HCl at four times its quantity. The samples were soaked for 24 h to remove the minerals (mainly calcium carbonate) (Trung et al., 2006). The demineralized crab shell powder was then treated for 1 h with 50 ml of a 2% NaOH solution to decompose the albumen into water-soluble amino acids. The remaining chitin was washed with deionized water, which was then drained off. The chitin was further converted into chitosan by the process of deacetylation (Huang et al., 2004; Murugan et al., 2016).

Deacetylation

Deacetylation process was carried out by adding 50% NaOH and then boiled at 100°C for 2 h on a hot plate. The samples were then placed under a hood and cooled for 30 min at room temperature. Afterwards, the samples were washed continuously with 50% NaOH and filtered in order to retain chitosan as solid matter. The samples were then left uncovered and oven-dried at 110°C for 6 h. The obtained chitosan then turned into cream-white in color (Muzzarelli & Rochetti, 1985).

Biosynthesis of nanoparticles

Following the method by Murugan et al. (2016), 2 g of chitosan powder was taken in a 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks filled with 100 ml of double distilled water. The mixture was boiled for 20 min and filtered using Whatman filter paper no. 1, stored at −15°C and tested within 5 days. The filtrate was treated with aqueous 1 mM AgNO3 solution in an Erlenmeyer flask and incubated at room temperature. A reddish brown suspension indicated the formation of AgNP, since aqueous silver ions were reduced by chitosan powder and thus generating stable chitosan–silver nanocomposite in water.

Characterization of nanoparticles

The presence of bio-synthesized AgNP was confirmed by sampling the reaction mixture at regular intervals, and the absorption maxima were scanned by UV–Vis, at a wavelength of 300–800 nm in a UV-3600 Shimadzu spectrophotometer at 1-nm resolution. Furthermore, the reaction mixture was subjected to centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 20 min, and the resulting pellet was dissolved in deionized water and filtered through a Millipore filter (0.45 μm). The structure and composition of AgNP were analyzed by using a 10-kV ultrahigh-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM); 25 μl of the sample was sputter-coated on a SEM. Surface groups of nanoparticles were qualitatively confirmed by using FTIR spectroscopy (Stuart, 2002) with spectra recorded by a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 2000 FTIR spectrophotometer. In addition, XRD and EDAX were also analyzed for the presence of metals in the sample.

Tested organisms

The eggs of A. sundaicus were collected (using an ‘O’ type brush) from drinking water containers available in coastal areas of Velankanni (79.8°E, 10.7°N) and Nagapattinam (79.8°E, 10.7°N), Tamil Nadu, southeastern part of India, using a "O"-type brush, and emerging specimens were identified following Gaffigan et al. (2015). Batches of 100–110 eggs were transferred to 18 cm × 13 cm × 4 cm enamel trays containing 500 ml of water, where eggs were allowed to hatch at laboratory conditions (27 ± 2°C and 75–85% RH; 14:10 (L/D) photoperiod). Anopheles sundaicus larvae were fed daily 5 g of ground dog biscuits (Pedigree, USA) and hydrolyzed yeast (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) at 3:1 ratio.

Mosquitocidal potential at laboratory conditions

The mosquitocidal activity of AgNPs against An. sundaicus was assessed as described by Amerasan et al. (2016) and Murugan et al. (2015c). 25 An. sundaicus larvae (I, II, III, or IV instar) or pupae were placed in 500-ml beakers and exposed for 24 h to dosages of 25, 50, 75, 100, and 125 ppm (chitosan) and 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 ppm (Cs–Ag nanoparticles). A 0.5-mg larval food was provided for each test concentration. Control mosquitoes were exposed for 24 h to the corresponding concentration of the sample. For each experiment, three replicates were made and percentage mortality was calculated as follows:

Mosquitocidal potential in the field

Mosquitocidal activity of AgNP against An. sundaicus in field conditions was evaluated by applying six water reservoirs at the National Institute of Communicable Disease Centre (Coimbatore, India), using a knapsack sprayer (Private Limited 2008, Ignition Products, Town, India). Pretreatment and post-treatments at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h were conducted using a larval dipper. Toxicity was assessed against third and fourth instar larvae. Larvae were counted and identified to specific level. More than 80% of all surveyed larvae belonged to A. sundaicus (Gaffigan et al., 2015). Six trials were conducted for each test site at similar weather conditions (27 ± 2°C; 79% R.H.). The required quantity of mosquitocidal was calculated based on the total surface area and volume (0.25 m3 and 250 l); the required concentration was prepared using 10 × LC50 values (Murugan et al., 2003; Suresh et al., 2015). Percentage reduction of the larval density was calculated using the formula:

where C is the total number of mosquitoes in the control and T is the total number of mosquitoes in the treatment.

Antibacterial potential

AgNP (1.0 mg) were dissolved in 2 ml of 1.0% (W/V) aqueous acetic acid solution. From this 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, and 1.0 ml was taken and made up to 1.0 ml by adding 1% acetic acid to prepare various concentrations containing 100, 150, 200, and 250 µg of AgNP sample. The bacterial species, namely Bacillus subtilis Cohn, 1872, Escherichia coli (Migula, 1895) Castellani and Chalmers, 1919, Klebsiella pneumoniae (Schroeter, 1886) Trevisan, 1887 and Proteus vulgaris Hauser, 1885, used in this study were purchased from the Microbial Type Culture Collection and Gene Bank Institute of Microbial Technology Sector 39-A, Chandigarh-160036 (India). Four selective species were incubated in the nutrient broth and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 24 h. Nutrient agar medium was also prepared, autoclaved, and transformed aseptically into sterile Petri dishes. On this, 24-h-old bacterial broth cultures were inoculated by using a sterile cotton swab. An in vitro antibacterial assay was carried out by the disk diffusion technique (Bauer et al., 1966) on Whatman filter paper no. 1 disks with 4-mm diameter were impregnated with known amounts of test samples. The disks were loaded each with 10 μl of the extract by first applying 5 μl with the pipette, allowing evaporation, and then applying another 5 μl, then drying again. The petri plates were kept for incubation at room temperature (27°C ± 2) for 24 h. After incubation, plates were observed for zones of inhibition (mm) measured using a photomicroscope (Leica ES2, Dresden, Germany) and compared with standard tetracycline positive control (Jaganathan et al., 2016).

Impact on gold fish predation

As a control, the predation efficiency of gold fish, C. auratus, was assessed against A. sundaicus larvae under standard laboratory conditions. For each instar, 500 mosquitoes were introduced, with 1 fish, in a 500-ml glass beaker containing 250 ml of dechlorinated water. Mosquito larvae were replaced daily with new ones. For each mosquito instar, four replicates were conducted. A control was used of 250 ml dechlorinated water. All beakers were checked after 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days and the number of larval prey consumed by fishes was recorded. Predatory efficiency was calculated using the following formula:

In a second experiment, the predation efficiency of golden fish, C. auratus, was assessed against A. sundaicus larvae, after a mosquitocidal treatment with Cs–AgNP. For each instar, 500 mosquitoes were introduced with 1 fish in a 500-ml glass beaker filled with 249 ml of dechlorinated water and 1 ml of the desired concentration of Cs–AgNP (2 ppm, i.e., about 1/3 of the LC50 calculated against first instar larvae of A. sundaicus). Mosquito larvae were replaced daily with new ones. For each mosquito instar, four replicates were conducted. Control was 250 ml of water. All beakers were checked after 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 days and the number of preys consumed larvae by fishes was recorded. Predatory efficiency was calculated using the above-mentioned formula (Subramaniam et al., 2015, 2016).

Data analysis

Larvicidal and pupicidal data were subjected to probit analysis. LC50 and LC90 were calculated using the method by Finney (1971). Chi square values were not significant (Benelli, 2017). Fish predation data were analyzed by JMP 7 using a weighted general linear model with one fixed factor: y = ax + b where y is the vector of the observations (the number of consumed prey), a is the incidence matrix, x is the vector of fixed effect (the targeted mosquito instar), and b is the vector of the random residual effect. A probability level of P < 0.05 was used for the significance of differences between values. All experiments were repeated at least three times. The statistical software SPSS version 16.0 was used for performing the analyses. The P values < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Larvicidal and pupicidal toxicity against A. sundaicus in the laboratory and field conditions

In laboratory conditions, chitosan was toxic against A. sundaicus larvae and pupae, even at low concentrations, LC50 values after 24 h exposure ranged from 50.763 (larva I) to 100.051 ppm (pupae), respectively (Table 1). Chitosan-fabricated AgNP were highly toxic against A. sundaicus with LC50 values ranging from 7.186 ppm (larva I) to 14.665 ppm (pupae) (Table 2), respectively. The field applications of chitosan (10 × LC50) lead to the larval reduction of A. sundaicus by 75.33, 42.50, and 100% after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively, while chitosan-fabricated AgNP (10 × LC50) lead to 63.66, 29.83, and 100% of larval reduction (Table 3).

Impact of chitosan-fabricated AgNP on goldfish predation

We observed no detrimental impacts on goldfish predation, as well as no mortality in treated goldfish during the whole study period. Under standard laboratory conditions, C. auratus actively predates on A. sundaicus larval instars. The percentages of predation were given in Table 4. In the AgNP-contaminated environment (2 ppm), predation rates reached 82.88% on first instar larvae, as described in Table 4.

Antibacterial activity

In agar disk diffusion assays, chitosan-synthesized AgNP showed good antibacterial effect against B. subtilis, E. coli, K. pneumoniae and P. vulgaris (Table 5). AgNP tested at 100 ppm provided growth inhibition zones larger than 13 mm of all tested bacteria, while inhibition zones reached 17 mm on E. coli when AgNP were tested at 250 ppm (Table 5).

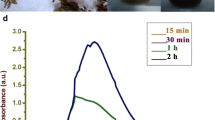

Characterization of chitosan-synthesized silver nanoparticles

UV–Vis absorption spectrum of Cs–AgNP is shown in Fig. 1, where 426 nm was the maximum absorption peak. Figure 2 shows various stretching frequency peaks in the FTIR spectrum of chitosan-fabricated AgNP. The surface morphology of chitosan-fabricated AgNP was analyzed using the FESEM. FESEM of chitosan–silver nanoparticles shows spherical-shaped particles (Fig. 3) and the size of the particles ranged from 30 to 50 nm. EDX spectrum recorded from chitosan-fabricated AgNP showed a strong Ag signal, confirming the presence of metallic silver (Fig. 4). The crystalline nature of chitosan-fabricated AgNP was showed by XRD pattern as depicted in Fig. 5. Chitosan can exhibit two crystalline structures, and many diffraction patterns observed by XRD typically represent mixtures of the two forms. The XRD pattern of pure chitosan exhibits a strong characteristic peak at about 2θ = 20° for chitosan.

Discussion

From the toxicity results, we noted that early instar mosquito larvae were more susceptible to the exposure of chitosan-fabricated AgNP over the later ones; simultaneously, pupae were not much affected by chitosan-fabricated AgNP. These results are comparable to previous reports studying green pesticides on mosquitoes (Prasanna Kumar et al., 2012), demonstrating the toxic effects of methanolic extracts of Sargassum wightii Greville ex J.Agardh, 1848, together with the microbial insecticide from Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis Berliner, 1915 against A. sundaicus, with LC50 values of 0.88% (I instar), 0.73% (II instar), 1.34% (III instar), 1.56% (IV instar), and 1.71% (pupae). Regarding chitosan toxicity on arthropod pests, besides our earlier research on mosquito vector control (Murugan et al., 2016), Sahab et al. (2015) studied the effect of nano-chitosan against eggs of Aphis gossypii Glover, 1877, under laboratory and under semi-field conditions. Furthermore, Mohamed et al. (2012) elucidated the toxicity of chitosan compounds on larval mortality, growth inhibition, and antifeedant activity against III instar larvae of S. littoralis. Sabbour (2013) noted the insecticidal activity of chitosan against various aphids at a concentration ranging from 600 to 6,000 mg/l. In addition, chitosan exhibited a 70–80% insecticidal activity against aphid pests Rhopalosiphum padi (Linnaeus, 1758), Metopolophium dirhodum (Walker, 1849), and A. gossypii (Zhang et al., 2003). Furthermore, chitosan of different molecular weights and chitosan–metal complexes showed significant mortality against Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe, 1841 (Badawy & EI-Aswad, 2012).

The effect of chitosan-fabricated AgNP against A. sundaicus was comparable with the toxicity of Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschnikoff) Sorokin, 1882-synthesized AgNP against the rural malaria vector A. culicifacies, with LC50 values of 28.3 ppm (I instar), 35.1 ppm (II), 41.2 ppm (III), 47.1 ppm (IV), and 54.8 ppm (pupae) (Amerasan et al., 2016). Furthermore, Datura metel L. leaf- fabricated AgNP were also found toxic against A. stephensi at very low doses (Murugan et al., 2015b). Aristolochia indica L.-synthesized AgNP showed LC50 ranging from 3.94 (I) to 15.65 ppm (pupae) towards A. stephensi (Murugan et al., 2015a). The larvicidal potential of chitosan-fabricated AgNP may be linked to structural deformations evoked by nanoparticles on DNA (Feng et al., 2000) and digestive tract enzymes, as well as by the generation of reactive oxygen species (Patil et al., 2012a). The broad larvicidal spectrum of chitosan-fabricated AgNP may also be due to a synergistic combination of AgNP and chitosan-borne capping agents, which adhere to elemental silver during the reduction and stabilization of AgNP (Benelli, 2016b).

The effectiveness of chitosan-fabricated AgNP has been elucidated also in the field. In agreement with our work, Panneerselvam et al. (2013a) reported that the leaf extract of Euphorbia hirta L. was highly effective in field trials against A. stephensi, as it led to larval density reductions of 13.17, 37.64, and 84.00% after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. Recently, Suresh et al. (2015) reported that the field application of Phyllanthus niruri L. extract (10 × LC50) leads to a larval reduction in Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus in Hasselquist, 1762) of 39.9, 69.2, and 100%, after 24, 48, and 72 h, respectively. In case of chitosan-fabricated AgNP, we hypothesize that the high mortality rates exerted against A. sundaicus may be mainly due to the small size of AgNP, which allowed these nanoparticles to pass through the insect cuticle and even into individual cells, where they interfere with molting and other physiological processes (Madhiyazhagan et al., 2015; Subramaniam et al., 2015). In addition, for silica NP, the mode of action for insecticidal activity has been reported through the desiccation of the insect cuticle by physicosorption of lipid and is also expected to cause damage in the cell membrane, resulting in cell lysis and death of the insects (Tiwari & Behari, 2009).

From a non-target perspective, we observed no detrimental impact on goldfish predation, as well as no mortality in treated goldfish during the whole study period. However, Chobu et al. (2015) observed that the mosquitofish Gambusia affinis Baird and Girard, 1853 is an efficient predator of A. gambiae third instar larvae if compared to C. auratus. Recently, Chandramohan et al. (2016) noted that the predation efficiency of the goldfish, C. auratus, was rather high against II and III instar larvae of A. aegypti. In agreement with our results, Pergularia daemia (Forssk.) Chiov.-synthesized AgNP have been reported as non-toxic against the non-target fish Poecilia reticulata Peters, 1859, whereas they are able to provide substantial mortality rates against the mosquito vectors A. stephensi and A. aegypti (Patil et al., 2012c). Furthermore, Twu et al. (2008) did not find any toxicity effects of Vinca rosea (synonyms: Catharanthus roseus (L.) G.Don, 1837)-synthesized AgNP against P. reticulata after 72 h of exposure to concentrations toxic against A. stephensi and Culex quinquefasciatus Say, 1823. Recently, Subramaniam et al. (2015) reported that Mimusops elengi L.-synthesized AgNP did not affect predation rates of the mosquitofish G. affinis against A. stephensi and A. albopictus.

We also showed good antimicrobial effectiveness of chitosan-fabricated AgNP. Very recently, comparable results have been obtained while testing Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f.-synthesized AgNP against these three bacterial species (dose: 300 ppm), where A. vera-fabricated AgNP led to zones of inhibition higher than 19 mm in all tested bacteria (Dinesh et al., 2015). Furthermore, Jaganathan et al. (2016) reported that the earthworm-synthesized AgNPs showed good antibacterial properties against B. subtilis, K. pneumoniae, and Salmonella typhi Le Minor and Popoff, 1987. Also, plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss showed appreciable antibacterial efficacy against three bacteria, K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Staphylococcus aureus Rosenbach 1884 (Roy et al., 2015).

Concerning the biophysical characterization of chitosan-fabricated AgNP, the characteristic UV absorption peak at 426 nm for chitosan and AgNP in the present study was comparable with the other researchers recording it at a range of 410–420 nm (Chen et al., 2007; Murugadoss & Chattopadhyay, 2008; Sanpui et al., 2008; Twu et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2009). Comparing the results of UV–Vis absorption spectra, the characteristic SPR band center of the Cs–AgNP composites was observed at about 417 nm, because chitosan can interact with silver ions originating from the amino and hydroxyl groups present in the β-1,4-glucosamine units of the polymer (Wazed Ali et al., 2001).

FTIR spectroscopy was carried out to identify the biomolecules responsible of the reduction of Ag+ ions to AgNP as well as of capping of the bio-reduced AgNP synthesized using chitosan. The FTIR spectrum of the present study showed some differences if compared to the earlier FTIR report by Murugan et al., (2016). However it was comparable with the reports by Govindan et al. (2012) who has shown major peak at 3,441 and 2,929 cm−1 and N–H bending at 1,639 cm−1. The FTIR spectrum of chitosan shows O–H stretching at 3,433 cm−1, C–H and C–N stretching at 2,920 cm−1, N–H bending at 1,647 cm−1, N–H angular deformation in the CO–NH plane at 1,536 cm−1, and C–O–C band stretching at 1,109 cm−1 which matches well with the reports by Saraswathy et al., (2001) and Wazed Ali et al., (2001). The spectra of Ag/chitosan composites exhibited a few alternations in comparison with that of chitosan. The characteristic bands of chitosan at 1,658 and 1,600 cm−1, corresponding to the stretching vibrations of amide C–O bonds, shifted to 1,628 cm−1 with a significant decrease of transmittance in this band region. Additionally, the intensity of the O–H and N–H stretching band at 3,434 cm−1 originated from the hydroxyl and primary amino groups decreasing and shifting to 3,426 cm−1, suggesting the chelation of Ag with both amino and hydroxyl groups of chitosan (Chen et al., 2014). Furthermore, many peaks of chitosan were observed which shows a broad-OH stretching absorption band between 3,450 and 3,100 cm−1. Another major absorption band was between 1,220 and 1,020 cm−1 that represents the free amino group (–NH2) at C2 position of glucosamine, a major peak present in chitosan. The peak at 1,384 cm−1 represents the –C–O stretching of the primary alcoholic group. The peak at 1,184 cm−1 is due to a ketone group present in the isoniazid (Muhammed Rafeeq et al., 2010).

Chitosan-fabricated AgNP show a mixture of chitosan and Ag, whereas the AgNP are enveloped by a chitosan polymer (Yoshizuka et al., 2000). The chitosan-fabricated AgNP FESEM image shows spherically shaped particles (see also Govindan et al., 2012). SEM micrographs of chitosan-fabricated AgNP illustrate the formation of defined nanostructures of Ag in the chitosan matrices (Fig. 3). This indicates that AgNP are formed along with the polymer chains rather than just by entrapment of Ag in the gel matrix (Krishna Rao et al., 2012). Chitosan-fabricated AgNP-treated E. tarda showed a gradual increase of structural damage on surface and cell morphology with increasing concentrations of AgNP at 12.5, 25, and 50 μg/ml during a 6-h incubation period (Dananjaya et al., 2014). Our samples showed an optical absorption peak at 3 keV due to the surface plasmon resonance, which is typical of Ag nanostructures (Magudapathy et al., 2001; Fayaz et al., 2010; Kaviya et al., 2011). Furthermore, EDX also showed the presence of Ca, Si, O, and Mg, suggesting that mixed precipitates were present in the chitosan (Usha & Rachel, 2014). With reference to XRD results, chitosan shows two diffraction peaks, one at 2θ = ~10° corresponding to the (010) diffraction plane of the crystalline structure I of chitosan (Julkapli et al., 2009; Souza et al., 2010). XRD patterns of chitosan-fabricated AgNP synthesized with 0.04 and 0.06 M AgNO3 showed another peak at about 38°C, corresponding to Ag nanoparticles in addition to the chitosan at 20°C (Ruparelia et al., 2008; Ali et al., 2011).

Conclusions

This study explored the promising potential of chitosan-fabricated AgNP, a synthetic product obtained using shell powder from the hydrothermal vent crab X. testudinatus, in controlling the coastal malaria vector A. sundaicus. We present a detailed synthesis of chitosan-fabricated AgNP. The produced AgNP were hydrophilic, dispersed uniformly in water, and exhibited significant larvicidal as well as pupicidal activities against the vector A. sundaicus. The characterization results recorded from UV–Vis spectrophotometry, FESEM, XRD, and EDX analyses support the effective biosynthesis of chitosan-fabricated AgNP. This research highlighted that chitosan-fabricated AgNP are easy to produce, stable over time, and can be employed at low dosages to strongly reduce populations of the malaria vector, A. sundaicus, without detrimental effects on the predation of natural mosquito enemies, such as goldfishes. It also effectively inhibits important bacterial pathogens of public health relevance.

References

Ali, S. W., S. Rajendran & M. Joshi, 2011. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan and silver loaded chitosan nanoparticles for bioactive polyester. Carbohydrate Polymers 83: 438–446.

Amerasan, D., T. Nataraj, K. Murugan, P. Madhiyazhagan, C. Panneerselvam, P. Madhiyazhagan, M. Nicoletti & G. Benelli, 2016. Myco-synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Metarhizium anisopliae against the rural malaria vector Anopheles culicifacies Giles (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Pest Science 89: 249–256.

Arokiyaraj, S., V. D. Kumar, V. Elakya, T. Kamala, S. K. Park, M. Ragam, et al., 2015. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using floral extract of Chrysanthemum indicum L.—potential for malaria vector control. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22: 9759–9765.

Azizi, S., M. B. Ahmad, F. Namvar & R. Mohamad, 2014. Green biosynthesis and characterization of zinc oxide nanoparticles using brown marine macroalga Sargassum muticum aqueous extract. Materials Letters 116: 275–277.

Badawy, M. E. I., 2010. Structure and antimicrobial activity relationship of quaternary N-alkyl chitosan derivatives against some plant pathogens. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 117: 960–969.

Badawy, M. E. I. & A. F. EI-Aswad, 2012. Insecticidal activity of chitosons of different molecular weights and chitoson–metal complexes against cotton leaf sworm Spodoptera littoralis and oleander aphid Aphis neri. Plant Protection Science 48: 131–141.

Banerjee, P., M. Satapathy, A. Mukhopahayay & P. Das, 2014. Leaf extract mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from widely available Indian plants: synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial property and toxicity analysis. Bioresources and Bioprocessing 1: 1–10.

Bartnicki-Garcia, S. & E. Lippman, 1982. Fungal wall composition. In Laskin, A. J. & H. A. Lechevalier (eds), CRC Hand Book of Microbiology, 2nd ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton: 229–252.

Bauer, A. W., W. M. Kirby, J. C. Cherris & M. Truck, 1966. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. American Journal of Clinical Pathology 45: 493–496.

Benelli, G., 2015a. Research in mosquito control: current challenges for a brighter future. Parasitology Research 114: 2801–2805.

Benelli, G., 2015b. Plant-borne ovicides in the fight against mosquito vectors of medical and veterinary importance: a systematic review. Parasitology Research 114: 3201–3212.

Benelli, G., 2016a. Plant-mediated biosynthesis of nanoparticles as an emerging tool against mosquitoes of medical and veterinary importance: a review. Parasitology Research 115: 23–34.

Benelli, G., 2016b. Green synthesized nanoparticles in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases and cancer – a brief review. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 95: 58–68.

Benelli, G., 2017. Commentary: data analysis in bionanoscience—issues to watch for. Journal of Cluster Science 28: 11–14.

Benelli, G. & H. Mehlhorn, 2016. Declining malaria, rising of dengue and Zika virus: insights for mosquito vector control. Parasitology Research 115: 1747–1754.

Benelli, G., A. Lo Iacono, A. Canale & H. Mehlhorn, 2016. Mosquito vectors and the spread of cancer: an overlooked connection? Parasitology Research 115: 2131–2137.

Bowatte, G., P. Perera, G. Senevirathne, S. Meegaskumbura & M. Meegaskumbura, 2013. Tadpoles as dengue mosquito (Aedes aegypti) egg predators. Biological Control 67: 469–474.

Castro, S. P. M. & E. G. L. Paulin, 2012. Is chitosan a new panacea? Areas of application. In Karunaratne, D. N. (ed.), The Complex World of Polysaccharides. InTech, Rijeka.

Chandramohan, B., K. Murugan, C. Panneerselvam, P. Madhiyazhagan, R. Chandirasekar, D. Dinesh, P. M. Kumar, K. Kovendan, U. Suresh, J. Subramaniam, R. Rajaganesh, A. T. Aziz, B. Syuhei, M. S. Alsalhi, S. Devanesan, M. Nicoletti, H. Wei & G. Benelli, 2016. Characterization and mosquitocidal potential of neem cake-synthesized silver nanoparticles: genotoxicity and impact on predation efficiency of mosquito natural enemies. Parasitology Research 115: 1015–1025.

Chen, P., L. Song, Y. Liu & Y. Fang, 2007. Synthesis of silver nonoparticles by r-ray irradiation in acetic water solution containing chitosan. Radiation Physics Chemistry 76: 1165–1168.

Chen, Q., H. Jiang, H. Ye, J. Li & J. Huang, 2014. Preparation, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities of silver/chitosan composites. Journal of Carbohydrate Chemistry 33: 298–312.

Chobu, M., G. Nkwengulila, A. M. Mahande, B. J. Mwang’onde & E. J. Kweka, 2015. Direct and indirect effect of predators on Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto. Acta Tropica 142: 131–137.

Cox, F. E. G., 2010. History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors. Parasites & Vectors 3: 1–9.

Dananjaya, S. H. S., G. I. Godahewa, R. G. P. T. Jayasooriya, O. H. Chulhong, L. Jehee & D. Z. Mahanama, 2014. Chitosan silver nano composites (CAgNCs) as potential antibacterial agent to control Vibrio tapetis. Journal of Veterinary Science Technology 5: 209. doi:10.4172/2157-7579.1000209.

Dinesh, D., K. Murugan, P. Madhiyazhagan, C. Panneerselvam, M. Nicoletti, W. Jiang, G. Benelli, B. Chandramohan & U. Suresh, 2015. Mosquitocidal and antibacterial activity of green-synthesized silver nanoparticles from Aloe vera extracts: towards an effective tool against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi? Parasitology Research 114: 1519–1529.

El-Mohamedy, R. S., F. Abdel-Kareem, H. Jaboun-Khiareddine & M. Daami-Remadi, 2014. Chitosan and Trichoderma harzianum as fungicide alternatives for controlling Fusarium crown and root rot of tomato. Tunisian Journal of Plant Protection 9: 31–43.

Fayaz, M., K. Balaji, M. Girilal, R. Yadav, P. T. Kalaichelvan & R. Venketesan, 2010. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their synergistic effect with antibiotics: a study against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 6: 103–109.

Feng, Q. L., J. Wu, G. Q. Chen, F. Z. Cui & T. N. Kim, 2000. A mechanistic study of the antibacterial effect of silver ions on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 52: 662–668.

Finney, D. J., 1971. Probit analysis. Cambridge University Press, London: 68–72.

Gaffigan, T. V., R. C. Wilkerson, J. E. Pecor, J. A. Stoffer & T. Anderson, 2015. Systematic catalog of Culicidae. http://www.mosquitocatalog.org/.

Gohel, V., A. Singh, M. Vimal, P. Ashwini & H. S. Chhatpar, 2006. Bioprospecting and antifungal potential of chitinolytic microorganisms. African Journal of Biotechnology 5: 54–72.

Gooday, G. W., 1990. The ecology of chitin degradation. Advances in Microbial Ecology 11: 387–419.

Govindan, S., E. A. K. Nivethaa, R. Saravanan, V. Narayanan & A. Stephen, 2012. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan-silver nanocomposite. Applied Nanoscience 2: 299–303.

Govindarajan, M. & G. Benelli, 2016a. α-Humulene and β-elemene from Syzygium zeylanicum (Myrtaceae) essential oil: highly effective and eco-friendly larvicides against Anopheles subpictus, Aedes albopictus and Culex tritaeniorhynchus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitology Research 115: 2771–2778.

Govindarajan, M. & G. Benelli, 2016b. Eco-friendly larvicides from Indian plants: effectiveness of lavandulyl acetate and bicyclogermacrene on malaria, dengue and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vectors. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 133: 395–402.

Govindarajan, M. & G. Benelli, 2016c. Artemisia absinthium-borne com- pounds as novel larvicides: effectiveness against six mosquito vectors and acute toxicity on non-target aquatic organisms. Parasitology Research 115: 4649–4661.

Govindarajan, M., H. F. Khater, C. Panneerselvam & G. Benelli, 2016a. One- pot fabrication of silver nanocrystals using Nicandra physalodes: a novel route for mosquito vector control with moderate toxicity on non-target water bugs. Research in Veterinary Science 107: 95–101.

Govindarajan, M., M. Nicoletti & G. Benelli, 2016b. Bio-physical characterization of poly-dispersed silver nanocrystals fabricated using Carissa spinarum: a potent tool against mosquito vectors. Journal of Cluster Science 27: 745–761.

Gow, N. A. R. & G. W. Gooday, 1983. Ultrastructure of chitin in hyphae of Candida albicans and other dimorphic and mycelial fungi. Protoplasma 115: 52–58.

Huang, M., E. Khor & L. Y. Lim, 2004. Uptake and cytotoxicity of chitosan molecules and nanoparticles: effects of molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Pharmaceutical Research 21: 344–353.

Jaganathan, A., K. Murugan, C. Panneerselvam, P. Madhiyazhagan, D. Dinesh, C. Vadivalagan, A. T. Aziz, B. Chandramohan, U. Suresh, R. Rajaganesh, J. Subramaniam, M. Nicoletti, A. Higuchi, A. A. Alarfaj, M. A. Munusamy, S. Kumar & G. Benelli, 2016. Earthworm-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: a potent tool against hepatocellular carcinoma, pathogenic bacteria, Plasmodium parasites and malaria mosquitoes. Parasitology International 65: 276–284.

Julkapli, N.M., Z. Ahmad & H. M. Akil, 2009. X-ray diffraction studies of cross linked chitosan with different cross linking agents for waste water treatment application. In Saat, A., H. A. Kassim, M. H. H. Jumali, J. M. Saleh, M. R. Othman, A. Ibrahim, F. M. Idris & M. H. A.-R. M. Ahmad (eds) Neutron and X-Ray Scattering. Advancing Materials Research, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 106–111.

Kalimuthu, K., S. M. Lin, L. C. Tseng, K. Murugan & J. S. Hwang, 2014. Bio-efficacy potential of seaweed Gracilaria firma with copepod, Megacyclops formosanus for the control larvae of dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Hydrobiologia 741: 113–123.

Kaur, P., R. Thakur & A. Choudhary, 2012. An in-vitro study of antifungal activity of silver/chitosan nanoformulations against important seed borne pathogens. International Journal of Science & Technology Research 1: 83–86.

Kaviya, S., J. Santhanalakshmi, B. Viswanathan, J. Muthumary & K. Srinivasan, 2011. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Citrus sinensis peel extract and its antibacterial activity. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 79: 594–598.

Krishna Rao, K. S. V., P. Ramasubba Reddya, Y.-I. Lee & C. Kim, 2012. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan–PEG–Ag nanocomposites for antimicrobial application. Carbohydrate Polymers 87: 920–925.

Lamarque, G., J. M. Lucas, C. Viton & A. Domard, 2005. Physicochemical behavior of homogeneous series of acetylated chitosans in aqueous solution: role of various structural parameters. Biomacromolecules 6: 131–142.

Lee, D. S., C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins & D. E. McAllister, 1980. Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes. North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, Raleigh, NC.

Lertsutthiwong, P., N. C. How, S. Chandrkrachang & W. F. Stevens, 2002. Effect of chemical treatment on the characteristics of shrimp chitosan. Journal of Metals, Materials and Minerals 12: 11–18.

Madhiyazhagan, P., K. Murugan, A. N. Kumar, T. Nataraj, D. Dinesh, C. Panneerselvam, J. Subramaniam, P. Mahesh Kumar, U. Suresh, M. Roni, M. Nicoletti, A. A. Alarfaj, A. Higuchi, M. A. Munusamy & G. Benelli, 2015. Sargassum muticum-synthesized silver nanoparticles: an effective control tool against mosquito vectors and bacterial pathogens. Parasitology Research 114: 4305–4317.

Magudapathy, P., P. Gangopadhyay, B. Panigrahi, K. Nair & S. Dhara, 2001. Electrical transport studies of Ag nanoclusters embedded in glass matrix. Physica B: Condensed Matter 299(1–2): 142–146.

Mehlhorn, H., 2008. Encyclopedia of Parasitology, 3rd ed. Springer, Heidelberg.

Mohamed, E., I. Badawy & A. F. EL-Aswad, 2012. Insecticidal activity of chitosans of different molecular weights and chitosan–metal complexes against cotton leafworm Spodoptera littoralis and oleander aphid Aphis nerii. Plant Protection Science 48: 131–141.

Muhammed Rafeeq, P. E., V. Junise, R. Saraswathi, P. N. Krishnan & C. Dilip, 2010. Development and characterization of chitosan nanoparticles loaded with isoniazid for the treatment of tuberculosis. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Science 1: 383–390.

Murugadoss, A. & A. Chattopadhyay, 2008. A ‘green’ chitosansilver nanoparticle composite as a heterogeneous as well as micro-heterogeneous catalyst. Nanotechnology 19: 015603.

Murugan, K., R. Vahitha, I. Baruah & S. C. Das, 2003. Integration of botanical and microbial pesticides for the control of the filarial vector, Culex quinquefasciatus. Annals of Medical Entomology 12: 12–23.

Murugan, K., M. Aamina Labeeba, C. Panneerselvam, D. Dinesh, U. Suresh, J. Subramaniam, P. Madhiyazhagan, J.-S. Hwang, L. Wang, M. Nicoletti & G. Benelli, 2015a. Aristolochia indica green-synthesized silver nanoparticles: a sustainable control tool against the malaria vector Anopheles stephensi? Research Veterinary Science 102: 127–135.

Murugan, K., N. Aarthi, K. Kovendan, C. Panneerselvam, B. Chandramohan, P. M. Kumar, D. Amerasan, M. Paulpandi, R. Chandirasekar, D. Dinesh, U. Suresh, J. Subramaniam, A. Higuchi, A. A. Alarfaj, M. Nicoletti, H. Mehlhorn & G. Benelli, 2015b. Mosquitocidal and antiplasmodial activity of Senna occidentalis (Cassiae) and Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae) from Maruthamalai hills against Anopheles stephensi and Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitology Research 114: 3657–3664.

Murugan, K., G. Benelli, S. Ayyappan, D. Dinesh, C. Panneerselvam, M. Nicoletti, J.-S. Hwang, P. M. Kumar, J. Subramaniam & U. Suresh, 2015c. Toxicity of seaweed-synthesized silver nanoparticles against the filariasis vector Culex quinquefasciatus and its impact on predation efficiency of the cyclopoid crustacean Mesocyclops longisetus. Parasitology Research 14: 2243–2253.

Murugan, K., J. S. E. Venus, C. Panneerselvam, S. Bedini, B. Conti, M. Nicoletti, S. K. Sarkar, J.-S. Hwang, J. Subramaniam, P. Madhiyazhagan, P. M. Kumar, D. Dinesh, U. Suresh & G. Benelli, 2015d. Biosynthesis, mosquitocidal and antibacterial properties of Toddalia asiatica-synthesized silver nanoparticles: do they impact predation of guppy Poecilia reticulata against the filariasis mosquito Culex quinquefasciatus? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22: 17053–17064.

Murugan, K., A. Jaganathan, D. Dinesh, U. Suresh, R. Rajaganesh, B. Chandramohan, J. Subramaniam, M. Paulpandi, C. Vadivalagan, L. Wang, J. S. Hwang, H. Wei, M. Saleh Alsalhi, S. Devanesan, S. Kumar, K. Pugazhendy, A. Higuchi, M. Nicoletti & G. Benelli, 2016. Synthesis of nanoparticles using chitosan from crab shells: implications for control of malaria mosquito vectors and impact on non-target organisms in the aquatic environment. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 132: 318–328.

Muthukumaran, U., M. Govindarajan & M. Rajeswary, 2015. Mosquito larvicidal potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Chomelia asiatica (Rubiaceae) against Anopheles stephensi, Aedes aegypti, and Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitology Research 114: 989–999.

Muzzarelli, R. A. A. & R. Rochetti, 1985. Determination of the degree of deacetylation of chitosan by first derivative ultraviolet spectrophotometry. Journal of Carbohydrate Polymers 5: 461–472.

Page, L. M. & B. M. Burr, 1991. A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico. The Peterson Field Guide Series, vol. 42. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

Panneerselvam, C., K. Murugan, K. Kovendan, P. Mahesh Kumar & J. Subramaniam, 2013. Mosquito larvicidal and pupicidal activity of Euphorbia hirta Linn. (Family: Euphorbiaceae) and Bacillus sphaericus against Anopheles stephensi Liston (Diptera: Culicidae). Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 6: 102–109.

Patil, S. V., H. P. Borase, C. D. Patil & B. K. Salunke, 2012a. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using latex from few Euphorbian plants and their antimicrobial potential. Applied Biochemistry Biotechnology 167: 776–790.

Patil, C. D., H. P. Borase, S. V. Patil, R. B. Salunkhe & B. K. Salunke, 2012b. Larvicidal activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Pergularia daemia plant latex against Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi and nontarget fish Poecillia reticulate. Parasitology Research 111: 555–562.

Patil, C. D., S. V. Patil, H. P. Borase, B. K. Salunke & R. B. Salunkhe, 2012c. Larvicidal activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Plumeria rubra plant latex against Aedes aegypti and Anopheles stephensi. Parasitology Research 110: 1815–1822.

Prasanna Kumar, K., K. Murugan, K. Kovendan, J.-S. Hwang & D. R. Barnard, 2012. Combined effect of seaweed Sargassum wightii greville and Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis against coastal mosquito vector, Anopheles sundaicus (L.) Tamil Nadu. India. Science Asia 38: 141–146.

Rabea, E. I., M. E. I. Badawy, T. M. Rogge, C. V. Stevens & G. Smagghe, 2005. Insecticidal and fungicidal activity of new synthesized chitosan derivatives. Pest Management Science 61: 951–960.

Rai, M., A. Yadav & A. Gade, 2009. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnology Advances 27: 76–83.

Rao, J. V. & P. Kavitha, 2010. In vitro effects of chlorpyrifos on the acetylcholinesterase activity of euryhaline fish, Oreochromis mossambicus. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung C 65: 303–306.

Roy, K., C. K. Sarkar & C. K. Ghosh, 2015. Plant-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles using parsley (Petroselinum crispum) leaf extract: spectral analysis of the particles and antibacterial study. Applied Nanoscience 5: 945–951.

Ruparelia, J. P., A. K. Chatterjee, S. P. Duttagupta & S. Mukherji, 2008. Strain specificity in antimicrobial activity of silver and copper nanoparticles. Acta Biomaterialia 4: 707–716.

Sabbour, M. M., 2013. Entomotoxicity assay of nanoparticle 4-(silica gel Cab-O-Sil-750, silica gel Cab-O-Sil-500) against Sitophilus oryzae under laboratory and store conditions in Egypt. Science Research Report 1: 67–74.

Sahab, A. F., A. I. Waly, M. M. Sabbour & L. S. Nawar, 2015. Synthesis, antifungal and insecticidal potential of Chitosan (CS)-g-poly (acrylic acid) (PAA) nanoparticles against some seed borne fungi and insects of soybean. International Journal of Chem Tech Research 8: 589–598.

Sanpui, P., A. Murugadoss, P. V. Prasad, S. S. Ghosh & A. Chattopadhyay, 2008. The antibacterial properties of a novel chitosan–Ag–nanoparticle composite. International Journal of Food Microbiology 124: 142–146.

Saraswathy, G., S. Pal, C. Rose & T. P. Sastry, 2001. A novel bio-inorganic bone implant containing deglued bone, chitosan and gelatin. Bulletin of Materials Science 24: 415–420.

Sorlier, P., A. Denuziere, C. Viton & A. Domard, 2001. Relation between the degree of acetylation and the electrostatic properties of chitin and chitosan. Biomacromolecules 2: 765–772.

Souza, B. W. S., M. A. Cerqueira, J. T. Martins, A. Casariego, J. A. Teixeira & A. A. Vicente, 2010. Influence of electric fields on the structure of chitosan edible coatings. Food Hydrocolloids 24: 330–335.

Stuart, B. H., 2002. Polymer Analysis. Wiley, Chichester.

Subramaniam, J., K. Murugan, C. Panneerselvam, K. Kovendan, P. Madhiyazhagan, P. M. Kumar, D. Dinesh, B. Chandramohan, U. Suresh, M. Nicoletti, A. Higuchi, J. S. Hwang, S. Kumar, A. A. Alarfaj, M. A. Munusamy, R. H. Messing & G. Benelli, 2015. Eco-friendly control of malaria and arbovirus vectors using the mosquitofish Gambusia affinis and ultra-low dosages of Mimusops elengi-synthesized silver nanoparticles: towards an integrative approach? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22: 20067–20083.

Subramaniam, J., K. Murugan, C. Panneerselvam, K. Kovendan, P. Madhiyazhagan, D. Dinesh, P. Mahesh Kumar, B. Chandramohan, U. Suresh, R. Rajaganesh, M. Saleh Alsalhi, S. Devanesan, M. Nicoletti, A. Canale & G. Benelli, 2016. Multipurpose effectiveness of Couroupita guianensis-synthesized gold nanoparticles: high antiplasmodial potential, field efficacy against malaria vectors and synergy with Aplocheilus lineatus predators. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 23: 7543–7558.

Sukumar, K., M. J. Perich & L. R. Booba, 1991. Botanical derivatives in mosquito control: a review. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 7: 210–237.

Suman, T. Y., S. R. Radhika Rajasree, A. Kanchana & S. B. Elizabeth, 2013. Biosynthesis, characterization and cytotoxic effect of plant mediated silver nanoparticles using Morinda citrifolia root extract. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 106: 74–78.

Suresh, U., K. Murugan, G. Benelli, M. Nicoletti, D. R. Barnard, C. Panneerselvam, P. M. Kumar, J. Subramaniam, D. Dinesh & B. Chandramohan, 2015. Tackling the growing threat of dengue: Phyllanthus niruri-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their mosquitocidal properties against the dengue vector Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitology Research 114: 1551–1562.

Tan, X. L., S. Wang, X. Li & G. Zhang, 2010. Optimizing and application of micro-encapsulated artificial diet for Orius sauteri (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae). Acta Entomologica Sinica 53: 891–900.

Templeton, A. C., W. P. Wuelfing & R. W. Murray, 2000. Monolayer-protected cluster molecules. Accounts of Chemical Research 33: 27–36.

Tiwari, D. K. & J. Behari, 2009. Biocidal nature of treatment of Ag-nanoparticle and ultrasonic irradiation in Escherichia coli dh5. Advances in Biological Research 3: 89–95.

Trung, T. S., W. W. Thein-Han, N. T. Qui, C.-H. Ng & W. F. Stevens, 2006. Functional characteristics of shrimp chitosan and its membranes as affected by the degree of deacetylation. Bioresource Technology 97: 659–663.

Twu, Y. K., Y. W. Chen & C. M. Shih, 2008. Preparation of silver nanoparticles using chitosan suspensions. Powder Technology 185: 251–257.

Usha, C. & D. G. A. Rachel, 2014. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles by Acacia nilotica and their antibacterial activity. International Journal of Scientific Research 3: 27–29.

Walker, T., C. I. Jeffries, K. L. Mansfield & N. Johnson, 2014. Mosquito cell lines: history, isolation, availability and application to assess the threat of arboviral transmission in the United Kingdom. Parasites & Vectors 7: 1–9.

Ward, M. & G. Benelli, 2017. Avian and simian malaria: do they have a cancer connection? Parasitology Research. doi:10.1007/s00436-016-5352-3.

Wazed Ali, S., S. Rajendran & M. Joshi, 2001. Synthesis and characterization of chitosan and silver loaded chitosan nanoparticles for bioactive polyesters. Carbohydrate Polymers 83: 438–446.

Wei, D., W. Sun, W. Qian, Y. Ye & X. Ma, 2009. The synthesis of chitosan-based silver nanoparticles and their antibacterial activity. Carbohydrate Research 344: 2375–2382.

WHO, 2014. Malaria. Fact sheet No. 94.

Yang, K., N. S. Xu & W. W. Su, 2010. Co-immobilized enzymes in magnetic chitosan beads for improved hydrolysis of macromolecular substrates under a time-varying magnetic field. Journal of Biotechnology 148: 119–127.

Yoshizuka, K., Z. Lou & K. Inoue, 2000. Silver-complexed chitosan microparticles for pesticide removal. Reactive Functional Polymers 44: 47–54.

Zhang, M. I., T. Tan, H. Yuan & C. Rui, 2003. Insecticidal and fungicidal activities of chitosan and oligochitosan. Journal of Bioactive Compatible Polymers 18: 391–400.

Zhao, G. J. & S. E. Stevens, 1998. Multiple parameters for the comprehensive evaluation of the susceptibility of Escherichia coli to the silver ion. Biometals 11: 27–32.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the editor Veronica Ferreira and the two anonymous reviewers whose comments contributed to improve the manuscript. A. Jaganathan is grateful to the University Grant Commission (New Delhi, India), Project No. PDFSS-2014-15-SC-TAM-10125. The authors would like to thank the financial support rendered by King Saud University, through the Vice Deanship of Research Chairs. We are grateful for financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan through the Grant No. MOST 104-2611-M-019-004, MOST 105-2621-M-019-001 and MOST 105-2918-I-019-001 to J.-S. Hwang as well as the Grant No. MOST 104-2811-M-019-005 and MOST 105-2811-M-019-008 to L.-C. Tseng.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Handling editor: Verónica Jacinta Lopes Ferreira

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murugan, K., Anitha, J., Suresh, U. et al. Chitosan-fabricated Ag nanoparticles and larvivorous fishes: a novel route to control the coastal malaria vector Anopheles sundaicus?. Hydrobiologia 797, 335–350 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3196-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-017-3196-1