Abstract

Boyer–Moore (BM) algorithm is a single pattern string matching algorithm. It is considered as the most efficient string matching algorithm and used in many applications. The algorithm first calculates two string shift rules based on the given pattern string in the preprocessing phase. Using the two shift rules, pattern matching operations are performed against the target input string in the second phase. The string shift rules calculated in the first phase let parts of the target input string be skipped where there are no matches to be found in the second phase. The second phase is a time consuming process and needs to be parallelized in order to realize the high performance string matching. In this paper, we parallelize the BM algorithm on the latest many-core accelerators such as the Intel Xeon Phi and the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU along with the general-purpose multi-core microprocessors. For the parallel string matching, the target input data is partitioned amongst multiple threads. Data lying on the threads’ boundaries is searched redundantly so that the pattern string lying on the boundary between two neighboring threads cannot be missed. The redundant data search overheads increases significantly for a large number of threads. For a fixed target input length, the number of possible matches decreases as the pattern length increases. Furthermore, the positions of the pattern string are spread all over the target data randomly. This leads to the unbalanced workload distribution among threads. We employ the dynamic scheduling and the multithreading techniques to deal with the load balancing issue. We also use the algorithmic cascading technique to maximize the benefit of the multithreading and to reduce the overheads associated with the redundant data search between neighboring threads. Our parallel implementation leads to \(\sim \)17-times speedup on the Xeon Phi and \(\sim \)47-times speedup on the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU compared with a serial implementation on the host Intel Xeon processor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

String matching is an important algorithm commonly used in computer and network security, bioinformatics, among many other applications. Boyer–Moore (BM) algorithm [1] is a classic single-pattern string matching algorithm developed by Robert S. Boyer and J. Strother Moore. This algorithm is known to be one of the most efficient string matching algorithms. Given a sequence of characters (pattern), the BM searches for possible matches in the input string (or target). The algorithm first calculates the two string shift rules based on the given pattern in the preprocessing phase. Then the pattern matching is performed using the two shift rules against the target input data in the second phase. The shift rules calculated in the first phase help skip parts of the target input string in the second phase where there are no matches to be found. The second phase is a time consuming process and needs to be parallelized in order to realize the high performance string matching.

Recently, many-core accelerator chips such as the graphic processing units (GPUs) from Nvidia and AMD, Intel’s Many Integrated Core (MIC) architectures, among others are becoming increasing popular. The influence of these chips is rapidly growing in the high performance computing (HPC) server market and in the Top 500 list, in particular. They have a large number of cores and multiple threads per core, levels of cache hierarchies, large amounts (\(>\)5GB) of the on-board memory, and \(>\)1 Tflops peak performance for the double precision arithmetic per chip. They are mostly utilized as co-processors and execute parallel program kernels commanded by the host CPU with respect to the input data provided from the host memory to the on-board device memory. Using the many-core accelerators, a number of innovative performance improvements have been reported for the HPC applications and many more are still to come.

In this paper, we develop a high performance parallelization for the BM string matching algorithm on the many-core accelerator chips such as the Intel Xeon Phi and the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU. We partition the target input data amongst multiple threads for parallel execution of the BM algorithm. Data lying on the threads’ boundaries are searched redundantly so that the pattern string lying on the boundary between two neighboring threads can be found. The redundant data search overheads increases as the number of threads increases. The overhead is significant on the GPU, in particular, where a huge number of fine-grain threads are executed, because it increases the pressure on the on-chip shared memories. For a fixed target length, the number of possible match occurrences decreases as the pattern length increases. Furthermore, the positions of the pattern string are spread all over the target data randomly. This leads to irregular execution times among threads participating in the parallel execution, because the threads which find a smaller number of matches finish earlier than the threads with a larger number of matches. Our parallelization approach deals with the irregular workload distribution with a careful target data partitioning to generate appropriate number of data chunks. Also we use the dynamic scheduling and the multithreading to deal with the load balancing issue. The overheads associated with the redundant data search increases significantly as the pattern size increases and the number of threads increases. For example, on the GPU, the size of redundantly searched data is more than two times the size of the target when the pattern size is 50 and the number of threads reaches \(\sim \)178 million. This significantly overloads the shared memories of the GPU. We use the algorithmic cascading technique [5] to reduce the burden on the shared memories of the GPU. The algorithmic cascading also helps maximizing the benefit of the multithreading. Our parallel implementation leads to \(\sim \)17-times speedup on the Xeon Phi and \(\sim \)47-times speedup on the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU compared with a serial implementation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 explains the computational characteristics of the BM algorithm. Section 3 describes the architectures of the latest many-core accelerator chips including the Intel Xeon Phi and the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU. Section 4 explains our parallelization approach for optimizing the workload balancing among parallel threads and the algorithmic cascading technique to reduce the burden on the shared memory. Section 5 shows the experimental results on the general-purpose Intel multi-core processor, the Xeon Phi, and the Nvidia Tesla K20. Section 6 wraps up the paper with conclusions.

2 Boyer–Moore algorithm

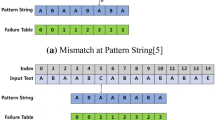

Boyer–Moore (BM) algorithm [1] is a single-pattern string matching algorithm developed by Robert S. Boyer and J. Strother Moore in 1977. Given a sequence of characters (pattern), the BM searches for the possible matches in the input string (or target). The BM algorithm consists of two phases: preprocessing phase and pattern matching phase. In the preprocessing step, two string shift rules are calculated in advance using the given pattern string. They are the bad character shift rule (calculated when there is no match) and the good suffix shift rule (calculated when there is a match). Using these shift rules, the pattern matching is attempted against the target in the second phase. The matching starts from the rightmost character of the pattern to the left. Whether there is a match or not, the position shift for the next match attempt is directed to the right.

2.1 Bad character shift

The pattern matching starts from the rightmost character of the pattern against the target. Whenever there is a mismatch found for a character in the middle of the pattern matching, we can skip a number of characters in the target string. The Bad Character Shift uses this matching rule. Assume that there is a pattern string “GCAGAGAG” with 8 characters as shown in Table 1 below. A pattern matching is attempted in Table 2 for a target string with 22 characters. We assume the following two cases:

-

Case 1: A pattern matching is attempted at pattern [7] (“G”) and target [7] (“C”). As they do not match, a “C” character is searched in the pattern string which is located at pattern [1]. Therefore, we skip 6 characters and locate the “C” character of the target at pattern [7].

Table 1 Pattern array Table 2 Target array and matching process -

Case 2: The next pattern matching is attempted starting from target [13] and pattern [7]. As they do not match and we cannot find the missing character “T” in the pattern, 8 characters (length of the pattern) are skipped and the pattern is located from target [14] to target [21].

As the result of the above, a bad character shift table is constructed as in Table 3. Figures 1 and 2 above illustrate the two cases for the Bad Character Shift.

2.2 Good suffix shift

The Good Suffix rule searches for either a matching suffix or a symmetric prefix–suffix pair in the pattern. After finding such strings, we can skip a number of characters accordingly. Assume that there is a pattern string “GCAGAGAG” with 8 characters. A suffix or a prefix–suffix pair is searched for the pattern as shown in Table 4:

-

For single character “G” located at pattern [0] and pattern [7], we find a common prefix–suffix pair (Good suffix (GS) case 2.

Table 4 Finding suffix or prefix–suffix pair -

For characters with lengths 2 or 3, there is no common suffix or prefix–suffix pair.

-

For characters with length 4, we find a common suffix “AG” (GS case 1).

-

For characters with length 5, there is no common suffix or prefix–suffix pair.

-

For characters with length 6, we find a common suffix “AGAG” (GS case 1).

-

For characters with length 7, there is no common suffix or prefix–suffix pair.

-

For characters with length 8, we find a common prefix–suffix pair “GCAGAGAG” (GS case 2).

According to the above, we construct a suffix array table (Table 5).

Figure 3 illustrates the GS case 1. Figure 4 illustrate the GS case 2 where there is a common prefix–suffix pair. In this case, we skip the characters so that the prefix is located under the target with which the previous suffix was matched.

Table 6 shows the matching process for a pattern “GCAGAGAG” against the target string. As explained above, the pattern matching is first attempted at the last character of the pattern (pattern [7]) and target [7]. The pattern [4:7] and target [4:7] match and the first mismatch occurs at target [3]. Referring to the Suffix_Array [3] in Table 5, we find that there is a common suffix with length 2. Therefore we shift 4 characters to locate pattern [2:3] under target [6:7].

2.3 Time complexity of the BM algorithm

The time complexity for the BM algorithm is O(3 m) when there is no match found in the target and O(mn) when at least one match is found (m: length of pattern, n: length of target) [2]. According to the Galil Rule [4], the BM is superior to other string matching algorithms because of its linear time complexity. However, when there is (are) a match (matches) found, its complexity depends on the length of the target. Thus, when the length of the target increases, its execution time also increases accordingly.

3 Archictectures of many-core accelerator chips

Recently, many-core accelerator chips are becoming increasingly popular for the HPC applications. Representative chips are the Nvidia Tesla K20 based on the Kepler GK110 architecture and the Intel Xeon Phi based on the MIC architecture. In the following subsections, we describe these architectures.

3.1 Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU

The latest GPU architecture is characterized by a large number of uniform fine-grain programmable cores or thread processors which have replaced separate processing units for shader, vertex, and pixel in the earlier GPUs. Also, the clock rate of the latest GPU has ramped up significantly. These have drastically improved the floating-point performance of the GPUs, far exceeding that of the latest CPUs. The fine-grain cores (or thread processors) are distributed in multiple Streaming Multiprocessors (SM) (or Thread Blocks) (see Fig. 5). Multiple threads assigned to each SM execute in the SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) mode. Each thread executes the same instruction directed by the common Instruction Unit on its own data streaming from the device memory to the on-chip cache memories and registers. When a running group of threads (or WARP) encounters a cache miss, for example, the context is switched to a new thread group (or WARP) while the cache miss is serviced for the next few hundred cycles. Thus the GPU executes in a multithreaded fashion as well [10].

The GPU is built around a sophisticated memory hierarchy as shown in Fig. 5. There are registers and local memories belonging to each thread processor or core. The local memory is an area in the off-chip device memory. Shared memory, level-1 (L-1) cache, and read-only data cache are integrated in a thread block of the GPU. The shared memory is a fast (as fast as registers) programmer-managed memory. Level-2 (L-2) cache is integrated on the GPU chip and used amongst all the thread blocks. Global memory is an area in the off-chip device memory accessed from all the thread blocks, through which the GPU can communicate with the host CPU. Data in the global memory gets cached directly in the shared-memory by the programmer or they can be cached through the L-2 and L-1 caches automatically as they get accessed. There are constant memory and texture memory regions in the device memory also. Data in these regions is read-only. They can be cached in the L-2 cache and the read-only data cache.

In order to efficiently utilize the latest advanced GPU architectures, programming environments such as CUDA from Nvidia [9], OpenCL from Khronos Group [12], OpenACC [13] from a subgroup of OpenMP Architecture Review Board (ARB) have been developed. Using these environments, users can have a more direct control over the large number of GPU cores and its sophisticated memory hierarchy. The flexible architecture and the programming environments have led to a number of innovative performance improvements in many application areas and many more are still to come.

3.2 Intel Xeon Phi

The Intel Xeon Phi (codenamed Knights Corner) is based on the Intel MIC architecture which combines multiple \(\times \)86 cores on a single chip [6]. This chip can run in either the native mode where an application runs directly on it or in the offload mode where the application runs on the host side and only the selected regions (compute-intensive regions) are offloaded to the Xeon Phi. For the offload mode, the Xeon Phi is connected to a host Intel Xeon processor through a PCI-Express bus. In this paper, we use the Xeon Phi 5110P for our parallel implementation of the BM:

-

This coprocessor has 60 in-order compute cores supporting 64-bit x86 instructions. These cores are connected by a high performance bidirectional ring interconnect (see Fig. 6). It also has one service core, thus total 61 cores on the chip.

-

Each core is clocked at 1053MHz and offers the four-way simultaneous multi-threading (SMT), 512-bit wide SIMD vectors which correspond to eight double precision or sixteen single precision floating point numbers.

-

Each core has a 32KB L1 data cache, a 32 KB L1 instruction cache, and 512KB unified L2 cache. Thus, 60 cores have a combined 30 MB L2 cache. The L2 cache is fully coherent using the hardware support.

-

The Xeon Phi chip has 16 memory channels delivering up to 5GT/s. The total size of the on-board system memory is 8GB.

Programmers can use the same programming languages and models on the Xeon Phi as the Intel Xeon Processor. It can run applications written in Fortran, C/C++, etc., and parallel models such as OpenMP, MPI, Pthreads, Intel Clik Plus, Intel Thread Building Block [6].

4 High performance parallelization of Boyer–Moore algorithm

The BM algorithm consists of the preprocessing phase and the pattern matching phase as explained in Sect. 2. We parallelize the second phase of the BM where the two shift rules generated in the first phase are used for the pattern matching against the target input data loaded in the memory (see Fig. 7). Previously, there have been research on parallelizing the BM algorithm on the GPU [7], [11, 14]. In [11], they compared the performance of the BM algorithm, the Knuth-Morris-Pratt algorithm, and a brute-force approach. They proved that the BM is most efficient. In [7, 14], they conducted a study on parallelizing the Boyer–Moore-Horspool algorithm on a GPU for a bioinformatics application. All these previous research focused on maximizing the utilization of the GPU cores and its memory hierarchy. In this paper, we parallelize the BM in order to optimize the workload distribution, redundant data copy and search overheads, etc., on the many-core accelerator chips and multi-core processors.

4.1 Issues in parallelizing Boyer–Moore algorithm

The time complexity for the BM algorithm grows with the increase in the length of the target when there is (are) a match (matches). When there is no match, the complexity depends only on the length of the pattern. Therefore, when we parallelize the BM algorithm we need to minimize the execution time for the large target sizes. For the parallel execution of the BM, we partition the target data amongst a number of threads. Some threads would find matches whereas other threads may find no matches. Thus the workload distribution has large variances and we need to balance the workload amongst the threads participating in the parallel execution. Furthermore, when partitioning the target input data for the parallel execution, data lying on the threads’ boundaries are searched redundantly so that the pattern string lying on the boundary can be found. The overheads associated with the redundant data search increases significantly as the pattern size increases and the number of threads increases. Thus we need to reduce the overheads also.

4.2 Parallelization on multi-core processor and Xeon Phi

We first parallelize the BM algorithm on the Intel multi-core processor and on the Intel Xeon Phi which has a large number of \(\times \)86 cores. We parallelize the algorithm by partitioning the input target data into a number of chunks. Then we let each thread match the pattern with respect to its target data chunk. When we generate the target data chunks, we assume that we search (pattern_length\(-\)1)-bytes of data redundantly from its neighboring chunk. Although different threads have almost the same target length, they have different contents. The number of pattern occurrences in each thread may vary significantly. Thus the application of the two shift rules may result in different execution time for different threads. Figure 8 illustrates the parallel execution scenario where each thread is assigned a target chunk with almost the same length, however, some threads have finished its execution and sit idle while other threads are still working on the pattern matching. Thus the overall parallel execution time is determined by the laggard thread. In order to minimize the inefficiency of the idle threads, we partition the target data into smaller chunks and have each thread work on a number of chunks. We use the dynamic scheduling policy by letting a thread which finishes early for its assigned chunk pick up another chunk, thereby reduces the workload variances among threads. Figure 9 shows the execution scenario of the dynamic scheduling.

We also parallelize the BM algorithm on the Intel Xeon Phi. Basically we use the same parallelization methodology as we use for the multi-core microprocessor. However, we use the off-load mode of the Xeon Phi [6] so that the parallel kernel can be offloaded from the host multi-core processor to the Xeon Phi. The target data is first copied from the host memory to the on-board device memory of the Xeon Phi. Then the host CPU commands the execution of the parallel kernel on the Xeon Phi. Afterwards, the execution result is copied back to the host memory (Fig. 10). There are up to 60 cores for the user process on the Xeon Phi (plus one service core). Each core can have up to 4-way hyper-threading [8]. Therefore, we use up to 240 threads and the dynamic scheduling on the Xeon Phi. The overheads with the redundant data search is rather small on the Xeon Phi compared with the GPU as the maximum number of threads applicable is small (240).

C. Parallelization on GPU

In order to parallelize the BM on the GPU, we copy the target input data from the host memory and store in the Global Memory (GM) region of the device memory of the GPU board. Then the input target data stored in the GM is partitioned and loaded into the Shared Memory (SM) of a hardware block (or Streaming Multiprocessor: SMX) for the parallel execution. Threads in each SMX search the pattern in their assigned target data chunk in parallel. As in the multi-core and the Xeon Phi parallelization, we search (pattern_length\(-\)1)-bytes of data from its neighboring chunk redundantly because a pattern may lie on the boundaries of consecutive target data chunks. Since the SM is only accessible from the threads running on the same SMX, we redundantly copy the boundary data accessed by the different threads running on the different SMX. Figure 11 illustrates the parallel pattern matching performed by threads in each SMX for the data copied from the GM to the SM.

In our parallelization, we divide the data mapped to each SMX by the size of the shared memory (SM) to generate a number of software blocks. Thus each SMX handles multiple software blocks. This helps hide the GM access latencies by the multithreaded execution of the SMX. Furthermore, the high degree of multithreading on the GPU helps smoothen the irregular execution times on different threads. When the number of blocks mapped to each SMX increases beyond the capacity of the SMX (and the shared memory in each SMX), however, there will be blocks which do not get mapped to the SMX. This will saturate the SMX and also will leave many blocks idle. Furthermore it results in the increased mapping overheads.

In order to solve the problem of excessively high degree of multithreading, we cascade multiple blocks algorithmically (or algorithmic cascading: ACC) [5]. This increases the size of the block and the amount of work for each thread, and decreases the number of blocks mapped to each SMX. Figure 12 shows the parallel execution using the ACC technique. Unlike in the execution of Fig. 11 where each block is executed by each thread, every other block gets cascaded, for example, and executed by the same thread. Thus it increases the size of target data per thread and decrease the number blocks. This reduces the number of idle blocks which are not mapped, thus improve the benefit of multithreading. It also reduces the mapping overheads and leads to the improved performance.

The ACC also reduces the overheds associated with the redundant data search. The size of the redundantly searched data grows significantly with the size of the pattern and the number of threads. For example, the size of redundantly searched data is \(\sim \)2.08-times the size of the target when the pattern length is 50 and the number of threads (no_of_blocks \(\times \) no_of_threads/block) reaches \(\sim \)178 million. Using the ACC, the effective size of the target data per thread gets increased by the degree of the ACC. Thus, the data search overhead is also reduced.

5 Experimental results

In this section, we show the experimental results of parallelizing the BM algorithm on the multi-core processors, the Intel Xeon Phi, and the GPU. Table 7 summarizes the experimental environments. The multi-core processors are 2 Intel Xeon E5-2620 (2.0 GHz, 6 cores each), the host memory is 32GB in size, the Xeon Phi has 60 compute cores with 8GB of the on-board memory, the GPU is Nvidia Tesla K20 with 2496 single-precision cores and 5GB of the device memory. We used the CentOS 6.3. For the parallel implementation on the multi-core and the Xeon Phi, we used OpenMP [3]. For the parallel implementation on the GPU, we used CUDA [9, 10].

5.1 Results on multi-Core processors and Xeon Phi

Figure 13 shows the throughput performance (in Gbps) of the serial implementation and two parallel implementations with the static scheduling and the dynamic scheduling using 12 threads running on 12 cores (2 \(\times \) 6 cores). In all the experiments, we used 1000 chunks. Figure 14 shows the speedups of the two parallel implementations over the serial implementation. Overall the dynamic scheduling gives 11-times speedup over the serial implementation using 12 cores. The static scheduling gives 10-times speedup. The dynamic scheduling gives \(\sim \)10 % gain over the static scheduling. It helps balance the workloads among multiple threads.

The performance improvements get reduced as the length of the pattern increases. This is because we search (pattern_length\(-\)1)-bytes of redundant data from its neighboring chunks. As the pattern length increases, the size of the data chunk assigned to each thread increases which results in the enlarged problem size. For instance, when the number of target data chunks is 1000, 3996 characters are searched redundantly when the pattern size is 5. When the pattern size increases to 50 characters, 48,951 characters are searched redundantly.

Figure 15 shows the throughput performance (in Gbps) on the Xeon Phi using serial implementation and parallel implementations using 60, 120, 180, 240 threads. The best performance was obtained using 180 threads on 60 cores, thus 3-way hyper-threading was used in each core. The resulting throughput is greater than 80 Gbps and the average speedup is 14.75 and the maximum speedup is 17.14 over the serial implementation (Fig. 16).

5.2 Results on GPU

Figure 17 shows the throughput performance (in Gbps) on the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU compared with the serial implementation. The GPU experiments were conducted with and without using the ACC technique. Using the ACC, we obtained an average speedup of 33 and the maximum speedup of 47. The ACC gives 30 % better performance than without using it. As explained earlier in subsection A, the redundant data search and copy affects the performance. The amount of redundant data search using the ACC is significantly reduced to degree_of_ACC \(\times \) no_of_blocks \(\times \) (no_of_threads/block\(-\)1)\(\times \) (pattern_length\(-\)1). (For example, when the degree of ACC = 64, pattern length = 50, the no of blocks = 21,730, and the no of threads per block = 128, total 8,654,450,560 characters are searched redundantly.) The amount of the redundant data copy is calculated as (no_of_blocks\(-\)1)\(\times \) (pattern_length\(-\)1).

In order to search for an optimal degree of the ACC, we’ve conducted experiments by doubling it from 1 (no ACC) to 64. The Fig. 19 shows that, as the degree of the ACC increases, the performance steadily improves for all the pattern lengths. The ACC degree of 64 gives the best performance. Figure 20 shows the benefit of the ACC in the speedups.

For all the experimental results shown above, we’ve set the number of software blocks to be mapped to each SMX as 16 and the number of threads per each block as 128. These numbers denote the degree of the multithreading at the software block level and at the thread level within each block on our target Tesla K20 chip. In order to optimize the performance of the BM algorithm, we’ve searched these numbers through extensive experiments. The maximum number of software blocks that can be mapped to each SMX on the K20 is 16. The maximum number of threads that can be mapped to each SMX is limited to 2,048. Therefore we attempt to assign 16 blocks and let each block use 3KB of the shared memory when we set the size of the shared memory as 48KB (48KB/16 = 3KB). Then we set the number of threads to be mapped to each SMX as 128, because 2,048/16 = 128. Thus 3KB/128 = 24byte of the shared memory is assigned to each thread. In the same way, we’ve also set (no of software blocks per each SMX, no of threads per each block)-pairs as (8, 256), (4, 512), (2, 1024) as the Table 8 shows. The number of software blocks decreases to 8, 4, 2, thus the size of the shared memory mapped to each block increases to 6KB, 12KB, 24KB. The number of threads per each blocks, on the other hand, increases to 256, 512, 1024. Thus the size of the shared memory assigned to each thread remains at 24 bytes.

Figures 21 and 22 show the performance results of using the pair combinations shown in Table 8, when the degree of the ACC is set to 1 (no ACC). Mapping 16 blocks to each SMX and mapping 128 threads per each block give the best performance. Thus we’ve used these numbers in the experiments of which the results are shown in the above figures (Figs. 17, 18, 19, 20).

5.3 Summary of experimental results

Figures 23 and 24 show performance comparisons of the serial implementation, the parallel implementations on two 6-core Intel Xeon using 12 threads with the dynamic scheduling for the load balancing, implementations on the Intel Xeon Phi using 60 cores and 3-way hyper-threading per core, and on the Tesla K20 GPU using the ACC technique. Figure 23 shows the throughput comparisons and Fig. 24 shows the speedup comparisons among different parallel implementations over the serial implementation. Overall, the GPU implementation shows the best performance, followed by the Xeon Phi, then the multi-core implementation when comparing at the single chip level, because the multi-core performance is obtained using 2 chips. As the length of the pattern increases, the absolute performance (throughput) increases. However, the speedup decreases due to the computations performed on the redundantly searched data on the data chunk boundaries. Also, as the pattern length increases and the number of threads increases, the number of threads without any pattern match occurrences increases. This leads to unbalanced load distributions among the threads.

Throughput comparisons among the (no of blocksper SMX, no of threads per each block) pairs shown in Table 8

Speedup comparisons among the (no of blocksper SMX, no of threads per each block) pairs shown in Table 8

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we proposed a high performance parallelization of the BM algorithm which significantly improves the load balancing among parallel threads for the irregular workload distributions and the redundant data copy and search overheads on the many-core accelerator chips including the Intel Xeon Phi and the Nvidia GPU. Our parallelization approach partitions the given set of target input data to generate a number of data chunks. In order to optimize the load balancing among threads, we carefully decide the chunk size and the resulting number of chunks. Then we employ the dynamic scheduling to smoothen the execution time variances among different threads. On the Xeon Phi, the multithreading using the Hyper-Threading technology is also used to further the performance improvements. The multithreading on the GPU also improves the load balancing among threads by assigning a large number of threads per each core, thus the overall run time variance gets minimized. Furthermore, the GPU implementation uses the algorithmic cascading (ACC) to maximize the benefit of the multithreading and to minimize the redundant data copy and search overheads. Experimental results show \(\sim \)17-times speedup on the Xeon Phi and \(\sim \)47-times speedup on the Nvidia Tesla K20 GPU compared with a serial implementation.

References

Boyer, R.S., Moore, J.S.: A fast string searching algorithm. Commun. ACM 20(10), 762–772 (1977)

Cole, Richard: Tight bounds on the complexity of the Boyer–Moore string matching algorithm. SIAM J. Comput. 23(5), 1075–1091 (1994)

Dagum, Leonardo, Menon, Ramesh: OpenMP: an industry standard API for shared memory programming. Comput. Sci. Eng. IEEE 5(1), 46–55 (1998)

Galil, Zvi: On improving the worst case running time of the Boyer–Moore string matching algorithm. Commun. ACM 22(9), 505–508 (1979)

Harris, Mark: Optimizing parallel reduction in CUDA. NVIDIA Dev. Technol. 2, 45 (2007)

Jeffers, J., Reinders, J.: Intel Xeon Phi Coprocessor High Performance Programming, Newnes. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2013)

Kouzinopoulos, Charalampos S., Konstantinos G., Margaritis. String matching on a multicore GPU using CUDA informatics, 2009. PCI’09. 13th Panhellenic conference on IEEE 2009

Marr, D.T., et al.: Hyper-threading technology architecture and microarchitecture. Intel Technol. J. 6(1), 11 (2002)

NVIDIA.: CUDA Best Practices Guide: NVIDIA CUDA C Programming Best Practices Guide CUDA Toolkit 5.0, Oct. 2012

NVIDIA.: NVIDIA’s next generation CUDA compute architecture: Kepler GK110 white paper. http://www.nvidia.com/contents/PDF/kepler/NVIDIA-Kepler-GK110-Architecture-Whitepaper.pdf (2011). Accessed Nov 2011

Rao, C.S., Raju, K.B., Raju, V.S.: Parallel string matching with multi core processors-A comparative study for gene sequences. Glob. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 13(1), 25–41 (2013)

Stone, John E., Gohara, David, Shi, Guochun: OpenCL: a parallel programming standard for heterogeneous computing systems. Comput. Sci. Eng. 12(3), 66 (2010)

The OpenACC application programming interface version 1.0. http://www.openacc.org/sites/default/files/OpenACC.1.0_0.pdf (2011). Accessed Nov 2011

Zhou, J., et al.: Implementation of string match algorithm BMH on GPU using CUDA. Energy Procedia 13, 1853–1861 (2011)

Acknowledgments

This research has been performed as a subproject (P14008) of project “National Supercomputing Technology Development and Research” and supported by the Korean Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI). This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (Grant No: 2012R1A1A2042267).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, Y., Lee, M., Nam, D. et al. High performance parallelization of Boyer–Moore algorithm on many-core accelerators. Cluster Comput 18, 1087–1098 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-015-0466-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-015-0466-4