Abstract

The Family Inventory of Resources and Stressors (FIRST) has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties in the assessment of families of children with emotional and behavior disorders (EBD). However, the extent to which ethnic/racial and developmental differences moderate the psychometric properties of this instrument is unknown. The study sample consisted of 150 families with an EBD child consecutively admitted to the Astor Transitions Program. This study seeks (1) to conduct a psychometric analysis of the FIRST subscales among African American and Hispanic/Latino families with older students versus early childhood students with EBD, and (2) to determine whether profiles will show greater stress for families of older students due to longer exposure to their EBD. Alpha coefficients were computed with a cutoff of 0.70 (or higher) indicating acceptable internal consistency reliability. Criterion variables reflecting family environment, mental health, and level of service correlated with relevant FIRST subscales assessed validity. Ethnic/racial and developmental effects were found to moderate the psychometric properties of the FIRST. No statistically significant between-group mean differences on the FIRST were found for families of early childhood versus older EBD students. Despite evidence of response bias on the part of families and lack of standardization during test administration by caseworkers, the current findings still reveal adequate reliability and limited validity of FIRST subscales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emotional and behavior disorders (EBD) are mental health conditions in children classified by a combination of DSM diagnoses and some measure of impairment or global functioning (Brauner & Stephens, 2006). Brauner and Stephens (2006) found in their review the literature that the prevalence of EBD ranged from 5 to 26%. Variability in the estimates of EBD can be attributed largely to the lack of a standard definition across governmental agencies and service programs. EBD reduce the chances of effective psychosocial and academic functioning among children later in life without appropriate mental health and educational services (Burns, 1996; Raver & Knitzer, 2002). However, there are barriers to addressing the unmet need for clinical and educational services for EBD students.

Underutilization of mental health services by families of EBD children are due partly to (1) lack of awareness of etiology in early childhood (2–7 years of age) and (2) a failure to consider the significant role of family and social environment. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers are devoting increasing attention to EBD during the early childhood period (Basten et al., 2016; Brauner & Stephens, 2006; Egger & Angold, 2006; Hallam, Lyons, Pretti-Frontczak, & Grisham-Brown, 2014; Raver & Knitzer, 2002). An evidence base is being created to substantiate some of the assumptions and clinical impressions about the nature of EBD. For example, the assertion that untreated EBD in early childhood leads to poorer psychosocial functioning in later years has received empirical support. In a Swedish study, Agnafors et al. (2016) demonstrated the longitudinal effects of risk and resilient factors during early childhood on emotional and behavioral problems at age 12.

The influence of family and social environment on EBD children is also being examined. Agnafors et al. (2016) combined maternal characteristics (e.g., education, occupation, and depression) and social environment (e.g., family structure and living conditions) into a measure of cumulative early life adversity for the child participants. There was a significant interaction effect in the final step of a regression analysis between the measure of cumulative early life adversity and early childhood temperament in predicting child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems at preadolescence (Agnafors et al., 2016). There was also evidence that genetic factors play a significant role in the outcomes which supported the researchers’ use of a biopsychosocial model.

Using data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods, Xue et al. (2005) also tested the effects of family/maternal factors and neighborhood disadvantage on mental health problems of depression, anxiety, withdrawal, and somatic complaints in a sample of 2805 children by cohorts of 3, 6, and 9 year olds over a 2 year period. Maternal depression and unemployment were significant positive predictors of poor mental health in children: neighborhood concentrated disadvantaged, comprised of the poverty rate, percentage of public assistance recipients, percentage of female-headed households, unemployment ratio, and percentage of Black residents, also significantly predicted high scores on their summary measure of internalizing disorders (Xue et al., 2005). This study, as well as the one by Agnafors et al. (2016), underscores the importance of assessing the impact of family and environmental challenges on EBD in children.

These studies also demonstrated that factors which promote resilience—i.e., family and community strengths, are also important as determinants of the course of EBD in children. Agnafors et al. (2016) found a maternal sense of coherence, a measure of coping ability, was negatively associated with a developmental trajectory toward internalizing or externalizing disorders in a birth cohort of Swedish children. Viewing the converse of family and community risk, Xue et al. (2005) found employment and post-secondary education among mothers, as well as family income, to be protective against the development of mental health problems in children living in Chicago neighborhoods. Xue et al. (2005) also found an index of the extent of participation in various neighborhood organizations by residents was a negative predictor of child mental health problems.

These findings provide empirical support for researchers who advocate the inclusion of child and family strengths in the assessment of needs for child mental health services (Cassidy, Lawrence, Vierbuchen, & Konold, 2013; Corliss, Lawrence, & Nelson, 2008; Epstein, 1999). Epstein (1999) pointed out that the strength-based approach is often included in the practice of social workers, psychologists, and counselors. Moreover, screening for strengths may facilitate the empowerment perspective inherent in the professional philosophies of social work, public health, and community psychology with regard to service provision for children and families in disadvantaged social environments. The empowerment perspective and strength-based approaches are variations on the common theme of identifying family and community resources which promote resiliency and reduce risks for EBD children in disadvantaged social environments.

Brauner and Stephens (2006) recommended the use of self-administered questionnaires with families of SED children. Specifically, they asserted.

The first step toward ensuring that children receive the mental health services they need…is to perform more research that is generalizable to them and sensitive to diverse cultural groups. This goes hand in hand with establishing the use of valid and reliable screening measures for emotional/behavioral disorders… The focus of future studies should be areas of high child poverty rates, children exposed to stressful life experiences, aid to single parents with dependent children, and social support and coping mechanisms. (Brauner & Stephens, 2006, pp. 306–307)

The above statements indicate the need for an instrument to address the family and community context in which EBD students function. Brauner and Stephens (2006) also insisted the selected scale be reliable and valid, as well as appropriate for preschool children of various cultural backgrounds.

These requirements have been reiterated by other early childhood researchers. Darling-Churchill and Lippman (2016), and Halle and Darling-Churchill (2016) claimed that measures to assess the social and emotional functioning of young children are needed that have adequate psychometric properties; are suitable for various ethnic/racial groups; and span the range from the early years to later childhood. These authors also acknowledged that observations of parents are essential for a holistic view of young children’s development (Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016). This information is also helpful because of young children’s cognitive-development limitation in reporting complex emotional problems (see Muris et al., 2010; Whaley, 1990). Thus the standard expectation of psychometric soundness and additional criteria of cultural and developmental applicability will generate useful data to plan mental health services for families in high-risk environments. Such challenges are further compounded in the assessment of service needs of young children with EBD.

The Family Inventory of Resources and Stressors (FIRST) has been shown to have adequate psychometric properties in the assessment of families with EBD children (Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). The FIRST is an assessment tool designed to allow service providers to rapidly and efficiently identify family resources and target areas of needs, facilitating the development of treatment plans that address self-reported stressors while capitalizing on family strengths and resources (Cassidy et al., 2013). “A practitioner’s focus on families’ or parents’ weaknesses, without acknowledging both their normative stress levels and strengths, may subtly communicate that they are incompetent caregivers” (Corliss et al., 2008, pp. 272–273). Families with multiple problems living in impoverished communities are the focus of assessments with the FIRST. Consistent with the empowerment perspective, according to Cassidy et al. (2013), the FIRST emphasizes the “family’s voice” in the assessment process by allowing families to identify their own resources and stressors.

Psychometric evaluations of the FIRST have yielded favorable evidence in terms of reliability and validity (Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). Unfortunately, the extent to which ethnic/racial and developmental differences moderate the psychometric properties of this instrument is unknown. Thus the purpose of this study is to determine whether ethnicity/race and developmental status play a role in its level of reliability and validity. Specifically, this study seeks to conduct a psychometric analysis of the FIRST by ethnicity/race and developmental status. It is hypothesized that the FIRST is a reliable and valid instrument for use with EBD students regardless of developmental status. Based on the view espoused by Burns (1996), another hypothesis is that the family profiles will show greater stress for parents of older students due to longer exposure to their EBD.

Method

Participants

The study sample consisted of 150 consecutive admissions to a transitions program between April 2010 and March 2013. The transition program serves children with emotional and behavior disorders transitioning from day treatment to different educational enironments where educational and mental health services often ate less integrated. The program provides casework support and follow-up to the child clients and their families during the transition. There were 82 (54%) Hispanic/Latino, 55 (38%) African American, and 13 (8%) Other ethnic/racial families served. Fifty-five (33%) EBD students were in preschool to second grade and were classified as early childhood students, and 95 (56%) were classified as older students being over age 7 and referred by day treatment programs. The gender breakdown of the client sample is 110 (73%) males and 40 (27%) females. The majority of the families were single-parent (37%), followed by foster care/adoptive (25%), two-parent families (14%), and extended families or other (5%). The family structure for 29 (19%) families was missing. The remaining 10 (11%) participants had missing data for developmental status. The “other” ethnic/racial group was not included in subsequent analyses due to the small sample size. That group had less than five cases per category in several analyses. The final sample used in subsequent analyses without missing data totaled N = 137.

Family Inventory of Resources and Stressors (FIRST)

The FIRST (Lawrence, 2005) is used to assess the strengths and needs of participating families. The FIRST contains 104 items identifying the families’ risk and resilience profiles, especially those from “multiproblem, low-income backgrounds” (Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). The resource section on the FIRST consists of 70 items divided into seven scales (some with subscales): basic life (subscales of living situation, financial situation, and physical health); personal (subscales of emotional and problem-solving); parent–child (subscales of authority and closeness); social support; partner relationship (subscales of satisfaction and negotiation); child education; and adult employment.

The Stressor section on the FIRST contains 34 items divided into two scales: emotional (subscales of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, sexual safety, and physical safety); and family/community (subscales of family and community).The items in both sections are scored on a scale to 1 “Almost never true” to 4 “Almost always true”. The items of summed up by subscales with higher scores indicating greater relevance of the subscale. There are 19 subscales. The FIRST subscales with their means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1. The FIRST was administered in interview-format to a single parent or caretaker as a family spokesperson. FIRST administration was part of the routine intake assessment by caseworkers in the transition program. All interviewers were limited to use of the English version of the FIRST, because it not translated into any other language: Informed consent was obtained before the assessment process was initiated. Corliss et al. (2008) reported the stressors and resources of families served by the same agency used in this study.

Criterion Variables

The following criteria will be evaluated in the validity assessments: external family environment, mental health and well-being, and level of service. Each family’s zip code was entered on the website http://www.city-data.com and 2011 estimated income, 2011 poverty level, 2004 salary/wage, and 2004 adjusted gross income (AGI) were taken for the corresponding neighborhoods. As a part of the intake assessments, participating families were asked “yes/no” questions about family history of mental illness and family history of substance abuse: A third variable was created by combining the two previous variables to add a category including both conditions for a history of dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance abuse. Each participating family was assigned to a level of care. They were automatically assigned by the program director (JW) to one contact per month upon entering the transition program. Levels of service were subsequently adjusted based on a better understanding of family needs. The levels of service were scored “Twice a month” (1), “Once a month” (2), “Bimonthly” (3), or “Quarterly” (4). The variable was recoded from 1 to 4 with higher scores reflecting more frequent contact or higher levels of service.

Statistical Analyses

Mean scores on FIRST subscales were compared via 2 (ethnicity/race) × 2 (developmental status) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Two sets of analyses estimated internal consistency reliability of FIRST subscales by ethnicity/race and developmental status. Alpha coefficients were computed for each subscale of the FIRST (see Cronbach, 1951). Peterson (1994) demonstrated in a meta-analysis that most alpha values fall between 0.70 and 0.82, so an alpha coefficient of 0.70 (or higher) is used as the cutoff for acceptable internal consistency reliability. Repeated-measures MANOVA will be performed on alpha coefficients across the 19 FIRST scales with the four groups defined by ethnicity/race and developmental status as levels of the independent variable. A frequency count of subscales with alphas greater than or equal to 0.70 will be conducted by ethnicity/race and developmental status. A 2 (ethnicity/race) × 2( developmental status) chi square test will be conducted on the percentages corresponding to these frequency counts. Criterion validity will be assessed by correlations among criterion variables reflecting family environment, mental health and well-being, and level of service and related FIRST subscales. Statistical significance is set at Type I error for two-tailed test of p < .05 for all analyses.

Results

Between-Group Mean Differences

Mean substitution was conducted at the item level before creating subscale scores. Means and standard deviations on the FIRST subscales by ethnicity/race and developmental status are presented in Table 1. The MANOVA with scores of the 19 subscales of the FIRST as the dependent variables revealed no statistically significant main effects for ethnicity/race, Wilk’s Λ = 0.91, F (19, 117) = 0.61, p = .89 and developmental status, Wilk’s Λ = 0.86, F (19, 117) = 1.03, p = .43; nor their interaction, Wilk’s Λ = 0.84, F (19, 117) = 1.21, p = .26.

Reliability

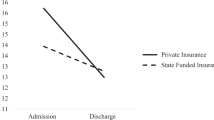

Internal consistency reliability was calculated by ethnicity/race and developmental status and for the total sample. The alpha coefficients from these analyses are presented in Table 2. Satisfactory reliability was established by examining the mean scores across FIRST subscales and by counting the number of scales with a coefficient alpha of 0.70 or higher. Repeated-measures MANOVA with the four groups defining the dependent variables for family group, a single independent variable yielded a statistically significant multivariate effect, Wilk’s Λ = 0.59, F (3, 16) = 3.79, p = .03, partial η = 0.42. Tests of within subjects effects revealed a statistically significant difference among the four groups, F (3, 54) = 3.20, p = .03, partial η = 0.15. Mean alpha coefficients by ethnicity/race and developmental status are presented in Fig. 1. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the subgroup of African American parents and Hispanic/Latino parents both with early childhood EBD students had average alpha coefficients above 0.82 and below 0.70, respectively. More details about this analysis are presented in the “Appendix”.

Interestingly, the difference between the mean alphas from pairwise comparisons of these two groups was not statistically significant (p = .22); and the lack of statistically significant mean differences was evident for comparisons of Hispanic/Latino families of early childhood EBD students to African American parents (p = 1.00) and Hispanic/Latino parents (p = 1.00) of older students with EBD (see Table 5 in Appendix). The statistical nonsignificance may be attributable to the fact that the standard error for the mean alpha coefficients of Hispanic/Latino families with young EBD students is twice as large as the remaining groups (see Table 4 in Appendix). Pairwise comparisons revealed that African American parents of young EBD children had, on average, subscale alphas that were statistically significantly different from the African American parents (p = .05) and Hispanic/Latino parents (p = .04) of older EBD student.

The 2 (ethnicity/race) × 2 (developmental status) chi square test revealed a statistically significant effect on frequency counts of the cutoff at alpha = 0.70, χ = 5.89, df = 1, p = .02, w = 2.01. For African American families with EBD children, 94.7% of the early childhood students and 73.7% of older students had FIRST subscales with internal consistency reliability coefficients of 0.70 or higher. In contrast, Hispanic/Latino families had FIRST subscales with alpha coefficients equal to or above a value of 0.70 in 63.2% of early childhood and 63.2% of the older EBD students. Less than one out of six (16.3%) FIRST subscales of the African American subsample, compared to more than one out of three (36.8%) for their Hispanic/Latino counterparts, showed unsatisfactory internal consistency reliability.

Validity

The FIRST subscales of living situation, financial situation, and community were statistically correlated with neighborhood level income variables. The living situation subscale was statistically significantly correlated with 2011 estimated income, r (88) = .22, p = .04; 2011 poverty level, r (88) = −.26, p = .02; 2004 salary/wage, r (88) = .26, p = .02; and 2004 AGI, r (88) = .28, p = .01. The subscales of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse were correlated with family reports of a history of mental illness, substance abuse and dual diagnosis. Reports of a family history of mental illness were statistically significantly correlated with the Substance Abuse subscale of the FIRST, r (76) = −.25, p = 03. All FIRST subscales were correlated with level of service. Level of service was statistically significantly correlated with the subscales of parent–child (authority), r (83) = −.24, p = .03; parent–child (closeness), r (83) = −.24, p = .03; and child education, r (82) = −.30, p = .01. Greater parental authority and closeness and more investment in child education were associated with lower levels of service. Level of service was not significantly correlated with the remaining FIRST scales, which is evidence of discriminant validity. These three significant scales have in common the fact that they are child-focused. In particular, these scales assess the the child client’s functioning in school and the family’s management of him or her. Thus the FIRST showed limited evidence of validity for this sample of families with EBD children.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to assess the reliability and validity of the FIRST and the moderating effects of ethnicity/race and developmental status. With regard to this goal, it was hypothesized that the FIRST is a reliable and valid instrument for use with EBD students. The reliability and validity assessments of the FIRST yielded satisfactory alpha coefficients and limited evidence of validity. Despite the fact that internal consistency reliability was adequate for the entire sample, there were moderating effects of ethnicity/race and developmental status. Specifically, the instrument was least reliable for Hispanic/Latino families of students with EBD. A substantial percentage of this ethnic/racial group had alpha coefficients below the cutoff of 0.70. In fact, the overall average alpha across the FIRST subscales yielded an unsatisfactory value for Hispanic/Latino families of early childhood EBD students.

Such findings emphasize the importance of considering cultural and linguistic diversity in the assessment of young children from Hispanic/Latino families. Both Darling-Churchill and Lippman (2016) and Halle and Darling-Churchill (2016) advocate the development of instruments for the assessment of young children in languages other than English. Cultural competence in the assessment and treatment of families with EBD children is considered an essential element of mental health services (Brauner & Stephens, 2006). We believe that the present findings from FIRST assessments of Hispanic/Latino parents of young EBD students are consistent with this argument. Indeed Xue et al. (2005) suggested that Hispanic/Latino ethnicity was associated with an increased risk of EBD in children. Cultural and linguistic barriers may discourage help-seeking among this group.

However, it would be premature to attribute the current findings to cultural and linguistic limitations of particular FIRST subscales. There were also some subscales that had smaller alpha coefficients for African American families. Future research is needed to understand the common and unique sources of poor reliability across ethnic/racial groups. Focus groups or qualitative research on FIRST administration with families of EBD students would be helpful in identifying such barriers. Another approach recommended by Cassidy et al. (2013) is to compare responses of parents and service providers in the FIRST assessment of families with EBD children. Corliss et al. (2008) included a measure to determine the utility and acceptability of the FIRST to clinical, at-risk, and nonclinical families. This methodology could be adapted to evaluate families’ attitudes toward the FIRST as a treatment planning tool and to identify cultural barriers.

The only subscale of the FIRST with a Cronbach’s alpha below 0.70 across most subgroups was living situation. The only exception was the African American families of early childhood students with EBD. The reason this subscale did not meet the criterion for satisfactory reliability for most groups is unclear. One possible explanation is that this FIRST subscale requires more attention to the entire family and social environment for a good assessment. The significant correlations of the living situation subscale, a measure of housing adequacy and stability, with neighborhood level economic indicators support this interpretation.

Moreover, the necessity of this subscale is supported by scholarship suggesting a significant role of family and social environment in the development of EBD in children (e.g., Agnafors et al., 2016; Brauner & Stephens, 2006; Raver & Knitzer, 2002; Xue et al., 2005). Past research on the psychometric properties of the FIRST yielded below satisfactory alpha coefficients for the family and community subscales (Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). The current study replicated this finding of low reliability on subscales tapping family and community stressors. Low internal consistency estimates for the subscales of family and community stressors is further evidence of the problems assessing family and social environment. Previous studies have shown that the living situation subscale in combination with the financial situation and physical health subscales produces a scale of basic life resources with adequate reliability (Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). The finding of differential reliability and validity estimates across these three scales raises questions about combing them into a single measure for some cultural groups.

Intake assessments may focus more on children’s functioning than on the entire family environment. Consistent with this perspective, significant discriminant validity was evident with a significant correlations between the child-focused subscales of parent–child (authority), parent–child (closeness), and child education and level of service, but smaller (nonsignificant) validity coefficients were found for the remaining FIRST subscales in relation to the same criterion variable.

A second possibility is that the living situation subscale is more susceptible to response bias. Along these lines, Cassidy et al. (2013) found a significant positive association between scores on the personal reaction inventory, a measure of social desirability, and scale scores in the resource section of the FIRST for their clinical subsample. Inclusion of a measure of social desirability in future studies of culturally-based differences in response styles can examine this possibility. Still, a third potential source of measurement error is the administration procedures in the current study. An inspection of data on date of FIRST assessments in the current study revealed instances of placements made before the FIRST was completed. It is recommended that FIRST assessments be completed within the first 2 weeks in intervention programs.

Another way to improve FIRST assessments is to have caseworkers trained in FIRST administration as a part of their job requirement. Steps to effective training in test administration includes a review of the instrument with questions directed to an expert administrator before using it; observing an experienced tester administer the instrument; administrating it under the supervision of a more experience tester; and finally independent test administration. These improvements in test administration may improve the psychometric properties of the FIRST which, in turn, would allow for a better test for ethnic/racial and developmental differences in resources and levels of stress in families with EBD children.

These findings indicate adequate overall reliability and limited validity of FIRST subscale scores. Limited validity has also been found in a previous study. Although Cassidy et al. (2013) found a statistically significant correlation between resource scores on the FIRST and social desirability, there was no association using the composite stressors score. It is important to note that the significant correlation reflected a small to medium effect size similar to validity coefficients in the current study. Thus limited validity of FIRST scores encourages further research on validity.

This is the first study to consider developmental differences in the psychometric qualities of FIRST scores. It extends past research on the psychometric properties of FIRST subscales (see Cassidy et al., 2013; Corliss et al., 2008). The child-focused scales tend to show better psychometric properties than those of addressing the entire family and social environment. Family environment is more important for early childhood students than older students with EBD. The current findings inadvertently add to the evidence of the limitations of direct assessments of the social and emotional development of young children (Hallam et al., 2014; Halle & Darling-Churchill, 2016). This argument can be extended to early childhood students with EBD.

Contrary to Burns (1996) hypothesis, the MANOVA results did not show significantly more severe scores, i.e., fewer resources and greater stressors, on the FIRST subscales for older EBD students relative to their early childhood counterparts. In a similar vein, Corliss et al. (2008) failed to find differences in severity of FIRST scores between EBD students in day treatment versus residential treatment. Both of these studies only administered the FIRST at one point in time. Multiple assessments with the FIRST may be necessary to uncover differences in resources and stressors at different levels of severity of EBD and concomitant treatment. Another consideration is that the FIRST may not have adequate discriminant validity for children with severe mental disorders. In other words, family assessments with the FIRST may have a ceiling effect among EDB students.

Implications

The recommendations are framed in the context of the service agency used in the study, but they are applicable to any mental health programs and professionals with similar results from using the FIRST. The FIRST appears to provide better information about the child than on the broader family and social environment. It would be important to see if caseworkers’ treatment plans for EBD students reflect this lack of attention to family and social environment. Supervision and training in how to overcome this problem is indicated. Caseworkers may need to use parents’ responses on the FIRST to probe for specific instances related to family and community stressors. The individual needs of an EBD child may overwhelm a parent or guardian to the point of overshadowing problems in the broader family and community context. Inclusion of education about the risks and stressors for EBD in pre service contacts or initial home visits by caseworkers also may help families better identify additional challenges in their lives. Systematic documentation of cultural and linguistic barriers by agency staff and the development of a strategy to address the issue may be required to improve reliability and validity of select FIRST subscales with culturally diverse families.

Conclusion

The current study suggests that ethnic/racial and developmental effects moderate the psychometric properties of the FIRST. It is unclear whether these effects are completely reliable and valid, given the potential sources of measurement error. Until response bias on the part of families and lack of standardization during test administration are both ruled out, the current findings of the moderating effects of ethnicity/race and developmental status should be accepted tentatively as sources of change in FIRST scores. The evidence, to date, reveals adequate reliability and limited validity of FIRST subscales. However, improvements of the FIRST in the assessment of families with EBD children should continue to be a goal of further research.

References

Agnafors, S., Svedin, C. G., Oreland, L., Bladh, M., Comasco, E., & Sydsjö, G. (2016). A biopsychosocial approach to risk and resilience on behavior in children followed from birth to age 12. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 48, 584–596.

Basten, M., Tiemeier, H., Althoff, R. R., van de Schoot, R., Jaddoe, V. W., Hofman, A., … van der Ende, J. (2016). The stability of problem behavior across the preschool years: An empirical approach in the general population. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 393–404.

Brauner, C. B., & Stephens, C. B. (2006). Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: Challenges and recommendations. Public Health Reports, 121, 303–310.

Burns, B. J. (1996). What drives outcomes for emotional and behavior disorders in children and adolescents? New Directions for Mental Health Services, 71, 89–102.

Cassidy, M. A., Lawrence, E. C., Vierbuchen, C. G., & Konold, T. (2013). Family inventory of resources and stressors: Further examination of the psychometric properties. Marriage & Family Review, 49, 191. doi:10.1080/01494929.2012.762441.

Corliss, B., Lawrence, E., & Nelson, M. (2008). Families of children with serious emotional disturbances: Parent perceptions of family resources and stressors. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 25, 271–285. doi:10.1007/s10560-008-0126-0.

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297–334.

Darling-Churchill, K. E., & Lippman, L. (2016). Early childhood social and emotional development: Advancing the field of measurement. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 1–7.

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 313–337.

Epstein, M. H. (1999). The development and validation of a scale to assess the emotional and behavioral strengths of children and adolescents. Remedial and Special Education, 20, 258–262.

Hallam, R. A., Lyons, A. N., Pretti-Frontczak, K., & Grisham-Brown, J. (2014). Comparing apples and oranges: The mismeasurement of young children through the mismatch of assessment purpose and the interpretation of results. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 34, 106–115.

Halle, T. G., & Darling-Churchill, K. E. (2016). Review of measures of social and emotional development. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 45, 8–18.

Lawrence, E. C. (2005). The family inventory of resources and stressors (FIRST) manual. Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia.

Muris, P., Mayer, B., Freher, N. K., Duncan, S., & van den Hout, A. (2010). Children’s internal attributions of anxiety-related physical symptoms: Age-related patterns and the role of cognitive development and anxiety sensitivity. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 41, 535–548.

Peterson, R. A. (1994). A meta-analysis of Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 381–391.

Raver, C. C., & Knitzer, J. (2002). Promoting the emotional well-being of children and families policy paper no. 3: Ready to enter: What research tells policymakers about strategies to promote social and emotional school readiness among three-and four-year old children. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty.

Whaley, A. L. (1990). A play technique to assess young children’s emotional reaction to personal events: A cognitive-developmental approach. Psychotherapy, 27, 256–260.

Xue, Y., Leventhal, T., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Earls, F. J. (2005). Neighborhood residence and mental health problems of 5- to 11-year-olds. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(5), 554–563.

Acknowledgements

Arthur L. Whaley was hired temporarily as a consultant to evaluate the funded project of the Astor Transition Program. This project was funded by a grant from the Robin Hood Foundation. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Michelle Santana with this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Whaley, A.L., DiMotta, R.J. & Walker, J. Psychometric Properties of the Family Inventory of Resources and Stressors in Families of Children with Emotional/Behavior Disorders: Ethnic/Racial and Developmental Differences. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35, 197–205 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0514-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-017-0514-4