Abstract

Black men are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer compared with White men. Despite advances in prevention and treatment strategies, disparities in prostate cancer among Black men persist. While research on the causes of higher incidence and mortality is ongoing, there is limited evidence in the existing literature that clearly speaks to the potential psychological or social factors that may contribute to disparities in prostate cancer incidence. Given the lack of attention to this issue, we review scientific evidence of the ways in which social factors, including socioeconomic status and racial segregation, as well as psychological factors, like depression and anxiety, are related to subsequent prostate cancer risk, which could occur through behavioral and biological processes. Our objective is to illuminate psychosocial factors and their context, using a racial disparity lens, which suggests opportunities for future research on the determinants of prostate cancer. Ultimately, we aim to contribute to a robust research agenda for the development of new prostate cancer prevention measures to reduce racial disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Historically, Black men in the USA have higher overall prostate cancer incidence rate compared to their White counterparts [1]. In 1990, the age-adjusted incidence was 25% higher among Blacks compared to Whites (223 vs. 173 per 100,000) [1]. Given recent advances in medicine, technology and educational efforts, overall prostate cancer incidence has sharply declined for the overall population (from 171 to 105 per 100,000 from 1990 to 2015) [1]. Nonetheless, Black men continue to bear a disproportional burden of prostate cancer risk, and this gap has widened, relatively and absolutely, over time: in 2015, Blacks had a 47% higher age-adjusted incidence rate compared to Whites (163 vs. 101 per 100,000) [1].

While age-adjusted data is a useful tool for comparing disease rates among populations, they are not measures of actual risk and can obscure inequities [2, 3]. Age-specific data can provide a more accurate picture of actual disease rates across groups, and age-specific comparisons are more useful for describing disparities across age groups. For instance, using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) data, we see significant racial differences in prostate cancer incidence in different periods of life [4]. As prostate cancer incidence rises with age for both Black and White men, racial disparities become more apparent, with the largest discrepancy among the youngest group (see Table 1). While the ratio among the youngest group declined between 1995 and 2010, it has again widened in 2015. The Black–White difference becomes larger from ages 50 to 64 (211 per 100,000 in 2015) to ages 65 to 74 (310 per 100,000 in 2015) and then declines for the oldest age group (55 per 100,000 in 2015) [4]. The reported incidence data may underestimate the actual rates, especially for Black men, due to lower levels of access to care and thus greater delays in diagnosis [5]. Even when Black individuals have access to healthcare, they are less likely to be advised about cancer screenings [6]. Experiences of racism in healthcare have been implicated as a cause for the low cancer screening rates [7].

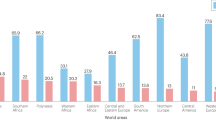

Reasons underlying the higher prostate cancer incidence among Black men are not fully understood and have received inadequate attention to date. Genetic predisposition is one potential factor underlying these disparities, and a non-comprehensive overview is presented below. However, we contend that while genetic factors may partially explain Black men’s higher risk, it is also critical to understand the potential psychological and social factors that may be additional underlying sources or factors that could trigger or exacerbate these disparities (Fig. 1) [8]. For instance, psychological and social factors may indirectly increase prostate cancer risk through biological and behavioral pathways [9], as it is the case with various chronic diseases [10]. In a proposed theoretical model for understanding disparities in prostate cancer, Ellison et al. [9] suggested that social stressors, including low socioeconomic status (SES), can increase the risk of prostate cancer through biological and behavioral pathways [9]. The purpose of this review is to summarize the available literature on psychosocial factors, including SES and racial segregation, as well as perceived stress and depression, that can contribute to prostate cancer risk. We argue that there is a need to broaden our thinking about potential risk factors that might affect prostate cancer risk among Black men beyond genetic influences, and we prioritize areas for future research that may help us better understand the sources of prostate cancer disparities.

Genetic factors (e.g., family history) and psychological (e.g., perceived stress) and social factors (e.g., segregation) may contribute to increase risk of physiological dysregulation and poor health behaviors that in turn increase the risk of prostate cancer for African (Black) Americans; SNS sympathetic nervous system, HPA hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis

Genetic factors that influence prostate cancer risk

Genetic predisposition has been studied as a potential explanatory factor for differences between Black and White men in prostate cancer risk. For example, family history of prostate cancer is a strong predictor, which suggests that this tumor may be at least in part hereditary [11,12,13]. Furthermore, the degree of relatedness appears to influence disease risk. Based on a review of 23 studies, Bruner et al. [12] found a pooled relative risk (RR) estimate of 1.93 for men with a history of prostate cancer in any relative, with a RR of 2.22 for those with an affected first-degree relative compared with 1.88 for an affected second-degree relative. Moreover, the risk is substantially higher for men with a brother who has had prostate cancer (RR: 2.87), as compared with those who have a father who has had prostate cancer (RR: 2.12). These findings suggest that genes, as captured by familial history, may contribute, at least partially, to prostate cancer risk and that the closer the relative, the higher the risk.

Emerging research suggests that there is a disproportionate burden of prostate cancer among Black men of West African ancestry in the USA, the Caribbean Islands, the UK and West Africa [14, 15]. A systematic review of 14 studies found that prostate cancer incidence is higher in countries connected by the Transatlantic Slave Trade (e.g., UK, Dominican Republic, Jamaica) relative to other groups in their respective countries who were not descendants of persons who were part of the slave trade. Consistent evidence regarding high incidence and poorer outcomes of prostate cancer among men of West African descent suggests that genetic factors may not only increase susceptibility to prostate cancer, but may also be related to its progression [14]. Some evidence suggests that genetic factors involved in the androgen pathway may partially underlie the elevated risk among men of African ancestry [16,17,18,19]. For example, the prostate cancer risk variant at 8q24 is common in men of African ancestry and could partly explain racial/ethnic disparities in prostate cancer incidence [20]. A meta-analysis of 10 studies also found that, after adjusting for relevant covariates (e.g., study type, participant age, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, and family history of prostate cancer), polymorphism in CYP17 was associated with increased prostate cancer risk among men of African ancestry [16]. Increasing evidence further suggests that epigenetic modifications are important contributors to prostate cancer development [21,22,23]. Notably, quantitative measures of the methylation status of prostate cancer tissues (using pyrosequencing) show that African-Americans have significantly higher methylation in prostate cancer-related genes compared to Caucasian men (AR, RARβ2, SPARC, TIMP3, and NKX2‑5) [23]. These results raise the possibility that persons of West African origin connected to the Slave Trade could also have common historic and/or contemporary exposures, as well as common responses to social or economic adversity that could lead to common epigenetic changes.

Expanding inquiry regarding prostate cancer disparities beyond genetic factors

The genetic and epigenetic factors reported above, along with others that are beyond the scope of this paper, may play a key role in prostate cancer risk and racial disparities. In parallel, exposure to social and economic adversities that men of African descent share (e.g., institutional discrimination, low SES) can also increase risk of prostate cancer through genetic mutations that arise from interaction between genes and psychosocial factors. Together, genealogical indicators including family history and ancestry not only reflect shared genes, but also shared environment and common and potentially modifiable risk factors [24]. An examination of these psychosocial determinants could expand understanding of disparities between Black and White men.

Psychosocial risks

Socioeconomic status

Socioeconomic status (SES) is the social standing or class of an individual or group, measured as education, income, wealth and occupation, or a combination of these factors [25]. In general, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations across the world exhibit a disproportionate burden of various diseases [26], including higher prostate cancer mortality rates [27, 28]. However, contrary to numerous studies documenting a positive gradient between SES and health [26, 29], prior work indicates that prostate cancer incidence is positively associated with SES indicators across all racial/ethnic subpopulations [30, 31]. For instance, analyses of data for 1973–2001 from the SEER-National Longitudinal Mortality databases show that higher (vs. lower) personal income and educational attainment are independently associated with higher prostate cancer incidence [30]. Furthermore, race appears to accentuate this gradient: in a large population-based cross-sectional study of 98,484 incident prostate cancer cases from California, African-American men had the highest incidence rates across all levels of individual-level SES [27].

Despite being highly correlated, the three individual components that are usually measured to define SES—income, education, and occupation—may have distinct effects on prostate cancer risk. For instance, higher education can provide greater access to social support, which can be an important buffer against psychosocial stressors [32], whereas higher income can provide greater access to quality healthcare [33]. In addition, certain occupations (e.g., firefighters), regardless of income and education, expose individuals to higher levels of carcinogens that may in turn increase disease risk [34,35,36]. Therefore, assessing the mechanisms by which these SES indicators raise prostate cancer risk is critical.

Income, education and occupation are valuable but not comprehensive measures of SES as they do not fully capture the economic resources that individuals have. For example, middle-class Blacks are more likely to live in poorer quality neighborhoods compared to their White counterparts [37]. Despite having a higher income than their neighbors, middle-class Blacks are still exposed to limited access to resources and goods that ultimately translate to wealth [38]. While income reflects the flow of money (i.e., the amount of money a person receives in return for service), wealth reflects ownership of assets [39]. Net worth, a measure of wealth, captures the economic assets and reserves that a household has [26]. Assets can include equity in homes, retirement accounts, stocks, and bonds, taking into account debt [40]. Studies find that wealth is a significant predictor of health, even after controlling for other indicators of SES [40, 41]. As Williams and colleagues suggested, wealth facilitates the ability of a household to both plan for the future and cushion shortfalls in income [26]. For every dollar of wealth that Whites have, Asian households have 83 cents, but Blacks have 6 cents and Hispanics have 7 cents [42]. There are significant racial disparities in wealth, where White families amass a net worth of $105 k compared to less than $5 k for Black families [43]. Disparities in wealth can contribute to disparities in prostate cancer incidence through psychosocial and behavioral mechanisms [43]. Future research should comprehensively capture other forms of objective SES, including wealth, neighborhood economic status, purchasing power of income, level of consumer debt [44] to better understand the relationship between race, SES, and prostate cancer incidence.

Furthermore, SES is a multi-dimensional construct that also captures differential access to psychosocial resources and adversity, along with economics and power, all of which have deep influence on health [26, 45]. In fact, it has been proposed that, in addition to “objective” or traditional measures of SES (e.g., income, education, occupation), individuals’ “subjective” SES, or their perception of their current and future position in society compared to others, is associated with physical health, beyond the role of objective SES, as found in a meta-analysis of 31 studies [46]. Importantly, this review of research found comparable effects in men and women adults, but stronger effects among Blacks as compared to Whites [46]. However, there is a paucity of research on the relationship between subjective SES and cancer incidence specifically. It is possible that lower subjective SES leads to psychological distress and negative coping strategies that, in turn, compromise a person’s physical health [47]. While the psychobiological pathways that link objective and subjective SES factors with physical health remains unclear, future research in this area may provide additional insights about racial disparities in prostate cancer incidence.

Segregation

Residential segregation—the spatial separation of various groups, based on common characteristics, into neighborhood contexts that shapes their living environment [48]—has been identified as one of the most important social determinants of health disparities among racial/ethnic minorities [38]. Generally, Blacks in the USA live in highly segregated areas, which tend to have high levels of poverty, limited education and employment opportunities, poor housing quality and neighborhood safety, as well as reduced healthcare access and quality [38]. Furthermore, segregation results in restricted access to societal goods and resources, including pollutant-free environments, healthy foods, and recreational facilities that may influence carcinogenesis [45, 49, 50]. While SES captures certain aspects of segregation (e.g., limited educational opportunities), it does not capture community-level effects of health. For instance, poor Whites are more likely to live among non-poor residents, whereas most poor Blacks live in high-poverty areas [38, 51]. Those who reside in more disadvantaged neighborhoods are more likely to have cumulative biological risk factors (e.g., higher levels of inflammation) compared to those in less disadvantaged neighborhoods, even after adjusting for traditional indicators of SES [52, 53].

A recent systematic review of 17 studies found that segregation contributed significantly to racial cancer disparities as well, even after controlling for SES and health insurance [54]. Specifically, residing in Black segregated areas was associated with higher odds of later-stage diagnosis of breast and lung cancers, higher mortality rates and lower survival rates from breast and lung cancers, and higher cumulative cancer risks associated with exposure to ambient air toxics [54]. Yet, no relationship between segregation with prostate cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis, although only two studies were conducted on this topic [54]. For example, one study, using data from the SEER of 412,482 individuals, revealed that lower-income and less segregated areas explained Black-White racial disparities of early-stage diagnosis of colorectal and breast cancer. However, there was no evidence that area characteristics explained racial disparities of early-stage diagnosis of prostate cancer [55].

Multiple risk factors unfolding from living in segregated areas could subsequently lead to prostate cancer risk. Therefore, their mediating role could explain the absence of direct associations between segregation and prostate cancer risk in prior studies. Landrine and Corral suggest that higher environmental exposures to toxins and residence in poorer built environments in segregated neighborhoods may contribute to racial disparities in cancer [56]. For instance, some preliminary evidence hint at higher traces in the blood of the heavy metal cadmium—a risk factor for prostate cancer [57]—among Blacks compared to Whites [58, 59]. However, the two studies focusing on segregation and prostate cancer did not consider variations in environmental toxins and access to care as potential mediators. Future research should comprehensively delineate these segregation-related factors, as well as other psychosocial stressors (e.g., housing quality, crimes) to better understand the effects of segregation on racial differences in prostate cancer incidence. Altogether, given the limited empirical attention to SES, segregation, and prostate cancer, there is a need to replicate earlier findings and to better understand the conditions under which these factors might contribute to disease risk.

Psychological factors

Psychological symptoms, including anxiety and depression, are inversely associated with health [10, 60]. Such unfavorable factors vary by SES and race/ethnicity, with socially disadvantaged groups and racial/ethnic minorities experiencing a higher levels of psychological distress [61,62,63]. Psychological factors have been established as important contributors to cardiovascular disease risk [64], while the association of psychological factors with cancer risk has revealed inconsistent findings, their association with prostate cancer incidence specifically and related disparities remain largely understudied [60].

Meta-analyses of large epidemiologic cohort studies concluded that depression as a disorder presents a small increase in the risk for all-cause cancer [65,66,67], although null findings have also been observed [60, 68, 69]. However, there is little evidence that depression plays a significant role in the onset prostate cancer specifically. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 25 prospective studies on depression and subsequent cancer risk found that the six studies that focused on major depressive disorder and prostate cancer incidence found no evidence of an association [67]. Some studies have shown that anxiety symptoms increase as men come closer to learning their diagnosis [70, 71]. It may be that men with a family history of prostate cancer, and therefore, a greater risk of prostate cancer, have greater anxiety during the time of medical investigation and diagnosis. In one of the rare prospective studies, Nielsen and colleagues [72] found no association after a 20-year follow-up between the intensity and frequency of certain bodily sensations related to anxiety (e.g., tension, nervousness, impatience, sleeplessness) at baseline (1981–1983) and prostate cancer incidence (2002) in 5,496 men enrolled in the Copenhagen City Heart Study. However, given that the studies are limited to homogeneous samples of White men the specific role of anxiety and depression for the risk of developing prostate risk over time remains unclear, particularly with regard to racial/ethnic minority populations.

Some studies that have examined the association of perceived stress and prostate cancer onset yield suggestive associations. For example, in a case-control study of 3,103 incident cancer cases, Canadian participants were asked to retrospectively recall how stressful each job was that they had held for ≥ 6 months over their lifetime and whether the job(s) made them feel tense or anxious most of the time [73]. Compared to those who never experienced perceived stress at work, men who did for a cumulative duration of 15–30 years had a marginally significant greater prostate cancer risk (odds ratio = 1.48; confidence intervals = 0.98–2.23) after adjusting for relevant confounders, while durations of 1–15 years and > 30 years were unrelated [73]. In a prospective study of 5,743 Scottish men, having high or medium levels of general perceived stress—as measured by the Reeder Stress Inventory [74]—was moderately associated with increases in prostate cancer risk 30 years later (hazard ratio: 1.65, 95% CI 1.20–2.27) [75]. Another study found that among 139 men in Argentina, stressful life events—measured using Holmes and Rahe’s Social Readjustment Scale [76]—was not associated with PSA levels [77]. However, cortisol, which captures physiological stress arousal, moderated the relationship: among men with low cortisol, perceived stress was inversely associated with PSA levels, whereas perceived stress was positively associated with PSA levels in men with high cortisol. According to the authors, individuals unable to adapt to environmental demands may be more susceptible to prostate cancer because of the inability to mount an appropriate immunologic response to neoplastic cells. Participants with high cortisol may experience greater chronic perceived stress, possibly resulting in the suppression of cellular immune activity, leading to an increase in PSA levels [77]. In this study, cortisol was obtained from blood, it has been argued that salivary cortisol sampling would provide more accurate results because it is unbound by corticosteroid-binding globulin and other proteins, making it a measure of “free” cortisol [78]. Also, obtaining salivary cortisol samples is more feasible that blood samples, allowing researchers to capture diurnal rhythm of cortisol [78]. Thus, using larger sample sizes and considering salivary cortisol may provide a more accurate assessment of the complex interaction between perceived stress, biological measures of stress arousal, and prostate cancer risk.

The understanding of the link between psychosocial factors and prostate cancer risk remains understudied due to the paucity of research that applies the appropriate conceptualization and measurement protocols to capture the effects of psychosocial stressors and related distress on prostate cancer risk. For example, while the Reeder Stress Inventory mentioned above [74, 75] captures stress appraisal (i.e., person’s perception that the external demands exceed their ability to cope), the scale does not capture the type/source of stressor that is being appraised nor does it capture the severity and chronicity of the specific stressor. Conversely, the Social Readjustment Rating Scale used previously [76] lists 43 stressful life events that may have occurred in the last year. These are meant to capture experiences of acute stressors within a limited time frame (i.e., within the last year). Investigators add the values corresponding to the life events reported by the participants; if a particular event happened more than once, researchers multiply the value by the number of occurrences. While the scale captures a broad range of potential stressors (e.g., sexual difficulties, being fired at work), as well as accounts for chronicity, it does not consider participants’ stress appraisal of the events, life course exposure to stressors, chronic ongoing stressors in major roles and domains of life, nor does it consider the participants’ life stage (i.e., certain age groups may not have experienced retirement) [79].

Furthermore, these studies did not assess differences in perceived stress and the potential impact on men’s health across diverse racial groups. This empirical question remains critical, given that racial and ethnic minorities experience greater exposure to stress across the broad range of stressors. Racial ethnic minorities are not only exposed to greater individual stressors (e.g., unsafe neighborhoods), they are also exposed to a greater clustering of stressors over time [80]. For example, racial/ethnic minorities report more frequent experiences of unfair treatment, often referred to as perceived discrimination, compared to Whites. It has been suggested that perceived discrimination can generate additional stressors (e.g., marital conflict, social isolation), which can lead to greater adverse health outcomes [81]. Perceived discrimination, particularly among racial/ethnic minorities, has been shown to erode an individual’s health [82, 83], notably by promoting physiologic dysregulation [84, 85]. For instance, in a sample of 233 African-Americans, chronic experiences of unfair treatment are associated with allostatic load, a multisystem index of biological dysregulation that includes cardiovascular regulation, lipid, glucose, inflammation, SNS, parasympathetic nervous system, HPA axis [85]. Unfair treatment may also erode an individual’s health through biological (e.g., release of cortisol) [86] and behavioral responses (e.g., tobacco use) [87] that are potentially involved in carcinogenesis. Yet, little is known about whether chronic experiences of unfair treatment may increase prostate cancer risk specifically. Unfair treatment is just one of many psychosocial stressors racial/ethnic minorities disproportionately experience. Because racial/ethnic minorities report higher levels of multiple stressors, like financial strain, neighborhood disorder, and relationship stressors, and greater clustering of these stressors [80], they are at an increased risk of health-damaging behaviors and immune dysfunction [88]. The link between the co-occurrence of multiple stressors and prostate cancer risk remains unknown. Measuring stressors and their distress response comprehensively would allow us to better understand the extent to which they, synergistically, have an impact on prostate cancer development and its potential contribution to racial disparities in prostate cancer outcomes.

Despite the very little attention in this area [89], work on John Henryism, which is an active strategy aiming to succeed against all odds [90, 91], is worth noting. In fact, the prolonged effort coping with high demands and other psychosocial stressors may increase the risk of adverse health effects, particularly for marginalized group members [90,91,92]. Although there is mounting evidence that John Henryism is associated with high blood pressure among low SES Black men and persons who lack the resources to facilitate success [93] less is known of its relationship with cancer risk, including prostate tumors. In a case-control study of 400 prostate cancer cases (160 African-American; 240 Caucasian) and 385 controls (161 African-American; 224 Caucasian), higher John Henryism levels were associated with greater odds of prostate cancer risk (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.11–2.40), particularly for those with low social support and those with high stress levels—measured by the Perceived Stress Scale [94]. While racial differences were not found, further research addressing the study’s limitations should be conducted. Notably, these participants were asked to recall experiences of perceived stress, stressors, coping, and social support prior to developing prostate cancer, which may introduce recall bias. Further, the Perceived Stress Scale [95] is widely used to measure the perception of stress, but does not capture the nature nor the chronicity of stressors, which appear particularly relevant when investigating John Henryism.

Emotion regulation

How someone copes with external demands is another critical facet of psychological functioning. In previous research targeting cancer outcomes, one regulatory strategy investigated is emotional control that is the tendency to minimize emotional upset and/or suppress the expression of negative emotions. While anger control has been primarily evaluated as a determinant of breast cancer risk [96], its impact on prostate cancer risk has been considered in only one prospective cohort study to our knowledge. Among 19,730 Australian adults, greater anger control was positively associated with prostate cancer development over 9 years after adjusting for education level (hazard ratio = 1.17, 95% CI 1.04–1.30), suggesting that minimizing/suppressing anger may play a small role in prostate cancer risk [97]. However, from these results it remains unknown whether similar effects of anger regulation on prostate cancer risk would be evident in Blacks, and if so, of greater magnitude than in Whites. Nonetheless, prior disparities work targeting other health outcomes is suggestive. For instance, in the MIDUS cohort, African-Americans reported higher levels of anger-out—another strategy consisting in expressing anger outwardly—compared to their White counterparts, which was related to greater inflammation levels [98].

The regulation of emotions other than anger has been overlooked in relation to cancer incidence. Yet, a study has reported a marginally significant increased risk in all-cause cancer mortality (HR = 1.70; CI 1.00, 2.88; p < .05) over a 12-year period in 729 adults (81% White; 46% men) who had higher versus lower levels of emotional suppression [99]. Of note, the number of deaths was somewhat small (all-cause = 111; cancer = 34), reducing the statistical power to detect associations and the stability of the estimates. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined whether cancer racial disparities relate to other regulation strategies, but such associations have been documented with other health-related outcomes. For example, one study revealed that African-Americans who endorse a defensive responding style (correlated with repressing one’s emotions) have significantly worse scores on a composite of health outcomes including heart disease, stroke and hypertension, compared to European Americans [100]. Because cardiometabolic diseases and cancer may have some common etiological roots and share biobehavioral pathways [101, 102], the investigation of emotion regulation as a determinant of prostate cancer onset remains warranted.

Psychosocial resilience and resources

Psychological well-being

Studies to date have mainly focused on negative emotional states, particularly anxiety, depression and anger. Emerging evidence suggests that positive emotion-related factors, including optimism, purpose in life, life satisfaction, and emotional vitality, are associated with a reduced risk of hypertension and cardiovascular disease, independently of negative emotional factors [103, 104]. Limited research has been conducted with regard to cancer incidence. In the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (n = 8,182), overall well-being as measured by the CASP-19 [105] was unrelated to self-reported diagnoses of cancer over an 8-year period, after adjusting for sociodemographics, health status and behaviors, and depressive symptoms [106]. When considering specific psychological well-being factors, results from the EPIC Germany cohort (n = 48,411) suggested lower (vs. higher) levels of life satisfaction were associated with greater cancer risk among women, but not men, in the following 8 years, after adjusting for potential covariates [107]. However, both studies did not assess prostate cancer risk specifically nor other dimensions of psychological well-being (e.g., optimism, life purpose). Moreover, they were unable to investigate potential racial disparities. However, accumulating evidence hints to psychological well-being as an avenue worth pursuing in the area of prostate cancer risk and disparities. For instance, dimensions of psychological well-being (e.g., positive affective states like happiness; optimism) are associated with adoption of healthier behaviors (e.g., physical activity) [108] and more favorable biological processes (e.g., lower levels of inflammation) [10]. Prior findings have suggested that optimism and life satisfaction were significantly lower among Blacks versus Whites, whereas positive affect was significantly higher [109]. Therefore, investigating the association of multiple psychological well-being factors with prostate cancer risk across racial groups, along with potential biobehavioral mechanisms, remains highly relevant.

Biobehavioral consequences of psychosocial factors

In response to psychosocial factors, individuals may also engage in unhealthy behaviors, to enhance their ability to cope with a stressor or handle negative emotions [110,111,112]. For instance, depression is associated with a greater likelihood of physical inactivity, alcohol and tobacco consumption, overweight/obesity as well as unfavorable diet and weight gain up to 18 years later [113, 114]. In turn, those who are obese and are engage in unhealthy lifestyle factors are more likely to be diagnosed with prostate cancer [115]. Such unhealthy habits may also be modifiable risks associated with prostate cancer incidence or advanced prostate cancer [8, 116,117,118,119,120,121]. In fact, in a large prospective study with White males, those who reported less favorable habits in terms of physical activity, diet, alcohol consumption, and smoking had a 21–40% increased incidence of fatal prostate cancer compared to those with more favorable lifestyle behaviors [122]. Few Black–White differences have been observed thus far with regard to the role of lifestyle factors in prostate cancer risk [123]. However, studies show that Black men tend to be less physically active and report lower diet quality (e.g., consuming a higher percentage of energy from refined carbohydrates, and a higher intake of sweetened beverages) compared to their White counterparts [8, 121], thus increasing the risk of prostate cancer for Black men. Because of the disproportionate burdens racial/ethnic minorities experience, Black men may engage in these behaviors largely to cope with psychosocial stressors [124, 125]. It remains unknown whether psychosocial factors may impact prostate cancer risk through behavioral (and/or biological) pathways similarly across racial/ethnic groups. Therefore, knowing that minorities are likely to experience greater life adversities and higher psychological distress compared to Whites, this area of research certainly deserves more attention.

Psychosocial stressors evoke emotional distress responses, such as depressive mood states, that can activate physiological systems [126,127,128]. The continual activation of these physiological systems can disrupt their function and deplete the body’s immune system to defend against cancerous cells [9, 129, 130]. Such dysregulation due to chronic stressors and distress is often referred to as allostatic load and is characterized by elevated (or suppressed) physiological activity across multiple regulatory systems, including cardiovascular and metabolic processes, immune system, sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic pituitary–adrenal axis [131,132,133,134]. Black middle and older-aged adults have greater allostatic load, compared to their White counterparts [132, 135]. This difference is presumed to be due to disproportionate burden of adversities across the lifecourse [136, 137]. Further examination is needed on the biological underpinnings of psychosocial stressors and prostate cancer risk.

A lifecourse perspective

To comprehensively understand the role of psychosocial factors in prostate cancer risk and racial disparities, future studies should examine a broad range of stressors using a lifecourse perspective, taking into account the timing, source, setting, chronicity and severity of the stressors [10, 45]. The stressors assessed to date have not been comprehensive—and research finds that limited assessment understates the effects of stressors on health [79]. Varying stress exposure and vulnerability at certain life stages can have an impact on later health. For example, early childhood adversities (e.g., family economic hardship, parents having marital problems) are associated with cardiovascular disease and premature cellular aging in adulthood [138,139,140]. Life adversity and clinical psychological distress are known to be associated with a greater vulnerability to experience similar adversities and distress later on. The accumulation of these stressors across the lifespan significantly increase immune system impairment and, therefore, increase the risk for disease [141]. With regard to racial disparities, a recent study using data from a nationally representative panel found that greater exposure to childhood adversity explained racial health disparities in self-reported health, morbidity, and functional limitation in adulthood among men, with some of this effect appearing to operate through the lasting influence of childhood adversity on relationship strain and socioeconomic deprivation in adulthood [142]. Researchers suggest that cancer risk may be influenced by exposure to stressful conditions and events early on in life [2, 143]. However, there is a need to examine the influence of childhood adversity on the risk of prostate cancer specifically. Taking a lifecourse perspective that places greater emphasis on early life factors, such as living in high-risk environments (e.g., community violence), and identifying how these early factors combine, additively or interactively, with other exposures over the lifecourse to increase prostate cancer risk in early, middle and later life could provide insight into existing patterns of disparities and possible prevention strategies [144].

Prevention efforts are still needed

As future research continues to examine the relationship between psychosocial factors and prostate cancer risk, prevention efforts need to be continually implemented and enhanced. Racial disparities in prostate cancer can be reduced with coordinated and sustained efforts to provide high-quality prevention, screening and treatment to all segments of the population [145, 146]. Prevention can take the form of lifestyle changes such as healthy nutrition and high levels of physical activity [147, 148]. Racial differences in diet and physical activity are important factors to consider in prostate cancer incidence [8, 149]. While healthy diet and exercise, if adopted, can help lower the risk of prostate cancer, more effort is needed to promote exercise and healthy dietary behaviors earlier in life to have greater impact at reducing racial/ethnic disparities in disease risk [150]. We further maintain that there is greater need to tailor these lifestyle modification interventions to address known barriers to health dietary behaviors and physical activities, including lack of access to healthy food and exercise facilities, among Black men [151].

Other social factors, not covered in detail herein, also deserve more empirical attention to provide insight for future interventions. Notably, Black men compared with other racial groups exhibit a lack of knowledge and awareness about prostate cancer [152], which can increase the risk of late detection of prostate cancer at an advanced disease stage [153]. For example, in a community-based sample of 290 Black men, approximately 60% did not know that Black men were more likely than their White peers to develop prostate cancer, whereas 45% thought that if they had prostate cancer it would kill them, and another 28% were not certain [154]. Black men with a family history of prostate cancer have greater knowledge of prostate cancer than Black men with no family history of prostate cancer [155, 156]. However, the level of knowledge among men may depend on education and income level [154, 155], making it particularly relevant as a potential target to address racial disparities. Besides knowledge and awareness, inadequate access to services, mistrust of the health system, poor relationships with medical providers and perceived threats to male sexuality further appeared as major barriers to receiving prostate care [157]. Additional research will help to understand these barriers and identify opportunities for interventions, future work should also seek to develop better tools for screening and to ensure timely and adequate follow-up of screening and treatment. A community-based participatory approach, whereby interventions are developed in conjunction with health providers, community members and relevant stakeholders can help identify previously undetected barriers and resources in the community, and develop new approaches to incorporating community members’ psychosocial context in healthcare screening and prevention [157].

Conclusion

Black men have suffered a disproportionate burden of prostate cancer, compared to White men, and this has persisted despite advances in interventions and prevention measures. We examined underlying factors that lead to the disparate experience of prostate cancer among Black men by focusing on the psychosocial context, which allows us to highlight the complex interaction between social and psychological factors, and related biobehavioral processes (see Fig. 1). Previous evidence of the independent effect of these factors on prostate cancer risk factors points to the crucial need to comprehensively examine how these factors may interactively impact prostate cancer risk. For instance, while findings on the association between SES and prostate cancer incidence were mixed, psychological factors may help in part to explain how this relationship varies by race.

There are considerable limitations that need to be addressed to build a stronger evidence of the interrelationships, if any, between SES, psychological factors, and prostate cancer risk. Firstly, the dimensions of SES are distinct aspects of social and economic position, income, education and occupation. Each dimension of SES may operate differently to increase the risk of prostate cancer. Future research should examine and compare their respective influence. Other dimensions of social and economic position, such as wealth, has not been examined in relation to prostate cancer risk specifically, but can provide greater insight into existing related disparities. Secondly, studies have not captured well the multidimensional or cumulative nature of psychosocial stressors. The measures used in many of the studies have not accounted for the source, severity, clustering and chronicity of the stressors [10, 37], nor the type of stressors that disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities (e.g., racial discrimination) [158]. Given that many studies are cross-sectional or retrospective, there is a need for future research to take a lifecourse approach to identify potential critical periods when stressor exposure, including SES and psychological factors, may increase the risk of prostate cancer later in life.

Thirdly, with regard to potential mechanisms, there have been no studies, thus far, that have examined the role that allostatic load may play in the association between stress-related exposures, including SES and psychological factors, and prostate cancer risk. Findings from such future studies, along with those investigating behavioral processes, will likely help elucidate causes of prostate cancer disparities. Fourthly, we found that most studies on the various factors associated with prostate cancer risk have been conducted outside the USA, limiting conclusions that can be drawn to American men. Also, of the US-based studies on prostate cancer risk factors, few focused on Black Americans. Nonetheless, the contextual differences by race are so pronounced that they cannot be ignored when discussing prostate cancer disparities. Racial segregation was not associated with prostate cancer in the only two studies that explicitly examined this question, but it remains a strong social determinant of cancer [33].

Altogether, further research is needed to first replicate preliminary associations of psychosocial factors with prostate cancer risk presented in this review, and then to better understand the extent to which genetics and biobehavioral pathways may contribute to disparities in cancer incidence. Future research on understanding prostate cancer risk factors can address previous methodological limitations by conducting prospective studies with large and diverse samples, using comprehensive assessment of stress-related exposures, and drawing on a lifecourse approach to capture the myriad of factors that ultimately increases the risk of prostate cancer.

References

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) age-adjusted SEER incidence rates by race/ethnicity, prostate, all ages, male 1975–2014 (SEER 9). https://seer.cancer.gov/faststats

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Shields AE (2016) Understanding and effectively addressing breast cancer in African American women: unpacking the social context. Cancer 122:2138–2149. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29935

Fu M, Todem D, Fu WJ, Ma S (2014) A millennium bug still bites public health—an illustration using cancer mortality. http://arxiv.org/abs/1401.7686. Accessed 21 Mar 2019

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program age-specific (Crude) SEER incidence rates, by race/ethnicity, prostate, all ages, male, 2010–2014. https://seer.cancer.gov/explorer/. Accessed 21 Mar 2019

DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG et al (2016) Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA Cancer J Clin 66:290–308. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21340

Dean LT, Subramanian SV, Williams DR et al (2015) Getting Black men to undergo prostate cancer screening: the role of social capital. Am J Mens Health 9:385–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988314546491

Shariff-Marco S, Klassen AC, Bowie JV (2010) Racial/ethnic differences in self-reported racism and its association with cancer-related health behaviors. Am J Public Health 100:364–374. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163899

Cockerham WC, Bauldry S, Hamby BW et al (2017) A comparison of Black and White racial differences in health lifestyles and cardiovascular disease. Am J Prev Med 52:S56–S62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.019

Ellison GL, Coker AL, Hebert JR et al (2001) Psychosocial stress and prostate cancer: a theoretical model. Ethn Dis 11:484–495

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Qureshi F, Appleton AA, Kubzansky LD (2017) A healthy mix of emotions: underlying biological pathways linking emotions to physical health. Curr Opin Behav Sci 15:16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.003

Madersbacher S, Alcaraz A, Emberton M et al (2011) The influence of family history on prostate cancer risk: implications for clinical management. BJU Int 107:716–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10024.x

Bruner DW, Moore D, Parlanti A et al (2003) Relative risk of prostate cancer for men with affected relatives: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 107:797–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.11466

Johns LE, Houlston RS (2003) A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial prostate cancer risk. BJU Int 91:789–794

Odedina FT, Akinremi TO, Chinegwundoh F et al (2009) Prostate cancer disparities in Black men of African descent: a comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among Black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infect Agent Cancer 4:S2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-4-S1-S2

Rebbeck TR, Devesa SS, Chang B-L et al (2013) Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of African descent. Prostate Cancer 2013:e560857. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/560857

Taioli E, Sears V, Watson A et al (2013) Polymorphisms in CYP17 and CYP3A4 and prostate cancer in men of African descent. Prostate 73:668–676. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.22612

Aiken WD (2011) Historical determinants of contemporary attributes of African descendants in the Americas: the androgen receptor holds the key. Med Hypotheses 77:1121–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2011.09.017

Reams RR, Kalari KR, Wang H et al (2011) Detecting gene-gene interactions in prostate disease in African American men. Infect Agent Cancer 6:S1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-9378-6-S2-S1

Farrell J, Petrovics G, McLeod DG, Srivastava S (2013) Genetic and molecular differences in prostate carcinogenesis between African American and Caucasian American men. Int J Mol Sci 14:15510–15531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140815510

Haiman CA, Patterson N, Freedman ML et al (2007) Multiple regions within 8q24 independently affect risk for prostate cancer. Nat Genet 39:638–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng2015

McGinley KF, Tay KJ, Moul JW (2016) Prostate cancer in men of African origin. Nat Rev Urol 13:99–107. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2015.298

Goh LK, Liem N, Vijayaraghavan A et al (2014) Diagnostic and prognostic utility of a DNA hypermethylated gene signature in prostate cancer. PLoS ONE 9:e91666. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091666

Kwabi-Addo B, Wang S, Chung W et al (2010) Identification of differentially methylated genes in normal prostate tissues from African American and Caucasian men. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 16:3539–3547. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3342

Kiciński M, Vangronsveld J, Nawrot TS (2011) An epidemiological reappraisal of the familial aggregation of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 6:e27130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027130

Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM (2014) Social epidemiology. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson N (2016) Understanding associations between race, socioeconomic status and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol 35:407–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242

Cheng I, Witte JS, McClure LA et al (2009) Socioeconomic status and prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates among the diverse population of California. Cancer Causes Control 20:1431–1440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-009-9369-0

Kilpeläinen TP, Talala K, Raitanen J et al (2016) Prostate cancer and socioeconomic status in the finnish randomized study of screening for prostate cancer. Am J Epidemiol 184:720–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww084

Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P (2010) Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 51:S28–S40

Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Miller BA et al (2008) Impact of socioeconomic status on cancer incidence and stage at diagnosis: selected findings from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results: National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Cancer Causes Control 20:417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-008-9256-0

Liu L, Cozen W, Bernstein L et al (2001) Changing relationship between socioeconomic status and prostate cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 93:705–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/93.9.705

Zimmerman EB, Woolf SH, Haley A (2015) Understanding the relationship between education and health: a review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives. Population health: behavioral and social science insights. Agency for Health-care Research and Quality, Rockville, pp. 347–384

Dickman SL, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S (2017) Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet 389:1431–1441

Tsai RJ, Luckhaupt SE, Schumacher P et al (2015) Risk of cancer among firefighters in California, 1988–2007. Am J Ind Med 58:715–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22466

Zeegers MP, Friesema IH, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA (2004) A prospective study of occupation and prostate cancer risk. J Occup Environ Med 46:271–279

Sparer EH, Prendergast DP, Apell JN et al (2017) Assessment of ambient exposures firefighters encounter while at the fire station: an exploratory study. J Occup Environ Med 59:1017–1023. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001114

Alba RD, Logan JR, Stults BJ (2000) How segregated are middle-class African Americans? Soc Probl 47:543–558

Williams DR, Collins C (2001) Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep 116:404–416

Baum F (2005) Wealth and health: the need for more strategic public health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 59:542–545

Boen C, Yang YC (2016) The physiological impacts of wealth shocks in late life: evidence from the great recession. Soc Sci Med 150:221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.12.029

Hajat A, Kaufman JS, Rose KM et al (2010) Do the wealthy have a health advantage? Cardiovascular disease risk factors and wealth. Soc Sci Med 71:1935–1942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.027

US Census Bureau (2014) Wealth and asset ownership. https://www.census.gov/topics/incomepoverty/wealth.html. Accessed 21 Mar 2019

Brown TH (2016) Diverging fortunes: racial/ethnic inequality in wealth trajectories in middle and late life. Race Soc Probl 8:29–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-016-9160-2

Pollack CE, Chideya S, Cubbin C et al (2007) Should health studies measure wealth?: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 33:250–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.033

Williams DR, Mohammed SA, Leavell J, Collins C (2010) Race, socioeconomic status, and health: complexities, ongoing challenges, and research opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186:69–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05339.x

Cundiff JM, Matthews KA (2017) Is subjective social status a unique correlate of physical health? A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000534

Demakakos P, Nazroo J, Breeze E, Marmot M (2008) Socioeconomic status and health: the role of subjective social status. Soc Sci Med 67:330–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.038

Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV (2003) Future directions in residential segregation and health research: a multilevel approach. Am J Public Health 93:215–221. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.215

Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR et al (2008) Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med 34:16–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.021

Galvez MP, Morland K, Raines C et al (2008) Race and food store availability in an inner-city neighbourhood. Public Health Nutr 11:624–631. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007001097

Firebaugh G, Acciai F (2016) For blacks in America, the gap in neighborhood poverty has declined faster than segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607220113

Barber S, Hickson DA, Kawachi I et al (2016) Neighborhood disadvantage and cumulative biological risk among a socioeconomically diverse sample of African American adults: an examination in the Jackson Heart Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 3:444–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-015-0157-0

King KE, Morenoff JD, House JS (2011) Neighborhood context and social disparities in cumulative biological risk factors. Psychosom Med 73:572–579. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318227b062

Landrine H, Corral I, Lee JGL et al (2016) Residential segregation and racial cancer disparities: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Dispar. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-016-0326-9

Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE et al (2008) Racial segregation and disparities in cancer stage for seniors. J Gen Intern Med 23:699–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0545-9

Landrine H, Corral I (2009) Separate and unequal: residential segregation and black health disparities. Ethn Dis 19:179

Ju-Kun S, Yuan D-B, Rao H-F et al (2016) Association between Cd exposure and risk of prostate cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002708

Mijal RS, Holzman CB (2010) Blood cadmium levels in women of childbearing age vary by race/ethnicity. Environ Res 110:505–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2010.02.007

Aoki Y, Yee J, Mortensen ME (2017) Blood cadmium by race/hispanic origin: the role of smoking. Environ Res 155:193–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.02.016

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Chen Y, Singh A et al (2016) Psychiatric, psychological, and social determinants of health in the Nurses’ Health Study Cohorts. Am J Public Health 106:1644–1649. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303318

Matthews KA, Gallo LC, Taylor SE (2010) Are psychosocial factors mediators of socioeconomic status and health connections? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186:146–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05332.x

Myers HF (2009) Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: an integrative review and conceptual model. J Behav Med 32:9–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4

Evans GW, Kim P (2010) Multiple risk exposure as a potential explanatory mechanism for the socioeconomic status–health gradient. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1186:174–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05336.x

Everson-Rose SA, Lewis TT (2005) Psychosocial factors and cardiovascular diseases. Annu Rev Public Health 26:469–500. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144542

Oerlemans ME, van den Akker M, Schuurman AG et al (2007) A meta-analysis on depression and subsequent cancer risk. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health CP EMH 3:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-3-29

McGee R, Williams S, Elwood M (1994) Depression and the development of cancer: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 38:187–192

Jia Y, Li F, Liu YF et al (2017) Depression and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health 149:138–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.04.026

Sun H-L, Dong X-X, Cong Y-J et al (2015) Depression and the risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP 16:3233–3239

Ahn HK, Bae JH, Ahn HY, Hwang IC (2016) Risk of cancer among patients with depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and implications. Psychooncology 25:1393–1399. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4084

Medd JCC, Stockler MR, Collins R, Lalak A (2005) Measuring men’s opinions of prostate needle biopsy. ANZ J Surg 75:662–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03477.x

Dillard AJ, Scherer LD, Ubel PA et al (2017) Anxiety symptoms prior to a prostate cancer diagnosis: associations with knowledge and openness to treatment. Br J Health Psychol 22:151–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12222

Nielsen NR, Kristensen TS, Zhang Z-F et al (2007) Sociodemographic status, stress, and risk of prostate cancer. A prospective cohort study. Ann Epidemiol 17:498–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.02.001

Blanc-Lapierre A, Rousseau M-C, Weiss D et al (2017) Lifetime report of perceived stress at work and cancer among men: a case-control study in Montreal, Canada. Prev Med 96:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.12.004

Metcalfe C, Smith GD, Wadsworth E et al (2003) A contemporary validation of the Reeder Stress Inventory. Br J Health Psychol 8:83–94. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910703762879228

Metcalfe C, Smith GD, Macleod J, Hart C (2007) The role of self-reported stress in the development of breast cancer and prostate cancer: a prospective cohort study of employed males and females with 30 years of follow-up. Eur J Cancer 43:1060–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.027

Holmes TH, Rahe RH (1967) The social readjustment rating scale. J Psychosom Res 11:213–218

Gidron Y, Fabre B, Grosman H et al (2011) Life events, cortisol and levels of prostate specific antigen: a story of synergism. Psychoneuroendocrinology 36:874–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.11.011

Nicolson NA (2008) Measurement of cortisol. Handb Physiol Res Methods Health Psychol 1:37–74

Thoits PA (2010) Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 51:S41–S53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383499

Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, Williams DR (2011) Racial disparities in health: the impact of multi-dimensional measures of race/ethnicity on the self-reported health status of Latinos. Bois Rev Soc Sci Res Race 8:95–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000087

Ong AD, Fuller-Rowell T, Burrow AL (2009) Racial discrimination and the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol 96:1259

Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L (2009) Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 135:531

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2009) Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med 32:20–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0

Lee DB, Peckins MK, Heinze JE et al (2018) Psychological pathways from racial discrimination to cortisol in African American males and females. J Behav Med 41:208–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-017-9887-2

Ong AD, Williams DR, Nwizu U, Gruenewald TL (2017) Everyday unfair treatment and multisystem biological dysregulation in African American adults. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol 23:27–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000087

Korous KM, Causadias JM, Casper DM (2017) Racial discrimination and cortisol output: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med 193:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.09.042

Agunwamba AA, Kawachi I, Williams DR et al (2017) Mental health, racial discrimination, and tobacco use differences across rural-urban California. J Rural Health 33:180–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12182

Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD (2005) Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:607–628. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJM, Miller SB (2014) Perceived racial discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol 33:20–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033718

James SA (1994) John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult Med Psychiatry 18:163–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01379448

James SA, Strogatz DS, Wing SB, Ramsey DL (1987) Socioeconomic status, John Henryism, and hypertension in Blacks and Whites. Am J Epidemiol 126:664–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114706

James SA, Van Hoewyk J, Belli RF et al (2006) Life-course socioeconomic position and hypertension in African American men: the Pitt County Study. Am J Public Health 96:812–817. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.076158

Bennett GG, Merritt MM, Sollers JJ III et al (2004) Stress, coping, and health outcomes among African-Americans: a review of the John Henryism hypothesis. Psychol Health 19:369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/0887044042000193505

Coker AL, Sanderson M, Ellison GL, Fadden MK (2006) Stress, coping, social support, and prostate cancer risk among older African American and Caucasian men. Ethn Dis 16:978–987

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1994) Perceived stress scale. Mind Garden Inc., Menlo Park

Butow PN, Hiller JE, Price MA et al (2000) Epidemiological evidence for a relationship between life events, coping style, and personality factors in the development of breast cancer. J Psychosom Res 49:169–181

White VM, English DR, Coates H et al (2007) Is cancer risk associated with anger control and negative affect? Findings from a prospective cohort study. Psychosom Med 69:667–674. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31814d4e6a

Boylan JM, Lewis TT, Coe CL, Ryff CD (2015) Educational status, anger, and inflammation in the MIDUS national sample: does race matter? Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med 49:570–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9687-2

Chapman BP, Fiscella K, Kawachi I et al (2013) Emotion Suppression and mortality risk over a 12-year follow-up. J Psychosom Res 75:381–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.07.014

Consedine NS, Magai C, Horton D (2005) Ethnic Variation in the impact of emotion and emotion regulation on health: a replication and extension. J Gerontol Ser B 60:P165–P173. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/60.4.P165

Blaes A, Prizment A, Koene RJ, Konety S (2017) Cardio-oncology related to heart failure common risk factors between cancer and cardiovascular disease. Heart Fail Clin 13:367–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hfc.2016.12.006

Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, Konety SH (2016) Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation 133:1104–1114. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406

Boehm JK, Kubzansky LD (2012) The heart’s content: the association between positive psychological well-being and cardiovascular health. Psychol Bull 138:655–691. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027448

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Boehm JK, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky LD (2014) Taking the tension out of hypertension: a prospective study of psychological well being and hypertension. J Hypertens 32:1222–1228. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000175

Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, Blane DB (2003) A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment Health 7:186–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786031000101157

Okely JA, Gale CR (2016) Well-being and chronic disease incidence: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosom Med 78:335–344. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000279

Feller S, Teucher B, Kaaks R et al (2013) Life satisfaction and risk of chronic diseases in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC)—Germany study. PLoS ONE 8:e73462. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073462

Van Cappellen P, Rice EL, Catalino LI, Fredrickson BL (2018) Positive affective processes underlie positive health behaviour change. Psychol Health 33:77–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1320798

Boehm JK, Chen Y, Williams DR et al (2015) Unequally distributed psychological assets: are there social disparities in optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect? PLoS ONE 10:e0118066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118066

Krueger PM, Saint Onge JM, Chang VW (2011) Race/ethnic differences in adult mortality: the role of perceived stress and health behaviors. Soc Sci Med 73:1312–1322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.007

Adam TC, Epel ES (2007) Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav 91:449–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011

Aubin H-J, Rollema H, Svensson TH, Winterer G (2012) Smoking, quitting, and psychiatric disease: a review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36:271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.06.007

Brumpton B, Langhammer A, Romundstad P et al (2013) The associations of anxiety and depression symptoms with weight change and incident obesity: the HUNT study. Int J Obes 37:1268

Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Tworoger SS, Poole EM et al (2016) Prospective changes in healthy lifestyle among midlife women: when psychological symptoms get in the way. Am J Prev Med 51:327–335

Lavalette C, Trétarre B, Rebillard X et al (2018) Abdominal obesity and prostate cancer risk: epidemiological evidence from the EPICAP study. Oncotarget 9:34485–34494. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.26128

Giovannucci E, Leitzmann M, Spiegelman D et al (1998) A prospective study of physical activity and prostate cancer in male health professionals. Cancer Res 58:5117–5122

Torti DC, Matheson GO (2004) Exercise and prostate cancer. Sports Med Auckl NZ 34:363–369

Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Platz EA et al (2007) Risk factors for prostate cancer incidence and progression in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer 121:1571–1578. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.22788

Aune D, Rosenblatt DAN, Chan DS et al (2015) Dairy products, calcium, and prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr AJCN. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.067157

Huncharek M, Haddock KS, Reid R, Kupelnick B (2010) Smoking as a risk factor for prostate cancer: a meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies. Am J Public Health 100:693–701. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.150508

Zamora D, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR, Popkin BM (2010) Diet quality and weight gain among black and white young adults: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study (1985–2005). Am J Clin Nutr 92:784–793. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29161

Song M, Giovannucci E (2016) Preventable incidence and mortality of carcinoma associated with lifestyle factors among whites in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2:1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0843

Mordukhovich I, Reiter PL, Backes DM et al (2011) A review of African American-white differences in risk factors for cancer: prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control CCC 22:341–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-010-9712-5

Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA (2010) Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health 100:933–939. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446

Williams DR, Mohammed SA (2013) Racism and health I: pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci 57:1152–1173. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213487340

Black PH, Garbutt LD (2002) Stress, inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Psychosom Res 52:1–23

Spruill TM (2010) Chronic psychosocial stress and hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 12:10–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-009-0084-8

Krishnan V, Nestler EJ (2010) Linking molecules to mood: new insight into the biology of depression. Am J Psychiatry 167:1305–1320. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.10030434

Reiche EMV, Nunes SOV, Morimoto HK (2004) Stress, depression, the immune system, and cancer. Lancet Oncol 5:617–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01597-9

Segerstrom SC, Miller GE (2004) Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 130:601–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601

Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH (2001) Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:4770–4775. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.081072698

Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J (2006) “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health 96:826–833. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749

Upchurch DM, Stein J, Greendale GA et al (2015) A longitudinal investigation of race, socioeconomic status, and psychosocial mediators of allostatic load in midlife women: findings from the study of women’s health across the nation. Psychosom Med 77:402–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000175

Danese A, McEwen BS (2012) Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav 106:29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

Crimmins EM, Kim JK, Alley DE et al (2007) Hispanic paradox in biological risk profiles. Am J Public Health 97:1305–1310. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.091892

Carlson E, Chamberlain R (2005) Allostatic load and health disparities: a theoretical orientation. Res Nurs Health 28:306–315

Borrell LN, Dallo FJ, Nguyen N (2010) Racial/ethnic disparities in all-cause mortality in U.S. adults: the effect of allostatic load. Public Health Rep 125:810–816. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335491012500608

Puterman E, Gemmill A, Karasek D et al (2016) Lifespan adversity and later adulthood telomere length in the nationally representative US Health and Retirement Study. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:E6335–E6342. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1525602113

Garad Y, Maximova K, MacKinnon N et al (2017) Sex-specific differences in the association between childhood adversity and cardiovascular disease in adulthood: evidence from a national cohort study. Can J Cardiol 33:1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2017.05.008

Kananen L, Surakka I, Pirkola S et al (2010) Childhood adversities are associated with shorter telomere length at adult age both in individuals with an anxiety disorder and controls. PLoS ONE 5:e10826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010826

Pearlin LI, Schieman S, Fazio EM, Meersman SC (2005) Stress, health, and the life course: some conceptual perspectives. J Health Soc Behav 46:205–219

Umberson D, Williams K, Thomas PA et al (2014) Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: childhood adversity, social relationships, and health. J Health Soc Behav 55:20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146514521426

Kelly-Irving M, Lepage B, Dedieu D et al (2013) Childhood adversity as a risk for cancer: findings from the 1958 British birth cohort study. BMC Public Health 13:767. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-767

Sutcliffe S, Colditz GA (2013) Prostate cancer: is it time to expand the research focus to early-life exposures? Nat Rev Cancer 13:208–518. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3434

Chornokur G, Dalton K, Borysova M, Kumar N (2011) Disparities at presentation, diagnosis, treatment and survival in African American men, affected by prostate cancer. Prostate 71:985–997. https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.21314

DeLancey JOL, Thun MJ, Jemal A, Ward EM (2008) Recent trends in Black-White disparities in cancer mortality. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res Cosponsored Am Soc Prev Oncol 17:2908–2912. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0131

Hackshaw-McGeagh LE, Perry RE, Leach VA et al (2015) A systematic review of dietary, nutritional, and physical activity interventions for the prevention of prostate cancer progression and mortality. Cancer Causes Control CCC 26:1521–1550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0659-4

Menichetti J, Villa S, Magnani T et al (2016) Lifestyle interventions to improve the quality of life of men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 108:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.10.007

Hiza HAB, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA, Sex R, Ethnicity (2013) Diet quality of Americans differs by age. Income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet 113:297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.011

August KJ, Sorkin DH (2011) Racial/ethnic disparities in exercise and dietary behaviors of middle-aged and older adults. J Gen Intern Med 26:245–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1514-7

Lopez RP, Hynes HP (2006) Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: public health research needs. Environ Health 5:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-5-25

Pedersen VH, Armes J, Ream E (2012) Perceptions of prostate cancer in Black African and Black Caribbean men: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology 21:457–468. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2043

Woods VD, Montgomery SB, Belliard JC et al (2004) Culture, Black men, and prostate cancer: what is reality? Cancer Control J Moffitt Cancer Cent 11:388–396

Price JH, Colvin TL, Smith D (1993) Prostate cancer: perceptions of African-American males. J Natl Med Assoc 85:941–947

Magnus M (2004) Prostate cancer knowledge among multiethnic black men. J Natl Med Assoc 96:650–656

Ogunsanya ME, Brown CM, Odedina FT et al (2017) Knowledge of prostate cancer and screening among young multiethnic black men. Am J Mens Health 11:1008–1018

Allen JD, Kennedy M, Wilson-Glover A, Gilligan TD (2007) African-American men’s perceptions about prostate cancer: implications for designing educational interventions. Soc Sci Med 64:2189–2200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.007

Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N et al (2015) Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10:e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the National Institute of Health 3R25CA057711. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. CTF received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé. The development of the manuscript was partially supported by Cancer Disparities Research Network/Geographic Management Program (GMaP) Region 4 funded by 3 P30 CA006927-52S2 and CTSI Mentored Career Development Award (KL2 TR002545).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cuevas, A.G., Trudel-Fitzgerald, C., Cofie, L. et al. Placing prostate cancer disparities within a psychosocial context: challenges and opportunities for future research. Cancer Causes Control 30, 443–456 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01159-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01159-1