Abstract

Contemporary leaders are increasingly challenged to execute their leadership roles with a higher sense of responsibility. However, only a handful of studies have empirically examined the influence of responsible leadership on employee and organisational outcomes. Using Social Identity Theory and Psychological Contract Theory, this paper reports the findings of the relationship between responsible leadership and organisational commitment through the mediating role of employee turnover intentions. A web-based online survey was administered to collect data targeting a sample of 200 Australian employees working full time. Structural equation modelling was used to analyse the data. The results reveal that perceived responsible leadership significantly influences employees’ organisational commitment and their turnover intentions. Moreover, the direct relationship between responsible leadership and organisational commitment was found to be partially mediated by employees’ turnover intentions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion of responsible leadership (RL) has garnered increased attention in various fields of organisational study. It has become part of numerous conceptualisations as to what it means to be a responsible leader (Waldman 2014; Antunes and Franco 2016). Recent corporate scandals and ethical lapses have prompted questioning of our basic thoughts about organisations’ management and the role of RL (Fernando 2016; Stahl and Luque 2014; Fernando and Sim 2011). Corporate collapses (Enron, HIH and WorldCom), product recalls (Volkswagen and Toyota), and corporate excesses (Exxon-Valdez) have called into question the responsibility of managerial leadership. Waldman and Galvin (2008) suggested that the notion of responsibility is missing from established leadership descriptors such as transformational, charismatic, authentic, participative, servant, shared or even spiritual and ethical leadership. Similarly, there are increasing demands on leaders to lead in a way that is responsible towards not only the business organisation, but its broader stakeholders. Maak and Pless (2006) define RL as the process that leads to building and sustaining positive relationships with both internal and external stakeholders to the organisation. Therefore, RL has emerged as an essential management discourse, and appeals have grown louder for leaders to act responsibly in a business environment that has lost legitimacy and trust (Maak and Pless 2006; Antunes and Franco 2016; Miska and Mendenhall 2015; Maak et al. 2016). The early stages of RL development focused more on conceptualising and exploring individuals’ values and ethical motivations. At present, RL scholars employ less subjective and normative assumptions and focus on leadership orientations and capabilities rather than virtues (Miska and Mendenhall 2015). Few studies have empirically examined the influence of RL on employee and organisational outcomes.

Organisational commitment is a key employee outcome that leads employees to perform effectively. The significance of organisational commitment has been well acknowledged in leadership studies (Voegtlin et al. 2012; Miska and Mendenhall 2015). To ensure employee commitment requires effective leadership (Gardner 1990). An extensive body of the literature is concerned with the interrelations between leaders and the workgroup, particularly regarding how various leadership styles are related to the level of organisational commitment (Meyer et al. 2002). It is argued that the behaviours of managerial leadership determine how leaders establish direction, align people, and motivate as well as inspire organisational members (Kotter 1990). In other words, appropriate leadership fosters a high-commitment environment. Hence, studies on various leadership styles as well as employees’ organisational commitment have argued that leadership responses drive follower commitment (Kim and Brymer 2011; Cerit 2010). The current challenge in leadership concerns the capacity to create conditions in organisations that influence employees to show higher organisational commitment. Several researchers have suggested that RL has a positive influence on employee’s organisational commitment (Voegtlin et al. 2012; Doh and Quigley 2014; Miska and Mendenhall 2015). They also suggest that due to a broad range of stakeholders inside and outside of the organisation, that RL can have a positive influence on organisational commitment.

But does the relation of leadership and organisational commitment remain the same when employees hide their turnover intentions? Desirable responsible action by leaders that meaningfully addresses stakeholder needs can help elevate the organisational commitment level of followers who expect such responsible behaviour from their leaders (Doh and Quigley 2014; Miska and Mendenhall 2015). These followers are likely to have increased attachments and attraction to such leaders and their organisations. Such attachments and attractions would reduce employee uncertainty about their work role and help increase positive attitudes towards their work roles (Voegtlin et al. 2012; Doh and Quigley 2014). In such circumstances, leading responsibly is likely to reduce turnover intentions leading to among others, increased organisational commitment and employee cost–benefits to the organisation. Hence, examining the relationship of RL with organisational commitment may provide useful insights regarding employees’ turnover intentions when turnover intention is introduced as a mediational influence. We follow recent organisational studies where turnover intention was examined as an antecedent of employees’ behavioural outcomes (Christian and Ellis 2014; Brien et al. 2015). The justification for such an approach is explained later in the hypothesis development section. Therefore, in this study we propose and examine RL as an antecedent to the three components of employees’ organisational commitment (affective, continuance, and normative commitment), and the mediating effect of turnover intentions on the relationship between RL and organisational commitment.

Industry reports, including some from Australia, show that about one in eight workers, or approximately 180 million employees in 142 countries, is psychologically committed to their jobs and likely to be making positive contributions to their organisations (Gallup 2009). Over the last two decades, studies on how leadership can improve organisational outcomes have steadily increased, but only a few have examined the role of RL in organisational practice. Currently, even more limited research exists concerning RL and employees’ work-related outcomes, despite the suggestion that RL can affect organisations more than other forms of leadership. Hence, the findings of the relationships proposed in this paper should address some of these concerns by providing guidelines for designing work contexts to promote RL, lower employee turnover intentions and increase employee organisational commitment.

Thus, the aim of this paper is to report the findings of a study testing the relationship between employees’ perceptions about their managers’ RL responses and organisational commitment. In addition, this paper reports the influence of employee turnover intentions as a mediator. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. ‘Literature Review’ section discusses the relevant literature on RL, organisational commitment and employee turnover intentions. ‘Hypotheses Development’ section presents the development of hypotheses explaining how RL influences organisational commitment directly as well as mediating through employees’ turnover intentions. ‘Methods’ and ‘Results and Hypotheses Testing’ sections give an overview of the methodological approach and present the empirical results from Australia. ‘Discussion’ and ‘Conclusion’ sections provide a discussion of the main findings, followed by study implications, limitations and research avenues, and conclusions.

Literature Review

Responsible Leadership (RL)

The concept of RL is primarily founded on stakeholder theory (Freeman et al. 2007; Antunes and Franco 2016) and operationalised from the perspective of employees and their views of leaders’ actions to organisational value creation (Doh et al. 2011; Miska and Mendenhall 2015). Currently, several scholars (Waldman and Balven 2014; Witt and Stahl 2016; Maak et al. 2016) have discussed how RL as an essentially normative leadership approach is distinct from other values-centred leadership theories like ethical leadership (Brown and Trevino 2006), servant leadership (Greenleaf 2002), authentic leadership (Gardner et al. 2005), and transformational leadership (Bass and Avolio 1994). According to Maak et al. (2016), the key difference between the values-centred leadership and RL is the latter’s focus on sustainable value creation through positive social change. Hence, RL can be understood from a relational and ethical dimension (Miska and Mendenhall 2015; Maak et al. 2016). Scholars have suggested that the study of RL needs to consider organisational perspectives in terms of both antecedents (Stahl and Luque 2014) and employee outcomes (Voegtlin et al. 2012; Miska and Mendenhall 2015).

The notion of RL has been conceptualised as an emerging concept at the intersection between studies in ethics, leadership, and corporate social responsibility (Waldman and Siegel 2008; Maak et al. 2016; Miska and Mendenhall 2015). Maak and Pless (2006, p. 103) defined RL as ‘a relational and ethical phenomenon, which occurs in social processes of interaction with those who affect or are affected by leadership and have a stake in the purpose and vision of the leadership relationship’. RL is considered to have a broader appeal than ethical leadership theories. RL is a process model of leadership which is not directly linked to the ethical characteristics of the leaders. Such an interpretation (e.g. good virtues) in a global setting could pose several limitations (Voegtlin et al. 2012, p. 5). These authors therefore conceptualise ethical characteristics as the antecedents of leading responsibly. From a broader perspective, RL represents a concept that exists at the intersections of two existing fields of study: social responsibility and leadership (Waldman and Balven 2014; Antunes and Franco 2016). According to Waldman and Balven (2014), social responsibility has been a focus of many studies, such as its relationship to firm financial performance (Orlitzky et al. 2003). However, little is known about how leader actions and decisions affect or are affected by social responsibility. Doh et al. (2011) had examined how human resource practices, stakeholder culture, and managerial support can influence employee perceptions of RL. The current study focuses on RL from an individual perspective and examines employees’ perceptions about their managers’ RL responses and the effect of these perceptions on employee turnover intentions and organisational commitment.

Organisational Commitment

Organisational commitment is a multidimensional construct that can take different forms (e.g. Meyer and Allen 1991a). It can be directed at different targets, or foci, including organisations, work teams, projects, and goals (e.g. Becker 1992). This study focuses on employee commitment to the organisation (i.e. organisational commitment) because it has been studied most extensively, particularly within the context of leadership (Jackson et al. 2013) but not with RL.

Organisational commitment is regularly conceptualised as an affective attachment to an organisation. Accordingly, this affective attachment leads an individual to share organisation’s values and increases the desire to remain in the organisation and the willingness to exert more effort (Mowday et al. 1979). Researchers have found that organisational commitment is a function of several variables such as job satisfaction, motivation, decision-making, organisational support, reward, communication, and leadership styles (Salami and Omole 2005).

Organisational commitment is known to comprise of three components: affective (product of emotional attachments), continuance (the costs of leaving, such as losing attractive benefits or seniority), and normative commitment (individual’s personal values) (Meyer et al. 1993; Brief (1998). According to Hartman (2000), among others, feelings of belonging and sense of attachment to the organisation project affective commitment. It is related to employees’ attachment and identification with the organisation (Meyer et al. 1993). According to Dawley et al. (2005), affective commitment makes employees maintain their organisational membership.

As the name suggests, continuance commitment is about the pros and cons for employees on the costs associated with staying or leaving in the organisation. If they perceive that the costs of staying are lesser than the costs of leaving, they will continue to work for the organisation. According to Murray et al. (1991), employees decide to continue with organisation because of the fear of failing to find another job and loss of benefits. The third component of organisational commitment refers to normative commitment which is about the pressure that employee’s feel to remain with the organisation. According to Meyer and Allen (1991a), feelings of obligation compel employees to stay with an organisation.

Committed employees perform better (Larson and Fukami 1984), and organisational commitment has been considered as an antecedent to many organisational outcomes (Meyer and Allen 1997; Meyer et al. 2002). For example, organisational commitment has been found to affect performance, absenteeism, attendance, and turnover (Mathieu and Zajac 1990). There is a significant body of the literature that suggests a link between leadership styles to organisational commitment. Several researchers such as Bass et al. (2004), Bass and Avolio (1990), and Stogdill (1963) have demonstrated positive relationships between numerous leadership styles and employee attitudes, motivation, and performance, all of which can affect organisational commitment levels.

Employee Turnover Intention

Considered as employees’ withdrawn behaviour (still at work but not engaged), employee turnover intention is a precursor to turnover itself. Employee turnover intention is defined as individuals’ withdrawal from their occupation or organisation, and actively searching for other jobs or career alternatives (Blau 2007). The concept of employee turnover intention has been studied by researchers in various disciplines and through attitudinal, behavioural, and organisational factors (Samad 2006). For example, work-related issues (managerial leadership or organisational commitment), personal issues (health conditions or illness), external factors (social impressions about the organisation), and job-related factors (job environment) play an important role in employees’ decision to remain or leave the organisation. Moreover, employees’ demographic variables such as age and tenure have been found to be significant to employee turnover intention (Cohen 1993). Bernat (2007) referred to the reduction in employee turnover as a financial deliverance for organisations, and organisations spend millions of dollars in building their human capital while dealing with employee turnover issues. Myatt (2008) noted that employees leave their jobs for several reasons, most of which have direct or indirect relationships with various leadership styles. Therefore, researchers are now very much concerned about the direct role leadership plays in employee turnover. In line with recent studies using employee turnover intentions as an antecedent (Christian and Ellis 2014; Brien et al. 2015), in this study, we use it as an antecedent of organisational commitment.

Hypotheses Development

Responsible Leadership and Organisational Commitment

Little is known about the relationship between the newly evolved notion of RL and employee outcomes such as employee commitment. However, various leadership approaches have been investigated for their influence on employees’ organisational commitment. These include studies on servant leadership (e.g. Liden et al. 2014), authentic leadership (e.g. Hirst et al. 2016), ethical leadership (e.g. Bedi et al. 2016), and transformational leadership (e.g. Ng 2016). RL as a social-relational process considers employees as a primary stakeholder of a responsible organisation. Given the centrality of social-relational processes in the conceptualisation of RL, we use social identity theory (SIT) to explain the link between RL and employee commitment.

SIT (Tajfel 1974; Tajfel and Turner 1986) explains the relationship between an individual and the group and clarifies how people identify themselves and behave in relation to the group. SIT has been used in various settings including psychology (e.g. Turner 1999; Tajfel and Turner 1986), management (e.g. Tran et al. 2011; Kfirat et al. 2016), and to explain relationships between groups (e.g. Tajfel and Turner 2004; Turner 2010). SIT suggests that people’s self-image consists of an individual and a group component. It is defined as ‘that part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership of a social group (or groups) together with the emotional significance attached to that membership’ (Tajfel 1974, p. 69, sic.). The notion of SIT further suggests that people strive to attain a positive social identity and enhance their self-esteem and that this positive identity derives largely from constructive comparisons made between own and other groups (Tajfel and Turner 2004). This theory has been empirically validated in leadership studies as the social identity theory of leadership, recognising leadership as a group process that develops from the social classification and depersonalisation processes linked with social identity (Hogg 2001).

In a leadership context, SIT would be useful to understand when and why a follower likes the leader and his/her organisation. In a stakeholder culture where employees are a primary stakeholder (Doh et al. 2011), by aligning themselves to a likeable leader and organisation, employees can derive meaning and identity. For example, Doh et al. (2011) proposed how a positive stakeholder culture promoted by legitimacy-enhancing activities like corporate social responsibility initiatives could translate into attracting followers to the leader and organisation. When followers are attracted to the leader and organisation, the influencing process that is at the heart of the leadership process can be enacted easily. Responsible leadership practice can attract followers who are also responsible. Because RL is about engaging all stakeholders both internal and external, RL practice can help create a positive stakeholder culture. Because of the alignment of personal and organisational values, these followers are more likely to be committed to their organisations. Following SIT, followers’ attraction to a leader and organisation is likely to increase the feelings of belonging and sense of attachment to the organisation. Responsible leaders as role models can increase the affective commitment of their followers because it is likely to increase their attachment and identification with the organisation. Employees working for leaders that demonstrate responsibility are more likely to be aligned with such a positive stakeholder culture (Doh et al. 2011), its values and as a result, willingness to maintain their organisational membership (Dawley et al. 2005). Accordingly, we hypothesise the following:

H 1

There is a positive relationship between perceived RL and organisational commitment.

Responsible Leadership and Employee Turnover Intention

Researchers indicate that employees respond positively to leaders’ behaviour that is predominantly employee-oriented. Leaders’ pro-employee behaviours also influence employees’ turnover intentions (Jaramillo et al. 2009). The relationship between various value-based leadership approaches such as transformational (e.g. Bass et al. 2004), ethical (e.g. Brown and Trevino 2006), authentic (e.g. Hirst et al. 2016), and servant leadership on employee turnover intentions has been studied. The common thread across the findings in these studies is how leaders engage and motivate followers to such an extent that there is little or no room for the manifestation of turnover intentions.

Employee turnover intentions may arise because of several reasons; for example, low salaries, work overload, relocation, layoffs, and job dissatisfaction (Schwerin and Kline 2008). These intentions frequently end with actual turnovers. Mobley (1977) modelled how employees’ satisfaction affected their turnover and arrived at the conclusion that dissatisfaction with the job or leadership affects thoughts of staying or leaving. Similarly, Griffith (2004) indicated that the relationship between leadership and turnover is best described through job satisfaction with the work environment, including satisfaction with the leader. Hence, if employees have a high-quality relationship with their leaders and are satisfied with them, leaving the organisation would entail psychological loss, making withdrawal costly for both employees and employers (Mossholder et al. 2005).

Applying SIT, a responsible leader can engage followers by demonstrating responsible action with all stakeholders. By aligning with a responsible approach to leadership, followers are able to gain membership to the ‘in’ group (e.g. Waldman and Galvin 2008), thus increasing the loyalty and attachment to the responsible leader and the organisation. Increased engagement and feelings of attachment and belonging to the ‘in’ group of the leadership circle are likely to reduce any employee turnover intentions. Accordingly, we hypothesise as follows:

H 2a

There is a negative relationship between perceived RL and employee turnover intentions.

Employees’ Turnover Intention and Organisational Commitment

The concept of employee turnover intention is not the same as actual turnover, but is often used as a surrogate (Locke et al. 1970; Fakunmoju and Kersting 2016). This is because the intention to leave is considered to be the immediate precursor to leaving the organisation. The literature largely consists of studies examining commitment as an antecedent of turnover intentions. These studies have found a negative relationship between organisational commitment and employee turnover (Jung and Kim 2012; Lee et al. 2012; Meyer and Allen 1991a; Meyer and Allen 1997; Sahi and Mahajan 2014; Faloye 2014). However, employee turnover intentions have received attention in recent organisational studies as an antecedent of employees’ behavioural outcomes, such as leadership outcomes, employee well-being, perceived organisation support, and organisation commitment (Christian and Ellis 2014; Brien et al. 2015). Noting that our study is about RL which is based on promoting relations with internal and external stakeholders, an effective responsible leader is expected to engage and motivate followers through a relational approach (Maak and Pless 2006). Given the role played by psychological attachment/detachment in influencing employees’ turnover intentions to manifest into actual turnover, we use psychological contract (Rousseau 1995) to explain this use of employee turnover intentions as an antecedent of organisational commitment.

The role of turnover intentions on the level of commitment to the organisation can be significant as turnover intentions will negatively impact the relational aspects of the psychological contract (Rousseau 1995). Psychological contract refers to ‘employees’ perceptions of what they owe to their employers and what their employers owe to them’ (Robinson 1996, p. 574). There are two elements in these contracts, transactional (e.g. pay and benefits) and relational (e.g. career advancement opportunities, training and development) components (Christian and Ellis 2014). According to Christian and Ellis (2014), relational contracts promote employees to envision a long-term future with an employer, and that they will gain from such a relationship (Robinson and Rousseau 1994). As a result, they experience feelings of loyalty (Robinson et al. 1994). Employees with intentions to leave are likely to psychologically detach themselves from these relational components. Turnover intentions could be entertained by employees without the knowledge of the organisation; hence, even though organisations continue to maintain superior human resource practices to reward and develop employees for a long-term relationship, employees wanting to exit could have already psychologically withdrawn from the organisation (Burris et al. 2008). The weak psychological contract results in the lack of commitment and withdrawal behaviours that frequently follow turnover intentions (Christian and Ellis 2014; Griffith 2004; Mobley 1977). Similar to these studies, in a responsible leadership context where the relational element is central, we are concerned about how turnover intentions influence the relationship between employees and their leader and the organisation, shown through their organisational commitment level. Accordingly, we hypothesise as follows:

H 2b

There is a negative relationship between employees’ turnover intentions and organisational commitment.

As noted earlier, employee turnover intention has received increasing attention in recent organisational studies as an antecedent of employees’ behavioural outcomes (Christian and Ellis 2014; Brien et al. 2015). RL is primarily driven through a relational approach (Maak and Pless 2006). As explained in our justification for H2a, when employees are aligned with the actions of a responsible leader, they are likely to have a strong attachment and attraction to the leader and organisation. According to SIT (Tajfel 1974; Tajfel and Turner 1986), employees identify themselves and behave in relation to the group. A responsible leader who can create a positive stakeholder culture can attract employees who uphold responsible values. Belonging to such an organisation would define who they are and work will be more meaningful to them. Under these conditions, there is little room for developing intentions to leave. On the other hand, when the employees have a weak alignment with the actions of a leader and the organisation, they will be less attached and attracted to the leader and organisation. These conditions can lead to manifestation of thoughts of quitting.

Furthermore, as explained in our justification for H2b, in a responsible leadership context, employee turnover intentions can change the relational elements between employees and their organisation and lead to changes in commitment levels. A strong psychological contract (Rousseau 1995) between the employee and the organisation would mean that employees’ perceive that the leader and the organisation values their contributions to organisational goals, and accordingly employees will increase their effort and commitment levels (Rhoades and Eisenberger 2002; Ng and Sorensen 2008). On the other hand, employees with turnover intentions gradually become psychologically detached which can lead to lower commitment levels and disengagement at work (Joinson 2000; Taifor et al. 2011).

Given the above relationships, the question arises as to whether employee turnover intention mediates the relationship between perceived RL and organisational commitment. Employees who are highly influenced by responsible leaders would turn up to work despite having turnover intentions and may show higher organisational commitment. However, employees’ turnover intentions may have some relationship with organisational commitment entirely independent of the RL effect. Thus, the above warrants an investigation to determine whether employee turnover intention mediates the relationship between RL and organisational commitment. Accordingly, we hypothesise as follows:

H 3

Employees’ turnover intention mediates the association between RL and organisational commitment.

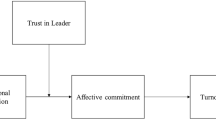

From the above discussions, a hypothesised model for this study is depicted in Fig. 1.

Methods

Sample and Procedures for Data Collection

Through a professional survey company based in the USA, a total of 3500 email invitations were sent out with a request to complete a web-based questionnaire. The participants included a sample of full-time employees working for a supervisor in various Australian industry sectors. To exclude other types of employees with different views and attitudes towards the study variables, only full-time employees were selected for the study. The targeted sample size of this study was 200, as in similar studies (Nyberg et al. 2008; Gilbreath and Karimi 2012). In addition, a power analysis was conducted with an effect size of .15 and an error probability of .05, and a size of at least 200 was deemed sufficient. However, a web-based survey provides no chance to derive a sample based on any explicit selection procedure. Hence, the probability of any participant being selected was unknown, and a non-probability judgemental sampling was used to select potential participants from the target population. Burns and Bush (2006) had suggested that judgemental sampling is considered to constitute an ‘expert’, ‘educated guess’ to represent any target population. Finally, a total of 323 responses were collected, from which were taken the 200 survey responses for the final data analysis. However, 123 incomplete surveys were removed, resulting in an overall response rate of 9.2%. The participants’ responses were anonymous, and every step was taken to ensure the privacy of the participants. In addition, participants had the freedom to discontinue their participation at any point of the survey.

In the demographic profile, 52.5% of the survey respondents were women and 47.5% were men. The age of respondents ranged from 18 to 66 or above, with a highest being 34% for 26–35 years. Among all respondents, 28.5% completed their bachelor degrees, and 32% had 4–5 years of work experience. Lastly, respondents identified themselves as representing various sectors of the Australian workforce with 15% from the financial sector, 4% from the telecommunication sector, 11% from the health sector, and 65% from other sectors.

Measures

In this study, RL was measured using the scale from Doh et al. (2011). This scale had a total of 13 items to operationalise RL from the employees’ perspective and their views of managers’ actions. The Doh et al. (2011) scale comprises of three subscales: stakeholder culture (e.g. this organisation takes an active role in its community), HR practices (e.g. our organisation’s programme for high potentials helps in talent retention), and managerial support (e.g. my immediate manager leads by example). Participants responded using a seven-point Likert scale (1 being ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 being ‘strongly agree’). However, the questionnaire was simplified with some alternative or synonymous words based on pilot test responses to improve participants’ comprehension. In this study, the reliability score (Cronbach’s alpha) of perceived RL was .94 with all three components as a composite scale. However, the components of stakeholder culture, HR practices, and managerial support had α value of .87, .93, and .95, respectively.

Organisational commitment was measured using the three commitment scales adapted from Meyer et al. (1993). This scale had three subscales: affective, continuance, and normative. The questionnaire contained 18 questions (e.g. I do not feel emotionally attached to this organisation). Participants responded using a five-point scale (1 being ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 being ‘strongly agree’). Ko et al. (1997) conducted a study using Meyer et al.’s (1993) scales and reported coefficient alphas of .86, .58, and .78 for affective, continuance, and normative commitment in sample 1 and .87, .64, and .76, respectively, in sample 2. However, in this study, the reliability score (Cronbach’s alpha) of organisational commitment was .88 with all three components as a composite scale, and the components of affective, continuance, and normative commitment had α values of .86, .73, and .90, respectively.

Employees’ turnover intention was measured with the scale developed by Donnelly and Ivancevich (1975). The three-item scale used a five-point Likert scale (1 being ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 being ‘strongly agree’). A sample from the scale was ‘I often think of quitting my current job’. Donnelly and Ivancevich (1975) provided evidence of the scale’s criterion validity, and the reliability of the scale was indicated with a Cronbach’s alpha of .88 (Fournier et al. 2010). However, the reliability score (Cronbach’s alpha) of employee turnover intentions in this study was .90.

For the demographic profile, respondents provided information on gender, age, marital status, personal income, academic background, duration of service at work, hours worked per week, the industry they presently work, and the duration of service under the reporting supervisor or manager at the time of data collection.

Data Analysis Procedures

This study used structural equation modelling (SEM) to conduct the data analysis. SEM is a feasible statistical tool for exploring the multivariate relationships among some or all of the variables, and it provides a comprehensive approach to a research question for measuring and analysing theoretical models (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). In this study, the two-step process for SEM techniques (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) was used to test the hypothesised model. The first step tests the reliability, factor loading, and goodness of fit for each scale of the study. An SEM measurement model was used to estimate the composite scale reliabilities and discriminant validities of the latent variables. This was achieved by comparing the correlations between variables. Unequal correlations establish discriminant validity. Also, Cronbach’s alphas were calculated to determine whether the instruments maintained reasonable (>.78) internal consistency (reliability). The second step, the structural model stage, focused on the overall relationship between constructs by outlining the details on how each construct appears in the model. Here, SEM involved an evaluation of a structural model using path analysis (Byrne 2010). For this study, the structural model specified that relationships exist among the variables as follows: (a) a direct effect of RL on organisational commitment, (c) a direct effect of RL on employee turnover intentions, and (f) a direct effect of employee turnover intentions on organisational commitment. Here, employee turnover intentions were hypothesised as a mediator in the relationship between RL and organisational commitment.

For the data analysis, SEM and factor analysis were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software. The programme established a measurement model for each variable as well as calculated over-fit indices (e.g. Chi-square, root-mean-square error of approximation, norm fit index) and the structural coefficients in the hypothesised model. However, an evaluation of a measurement model using factor analysis alone does not establish causation, and an explanatory relationship by itself was considered an inappropriate method of analysis (Grimm and Yarnold 2000). Path analysis models specify causal relationships, but assume that observed variables are measured without errors. SEM analysis is widely used in path analysis because SEM models take into account ‘the total effect of the explanatory variable on a dependent variable’ (Raykov and Marcoulides 2000). Moreover, SEM considers the direct and indirect effects of one variable on another as well as the measurement errors in observed variables. According to Grimm and Yarnold (2000), the accommodation of unmeasured random error and the evaluation/re-evaluation of score reliability are the greatest attractions of SEM.

This study also considered a mediation effect of employees’ turnover intentions over the relationship of employees’ perceived RL and organisational commitment. To justify this mediating role, a couple of conditions need to be met. First, RL must be related to both employee turnover intentions and organisational commitment, and second, the inclusion of employee turnover intentions into the analysis must reduce the initially observed relationship between RL and organisational commitment. As a general rule, a partially mediated model is supported when the value of indirect effect path (ab) is smaller than the value of total effect path (c) with the same sign. The bootstrapping approach is considered a more valid and powerful method for testing mediation effects. Thus, as per Hayes (2009), it should be the preferred method for mediation analysis. The bootstrapping function in AMOS software is used in SEM due to two reasons. First, it uses number of goodness-of-fit indices to assess whether the hypothesised model fits the observed data to meet the two-step approach of Anderson and Gerbing (1988). Second, rather than testing separate regression analyses, SEM allows testing a mediating hypothesis. According to Byrne (2010), the maximum likelihood estimation method which is used as a default in SEM with AMOS simultaneously calculates all model paths together. SEM differentiates two measurement models, such as reflective and formative (Edwards and Bagozzi 2000). In this study, all the measurements were formative and posit a composite variable that summarises the common variation in a collection of indicators individually. Moreover, in a formative approach, each of the measurements is dependent upon a constructivist, operationalist, or instrumentalist interpretation by the researchers (Coltman et al. 2008).

Results and Hypotheses Testing

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Test

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics, correlation coefficients, and Cronbach’s alpha for all the studied variables.

Here, it can be generalised that based on reference cut-off points for correlation (Cohen 1992), the magnitude of the Pearson correlation coefficient revealed that there is a high correlation between the studied variables. For example, RL is significantly correlated with employees’ organisational commitment and employee turnover intentions, as hypothesised. No weak correlations were found between constructs at the .01 significant levels for this study. Hence, this might be considered as the primary evidence to support the hypotheses of the study.

First Step: Measurement Model

Two steps of SEM (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) were used to test the hypothesised model (Fig. 1). The scale-fit indices and factor loading were applied accordingly. For example, incremental (comparative fit index, Tucker fit index, and normed-fit indices), absolute (Chi-square, χ2/df, p value, goodness-of-fit index, and adjusted goodness-of-fit index), and badness-of-fit indices (standardised root mean residual and root-mean-square error of approximation) were used following the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999) and Byrne (2010).

In this study, RL was measured with 13 items to consider employees’ perceived RL (Doh et al. 2011). This scale corresponds to three subscales: shareholder culture was initially measured by four observed indicators; HR practices were measured by five observed indicators; and managerial support was measured by four indicators. The fit indices showed that RL fitted the data adequately: χ2 = 89.945, χ2/df = 1.836, p = .000, GFI = .94, AGFI = .88, CFI = .98, TLI = .97, NFI = .96, RMSEA = .065 and SRMR = .052. Results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) revealed that the 1 dimensions were significantly loaded on perceived RL (from .60 to .90).

Organisational commitment was measured using the three commitment scales adapted from Meyer et al. (1993). This scale has three subscales: affective, continuance, and normative each of which has 6 items, for a total of 18 items. The second measurement of this study, organisational commitment, corresponded to three subscales: affective, continuance, and normative commitment. The subscales of organisational commitment were measured by six indicators each, and the combined scale fit indicated an adequately acceptable fit: χ2 = 185.98, χ2/df = 1.71, p = .000, GFI = .90, AGFI = .86, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, NFI = .90, RMSEA = .060 and SRMR = .069. Results of the CFA revealed that the 12 factors were significantly loaded onto the overall scale of organisational commitment (from .60 to .86).

The three items were assigned for employees’ leaving intentions to create a single index tapping of employee turnover intentions (Donnelly and Ivancevich 1975). Conducting CFA revealed that the scale for employee turnover intentions (TI) over-fitted, as there were only three items, with GFI = 1, CFI = 1, NFI = 1 and RMSEA = .819 and SRMR = .000. In addition, a composite reliability (Raykov 1997) was measured from the structural model (Fig. 2) with each of their standardised loadings for employee turnover intentions; a reliability score of .88 was found for the scale. The results showed that the three items were significantly loaded onto the TI construct with (from .76 to .95).

Indirect relationship between perceived RL, employee turnover intentions, and organisational commitment. Noten = 200. Bootstrap resample = 5000, percentile and bias-corrected confidence intervals are on 99%. e1–e34: errors terms for indicators, e35 and e36 are residuals for latent variables, RL1–RL13: the 13 items of RL, TI1–TL3: the three items of employee turnover intentions, OC1–OC18: the 14 items of organisational commitment, where OC 10 (−.09), OC 7 (−.06), OC 12 (−.22) and OC 11 (.21) were omitted because of their poor loading (C = 782, ab = .35)

Finally, the loading of items on each construct was valid and above the preferred minimum threshold of acceptability of .39. All values for the loadings were significant at p > .001. Furthermore, each scale had a Cronbach’s alpha above the preferred .88 threshold of acceptability.

Second Step: Structural Model

In this study, the structural model specified the relationships between each of the variables (i.e. RL, employee turnover intentions, and organisational commitment) and indicated the amount of unexplained variance. Parameter estimates from the structural model were used to test the hypotheses. Figure 2 presents the structural model along with the regression weights. Finally, results from the CFA provided evidence that the hypothesised model fitted the data adequately (χ2 = 626, χ2/df = 1.6, GFI = .83, AGFI = .79, RMSEA = .056, SRMR = .060; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; NFI = .88). Therefore, both steps in constructing the structural model have been justified.

Hypotheses Testing

The hypotheses were tested using the parameter estimates from the structural model; it was important to assess whether the collected data violated certain key assumptions within SEM. Hence, multicollinearity and normality were checked in the analysis. The tolerance value and variance inflation factor results confirmed that they were in the appropriate value range without multicollinearity. However, the skewness value was in the range for all constructs (.27 to −.48), indicating a normal distribution.

As shown in Fig. 2, the standardised coefficient for total effect (c) of RL on employee commitment before entering the mediator was significant (β = .782; p < .001). These results mean that hypothesis 1 is fully supported. Furthermore, as Fig. 2 shows, when employee turnover intentions act as a mediator, the influence of RL on commitment remains significant but declines (β = .432; p < .001). Therefore, it hypotheses H2a (β = −.55; p < .001), that there is a significant direct influence of RL on employee turnover intentions, and H2b (β = −.52; p < .001), which state that there is a significant direct influence on employee turnover intentions on employee commitment, are confirmed.

The bootstrapping procedure in AMOS was executed with 5000 resamples on the indirect effects of Hypothesis 3. Bootstrapping is a statistical inference that is based on repeated sampling with replacement from an initially given sample of raw data (Efron and Tibshiriani 1993). As per Hayes (2009), statistical significance for the indirect effect was determined by a 99% bias and accelerated confidence intervals. This shows that employee turnover intentions transmit almost all (β = .35; p < .001) of the influence of RL on organisational commitment, with 99% confidence. Here, the indirect effect of employee turnover intentions is significantly different from zero at p < .001. The total effect of RL on organisational commitment was refined slightly but remained significant when controlling for employee turnover intentions. As predicted, the results support a partial mediation model, and AMOS delivers the squared multiple correlations (R2) for each observed variable rating. Individually, each R2 can be interpreted as the proportion of the total variance in an observed rating that is explained by all variables on which the rating directly depends. Figure 2 shows that a large proportion of the variance in the study variables can be explained. RL explains 31% of the variance in employee turnover intentions, and RL and employee turnover intentions together explain 61% of the variance in organisational commitment.

Table 2 summarises all the results from SEM for the tested hypothesis. As proposed in Hypothesis 1, the direct relationship between RL and organisational commitment was supported. The findings demonstrated that employees who perceive a higher level of RL from their leaders are more likely to be more committed at their work. The results of these hypotheses are in accordance with previous studies conducted using other types of leadership approaches and organisational commitment (Bass and Avolio 1990). However, this study incorporates the relationship of RL on employees’ turnover intentions and organisational commitment in line with the previous leadership studies. Here, the different domains of RL have distinct relationships (or in some cases, no relationships) with various dimensions of organisational commitment.

Table 3 shows the details of the overall relationship of both the variables and their sub-domains.

We then examined the model with two control variables: age (categorised as 18–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, and above 65 years) and tenure (categorised as less than or up to 1, 2–3, 4–7, 8–11, 12–15, and over 15 years). Both these control variables did not influence the relationships that we specified in this study. For example, age was found as non-significant for both turnover intentions and organisational commitment (.007 and .399, p < .001). Similarly, tenure was non-significant for both turnover intentions and organisational commitment (.030 and .556, p < .001). Table 4 below summarises the findings.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is considered a more sophisticated technique to test any hypothesised model (Podsakoff et al. 2003). However, we carried out the Harman’s one-factor (or single-factor) test and found the total variance of all the used independent variables was well below the cut-off point of 50% (37.75). Hence, it can be suggested that the common method bias does not affect the proposed model.

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between RL and organisational commitment and the mediating effect of employee turnover intentions. The results demonstrate the relevance of studying RL from an employee perspective, and they extend and qualify the literature on the relationships between RL, turnover intention, and organisational commitment in several ways. As predicted in H1, RL was positively related to organisational commitment. The positive relationship between RL and organisational commitment demonstrates that organisations can use RL to enhance employees’ organisational commitment. This result is in line with Doh et al. (2011) Indian study which showed that RL may be an overarching construct that connects employees to the organisation. The inherent relational nature of RL can attract employees to leaders and organisations, thereby increasing employees’ feelings of attachment and belongingness. Such feelings can lead to higher levels of organisational commitment.

As predicted in H2a, RL was negatively related to turnover intentions. The negative relationship between RL and turnover intention explains the value of RL’s relational approach, particularly when examined from an employee perspective. It demonstrates responsible leaders’ ability to develop high-quality relationships with employees as a primary stakeholder of the organisation and as a result attract and engage employees to such an extent that there is little chance of developing turnover intentions. Testing of H2b found a negative relationship between turnover intention and organisational commitment. We used the psychological contract to justify this negative relationship. The results are in line with previous studies showing that the damaged psychological contract is reflected in low commitment and withdrawal behaviours that often accompany turnover intentions (Christian and Ellis 2014). This negative relationship between turnover intention and organisational commitment demonstrates the significance of the relational aspects of the psychological contract. Raja et al. (2004) found that intention to quit was negatively associated with employees’ relational contracts. Strong relational contracts have been shown to relate positively (and transactional contracts, negatively) to organisational commitment (Raja et al. 2004; Millward and Hopkins 1998; Rousseau 1990).

Finally, the results of testing H3 show the critical role employee turnover intention could play in determining the effectiveness of RL in promoting organisational commitment. The results of the study extend conceptual claims of scholars (e.g. Joyce 2006; Myatt 2008; Jung and Kim 2012; Lee et al. 2012) that employee turnover intentions play positive and negative roles depending on the leadership style and organisational commitment. Employee turnover intention was found only to partially mediate the effect of RL on organisational commitment. One explanation for this result could be due to the differences between the types of turnover intentions: organisational-driven and personal-driven turnover intentions (Raja et al. 2004). RL, as measured in this study using Doh et al.’s (2011) scale, is more likely to reduce only organisational-driven turnover intentions (due to superior HR practices, positive stakeholder culture and greater managerial support) than personal-driven turnover intentions (due to career advancement ambitions, etc.). For example, in the case of the latter, an employee could be more passionate about advancing the career at whatever cost. Loyalty and commitment to the responsible leader and the organisation would mean little to them in the face of a promotion or higher salary and perks elsewhere. Another explanation for the partial mediation would be the significance of RL as turnover intention only partially accounts for the effects of RL on organisational commitment.

Implications of the Study

There are several key theoretical and practical implications of this study. In terms of theoretical implications, first, the current study extends our limited understanding of RL and its relationship with an employee outcome, organisational commitment. The study makes a novel contribution to RL literature by drawing attention to the relational element of RL and using SIT as an explanatory concept to examine the relationship of RL and organisational commitment. Second, the current study examines the unique meditational role of turnover intentions in the relationship between RL and organisational commitment. By testing turnover intention’s mediational role, this study departs from earlier studies that use turnover intentions primarily as an outcome variable. Due to the relational approach of RL and because turnover intentions occur in employees still in employment and can be reflected in their commitment levels, we use psychological contract to explain the role of turnover intentions as a mediator between RL and organisational commitment. When employees are able to conceal thoughts of quitting, the study draws attention to the damaged psychological contract between such employees and the organisation, and the impact on organisational commitment. Finally, when employees hold intentions to quit, rather than the transactional element, the relational element of the psychological contract which focuses more on the flexible aspects that presume a long-term relationship with the organisation is likely to be damaged (Christian and Ellis 2014). The study contributes to extant RL theory by drawing attention to the relational elements of an employee’s psychological contract and how with its relational approach, RL can address damage caused to the relational element of the psychological contract.

There are several practical implications as well. First, the results show that RL can influence both employees’ turnover intentions and commitment. Hence, we suggest that organisations should consider RL capability building of managers to motivate and better engage employees. Hence, organisations may introduce specific training and development programmes to help managers to appreciate the significance of RL practices and to examine ways in which to promote these practices. Earlier studies have noted that leadership behaviours can be learned and that training can be useful in the learning process (Barling et al. 1996). Pless et al. (2011) had advised that RL qualities can also be learned outside of a formal training setting. These interventions could involve designing leadership tasks that encourage managers to behave responsibly, thus aligning with employees’ commitment and intentions to stay with their organisations. RL places employees in a primary stakeholder position and provides them an opportunity to be heard and understood. The shareholders of many firms are increasingly demanding that their firms ‘do well by doing good’, which involves developing new business models that align social responsibility with profit maximisation goals (Waldman and Siegel 2008). However, ‘do good’ behaviour also includes designing employee-friendly HR practices and workplaces (Stahl and Luque 2014). Mentors or leadership consultants could be employed to advise managers to adopt and improve RL practices that develop superior HR practices, generate positive stakeholder culture, and provide better managerial support (Doh et al. 2011). These efforts may effectively enhance employee commitment and help reduce turnover intentions.

Second, mediators like employee turnover intentions are not easy to observe because they are latent, unobserved variables. The model in this study, which was constructed based on earlier insights, is used to explain the necessary intermediate processes in the development of RL. This helps to clarify what are the most effective areas on which to place priority to maximise managers’ leadership outcomes and, consequently, employees’ organisational commitment. Third, we suggest that managers who aim to generate higher levels of employees’ organisational commitment over the long term offer new programmes and training workshops that improve RL behaviours. Organisations may choose to revise existing leadership assessment and development practices according to the dimensions that facilitate the execution of RL roles. Therefore, RL can also be regarded from a human resources point of view as an opportunity to move forward in managerial leadership, paying more attention to employees’ organisational commitment and employee turnover intentions.

Limitations of the Study and Research Opportunities

While several limitations exist in the study, they provide opportunities for future researchers. This study collected self-report surveys, and there is a chance that information provided was biased because of socially desirable responses; in other words, participants may tend to present a favourable image of themselves (Johnson and Fendrich 2002). This limitation could be addressed in future by researchers testing the hypothesised conceptual model using different data collection approaches (e.g. rating responses from the perspectives of both managers and employees). This would reduce the likelihood of socially desirable bias, attributing more reliability to the results.

Use of the cross-sectional approach to data collection was another limitation. In contrast to a longitudinal approach, a cross-sectional study does not allow analysing the data with a high degree of confidence. Therefore, future research could aim to replicate findings of the study using longitudinal analysis, as this would allow the development of more consistent and accurate explanations for the causal influence of the constructs and would reveal whether the results using the model developed in this study would change over time.

Future studies could further refine the hypothesised model by using additional mediators (e.g. trust in the manager) or moderators (e.g. work environment). This could add more rigor to the study results. For example, by adding employee trust on supervisors as a study variable, researchers could study the extent to which trust on supervisors could influence leadership effectiveness. By studying the mediation role of trust between RL and organisational commitment, researchers can help improve the theoretical understanding of these concepts and their relationships and develop novel ways to enhance employee commitment at work. Similarly, future studies can extend this model to examine the role of work environment as a moderator between employee turnover intentions and organisational commitment. The inclusion and testing of other employee job-related variables should help develop a more robust model and the likelihood of revealing critical information to promote employee commitment.

Conclusion

Using Social Identity Theory and Psychological Contract, this paper reports on the relationship between RL and organisational commitment, and the mediating role of employee turnover intentions. Taking a different line of inquiry from earlier studies that investigated turnover intentions as an outcome, this study applies turnover intentions as a mediator to examine the relationship between employee perceptions of RL and organisational commitment. The results reveal that perceived RL significantly influences employees’ turnover intentions and organisational commitment. Moreover, the direct relationship between RL and organisational commitment was found to be partially mediated by employees’ turnover intentions. Thus, study results show how RL can promote employee attachment and attraction to their leader and organisation and therefore increase organisational commitment and reduce the harmful effects of employee turnover intentions.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Antunes, A., & Franco, M. (2016). How people in organizations make sense of responsible leadership practices: Multiple case studies. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 37(1), 126–152.

Barling, J., Weber, T., & Kelloway, E. K. (1996). Effects of transformational leadership training on attitudinal and financial outcomes: A field experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(6), 827–832.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1990). The implications of transactional and transformational leadership for individual, team, and organizational development. In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (pp. 231–272). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bass, A. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., & Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 951–968.

Becker, T. E. (1992). Foci and bases of commitment: Are they distinctions worth making? Academy of Management Journal, 35(1), 232–244.

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536.

Bernat, J. (2007). Cutting cost through lower new employee turnover. Retrieved December 27, 2015, from http://www.gallagherbenefits.com/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_24632_550049_0_0_18/HRPulse_0307_Bernat.pdf.

Blau, G. (2007). Does a corresponding set of variables for explaining voluntary organizational turnover transfer to explaining voluntary occupational turnover? Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 70, 135–148.

Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around the organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Brien, A., Thomas, N., & Hussein, A. S. (2015). Turnover intention and commitment as part of organisational social capital in the hotel industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism, 14(4), 357–381.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Ethical readership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Burns, A. C., & Bush, R. F. (2006). Marketing research. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Burris, E. R., Detert, J. R., & Chiaburu, D. S. (2008). Quitting before leaving: The mediating effects of psychological attachment and detachment on voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 912–922.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Cerit, Y. (2010). The effects of servant leadership on teachers’ organizational commitment in primary schools in Turkey. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 13(3), 301–317.

Christian, J., & Ellis, A. (2014). The crucial role of turnover intentions in transforming moral disengagement into deviant behavior at work. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(2), 193–208.

Cohen, J. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. The Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 1140–1157.

Coltman, T., Devinney, T. M., Midgley, D. F., & Venaik, S. (2008). Formative versus reflective measurement models: Two applications of formative measurement. Journal of Business Research, 61(12), 1250–1262.

Dawley, D., Stephens, R., & Stephens, D. (2005). Dimensionality of organizational commitment in volunteer workers: Chamber of commerce board members and role fulfilment. Journal of vocational Behaviour, 67, 511–525.

Doh, J. P., & Quigley, N. R. (2014). Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: Influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 255–274.

Doh, J. P., Stumpf, S. A., & Walter, T. G., Jr. (2011). Responsible leadership helps retain talent in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 85–100.

Donnelly, J. H., & Ivancevich, J. M. (1975). Role clarity and the salesman. Journal of Marketing, 39(1), 71–74.

Edwards, J. R., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psychological Methods, 5(2), 155–174.

Efron, B., & Tibshiriani, R. J. (1993). An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman & Hall.

Fakunmoju, S. B., & Kersting, R. C. (2016). Perceived effects of student loan forgiveness on turnover intention among social workers in Massachusetts. Social Work, 61(4), 331–339.

Faloye, D. O. (2014). Organisational commitment and turnover intentions: Evidence from Nigerian paramilitary organisation. International Journal of Business & Economic Development, 2(3), 23–34.

Fernando, M. (2016). Leading responsibly in the Asian century, Cham, [Ger.]: Springer, [2016]. UOW Catalogue, EBSCOhost. Accessed February 2, 2016.

Fernando, M., & Sim, A. B. (2011). Strategic ambiguity and leaders’ responsibility beyond maximizing profits. European Management Journal, 29(6), 504–513.

Fournier, C., Tanner, J. F., Chonko, L. B., & Manolis, C. (2010). The moderating role of ethical climate on salesperson propensity to leave. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 30(1), 7–22.

Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., & Wicks, A. C. (2007). Managing for stakeholders: Survival, reputation, and success. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gallup, (2009). The Gallup Q12—Employee meaning–Poll 2008 results. Australia Overview, Gallup Consulting. Retrieved February 3, 2010, from http://www.destinationtalent.com.au/blog/wpcontent/uploads/2009/02/the-gallup-q12-poll-2008-australia-10022009.pdf.

Gardner, J. (1990). On leadership. New York: The Free Press.

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumba, F. O. (2005). Can you see the real me? A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343–372.

Gilbreath, B., & Karimi, L. (2012). Supervisor behavior and employee presenteeism. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(1), 114–131.

Greenleaf, R. K. (2002). Servant-leadership: A journey into the nature of legitimate power and greatness. Mahwah: Paulist Press, NJ.

Griffith, J. (2004). Relations of principal transformational leadership to school staff job satisfaction, staff turnover, and school performance. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(3), 333–356.

Grimm, L. G., & Yarnold, P. R. (2000). Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hartman, C. C. (2000). Organizational commitment: Method scale analysis and test of effects. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 8(1), 89–109.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond baron and kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420.

Hirst, G., Walumbwa, F., Aryee, S., Butarbutar, I., & Chen, C. (2016). A multi-level investigation of authentic leadership as an antecedent of helping behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 485–499.

Hogg, M. A. (2001). A social identity theory of leadership. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(3), 184–200.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Structural equation modeling: A multidisciplinary journal. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55.

Jackson, T. A., Meyer, J. P., & Wang, X. H. (2013). Leadership, commitment, and culture: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 20(1), 84–106.

Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 29(4), 351–365.

Johnson, T., & Fendrich, M. (2002). A validation of the crowne–marlowe social desirability scale. St Petersburg: Paper Presented At The American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Joinson, C. (2000). Public sector HR: Leaving bureaucracy behind. HR Magazine, 45(6). Accessed May 22, 2014, from http://www.shrm.org/hrmagazine/2000index/0600/0600joinson.asp.

Joyce, A. (2006). Likeability value as much as job skills, The Honolulu Advertiser. Accessed 12 December 2013, from http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/article/2006/Mar/13/bz/FP603130308.html.

Jung, J., & Kim, Y. (2012). Causes of newspaper firm employee burnout in Korea and its impact on organizational commitment and turnover intention. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(17), 3636–3651.

Kfirat, S., Polat, F., & Yetim, U. (2016). How the poor deal with their own poverty: A social psychological analysis from the social identity perspective. Social Indicators Research, 127(1), 413–433.

Kim, W. G., & Brymer, R. A. (2011). The effects of ethical leadership on manager job satisfaction, commitment, behavioral outcomes, and firm performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30(4), 1020–1026.

Ko, J. W., Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W. (1997). Assessment of Meyer and Allen’s three component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(6), 961–973.

Kotter, J. P. (1990). A force for change: How leadership differs from management. New York: Free Press.

Larson, E. W., & Fukami, C. V. (1984). Commitment to company and union: Parallel models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(3), 367–371.

Lee, D. C., Hung, L. M., & Chen, M. L. (2012). Empirical study on the influence among corporate sponsorship, organizational commitment, organizational cohesiveness and turnover intention. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 2(2), 43–53.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Chenwei, L., & Meuser, J. D. (2014). Servant leadership and serving culture: Influence on individual and unit performance. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1434–1452.

Locke, E. A., Cartledge, N., & Knerr, C. S. (1970). Studies of the relationship between satisfaction, goal setting, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 5(2), 135–158.

Maak, T., & Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership: A relational approach. In T. Maak & N. M. Pless (Eds.), Responsible leadership. New York: Routledge.

Maak, T., Pless, N. M., & Voegtlin, C. (2016). Business statesman or shareholder advocate? CEO responsible leadership styles and the micro-foundations of political CSR. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 463–493.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. M. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171–194.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991a). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991b). Development of organizational commitment during the first year of employment: a longitudinal study of pre- and post-entry influences. Journal of Management, 17(4), 717–733.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(4), 538–551.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Hersovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52.

Millward, L. J., & Hopkins, L. J. (1998). Psychological contracts, organizational and job commitment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(16), 1530–1556.

Miska, C., & Mendenhall, M. E. (2015). Responsible leadership: A mapping of extant research and future directions. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2999-0.

Mobley, W. H. (1977). Intermediate linkage in the relationships between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 237–240.

Mossholder, K. W., Settoon, R. P., & Henagan, S. C. (2005). A relational perspective on turnover: examining structural, attitudinal, and behavioral predictors. Academy of Management Journal, 48(4), 607–618.

Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 14(2), 224–247.

Murray, L. P., Gregoire, M. B., & Downey, R. G. (1991). Organizational commitment of management employees in restaurant operations. Hospitality Research Journal, 14, 339–348.

Myatt, M. (2008). How to reduce employee turnover. Retrieved August 11, 2008, from http://cpnmhn.typepad.com/management_matters/2008/06/how-to-reduce-e.html150.

Ng, T. W. (2016). Theoretical and practitioner letters: Transformational leadership and performance outcomes: Analyses of multiple mediation pathways. Leadership Quarterly. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.11.008.

Ng, T. W., & Sorensen, K. L. (2008). Toward a further understanding of the relationships between perceptions of support and work attitudes: A meta-analysis. Group and Organization Management, 33(3), 243–268.

Nyberg, A., Westerlund, H., Linda, L., Hanson, M., & Theorell, T. (2008). Managerial leadership is associated with self-reported sickness absence and sickness presenteeism among Swedish men and women. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 36(8), 803–811.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–411.

Pless, N. M., Maak, T., & Stahl, G. K. (2011). Developing responsible global leaders through international service- learning programs: The Ulysses experience. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 10(2), 237–260.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Raja, U., Johns, G., & Ntalianis, F. (2004). The impact of personality on psychological contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 350–367.

Raykov, T. (1997). Simultaneous study of group and individual latent longitudinal change patterns using structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 4(3), 212–236.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2000). A first course in structural equation modeling. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714.

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 574–599.

Robinson, S. L., Kraatz, M. S., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Changing obligations and the psychological contract: A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 37(1), 137–152.

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 15(3), 245–259.

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 11(5), 389–400.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Sahi, G. K., & Mahajan, R. (2014). Employees’ organisational commitment and its impact on their actual turnover behaviour through behavioural intentions. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 26(4), 621–646.

Salami, S. O., & Omole, O. A. (2005). Participation in decision making process: Incentives and training as predictors of organisational commitment among industrial workers. African Journal for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 8(2), 210–227.

Samad, S. (2006). The contribution of demographic variables: Job characteristics and job satisfaction on turnover intentions. Journal of International Management Studies, 1(1), 1–12.

Schwerin, M. & Kline, T. (2008). An examination of employee turnover models. Retrieved June 18, 2009, from https://www.nps.edu/Academics/GSBPPAVorkforce.

Stahl, G. K., & Luque, M. D. (2014). Antecedents of responsible leader behavior: A research synthesis, conceptual framework, and Agenda for future research Vienna University of business and economics. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 235–254.

Stogdill, R. (1963). Manual for the leader behavior description questionnaire-form XII. Columbus: Bureau of Business Research, Ohio State University.

Taifor, N.A., Abdullah, H.S. & Hashim, R. (2011). Incidence and antecedents of presenteeism: The case of a federal government ministry in Malaysia. Humanities, science and engineering (CHUSER), IEEE colloquium, PP. 654–659.

Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson Hall.

Tajfel, H. & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of inter-group behaviour. In political psychology: Key readings (Jost, J.T. (Eds.). New York: Psychology Press. PP. 276–279.

Tran, V., Garcia-Prieto, P., & Schneider, S. C. (2011). The role of social identity, appraisal, and emotion in determining responses to diversity management. Human Relations, 64(2), 161–176.

Turner, J. C. (1999). Some current issues in research on social identity and self-categorization theories. In N. Ellemers, S. Spears, & B. Doosje (Eds.), Social identity (pp. 6–34). Oxford: Blackwell.

Turner, J. C. (2010). Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 15–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Voegtlin, C., Patzer, M., & Scherer, A. G. (2012). Responsible leadership in global business: A new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(1), 1–16.

Waldman, D. A. (2014). Bridging the domains of leadership and corporate social responsibility. In D. Day (Ed.), Handbook of leadership and organizations (pp. 541–557). New York: Oxford University Press.

Waldman, D. A., & Balven, R. M. (2014). Responsible leadership: Theoretical issues and research directions. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 224–234.

Waldman, D. A., & Galvin, B. M. (2008). Alternative perspectives of responsible leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 37(4), 327–341.

Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. (2008). Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadership Quarterly, 19(1), 117–131.

Witt, M. A., & Stahl, G. K. (2016). Foundations of responsible leadership: Asian versus Western executive responsibility orientations toward key stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(3), 623–638.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Haque declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Fernando declares that he has no conflict of interest. Author Caputi declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article