Abstract

This study develops a research model that elaborates how responsible leadership and ethical conflict influence employees from the perspectives of role theory and attachment theory. Its empirical results reveal that turnover intention indirectly relates to ethical conflict and responsible leadership via the mediating mechanisms of organizational identification and organizational uncertainty. At the same time, helping intention indirectly relates to ethical conflict and responsible leadership only through organizational identification. Finally, the managerial implications for international business and research limitations based on the empirical results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ethical scandals and irresponsible leaders such as those seen at Enron, Tyco, and Volkswagen have raised strong concerns about business ethics and responsibility in international communities. These concerns have led to close attention being paid to what is theoretically coined as ethical conflict and responsible leadership. Ethical conflict is defined as occurring when individuals feel pressure to take actions that are inconsistent with what they think to be right (Chen and Lee 2016; Dubinsky and Ingram 1984; Uen et al. 2011), whereas responsible leadership is defined as a leader’s demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through inspiring, communicating with, and convincing employees to achieve positive change in workplaces (Seal et al. 2013; Waldman and Siegel 2008). The equal importance of ethical conflict and responsible leadership for employees can be theoretically justifiable based on role theory.

Role theory indicates that social positions in an organization involve an array of associated roles in workplaces (Maak and Pless 2006; Merton 1957). People with one of the positions (e.g., leaders and members) hold expectations for the behaviors of themselves and others (Elanain 2014). For that reason, role theory bridges employees’ and their leader’s acts by clarifying the role expectations they may hold (Mirvis and Seashore 1979). When communicated, these expectations delimit people’s ethical perceptions and responsibilities in their role system (Maak and Pless 2006; Mirvis and Seashore 1979), suggesting the importance of ethical conflict and responsible leadership. For example, Maak and Pless (2006) relate the concept of an integrated role set to propose responsible leadership as a value-based and social-relational phenomenon, which offers a foundational approach in the pursuit of positive organizational change.

Role theory suggests that the role of employees and the role of their leader substantially affect their behavior in workplaces (Chen et al. 2012; Jaramillo et al. 2006; Judge and Piccolo 2004) and hence that ethical conflict (from the role perspective of employees) and responsible leadership (from the role perspective of leaders) together can reveal much greater variance than either variable alone. One premise of role theory is that people (i.e., employees or leaders) define for themselves the specific roles in a firm that make up a conception of the office they occupy, as well as a set of cognitions and perceptions about what should and should not be done by the occupants of the office (Katz and Kahn 1978; Tangirala et al. 2013). These roles govern employees’ moral perceptions among various actions competing for their attention at work (Tangirala et al. 2013). Specifically, when it comes to moral issues, employees’ latitude and dispositions based on these roles can strongly manifest themselves in the extent to which the employees expect themselves to be ethical and to anticipate their leader of being responsible (e.g., Hsu 2012; Ilgen and Hollenbeck 1991; Lin et al. 2009).

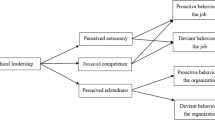

Previous literature has suggested that human resource cost and employee morale are substantially influenced by turnover intention (Fukbua 2016; Organ et al. 2006) and helping intention (Venkataramani and Dalal 2007). For example, Yang et al. (2011) have indicated the importance of turnover intention and interpersonal helping by empirically testing how they are affected by proactive personality. This study aims to explore turnover intention as a negative outcome and helping intention as a positive outcome, which are critical for management to develop a positive atmosphere or climate in the organization (e.g., Benjamin 2012).

Employees’ role conceptualization about themselves and their leader can eventually influence their turnover intention and helping intention. While previous research has long focused on turnover intention and helping intention as outcomes from various motivational aspects (e.g., extrinsic motivation) (e.g., Cao et al. 2013; Kerber 1984; Wang and Yang 2016), there is room for researchers to encompass the causes and implications of the outcomes with regard to present ethical or moral challenges. An extended understanding of business ethics has to take these challenges into account in terms of employees’ ethical belief system as well as that of their leader. For that reason, a significant research gap is on the moral challenges faced by employees and their supervisor in influencing their turnover intention and helping intention. This study bridges the gap between the supervisors’ role focused on responsible leadership and the employees’ role focused on ethical conflict in the development of turnover intention and helping intention. Collectively, this study aims to contribute to the growing body of work on ethical conflict and responsible leadership by simultaneously unraveling the key mediators through which they (i.e., ethical conflict and responsible leadership) influence turnover intention and helping intention in high-tech industry. Complementing previous research, this study is a pioneer in opening the black box that contains these key mediators.

It is important to notify that responsible leadership is related to, but distinct from, ethical leadership, as it draws on the notion of discourse ethics and deliberative democracy, conceptualizes good leadership through leader-employee interaction, and promotes consensual solutions as a criterion of effectiveness (Voegtlin et al. 2012). Previous research (Pless and Maak 2011) has indicated that the main conceptual differences between ethical and responsible leadership stem from their different paradigmatic outlooks. Whereas ethical leadership is concerned with how leaders exploit their ethical guidance to improve effectiveness (e.g., ethical practice of listening, ethical manner, fair decision, and ethical approaches) (Brown et al. 2005), responsible leadership seeks to capture the relational nature between employees and their leader (e.g., communication, emotion, and social relationship) and its implications for matters of responsibility (Cameron and Caza 2005; Pless and Maak 2011).

We conducted a survey on working professionals from Taiwan’s high-tech industry for empirical analyses and sought them out due to two important reasons. First, the high-tech industry has paid great attention to the issue of ethics and irresponsible leadership in recent years in order to retain superior human resources (Azari and Pick 2005; Waldman and Galvin 2008). Second, as the high-tech industry often has a high turnover rate due to its competitive and stressful working environment (Chien and Chen 2007), studying the issue of turnover intention in this industry is critical and helpful for researchers and practitioners. For that reason, working professionals from the high-tech industry make an appropriate sample for this study.

2 Theory and hypotheses’ development

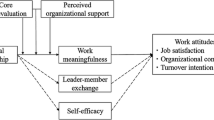

This study proposes a research model that explains turnover intention and helping intention. In the model, turnover intention and helping intention indirectly relate to ethical conflict and responsible leadership via the mediating mechanisms of organizational identification and organizational uncertainty. Previous research on group dynamics has suggested that the reduction of subjective uncertainty and organizational identification should be taken into account simultaneously for understanding social relations (Hogg and Mullin 1999). In an analogous fashion, this study hypothesizes organizational identification and organizational uncertainty as two mediators in our model based on attachment theory. Attachment theory underscores individual variation in the type of relationships individuals have towards a firm (Korsgaard et al. 2003) and suggests that psychological attachment is the basis for organizational identification and uncertainty (e.g., Brown 1969; Lee 1971). The organization often serves as the attachment figure for employees. According to this theory, employees have affective needs for a secure relationship with the organization for which they work (Lin 2010). Previous research supports that attachment theory can explain various aspects of work behavior based on attachment types (e.g., identified, secure, uncertain, or anxious-preoccupied) (Hardy and Barkham 1994), consequently contributing to the retention and motivation of employees (e.g., turnover and helping).

Ethical conflict often arises when employees’ ethical values differ from those perceived to be held by their firm, negatively influencing job-related outcomes (Schwepker 1999). In other words, ethical conflict increases when employees’ personal values clash with those of their firm, and consequently adverse outcomes such as a lack of organizational identification, absenteeism, and turnover intention may occur (Thorne 2010). Previous literature has indicated that individuals’ perceived ethical conflict in the organization can substantially hurt organizational identification (DeConinck 2011), pointing to a negative relationship between ethical conflict and organizational identification.

Contrary to the negative effect of ethical conflict on organizational identification, responsible leadership can positively motivate organizational identification, because responsible leaders can easily flourish employees’ perception of belongingness to the organization through positive discussion by minimizing criticism and negativity, and by replacing them with compliments and supportive communication (Cameron and Caza 2005; Stahl et al. 2013). Responsible leadership is seen as a key predictor of organizational identification (Lynham and Chermack 2006), because it represents a positive role model of being held accountable (e.g., Doh and Quigley 2014) and can transform the self-concept of employees to enhance their feelings of organizational involvement and attachment (Lord et al. 1999; van Knippenberg et al. 2004). More specifically, employees are more likely to identify with an organization when their leader serves as a good role model in terms of responsible behavior and the inclusion of others’ viewpoints or interests (Voegtlin 2011), suggesting a positive relationship between responsible leadership and organizational identification.

Affected by ethical conflict negatively and by responsible leadership positively, organizational identification helps reduce turnover intention. Prior research has shown that organizational identification reveals a strong and negative correlation with turnover intention (Cole and Bruch 2006; Riketta 2005). Identification compensates for estrangement in the domain of employees’ experience (Cheney 2006; Mishra and Bhatnagar 2010) in which weak organizational identification can lead to employees’ feeling of detachment from the organization (Elsbach and Bhattacharya 2001), thus driving employees to contemplate the possibility of leaving the organization (Mishra and Bhatnagar 2010). On the contrary, with their higher organizational identification, employees are less likely to separate their own identity from the perception of their organization’s identity (Elsbach and Bhattacharya 2001), leading to weaker turnover intention (Mishra and Bhatnagar 2010). Collectively, the hypothesis regarding organizational identification as a mediator can be stated as below.

H1a

Organizational identification mediates the positive relationship between ethical conflict and turnover intention.

H1b

Organizational identification mediates the negative relationship between responsible leadership and turnover intention.

Organizational uncertainty is defined in this study as employees’ confusion about organizational purposes and the means of achieving them (e.g., Pfeffer et al. 1976). When organizational uncertainty is high, the effort put forth by employees to do their job often becomes substantially wasted, igniting their attempt to quit the job and to pursue better future career. Role theory states that organizational uncertainty is perceived to be strong when employees’ actions and ethical standards, which are expected based on their role, are dramatically inconsistent or contradictory under different circumstances (e.g., Kahn et al. 1964).

Previous literature has indicated that inherent in all ethical conflicts is uncertainty (Nelson et al. 2008). Ethical conflict can substantially confuse employees and cause their perception of uncertainty in the organization (e.g., organizational changes and job insecurity) to be interpreted as a negative experience or threat rather than as an opportunity for them (Hui and Lee 2000). When ethical conflict occurs, employees feel insecure in their job situation and that control over their own destiny of the job situation is threatened (Hui and Lee 2000). As a result, employees who are confronted by an ethical conflict are likely to perceive stronger organizational uncertainty, consequently increasing the possibility of their quitting the job in the foreseeable future. For example, Huhtala et al. (2015) found that ethical conflict increases perceived uncertainty about their organization and thus causes job tension, frustration, anxiety, dissatisfaction, and poor performance. Similarly, Redman and Fry (2000) indicated that ethical conflict brings about moral uncertainty in the organization, because employees are unsure what moral principles or values apply to a situation (i.e., moral dilemma) (Redman and Fry 2000), suggesting a positive relationship between ethical conflict and organizational uncertainty. On the contrary, when their perceived conflict is reduced, employees feel certain about how things are supposed to go in the organization without having to face many unsure principles, unsettled events, or disagreements in the organization (Pavlish et al. 2011). Ethical conflict has a positive influence on organizational uncertainty, but not vice versa, because organizational uncertainty can be caused by different reasons, such as uncertainty in resources and/or strategies that have no direct effect on ethical issues or conflict at all (Hartlieb and Silvius 2016; Parnell et al. 2000).

Employees under stronger responsible leadership, contrastingly, often perceive weaker organizational uncertainty, because responsible leadership helps them understand and respond to problems and challenges from real-world contexts in an authentic schema that feature positive, organizational goal attainment (Seal et al. 2013). Responsible leadership is the art and ability involved in cultivating, enhancing, and sustaining trust and stability in the organization (Maak 2007), thus reducing organizational uncertainty. Responsible leadership plays a key role in motivating the goodwill that is engendered by the fabric of social relations in the organization and that can effectively facilitate responsible behavior in the organization (Maak 2007; Seeger and Ulmer 2003). That is, responsible leadership can reduce employees’ confusion about organizational purposes by motivating them to contribute to business sustainability and legitimacy (Maak 2007; Seeger and Ulmer 2003).

It is important to note that the nature of responsible leadership is different from other sorts of leadership (e.g., transformational leadership, authentic leadership, etc.) in which it is primarily values-based and driven by the responsible principle of inspiring others toward effecting positive change through the accomplishment of a shared vision (Seal et al. 2013). More specifically, the spirit in responsible leadership is not merely to achieve a business goal, but to pursue a vision that adds value for a wide range of stakeholders and are sustainable (Fernando 2016).

Prior evidence in the literature has showed that employees’ perceived uncertainty in the organization is associated with various behavioral intentions, such as somatic complaints, lack of sleep (e.g., Taber et al. 1979), and intention to quit (Ashford et al. 1989; Hui and Lee 2000; Rosenblatt and Ruvio 1996). A threat due to organizational uncertainty is likely to push employees to seek better opportunities and personal future by leaving the organization (Greenberger and Strasser 1991; Hui and Lee 2000). Consequently the hypothesis regarding the mediating role of organizational uncertainty is derived as below.

H2a

Organizational uncertainty mediates the positive relationship between ethical conflict and turnover intention.

H2b

Organizational uncertainty mediates the negative relationship between responsible leadership and turnover intention.

A meta-analysis (Riketta 2005) regarding organizational identification and its relationship to a variety of work-related attitudes shows that the overall measures of organizational identification are significantly correlated with extra-role behaviors such as providing extra help to co-workers, offering help for special work assignments, etc. (Ouwerkerk et al. 1999; Tyler and Blader 2000). In other words, employees who highly identify with their organization are likely to put in extra effort to help their co-workers (Van Dick et al. 2006). The mediating role of organizational identification herein is consistent with the proposition inherent in the social identity approach whereby employees’ experiences in the social environment are associated with their organizational identification, which in turn guides their behavioral intention for helping in a social environment (Liu et al. 2015; Tajfel and Turner 1979). Hence, the manner in which organizational identification mediates the relationship between helping intention and its predictors can be described as below.

H3a

Organizational identification mediates the negative relationship between ethical conflict and helping intention.

H3b

Organizational identification mediates the positive relationship between responsible leadership and helping intention.

Organizational uncertainty can take various forms of, for instance, drastic organizational changes, downsizing, and merging and has been found to be related to anxiety, anger, or stress (e.g., Hui and Lee 2000; Leana and Feldman 1992). A previous investigation (O’Neill and Lenn 1995; Schweiger and DeNisi 1991) has revealed that employees express anger and skepticism during the period of uncertainty during an organizational restructuring, holding back their helping intention in the workplace. In other words, organizational uncertainty perceived by employees is negatively related to their helping intention, because organizational uncertainty often distracts people’s attention from caring for others due to increased stress, dissatisfaction, and mistrust in the organization (Hui and Lee 2000). To sum up, the hypothesis concerning the mediating role of organizational uncertainty for helping intention can be described as below.

H4a

Organizational uncertainty mediates the negative relationship between ethical conflict and helping intention.

H4b

Organizational uncertainty mediates the positive relationship between responsible leadership and helping intention.

Note that responsible leadership and ethical conflict are related to but not causal to each other because responsible leadership is not a top-down approach for dealing with ethical issues alone (Maak 2007). Previous literature has suggested that the quest for responsible leadership is not limited to ethical conducts (Pless and Maak 2011). As a matter of fact, responsible leadership is more wide-ranging and more relationally oriented than ethical leadership that focuses mainly on moral principles (Antunes and Franco 2016; Maak et al. 2016; Pless and Maak 2011; Seal et al. 2013).

3 Methodology

3.1 Subjects and procedures

We conducted a survey on working professionals from Taiwan’s high-tech industry for empirical analyses and sought them out, because of two important reasons. First, the high-tech industry has paid great attention to the issue of ethics and irresponsible leadership in recent years in order to retain superior human resources (Azari and Pick 2005). Second, as the high-tech industry often has a high turnover rate due to its competitive and stressful working environment (Chien and Chen 2007), studying the issue of turnover intention in this industry is critical for researchers and practitioners. For that reason, working professionals from the high-tech industry make an appropriate sample for this study.

This study has taken two key measures for reducing the threat of common method variances (CMV). First, this study adopted quality measurement items by drawing from and modifying prior literature, refining them based on pilot testing, and eventually using them in the anonymous survey. The literature has supported that CMV can be reduced through the use of high quality scales and an anonymous survey (Feng et al. 2010; Helm and Conrad 2015; Podsakoff et al. 2012). Second, CMV is substantially decreased in this study due to the data collection from two different sources. More specifically, the employees surveyed in this study were asked to measure ethical conflict, organizational uncertainty, and turnover intention, while their corresponding supervisor was asked to measure responsible leadership, organizational identification, and helping intention. The method of our measuring different variables by employees and their corresponding leader respectively is superior to any other post hoc remedial methods for detecting CMV (Baruch and Lin 2012). Previous research has highly recommended that the best way to avoid potential threats of CMV is to allow different variables to be measured by different research subjects (Chang et al. 2010).

The employees from our sample firms were asked to measure ethical conflict, organizational uncertainty, and turnover intention, while their corresponding supervisor was asked to measure responsible leadership, organizational identification, and helping intention. Before our survey, each personnel department of our sample firms randomly solicited for 100 matched pairs of volunteers (including a supervisor and his/her subordinate) and then distributed questionnaires to the pairs (i.e., a total of 500 matched pairs from all our five sample firms). Of the 1000 questionnaires distributed to the working professionals (i.e., 500 for supervisors and another 500 for their corresponding subordinates) at our five sample firms, 252 matched questionnaires (i.e., a matched questionnaire contains one questionnaire from an employee and another one from his/her supervisor) were returned for a questionnaire response rate of 50.4%. Tables 1 and 2 show respectively the sample characteristics and the correction matrix.

3.2 Measures

The variables discussed in this study were measured using 5-point Likert scales translated and modified from prior literature by a focus group familiar with organizational behavior and business ethics. A pilot before the actual survey was conducted to test the quality of our survey instrument. Based on the results of the pilot test with exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the scale items with low reliability, poor factor loadings, or serious cross loadings were refined or dropped by the focus group. Appendix 1 lists all the measurement items, their rater, and literature sources. It is important to take note of responsible leadership in enabling positivity through interpersonal interaction. Cameron and Caza (2005) summarized the traits of positivity, including positive climate, positive calling orientation (i.e., inspiring employees with the sense of work), positive connections, and positive communication. This study used these traits and their examples provided by Cameron and Caza (2005) and Wrzesniewski (2003) for developing measurement items, effectively capturing responsible leadership. For instance, Cameron and Caza (2005) indicated that an obvious way that responsible leaders can enable positive communication is by exemplifying positive talk themselves. This notion is thus included in our measurement item “I often enable communication by exemplifying positive talks.” For that reason, the face validity of our scale items is acceptable.

There are both advantages and disadvantages related to the use of self-reported (Gerlach et al. 2009) or other-reported measures. To mitigate the disadvantages, this study measures factors differently through either self-ratings (e.g., turnover intention is measured by employees themselves, because it relates to individuals’ piracy and is often hidden on purpose from leaders) or other-ratings. Responsible leadership was measured by leaders, because leadership itself is considered to be made up of complex patterns of behavior and multiple leader attributes (Zaccaro 2007). Previous literature has suggested that responsible leadership is a kind of values-centered leadership (i.e., supervisors’ value) (Cameron and Caza 2005) and is also a self-referential concept that is about “being true to one’s self” (Freeman and Auster 2011). Hence, responsible leadership is measured by supervisors in this study to capture its authenticity (Maak and Pless 2006; Pless and Maak 2011). As another example, Peccei et al. (2008) have demonstrated that measurements for the extent that employees are committed to the values of the organization using managers’ reports are both reliable and valid. In a similar fashion, the extent to which employees identify with their organization was measured by supervisors in this study as the proxy of organizational identification.

4 Data analysis

The survey data were analyzed using a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) (Anderson and Gerbing 1998). The measurement model testing was conducted as the first step of SEM, with the test results and goodness-of-fit indices in Table 3. The comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI) were close to or exceeded 0.90, while the root-mean-square residual (RMR) was smaller than 0.05, and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) was smaller than 0.08 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). All in all, the test results supported that the measurement model of this study fits its empirical data very well.

Convergent validity was statistically accepted in this study (see Table 3), because: (1) all factor loadings were statistically significant; (2) the average variance extracted (AVE) for each variable was greater than 0.50; and (3) the reliabilities all exceeded 0.80 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Chi square difference tests were applied to evaluate discriminant validity. As Chi square difference statistics for all pairs of constructs in Table 4 exceeded their critical value based on the experiment-wise error rate at an overall significance level of 0.01, discriminant validity was confirmed.

The second step of SEM performed the structural model testing with gender, age, and tenure of employees as control variables. Table 5 presents the statistical results of our SEM analysis, indicating that seven out of eight model paths in Table 5 were significant at the 0.01 level. In summary of Table 5, turnover intention was negatively related to organizational identification which was then associated with ethical conflict negatively and with responsible leadership positively (thus, H1a and H1b are supported). Furthermore, turnover intention was positively related to organizational uncertainty which was then associated with ethical conflict positively and with responsible leadership negatively (thus, H2a and H2b are supported). Helping intention was positively related to organizational identification which was then associated with ethical conflict negatively and with responsible leadership positively (therefore, H3a and H3b are supported). Finally, there is no significant relationship between turnover intention and organizational uncertainty, while organizational uncertainty was associated with ethical conflict positively and with responsible leadership negatively (H4a and H4b are not supported). Table 6 summarizes the results.

Despite the statistical results in Table 5, this study further conducts post hoc analysis to test if there are possible direct effects of ethical conflict and responsible leadership on the outcomes. The test results in the post hoc analysis show that ethical conflict does not have any direct effect on turnover intention and helping intention, and that responsible leadership does not have any direct effect on turnover intention. However, responsible leadership shows a direct and significant effect on helping intention, leading to a consistent result with our preceding analysis that our H4 is not supported. Collectively, these results explain that responsible leadership is likely to affect helping intention directly rather than indirectly through organizational uncertainty. Nevertheless, the test results for the unsupported hypothesis in this study warrant more in-depth research—for instance, taking some moderators into account so that the authentic reason behind the unsupported hypothesis can be accurately interpreted. In addition, we conduct further analysis of competing models suggested by Avolio et al. (2003) in order to ensure that our research model is tentatively acceptable among different competing models. The fit indices of the validation models in Appendix 2 confirm that our research model based on a total of six factors is the best among six competing models.

We conducted further tests for confirming the indirect effect of ethical conflict and responsible leadership respectively in our research model (see Table 7). Specifically, the simultaneous overall tests of SEM were used in this study to investigate the indirect effect of ethical conflict and responsible leadership on their outcome (i.e., turnover intention or helping intention respectively). Unlike the traditional regression with several discrete testing steps for indirect effects, SEM provides a powerful method for verifying the indirect effect by simultaneously including an outcome, its mediator, and predictor. The test results in Table 7 show that ethical conflict has significant indirect effects respectively on turnover intention with the estimate of 0.30 (p < .01) and on helping intention with the estimate of −0.05 (p < .05). Moreover, responsible leadership has significant indirect effects respectively on turnover intention with the estimate of −0.35 (p < .01) and on helping intention with the estimate of 0.18 (p < .01).

5 Discussion

The empirical results of this study provide useful findings that complement the international business literature on turnover intention and helping intention. Specifically, this study finds that ethical conflict and responsible leadership can help explain the formation of turnover intention and helping intention. At the same time, the dual mediating roles of organizational identification and organizational uncertainty provide critical implications that have never been examined and discussed in previous literature. Based on these results, this study presents theoretical and managerial implications as follows.

5.1 Theoretical implications

The findings of this study have three major theoretical implications. First, the finding about the significant effect of organizational identification on helping intention complements previous literature concerning the social identity model of deindividuation effects (Levine et al. 2010), which reveals the effect of social identities on deindividuation conditions (e.g., high group immersion, salient social identifies) (Postmes et al. 1999) and helping behavior.

Second, the joint effect of organizational uncertainty and organizational identification on turnover intention provides a compelling empirical evidence that simultaneously supports uncertainty reduction theory (Berger and Calabrese 1975) and social categorization theory (Tajfel 1981). While uncertainty reduction theory argues that employees seek to reduce the uncertainty with a more secure approach (e.g., gathering more information, searching for a better job, etc.), social categorization theory argues in the principle of comparative fit—that only the organization with which employees believe they share similar attributes will be valued as credible and attractive for their pursuit of its membership (Chou and Chen 2016; Chou et al. 2016; Haslam and Turner 1998; Liou and Tsai 2016; Oakes 1987; Yao et al. 2016). Specifically, this study’s model that takes into account both organizational uncertainty and organizational identification provides a unique contribution to enrich the literature as these two theories have not been previously integrated together to assess employees’ behavioral intention. If organizational uncertainty and organizational identification are not simultaneously examined in a single model setting, researchers may mistakenly think the issues of turnover and helping are much simpler than what they really are.

Third, the effect of ethical conflict on organizational identification negatively and on organizational uncertainty positively complements the theoretical discussion by Victor and Cullen (1987) about deontology in which an unethical workplace climate (e.g., a lack of equity) discourages employees from investing in identity attachments to the organization, thus eventually influencing their future career decision (e.g., turnover).

5.2 Managerial implications

The findings of this study offer fresh insights into turnover intention and helping intention and how they are influenced indirectly by ethical conflict and responsible leadership through organizational identification or organizational uncertainty. Management can take measures to reduce turnover intention by, for example, emphasizing and maximizing internal similarities (within the firm) and external differences with other firms (i.e., to improve organizational identification) (e.g., Prati and Zani 2013). It is also important for managers to increase organizational stability with transparent information flows in the firm so that organizational uncertainty and turnover intention can be substantially reduced (e.g., Stonebraker and Liao 2004). Employees and their leader should make a concerted effort to fine-tune their vision, which can become a clear guidance that substantially reduces organizational uncertainty. As a result, the vision shared by employees may alleviate ethical conflict (due to, for example, consensus for dealing with disagreements) and improve mutual understanding between them and their leader (due to, for example, quality reciprocal relationship).

As ethics is critically vital for a business organization, management should continuously strive for detecting potential ethical conflict between the employees and the organization, so as to help arrange effective solutions (e.g., open discussion for business ethics, reflections on current company policies, etc.) to mitigate the conflict. Employees should be supported by their leader to design the work context that gives them an opportunity to make their work meaningful and consequently increases their confidence to solve ethical controversies in the workplace. The work environment, organizational policies, and HR practices should all favor ethical considerations. Employees should be trained through ethical mentoring to persist in being willing to whistle blow against unethical matters. Ethical compatibility should be taken into consideration during the recruitment and selection so that the value fit between employees and the organization can be enhanced in a long run. One-on-one employee counseling that promotes professional and business ethics in the organization should be periodically provided to all employees in the firm.

In addition to the emphasis on the reduction of ethical conflict, top management should encourage supervisors to take responsibility in a professional way as a good role model for subordinates. Responsible behavior based on transparency and correctness should be valued more strongly than obedient behavior without reasoning, and the conduct of being responsible should be embedded as a part of career advancement roadmap and leader training for supervisors or mangers. A responsible leader can intellectually inspire subordinates if his/her own job allows himself/herself to communicate with subordinates individually, visualize new opportunities, diagnose potential problems, and develop effective solutions. The organization that pushes leaders or managers to pay close attention only to trivia without encouraging them to communicate with and inspire employees are unlikely to influence the employees for achieving lower turnover intention and higher helping intention.

A leader who shirks his/her responsibilities and relies on subordinates to work on their own without guiding or supporting them can substantially damage workforce morale. An irresponsible leader creates a culture of irresponsibility throughout the organization. Therefore, it is necessary to place the onus on the leader to identify solutions for his/her irresponsibility by asking the leader to suggest ways for his/her leadership improvement so that the improvement can be fairly evaluated in the future. Collectively, once an organization achieves a reduction in ethical conflict and an increase in responsible leadership, employees’ organizational identification will be significantly increased and organizational uncertainty will also lessen.

In summary, a firm that builds a strong ethical climate as guidance for reducing ethical conflict and for boosting responsible leadership can be assured of making employees identify strongly with their organization and to generate their intention of helping others and staying at the firm (rather than quitting the job). Taking full responsibility as a great leader actually involves accountability, communicative competence, comprehension, dependability, and reliability, implying these characteristics’ far-reaching and inclusive meaningfulness in business ethics. Responsible leadership should pursue the ultimate best—well-being of employees—through the development of manager-employee relationship quality and organizational identification. Overall, the reduction of ethical conflict and the enhancement of responsible leadership should be considered as an organization’s lubricant that smoothes its holistic business operations.

5.3 Limitations

Despite our best efforts to conduct this study, two limitations may be noticed. The first limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this study due to collecting data in the same period of time. This limitation might restrain the explanatory power of this research to justify causal inferences. Second, this research only investigates working professionals from a single industry: Taiwan’s high-tech industry. Therefore, the implications drawn from this study might not be completely generalizable for detecting the turnover intention and helping intention of employees in traditional industries such as the banking industry, food industry, tourist industry, etc.

The insignificant relationship between organizational uncertainty and helping intention in this study may be caused by teaming work modes of our sample subjects in Taiwan’s high-tech industry. Teaming work modes that are very popular in high-tech industry and emphasize highly coordination, interdependence, and mutual support are likely to make helping intention irrelevant to organizational uncertainty. Future research may compare how various work modes influence the relationship between organizational uncertainty and turnover intention so that their direct linkage can be authentically verified under different circumstances.

Besides, future scholars are advised to collect longitudinal data from international business organizations and include a wide variety of factors concerning business ethics (e.g., ethical efficacy, ethical fit, ethical norm, and ethical stress) from different aspects of academic theories so as to verify turnover intention and helping intention from broader viewpoints. Last but not least, the test results herein that disconfirm one hypothesis (i.e., the unsupported H4) may be further examined in the future so that the relationship between helping intention, turnover intention, and many other mediators can be authentically verified.

References

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1998) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Antunes A, Franco M (2016) How people in organizations make sense of responsible leadership practices: multiple case studies. Leadersh Organ Dev J 37(1):126–152

Ashford SJ, Lee C, Bobko P (1989) Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: a theory-based measure and substantive test. Acad Manag J 32(4):803–829

Avolio BJ, Sivasubramaniam N, Murray WD, Jung D, Garger JW (2003) Assessing shared leadership: development and preliminary validation of a Team Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. In: Pearce CL, Conger JA (eds) Shared leadership. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 143–172

Azari R, Pick JB (2005) Technology and society: socioeconomic influences on technological sectors for United States counties. Int J Inf Manag 25(1):21–37

Baruch Y, Lin CP (2012) All for one, one for all: coopetition and virtual team performance. Technol Forecast Soc Change 79(6):1155–1168

Benjamin A (2012) Human resource development climate as a predictor of citizenship behaviour and voluntary turnover intentions in the banking sector. Int Bus Res 5(1):110–119

Berger CR, Calabrese RJ (1975) Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Commun Res 1(2):99–112

Brown M (1969) Identification and some conditions of organizational involvement. Adm Sci Q 14(3):346–355

Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA (2005) Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 97(2):117–134

Cameron K, Caza A (2005) Developing strategies and skills for responsible leadership. In: Doh JP, Stumpf SA (eds) Handbook on responsible leadership and governance in global business. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham/Northampton, pp 87–111

Cao Z, Chen J, Song Y (2013) Does total rewards reduce the core employees’ turnover intention? Int J Bus Manag 8(20):62–75

Chang SJ, Van Witteloostuijn A, Eden L (2010) From the editors: common method variance in international business research. J Int Bus Stud 41(2):178–184

Chen D-H, Lee Y-H (2016) The intraday price discovery of Taiwan’s dual-trading foreign exchange market. Corp Manag Rev 36(2):65–104

Chen C-HV, Chang W-C, Lee H-M, Yuan M-L (2012) Effects of leader-member exchange and locus of control on job attitudes: the mediation of psychological empowerment. Chiao Da Manag Rev 32(2):77–104

Cheney G (2006) The rhetoric of identification and the study of organizational communication. In: Putnam LL, Krone KJ (eds) Organizational communication. Sage, New Delhi, pp 257–276

Chien CF, Chen LF (2007) Using rough set theory to recruit and retain high-potential talents for semiconductor manufacturing. IEEE Trans Semicond Manuf 20(4):528–541

Chou C-K, Chen M-L (2016) A qualitative study on perceived value and loyalty: a moderated-mediation framework. Corp Manag Rev 36(2):105–122

Chou C, Yang K-P, Chiu Y-J (2016) Coupled open innovation and innovation performance outcomes: roles of absorptive capacity. Corp Manag Rev 36(1):37–68

Cole MS, Bruch H (2006) Organizational identity strength, identification, and commitment and their relationships to turnover intention: does organizational hierarchy matter? J Organ Behav 27(5):585–605

Colquitt JA, LePine JA, Piccolo RF, Zapata CP, Rich BL (2012) Explaining the justice–performance relationship: trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer? J Appl Psychol 97(1):1–15

DeConinck JB (2011) The effects of ethical climate on organizational identification, supervisory trust, and turnover among salespeople. J Bus Res 64(6):617–624

Doh JP, Quigley NR (2014) Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Acad Manag Perspect 28(3):255–274

Dubinsky AJ, Ingram TN (1984) Correlates of salespeople’s ethical conflict: an exploratory investigation. J Bus Ethics 3(4):343–353

Elanain HMA (2014) Leader-member exchange and intent to turnover: testing a mediated-effects model in a high turnover work environment. Manag Res Rev 37(2):110–129

Elsbach KD, Bhattacharya CB (2001) Defining who you are by what you’re not: organizational disidentification and the National Rifle Association. Organ Sci 12(4):393–413

Feng T, Sun L, Zhang Y (2010) The effects of customer and supplier involvement on competitive advantage: an empirical study in China. Ind Mark Manag 39(8):1384–1394

Fernando M (2016) Responsible leadership in the Asian century. In: Leading responsibly in the Asian century. Springer, pp 143–176

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388

Freeman RE, Auster ER (2011) Values, authenticity, and responsible leadership. J Bus Ethics 98(1):15–23

Fukbua C (2016) A proposed ODI to improve motivation and loyalty among engineers: a case study of UNC Company. Int Res E J Bus Econ 2(1):1–13

Gerlach JH, Kuo FYB, Lin CS (2009) Self sanction and regulative sanction against copyright infringement: a comparison between US and China college students. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol 60(8):1687–1701

Greenberger DB, Strasser S (1991) The role of situational and dispositional factors in the enhancement of personal control in organizations. In: Cummings LL, Staw BM (eds) Research in organizational behavior, vol 13. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 111–145

Hardy GE, Barkham M (1994) The relationship between interpersonal attachment styles and work difficulties. Hum Relat 47(3):263–281

Hartlieb S, Silvius G (2016) Dealing with uncertainty in projects: what project management can learn from business development. In: The proceedings of fifth international scientific conference on project management in the Baltic countries April 14–15, 2016, Riga, University of Latvia, pp 141–158

Haslam SA, Turner JC (1998) Extremism and deviance: beyond taxonomy and bias. Soc Res 65(2):435–448

Helm R, Conrad D (2015) The impact of customer-specific and market-related variables on the preference for highly innovative products. Rev Manag Sci 9(1):61–88

Hogg MA, Mullin B-A (1999) Joining groups to reduce uncertainty: subjective uncertainty reduction and group identification. In: Abrams D, Hogg MA (eds) Social identity and social cognition. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 249–279

Hsu C-T (2012) The relationship between stress and nursing errors: the moderating role of professional ethics. Chiao Da Manag Rev 32(2):1–36

Huhtala M, Kaptein M, Feldt T (2015) How perceived changes in the ethical culture of organizations influence the well-being of managers: a two-year longitudinal study. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 25(3):1–18

Hui C, Lee C (2000) Moderating effects of organization-based self-esteem on organizational uncertainty: employee response relationships. J Manag 26(2):215–232

Ilgen DR, Hollenbeck JR (1991) The structure of work: job design and roles. In: Dunnette MD, Hough LM, Dunnette MD, Hough LM (eds) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, vol 2, 2nd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, pp 165–207

Jaramillo F, Mulki JP, Solomon P (2006) The role of ethical climate on salesperson’s role stress, job attitudes, turnover intention, and job performance. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 26(3):271–282

Judge TA, Piccolo RF (2004) Transformational and transactional leadership: a meta-analytic test of their relative validity. J Appl Psychol 89(5):755–768

Kahn RL, Wolfe DM, Quinn RP, Snoek JD, Rosenthal RA (1964) Organizational stress: studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley, New York

Kammeyer-Mueller JD, Simon LS, Rich BL (2012) The psychic cost of doing wrong ethical conflict, divestiture socialization, and emotional exhaustion. J Manag 38(3):784–808

Katz D, Kahn RL (1978) The social psychology of organizations. Wiley, New York

Kerber KW (1984) The perception of nonemergency helping situations: costs, rewards, and the altruistic personality. J Personal 52(2):177–187

Korsgaard MA, Brodt SE, Sapienza HJ (2003) Trust, identity and attachment: Promoting individuals’ cooperation in groups. In: West M, Tjosvold D, Smith K (eds) International handbook of organizational teamwork and cooperative working. Wiley, West Sussex, pp 113–130

Leana CR, Feldman DC (1992) Coping with job loss: how individuals, organizations, and communities respond to layoffs. Lexington Books, New York

Lee S (1971) An empirical analysis of organizational identification. Acad Manag J 14(2):213–226

Levine M, Cassidy C, Jentzsch I (2010) The implicit identity effect: identity primes, group size, and helping. Br J Soc Psychol 49(4):785–802

Lin CP (2006) To help or not to help: understanding the helping intentions from a mediating perspective of social network ties. J Bus Ethics 63(2):175–182

Lin CP (2010) Modeling corporate citizenship, organizational trust, and work engagement based on attachment theory. J Bus Ethics 94(4):517–531

Lin GTR, Shen Y-C, Hu J-F, Sun C-C (2009) Constructing and employing the appraising model of intangible assets. Chiao Da Manag Rev 29(2):131–161

Liou F-M, Tsai Y-H (2016) Latent trajectories of competitive heterogeneity: bridging the gap in theories between persistent performance and value creation. Corp Manag Rev 36(1):1–36

Liu C-C, Chen S-Y, Liao C-H (2015) The relationships among emotional capital, job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: a cross-level analysis. Chiao Da Manag iew 35(1):1–24

Lord RG, Brown DJ, Freiberg SJ (1999) Understanding the dynamics of leadership: the role of follower self-concepts in the leader/follower relationship. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 78(3):167–203

Lynham SA, Chermack TJ (2006) Responsible leadership for performance: a theoretical model and hypotheses. J Leadersh Organ Stud 12(4):73–88

Maak T (2007) Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. J Bus Ethics 74(4):329–343

Maak T, Pless NM (2006) Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society: a relational perspective. J Bus Ethics 66(1):99–115

Maak T, Pless NM, Voegtlin C (2016) Business statesman or shareholder advocate? CEO responsible leadership styles and the micro-foundations of political CSR. J Manag Stud 53(3):463–493

Mael F, Ashforth BE (1992) Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J Organ Behav 13(2):103–123

Merton RK (1957) The role-set: problems in sociological theory. Br J Sociol 8(2):106–120

Mirvis PH, Seashore SE (1979) Being ethical in organizational research. Am Psychol 34(9):766–780

Mishra SK, Bhatnagar D (2010) Linking emotional dissonance and organizational identification to turnover intention and emotional well-being: a study of medical representatives in India. Hum Resour Manag 49(3):401–419

Nelson WA, Weeks WB, Camfield JM (2008) The organizational costs of ethical conflicts. J Health Care Manag 53(1):41–52

O’Neill HM, Lenn J (1995) Voices of survivors: words that downsizing CEOs should hear. Acad Manag Executive 9(4):23–34

Oakes PJ (1987) The salience of social categories. In: Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS (eds) Rediscovering the social group: a self-categorization theory. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 117–141

Organ DW, Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB (2006) Organizational citizenship behavior: its nature, antecedents, and consequences. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Ouwerkerk JW, Ellemers N, de Gilder D (1999) Social identification, affective commitment and individual effort on behalf of the group. In: Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje BJ (eds) Social identity: context, commitment, content. Blackwell, Oxford, pp 184–204

Parnell JA, Lester DL, Menefee ML (2000) Strategy as a response to organizational uncertainty: an alternative perspective on the strategy-performance relationship. Manag Decis 38(8):520–530

Pavlish C, Brown-Saltzman K, Hersh M, Shirk M, Nudelman O (2011) Early indicators and risk factors for ethical issues in clinical practice. J Nurs Scholarsh 43(1):13–21

Peccei R, Bewley H, Gospel H, Willman P (2008) Look who's talking: sources of variation in information disclosure in the UK. Br J Ind Relat 46(2):340–366

Pfeffer J, Salancik GR, Leblebici H (1976) The effect of uncertainty on the use of social influence in organizational decision making. Adm Sci Q 21(2):227–245

Pless NM, Maak T (2011) Responsible leadership: pathways to the future. J Bus Ethics 98(1):3–13

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569

Postmes T, Spears R, Lea M (1999) Social identity, group norms, and “deindividuation”: lessons from computer-mediated communication for social influence in the group. In: Ellemers N, Spears R, Doosje B (eds) Social identity: context, commitment, content. Blackwell, Oxford

Prati G, Zani B (2013) The relationship between psychological empowerment and organizational identification. J Community Psychol 41(7):851–866

Redman BK, Fry ST (2000) Nurses’ ethical conflicts: what is really known about them? Nurs Ethics 7(4):360–366

Riketta M (2005) Organizational identification: a meta-analysis. J Vocat Behav 66(2):358–384

Rosenblatt Z, Ruvio A (1996) A test of a multidimensional model of job insecurity: the case of Israeli teachers. J Organ Behav 17(s1):587–605

Schwepker Jr CH (1999) Research note: the relationship between ethical conflict, organizational commitment and turnover intentions in the salesforce. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 19(1):43–49

Schweiger DL, DeNisi AS (1991) Communication with employees following a merger: a longitudinal field experiment. Acad Manag J 34(1):110–135

Seal CR, Royce-Davis J, Miguel K, Andrews-Brown A (2013) Developing capacity for responsible leadership. In: Riggio Ronald E, Tan Sherylle J (eds) Leader interpersonal and influence skills: the soft skills of leadership. Routledge, New York, pp 256–276

Seeger MW, Ulmer RR (2003) Explaining Enron: communication and responsible leadership. Manag Commun Q 17(1):58–84

Stahl GK, Pless NM, Maak T (2013) Responsible global leadership. In: Mendenhall ME, Osland J, Bird A, Oddou GR, Maznevski ML, Stahl GK (eds) Global leadership: research, practice, and development. Routledge, New York, pp 240–259

Stonebraker PW, Liao J (2004) Environmental turbulence, strategic orientation: modeling supply chain integration. Int J Oper Prod Manag 24(10):1037–1054

Taber TD, Walsh JT, Cooke RA (1979) Developing a community-based program of reducing the social impact of a plant closing. J Appl Behav Sci 15(2):133–155

Tajfel H (1981) Human groups and social categories: studies in social psychology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Tajfel H, Turner J (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worschel S (eds) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, pp 33–47

Tangirala S, Kamdar D, Venkataramani V, Parke MR (2013) Doing right versus getting ahead: the effects of duty and achievement orientations on employees’ voice. J Appl Psychol 98(6):1040–1050

Thorne L (2010) The association between ethical conflict and adverse outcomes. J Bus Ethics 92(2):269–276

Tyler TR, Blader SL (2000) Cooperation in groups. Procedural justice, social identity, and behavioral engagement. Psychology Press, Philadelphia

Uen J-F, Wu T, Tsai H-C (2011) Ethical climate and its relationship to ethical behavior and ethical mechanisms. Chiao Da Manag Rev 31(2):33–60

Valentine S, Hollingworth D, Eidsness B (2014) Ethics-related selection and reduced ethical conflict as drivers of positive work attitudes: delivering on employees’ expectations for an ethical workplace. Pers Rev 43(5):692–716

Van Dick R, Grojean MW, Christ O, Wieseke J (2006) Identity and the extra mile: relationships between organizational identification and organizational citizenship behaviour. Br J Manag 17(4):283–301

van Knippenberg D, van Knippenberg B, De Cremer D, Hogg MA (2004) Leadership, self and identity: a review and research agenda. Leadersh Q 15(6):825–856

Venkataramani V, Dalal RS (2007) Who helps and harms whom? relational antecedents of interpersonal helping and harming in organizations. J Appl Psychol 92(4):952–966

Victor B, Cullen JB (1987) A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. In: Frederick WC (ed) Research in corporate social performance and policy, vol 9. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 51–71

Voegtlin C (2011) Development of a scale measuring discursive responsible leadership. J Bus Ethics 98(s1):57–73

Voegtlin C, Patzer M, Scherer AG (2012) Responsible leadership in global business: a new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes. J Bus Ethics 105(1):1–16

Waldman DA, Galvin BM (2008) Alternative perspectives of responsible leadership. Organ Dyn 37(4):327–341

Waldman DA, Siegel D (2008) Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadersh Q 19(1):117–131

Wang YD, Yang C (2016) How appealing are monetary rewards in the workplace? A study of ethical leadership, love of money, happiness, and turnover intention. Soc Indic Res 129(3):1277–1290

Wrzesniewski A (2003) Finding positive meaning in work. In: Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE (eds) Positive organizational scholarship. Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc., San Francisco, pp 296–308

Yang J, Gong Y, Huo Y (2011) Proactive personality, social capital, helping, and turnover intentions. J Manag Psychol 26(8):739–760

Yao C-Y, Shang SSC, Yu Y-C (2016) The retention of customer relationships after mergers and acquisitions. Corp Manag Rev 36(2):65–104

Zaccaro SJ (2007) Trait-based perspectives of leadership. Am Psychol 62(1):6–16

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported by Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Measurement items

Turnover intention (measured by employees)

-

TI1. I intend to look for a job outside of current company within the next year.

-

TI2. I have no intention to remain indefinitely within this company.

-

TI3. I often think about quitting my job.

-

Source: Cole and Bruch (2006)

Helping intention (measured by supervisors)

-

HI1. This employee helps others who have heavy workloads.

-

HI2. This employee helps others who have been absent from work.

-

HI3. This employee willingly helps others who have work-related problems.

-

HI4. This employee helps orient new employees even though it is not required.

-

Source: Lin (2006)

Organizational identification (measured by supervisors)

-

OI1. This employee demonstrates strong ties with the firm.

-

OI2. This employee shows a strong sense of belonging to the firm.

-

OI3. This employee presents to be proud to work for the company.

-

OI4. Overall, this employee reveals a strong identification with the firm.

-

Source: Mael and Ashforth (1992)

Organizational uncertainty (measured by employees)

-

OU1. There is a lot of uncertainty in our company.

-

OU2. Many things seem unsettled in my company most of time.

-

OU3. If I think about work, I feel a lot of uncertainty.

-

OU4. I cannot predict how things will go in my company.

-

Source: Colquitt et al. (2012)

Responsible leadership (measured by supervisors)

-

RL1. I often enable communication by exemplifying positive talks. (Positive communication)

-

RL2. I am concerned about employee emotion. (Positive climate)

-

RL3. I develop quality social relationship in workplaces. (Positive connection)

-

RL4. I am capable of inspiring employees (Positive inspiration).

-

RL5. I am responsible for achieving positive change in the firm.

-

RL6. Overall, being responsible is highly important for my job.

-

Source: Cameron and Caza (2005)

Perceived ethical conflict (measured by employees)

-

EC1. In order to succeed in my company, it is often necessary to compromise one’s ethics

-

EC2. There exists a conflict between my company’s rules and what I feel is right.

-

EC3. There exists a conflict between my personal ethical values and the directives of my company,

-

Source: Kammeyer-Mueller et al. (2012); Valentine et al. (2014)

Appendix 2: Fit indices of this study’s validation models

Models | χ2 | df | χ2/df | NNFI | NFI | CFI | RMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Model 1 | 2495.78 | 252 | 9.90 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.14 | 0.19 |

Model 2 | 2126.07 | 251 | 8.47 | 0.49 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.12 | 0.17 |

Model 3 | 1735.45 | 249 | 6.97 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.12 | 0.15 |

Model 4 | 1338.83 | 246 | 5.44 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

Model 5 | 915.74 | 242 | 3.78 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

Model 6 | 508.47 | 237 | 2.15 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, CM., Lin, CP. Assessing the effects of responsible leadership and ethical conflict on behavioral intention. Rev Manag Sci 12, 1003–1024 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0236-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0236-1

Keywords

- Ethical conflict

- Responsible leadership

- Turnover intention

- Organizational identification

- Helping intention

- International business