Abstract

This study aims to investigate the effect of ethical leadership on employee attitudes (affective commitment and job satisfaction) and to examine the role of psychological empowerment as a potential mediator of these relationships. In total, 467 employees in Chinese public sector completed surveys across three separate waves. Confirmatory factor analysis and structural equation modeling were used to test hypotheses. The paper found a positive relationship between ethical leadership and both employee attitudes and further reveals that psychological empowerment fully mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment while partially mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction. Testing of above relationships via a mediated approach is novel and contributes to the research on ethical leadership.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the past few decades, theorists have believed that ethics plays an important role in evolving good characters among individuals for the prosperity and thrive of both societies and its members. Generally, leaders are needed to establish moral standards for their followers to resolve such activities that are unfavorable to the welfare of society and certain organization (Aronson 2001). The morally responded uncertain business practices under current economic circumstances have resulted in a great need for ethical leadership and it has become a more expanding area to be inquired (Treviño et al. 2006). Comprehensively, ethical leadership is defined as ‘‘the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (Brown et al. 2005). Additionally, it can also be observed from both empirical (Bass and Steidlmeier 1999) and philosophical aspects (Ciulla 2014).

In this regard, Brown et al. (2005) established ethical leadership scale which contains notable characteristics of authentic (Avolio and Gardner 2005), charismatic (Conger and Kanungo 1998) and transformational leadership styles (Bass 1985). Most notably, the study of ethical leadership states that leader’s behavior is much critical for achieving a positive outcome in organizations (Koh and El’Fred 2001; Petrick and Quinn 2001; Treviño et al. 2003).

Leaders in different positions play a critical role in establishing a sustainable organizational culture among employees (Grojean et al. 2004). In line with House (1976) and Bass (1985), theories of charismatic and transformational leadership determine different processes through which influences occur and employees observe those influences and their consequences frequently (Bandura 1986).

Ethical leadership is as important as it has a positive effect on the employees work behaviors in public sector organizations. Several studies indicate that ethical leadership has positive and significant relation with numerous dimensions of leadership effectiveness including employees’ motivation, job satisfaction, performance and commitment (Brown and Treviño 2006; Newman et al. 2015; Ofori 2009). In spite of these systematic approaches by which ethical leaders influence and inspire their subordinates have not been explored thoroughly (Avey et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2012), and various scholars have suggested paying more attention to understand how these influential activities operated in ethical leadership (Bouckenooghe et al. 2015; Newman et al. 2014; Newman and Sheikh 2012; Walumbwa et al. 2011).

Despite the limited theoretical and empirical research in this area, the present study aimed to explore the relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ basic work-related outcomes including job satisfaction and commitment. Basically, job satisfaction is a key element in organizations which influences citizenship behaviors and both employees’ performance and attitudes (Brown and Treviño 2006; Judge and Bono 2001). Intrinsically, among other leadership styles, ethical leadership highly inspires employees’ sense of satisfaction towards their work and generally tends to organizational success (Avey et al. 2012; Bouckenooghe et al. 2015) while unethical behaviors impact negatively on job satisfaction (Liu and Lin 2018; Vitell and Davis 1990). On the other hand organizational commitment is an employees’ influential strength of identification and engagement within a specific organization (Mowday et al. 1982) and can be categorized into three broad aspects like work experience, personal and organizational factors (Eby et al. 1999). Previous studies have revealed that organizational commitment is greater for those individuals whose leader supports them to participate in the decision-making process (Rhodes and Steers 1981), deals them carefully (Bycio et al. 1995) and shows fairness (Allen and Meyer 1990).

Previous leadership studies have observed this relationship by opting different mediators including employee voice (Avey et al. 2012); role clarity (Newman et al. 2015); loyalty to a supervisor (Okan and Akyüz 2015); and organizational politics (Kacmar et al. 2013). Psychological empowerment can be defined as an inspirational factor which puts emphasis on the perceptions of the follower being empowered (Menon 2001; Spreitzer 1995a) and plays a significant role in enhancing employees’ performance and work attitudes (Koberg et al. 1999; Menon 2001; Spreitzer et al. 1997). Several types of research demonstrate the effects of psychological empowerment on leadership mainly focusing on organizational culture, structure, personality traits and climate (Koberg et al. 1999; Sigler and Pearson 2000; Spreitzer 1995a). In a similar vein, Zhu (2008) underlined psychological empowerment as a potential mediator of ethical leadership in relation to employee moral identity. As a result, employees with higher empowerment in a sense of influence, autonomy, value, and competency are more likely to feel satisfied with their supervisor and job and are more committed to their organization. We, therefore, propose that the effect of ethical leadership on follower’s attitudes via psychological empowerment plays important role in the organization.

In recent years, the ethical scandals involving government employees have highlighted the need for more research on ethical leadership in the public sector. For example, in the United States, in 2018, Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey found that about 45% of government employees do not believe the leaders in their organization in maintaining high standards of honesty and integrity while 34% do not feel that they can disclose a suspected violation of laws or regulations without fear of reprisal (OPM 2018). It is unclear as to whether the research on ethical leadership of public sector employees in emerging economies such as China which have a collectivistic culture is different from the western nations. Hence, we choose public organizations for conducting this research rather than the private sector.

Taken together, we seek the following contributions to the literature by answering the calls by researchers to explore the differentials effects of psychological empowerment on subordinate responses to the leadership behavior of their supervisors that vary from country to country (Chen 2017; Jordan et al. 2017; Namasivayam et al. 2014). We further explicate the underlying process of how ethical leadership works through four-dimensional psychological empowerment to promote employees’ behaviors. The current study enriches the existing research on ethical leadership by identifying the contexts under which ethical leadership might have a different effect on employee-related outcomes. Although, some of these relationships have been studied individually in different contexts by other leadership styles (Puni et al. 2018; Ribeiro et al. 2018), present work demonstrates the complete process of how ethical leadership is associated with organizational outcomes, which has not been previously investigated in the context of Chinese workplace and the testing of these relationships via a mediated approach is relatively new. This should enable us to advise managers in the Chinese public sector as to what strategies may be utilized d to foster high levels of organizational commitment and enhance job satisfaction amongst their employees.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Following this introduction, the first section explains the conceptual framework and the existing literature review for analyzing the effects of ethical leadership on subordinate behaviors. The methodology employed in the study is presented in the second section. Different data techniques opted to analyze the proposed relationships along with results are then be discussed. Finally, the paper concludes the main findings, limitations, and implications of the study.

1.1 Theory and hypotheses

1.1.1 Ethical leadership

Integrity, fairness, and honesty have been considered as the key elements of leadership effectiveness in both public and private sector organizations (Kouzes and Posner 1992). Since past decade, the adaptation of systematic approaches to illustrate and examine the meanings of ethical leadership and its consequences has been given more attention (Fehr et al. 2015; Hassan et al. 2014).

Basically, ethical leadership has been discussed in different senses. Kanungo (2001) observed that ethical leaders involve in particular behaviors that are beneficial and appreciated by their followers and they integrate moral norms into certain values and beliefs in public organizations (Khuntia and Suar 2004) but Brown et al. (2005) identified that ethical leaders keenly promote moral behaviors among their subordinates, provide ethical guidance, clearly communicate ethical standards and provide a clear sense of accountability towards ethical and unethical conduct.

On the other hand, many scholars seek to describe how some leaders successfully tackle the complex situations in organizations to meet the expectations for both legal and ethical standards. Hence, ethical leadership involves in both traits and manners of the leader (such as honesty, well caring, fair decision making, etc.) and also engaged in moral aspects that encourage employees’ ethical behaviors along with offering rewards and punishment with respect to their behavior. Ethical leaders are legitimate and credible role models for their subordinates, exhibit appropriate behaviors and treat their followers with respect and consideration (Brown and Treviño 2006).

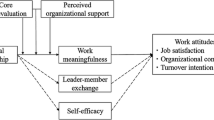

Although leadership has long been studied regarding ethics (Barnard 1938) however in the last decade ethical leadership is considered as a distinct type of leadership (Brown et al. 2005). The recent increase in ethical leadership research proves its usefulness and application in different ways. For instance, ethical leadership has a positive relation with the leader’s integrity, idealized influence, consideration and fairness (Miao et al. 2013; Okan and Akyüz 2015). Consistent with Brown et al. (2005), ethical leadership prophesies some of employees’ job outcomes such as leader’s effectiveness, satisfaction, keenness to put extra job effort and more importantly willingness to report ethical problems while Neubert et al. (2009) confirmed that ethical leadership along with interactional justice promotes followers’ perceptions towards ethical climate. The main concern of previous studies has been only to examine the direct effect of ethical leadership with only a couple of researches investigate different mechanisms that connect ethical behaviors with employee outcomes such as psychological empowerment (Avey et al. 2012). Therefore, in this paper, we develop a theoretical and empirical mechanism to explore the mediating effect associated with several ethical leadership outcomes (Fig. 1).

1.1.2 Effect of ethical leadership on affective commitment and job satisfaction

Besides a willingness to report unethical conduct of employees, ethical leadership can affect followers’ attitudes and behaviors in a positive way. As Brown et al. (2005) advocated that ethical leaders have a certain impact on employees’ commitment to their organization. Generally, commitment refers to the degree of employees’ involvement, identification and emotional attachment with the organization (Meyer and Allen 1991) as it exhibits allegiance with organizational values as well as inner satisfaction (Meyer and Allen 1991). Furthermore, organizational commitment is as important as it reduces employees’ turnover intention enhances work performance as well as organizational citizenship behavior (Meyer et al. 2002).

As stated ethical leadership can influence employees’ commitment toward their job in public organizations (Blau 1964) and the relationship between ethical leaders and subordinates become strong under social exchanges rather than economic; as these exchanges concern with reciprocal affection and trust while economic exchanges are impersonal in nature (Brown and Treviño 2006). Ethical leaders can establish a better relationship as they are more trustworthy, take much care of subordinates and make fair decisions. Through this way, they enhance more loyalty and commitment among employees. In line with these predictions, some recent studies (Babalola et al. 2016a; Lam et al. 2016; Lin et al. 2017) confirmed a strong association between ethical leadership and employees’ intention to stay in public sector organizations.

Leaders have the power to influence followers’ attitudes towards job (Yukl 2013). Leaders with high standard ethical conducts do so by the way of manifesting personal behavior and sharing moral values (Brown and Mitchell 2010). Prior research provides strong evidence of the relationship between ethical leadership and followers’ satisfaction with their leaders (Guchait et al. 2016) and is confirmed by (Neubert et al. 2009) with three aspects.

First, ethical leaders are considered role models among followers due to their credibility, integrity, and care for employee well-being (Stouten et al. 2012). They also provide them feedback opportunities and enhance job autonomy and task significance insights (Piccolo et al. 2010). These attributes make their personality more valuable and attractive (Brown and Treviño 2006). According to Dirks and Ferrin (2002) and Kacmar et al. (2011) employees who receive greater respect, support and consideration from their leaders feel more obliged in reciprocating positive attitudes such as job satisfaction.

Second, while making important decisions related to designing the job, performance evaluation and promotional activities, ethical leaders treat employees fairly (Brown and Treviño 2006). These behaviors and attributes provoke trust and enthusiasm among employees and also known as major contributors to job satisfaction (Engelbrecht et al. 2017; Ko et al. 2018; Newman et al. 2014).

Third, ethical leadership is studied as a continuous process of moralization by which followers assign moral weight to the behavioral activities of their leaders and this can happen only if leader’s actions are associated with relevant moral foundations of employees (Fehr et al. 2015). As Brown and Mitchell (2010) found value congruence to illustrate the influence of various ethical components associated with charismatic leadership on workplace deviance. In this way, charismatic leaders effectively generate value congruence between themselves and subordinates by employing existing values or developing new values (Brown and Treviño 2009) and promotes job satisfaction in the workplace (Shamir et al. 1998). Based on the above discussion we predict:

H1

There will be a significant and positive relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment.

H2

There will be a significant and positive relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction.

1.1.3 Effect of psychological empowerment on affective commitment and job satisfaction

Different approaches of empowerment have caused in several ambiguities regarding the specific type of the empowerment concepts. According to Menon (2001) empowerment can be distinguished from a structural empowerment approach to a motivational empowerment approach. Structural empowerment approach involves in bestowing the power or authority of decision making to other organizational members (Thorlakson and Murray 1996). Earlier, this approach is considered as a traditional approach since it emphasizes the actions of the power holding personnel who delegates some extent of autonomy to their subordinates having inadequate authority.

On the other hand, the motivational approach is incorporated as psychologically enabled empowerment and it emphasizes on the cognition of the employees who have some influence or authority; in other words, individual’s psychological state or the internal process (Liu et al. 2017). Numerous studies have demonstrated that employees’ level of perception positively mediates the relationship between worker’s performance and management activities (Behling and McFillen 1996; Mccann et al. 2006). This resulted in developing a better research awareness in basic cognitive as well as psychological states of motivational empowerment approach. Such kind of empowerment approach was also discussed by Conger and Kanungo (1988), who outlined it as an efficient process of enhancing the emotions of individuals towards self-efficacy. In accordance with Bandura (1989), self-efficacy comprises individual’s beliefs with capabilities or competencies to drive the cognitive resources, set of actions and inner motivation required to meet particular situational demands.

Based on the research of Conger and Kanungo (1998), another study is presented by Thomas and Velthouse (1990) with more complicated cognitive empowerment model in which self-efficacy is considered the only one factor of individual’s experience about empowerment. In accordance with these researchers, empowerment is based on changes in four cognitive factors which are used to shape employee motivational levels: impact (in a sense of individuals believes to enthuse others at work), self-determination (in other words autonomy or having choice or power to initiate and regulate actions), meaning (the value of worker’s goal achievement with relation to predetermined standards or criterions) and competency (identical with Conger and Kanungo’s views about self-efficacy). The term ‘psychological empowerment’ was Initially coined by Spreitzer (1995a) who defined it as intensified intrinsic motivation, derived from four cognitive factors pre-discussed by Thomas and Velthouse (1990).

All certain cognitive states associated with psychological empowerment has a significant and positive relationship with employees’ affective organizational commitment (Sigler 1997). Affective commitment normally reflects a greater relationship between employees and the organization as compared to normative and continuance commitment since continuance commitment mostly deals with financial needs of individuals and normative commitment focuses on essential behaviors of employees use to stay committed with the organization (Koberg et al. 1999; Meyer and Allen 1991).

Mento et al. (1980) claimed that a sense of having value in the job highly contributes toward affective commitment and the theoretical background of this relationship is also examined by different theorists (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). These relationships are changed into trust, loyalty and mutual concerns over the time and it is possible only if both leader and subordinate follow certain norms and rules particularly reciprocity norm which is related to cultural obligation. Reciprocity norm is described by Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005) as “a norm that explains how one should behave and those who follow these norms are obligated to behave reciprocally” (p. 877). Most exchange relationships are founded when leaders provide full support to their followers and take much care of them. Furthermore, these relationships lead to valuable work behaviors likes commitment to the organization (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

Several researchers have demonstrated that empowerment stimulates employees’ work attitudes including employees’ job satisfaction and commitment (Esmaeilifar et al. 2018; Liden et al. 2000; Spreitzer 1995b). Job satisfaction is also considered as a sequel of psychological empowerment (Seibert et al. 2004; Spreitzer et al. 1997) while some recent studies confirm positive relationship and strong correlations between job satisfaction and all four aspects of psychological empowerment (Aydogmus et al. 2017; Barroso Castro et al. 2008; Boamah et al. 2017; Jordan et al. 2017).

The worth of a suitable job for an individual’s satisfaction has been discussed by theorists (Hackman and Oldham 1980). They argued that employees with higher perception towards their work feel higher job satisfaction than employees who feel their jobs less valuable. This theory further reveals that employees with high confidence towards their success are much happier than employees who have low confidence level and also have fear to fail (Martinko and Gardner 1982). Value and decision-making autonomy provide a sense of control to employees over their jobs resulting in more satisfaction as they have high motivation to do more work by themselves than to other workers (Thomas and Tymon 1994). Ashforth (1989)argues that employees who have a direct impact and involvement in the outcomes of an organization have greater job satisfaction. With the help of these arguments, it could be assumed that psychological empowerment has a significant effect on job satisfaction and affective commitment to the organization in presence of reciprocation. Based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence we predict:

H3

There will be a significant and positive relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment.

H4

There will be a significant and positive relationship between psychological empowerment and job satisfaction.

1.1.4 Mediating effect of psychological empowerment

The theoretical evidence of psychological empowerment related to employees’ attitudes is relatively based on employees’ needs that are fulfilled by getting more empowered. As mentioned earlier, ethical leaders are likely to foster psychological empowerment in a sense of fairness, equity and accountability in dealings with their followers and expect similar behaviors from them.

According to Liden et al. (2000), psychological empowerment is considered as the key element that distinguishes ethical leadership behaviors from other leadership styles. It involves delegating the responsibilities to subordinates and also enhances their abilities to believe in themselves in generating creative and unique ideas. Ethical leaders give more importance to proactivity and self-determination of their subordinates in a way of more empowerment rather than control (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009).

Ethical leaders formulate ultimate objectives that provide a sense of empowerment and serve to motivate employees who engaged with these objectives (Kanungo and Mendonca 1996). As stated by Burke (1986) leaders inspire and empower their subordinates through the provision of clear direction towards worthwhile and meaningful purpose whereas ethical leaders empower subordinates by provoking enthusiasm towards goal achievement and by providing challenge and value in their work (Menon 2001; Yukl and Van Fleet 1992).

Along with the communication of inspirational and valuable goals, ethical leaders also prefer several cognitive states related to empowerment by articulating self-confidence with their capabilities to convey and achieve high work performance at work (Burke 1986; Shamir et al. 1998). Such inspiring enthusiasm increases perceived competency (Menon 2001) and self-efficacy level (Conger and Kanungo 1988)—both of them are critical and essential for psychological empowerment. Thomas and Velthouse (1990) confirmed that empowerment plays an important role in improving more concentration, creativity, resilience, satisfaction and greater commitment to the organization among employees. Numerous studies have found a positive association among ethical leadership and all dimensions empowerment relevant to employees’ outcomes (Avey et al. 2011, 2012; Bouckenooghe et al. 2015; Zhu 2008).

Similarly, Avolio et al. (2004) and Aydogmus et al. (2017) found a complete mediating influence of psychological empowerment between transformational leadership and employees’ commitment and job satisfaction respectively while Huang et al. (2006) found partial mediation in their study of participative leadership. Seibert et al. (2004) confirmed the mediating effect of psychological empowerment (PE) between empowering climate and job performance. Furthermore, Zhu (2008) and Dust et al. (2018) used psychological empowerment as a potential mediator between ethical leadership and employee moral identity and employee success. Based on the above evidence we suppose:

H5

The relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment will be positively mediated by psychological empowerment.

H6

The relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction among employees will be positively mediated by psychological empowerment.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and procedure

The data for the present research was obtained through a structured questionnaire from government employees working in various public sector organizations in China. Based on the recommendations of Brislin (1993) the original survey questionnaire was translated from English to the Chinese language before distribution. To avoid any ambiguity, all participants were communicated directly instead of their organization and their secrecy was also assured. From the database of the Zhejiang University of China, 1000 alumni who obtained their Master of Public Administration degree from School of Public Affairs were contacted through email to take part in this study. After their participation desirability, an online survey link was sent to them in three separate waves in 8 weeks gap from November to December 2016. These steps were taken to reduce common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). In the first wave, employees were asked to provide their demographic (including control variables e.g. age, gender, education, tenure) details and rate ethical leadership behavior of their current supervisor. In second wave data on psychological empowerment was obtained while in the third wave they evaluated employees’ work attitudes such as commitment to organization and job satisfaction. In order to reduce the impact of common method bias, which may arise due to a common method utilized for data collection, Harman’s one-factor test was conducted. The highest variance explained for all the three constructs was 37.84% (approx. 38%), indicating no common method bias in our results. In addition, to capture the common variance among all the hypothesized constructs, the common latent factor (CLF) test was conducted as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003).

A total number of 467 employees responded to surveys conducted in all three waves with the response rate of 46.7% approximately. Male participants were 62.3% in total while 57.4% of employees were in leadership positions. About 92.6% of employees having age < 40 years and 75% of them had been working for < 5 years under their current supervisor.

2.2 Measures

Ethical leadership: Ethical leadership was measured by using 10-items ELS developed by Brown et al. (2005). Followers were required to evaluate supervisor’s behavior using 5-point Likert type scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. The validity of this scale is widely proved in several studies across the globe (Engelbrecht et al. 2017; Ko et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2017). Example item for this study included: “My supervisor conducts his/her personal life in an ethical manner”. The Cronbach’s alpha is noted 0.93 for this scale.

Psychological empowerment: The evaluation of psychological empowerment was based on a 12-items four-dimensional empowerment scale developed by Spreitzer (1995b). This scale is widely adopted in recent studies (Ahmad and Gao 2018; Dust et al. 2018). All items were rated by a five-point Likert scale where 5 is for “strongly agree” and 1 is for “strongly disagree”. Example questions for each of four dimensions are: “My job activities are personally meaningful to me” (meaning or value), “I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job” (self-determination or autonomy), “I have significant influence over what happens in my department” (impact or influence) and “I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities” (competency). Individual reliability of each dimension ranged from 0.78 to 0.87. Overall Cronbach’s alpha for psychological empowerment is 0.83.

Affective commitment: Affective commitment was measured by using a 6-items scale established by Meyer et al. (1993). This scale is widely used in several studies and valid for measuring the required results (Dawson et al. 2015; Dhar 2015). Employees were asked to evaluate affective commitment on a 5-point Likert scale where (“1 = strongly disagree”) and (“5 = strongly agree”). A sample question is: “I would be happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.” Cronbach’s alpha for affective commitment scale is 0.93.

job satisfaction: Cammann et al.’s (1983) 3-item measurement scale was used to evaluate job satisfaction in this study. Harari et al. (2018) and Guchait et al. (2016) validated this scale in their studies. Employees were solicited to rate their level of job satisfaction by using a 5-point Likert type scale (where 5 shows “strongly agree” and 1 shows “strongly disagree”). A sample item is: “all in all, I am satisfied with my job”. Cronbach’s Alpha is noted 0.86 for this scale.

2.3 Control variables

This study contains four control variables including; gender, age, education and tenure. We measured for employees’ gender as (1 = “male” and 0 = “female”), age is measured through categorical variables as (1 = “21–25 years”, 2 = “26–30 years”, 3 = “31–35 years”, 4 = “36–40 years”, 5 = “41–45 years”, 6 = “46–50 years”, 7 = “51–55 years”, 8 = “56–60 years”), education as (1 = “masters” and 2 = “doctoral”) and working tenure with current supervisor is measured by following categories (1 = “1–2 years”, 2 = “3–5 years”, 3 = “6–10 years”, 4 = “11–13 years”, 5 = “14–17 years”, and 6 = “18–20 years”).

2.4 Data analysis and results

For analyzing data and results SPSS and AMOS 23.0 were used as a statistical tool. Descriptive statistics, means, standard deviations (SD) and Pearson’s correlations of all variables are shown in Table 1. The results show significant and positive correlations among all the presumed constructs. Based on exploratory factor analysis of ethical leadership we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and used the maximum likelihood estimate. Goodness of fit indices of CFA results are presented in Table 2 where the values of Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.908, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.038, Normed Fit Index (NFI) = 0.924, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.031, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.985, Relative Fit Index (RFI) = 0.909, Incremental Fit Measures (IFI) = 0.985 and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.982. All these values surpassed the good fit criteria in which Bentler and Bonett (1980) suggested χ2/d.f. should not exceed 3, while estimates for NFI and CFI should be equal or above 0.9 for a good fit. Regarding the estimates for GFI and AGFI, Seyal et al. (2002) and Dhar (2016) suggested estimates above the recommended value of 0.8 as a good fit.

The convergent validity of the variables was evaluated by examining the factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliabilities (CR) which are shown in Table 3. The composite reliabilities ensured the minimum cutoff at 0.60 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988), while the estimates for the AVE crossed the threshold of 0.50 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). As per the recommendations of Hair (2010), factor loadings above 0.5 are considered significant, thus the loadings provided a significant contribution for each construct. Hence, the measures did not have any issue regarding the convergent validity. As shown in Table 3, Cronbach’s α were all above 0.70 (Nunnally and Bernstein 2010), representing higher internal consistency and validity of the constructs.

To check the discriminant validity, AVE estimates were compared with the squared values of correlation between the constructs. As shown in Table 4, all the AVE values were greater than the squared correlations, thus the model fits the criteria for discriminant validity (Shaffer et al. 2016). Measurement models (Table 5(a) and (b)) further validate construct validity as recommended by Barroso Castro et al. (2008).

2.5 Hypothesis testing

In order to test the hypotheses, we used a full structural equation model using maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS software. Although hypotheses 1–4 are confirmed through correlations (shown in Table 1) as well as regression coefficients (shown in Table 6). Since hypothesis 1 predicted there will be a significant and positive relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment. As evident in Tables 1 and 6, we found support for Hypothesis 1 (standardized β = 0.43, t = 8.43, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 2 predicted there will be a significant and positive relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction. We found support for Hypothesis 2 (standardized β = 0.33, t = 6.88, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 3 predicted there will be a significant and positive relationship between psychological empowerment and affective commitment. We found support for Hypothesis 3 (standardized β = 0.51, t = 9.62, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 4 predicted there will be a significant and positive relationship between psychological empowerment and job satisfaction. As evidenced in Table 6 we found support for Hypothesis 4 (standardized β = 0.39, t = 8.13, p < 0.01).

For testing Hypotheses 5 and 6 which are about the mediation effects of psychological empowerment between ethical leadership and affective commitment and job satisfaction, we choose two procedures recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986) and James et al. (2006).

Baron and Kenny’s (1986) research concerned with regression weights and correlation of studied variable and for full mediation support four criterion should be met. First, the independent variable (ethical leadership) should have a significant relationship with a mediator (psychological empowerment). Second, ethical leadership should have a significant relationship with dependent variables (affective commitment and job satisfaction). Third, the mediator should be significantly related to dependent variables. Finally, the direct relationship between independent variables and dependent variables must be insignificant in the presence of a mediator in the regression equation.

Although the mediation for the present study is proved with the help of Baron and Kenny’s recommendations yet James and Brett (1984) suggested to adopt confirmatory approaches like structural equation modeling (SEM) to test mediation as Baron and Kenny’s (1986) model is believed as theoretical or contributory mediation model. The basic difference between SEM techniques and Baron and Kenny’s method is that SEM uses a parsimonious principle for full mediation while Baron and Kenny’s technique is used for partial mediation only.

Furthermore, James et al. (2006) have suggested another two-step approach to test mediation. Actually, this approach is also based on SEM and Baron and Kenny’s strategy. First, it should be confirmed whether hypothesized mediation is partial or full. For this purpose, previous studies and theories are hoped to provide a sufficient base-line in determining partial or full mediation. If these theories or studies provide insufficient evidence for partial or full mediation then it is recommended to choose a parsimonious model to test full mediation as it can be rejected easily in sciences (Mulaik 2001).

Secondly, when the mediation is confirmed then it is suggested to test it using structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. With the recommendations of Wang et al. (2005), we made four nested models and compare them (as shown in Table 7).

Model (A) is a hypothesized one having direct paths from ethical leadership (independent variable) to employees’ affective commitment and job satisfaction (dependent variables). Besides, this model is compared with three other models. Model (B) integrated no direct path from ethical leadership to outcome variables, Model (C) integrated a direct path from ethical leadership to job satisfaction, and Model (D) integrated direct path of ethical leadership to affective commitment. It is shown in Table 7 that Chi square difference is not significant while comparing the hypothesized model (A) to all other models. This provides that Model (A) is the best-fitted model and evidence of mediation.

Moreover, Fig. 2 illustrates the SEM results where path from ethical leadership to psychological empowerment is significant (β = 0.39; p < 0.01) while paths from psychological empowerment to affective commitment (β = 0.63; p < 0.01) and to job satisfaction (β = 0.43; p < 0.01) are also significant and shows positive and strong relationships. It is evident from Fig. 2 that the direct path from ethical leadership to affective commitment (β = 0.13, p > 0.05) is insignificant and confirms full mediation while the direct path from ethical leadership to job satisfaction (β = 0.19, p < 0.05) is significant and proves partial mediation.

In line with the above evidence, we performed percentile bootstrapping and bias-corrected bootstrapping at 95% confidence interval with 5000 bootstrap sample (Arnold et al. 2015) to test full or partial mediation. We calculated the confidence of interval of the lower and upper bounds to test the significance of indirect effects as recommended by Preacher and Hayes (2008). As seen in Table 8, we found that the indirect effects of psychological empowerment on affective commitment (standardized β = 0.25, p < 0.01, Z = 5.03) and job satisfaction (standardized β = 0.17, p < 0.01, Z = 3.42) are significant. The direct relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment (β = 0.13, p = 0.33 and Z = 1.63) is not significant and supported Hypothesis 5 with full mediation and the direct relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction (β = 0.10, p < 0.05 and Z = 2.72) is significant and supported Hypothesis 6 with partial mediation.

3 Discussion

The main aim of this research was to investigate the theoretical and empirical relationships between ethical leadership and employees’ work-related attitudes with respect to affective commitment and job satisfaction in the presence of psychological empowerment as a mediator among Chinese public sector employees. Our findings also confirm previous studies in which mediating mechanisms of psychological empowerment between ethical leadership and employees’ work attitudes were explored (Dust et al. 2018; Zhu 2008). It has been confirmed that employees who have inspirational feelings towards an attractive goal and experiencing a sense of control (influence and worth) possess a higher level of job satisfaction and commitment to the organization. These facts identify positive links between psychological empowerment and followers’ job satisfaction and commitment (Aydogmus et al. 2017; Chen 2017; Jordan et al. 2017). Employees with greater insight of empowerment in a sense of influence, self-determination, value, and self-efficacy are more satisfied and committed to their organization.

The mediating effect of psychological empowerment on the relationship between ethical leadership and employees work attitudes is our main finding. Leaders who want to improve commitment and job satisfaction among employees must be capable to communicate eagerness towards organizational objectives and create a sense of perceived control in terms of self-determination and self-efficacy.

Prior research has found that how ethical leaders provide meaning to employees’ work by developing inspirational goals and getting their attention towards the attainment of those objectives (Wang et al. 2017). Additionally, these leaders inspire employees’ feeling for competency, influence, meaningfulness, and self-determination by emotional attachment (Avey et al. 2012; Zhu 2008). However, leaders also have supportive behaviors that are related to different cognitive states of psychological empowerment especially with perceived control (Avolio et al. 2004). Employees who have a perception of empowerment (with a strong sense of control and energy with respect to their jobs) feel more effectively committed to the organization that brings them this sense of power.

3.1 Theoretical implications

Findings of our study suggest some important theoretical implications for ethical leadership literature. First, by examining the mediating role of psychological empowerment in the association between ethical leadership and followers’ attitudes (affective commitment and job satisfaction), our study contributes to better understanding of the underlying mechanism through which ethical leadership relates to these attitudes. The findings of our study identify that leaders boost the employees feeling of psychological empowerment by exhibiting ethical leadership behaviors, which ultimately leads to enhanced satisfaction level and organizational commitment in them. Our findings confirm the existing evidence which suggested that employee psychological empowerment serves as an important motivational resource which enables employees to be extra committed and satisfied with their work (Aydogmus et al. 2017; Chen 2017). Moreover, examining employee psychological empowerment as a mediator helps us better understand how and why ethical leadership can enhance employee work behaviors.

Secondly, this study was conducted in a developing country “China” which is a collectivistic nation and have the different political and cultural environment as compared to other Asian and western nations and is a very unique area for this research. To date, very few empirical studies have examined ethical leadership behavior and its effects on employee outcomes in the Chinese context. Interestingly, the results from this study posit that ethical leadership can be effective in organizations within a country having such a unique environment. These findings show that ethical leadership can be beneficial across different cultures.

3.2 Practical implication

This research also has a number of practical implications. First, our study confirmed that ethical leadership is effective in enhancing employees’ job satisfaction level and commitment to their organization, which also suggests that ethical leadership role is crucial in providing proper guideline by which employees feel more encouraged to involve in their work.

Second, as this study demonstrates that ethical leadership has the indirect effect on follower outcomes in the presentence of psychological empowerment, therefore, it is proposed that organizations and leaders should establish such conditions through which they are able to enhance followers’ perceptions of psychological empowerment. Provided that, we recommend that organizations should design empowerment training programs to help the employees exhibit their maximum potential (Ahmad and Gao 2018).

Third, as ethical leadership has positive influences on follower outcomes, therefore, organizations need to promote moral behaviors both in subordinates and their supervisor. For example, organizations can hire and develop those leaders who have a sense of ethical conducts in their vision. The organizations can also invest in management training programs focusing on both leaders’ and employees’ ethical behavior (Babalola et al. 2016b).

Another possible way to encourage ethical behavior among employees in the organizations can be through making it part of the in-role job requirement. When the display of such behaviors is formally rewardable or punishable, employees (both leaders and subordinates) will feel more obligated to perform them. In short, though having ethical leadership in organizations is not an easy task (Den Hartog 2015), organizations need to provide education to their employees, especially top-order leadership and supervisors about the worth of ethical behavior in the organization to get positive organizational outcomes.

3.3 Study limitations and suggestions for future research

As with all research the findings of present research need to be viewed in light of its limitations. First, the data used for this study collected from a single source and may cause the possibility of common method bias (CMB) (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Even we also followed the recommendations of Podsakoff et al. (2003) for overcoming the possibility of CMB by administering the survey in three different waves, assuring confidentiality of responses and randomly ordering the items within each survey. We also performed Harman’s single factor test and common latent factor (CLF) technique to confirm that CMB had not significantly affected the results of the study. We do, however, acknowledge that in order to definitively rule out the potential problems caused by CMB, future research should utilize other rated measures of employee behaviors.

Second, since our study respondents were public sector employees of China, there would be worth in future research validating whether these findings are generalizable to other industrial and cultural contexts. More specifically, comparative research would be valuable that is being conducted in western nations, which are less relationship oriented and more individualistic than the Chinese culture, to estimate to what extent the findings of the present study are culturally influenced.

Third, the fact that study participants were recruited from an alumni database brings into question the extent to which their views represent those of others in the organization’s participants were employed in. However, given the sensitive setting of our research, the Chinese public sector, and the sensitive nature of the questions related to ethical leadership and psychological empowerment, we feel contacting the participants directly allowed us to reduce social desirability bias, given the organizations in which the participants were employed were not involved in the process of data collection.

Finally, although the focus of our study was on ethical leadership, we might also expect psychological empowerment to accentuate the positive influence of other leadership styles such as entrepreneurial and authentic leadership (Renko et al. 2015) on employee attitudes, given that such leadership styles also engage supervisors’ role modeling expected behavior and would be another interesting and fruitful area for future research.

4 Conclusion

To conclude, this paper examined the relationship between ethical leadership and employees’ affective commitment and job satisfaction, and the mediating role of psychological empowerment. We found that psychological empowerment strongly mediated the impact of ethical leadership on affective commitment and partially mediated the relationship with employees’ job satisfaction. By the way of empowering followers, ethical leaders may enhance their level of satisfaction and greater commitment to the organization. Taken together, these findings provide greater insight into ethical leadership research and suggest several steps by which ethical behaviors can be promoted in public organizations. Although our study is limited, we hope it will provide a strong baseline for future research.

References

Ahmad I, Gao Y (2018) Ethical leadership and work engagement: the roles of psychological empowerment and power distance orientation. Manage Decis 56(9):1991–2005. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-02-2017-0107

Allen NJ, Meyer JP (1990) The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Organ Psychol 63:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

Arnold KA, Connelly CE, Walsh MM, Martin Ginis KA (2015) Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. J Occup Health Psychol 20:481

Aronson E (2001) Integrating leadership styles and ethical perspectives. Can J Adm Sci/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration 18:244–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2001.tb00260.x

Ashforth BE (1989) The experience of powerlessness in organizations. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 43:207–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90051-4

Avey JB, Palanski ME, Walumbwa FO (2011) When leadership goes unnoticed: the moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. J Bus Ethics 98:573–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0610-2

Avey JB, Wernsing TS, Palanski ME (2012) Exploring the process of ethical leadership: the mediating role of employee voice and psychological ownership. J Bus Ethics 107:21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1298-2

Avolio BJ, Gardner WL (2005) Authentic leadership development: getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Leadersh Q 16:315–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.001

Avolio BJ, Zhu W, Koh W, Bhatia P (2004) Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. J Organ Behav 25:951–968. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.283

Aydogmus C, Camgoz SM, Ergeneli A, Ekmekci OT (2017) Perceptions of transformational leadership and job satisfaction: the roles of personality traits and psychological empowerment. J Manage Organ. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2016.59

Babalola MT, Stouten J, Euwema M (2016a) Frequent change and turnover intention: the moderating role of ethical leadership. J Bus Ethics 134:311–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2433-z

Babalola MT, Stouten J, Euwema MC, Ovadje F (2016b) The relation between ethical leadership and workplace conflicts: the mediating role of employee resolution efficacy. J Manage. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316638163

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16:74–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/009207038801600107

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44:1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.9.1175

Barnard CI (1938) The functions of the executive. Harvard University, Cambridge

Baron RM, Kenny DA (1986) The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 51:1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Barroso Castro C, Villegas Perinan MM, Casillas Bueno JC (2008) Transformational leadership and followers’ attitudes: the mediating role of psychological empowerment The. Int J Human Resource Manage 19:1842–1863. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802324601

Bass BM (1985) Leadership and performance beyond expectations. Collier Macmillian, London

Bass BM, Steidlmeier P (1999) Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadersh Q 10:181–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1048-9843(99)00016-8

Behling O, McFillen JM (1996) A syncretical model of charismatic/transformational leadership. Group Organ Manage 21:163–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601196212004

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88:588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. Transaction Publishers, Piscataway. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203792643

Boamah SA, Read EA, Spence Laschinger HK (2017) Factors influencing new graduate nurse burnout development, job satisfaction and patient care quality: a time-lagged study. J Adv Nurs 73:1182–1195. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13215

Bouckenooghe D, Zafar A, Raja U (2015) How ethical leadership shapes employees’ job performance: the mediating roles of goal congruence and psychological capital. J Bus Ethics 129:251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2162-3

Brislin RW (1993) Understanding culture’s influence on behavior. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers, San Diego. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368829302400206

Brown ME, Mitchell MS (2010) Ethical and unethical leadership: exploring new avenues for future research. Bus Ethics Q 20:583–616. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq201020439

Brown ME, Treviño LK (2006) Ethical leadership: a review and future directions. Leadersh Q 17:595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown ME, Treviño LK (2009) Leader–follower values congruence: are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? J Appl Psychol 94:478–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014069

Brown ME, Treviño LK, Harrison DA (2005) Ethical leadership: a social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 97:117–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Burke W (1986) Leadership as empowering others. Executive Power. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957848.n8

Bycio P, Hackett RD, Allen JS (1995) Further assessments of Bass’s (1985) conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership. J Appl Psychol 80:468–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.4.468

Cammann C, Fichman M, Jenkins GD, Klesh J (1983) Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members. In: Seashore SE, Lawler EE III, Mirvis PH, Cammann C (eds) Assessing organizational change: a guide to methods, measures, and practices. Wiley, New York. https://doi.org/10.1177/017084068400500420

Chen HW (2017) An empirical analysis of the influence of civil servants’ psychological empowerment and job satisfaction on organizational citizenship behavior for the environment. http://doi.org/10.1108/md-09-2018-0966

Ciulla JB (2014) Ethics, the heart of leadership. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara

Conger JA, Kanungo RN (1988) The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Acad Manage Rev 13:471–482. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1988.4306983

Conger JA, Kanungo RN (1998) Charismatic leadership in organizations. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Cropanzano R, Mitchell MS (2005) Social exchange theory: an interdisciplinary review. J Manage 31:874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

Dawson A, Sharma P, Irving PG, Marcus J, Chirico F (2015) Predictors of later-generation family members’ commitment to family enterprises. Entrep Theory Pract 39:545–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12052

Den Hartog DN (2015) Ethical leadership. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 2:409–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111237

Dhar RL (2015) Service quality and the training of employees: the mediating role of organizational commitment. Tour Manage 46:419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.001

Dhar RL (2016) Ethical leadership and its impact on service innovative behavior: the role of LMX and job autonomy. Tour Manage 57:139–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.011

Dirks KT, Ferrin DL (2002) Trust in leadership: meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. American Psychological Association, Worcester

Dust SB, Resick CJ, Margolis JA, Mawritz MB, Greenbaum RL (2018) Ethical leadership and employee success: examining the roles of psychological empowerment and emotional exhaustion. Leadersh Q. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.02.002

Eby LT, Freeman DM, Rush MC, Lance CE (1999) Motivational bases of affective organizational commitment: a partial test of an integrative theoretical model. J Occup Organ Psychol 72:463–483. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317999166798

Engelbrecht AS, Heine G, Mahembe B (2017) Integrity, ethical leadership, trust and work engagement. Leadersh Organ Dev J 38:368–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-11-2015-0237

Esmaeilifar R, Iranmanesh M, Shafiei MWM, Hyun SS (2018) Effects of low carbon waste practices on job satisfaction of site managers through job stress. RMS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0288-x

Fehr R, Yam KCS, Dang C (2015) Moralized leadership: the construction and consequences of ethical leader perceptions. Acad Manage Rev 40:182–209. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2013.0358

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Grojean MW, Resick CJ, Dickson MW, Smith DB (2004) Leaders, values, and organizational climate: examining leadership strategies for establishing an organizational climate regarding ethics. J Bus Ethics 55:223–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-1275-5

Guchait P, Simons T, Pasamehmetoglu A (2016) Error recovery performance: the impact of leader behavioral integrity and job satisfaction. Cornell Hosp Q 57:150–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965515613858

Hackman JR, Oldham GR (1980) Work redesign. Addison-Wesley, Boston

Hair JF (2010) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-04898-2_395

Harari MB, Thompson AH, Viswesvaran C (2018) Extraversion and job satisfaction: the role of trait bandwidth and the moderating effect of status goal attainment. Personal Individ Differ 123:14–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.041

Hassan S, Wright BE, Yukl G (2014) Does ethical leadership matter in government? Effects on organizational commitment, absenteeism, and willingness to report ethical problems. Pub Adm Rev 74:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12216

House RJ (1976) A 1976 theory of charismatic leadership. Working paper series 76-06:1–38. http://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(93)90041-q

Huang X, Shi K, Zhang Z, Cheung YL (2006) The impact of participative leadership behavior on psychological empowerment and organizational commitment in Chinese state-owned enterprises: the moderating role of organizational tenure. Asia Pac J Manage 23:345–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-9006-3

James LR, Brett JM (1984) Mediators, moderators, and tests for mediation. J Appl Psychol 69:307–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.307

James LR, Mulaik SA, Brett JM (2006) A tale of two methods. Organ Res Methods 9:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105285144

Jordan G, Miglič G, Todorović I, Marič M (2017) Psychological empowerment, job satisfaction and organizational commitment among lecturers in higher education: comparison of six CEE countries. Organizacija 50:17–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/orga-2017-0004

Judge TA, Bono JE (2001) Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 86:80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.1.80

Kacmar KM, Bachrach DG, Harris KJ, Zivnuska S (2011) Fostering good citizenship through ethical leadership: exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. J Appl Psychol 96:633–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021872

Kacmar KM, Andrews MC, Harris KJ, Tepper BJ (2013) Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: the mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. J Bus Ethics 115:33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1373-8

Kanungo RN (2001) Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders. Can J Adm Sci/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration 18:257–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2001.tb00261.x

Kanungo RN, Mendonca M (1996) Ethical dimensions of leadership, vol 3. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Khuntia R, Suar D (2004) A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. J Bus Ethics 49:13–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:busi.0000013853.80287.da

Ko C, Ma J, Bartnik R, Haney MH, Kang M (2018) Ethical leadership: an integrative review and future research agenda. Ethics Behav 28:104–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2017.1318069

Koberg CS, Boss RW, Senjem JC, Goodman EA (1999) Antecedents and outcomes of empowerment: empirical evidence from the health care industry. Group Organ Manage 24:71–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601199241005

Koh HC, El’Fred H (2001) The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: a study of managers in Singapore. J Bus Ethics 29:309–324. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010741519818

Kouzes JM, Posner BZ (1992) Ethical leaders: an essay about being in love. J Bus Ethics 11:479–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00870559

Lam LW, Loi R, Chan KW, Liu Y (2016) Voice more and stay longer: how ethical leaders influence employee voice and exit intentions. Bus Ethics Q 26:277–300. https://doi.org/10.1017/beq.2016.30

Liden RC, Wayne SJ, Sparrowe RT (2000) An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. J Appl Psychol 85:407–416. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.85.3.407

Lin C-P, Lin C-P, Liu M-L, Liu M-L (2017) Examining the effects of corporate social responsibility and ethical leadership on turnover intention. Pers Rev 46:526–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-11-2015-0293

Liu C-M, Lin C-P (2018) Assessing the effects of responsible leadership and ethical conflict on behavioral intention. RMS 12:1003–1024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0236-1

Liu F, Chow IH-S, Zhang J-C, Huang M (2017) Organizational innovation climate and individual innovative behavior: exploring the moderating effects of psychological ownership and psychological empowerment. RMS. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0263-y

Martinko MJ, Gardner WL (1982) Learned helplessness: an alternative explanation for performance deficits. Acad Manage Rev 7:195–204. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1982.4285559

Mayer DM, Aquino K, Greenbaum RL, Kuenzi M (2012) Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Acad Manage J 55:151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276

Mccann JA, Langford PH, Rawlings RM (2006) Testing Behling and McFillen’s syncretical model of charismatic transformational leadership. Group Organ Manage 31:237–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273061

Menon S (2001) Employee empowerment: an integrative psychological approach. Appl Psychol 50:153–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00052

Mento AJ, Cartledge ND, Locke EA (1980) Maryland vs Michigan vs Minnesota: another look at the relationship of expectancy and goal difficulty to task performance. Organ Behav Hum Perform 25:419–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(80)90038-0

Meyer JP, Allen NJ (1991) A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum Resource Manage Rev 1:61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-z

Meyer JP, Allen NJ, Smith CA (1993) Commitment to organizations and occupations: extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. J Appl Psychol 78:538. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.78.4.538

Meyer JP, Stanley DJ, Herscovitch L, Topolnytsky L (2002) Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: a meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J Vocat Behav 61:20–52. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1842

Miao Q, Newman A, Yu J, Xu L (2013) The relationship between ethical leadership and unethical pro-organizational behavior: linear or curvilinear effects? J Bus Ethics 116:641–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1504-2

Mowday RT, Porter LW, Steers RM (1982) Employee-organization linkage: the psychology of commitment absenteism, and turn over. Academic Press Inc, London. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-509370-5.50010-1

Mulaik SA (2001) The curve-fitting problem: an objectivist view. Philos Sci 68:218–241. https://doi.org/10.1086/392874

Namasivayam K, Guchait P, Lei P (2014) The influence of leader empowering behaviors and employee psychological empowerment on customer satisfaction. Int J Contemp Hosp Manage 26:69–84. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2012-0218

Neubert MJ, Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Roberts JA, Chonko LB (2009) The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: evidence from the field. J Bus Ethics 90:157–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0037-9

Newman A, Sheikh AZ (2012) Organizational commitment in Chinese small-and medium-sized enterprises: the role of extrinsic, intrinsic and social rewards. Int J Hum Resource Manage 23:349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.561229

Newman A, Kiazad K, Miao Q, Cooper B (2014) Examining the cognitive and affective trust-based mechanisms underlying the relationship between ethical leadership and organisational citizenship: a case of the head leading the heart? J Bus Ethics 123:113–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1803-2

Newman A, Allen B, Miao Q (2015) I can see clearly now: the moderating effects of role clarity on subordinate responses to ethical leadership. Pers Rev 44:611–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-11-2013-0200

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (2010) Psychometric theory. Tata McGraw-Hill Ed., New Delhi

Ofori G (2009) Ethical leadership: examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. J Bus Ethics 90:533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0059-3

Okan T, Akyüz AM (2015) Exploring the relationship between ethical leadership and job satisfaction with the mediating role of the level of loyalty to supervisor. Bus Econ Res J 6:155–177. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v8n2p62

OPM USOoPM (2018) Federal Employee Viewpoint Survey. https://www.opm.gov/fevs/reports/governmentwide-reports/governmentwide-management-report/governmentwide-report/2018/2018-governmentwide-management-report.pdf. Accessed 16 March 2018

Petrick JA, Quinn JF (2001) The challenge of leadership accountability for integrity capacity as a strategic asset. J Bus Ethics 34:331–343. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1012597201948

Piccolo RF, Greenbaum R, Hartog DN, Folger R (2010) The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. J Organ Behav 31:259–278. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.627

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88:879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP (2012) Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu Rev Psychol 63:539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40:879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Puni A, Mohammed I, Asamoah E (2018) Transformational leadership and job satisfaction: the moderating effect of contingent reward. Leadersh Organ Dev J 39:522–537. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2017-0358

Renko M, El Tarabishy A, Carsrud AL, Brännback M (2015) Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J Small Bus Manage 53:54–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12086

Rhodes SR, Steers RM (1981) Conventional vs. worker-owned organizations. Hum Relat 34:1013–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678103401201

Ribeiro N, Gomes D, Kurian S (2018) Authentic leadership and performance: the mediating role of employees’ affective commitment. Soc Responsib J 14:213–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-06-2017-0111

Seibert SE, Silver SR, Randolph WA (2004) Taking empowerment to the next level: a multiple-level model of empowerment, performance, and satisfaction. Acad Manage J 47:332–349. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159585

Seyal AH, Rahman MNA, Rahim MM (2002) Determinants of academic use of the Internet: a structural equation model. Behav Inf Technol 21:71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290210123354

Shaffer JA, DeGeest D, Li A (2016) Tackling the problem of construct proliferation: a guide to assessing the discriminant validity of conceptually related constructs. Organ Res Methods 19:80–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115598239

Shamir B, Zakay E, Breinin E, Popper M (1998) Correlates of charismatic leader behavior in military units: subordinates’ attitudes, unit characteristics, and superiors’ appraisals of leader performance. Acad Manage J 41:387–409. https://doi.org/10.2307/257080

Sigler TH (1997) The empowerment experience: a study of front line employees. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Sigler TH, Pearson CM (2000) Creating an empowering culture: examining the relationship between organizational culture and perceptions of empowerment. J Qual Manage 5:27–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1084-8568(00)00011-0

Spreitzer GM (1995a) An empirical test of a comprehensive model of intrapersonal empowerment in the workplace. Am J Community Psychol 23:601–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02506984

Spreitzer GM (1995b) Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manage J 38:1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865

Spreitzer GM, Kizilos MA, Nason SW (1997) A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness, satisfaction, and strain. J Manage 23:679–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300504

Stouten J et al (2012) Special issue: leading with integrity: current perspectives on the psychology of ethical leadership. J Pers Psychol 11:204–208. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000033

Thomas KW, Tymon WG (1994) Does empowerment always work: understanding the role of intrinsic motivation and personal interpretation. J Manage Syst 6:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470773383.ch16

Thomas KW, Velthouse BA (1990) Cognitive elements of empowerment: an “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Acad Manage Rev 15:666–681. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1990.4310926

Thorlakson AJ, Murray RP (1996) An empirical study of empowerment in the workplace. Group Organ Manage 21:67–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601196211004

Treviño LK, Brown M, Hartman LP (2003) A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Hum Relat 56:5–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056001448

Treviño LK, Weaver GR, Reynolds SJ (2006) Behavioral ethics in organizations: a review. J Manage 32:951–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306294258

Vitell SJ, Davis DL (1990) The relationship between ethics and job satisfaction: an empirical investigation. J Bus Ethics 9:489–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00382842

Walumbwa FO, Schaubroeck J (2009) Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J Appl Psychol 94:1275–1286. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015848

Walumbwa FO, Mayer DM, Wang P, Wang H, Workman K, Christensen AL (2011) Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: the roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 115:204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.11.002

Wang H, Law KS, Hackett RD, Wang D, Chen ZX (2005) Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad Manage J 48:420–432. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.17407908

Wang H, Lu G, Liu Y (2017) Ethical leadership and loyalty to supervisor in china: the roles of interactional justice and collectivistic orientation. J Bus Ethics 146:529–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2916-6

Yukl G (2013) Leadership in organizations, 8th edn. Pearson, London

Yukl G, Van Fleet DD (1992) Theory and research on leadership in organizations. In: Dunnette MD, Hough LM (eds) Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, vol 3, 2nd edn. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, CA, pp 147–197

Zhu W (2008) The effect of ethical leadership on follower moral identity: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Leadersh Rev 8:62–73

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Qing, M., Asif, M., Hussain, A. et al. Exploring the impact of ethical leadership on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in public sector organizations: the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Rev Manag Sci 14, 1405–1432 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00340-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-019-00340-9

Keywords

- Ethical leadership

- Employees’ job satisfaction

- Affective commitment

- Psychological empowerment

- Structural equation modeling (SEM)