Abstract

Data on anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) are limited in children. This study is to determine the clinical features and outcomes of childhood-onset AAV. A retrospective study was performed on patients who were diagnosed with AAV before 18 years old in Xiangya Hospital. Their medical records were analyzed by retrospective review. Sixteen patients were diagnosed with AAV before 18 years old in the past 9 years, with an average age of 13.3 ± 3.3 years and 13 of them were female. There were 15 patients with microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and 1 with Wegener’s granulomatosis. The interval between onset of disease and diagnosis of AAV was 2 (1.5–3) months. Most patients (15/16, 93.8%) had multi-organ involvement, and all patients had renal involvement with 7 (43.8%) patients requiring dialysis at presentation. Eleven patients underwent a renal biopsy, of which mixed class and sclerotic class were the most two common histological types. All patients received immunosuppressive therapy for induction therapy including intravenous administrations of methylprednisolone (MP) pulse therapy for 8 patients. 8 patients (50%) achieved remission after induction therapy. After a median follow-up of 46.3 ± 36.1 months, nine (56.3%) patients progressed to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and 5 (31.3%) patients died. Childhood-onset AAV showed similar clinical and pathological features compared to those of adults, except that it usually occurs in girls. The most commonly involved organ was the kidney, and it had a high risk of progression to ESRD. Early diagnosis and initiation of appropriate immunomodulatory therapy would be important to improve outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a group of disorders characterized by necrotizing inflammation of small- to medium-sized vessels and includes microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). AAV involves multiple organs, particularly the lungs and kidneys, which might lead to rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and even progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) or death [1]. AAV mainly occurs in adults with the peak age of onset between fifty and seventy years old but can present at any age [2]. Compared with adults, the incidence of AAV in children is lower, and there are few studies on childhood-onset AAV [3, 4]. Most of the clinical information and treatment strategies applied to pediatric patients are inferred from adult evidence [5]. Therefore, it is necessary to give more attention and perform further studies on this population.

This retrospective study aimed to summarize the clinical features and outcomes of AAV in children in a single Chinese cohort, in order to provide some suggestions for childhood-onset AAV.

Materials and methods

Patients

All patients newly diagnosed with AAV between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2020, were recruited from the Departments of Pediatrics, Nephrology, Rheumatology and Immunology, Xiangya Hospital, a mixed tertiary hospital. Patients aged less than 18 years old and who fulfilled the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature for AAV were included [6]. Their clinical and pathological data were retrospectively collected from the medical records and analyzed. Moreover, we contacted each patient’s family via phone to determine their status by June 30, 2021.

Definitions

Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) was used to measure disease activity [7]. The Pediatric Vasculitis Activity Score (PVAS) was used instead of BVAS [8]. Organ system involvement was considered only if the manifestations were due to AAV [7]. Hematuria was defined as ≥ 5 red blood cells per high-power field in centrifuged urinary sediments. Complete remission was defined as the absence of disease activity attributable to active disease qualified by the need for ongoing stable maintenance immunosuppressive therapy for more than 1 month [9]. Partial remission was defined as at least 50% reduction of disease activity score and absence of new manifestations [9]. Treatment resistance was defined as unchanged or increased disease activity in patients with acute AAV after 4 weeks of treatment with standard induction therapy or a reduction of 50% in PVAS after 6 weeks of treatment. Chronic persistent disease defined as the presence of at least 1 major or 3 minor items on the PVSA list after 12 weeks of therapy [9]. It did not apply to any of the treatment response definitions if the patient died within 1 month.

Detection of ANCA

Cytoplasmic ANCA (c-ANCA) and perinuclear ANCA (p-ANCA) were detected by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) (Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany). ANCA against proteinase 3 (PR3-ANCA) and myeloperoxidase (MPO-ANCA) were tested using antigen-specific ELISA (Inova Diagnostics, San Diego, USA). Standard protocols were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Renal pathology

Direct immunofluorescence, light microscopy, and electron microscopy were all performed on each renal specimen. Then two renal pathologists examined specimens independently. Glomerular and tubulointerstitial lesions were evaluated according to the classification system of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis proposed by Berden et al. [10] and Chen et al. [11], respectively. In brief, all biopsies were classified as focal class (≥ 50% normal glomeruli), crescentic class (≥ 50% glomeruli with cellular crescents), sclerotic class (≥ 50% globally sclerotic glomeruli), and mixed class (the left). The percentage of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy was used for scored interstitial and tubular lesions semi-quantitatively that was score 0 for absent, 1 for 1–20%, 2 for 21–50%, and 3 for > 50%.

Ethics statement

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xiangya Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients’ parents or guardians included in the study.

Statistical analysis

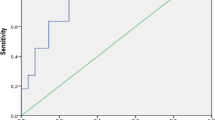

All data were analyzed using the statistical software Graphpad Prism, version 7. Normally distributed characteristics are presented as means and standard deviations (SDs). Non-normal distribution was expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR). Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to analyze patient overall survival and renal survival.

Results

Cohort characteristics and clinical features

A total of 16 patients ≤ 18 years were diagnosed with AAV in our center in the past 9 years. The average age of the patients was 13.3 ± 3.3 (5–18) years. A summary of all the childhood-onset AAV patients is shown in Table 1. Among the 16 patients, 13 were female (81.3%) and 3 were male (18.7%). There were 15 patients with MPA and 1 patient with GPA. The interval between onset of disease and the diagnosis of AAV was 2 (interquartile range (IQR), 1.5–3) months.

As shown in Table 2, kidney was the most frequently involved organ (16/16, 100%), and the most common manifestation was hematuria (100%). Fourteen (87.5%) patients presented with proteinuria. Eleven (68.8%) patients exhibited a rise in creatinine or fall in creatinine clearance and 7 (43.8%) of them required dialysis at presentation. The respiratory system was the second most involved organ with 11 (68.8%) patients exhibiting pulmonary involvement and followed by general condition (62.5%). Most patients (15/16, 93.8%) had multi-organ involvement. The PVAS was 18.7 ± 6.2.

Laboratory data

Laboratory data are listed in Table 3. Anemia was found in thirteen (81.3%) patients, and the mean hemoglobin was 91.3 ± 22.6 g/L. Only 4 and 2 patients had elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), respectively. Anti-MPO/p-ANCA positivity was seen in 14 (87.5%) and anti-PR3/c-ANCA positivity in 2 (12.5%) patients.

Renal Histopathology

Renal biopsies were performed in 11 patients (68.8%). The detailed histopathological characteristics are presented in Table 1. Among these 11 patients, there were 4 cases of sclerotic class, 1 case of focal class, 1 case of crescentic, and 5 cases of mixed class according to Berden et al. classification system of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. Tubulointerstitial injury scores of the cases ranged from 1 to 3 were 5, 3, and 3, respectively, according to Chen et al.

Treatment

All patients received corticosteroids for induction therapy (Table 1). Pulse methylprednisolone (MP) pulse therapy was performed in 8 patients. Nine patients received a combination of corticosteroid and intravenous cyclophosphamide. Other immunosuppressants for induction therapies included mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for 4 cases and tacrolimus for 2 cases. Three patients received plasma exchange (PE), and three patients received intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG).

Outcome

All patients were followed up until death or the final follow-up date (June 30, 2021). The time from diagnosis of AAV to the last follow-up was 46.3 ± 36.1 months (range 0.5–111 months). Eight (50%) patients achieved remission after induction therapy. At the end of follow-up, five patients maintained their clinical remission, nine patients were dialysis-dependent including 7 patients who required dialysis at the time of onset and 2 patients including one GPA relapsed and progressed to ESRD during the follow-up. None of the 7 patients receiving dialysis at presentation recovered their renal function. Among the 9 patients requiring dialysis, 4 cases died, 2 cases underwent renal transplantation, and 3 cases continued to receive dialysis until the last follow-up. The renal survival of the patients is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1a.

Of the 16 patients, 5 (31.3%) patients died and 4 of them, who received pulse MP, died during induction therapy. The causes of death were infection for 4 cases and cardiac arrest for 1 case. The patient survival of the patients is shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1b.

Discussion

Up to now, reports of childhood-onset AAV are rare, and the management mainly depends on clinical trials conducted in adults [5, 12]. In this retrospective study, we described the clinical characteristics and prognosis of AAV in children.

In our study, the male-to-female ratio was 1:4.3. In line with the other studies in childhood-onset AAV [13,14,15], girls seem more likely to be stricken with this disease. Although previous studies suggested that men and women were equally affected by AAV [16, 17]. The reason for this gender difference between children and adults is unclear. In addition, we found that pediatric AAV patients had similar clinical features compared with adults. In accordance with the composition of AAV in Chinese adults [16, 17], and unlike the United Kingdom and northern Europe [18], MPA was strikingly predominant in children in our study. It could be explained by genetic background differences [19].

Most patients had multi-organ involvement, and the most frequently involved organ was the kidney, present in all cases, including nearly half of patients requiring dialysis at presentation. Furthermore, 56.3% of patients were dialysis-dependent during follow-up, which was similar to the results of Wu et al. [20]. Yu et al. [15] and Sun et al. [21] also reported that the rate of renal insufficiency at diagnosis was high and dialysis dependence appeared to be more common in pediatric patients than in adults. However, none of these patients requiring dialysis at presentation stopped dialysis after therapy in our study. The renal survival appeared to be worse in pediatric patients than in adults, as more than 20% of MPO-AAV adult patients who were dialysis-dependent had achieved renal recovery by 12 months in our previous study [22]. On the other hand, the eGFR at presentation was also lower in those pediatric patients [23]. Previous studies demonstrated that patients with decreased eGFR had poor renal survival [24, 25], and lower baseline eGFR is an independent risk factor for ESRD progression in AAV children [20]. In addition, the PVAS in children was higher compared to adults. It was suggested that patients with a higher BVAS have less chance of recovering renal function. Another explanation might be due to the delay of diagnosis. In all, renal involvement in children showed severe manifestations at onset and the prognosis was poor, which suggested that we need to pay more attention to annual physical checks include urine screening [13].

Of the 11 patients who received renal biopsies, mixed class (45.5%) was the most common type, followed by sclerotic class (36.4%). The renal histopathology types were similar to those of adults [16]. Chang et al. reported that the probability of progressing to ESRD increased in mixed, crescentic, and sclerotic classes [26]. The focal class might have the best renal outcome. The poorer renal biopsy classes might also be attributable to worse renal outcome.

In our study, the majority of patients treated with steroids combined CYC for induction therapy. All patients received corticosteroids and half of them performed pulse MP. As far as we know, there are no specific guidelines for therapeutic management in pediatric AAV patients. The recommended regimens were inferred from adult experiences and studies. It has been recommended that using pulse methylprednisolone (MP) before starting high dose oral steroids by Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines (2012) [27]. However, our previous work suggested that pulse MP to standard immunosuppressive induction therapy appeared to be of no benefit in terms of improving patient outcomes [22]. The benefits and risks of pulse MP need further research.

After a median follow-up of 46.3 months, 5 of the 16 (31.3%) patients died and 4 deaths were at the dialysis-dependent stage. Furthermore, 4 patients who received pulse MP died during induction therapy. The main cause of death was infection. The relatively high mortality rate might be explained by a high PVAS at presentation as BVAS was demonstrated to be an independent predictor for all-cause death [28]. What’s more, both BVAS and eGFR at onset were shown to be an independent predictor for therapy-related death [29].

There are also some limitations in our study. First, this was a retrospective study that we could not obtain precise information prior to case presentation. Second, this study was performed in a single center and the sample size was small, and as such our results may not be generalizable to other populations. Further observation of more patients in multiple centers is needed.

In conclusion, childhood-onset AAV is a complex disease that can lead to serious consequences or even death and any organ of the body can be involved. Early diagnosis and initiation of appropriate immunomodulatory therapy would be important to improve outcomes.

References

Ponte C, Agueda AF, Luqmani RA. Clinical features and structured clinical evaluation of vasculitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32(1):31–51.

Hamour SM, Salama AD. ANCA comes of age-but with caveats. Kidney Int. 2011;79(7):699–701.

Jariwala M, Laxer RM. Childhood GPA, EGPA, and MPA. Clin Immunol. 2020;211:108325.

Jariwala MP, Laxer RM. Primary vasculitis in childhood: GPA and MPA in childhood. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:226.

Lee JJY, Alsaleem A, Chiang GPK, et al. Hallmark trials in ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV) for the pediatric rheumatologist. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2019;17(1):31.

Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1–11.

Mukhtyar C, Lee R, Brown D, et al. Modification and validation of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (version 3). Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1827–32.

Dolezalova P, Price-Kuehne FE, Ozen S, et al. Disease activity assessment in childhood vasculitis: development and preliminary validation of the Paediatric Vasculitis Activity Score (PVAS). Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1628–33.

Hellmich B, Flossmann O, Gross WL, et al. EULAR recommendations for conducting clinical studies and/or clinical trials in systemic vasculitis: focus on anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(5):605–17.

Berden AE, Ferrario F, Hagen EC, et al. Histopathologic classification of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(10):1628–36.

Chen YX, Xu J, Pan XX, et al. Histopathological classification and renal outcome in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated renal vasculitis: a study of 186 patients and metaanalysis. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(3):304–13.

Calatroni M, Oliva E, Gianfreda D, et al. ANCA-associated vasculitis in childhood: recent advances. Ital J Pediatr. 2017;43(1):46.

Hirano D, Ishikawa T, Inaba A, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of childhood-onset anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a clinicopathological analysis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34(8):1425–33.

Iudici M, Puechal X, Pagnoux C, et al. Brief report: childhood-onset systemic necrotizing vasculitides: long-term data from the french vasculitis study group registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1959–65.

Yu F, Huang JP, Zou WZ, Zhao MH. The clinical features of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated systemic vasculitis in Chinese children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(4):497–502.

Meng T, Zhong Y, Chen J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis in Chinese elderly and very elderly patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021;53(9):1875–81.

Xin G, Zhao MH, Wang HY. Detection rate and antigenic specificities of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in Chinese patients with clinically suspected vasculitis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(3):559–62.

Jennette JC, Nachman PH. ANCA glomerulonephritis and vasculitis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(10):1680–91.

Wang HY, Cui Z, Pei ZY, et al. Risk HLA class II alleles and amino acid residues in myeloperoxidase-ANCA-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int. 2019;96(4):1010–9.

Wu J, Pei Y, Rong L, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of 34 cases of primary antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis in Chinese children. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:656307.

Sun L, Wang H, Jiang X, et al. Clinical and pathological features of microscopic polyangiitis in 20 children. J Rheumatol. 2014;41(8):1712–9.

Huang L, Zhong Y, Ooi JD, et al. The effect of pulse methylprednisolone induction therapy in Chinese patients with dialysis-dependent MPO-ANCA associated vasculitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;76:105883.

Wu T, Zhong Y, Zhou Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis in 269 patients with antineutrophil cytoplasimc antibody associated vasculitis. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;45(8):916–22.

Zoshima T, Suzuki K, Suzuki F, et al. ANCA-associated nephritis without crescent formation has atypical clinicopathological features: a multicenter retrospective study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2020;24(11):999–1006.

Calatroni M, Consonni F, Allinovi M, et al.( 2021) Prognostic factors and long-term outcome with ANCA-associated kidney vasculitis in childhood. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. Online ahead of print.

Chang DY, Wu LH, Liu G, Chen M, Kallenberg CG, Zhao MH. Re-evaluation of the histopathologic classification of ANCA-associated glomerulonephritis: a study of 121 patients in a single center. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(6):2343–9.

KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Glomerulonephritis (2012). Chapter 13: Pauci-immune focal and segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2012;2(2):233–9.

Bai YH, Li ZY, Chang DY, Chen M, Kallenberg CG, Zhao MH. The BVAS is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events and cardiovascular disease-related mortality in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis: a study of 504 cases in a single Chinese center. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47(4):524–9.

Flossmann O, Berden A, de Groot K, et al. Long-term patient survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):488–94.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81800641 to TM), the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2005000 to XX), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan province (2018WK2060 to XX and 2020WK2008 to YZ), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2020RC5002 to JO), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (2021JJ31130 to YZ, 2020JJ6109 to CS and 2019JJ40515 to WN), and Chinese Society of Nephrology (18020010780 to YZ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, T., Shen, C., Tang, R. et al. Clinical features and outcomes of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated vasculitis in Chinese childhood-onset patients. Clin Exp Med 22, 447–453 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-021-00762-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10238-021-00762-4