Abstract

Purpose

Coffee drinking has been linked to many positive health effects, including reduced risk of some cancers. The present study aimed to provide an overview of the collective evidence on the association between coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) through an umbrella review of the published systematic reviews.

Methods

This PRISMA-compliant systematic review of systematic reviews assessed the association between coffee drinking and the risk of CRC. An umbrella review approach was followed in a qualitative narrative manner. The quality of included reviews was assessed by the AMSTAR 2 checklist. The main outcome was the association between coffee drinking and CRC and colon and rectal cancer separately.

Results

Fourteen systematic reviews were included in this umbrella review. Coffee drinking was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of CRC according to five reviews (11–24%), colon cancer according to two reviews (9–21%), and rectal cancer according to one review (25%). One review reported a significant risk reduction of CRC by 7% with drinking six or more cups of coffee per day and another review reported a significant risk reduction of 8% with five cups per day reaching 12% with six cups per day. Decaffeinated coffee was associated with a significant risk reduction according to three reviews.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting caffeinated coffee as associated with a reduced risk of CRC is inconsistent. Dose-dependent relation analysis suggests that the protective effect of coffee drinking against CRC is evident with the consumption of five or more cups per day.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coffee is second only to water as the most consumed beverage worldwide [1]. It contains a complex mixture of chemical compounds such as caffeine, methylxanthines, and polyphenols, among others. These compounds have diverse effects on the human body and their health benefits have been rigorously investigated and supported by multiple experimental studies [2]. Some epidemiological investigations suggest an association between coffee consumption and reduced risk of several chronic diseases, including cardiovascular, hepatic, and gastrointestinal diseases, and diabetes. Interestingly and in contrast with the common beliefs, recent meta-analyses concluded that a lower risk of cardiovascular disease was associated with moderate coffee consumption (3–5 cups/day) [3] and that heavy coffee consumption (≥ 6 cups/day) was not associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular complications [4].

Oxidative stress and inflammation are commonly regarded as the basis of many pathological processes, such as carcinogenesis. As a result of the well-known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of caffeine and other chemical compounds found in coffee, the anticancer effects of coffee have been studied for decades [5, 6]. A recent umbrella review identified robust evidence for a dose-dependent inverse association between endometrial and liver cancers and coffee consumption [7]. In contradiction, other studies reported an increased risk of bladder cancer associated with higher coffee consumption [8, 9].

Multiple studies have investigated the association between coffee consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). The results of the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study indicated an inverse correlation between coffee consumption and CRC risk [10]. Another population-based study found that increased coffee consumption was associated with lower odds of developing CRC [11]. Nonetheless, a recent systematic review of prospective studies found a significant degree of heterogeneity in the correlation between coffee consumption and CRC [12]. A hospital-based case–control study identified an inverse association between the risk of CRC and coffee consumption in a Korean population, with a possible attenuating effect of coffee additives such as cream and sugar [13]. The present study aimed to provide an overview of the collective evidence on the association between coffee consumption and the risk of CRC through an umbrella review of the published systematic reviews on this subject.

Methods

Review registration and ethics approval

The protocol of the present review was registered in the prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42022333779). As a result of the nature of this study, ethics approval was deemed exempt on the basis of our institutional review board guidelines.

Search strategy

A qualitative umbrella review of systematic reviews assessing the association between coffee drinking and the risk of CRC was performed in adherence to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [14] and in line with the reporting guideline of the umbrella review approach [15]. PubMed and Scopus were searched from their inception through May 2022 by two independent authors (S.E., S.B.) for systematic reviews that reported the association between coffee drinking and CRC risk.

The following keywords were utilized in the search: “coffee” OR “caffeine” AND “colorectal cancer” OR “colorectal carcinoma” OR “colon cancer” OR “rectal cancer” AND “association” OR “relation” OR “link”. On searching PubMed, the “related articles” function was activated to search for other potentially relevant studies. The bibliography section of the articles retrieved was manually screened.

Selection criteria

We included systematic reviews with or without concurrent meta-analysis with an available English full text that fulfilled the following PICO criteria:

-

P (population): General population, including patients who developed CRC

-

I (intervention): Regular coffee drinking

-

C (comparator): No coffee drinking

-

O (outcome): Risk of colorectal cancer overall and colon and rectal cancer separately

We excluded non-systematic narrative reviews, scoping reviews, original articles, case reports, editorials, and experimental studies. We also excluded articles that did not entail sufficient information about the primary outcome of this review and articles whose full text we could not obtain.

Data collection

The following data were extracted from the selected studies into an Excel spreadsheet:

-

Authors, design, country of the review

-

Number and type of studies and type of cohorts included

-

Inclusion criteria

-

Risk reduction of CRC, colon cancer, and rectal cancer associated with coffee drinking, expressed as relative risk or odds ratio with 95% CI

-

Dose-dependent relation between coffee drinking and CRC risk

Quality assessment

Two authors (S.E., Z.G.) independently assessed the quality of the systematic reviews included in this umbrella review. The critical appraisal of the quality of the systematic reviews was performed using the AMSTAR 2 tool which consists of 16 questions and the overall confidence in the results of the review is rated as high, moderate, low, and critically low [16].

Results

Characteristics of the studies

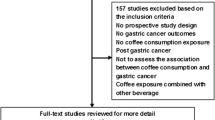

The initial literature search returned 533 articles; after exclusion of the studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 14 systematic reviews [12, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] were included in the present umbrella review (Fig. 1). The reviews were published between 1998 and 2020; the majority of the studies were based in Asian countries (n = 8), three were based in the USA, and another three in Europe. The number of studies included in the reviews ranged from 2 to 59 and the number of participants ranged from 4846 to 3,402,167. Four studies exclusively included Asian patients. Eight reviews included prospective cohort studies only, five included cohort and case–control studies and one by Galeone et al. [26] included case–control studies only. Ten reviews were of critically low quality and four of low quality (Table 1). The inclusion criteria of each review are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Relative risk of colon, rectal, and colorectal cancer

Five of 11 reviews that assessed the relative risk of CRC in coffee drinkers versus non-drinkers reported a significant risk reduction associated with coffee drinking. In the reviews by Akter et al. [22] and Li et al. [23], the subgroup analysis of case–control studies only revealed a significant risk reduction whereas the analysis of cohort studies only did not reveal the same. The significant risk reduction varied across the reviews from 11% to 24% with a median of 17%.

Two of 11 reviews that assessed the relative risk of colon cancer in coffee drinkers versus non-drinkers found a significant risk reduction associated with coffee drinking, ranging from 9% to 21%. Only one of nine reviews that assessed the relative risk of rectal cancer in coffee drinkers versus non-drinkers reported a significant risk reduction of 25% when case–control studies were separately analyzed (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Dose-dependent relation

Five reviews reported the risk reduction of CRC associated with drinking coffee in a dose-dependent manner. While a subgroup analysis of cohort studies only did not reveal a significant association in the review by Horisaki et al. [19], analysis of case–control studies alone revealed a significant risk reduction with all coffee doses, from one to six cups per day.

Gan et al. [21] reported a significant risk reduction of 7% with drinking six or more cups of coffee per day, whereas Tian et al. [24] reported a significant risk reduction of 8% with five cups per day and reaching 12% with six cups per day (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Subgroup analyses

Decaffeinated coffee was associated with a significant risk reduction ranging from 11% to 15%, according to three reviews (Micek et al. [18], Sartini et al. [12], Gan et al. [21]). Studies published before the year 2000 reported a significant risk reduction of 11%. Two studies (Sartini et al. [12] and Galeone et al. [26]) reported a significant risk reduction in the North American cohorts (17% and 24%) and two (Galeone et al. [26] and Giovannucci [29]) reported a significant reduction in Asian cohorts (39% and 35%) (Table 4).

Discussion

The present umbrella review summarized the findings of 14 systematic reviews in which the association between coffee drinking and the risk of CRC was assessed. While five reviews reported a significant reduction in CRC risk associated with regular coffee drinking, six reviews did not find a significant association. On the assessment of the risk of colon cancer separately, only two reviews reported a significant risk reduction of colon cancer with coffee drinking. In order to understand the implications of these results, some factors that may affect the association between coffee drinking and CRC should be emphasized.

The first factor that may impact this association is the study design. Four of the reviews that reported a significant association between coffee drinking and CRC risk included case–control studies only in the analysis. Meanwhile, the systematic reviews that included only prospective cohort studies did not report a significant association. This observation can be explained by the difference in the nature of both study designs. Cohort studies divide the cohort according to the exposure (coffee drinking) and then follow-up each group to detect the outcome (CRC). In contrast, a case–control study begins with the outcome of interest and then determines the proportion of individuals that developed the outcome according to the exposure. While the cohort design is more robust in assessing a causal relationship between the exposure and outcome, it is usually more challenging and requires long follow-up as the disease of interest may occur after a long time of exposure. Conversely, case–control studies are simpler, less costly, and do not require long-term follow-up, yet are more liable to bias and less reliable in showing a causal relationship compared to cohort studies [30, 31]. These factors may explain why reviews of case–control studies were able to find a significant reduction of CRC risk with coffee drinking whereas reviews of cohort studies failed to do so, probably because they would have needed much longer follow-up to detect the incidence of CRC in each group.

The second factor is the patient cohort studied. Four reviews included Asian patient cohorts only, and three of them did not report a significant risk reduction of CRC with coffee drinking. However, the two reviews by Galeone et al. [26] and Giovannucci [29], which included a global cohort of patients, found a significant association between coffee drinking and CRC risk on subgroup analysis of Asian patients only. Akter et al. [22] proposed that Asian people may have a different association between coffee consumption and CRC than Westerners since Asian people have different body fat distribution and insulin secretion capacity, and thus the impact of coffee drinking on glucose metabolism might be different [32, 33]. Nonetheless, the same authors concluded in their review that there is insufficient evidence to support the effect of coffee drinking on CRC risk in the Japanese population. Furthermore, Sartini et al. [12] and Galeone et al. [26] reported a significant reduction of CRC risk associated with regular coffee drinking in the North American cohorts whereas Je et al. [28] and Giovannucci et al. [29] did not find a similar significant association in the US cohorts. These disparate findings reflect an inconsistent effect of ethnicity and race on the association between coffee drinking and CRC and warrant further investigation to verify if the patients’ background has a true impact on this association.

The third factor that may affect the association between coffee drinking and CRC risk is the type of coffee. Three systematic reviews reported that the consumption of decaffeinated coffee is associated with a significant reduction of CRC risk, ranging between 11% and 15%. Sartini and colleagues [12] found that the type of coffee has an important impact as drinking decaffeinated coffee was significantly associated with a reduced risk of CRC, whereas caffeinated coffee had no significant impact. Gan et al. [21] tried to explain the inverse association between CRC risk and decaffeinated but not with caffeinated coffee consumption. They elaborated that this difference might be attributable to residual confounders related to different lifestyles between decaffeinated and caffeinated coffee consumers. A specific confounder is that decaffeinated coffee drinkers tend to consume less alcohol and red meat and eat more vegetables and fruits [10].

The frequency of coffee consumption is another factor that might impact its association with CRC risk. Two systematic reviews found that a significant reduction of CRC risk would be associated with drinking not less than five cups of coffee per day. Only one analysis of case–control studies by Horisaki et al. [19] found significant association between coffee drinking and CRC risk regardless of the number of cups consumed per day. Gan et al. [21] reported a non-linear association between coffee consumption and colorectal and colon cancer risk. This association might be attributed to a complex biological mechanism. Coffee contains a mixture of compounds, some of which, such as aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines, have mutagenic and potential carcinogenic properties whereas other compounds, such as phenolic acids, cafestol, and kahweol, have strong antioxidant and anticarcinogenic properties [34,35,36]. Thus, heavy consumption of more than five cups of coffee per day may render the beneficial effects greater than the negative ones and would strengthen the inverse association between higher coffee consumption and CRC.

Gan et al. [21] had an interesting observation that the inverse association between coffee consumption and CRC risk was significant in the studies published before the year 2000, but not afterwards. They tried to explain this observation by the change in the coffee brewing methods over time, with the filter method becoming more popular than the unfiltered one. In the earlier studies, boiled unfiltered coffee was more commonly consumed [36] and this type of coffee has a higher concentration of cafestol and kahweol, which may lower CRC risk by reducing bile acid synthesis and secretion and inhibiting the activity of CYP1A2 and NAT2 [37,38,39].

The present review has a number of limitations that include the small number and low quality of the systematic reviews included. No quantitative analysis of the effect estimates of the association between coffee drinking and CRC was made because of the heterogeneity of the studies and overlap of the primary studies included in the systematic reviews. The dose-dependent relation was analyzed on the basis of the number of cups of coffee; however, the size of the cup may vary among different countries and a more accurate analysis would use the amount of coffee consumed in milliliters. The lack of information on coffee brewing methods and preparation is another important limitation.

Conclusion

There is inconsistent evidence supporting that regular coffee drinking can reduce the risk of CRC. Decaffeinated coffee may provide more a protective effect than caffeinated coffee. Dose-dependent relation analysis suggests that the protective effect of coffee drinking against CRC is more evident with consumption of five or more cups per day.

References

Higdon JV, Frei B (2006) Coffee and health: a review of recent human research. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 46:101–123

Poole R, Kennedy OJ, Roderick P, Fallowfield JA, Hayes PC, Parkes J (2018) Coffee consumption and health: umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 360:k194 (Published correction appears in BMJ)

Ding M, Bhupathiraju SN, Satija A, van Dam RM, Hu FB (2014) Long-term coffee consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation 129:643–659

Malerba S, Turati F, Galeone C et al (2013) A meta-analysis of prospective studies of coffee consumption and mortality for all causes, cancers and cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 28:527–539

Park SY, Freedman ND, Haiman CA, Le Marchand L, Wilkens LR, Setiawan VW (2018) Prospective study of coffee consumption and cancer incidence in non-white populations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27:928–935

Weinstein ND (1985) Reactions to life-style warnings: coffee and cancer. Health Educ Q 12:129–134

Zhao LG, Li ZY, Feng GS et al (2020) Coffee drinking and cancer risk: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Cancer 20:101

Marrett LD, Walter SD, Meigs JW (1983) Coffee drinking and bladder cancer in Connecticut. Am J Epidemiol 117:113–127

Simon D, Yen S, Cole P (1975) Coffee drinking and cancer of the lower urinary tract. J Natl Cancer Inst 54:587–591

Sinha R, Cross AJ, Daniel CR et al (2012) Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee and tea intakes and risk of colorectal cancer in a large prospective study. Am J Clin Nutr 96:374–381

Schmit SL, Rennert HS, Rennert G, Gruber SB (2016) Coffee consumption and the risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:634–639

Sartini M, Bragazzi NL, Spagnolo AM et al (2019) Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutrients 11:694

Kim Y, Lee J, Oh JH et al (2021) The association between coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in a Korean population. Nutrients 13:2753

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097

Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P (2015) Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc 13:132–140

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G et al (2017) AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 358:j4008

Bae JM (2020) Coffee consumption and colon cancer risk: a meta-epidemiological study of Asian cohort studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 21:1177–1179

Micek A, Gniadek A, Kawalec P, Brzostek T (2019) Coffee consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a dose-response meta-analysis on prospective cohort studies. Int J Food Sci Nutr 70:986–1006

Horisaki K, Takahashi K, Ito H, Matsui S (2018) A dose-response meta-analysis of coffee consumption and colorectal cancer risk in the Japanese population: application of a cubic-spline model. J Epidemiol 28:503–509

Kashino I, Akter S, Mizoue T et al (2018) Coffee drinking and colorectal cancer and its subsites: a pooled analysis of 8 cohort studies in Japan. Int J Cancer 143:307–316

Gan Y, Wu J, Zhang S et al (2017) Association of coffee consumption with risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Oncotarget 8:18699–18711

Akter S, Kashino I, Mizoue T et al (2016) Coffee drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review and meta-analysis among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol 46:781–787

Li G, Ma D, Zhang Y, Zheng W, Wang P (2013) Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr 16:346–537

Tian C, Wang W, Hong Z, Zhang X (2013) Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a dose-response analysis of observational studies. Cancer Causes Control 24:1265–1268

Yu X, Bao Z, Zou J, Dong J (2011) Coffee consumption and risk of cancers: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMC Cancer 11:96

Galeone C, Turati F, La Vecchia C, Tavani A (2010) Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Cancer Causes Control 21:1949–1959

Zhang X, Albanes D, Beeson WL et al (2010) Risk of colon cancer and coffee, tea, and sugar-sweetened soft drink intake: pooled analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:771–783

Je Y, Liu W, Giovannucci E (2009) Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer 124:1662–1668

Giovannucci E (1998) Meta-analysis of coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Am J Epidemiol 147:1043–1052

Grace-Martin K (2022) Cohort and case-control studies: pro’s and con’s. https://www.theanalysisfactor.com/cohort-and-case-control-studies-pros-and-cons/. Accessed May 22, 2022.

Song JW, Chung KC (2010) Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plast Reconstr Surg 126:2234–2242

Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ et al (2011) National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377:557–567

Moller JB, Pedersen M, Tanaka H et al (2014) Body composition is the main determinant for the difference in type 2 diabetes pathophysiology between Japanese and Caucasians. Diabetes Care 37:796–804

Ivankovic S, Seibel J, Komitowski D, Spiegelhalder B, Preussmann R, Siddiqi M (1998) Caffeine-derived N-nitroso compounds. V. Carcinogenicity of mononitrosocaffeidine and dinitrosocaffeidine in bd-ix rats. Carcinogenesis 19:933–937

Ferruzzi MG (2010) The influence of beverage composition on delivery of phenolic compounds from coffee and tea. Physiol Behav 100:33–41

Cavin C, Holzhaeuser D, Scharf G, Constable A, Huber WW, Schilter B (2002) Cafestol and kahweol, two coffee specific diterpenes with anticarcinogenic activity. Food Chem Toxicol 40:1155–1163

Gross G, Jaccaud E, Huggett AC (1997) Analysis of the content of the diterpenes cafestol and kahweol in coffee brews. Food Chem Toxicol 35:547–554

Post SM, de Wit EC, Princen HM (1997) Cafestol, the cholesterol-raising factor in boiled coffee, suppresses bile acid synthesis by downregulation of cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase and sterol 27-hydroxylase in rat hepatocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17:3064–3070

Ricketts ML, Boekschoten MV, Kreeft AJ et al (2007) The cholesterol-raising factor from coffee beans, cafestol, as an agonist ligand for the farnesoid and pregnane X receptors. Mol Endocrinol 21:1603–1616

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wexner reports receiving consulting fees from ARC/Corvus, Astellas, Baxter, Becton Dickinson, GI Supply, ICON Language Services, Intuitive Surgical, Leading BioSciences, Livsmed, Medtronic, Olympus Surgical, Stryker, Takeda and receiving royalties from Intuitive Surgical and Karl Storz Endoscopy America Inc. Dr. Emile reports receiving consulting fees from SafeHeal.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Emile, S.H., Barsom, S.H., Garoufalia, Z. et al. Does drinking coffee reduce the risk of colorectal cancer? A qualitative umbrella review of systematic reviews. Tech Coloproctol 27, 961–968 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-023-02804-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-023-02804-3