Abstract

Scrotal pain is a common acute presentation for medical care. Testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis are two diagnoses for which early detection is critical and their sonographic imaging features have been thoroughly described in the radiologic literature. Other important conditions for which radiologists must be aware have received less attention. This article will highlight key traumatic and non-traumatic causes of acute scrotal pain other than testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis that may present in the emergency department setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Scrotal pain is a common presentation in the emergency and urgent care setting [1, 2]. Typical penoscrotal emergencies include traumatic, ischemic, and infectious/inflammatory etiologies. Following physical exam, sonography allows for a cost-effective, non-ionizing assessment of the scrotal contents (and of the penis and inguinal regions in select cases) [3]. Accurate and timely identification of the cause of pain at the point of care ensures the appropriate allocation of treatment and follow-up.

Testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis are two of the most common diagnoses for which early detection is critical and have been described in detail previously in the literature [1, 2, 4,5,6,7,8]. Other important conditions for which radiologists must be aware have received less attention [2]. This article will highlight key traumatic and non-traumatic causes of acute scrotal pain other than testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis that may present in the emergency department setting.

Scrotal ultrasound technique

The patient is typically positioned supine for the scrotal sonographic examination, using a rolled towel or sheet between the legs to elevate and support the scrotum. The penis may be positioned superiorly or superolaterally by the patient and draped for privacy. Linear high-frequency transducers (7.5–15 MHz) are used to examine both testicles in sagittal and transverse planes, with particular attention to gray-scale and Doppler symmetry. There may be a need to use a lower-frequency curvilinear transducer if there is significant scrotal edema. Examining the asymptomatic side first helps ascertain a baseline and allows the patient to become accustomed to the exam. Power Doppler increases sensitivity for flow detection and can be useful in physiologic low flow states, including pediatrics. However, “flash” artifacts from motion can mimic flow in this setting, and therefore careful assessment is advised [1, 2]. Side-to-side comparison of the skin, epididymal structures, and testes is useful, especially with regard to echotexture and color Doppler flow patterns. For the testicles, this is best accomplished with the “saddle view,” which includes both testicles in the field of view and precludes the potential for technical differences contributing to asymmetry.

Sonographic features of testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis have been described previously at length in the literature and are not included in this review. However, when there is no evidence of testicular torsion or epididymo-orchitis, we recommend scrutinizing the scrotum for the following broad categories of alternate diagnoses, organized by anatomic region of interest:

Testicle/epididymis

Torsed appendages

Torsion of a testicular or epididymal appendage is a common cause of acute scrotal pain in prepubertal males, more commonly occurring on the left [9, 10]. Patients typically present with unilateral focal scrotal pain and may have a classic “blue dot sign” upon physical exam. Sonographic exam demonstrates a small ovoid extratesticular or extraepididymal mass of variable echogenicity and without internal blood flow (Fig. 1). There may also be ipsilateral scrotal skin thickening and/or reactive hydrocele [11, 12]. An echogenic shadowing avascular focus between the testicle and epididymis represents a remotely torsed appendage (also known as a scrotolith or scrotal pearl).

Differentiating a torsed testicular appendage from a torsed epididymal appendage is not always possible but of no clinical significance as management of either entity is conservative.

Abscess: intratesticle or epididymis

Epididymitis or orchitis may be complicated by abscess formation if left undiagnosed or untreated. Bacterial infections of the male lower urinary tract most often spread in an anatomically retrograde manner. Therefore, the first site of infected nidus is often the epididymal tail and head. Sonographic findings include round or ovoid intratesticular or intra-epididymal collections of variable complexity and peripheral vascularity (Fig. 2). Surgical drainage may be required if the abscess fails to resolve after a trial of conservative antibiotic therapy [1, 13]. Prolonged presence of untreated abscess or large size may also predispose to pressure necrosis of the testicular parenchyma.

Trauma

Hematoma

Emergent US has high sensitivity for detecting testicular injury [14, 15]. Hematomas are of variable gray-scale complexity and size, but are uniform without internal or peripheral flow on Doppler interrogation. Intratesticular hematoma may be difficult to differentiate from parenchymal contusion if there is no defined collection (Fig. 3). A large size may necessitate surgical exploration. When managed conservatively, intratesticular hematomas warrant sonographic follow-up to resolution due to the high risk for subsequent infection and necrosis, which could require orchiectomy [14, 16].

Further, documenting resolution on follow-up allows for the exclusion of incidental tumor, which can mimic or be masked by posttraumatic change [14, 16].

Testicle fracture or rupture

Intrascrotal injury most often results from blunt trauma, predisposing to testicular fracture or rupture. Testicular fracture appears as a band-like or linear hypoechoic abnormality extending across the parenchyma. This reflects a “break” in normal architecture although with INTACT tunica albuginea and smooth contour. A fracture should not be confused with the normal echogenic band-like mediastinum testis. Testicular rupture is defined by visible discontinuity or irregularity of the normally echogenic and smooth tunica albuginea [17] (Fig. 4). Extrusion of testicular parenchyma through a focal tunical defect may be present or associated with hemorrhage. Evident or even suspected rupture requires emergent surgical exploration as delayed management is associated with an increased risk of infection and necrosis, which can lead to infertility and/or hormonal dysfunction [4, 18, 19].

Penetrating testicular trauma

The most common source of penetrating testicular injury is gunshot wounds [20]. US enables detection of ballistic fragments, surveys testicular parenchymal injury, and screens for vascular compromise. Assessing for spermatic cord transection is also a key requirement. Although ballistic fragments may not be retained in the scrotal soft tissues, identification of their hypoechoic tracks signifies violation of the deep scrotal structures and may indicate need for surgical exploration [21].

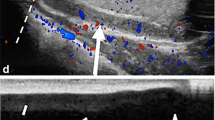

Intratesticular varicocele

Intratesticular varicoceles may cause unilateral vague discomfort or be palpated as an intratesticular mass. At US, the appearance will be hypo- or anechoic tubular structures within the substance of the testicle in close proximity to the mediastinum testis and may be traced in continuity with the pampiniform plexus. Upon application of color Doppler, these structures will demonstrate color flow and venous spectral waveforms with Valsalva maneuvers [2, 22] (Fig. 5). There is not always an associated extratesticular varicocele [23].

Scrotal collections

Extratesticular collections may accumulate between the parietal and visceral layers of a patent processus vaginalis and are the most common cause of painless scrotal swelling.

Simple hydrocele

Simple hydroceles may be idiopathic or reactive to epididymo-orchitis, trauma, torsion, or neoplasm [24]. At US, simple hydrocele collections are uniformly anechoic and avascular.

Complex hydrocele

Complex hydroceles include hematoceles and pyocele, depending on the primary etiology. These extratesticular collections contain internal echoes of variable echogenicity and mobility. Acute hematoceles will contain homogeneously echogenic material. With age, the blood will become progressively more organized with hypoechoic internal components or fluid-fluid levels [2, 17] (Fig. 6). Infected hydroceles (pyoceles) may organize and/or develop peripheral vascular flow, forming an extratesticular abscess. Gas bubbles within the pyocele appear as foci of dirty shadowing [24]. Large complex hydroceles may exert substantial mass effect and can cause abnormal testicular lie, giving a “pseudo-torsed” gray-scale appearance. Evaluation for vascular compromise, including secondary segmental testicular infarction, should always be performed in this setting [25].

Complex hydrocele/hematocele. a Homogeneously hyperechoic fluid collects external to the right testicle (arrows) in this patient status post trauma, in keeping with an acute hematocele. b CT image from the same patient showing blood in the right hemiscrotum (arrow). c Follow-up ultrasound 2 months later showing the now chronic fluid has decreased in echogenicity and developed thin internal septations (arrows)

Inguinal hernia

Inguinal hernias are detectable with scrotal sonography, particularly if there is descent of intraabdominal fat or bowel into the scrotal sac. This may be best appreciated by Valsalva maneuver or by scanning with the patient standing. In rare instances, herniated urinary bladder or the appendix (aka Amyand’s hernia) may be visualized in the hernia sac [26]. Patients may present with acute pain when there is incarceration of the inguinal contents.

Spermatic cord

Funiculitis

Funiculitis (or corditis) is inflammation of the spermatic cord and may be due to vasitis or direct spread of infection/inflammation from the vas deferens. Funiculitis often presents as painful unilateral scrotal pain with edematous enlargement of the ipsilateral spermatic cord, heterogeneous echo texture, and hyperemia with color Doppler [27] (Fig. 7). The engorged para-funicular vessels are not to be confused with an extratesticular varicose, which should show increased caliber and flow with Valsalva maneuver [28, 29]. Comparison to the contralateral spermatic cord may prove beneficial, though be aware this process can be bilateral.

Funicular collections

Although rare, hydroceles associated with the high intrascrotal spermatic cord may occur from irregular closure of the processus vaginalis, resulting in discrete potential spaces that do not freely communicate with the peritoneum. Resultant beaded or loculated fluid collections may accumulate alongside the spermatic cord, external to the testis or epididymis. These are called encysted hydroceles if there is a focal fluid collection that does not communicate with the scrotum or the peritoneum [24, 30] (Fig. 8).

Varicocele

Varicoceles represent extratesticular compressible tangles of pampiniform veins, whose individual caliber measures more than 2 mm. Standing position and Valsalva maneuver may incite further distention of the veins. Varicoceles are most common on the left side [25].

Penis

Penile trauma/fracture

Penile fracture is most likely to occur from blunt trauma when the penis is erect (intracoital mechanism) because of the physiologic stretching and thinning of the cavernosal tunica albuginea [31, 32]. When history suggests penile fracture, assessing the integrity of the penile tunica albuginea is critical. Assess the penis in anatomic position (penis laying on the abdomen) with high-frequency linear transducer using ample coupling gel (“standoff pad”). On physical exam, the penis will be bruised and may be swollen with a purplish hue (“eggplant penis”). Sonographically, survey the length of the tunica for discontinuity of its normally thin echogenic line and possible hematoma deep to the skin or Buck’s fascia (Fig. 9). Approximately 10–20% of penile fractures are associated with urethral injury, especially if both cavernosa are disrupted, and therefore retrograde urethrography should also be performed when the diagnosis is suspected [33].

Penile trauma/fracture. a Purplish turgidity of the penis reminiscent of an eggplant in the setting of penile trauma and concern for fracture (case courtesy of Dr. Praveen Jha, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 25999). b Focal defect along the dorsal tunica albuginea with herniation of a portion of the corpora cavernosa (arrow), consistent with penile fracture

Scrotal wall

Fournier gangrene

Although CT is the imaging modality of choice for elucidating potential perineal infection and the extent of spread, superficial necrotizing fasciitis of the perineum can present as scrotal tenderness or swelling and therefore ultrasound may be the initial imaging study performed. Sonographically, multiple echogenic foci (representing gas) with areas of dirty shadowing may be identified within the scrotal wall (Fig. 10). This should raise suspicion for gas forming soft tissue infection and prompt surgical consultation [1, 34].

Cellulitis

In contrast to Fournier gangrene, cellulitis is a nonnecrotizing infection of the subcutaneous tissues, hypodermic and superficial fascia, without extension to the muscle or deep fascial planes [35, 36]. On physical exam, there may be erythema, swelling, and warmth of the skin. Sonographically, this manifests as subcutaneous reticulation and edema. There may be associated localized superficial fluid collections.

3rd spacing (CHF, etc.)

Diffuse symmetric scrotal skin thickening/edema can be seen in generalized anasarca or volume overload states due to a systemic process such as congestive heart failure, sepsis, etc.

Referred pain

Urinary tract stone/hydroureter

Urinary tract calculi, especially of the distal lower tract, may result in referred pain to the ipsilateral inguinoscrotal region. Therefore, selective assessment of the ureterovesical junctions and bladder for the presence of stones is reasonable if the patient presents with colicky pain, history of urolithiasis, and no evident penoscrotal cause (Fig. 11).

Urinary tract calculi. a Echogenic focus at the right ureterovesical junction (arrow) in patient with history of renal stones and right scrotal pain. Scrotal exam was normal. A 3-mm calculus was strained from the urine a day after presentation. b Echogenic calculus (arrow) within the prostatic urethra near the bladder base of a 4-year-old male with sickle cell disease and right groin pain. (P, prostate). Per patient’s mother, a calculus soon passed

Conclusion

Timely diagnosis of male genitourinary emergencies is aided by careful sonographic examination of the scrotal contents. While testicular torsion and epididymo-orchitis are two of the most common and grave scrotal emergencies, other critical diagnoses must be considered. Torsed testicular appendages, penile and testicular trauma, and para- and intratesticular mimics often have unique sonographic findings that facilitate their diagnoses (Table 1).

References

Avery LL, Scheinfeld MH (2013) Imaging of penile and scrotal emergencies. Radiographics 33:721–740

Dogra VS, Gottlieb RH, Oka M, Rubens DJ (2003) Sonography of the scrotum. Radiology 227(1):18–36

Remer EM, Casalino DD, Arellano RS, Bishoff JT, Coursey CA, Dighe M, Fulgham P, Israel GM, Lazarus E, Leyendecker JR, Majd M, Nikolaidis P, Papanicolaou N, Prasad S, Ramchandani P, Sheth S, Vikram R, Karmazyn B (2012) ACR appropriateness criteria acute onset of scrotal pain - without trauma, without antecedent mass. Ultrasound Q 28:47–51

Ragheb D, Higgins JL Jr (2002) Ultrasonography of the scrotum: technique, anatomy, and pathologic entities. J Ultrasound Med 21:171–185

Sung EK, Setty BN, Castro-Aragon I (2012) Sonography of the pediatric scrotum: emphasis on the Ts—torsion, trauma, and tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol 198(5):996–1003

Dudea SM, Ciurea A, Chiorean A, Botar-Jid C (2010) Doppler applications in testicular and scrotal disease. Med Ultrason 12(1):43–51

Sparano A, Acampora C, Scaglione M, Romano L (2008) Using color power Doppler ultrasound imaging to diagnose the acute scrotum: a pictorial essay. Emerg Radiol 15(5):289–294

Hamper UM, DeJong MR, Caskey CI, Sheth S (1997) Power Doppler imaging: clinical experience and correlation with color Doppler US and other imaging modalities. Radiographics 17(2):499–513

Aso C, Enriquez G, Fite M et al (2005) Gray-scale and color Doppler sonography of scrotal disorder in children: an update. Radiographics 25:1197–1214

Monga M, Scarpero HM, Ortenberg J (1999) Metachronous bilateral torsion of the testicular appendices. Int J Urol 6:589–591

Singh AK, Kao SCS (2010) Torsion of testicular appendage. Pediatr Radiol 40:373

Strauss S, Faingold R, Manor H (1997) Torsion of the testicular appendages: sonographic appearance. J Ultrasound Med 16:189–192

Konicki PJ, Baumgartner J, Kulstad EB (2004) Epididymal abscess. Am J Emerg Med 22(6):505–506

Bhatt D, Dogra VS (2008) Role of US in testicular and scrotal trauma. Radiographics 28(6):1617–1629

Guichard G, El Ammari J, Del Coro C et al (2008) Accuracy of ultrasonography in diagnosis of testicular rupture after blunt scrotal trauma. Urology 71(1):52–56

Dogra V, Bhatt S (2004) Acute painful scrotum. Radiol Clin N Am 42:349–363

Deurdulian C, Mittelstadt CA, Chong WK, Fielding JR (2007) US of acute scrotal trauma: optimal technique, imaging findings, and management. Radiographics 27:357–369

Siegel MJ (1997) The acute scrotum. Radiol Clin N Am 35(4):959–976

Buckley JC, McAninch JW (2006) Diagnosis and management of testicular ruptures. Urol Clin N Am 33(1):111–116

Phonsombat S, Master VA, McAninch JW (2008) Penetrating external genitalia trauma: a 30-year single institution experience. J Urol 180(1):192–196

Cline KJ, Mata JA, Venable DD, Eastham JA (1998) Penetrating trauma to the male external genitalia. J Trauma 44(3):492–494

Mehta AL, Dogra VS (1998) Intratesticular varicocele. J Clin Ultrasound 26:49–51

Das KM, Prasad K, Szmigielski W, Noorani N (1999) Intratesticular varicocele: evaluation using conventional and Doppler sonography. AJR 172:1079–1083

Garriga V, Serran A, Marin A et al (2009) US of the tunica vaginalis testis: anatomic relationship and pathologic conditions. Radiographics 29:2017–2032

Zagoria R, Dyer R, Brady C (2016) Genitourinary imaging: the requisites, 3rd edn. Elsevier, Philadelphia. The Male Genital Tract. p 304–336

Revzin MV, Ersahin D, Israel G et al (2016) US of the inguinal canal: comprehensive review of pathologic processed with CT and MR imaging correlation. Radiographics 36:2028–2048

Joshi S, Mansour AM, Edefrawy A, Soloway MS (2012) Diffuse large B cell lymphoma of the spermatic cord: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Urol 19:6581–6583

Yang DM, Kim HC, Lee HL, Lim JW, Kim GY (2010) Sonographic findings of acute vasitis. J Ultrasound Med 29(12):1711–1715

Chan PT, Schegel PN (2002) Inflammatory conditions of the male excurrent ductal system. J Androl 23(4):453–460

Martin LC, Share JC, Peters C, Atala A (1996) Hydrocele of the spermatic cord: embryology and ultrasonographic appearance. Pediatr Radiol 26:528–530

Sawh SL, O’Leary MP, Ferreira MD et al (2008) Fractured penis: a review. Int J Impot Res 20(4):366–369

Bitsch M, Kromann-Andersen B, Schou J, Sjontoft E (1990) The elasticity and the tensile strength of tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. J Urol 143(3):642–645

Hoag NA, Hennessey K, So A (2011) Penile fracture with bilateral corporeal rupture and complete urethral disruption: case report and literature review. Can Urol Assoc J 5(2):E23–E26

Levenson RB, Singh AK, Noveline RA (2008) Fournier gangrene: role of imaging. Radiographics 28(2):519–528

Hayeri MR, Ziai P, Shehata ML, Teytelboym OM, Huang BK (2016) Soft-tissue infections and their imaging mimics: from cellulitis to necrotizing fasciitis. Radiographics 36:1888–1910

Soldatos T, Durand DJ, Subhawong TK, Carrino JA, Chhabra A (2012) Magnetic resonance imaging of musculoskeletal infections: systematic diagnostic assessment and key points. Acad Radiol 19(11):1434–1443

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author A declares that he has no conflict of interest. This work was performed while a resident at Wake Forest University. The author is currently a fellow at Emory University.

Author B has no conflict of interest. The author is an advisor for Enlitic. (10 Jackson St. San Francisco, CA 94111) and an employee of the Department of Veterans Affairs National Teleradiology Program.

Ethical approval

All images in this manuscript were of studies performed for clinical purposes and incorporated into the manuscript via retrospective review. All patient identification information has been removed. Otherwise, this article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McAdams, C.R., Del Gaizo, A.J. The utility of scrotal ultrasonography in the emergent setting: beyond epididymitis versus torsion. Emerg Radiol 25, 341–348 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-018-1606-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10140-018-1606-y