Abstract

Background

The pattern of venous drainage of head and neck involves single external jugular vein bilaterally.

Methods and results

We report a case of bifurcation of the external jugular vein observed during a neck dissection procedure.

Conclusions

Anatomical variations in drainage pattern of superficial veins of the head and neck are important for head and neck surgeries including for anastomosis during free tissue transfer for head and neck reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Posterior retromandibular and posterior auricular vein join to form external jugular vein (EJV) which descends in superficial fascia deep to the platysma to enter posterior triangle, where it pierces investing layer of deep fascia and ends in to subclavian vein.

The complex embryologic development of vascular system often results in clinically relevant anomalies. The relevance and importance of varied drainage pattern are important for their use in surgeries involving microvascular anastomosis.

Case report

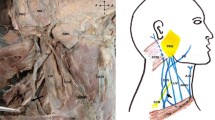

A 48-year-old male patient diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma of right buccal mucosa underwent modified radical neck dissection; while the subplatysmal flap was raised, two parallel veins were identified in superficial fascia of the neck (Fig. 1). Both originated from within the deep lobe of parotid gland and followed a course lateral to sternocleidomastoid and joined as a single vein of large calibre before penetrating deep fascia inferiorly. Based upon anatomical similarities with usual description of the EJV, the vessels were confirmed as bifurcated external jugular vein. The calibre of both veins was greater than normal and found equal in comparison with internal jugular vein (IJV). Coincidentally, all other vessels and muscles like the omohyoid had a larger calibre and size as compare to the normal.

Discussion

Numerous anatomical variations of external jugular vein have been reported in literature. Hollinshead reported that in one third of cases the external jugular vein drains into the internal jugular vein [1]. Lalwani et al. reported an unusual venous communication of the external jugular vein of one side, into the internal jugular vein of the opposite side [2]. Keith R. Reinhardt reported an anomalous EJV coursing anterior to the clavicle [3]. Shima et al. have described two types of external jugular vein, in which type 2 begins as two veins in cranial part of the neck and join along posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid to form single vein [4]. Although there appears several reported cases of anomalies in EJV, we found only one reported case of EJV duplication in the literature. Ela Comert reported a case of duplication of EJV which started as a single vein but divided in its course to again join into a single vein before piercing the deep facia [5].

The literature search did not find any reported case of excessive calibre of the EJV which was equivalent to IJV in our case. Abnormal calibre of the veins could be critical factor for intraoperative blood loss; Keith R. Reinhardt cautioned about inadvertent injury to anomalous vascular structures which can be devastating to the patient and suggested that such complications should be avoided by careful surgical approaches [3]. In present study, we observed bifurcated EJV running close to each other with large calibre as comparable to the IJV. Though EJV is considered less reliable than IJV owing to many risk factors including small calibre, we found in our case favourable calibre and geometry suitable for anastomosis. Such variation of EJV should alarm the surgical team of other possible variations in vascular anatomy.

Conclusion

Awareness of such anatomical variation is important before any surgical interventions of the head and neck. A keen study of pre-operative contrast enhanced computed tomography of the head and neck can be helpful in planning to manage such anatomical variation.

References

Hollinshead WH (William H. Anatomy for surgeons) [Internet]. Harper & Row; 1982 [cited 2018 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog

Lalwani R, Rana KK, Das S, Khan RQ (2006) Communication of the external and internal jugular veins: a case report | Comunicación entre las venas yugulares externa e interna: Reporte de caso. Int J Morphol 24(4):721–722

Reinhardt KR, Kim HJ, Lorich DG (2011) Anomalous external jugular vein: clinical concerns in treating clavicle fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 131(1):1–4

Shima H, von Luedinghausen M, Ohno K, Michi K (1998) Anatomy of microvascular anastomosis in the neck. Plast Reconstr Surg 101(1):33–41 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9427914

Comert E, Comert A. External jugular vein duplication. J Craniofac Surg. 2009 20(6):2173–4. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00001665-200911000-00045

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure

No grant was obtained in preparation of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, S., Pandey, S., Kumar, Y. et al. Bifurcation of external jugular vein: an anatomical variation during neck dissection. Oral Maxillofac Surg 22, 475–476 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-018-0717-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-018-0717-7