Abstract

Objectives

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is a very common oral mucosal disease, and its management is quite challenging with no definitive cure being available so far. Many studies have tried hyaluronic acid (HA) for alleviating signs and symptoms of RAS. The present systematic review sought to assess the available evidence regarding the efficacy of HA in management of RAS.

Methods

Two reviewers independently conducted extensive search in four online databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and the gray literature, with no restriction to date or language of the publication. All clinical trials that assessed the efficacy of HA in reducing signs and symptoms of RAS were included. Risk of bias was assessed by two reviewers independently, using the Cochrane assessment tool. Due to substantial heterogeneity, no meta-analysis was feasible.

Results

Out of the 75 identified articles, nine clinical trials involving 538 RAS patients (259 in HA group) were included. The risk of bias was high in five studies, low in one study, and unclear in three studies. The comparative groups varied greatly across the included studies: triamcinolone (in three studies), chlorhexidine mouthwash, lidocaine, placebo, iodine glycerin, diclofenac, and laser therapy. Overall, the results revealed a good efficacy of HA in alleviating pain and shortening the healing time of RAS, without any reported side effects. Compared to triamcinolone, HA showed superior results in one study, and comparable results in two studies.

Conclusions

The available evidence suggests that HA is a promising treatment option for RAS. However, given the huge heterogeneity of the included studies and high risk of bias in some of these studies, the evidence is inconclusive. Further well-designed clinical trials with standardized methodologies and adequate sample sizes are warranted to discern the efficacy of HA for RAS.

Clinical relevance

Hyaluronic acid might be a viable alternative therapeutic option for patients with RAS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is an oral mucosal ulcerative disease characterized by recurring episodes of small ulcers, affecting mainly the non-keratinized mucosa [1, 2]. These ulcers are usually associated with severe pain and discomfort that interfere with oral functions such as eating, drinking, and speaking, thus adversely affecting the patients’ quality of life [3]. RAS is a highly prevalent disease afflicting up to 25% of the general population, with no gender predilection [2, 4]. Typically, it is a disease of adolescents and young adults, although the disease can affect any age group[4]. By and large, the etiopathogenesis of RAS is not yet clear [1, 2]. Some predisposing factors have been suggested including, but not limited to, immunological dysfunction, hematologic factors, stress, trauma, hormonal changes, genetic factors, and minerals and/or vitamin deficiencies [5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, recent evidence suggests that immunological mechanisms (both humoral and cellular) have an essential role in the etiopathogenesis of RAS [7, 8, 11].

Given the obscure etiopathogensis, there is no effective therapy available thus far [1]. Hence, the current management strategy aims primarily at alleviating pain, shortening the healing time, and reducing the frequency rates of new episodes [1, 12, 13]. In context of the latter, various topical medicaments have been used for management of RAS: corticosteroids, salicylic acid, antiseptic mouthwashes, analgesics, anesthetics, antibiotics, antioxidants like N-acetylcysteine, and various herbal remedies, with limited success [12, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. In severe RAS cases like more frequent attacks (commonly known as called complex aphthosis) and/or refractory major RAS, more potent systemic medications such as systemic corticosteroids, colchicine, pentoxyfilline, and thalidomide are used [20, 21]; however, these medications are associated with serious side effects, a matter that limits their use [20]. In principle, topical corticosteroids are the most widely prescribed medication for RAS patients, although they have limited efficacy [18], especially in reducing the healing time, and are associated with numerous side effects such as opportunistic fungal infections, thinning of the mucosa in addition to patients’ incompliance [12, 14].

Hyaluronic acid (HA), also known as Hyaluronan, has recently been introduced for the management of various oral and systemic inflammatory conditions with very promising results [22, 23]. HA is a carbohydrate component of the extracellular matrix that is available naturally in many tissues and body fluids [23]. It has been reported to have strong wound healing properties, probably through moderation of the inflammatory responses, promoting cell proliferation, and promoting re-epithelization via the proliferation of basal keratinocytes [23,24,25,26]. Additionally, many studies ascertained the analgesic and potent anti-inflammatory effects of HA [27, 28]. Such properties rendered HA a good candidate for management of various systemic and oral inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis, temporomandibular joint disorders (TMJ), dry socket, skin disorders, leg ulcers, lichen planus, and recurrent oral ulcers [24, 27, 29,30,31,32]. In this regard, a number of clinical trials have tried topical HA for management of RAS, and reported conflicting results, although promising to a large extent compared to the current medications [33,34,35,36,37,38]. Hence, the present systematic review sought to assess the available evidence regarding the efficacy of topical HA for reducing signs and symptoms of RAS.

Methods

Study protocol and focused question

The protocol of the present systematic review was registered by PROSPERO (Reg. #: CRD42021259970), and was performed in full adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [39]. The addressed PICOS (Participants, Intervention, Control, Outcomes and Study design) question was: “Is topical hyaluronic acid (HA) efficient in the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS)?”.

Eligibility criteria

The PICOS eligibility criteria applied in this review were as follows:

Participants (P): healthy individuals diagnosed with RAS; Intervention (I): topical HA; Comparator (C): any medical intervention or placebo controls; Outcomes (O): pain, healing time and/or size of the ulcers were studied as the primary outcomes, whereas side effects of the intervention were considered as additional outcomes; and Study design (S): randomized (RCT) and non-randomized controlled clinical trials (nRCT). Retrospective and prospective observational studies, case series, case reports, animal studies, review papers, editorials, letters to the editor, commentary, and monographs were excluded.

Literature search strategy

Two authors (NA and RH) performed an independent and thorough search in four databases (MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar) and the gray literature (through Proquest) on 25 June, 2021 for all relevant published studies. The search was neither date- nor language-restricted. Different combinations of the following keywords/terms were used: hyaluronic acid; hyaluronan; aphthous stomatitis; recurrent aphthous stomatitis; recurrent aphthous ulcers; recurrent oral ulcers; and canker sores (Table 1). All identified articles were retrieved to an endnote program, and duplicates were removed. These two authors screened the articles independently through reading the titles and abstracts; the irrelevant studies were excluded. The full-texts of all potentially eligible studies were screened for inclusion. The reference lists of the retrieved studies were also hand-searched for any additional studies. In case of any disagreements, a third reviewer was consulted. Authors of the included studies were contacted in case of missing data or for any clarification.

Quality assessment

Assessment of risk of bias was carried out independently by two reviewers (NA and SA) using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool [40]. Disagreements, if any, were resolved by discussion and/or by consulting a third reviewer. According to the above mentioned tool, seven domains were evaluated: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. Accordingly, each study was graded as low, all items were of low risk; unclear, at least one item was evaluated to be of unclear risk but no item of high risk; or high, at least one item with high risk of bias [40].

Data extraction

Two reviewers (RH and SA) independently extracted all relevant data: study details (author, year of publication, and country of the study), study design, comparison groups, demographics of the participants (sample size, age, and gender), formulation and dosage of HA and the comparative interventions, primary and secondary outcomes measures (i.e., pain, ulcer size, healing time, and side effects), and the main findings.

Statistical analysis

The initial aim was to pool the results and quantify the effect size using the meta-analysis approach. However, the substantial heterogeneity among the included studies along with missing of numerical data in some of these studies precluded us from conducting the meta-analysis. Hence, the included studies were qualitatively analyzed.

Results

Search strategy results

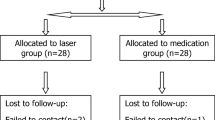

Figure 1 depicts the results of the online search. Around 75 studies were found of which 33 were duplicates and thus removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 42 studies were screened by two independent reviewers and 20 studies were excluded as irrelevant. The full-texts of the remaining 24 articles were reviewed by the two independent reviewers, and 15 studies were excluded due to various reasons (Supplementary Table 1). The remaining nine studies [33,34,35,36,37,38, 41,42,43] fulfilled the eligibility criteria and thus were included in the subsequent qualitative analysis, and the relevant data were extracted.

General characteristics of the included studies

Table 2 presents the general characteristics of the included studies. Eight RCT [33, 35,36,37,38, 41,42,43] and one non-randomized clinical trial [34] comprising 538 RAS patients (259 in HA group and 279 in the control group) were included. Three studies were conducted in Egypt [33, 37, 38], two in Iraq [34, 36], one in China [43], one in the UK [42], one in USA [41], and one in Turkey[35]. Number of RAS patients ranged from 25 [34] to 116 individuals [42], with a range of mean of age from 4 ± 6.8 to 45.5 years. All studies except one [37] reported gender of the included participants; around half of the subjects were females. With regards to type of RAS, five studies [33, 34, 37, 38, 41] recruited minor RAS, one study [36] recruited both minor and major RAS cases, while three studies didn’t report the type of RAS [35, 42, 43]. All studies reported diagnosis of RAS based on clinical features and history of the same, and excluded patients with systemic diseases that may cause RAS-like lesions (Table 2).

Outcome measures

All studies assessed the efficacy HA in reducing pain as one of the main outcomes; seven studies [34,35,36, 38, 41,42,43] used the visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain assessment, one study used Wong- Baker faces rating Scale [37], while one study [33] did not provide any information in this regard. Five studies [34, 36,37,38, 41] assessed the efficacy of HA on ulcer size. Two studies [33, 38] measured the healing time in days. Two studies [42, 43] measured the number of ulcers, incidence of new ulcers and ulcer-free patients (Table 2).

Intervention and comparison groups

HA was used as gel in seven studies [33, 35,36,37, 41,42,43], as mouthwash (10 ml Hyaloronan sodium 25 mg/100 ml) in one study [38], and as spray (0.01% HA) in one study [34]. With regard to HA gel, only five studies [33, 36, 37, 41, 42] reported HA concentration, that ranged from 0.2 to 2.5%: 0.2% in three studies [36, 37, 42], 2% in one study [33]; 2.5% in one study [41].

The comparative groups varied greatly across the studies: triamcinolone in three studies [34,35,36], chlorhexidine mouthwash [38], lidocaine gel [41], placebo gel [42], iodine glycerin gel [43], Diclofenac in 2% HA base gel [33], and single application of Diode laser therapy [37]. Except for Saxen study [41], which did not provide any information, the reported duration of HA application varies from 5–11 days, with the most frequent duration was 7 days (Table 2).

Main qualitative results

As shown in Table 3, all studies reported comparable-to-superior pain-reduction efficacy in favor of HA compared to the different interventions assessed, except for one study [37], which reported inferior pain-reduction effect of HA in comparison to Diode laser. With regard to the gold standard comparative intervention (Triamcinolone acetonide), Mustafa et al. [36] reported better efficacy in reducing pain in favor of HA, while two studies by Koray et al. [35] and Hamed [34] reported comparable efficacy of both interventions except on the fourth and seventh days in Koray study [35] and second day in Hamed study [35] where HA was more efficacious in reducing pain.

With regard to HA effects on ulcer size, five studies reported on this outcome and found variable results: one study [36] found superior efficacy in favor of HA as compared to Triamciolone acetonide; one study [37] reported inferior results in HA group compared to the control group ( single session of Diode laser application); and three studies [34, 38, 41] reported comparable results (Table 2). Concerning the efficacy of HA on ulcer healing, one study[38] reported better efficacy in HA group compared to control group, while one study found a comparable efficacy [33]. Number of ulcer/ulcer-free patients and occurrence of new ulcers were found to be significantly lower with application of HA compared to placebo [42, 43] (Table 3).

Side effects

Six studies [33, 35,36,37,38, 41] asserted that HA is safe as they did not find any side effects secondary to its use, while three studies [34, 42, 43] did not provide any information about the side effects (Table 3).

Quality of the included studies

Table 4 summarizes the results of quality appraisal of the included studies. Five studies were graded as high risk of bias [34,35,36, 38, 43], one study was graded as low risk of bias [41], while three studies [33, 37, 42] were of unclear risk of bias. The most frequent methodological flaws were related to the criteria of “Blinding of participants” and “Blinding of outcome” (Table 4).

Discussion

RAS is associated with significant pain and discomfort that negatively impact the patients’ quality of life [1, 3]. Unfortunately, irrespective of the high prevalence of, and the huge research conducted on RAS, its management is still quite challenging with no definitive cure [1]. HA is gaining ground as a treatment modality for RAS and other oral and systemic inflammatory conditions [24, 25, 27, 31]. In confirmation of the above, the results of the current systematic review revealed good efficacy for HA in reducing pain and speeding the healing time in RAS patients. Additionally, the results revealed that topical application HA is safe with a good patient’s compliance. Nevertheless, apart from the positive results reported in this review, they should be interpreted with caution due to the substantial heterogeneity among the studies and some methodological shortcomings in some of the included studies.

The main finding of the present systematic review is the positive effects of HA in reducing RAS-associated pain. The clinical efficacy of HA in reliving RAS symptoms can be attributed to its analgesic and potent anti-inflammatory properties [27, 28]. To elaborate, HA inhibits inflammation through regulating the inflammatory mediators associated with nociceptive pain such as prostaglandin E2, cyclooxygenase-2, and adenosine 5-triphosphate, a fact that may explain the potent and immediate analgesic effects of HA [28]. Actually, this result is in line with the findings of many previous studies that reported positive effects of topical HA application in alleviating pain and other inflammation-associated symptoms in a number of oral and systemic disorders such as, disorders of temporomandibular joint, arthritis, oral lichen planus, and radiation-induced oral mucositis [22, 27, 30, 31, 44]. Additionally, many case series and retrospective studies (not included in the present review) showed a good efficacy of HA in reducing signs and symptoms of RAS [45,46,47], which further substantiate the findings of the present review.

Another main finding of the present review is a good efficacy of HA in reducing the healing time of RAS: It was found to be as efficacious as or even better than triamcinolone. This can be ascribed to the strong wound-healing properties of HA [25, 26]. In fact, the hygroscopic and viscoelastic properties of HA play an important role in the wound healing process [23, 26, 30]. Further, HA has been reported to promote wound healing and re-epithelization through proliferation of basal keratinocytes and reduction of collagen disposition and scarring [22, 23].

Two important aspects of the management of RAS are the safety and patient compliance. Although it is the case with any disease, it must be emphasized more specifically with RAS given the recurrence nature of the disease and the need for long-term use of various therapies in some cases. The secondary outcome assessed in this review was the side effects associated with HA. The results of the current review showed that topical application of HA is safe and well-tolerated, rendering HA a feasible alternative therapeutic option for RAS. Another important advantage of topical HA is the fact that it is available over-the counter and can be used safely by all individuals including small children and pregnant women without any complications or drugs interactions [23, 42]. Customarily, topical corticosteroids— the most widely used medicaments for RAS—are associated with many local and systemic adverse effects limiting their use [42]. The results of the present systematic review corroborate previous studies that reported HA to be safe and well tolerated [23, 24, 32, 44, 48]. Another concern of the current RAS therapeutics is the cost of treatment, considering the chronic and recurrent nature of RAS, which necessitates long term treatment, resulting in a terrible financial impact on patients, especially in low-income countries [14]. Hence, a safe, efficacious, and cost-effective medicament like topical HA might be a viable alternative option for the management of RAS [48, 49].

The present systematic review has some weaknesses that limit its results. The key limitation is the low quality of some of the included studies as evident by the high risk of bias, a matter that weakens the evidence obtained from this review. Another key limitation is the marked heterogeneity among the included studies in different parameters such as comparison groups, outcome measures, formulation and dose of the intervention, duration of therapy, type of RAS, and age and gender of the participants. The heterogeneity in the comparison groups in particular made the inter-studies comparability very impossible, and thus no firm conclusion can be drawn. A further limitation was related to the discrepancy in the reported outcomes along with missing numerical data in some of the included studies, a matter that hindered us from pooling the data and thus no meta-analysis was conducted. However, despite these limitations, this review has some strengths that should be recognized. First, this is the first systematic review that evaluated the evidence regarding HA efficacy for RAS. Second, the study extensively searched the literature without any language restriction, and thus no potential studies might have been missed. Third, the review included a relatively good number of studies with a fairly good sample size (9 clinical studies involving 538 RAS patients) from different geographical regions and that somewhat substantiates the concluded evidence.

In conclusion, the available evidence suggests the potentially positive efficacy of HA in reducing signs and symptoms associated with RAS. Further, well-designed studies with large sample sizes and standardized methodologies are needed to confirm the efficacy of HA.

References

Saikaly SK, Saikaly TS, Saikaly LE (2018) Recurrent aphthous ulceration: a review of potential causes and novel treatments. J Dermatolog Treat 29:542–552. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2017.1422079

Tarakji B, Gazal G, Al-Maweri SA, Azzeghaiby SN, Alaizari N (2015) Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis for dental practitioners. J Int Oral Health 7:74–80

Yang C, Liu L, Shi H, Zhang Y (2018) Psychological problems and quality of life of patients with oral mucosal diseases: a preliminary study in Chinese population. BMC Oral Health 18:226. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0696-y

Al-Johani K (2019) Prevalence of recurrent aphthous stomatitis among dental students: a cross sectional study. J Contemp Dent Pract 20:893–895

Al-Maweri SA, Halboub E, Al-Sharani H, Shamala A, Al-Kamel A, Al-Wesabi M, Albashari A, Al-Sharani A, Abdulrab S (2020) Association between serum zinc levels and recurrentaphthous stomatitis: a meta-analysis with trial sequentialanalysis. Clin Oral Investig 25(2):407–415

Al-Maweri SA, Halboub E, Al-Sufyani G, Alqutaibi AY, Shamala A, Alsalhani A (2019) Is vitamin D deficiency a risk factor for recurrent aphthous stomatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13189

Mohammad R, Halboub E, Mashlah A, Abou-Hamed H (2013) Levels of salivary IgA in patients with minor recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a matched case-control study. Clin Oral Investig 17:975–980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-012-0785-2

Ruan HH, Li GY, Duan N, Jiang HL, Fu YF, Song YF, Zhou Q, Wang X, Wang WM (2018) Frequencies of abnormal humoral and cellular immune component levels in peripheral blood of patients with recurrent aphthous ulceration. J Dent Sci 13:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2017.09.003

Shen C, Ye W, Gong L, Lv K, Gao B, Yao H (2021) Serum interleukin-6, interleukin-17A, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 50:418–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.13158

Xu K, Zhou C, Huang F, Duan N, Wang Y, Zheng L, Wang X, Wang W (2021) Relationship between dietary factors and recurrent aphthous stomatitis in China: a cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res 49:3000605211017724. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211017724

Ozyurt K, Celik A, Sayarlıoglu M, Colgecen E, Incı R, Karakas T, Kelles M, Cetin GY (2014) Serum Th1, Th2 and Th17 cytokine profiles and alpha-enolase levels in recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 43:691–695. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12182

Al-Maweri SA, Alaizari N, Alharbi AA, Alotaibi SA, AlQuhal A, Almutairi BF, Alhuthaly S and Almutairi AM (2020) Efficacy of curcumin for recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1819529

Halboub E, Al-Maweri SA, Parveen S, Al-Wesabi M, Al-Sharani HM, Al-Sharani A, Al-Kamel A, Albashari A, Shamala A (2021) Zinc supplementation for prevention and management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review. J Trace Elem Med Biol Organ Soc Miner Trace Elem (GMS) 68:126811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126811

Al-Maweri SA, Halboub E, Ashraf S, Alqutaibi AY, Qaid NM, Yahya K, Alhajj MN (2020) Single application of topical doxycycline in management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available evidence. BMC Oral Health 20:231. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01220-5

El-Haddad SA, Asiri FY, Al-Qahtani HH, Al-Ghmlas AS (2014) Efficacy of honey in comparison to topical corticosteroid for treatment of recurrent minor aphthous ulceration: a randomized, blind, controlled, parallel, double-center clinical trial. Quintessence Int (Berlin, Germany: 1985) 45:691–701. https://doi.org/10.3290/j.qi.a32241

Yarom N, Zelig K, Epstein JB, Gorsky M (2017) The efficacy of minocycline mouth rinses on the symptoms associated with recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized, double-blind, crossover study assessing different doses of oral rinse. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 123:675–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oooo.2017.02.013

Lu J, Zhang N, Qian W (2020) The clinical efficacy and safety of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a protocol of systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 99:e22588. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000022588

Hamishehkar H, Nokhodchi A, Ghanbarzadeh S, Kouhsoltani M (2015) Triamcinolone acetonide oromucoadhesive paste for treatment of aphthous stomatitis. Adv Pharm Bull 5:277–282. https://doi.org/10.15171/apb.2015.038

Halboub E, Alkadasi B, Alakhali M, AlKhairat A, Mdabesh H, Alkahsah S and Abdulrab S (2019) N-acetylcysteine versus chlorhexidine in treatment of aphthous ulcers: a preliminary clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2019.1688231

Brocklehurst P, Tickle M, Glenny AM, Lewis MA, Pemberton MN, Taylor J, Walsh T, Riley P and Yates JM (2012) Systemic interventions for recurrent aphthous stomatitis (mouth ulcers). Cochrane Database Syst Rev:Cd005411. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005411.pub2

Zeng Q, Shi X, Yang J, Yang M, Zhao W, Zhao X, Shi J, Zhou H (2020) The efficacy and safety of thalidomide on the recurrence interval of continuous recurrent aphthous ulceration: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 49:357–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/jop.12960

Chen LH, Xue JF, Zheng ZY, Shuhaidi M, Thu HE, Hussain Z (2018) Hyaluronic acid, an efficient biomacromolecule for treatment of inflammatory skin and joint diseases: a review of recent developments and critical appraisal of preclinical and clinical investigations. Int J Biol Macromol 116:572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.068

Salwowska NM, Bebenek KA, Żądło DA, Wcisło-Dziadecka DL (2016) Physiochemical properties and application of hyaluronic acid: a systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol 15:520–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.12237

Casale M, Moffa A, Sabatino L, Pace A, Oliveto G, Vitali M, Baptista P, Salvinelli F (2015) Hyaluronic acid: perspectives in upper aero-digestive tract. A systematic review. PloS one 10:e0130637. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130637

Graça MFP, Miguel SP, Cabral CSD, Correia IJ (2020) Hyaluronic acid-based wound dressings: a review. Carbohyd Polym 241:116364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116364

Wu S, Deng L, Hsia H, Xu K, He Y, Huang Q, Peng Y, Zhou Z, Peng C (2017) Evaluation of gelatin-hyaluronic acid composite hydrogels for accelerating wound healing. J Biomater Appl 31:1380–1390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885328217702526

Iturriaga V, Bornhardt T, Manterola C, Brebi P (2017) Effect of hyaluronic acid on the regulation of inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 46:590–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2017.01.014

Yasuda T (2010) Hyaluronan inhibits prostaglandin E2 production via CD44 in U937 human macrophages. Tohoku J Exp Med 220:229–235. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.220.229

Casale M, Moffa A, Vella P, Rinaldi V, Lopez MA, Grimaldi V, Salvinelli F (2017) Systematic review: the efficacy of topical hyaluronic acid on oral ulcers. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 31:63–69

Dubovina D, Mihailović B, Bukumirić Z, Vlahović Z, Miladinović M, Miković N, Lazić Z (2016) The use of hyaluronic and aminocaproic acid in the treatment of alveolar osteitis. Vojnosanit Pregl 73:1010–1015. https://doi.org/10.2298/vsp150304125d

Hashem AS, Issrani R, Elsayed TEE, Prabhu N (2019) Topical hyaluronic acid in the management of oral lichen planus: A comparative study. J Investig Clin Dent 10:e12385. https://doi.org/10.1111/jicd.12385

Jacobus Berlitz S, De Villa D, MaschmannInacio LA, Davies S, Zatta KC, Guterres SS, Külkamp-Guerreiro IC (2019) Azelaic acid-loaded nanoemulsion with hyaluronic acid–a new strategy to treat hyperpigmentary skin disorders. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 45:642–650

Fariba I, Taghi G, Mazdak E, Maryam T, Hossein S, Shahla E, Zabiholah S (2005) The efficacy of 3% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel base for treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS): A double blind study. Egypt Dermatol Online J 1:4

Hamed GY (2015) The efficacy of hyaluronic acid spray in treatment of recurrent aphthus ulcer. Int J Enhanc Res Sci Technol Eng 4:82–86

Koray M, Ofluoglu D, Senemtasi A, İşsever H, Yaltirik M (2016) The efficacy of hyaluronic acid gel in pain control of recurrent Aphthous stomatitis. Int J Dent Oral Sci 3:273–275

Mustafa BN, Alzubaidee AF (2020) Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of topical hyaluronic acid (0.2%) and topical triamcinolone acetonide (0.1%) in the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Diyala J Med 19:107–117

Shalaby HKM (2019) Effect of diode laser combined with hyaluronic acid gel in treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in children: randomized clinical trial. Egypt Dent J 65:3555–3566

Zakaria M, Abdelwhab A, Hassan S (2020) Effectiveness of topical hyaluronic acid versus chlorhexidine mouthwashes in the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a randomized clinical trial. Egypt Dent J 66:1537–1543

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–9, w64. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA (2011) The Cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

Saxen MA, Ambrosius WT, al KF R, Russell AL, Eckert GJ (1997) Sustained relief of oral aphthous ulcer pain from topical diclofenac in hyaluronan: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 84:356–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90031-7

Nolan A, Baillie C, Badminton J, Rudralingham M, Seymour RA (2006) The efficacy of topical hyaluronic acid in the management of recurrent aphthous ulceration. J Oral Pathol Med Off Publ Int Assoc Oral Pathol Am Acad Oral Pathol 35:461–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00433.x

Tan R, D-m HU, K-e HU (2012) Study on the effect of hyaluronic acid on the treatment of recurrent oral ulceration. Chin J Aesthet Med 2012:14

Lopez MA, Manzulli N, D’Angelo A, Candotto V, Casale M, Lauritano D (2017) The use of hyaluronic acid as an adjuvant in the management of mucositis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 31:115–118

Lee JH, Jung JY, Bang D (2008) The efficacy of topical 0.2% hyaluronic acid gel on recurrent oral ulcers: comparison between recurrent aphthous ulcers and the oral ulcers of Behcet’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol: JEADV 22:590–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02564.x

Yang Z, Li M, Xiao L, Yi Z, Zhao M, Ma S (2020) Hyaluronic acid versus dexamethasone for the treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis in children: efficacy and safety analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res 53:e9886. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20209886

Dalessandri D, Zotti F, Laffranchi L, Migliorati M, Isola G, Bonetti S, Visconti L (2019) Treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS; aphthae; canker sores) with a barrier forming mouth rinse or topical gel formulation containing hyaluronic acid: a retrospective clinical study. BMC Oral Health 19:153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-019-0850-1

Romanò CL, De Vecchi E, Bortolin M, Morelli I, Drago L (2017) Hyaluronic acid and its composites as a local antimicrobial/antiadhesive barrier. J Bone Joint Infect 2:63–72. https://doi.org/10.7150/jbji.17705

Hatoum HT, Fierlinger AL, Lin SJ, Altman RD (2014) Cost-effectiveness analysis of intra-articular injections of a high molecular weight bioengineered hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis knee pain. J Med Econ 17:326–337. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2014.902843

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with humans or animals by any of the authors.

Consent to participate

Not required for this type of study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Maweri, S.A., Alaizari, N., Alanazi, R.H. et al. Efficacy of hyaluronic acid for recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review of clinical trials. Clin Oral Invest 25, 6561–6570 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04180-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-021-04180-4