Abstract

Purpose

The Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score, originally developed as a nutritional screening tool, is a cumulative score calculated from the serum albumin level, total cholesterol level, and total lymphocyte count. Previous studies have demonstrated that the score has significant prognostic value in various malignancies. We investigated the relationship between the CONUT score and long-term survival in obstructive colorectal cancer (OCRC) patients who underwent self-expandable metallic colonic stent placement and subsequently received curative surgery.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 57 pathological stage II and III OCRC patients between 2013 and 2019. The associations between the preoperative CONUT score and clinicopathological factors and patient survival were evaluated.

Results

A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis revealed that the optimal cut-off value for the CONUT score was 7. A CONUT score of ≥ 7 was significantly associated with elevated CA19-9 level (p = 0.03). Multivariate analyses revealed that a CONUT score of ≥ 7 was independently associated with cancer-specific survival (hazard ratio [HR] = 10.2, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–85.9, p = 0.03) and disease-free survival (HR = 7.1, 95% CI 2.3–21.7, p = 0.0006).

Conclusion

The results demonstrated that the CONUT score was a potent prognostic indicator. Evaluating the CONUT score might result in more precise patient assessment and tailored treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It has been increasingly recognized that nutritional status and systemic inflammatory response affect cancer progression. Malnutrition manifested as hypoalbuminemia is associated with poor long-term outcomes [1], and inflammation is considered one of the hallmarks of cancer [2]. The Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score, originally developed as a nutritional screening tool, is a cumulative score calculated from the serum albumin level, total cholesterol level, and total lymphocyte count. The score is easily calculated and was found to be significantly associated with the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) and Full Nutritional Assessment (FNA) [3]. Moreover, it was demonstrated to be associated with the prognosis and postoperative complications in a variety of malignancies [4,5,6,7,8].

Intestinal obstruction is one of the common presenting symptoms of colorectal cancer, with an incidence as high as 30% [9]. Obstructive colorectal cancer (OCRC) accounted for 85% of colonic emergency cases [10], which often required multiple-stage surgery accompanying high morbidity and stoma rate. Intestinal decompression using a self-expandable metallic colonic stent (SEMS) as “a bridge to surgery (BTS)” is now considered as an attractive alternative. Decompression allows bowel preparation, medical stabilization with correction of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities, and optimization of comorbid illnesses, which theoretically improves the patient’s nutritional and inflammatory status. It enables elective one-stage surgery with reduced morbidity and stoma rate compared to emergency surgery [11, 12]. Out of concern for short-term complications and long-term survival, SEMS was originally used with palliative intent [13] but has recently been used as a bridge to curative surgery.

The significant prognostic value of the CONUT score was demonstrated in colorectal cancer patients who underwent surgery [14,15,16,17,18] and those who received first-line chemotherapy [19]. However, the prognostic significance of the CONUT score in OCRC patients was unknown. Thus, in the present study, we investigated the prognostic value of the CONUT score in OCRC patients who underwent SEMS placement and subsequently received curative surgery.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 75 consecutive patients with pathological stage II and III OCRC who underwent SEMS placement as BTS at Sendai City Medical Center between 2013 and 2019. The patients had total or subtotal malignant colonic obstruction characterized by the following symptoms and findings: (1) obstructive symptoms, such as abdominal pain, fullness, vomiting, and constipation; (2) contrast-enhanced CT findings of colorectal tumor with dilation of the proximal bowel; and (3) severe stricture or obstruction demonstrated by contrast enema and colonoscopy. Patients were excluded if there were signs of peritonitis, perforation, or other serious complications demanding urgent surgery. Patients with benign disease, distant metastasis, positive surgical margin, and invasion from a non-colonic malignancy were excluded from the study. There were no patients with chronic inflammation. None of the patients received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy.

The severity of obstruction was evaluated using the ColoRectal Obstruction Scoring System (CROSS), which assigns a point score based on the patient’s oral intake level (Online Resource 1): CROSS 0, requiring continuous decompression; CROSS 1, no oral intake; CROSS 2, liquid or enteral nutrient intake; CROSS 3, soft solids, low-residue, and full diet with symptoms of stricture; and CROSS 4, soft solids, low-residue, and full diet without symptoms of stricture [20].

All patients subsequently underwent curative surgical resection. Postoperative complications were classified according to the Clavien–Dindo classification [21]. Pathological tumor staging was performed according to the AJCC cancer staging manual (7th edition) [22]. Colonic lesions proximal to the splenic flexure were defined as right-sided tumors.

The primary endpoint of the study was the long-term outcomes, which were defined as cancer-specific survival (CSS), and disease-free survival (DFS). CSS was measured from the date of the surgery to the date of death from recurrent cancer, and DFS was measured from the date of the surgery to the date of disease recurrence.

Laboratory tests were performed between stenting and surgery, and the CONUT score was calculated using the serum albumin concentration, peripheral lymphocyte count, and total cholesterol concentration (Online Resource 2). (1) Albumin concentrations of ≥ 3.5, 3.0–3.49, 2.5–2.99, and < 2.5 g/dL were scored as 0, 2, 4, and 6 points, respectively; (2) total lymphocyte counts of ≥ 1600, 1200–1599, 800–1199, and < 800/mm3 were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively; and (3) total cholesterol concentrations of ≥ 180, 140–179, 100–139, and < 100 mg/ dL were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3 points, respectively. The CONUT score was defined as the sum of (1), (2), and (3) [3].

Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± SD and were tested using Student’s t test. Associations between the CONUT score and clinicopathological parameters were evaluated in a cross-table using Fisher's exact test. The cut-off value was determined using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis using CSS as an end-point. The cut-off value was defined using the most prominent point on the ROC curve (Youden index = maximum [sensitivity‐(1‐specificity)]), and the area under the ROC (AUROC) curve was also calculated.

Survival curves were generated according to the Kaplan–Meier method and were analyzed by a log-rank test. A multivariate analysis was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Factors shown to have a p-value of < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. The T stage, N stage, venous invasion, and lymphatic invasion were incorporated into the analysis as potential confounding variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama medical center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statical Computing, Vienna, Austria); and P values of < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance [23].

Results

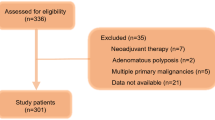

During the study period, there were 91 patients with pathological stage II and III OCRC who received curative surgery (Fig. 1). Eighty-two patients underwent elective surgery after endoscopic decompression. Among them, 75 patients underwent SEMS placement, and the remaining 7 patients were treated with a transanal decompression tube (TDT). Nine patients underwent emergency surgery including one patient with SEMS failure. Perforation occurred during guidewire manipulation for an 85-year-old female patient with transverse colon cancer who underwent Hartmann’s procedure in an emergent setting. Stenting-related complications were observed in two cases. One patient complained of mild abdominal pain after SEMS insertion and another patient with inadequate drainage required insertion of a TDT for additional drainage. In SEMS insertion, the technical success (defined as correct placement) and clinical success (defined as resolution of occlusive symptoms) rates were 98.7% and 97.4%, respectively.

We attempted endoscopic decompression whenever possible, and decompression modality was chosen after discussion between the surgeon and endoscopist. Our institute introduced SEMS in 2013, and we have seen a moderate shift from TDT to SEMS since then. For lower rectal cancer, we prefer using TDT to avoid distal migration of the SEMS and interference with the transaction of the distal rectum. We did not insert SEMSs around the ileocecal valve due to technical difficulty and safety concerns. There were six such cases in the present series.

Among 75 SEMS cases, 57 cases were deemed eligible for inclusion in the present study, as all preoperative data necessary for calculating the CONUT score were available. The median interval between blood sampling and surgery was 1 day (range, 1–19 days). The characteristics of the 57 patients are summarized in Table 1. There were 34 men and 23 women. The mean age of the patients was 72.2 years (range, 37–90 years), and the median follow-up time was 26 months (range, 1–83). The CROSS classifications of the patients were as follows: CROSS 0, 33 patients (57.9%); CROSS 1, 7 patients (12.3%); CROSS 2, 6 patients (10.5%); and CROSS 3, 11 patients (19.3%). The mean interval between SEMS insertion and surgery was 17.7 days (range, 5–46 days), and the mean postoperative hospital stay was 19.5 days (range, 8–77 days). Some patients were only allowed a liquid diet after SEMS placement at the discretion of the physician, and 38 patients (66.7%) could resume a normal diet after drainage. Patients were received parenteral nutrition to meet their nutritional requirements when needed.

Fifty patients (87.7%) underwent curative resection with primary anastomosis. A stoma was created in seven patients, including two diverting stomas. Laparoscopic surgery was performed in 19 cases and conversion to an open procedure was reported in two cases because of the severe adhesion in one case and a tumor with direct invasion to the bladder in the other. There were three major postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ 3), including one in-hospital death secondary to anastomotic leakage. Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered for 25 cases (44%). The reasons for not administering chemotherapy were advanced age in 16 cases (50%) followed by patients' preference in seven cases (22%).

The mean CONUT score was 4.4 in the study. An ROC curve analysis revealed that the optimal cut-off value for the CONUT score was 7, which provided 82% sensitivity, 67% specificity, and an AUROC of 0.66 (Fig. 2).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated that CSS and DFS were significantly shorter in the CONUT score ≥ 7 group (p = 0.004, and p < 0.0001, respectively; Fig. 3). The relationship between the CONUT score status and the clinicopathological parameters of the 57 patients is shown in Table 2. A CONUT score of ≥ 7 was significantly associated with elevated CA19-9 levels (p = 0.03). Other clinicopathological factors and the interval between SEMS insertion and surgery were comparable between the groups. The postoperative complications and patterns of recurrence did not differ to a statistically significant extent according to the CONUT score.

Regarding CSS, univariate analyses revealed that the CONUT score (p = 0.005) was a significant prognostic factor. In the multivariate analysis, < 12 harvested lymph nodes (p = 0.08 in univariate analysis), and potential confounding variables, including T stage, N stage, venous invasion, and lymphatic invasion, were included in the model. The result showed that a CONUT score of ≥ 7 (hazard ratio [HR] = 10.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21–85.88, p = 0.03) was an independently associated with a poor prognosis (Table 3).

Regarding DFS, CONUT scores of ≥ 7 (p = 0.0002), and CA 19–9 ≥ 37 (p = 0.045) were identified as significant prognostic factors in univariate analyses. A multivariate analysis controlled for potential confounding variables demonstrated that CONUT score ≥ 7 (HR = 7.07, 95% CI 2.31–21.65, p = 0.0006) was independently associated with a poor prognosis (Table 4).

Discussion

The CONUT score was originally developed as a tool for nutritional assessment, and previous studies demonstrated its significant prognostic value in various malignancies [4,5,6,7,8]. The CONUT score is determined based on the serum albumin level, total cholesterol level, and total lymphocyte count. Albumin reflects the nutritional status and is also a non-specific marker of inflammation, chronic disease, and the fluid status [24]. Hypoalbuminemia was reported to be associated with cancer survival [1]. Cholesterol is a vital component of the cell membrane and is also associated with various signaling pathways [25]. The cholesterol level was reported to be correlated with tumor progression and cancer survival [26]. Lymphocytes have an anti-tumor effect, and a low lymphocyte count was reported to be associated with preexisting immunosuppression, as well as poor long-term cancer survival [27]. The CONUT score was reported to be significantly associated with the prognosis of patients with lung [4], pancreatobiliary [5], esophageal [6], gastric [7], and colorectal cancer [8, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. In the present study, we investigated the relationship between the CONUT score and the long-term outcomes of OCRC patients who underwent SEMS placement and received curative surgery, demonstrating that the preoperative CONUT score was an independent prognostic factor for CSS, and DFS.

Yang et al. [14] investigated the relationship between the CONUT score and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in colorectal cancer patients, and showed that the number and the positive rate of CTCs were significantly correlated with the CONUT score. A high CONUT score represents poor nutrition and an impaired anti-tumor immune status, which is an optimal environment for tumor growth, resulting in the increased release and survival of CTC. While there is still much to be investigated, the result revealed a potential mechanism underlying the association between a high CONUT score and poor long-term survival. Since the CONUT score is easily calculated from routinely measured laboratory results and has strong prognostic value, it should be easy and meaningful to incorporate into daily practice.

SEMS mechanically dilates OCRC, which raises concerns about short-term complications and long-term survival. SEMS placement was shown to increase the viable CTC count [28], cytokeratin 20 mRNA level [29], cell-free DNA level, and circulating tumor DNA levels in the peripheral blood [30]. SEMS placement was also associated with perineural invasion [31, 32]. However, these worrisome findings did not seem to directly translate to a poor prognosis, and recent meta-analyses revealed that the long-term outcomes of SEMS were comparable to those of emergency surgery when used as a BTS [10, 33], and as palliative therapy [34]. Moreover, the incidence rates of local and distant recurrence were not significantly different [10, 33]. In comparison to patients treated with a TDT, no statistically significant differences were observed with regard to patterns of recurrence and long-term survival [35].

Obstruction is considered a poor prognostic feature for which adjuvant chemotherapy is indicated [36]. However, adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to less than half of the patients in this study, mainly due to advanced age and patient preference. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not strongly recommended for stage II CRC by the Japanese guideline until 2019 [37], which might also have affected the decision. Although adjuvant chemotherapy was not associated with long-term outcomes in the present study, this result has to be interpreted with caution. We previously identified adjuvant chemotherapy as an independent prognostic factor in an extended cohort of 72 OCRC patients [38]. As the CONUT ≥ 7 was associated with a dismal prognosis, these patients might still be good candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy and close follow-up for such patients might be warranted.

There is heterogeneity in the reported thresholds used to define an elevated CONUT score in the literature. Previous studies used various cut-off values ranging from 2 to 5 [8]; the cut-off value of 7 in the present study seemed to be the largest value. Yoshimatsu et al. demonstrated that OCRC was associated with an increased CONUT score among 351 colorectal cancer patients [15]. The elevated CONUT scores might suggest that OCRC patients tended to be malnourished and inflamed in comparison to non-obstructive patients.

In the previous studies of colorectal cancer patients, the CONUT score was associated with age, postoperative complications, T Stage, tumor size, location, histologic grade, and distant metastasis [16,17,18]. In the present study, the CONUT score only showed a significant association with CA 19–9, and not with other clinicopathological parameters, postoperative complications, or postoperative hospital stay. This might be due to the small number of cases, and the different patient backgrounds in this study.

Several inflammation-based markers are calculated from the routinely measured laboratory results. They are considered to reflect the systemic inflammatory response and nutritional status of the host, and are significantly associated with the short- and long-term outcomes of various malignancies [39]. We previously reported the prognostic value of the prognostic nutritional index (PNI), neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte–monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet–lymphocyte ratio (PLR) [38], and modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) [40] using cohorts that overlapped with the current cohort, and demonstrated that the PNI was significantly associated with CSS (HR = 11.06, 95% CI 2.02–60.74, p = 0.006) and DFS (HR = 2.98, 95% CI 1.14–7.75, p = 0.026) [38]. The cohort in the present study was relatively small, which limited its statistical power; however, the present results indicated that the CONUT score was a stronger predictor of CSS and DFS than the PNI. Moreover, the results indicated that evaluating the immuno-nutritional status of the host, as represented by the CONUT score and PNI, was important for patient assessment and management.

In the present study, 18 eligible patients were excluded from the analysis due to a missing preoperative total cholesterol value, which was one of the limitations of the present study. Although the total cholesterol value itself has prognostic value [26], it was not recognized as an essential item in routine preoperative evaluations. Other limitations worth noting include the small sample size, the retrospective, non-randomized design, and the fact that it was performed in a single institution. The median follow-up period of 26 months was too short to draw definitive conclusions regarding oncological outcomes. The patients were OCRC cases who underwent SEMS placement and received curative surgery. They were a unique subset of colorectal cancer patients; thus, the results have to be interpreted with caution.

In summary, the results of the present study demonstrated that the preoperative CONUT score was an independent prognostic factor for CSS and DFS in OCRC patients who underwent SEMS placement as a BTS. Evaluating the immuno-nutritional status of the host by calculating the CONUT score complementarily strengthens the clinicopathological evaluation of the tumor, which might result in a more holistic assessment and tailored treatment. Future research with a large study population and a longer observation period is warranted.

References

Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J. 2010;9:69.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74.

Ignacio de Ulíbarri J, González-Madroño A, de Villar NG, González P, González B, Mancha A, et al. CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. 2005;20:38–45.

Shoji F, Haratake N, Akamine T, Shinkichi T, Masakazu K, Kazuki T, et al. The preoperative controlling nutritional status score predicts survival after curative surgery in patients with pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:741–7.

Kosei T, Piotr D, Wojciech GP, Stefan B, Jan NMI. The controlling nutritional status score and postoperative complication risk in gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatobiliary surgical oncology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab. 2019;74:303–12.

Yoshida N, Baba Y, Shigaki H, Kazuto H, Masaaki I, Junji K, et al. Preoperative nutritional assessment by controlling nutritional status (CONUT) is useful to estimate postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Surg. 2016;40:1910–7.

Takagi K, Domagala P, Polak WG, Buettner S, Wijnhoven BPL, Ijzermans JNM. Prognostic significance of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19:129.

Kosei T, Stefan B, Jan NMI. Prognostic significance of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020;78:91–6.

McCullough JA, Engledow AH. Treatment options in obstructed left-sided colonic cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2010;22:764–70.

Matsuda A, Miyashita M, Matsumoto S, Matsutani T, Sakurazawa N, Takahashi G, et al. Comparison of long-term outcomes of colonic stent as "bridge to surgery" and emergency surgery for malignant large-bowel obstruction: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:497–504.

Arezzo A, Passera R, Lo Secco G, Verra M, Bonino MA, Targarona E, et al. Stent as bridge to surgery for left-sided malignant colonic obstruction reduces adverse events and stoma rate compared with emergency surgery: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:416–26.

Allievi N, Ceresoli M, Fugazzola P, Montori G, Coccolini F, Ansaloni L. Endoscopic stenting as bridge to surgery versus emergency resection for left-sided malignant colorectal obstruction: an updated meta-analysis. Int J Surg Oncol. 2017;2017:2863272.

Dohomoto M. New method-endoscopic implantation of rectal stent in palliative treatment of malignant stenosis. Endosc Dig. 1991;3:1507–12.

Yang C, Wei C, Wang S, Han S, Shi D, Zhang C, et al. Combined features based on preoperative controlling nutritional status score and circulating tumour cell status predict prognosis for colorectal cancer patients treated with curative resection. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:1325–35.

Yoshimatsu K, Sagawa M, Yokomizo H, Yano Y, Okayama S, Satake M, et al. Clinical significance of controlling nutritional status (CONUT) in patients with colorectal cancer (in Japanese with English abstract). Japan J Surg Metab Nutri. 2017;51:183–90.

Yamamoto M, Saito H, Uejima C, Tanio A, Tada Y, Matsunaga T, et al. Prognostic value of combined tumor marker and controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score in colorectal cancer patients. Yonago Acta Med. 2019;62:124–30.

Tokunaga R, Sakamoto Y, Nakagawa S, Ohuchi M, Izumi D, Kosumi K, et al. CONUT: a novel independent predictive score for colorectal cancer patients undergoing potentially curative resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:99–106.

Iseki Y, Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Ohtani H, Sugano K, et al. Impact of the preoperative controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score on the survival after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132488.

Daitoku N, Miyamoto Y, Tokunaga R, Sakamoto Y, Hiyoshi Y, Iwatsuki M, et al. Controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score is a prognostic marker in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving first-line chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:4883–8.

Matsuzawa T, Ishida H, Yoshida S, Isayama H, Kuwai T, Maetani I, et al. A Japanese prospective multicenter study of self-expandable metal stent placement for malignant colorectal obstruction: short-term safety and efficacy within 7 days of stent procedure in 513 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:697–707.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13.

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–8.

Ballmer PE. Causes and mechanisms of hypoalbuminaemia. Clin Nutr. 2001;20:271–3.

Wang C, Li P, Xuan J, Zhu C, Liu J, Shan L, et al. Cholesterol enhances colorectal cancer progression via ROS elevation and MAPK Signaling Pathway Activation. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:729–42.

Zhou P, Li B, Liu B, Chen T, Xiao J. Prognostic role of serum total cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;477:94–104.

Iseki Y, Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Tamura T, Ohira G, et al. The impact of the preoperative peripheral lymphocyte count and lymphocyte percentage in patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 2017;47:743–54.

Yamashita S, Tanemura M, Sawada G, Moon J, Shimizu Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Impact of endoscopic stent insertion on detection of viable circulating tumor cells from obstructive colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:400–6.

Maruthachalam K, Lash GE, Shenton BK, Horgan AF. Tumour cell dissemination following endoscopic stent insertion. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1151–4.

Takahashi G, Yamada T, Iwai T, Takeda K, Koizumi M, Shinji S, et al. Oncological assessment of stent placement for obstructive colorectal cancer from circulating cell-free DNA and circulating tumor DNA dynamics. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:737–44.

Haraguchi N, Ikeda M, Miyake M, Yamada T, Sakakibara Y, Mita E, et al. Colonic stenting as a bridge to surgery for obstructive colorectal cancer: advantages and disadvantages. Surg Today. 2016;46:1310–7.

Kim HJ, Choi GS, Park JS, Park SY, Jun SH. Higher rate of perineural invasion in stent-laparoscopic approach in comparison to emergent open resection for obstructing left-sided colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:407–14.

Amelung FJ, Burghgraef TA, Tanis PJ, van Hooft JE, Ter Borg F, Siersema PD, et al. Critical appraisal of oncological safety of stent as bridge to surgery in left-sided obstructing colon cancer; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;131:66–75.

Ribeiro IB, Bernardo WM, Martins BDC, de Moura DTH, Baba ER, Josino IR, et al. Colonic stent versus emergency surgery as treatment of malignant colonic obstruction in the palliative setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E558–E56767.

Sato R, Oikawa M, Kakita T, Okada T, Oyama A, Abe T, et al. Comparison of the long-term outcomes of the self-expandable metallic stent and transanal decompression tube for obstructive colorectal cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:209–16.

National comprehensive cancer network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology, colon cancer, Version 1.2020. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, Tanaka S, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, et al. Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2014 for treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20:207–39.

Sato R, Oikawa M, Kakita T, Okada T, Oyama A, Abe T, et al. The prognostic value of the prognostic nutritional index and inflammation-based markers in obstructive colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 2020 Apr 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02007-5.

Dolan RD, Lim J, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with operable cancer: systematic review and metaanalysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16717.

Sato R, Oikawa M, Kakita T, Okada T, Abe T, Yazawa T, et al. Preoperative change of modified Glasgow prognostic score after stenting predicts the long-term outcomes of obstructive colorectal cancer. Surg Today. 2020;50:232–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in association with the present study.

Ethical statements

The protocol for this research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (#2019-0008) and conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sato, R., Oikawa, M., Kakita, T. et al. The Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) Score as a prognostic factor for obstructive colorectal cancer patients received stenting as a bridge to curative surgery. Surg Today 51, 144–152 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02066-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-020-02066-8