Abstract

Purpose

Music therapy has shown benefits for reducing distress in individuals with cancer. We explore the effects of music therapy on self-reported symptoms of patients receiving inpatient care at a comprehensive cancer center.

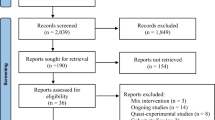

Methods

Music therapy was available as part of an inpatient integrative oncology consultation service; we examined interventions and symptoms for consecutive patients treated by a board-certified music therapist from September 2016 to May 2017. Patients completed the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS, 10 symptoms, scale 0–10, 10 most severe) before and after the intervention. Data was summarized by descriptive statistics. Changes in ESAS symptom and subscale scores (physical distress (PHS), psychological distress (PSS), and global distress (GDS)) were evaluated by Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

Data were evaluable for 96 of 100 consecutive initial, unique patient encounters; 55% were women, average age 50, and majority with hematologic malignancies (47%). Reasons for music therapy referral included anxiety/stress (67%), adjustment disorder/coping (28%), and mood elevation/depression (17%). The highest (worst) symptoms at baseline were sleep disturbance (5.7) and well-being (5.5). We observed statistically and clinically significant improvement (means) for anxiety (− 2.3 ± 1.5), drowsiness (− 2.1 ± 2.2), depression (− 2.1 ± 1.9), nausea (− 2.0 ± 2.4), fatigue (− 1.9 ± 1.5), pain (− 1.8 ± 1.4), shortness of breath (− 1.4 ± 2.2), appetite (− 1.1 ± 1.7), and for all ESAS subscales (all ps < 0.02). The highest clinical response rates were observed for anxiety (92%), depression (91%), and pain (89%).

Conclusions

A single, in-person, tailored music therapy intervention as part of an integrative oncology inpatient consultation service contributed to the significant improvement in global, physical, and psychosocial distress. A randomized controlled trial is justified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer patients undergoing active treatment experience a variety of symptoms throughout the illness trajectory that can have negative effects on their quality of life. These patients are faced with not only the physical side effects from the disease and its treatment, but also the psychological burden, which includes anxiety and stress [1]. In a review of symptom prevalence in oncology patients, the most commonly experienced symptoms included fatigue (62%), worrying (54%), feeling nervous (45%), dry mouth (42%), insomnia (41%), and feeling sad/mood (39%), with 40% of patients experiencing at least one symptom [2]. In addition to addressing physical needs of individuals with cancer, it is important to screen for psychological distress and provide interventions that can provide needed support [3, 4].

There is increased interest in the use of complementary health approaches to provide support for cancer patient physical and psychosocial needs. Complementary and integrative medicine (CIM) approaches include such interventions as music therapy, massage therapy, acupuncture, and meditation, which are being used together with conventional cancer care. In a survey of cancer patients, 54% reported initiation of at least one CIM approach after diagnosis [5]. In a 2016 systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers, 82.2% of websites offered information on a CIM approach such as music therapy, with 48.9% providing this therapy on-site [6]. These physical and psychosocial interventions have been found to increase quality of life and may contribute to improvements in treatment outcomes [7].

According to the American Music Therapy Association, music therapy “is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship … to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals.” [8] Music therapy can be utilized to alleviate and reduce psychological and physical symptoms of oncology patients [9,10,11]. Music therapy has been found to improve quality of life, decrease pain perception, promote self-expression, and provide spiritual support [12,13,14,15]. In an analysis exploring the effects of music therapy sessions on inpatients (93% with a cancer diagnosis) at a large academic hospital, music therapy improved pain, anxiety, depression, shortness of breath, mood, facial expression, and vocalization [16]. Common goals targeted by music therapists working in palliative and cancer care settings include (but are not limited to) supportive breathing, improving mood, and engaging in reminiscence [17].

At the University of Texas, MD Anderson Cancer Center, music therapy has been available to patients and caregivers through the Integrative Medicine Center in both inpatient and outpatient settings as part of an individual consultation or group programs. Additional integrative oncology clinical services provided through this center include physician consultations, oncology massage, acupuncture, physical therapy, nutrition counseling, meditation counseling, and health psychology [18]. For a patient to have an individual music therapy consultation in either the inpatient or outpatient setting, patients must first be referred to and evaluated by an integrative oncology physician and/or advanced practice provider, after which a decision is made regarding additional referrals to interventions such as music therapy, oncology massage, acupuncture, and/or health psychology.

Although we have learned about the physical and psychosocial benefits of music therapy for individuals with cancer, less is known about the real-world effects of music therapy on patient-reported outcomes. Real-world refers to learning more about an intervention such as music therapy as part of routine clinical practice, not as part of a formal clinical trial. This real-world study not only examines the effects of a single music therapy treatment on self-reported symptoms in patients receiving inpatient care at a comprehensive cancer center, it also explores reasons for referral to inpatient music therapy and associations between treatment goals and interventions.

Methods

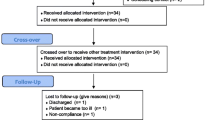

Participants

In this retrospective study, we analyzed baseline characteristics and patient-reported outcomes of the baseline encounter for 100 consecutive unique patients participating in a music therapy intervention as part of an integrative oncology inpatient consultation between September 1, 2016, and May 12, 2017. An integrative oncology physician and advanced practice provider performed an initial assessment, at which time the decision was made regarding an integrative care plan which could include referrals to additional integrative oncology services available on the inpatient units including music therapy, oncology massage, acupuncture, and/or health psychology.

Measures

As part of the initial music therapy evaluation, patients were asked by the music therapist to complete a patient-reported outcome assessment on paper before and after the intervention, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) [19]. The ESAS includes ten core symptoms (pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, appetite, well-being, shortness of breath, and sleep), on a numeric scale of 0 to 10 (10 = worst possible). ESAS subscale scores included global distress (GDS, 0–90), physical distress (PHS, 0–60), and psychological distress (PSS, 0–20). The GDS is the sum of pain, fatigue, nausea, drowsiness, appetite, shortness of breath, anxiety, depression, and well-being scores. The PHS is the sum of pain, fatigue, nausea, drowsiness, appetite, and shortness of breath. The PSS is the sum of anxiety and depression. Clinically significant change is described as a reduction ≥ 1 on an individual symptom score for the ESAS subscales. Additionally, reduction of GDS ≥ 3, PHS ≥ 2, and PSS ≥ 2 indicates clinically significant change [20, 21].

Data extracted from the medical record included demographics, cancer diagnosis, and reasons for referral as documented by the referring integrative oncology physician and/or advanced practice provider. Additionally, patient descriptors (affect, attention, participation, mood), session time, session goals, and interventions as documented by the music therapist were also extracted. Inpatient music therapy data was collected in a database as part of an IRB-approved protocol. We analyzed data from consecutive consultations.

Music therapy interventions

As part of a real-world study, the music therapy session did not follow a specific protocol—interventions were tailored to patient needs based on the best clinical judgment of a board-certified music therapist with greater than 5 years of experience. Session goals were determined by the music therapist as part of the therapeutic relationship, supported by patient responses to a patient-reported outcome assessment; each session may have had one or more goals (e.g., distraction, reduce anxiety, promote relaxation, improve coping skills, promote self-expression, improve quality of life, pain management, and/or mood elevation). One or more interventions may have been used as part of a session to help achieve these goals. Types of interventions included the following: Active music making/active music engagement (AME) requires active participation from the patient (i.e., playing the drum). ISO-principle is a concept of matching various aspects of music with an equal behavior or mood of an individual [22]. Lyric analysis and songwriting involves using existing songs and lyrics to facilitate meaningful discussion and/or creating one’s own lyrics and music. Therapeutic singing and oral motor and respiratory exercises (OMREX) are neurologic music therapy (NMT) techniques; the music therapist had NMT training. Therapeutic singing “involves the unspecified use of singing activities to facilitate initiation, development, and articulation in speech and language as well as to increase functions of respiratory apparatus” [23]. OMREX involves “the use of musical materials and exercises, mainly through sound vocalization and wind instrument playing, to enhance articulatory control and respiratory strength and function of the speech apparatus” [24]. Music listening is a passive form of intervention where an individual is listening to live or recorded music.

Data analysis

Data analyzed included demographics, cancer diagnosis, reason for referral, music therapy goals, music therapy intervention, and symptom scores (ESAS) before and after the session. Data was summarized by descriptive statistics including mean and standard deviation, median and range for continuous variables, and frequency and proportion for categorical variables. Change in ESAS symptom score and subscales for those who had a symptom score of greater than or equal to 1 at baseline is evaluated by Wilcoxon signed rank test. ESAS subscales included in the analysis were only for those patients who had a score of one or more in at least one ESAS symptom in the respective subscale. The clinical response rate was defined as a reduction of ≥ 1 in symptom scores, ≥ 3 in GDS subscale, and ≥ 2 in PHS and PSS subscales. The association between music therapy goals and interventions was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test.

Results

For the period September 2016 through May 2017, we collected data on 100 consecutive unique patients evaluated by a music therapist as part of an integrative medicine inpatient consultation service; data were evaluable for 96/100 unique patients. The patients’ mean age was 50.4, with the majority women (55.2%), and of white race (71.7%). The most common cancer diagnoses included leukemia (33.3%) followed by myeloma/lymphoma (13.5%) and thoracic/head and neck (13.5%). The mean time for a music therapy session was 36.9 min, with maximum of 65 min. As assessed by the music therapist, the majority of participants had congruent affect (62.1%), an intense/sustained level of attention (82.1%), with a high level of participation (78.9%) and euthymic mood (64.5%) (see Table 1 for patient characteristics).

Summarized in Table 2 are the reasons for music therapy referral, session goals, and interventions. The most common reasons for referral to music therapy as documented by the integrative oncology physician and/or advanced practice provider include anxiety stress (66.7%), adjustment disorder/coping (28.1%), mood elevation/depression (20.8%), and relaxation (12.5%). The most common session goals as documented by the music therapist include distraction (56.3%), reducing anxiety (41.7%), promoting relaxation (41.7%), and improving coping skills (24.0%). Of six intervention categories, the majority of interventions included music listening (70.8%) and use of the ISO-principle (25.0%).

The highest/worst baseline individual symptom scores were for sleep (5.7), well-being (5.5), fatigue (5.4), and anxiety (5.2). Table 3 shows the statistical test results. Statistically and clinically significant pre-post session ESAS symptom score change was observed for all individual ESAS symptom except for poor sleep and poor well-being. The highest clinical response rates were observed for individual symptoms of anxiety (91.7%), depression (90.6%), pain (88.9%), and fatigue (88.6%). For all three ESAS subscales, we observed statistically and clinically significant change.

For our 96 evaluable patients, we explored the association between music therapist goals and interventions selected as part of the music therapy session. Only three session goals had a significant association with the selected intervention: anxiety, distraction, and relaxation. Patients with goal of anxiety reduction were significantly less likely to receive AME as part of their treatment plan (p = 0.03), with only 7.5% receiving AME. Patients with goal of relaxation were significantly less likely to have received the ISO-principle, AME, or lyric analysis or songwriting as part of their treatment plan (p < 0.05). Patients with goal of distraction were significantly more likely to receive music listening as an intervention (p = 0.01). Music listening was also the most common intervention for patients with goal of distraction (81.5%), anxiety reduction (80%), and relaxation (75%).

Discussion

Our retrospective study provides insight into the real-world effects of music therapy on cancer patients receiving inpatient care at a comprehensive cancer center. Findings from real-world analyses can help inform clinical practice as well as the design of future randomized trials. In this consecutive sample of patients, we observed clinically significant improvement across a variety of symptoms commonly experienced by cancer patients, after one session of music therapy. The overall symptom burden was in the moderate range, with symptom scores between 4 and 6. Although the majority of referrals were for management of mood symptoms (anxiety/stress, adjustment disorder/coping, mood elevation/depression), we observed statistically and clinically significant improvements in both physical (ESAS PHS) and psychosocial symptoms (ESAS PSS) when assessed immediately before and after the music therapy session. Prior literature has demonstrated clinically meaningful effects of music therapy on both physical and psychosocial symptoms [9, 10].

We also observed that the majority of interventions included music listening, rather than more physically active interventions such as music making. Active music making interventions were less likely in patients with goals of anxiety reduction and relaxation, while music listening, a more passive intervention, was more common for anxiety reduction and relaxation. This observation may be the result of the music therapist selecting less active interventions when working with a more physically limited inpatient population with high levels of distress. Active music making interventions such as singing or instrument playing may be more desirable in an outpatient population with lower symptom burden. Although music listening is a more passive intervention for the patient, the process of music selection and playing by the therapist is an active process, based on clinical judgment, different than having a patient listen to pre-recorded music.

Of note, close to half of patients referred to music therapy in the inpatient setting had a diagnosis of a hematologic malignancy. When considering safety of integrative interventions, music therapy presents a low to minimal risk for patients with thrombocytopenia and/or neutropenia. Severe cytopenias would make patients less ideal candidates for more invasive integrative treatments such as acupuncture or massage.

A strength of this real-world study is that the music therapist developed a personalized treatment plan to address individual patient symptom needs; there was no protocol limiting which interventions could be used during the session. Another notable strength, symptom score change was assessed immediately before and after the music therapy session. Immediate pre/post-assessment can help reduce the effects of other events or interventions taking place during the inpatient admission on self-reported symptoms.

Limitations of this study include that it is an analysis of observational data using a convenience sample without a control group. It is possible that decreases in scores were related to receiving caring attention, rather than the music therapy intervention specifically. Having the ESAS administered by the music therapist introduces a potential bias of social desirability, where the patient desires to please the music therapist. Our results are limited to the immediate pre-post effects of a single clinical encounter, which does not allow us to measure the durability of these effects. Also, this sample represents patients seen in an inpatient setting at a comprehensive cancer center, which may not be representative of the population of patients with access to music therapy in an outpatient or community setting.

With initiatives in place to explore the role of non-pharmacologic strategies to help with symptom relief [24], there is a need to identify which types of interventions can provide clinically meaningful benefits for patients. Using an evidence-informed approach, integrative medicine interventions such as music therapy have the potential to improve symptom control. Our real-world analysis provides insight into the immediate, clinically meaningful benefits of a single music therapy session on self-reported symptoms in an acute, oncology care setting. A randomized controlled trial could include the use of an attention control group, controlling for non-specific effects of the encounter such as therapeutic presence, or use of an alternative treatment method like relaxation training with a health psychologist. It would be valuable to examine if certain types of patients respond more strongly to music therapy than others, such as individuals who specifically chose music therapy or those who believe music is part of his/her self-identity. Future research should explore the effects of session frequency, and length and content on symptom change, especially how to more effectively use self-reported outcomes in tailoring music therapy interventions.

References

Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Dueck AC et al (2014) Recommended patient-reported core set of symptoms to measure in adult cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 106(7). https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju129

Kim EJE, Dodd MJ, Aouizerat BE et al (2009) A review of the prevalence and impact of multiple symptoms in oncology patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 37(4):715–736

De Haes JCJM, Van Knippenberg FCE, Neijt JP (1990) Measuring psychological and physical distress in cancer patients: structure and application of the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist. Br J Cancer 62:1034–1038

Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B et al (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer cite. Psycho-Oncology. 10:19–28

Vapiwala N, Mick R, Hampshire MK, Metz JM, DeNittis AS (2006) Patient initiation of complementary and alternative medical therapies (CAM) following cancer diagnosis. Cancer J 12(6):467–474

Yun H, Sun L, Mao JJ (2017) Growth of integrative medicine at leading cancer centers between 2009 and 2016: a systematic analysis of NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center websites. JNCI Monographs 2017(52):29–32

Sparber A, Bauer L, Curt G et al (2000) Use of complementary medicine by adult patients participating in cancer clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum 27(4):623–630

American Music Therapy Association. What is music therapy? https://www.musictherapy.org/about/musictherapy/ [Accessed January 28, 2019]

Bradt J, Dileo C, Magill L et al (2016) Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD006911

Zhang JM, Wang P, Yao JX, Zhao L, Davis MP, Walsh D, Yue GH (2012) Music interventions for psychological and physical outcomes in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Cancer Care 20:3043–3053

Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L (2013) Music-based interventions in palliative cancer care: a review of quantitative studies and neurobiological literature. Support Care Cancer 21(9):2609–2624

Stanczyk MM (2011) Music therapy in supportive cancer care. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 16:170–172

Yates GJ, Silverman MJ (2015) Immediate effects of single-session music therapy on affective state in patients on a post-surgical oncology unit: a randomized effectiveness study. Arts Psychother 44:57–61

Lee JH (2016) The effects of music on pain: a meta-analysis. J Music Ther 53(4):430–477

Wlodarczyk N (2007) The effect of music therapy on the spirituality of persons in an in-patient hospice unit as measured by self-report. J Music Ther 44(2):113–122

Gallagher LM, Lagman R, Rybicki L (2018) Outcomes of music therapy interventions on symptom management in palliative medicine patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35(2):250–257

Clements-Cortes A (2017) Singing and vocal interventions in palliative and cancer care: music therapists’ perceptions of usage. J Music Ther 54(3):336–361

Lopez G, McQuade J, Cohen L, Williams JT, Spelman AR, Fellman B, Li Y, Bruera E, Lee RT (2017) Integrative oncology physician consultations at a comprehensive cancer center: analysis of demographic, clinical and patient reported outcomes. J Cancer 8(3):395–402

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K (1991) The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 7(2):6–9

Hui D, Shamieh O, Eduardo PC et al (2015) Minimal clinically important differences in the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale in cancer patients: a prospective, multicenter study. Cancer. 121(17):3027–3035

Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE et al (2016) Minimally clinically important difference in physical, emotional, and total symptom distress scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manag 1(2):262–269

Heiderscheit A, Madson A (2015) Use of the ISO-principle as a central method in mood management: a music psychotherapy clinical case study. Music Ther Perspect 33(1):45–52

Thaut MH (2005) Rhythm, music and the brain: scientific foundations and clinical applications, studies on new music research, vol 7. Taylor and Francis, New York ISBN 0415973708

Tick H, Nielsen A, Pelletier KR et al (2018) Evidence-based non-pharmacologic strategies for comprehensive pain care: the Consortium Pain Task Force White Paper. Explore (NY) 14(3):177–211

Acknowledgements

The contribution of music therapist, Antonio Milland Santiago, for delivery of the music therapy interventions is acknowledged.

Funding

This work was financially supported by a grant from the Duncan Family Institute for Cancer Prevention and Risk Assessment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lopez, G., Christie, A.J., Powers-James, C. et al. The effects of inpatient music therapy on self-reported symptoms at an academic cancer center: a preliminary report. Support Care Cancer 27, 4207–4212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04713-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04713-4