Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of chemotherapy, a geriatric assessment is recommended in elderly patients with cancer. We aimed to characterize and compare patients with aggressive lymphoma by objective response and survival status based on pre-treatment cancer-specific geriatric (C-SGA) and quality of life (QoL) assessments.

Methods

Patients not eligible for anthracycline-based first-line therapy or intensive salvage regimens completed C-SGA and QoL assessment before and after a rituximab-bendamustine-lenalidomide (R-BL) treatment in a phase II clinical trial. Clinical outcomes were compared based on pre-treatment individual and summary C-SGA measures, their cutoff-based subcategories and QoL indicators, using Wilcoxon rank sum or chi-square tests.

Results

A total of 57 patients (41 included in the clinical trial) completed a C-SGA. Participants with pre-treatment impaired functional status (Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 score ≥3) were more likely to experience worse outcomes: a higher proportion were non-responders, died before the median follow-up of 31.6 months (interquartile range (IQR) 27.9–37.9) or died during treatment. Non-responders were patients categorized as having possible depression (Geriatric Depression Scale-5 score ≥2) and with worse QoL scores for functional performance. Patients with worse C-SGA summary scores and with greater tiredness were more likely to die during treatment.

Conclusion

A pre-treatment impaired functional status is an important factor with respect to clinical outcomes in patients receiving an R-BL regimen. Individual geriatric and related QoL domains showed similar associations with clinical outcomes. Whether interventions targeting specific geriatric dimensions also translate in better symptom- or domain-specific QoL warrants further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in older patients [25]. Incidence rates are increasing especially in those >60 years of age [36]. Older patients with cancer are a heterogeneous population with regard to daily functioning, comorbidities, disabilities, and geriatric conditions [12, 16]. In 60 to 70% of NHL patients >60 years, comorbid conditions are common with the consequence that many of these patients are not eligible for randomized clinical trials [24]. Trials specifically designed for older cancer patients do often not address endpoints that are relevant for this population [48]. The impact of treatment on quality of life (QoL), functional capacities, cognition, and social situation may be more important than the prolongation of life. Older cancer patients tend to weight their QoL as more important than gain in survival compared to younger patients [31, 45]. Information on QoL in DLBCL patients are predominantly from studies on survivors at all ages [28, 43], which may not adequately reflect QoL in patients who have a poorer prognosis or are unfit to receive standard treatment.

A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) defined as a multi-dimensional diagnostic process to determine an older person’s medical, psychosocial, and functional capabilities is recommended to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of chemotherapy in older cancer patients [47]. There is growing evidence that several domains are associated with treatment toxicity, mortality, and treatment decision-making [33]. In studies with older or unfit patients with DLBCL, a CGA has been used to prospectively identify frail patients [23], patients who can benefit from a curative approach [41, 42] or to modify chemotherapy [29, 39].

In settings where so-called standard treatment therapy is not feasible, and the proportion of older patients is increasing, meaningful outcomes as represented by the different dimensions of a CGA and QoL should be mandatory [48]. We aimed to characterize and compare patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma receiving a rituximab, bendamustine, and lenalidomide (R-BL) regimen [17] by response and survival status based on pre-treatment cancer-specific geriatric (C-SGA) and QoL assessments. We also report on changes in C-SGA and QoL from pre- to post-treatment and characterize and compare patients registered vs. those not registered to the phase II trial based on C-SGA and QoL.

Methods

This was an open-label, prospective, multi-center phase II clinical trial designed to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of an R-BL regimen in patients not eligible for anthracycline-based first-line therapy or intensive salvage regimens. Patients with histologically confirmed aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma including DLBCL, transformed follicular lymphoma (FL), or FL grade 3b according to the WHO classification were enrolled in 12 Swiss centers from August 2011 to January 2014. Details on eligibility criteria are described elsewhere [17]. For response assessment, criteria of the International Working Group for evaluation of response in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma were used. Response was defined as complete response, unconfirmed complete response, or partial response (CR/CRu+PR) [8].

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee and institutional review board for each site, and patients provided separate written informed consent for C-SGA and QoL assessments [17]. The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00987493.

Assessments

All patients were required to undergo C-SGA and to complete a QoL form before treatment start, at day 1 of each cycle and within 1 month after completing treatment.

The C-SGA was developed by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK C-SGA) for specific use in clinical trials including older patients applying a mix of medical record abstraction and patient interview. Feasibility was confirmed in a cross-sectional study of cancer patients presenting for initiation of chemotherapy treatment [9]. The SAKK C-SGA consists of six standard geriatric assessment measures [16] covering the domains: comorbidity, functional status, psychosocial including depression and social support, nutrition, and cognition (Table 1). From these measures, six individual scores and one summary score is obtained (varying scales, range from 0–5 to 1–100). Continuous individual measure scores are dichotomized based on the individual measure’s established cutoff. The summary SAKK C-SGA score is calculated by summing the number of “deficit” scores in each of the 5 domains (range from 0 to 5) and dichotomizing deficits as ≤2 (low risk) vs. ≥3 (at risk) for poor outcomes using known cut points of deficits [10].

The QoL assessment included five global QoL domains related to the C-SGA domains for physical well-being, mood, coping effort, functional performance, and overall treatment burden [3, 6], and three indicators specific to side-effects (tiredness, nausea/vomiting, and taste disturbances) [11]. Physical well-being, mood, and functional performance represent the physical, emotional, and functional domain of most multi-dimensional cancer-related QoL measures. All QoL scales were measured by single-item visual analog scales ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicate a worse condition.

Analysis

Pre-treatment summary and individual C-SGA measures, their subcategories based on respective cutoffs, and QoL indicators were compared for the following clinical outcomes: response, survival status (dead or alive at the time of the analysis), time point of death (during vs. after treatment), and study participation. The Wilcoxon rank sum and chi-square tests were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Post- and pre-treatment C-SGA and QoL assessments were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous and McNemar’s or Bowker’s test of symmetry for categorical variables. The Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival is presented for the pre-treatment scores showing an impact on survival status. No adjustment was made for multiple testing due to the exploratory nature of this study.

Results

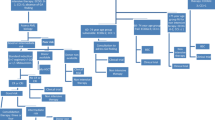

A total of 57 patients completed a pre-treatment C-SGA, among those 41 were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Patient and disease characteristics are shown in Table 2. Median age was 75 (min-max: 40–94) years with 83% of the patients being older than 65 years. A majority (80%) had a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score of more than 4 (80%), a performance status of 0 or 1 (85%), presented with advanced stage disease (63%) and had an international prognostic index (IPI) of low/low-intermediate risk status (54%). The median follow-up was 31.6 (IQR 27.9–37.9) months at the time point of trial termination. Older patients (≤75 vs. >75) had a higher CCI, and C-SGA summary score, and reported less nausea. Patients with a higher performance status (0 or 1 vs. ≥2) had higher Vulnerable Elders Survey-13 (VES-13) scores and C-SGA summary scores. Patients with an IPI of high or high-intermediate risk reported worse physical well-being than those with a low or low-intermediate risk (data not shown).

Table 3 displays the pre-treatment C-SGA and QoL scores by response. A higher proportion of patients who did not achieve CR/CRu+PR had an impaired functional status (VES-13 score ≥3; 63% vs. 24%, p = 0.014), possible depression (GDS-5 score ≥2; 38% vs. 8%, p = 0.020), and reported lower functional performance (median (min-max) = 33 (1–97) vs. 13 (2–99), p = 0.045). For all other C-SGA and QoL domains, no significant differences were found between the two response groups before treatment start.

Among the 25 patients who had a normal functional status at baseline, 14 completed all 6 cycles of therapy, while none out of 16 patients with impaired functional status completed all 6 cycles (Supplemental material Table S1). Six patients needed a dose reduction for bendamustine and 10 patients for lenalidomide, with similar proportion in patients with and without impaired functional status (data not shown).

Pre-treatment scores for C-SGA and QoL by survival status (Table 4) differed in functional status. A higher proportion of patients who had died had pre-treatment impaired functional status (53% vs. 0%, p = 0.003) compared to those who were still alive. The Kaplan-Meier curve of overall survival according to the pre-treatment scores for functional status is presented in Fig. 2.

A higher proportion of patients who died during treatment versus those who died during follow-up (Table S2 supplemental material) had pre-treatment impaired functional status (89 vs. 38%, p = 0.011), poor outcomes (C-SGA summary score; 78 vs. 33%, p = 0.025), and reported worse tiredness (median (min-max) = 90 (16–100) vs. 59 (2–92), p = 0.002).

Comparisons of pre-treatment C-SGA and QoL scores between patients who were registered and those who were not registered to the trial (Table S3 supplemental material) showed that in a greater proportion of registered patients, depression was unlikely (80 vs. 38%, p = 0.002). Registered patients also reported higher scores in the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) indicating a better nutritional status (median (min-max) = 10 (5–13) vs. 8.5 (3–12), p = 0.020; for total score), less taste disturbance (median (min-max) = 6 (0–90) vs. 24 (1–89), p = 0.012), and less anticipated treatment burden (median (min-max) = 10 (0–67) vs. 46 (0–94), p = 0.046).

Significant changes from pre- to post-treatment assessments were found for the function and nutrition domains (Fig. S1 supplemental material). The proportion of patients who had impaired functional status increased from 21 to 46% (p = 0.014). Scores for nutrition worsened (from median (min-max) = 11 (6–13) to 9 (5–12), p = 0.008). This is also reflected in the overall C-SGA score with a trend to a higher proportion of patients becoming at risk for a poor outcome after the end of treatment (p = 0.059). The effort to cope with the disease decreased from pre- to post-treatment (p = 0.042; Fig. S2 supplemental material).

Discussion

Pre-treatment geriatric assessment of older patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma is important to determine potential treatment tolerance and to restore or prevent health or QoL decline [24]. In our population of patients receiving a R-BL regimen, we found worse clinical outcomes for patients who had impaired functional status before treatment start. This geriatric domain was the only among five domains that was related to response, survival status, and time point of death. Non-responders were also patients categorized as having possible depression, and patients with worse C-SGA summary scores were more likely to die during treatment.

Our results are in line with several studies that identified loss of function in activities of daily living (ADL) to be a predictor of survival in older patients with DLBCL [27, 39, 49]. A larger study with a mixed cancer population including patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma reported also that poor mobility was a risk factor for early death [37]. Other studies in this population examined the response rate [29, 41] and survival [39, 42, 49] of patients categorized as frail, unfit, or fit rather than according to individual dimensions of the geriatric assessment. Tucci et al. [41] found response rate to be significantly higher in patients considered as “fit” compared with “unfit” patients. Similar to the study of Olivieri et al. [29], who found no significant difference in the response rate between patients considered as “fit”, “unfit”, or “frail”, we found that the characterization of patients “at risk” vs. “not at risk” for poor outcome was not significantly associated with response. In our sample, possible depression was associated with response but not with survival status. This is in contrast to a recent study showing that emotional disorders had a negative effect on overall survival in older patients with advanced ovarian cancer [40].

Patients not registered compared to those registered to the study had a higher risk for depression and malnutrition. Although we had fewer patients than anticipated in the group of patients not registered to the study with a pre-treatment C-SGA assessment available, psychological and nutritional state may be factors that influence the decision whether or not to include patients in the study. Limited information exists on the impact of a pre-treatment CGA on the cancer treatment plan [32]. Similar to our findings, Girre et al. [14] reported the absence of depressive symptoms and body mass index to be associated with a modification of the treatment plan, whereas Chaibi et al. [7] found that more frequent severe comorbidities and dependence for at least one ADL led to delay in or less intensive treatment in cancer patients older than 70 years.

Pre-treatment QoL indicators for functional performance and tiredness were significantly related to the clinical outcomes. Taste disturbance and treatment burden were associated with a patient’s registration to the study. The significant associations of specific individual QoL indicators and geriatric domains with the clinical outcomes show a similar pattern. Targeting specific geriatric dimensions may also translate in better symptom- or domain-specific QoL in a population of patients to whom QoL is more important than gains in survival [31, 45]. Studies in older cancer patients receiving chemotherapy showed that function and comorbidity were independent predictors of QoL [46] and that those patients identified as frail by a CGA had significantly worse global QoL [19]. A small pilot study found that a CGA with structured multi-disciplinary follow-up according to risk resulted in improved QoL scores in older breast cancer patients [13].

Changes in C-SGA domains and QoL indicators from pre- to post-treatment indicate a significant worsening in the overall C-SGA score probably driven by the significant worsening in functional and nutritional status post-treatment. Despite these deteriorations, patients reported less effort to cope with the disease over time. This may indicate an adaptation to the disease considering that the psychosocial and cognitive components of the geriatric assessment remained stable over the course of treatment. A comparison of our results with existing studies is difficult because changes in geriatric dimension over time have rarely been reported [32]. In older breast cancer patients, one study reported an increase from an average of six to nine geriatric problems over a 6-month follow-up period [13], while another study found that women maintained their baseline ability to perform ADLs after 6 months despite remarkable toxicity of the chemotherapy received [18]. No changes in functional but improvements in symptom-specific and global QoL have been reported in patients with DLBCL who were treated with progressive [22] or cautious treatment [22, 38].

A strength of our study is that we assessed all components of a C-SGA including not only daily functioning and comorbidities but also nutritional status, cognitive function, psychological state, and social support [24]. The concurrent assessment of C-SGA and QoL components allowed observation of parallels between these two constructs. Without the characterization of older patients included in clinical trials by CGA and QoL status, the extrapolation of study results to the general older cancer population is limited [48]. A further strength is the inclusion of a post-treatment C-SGA facilitating investigation of changes in individual C-SGA and QoL components over the course of treatment. This is rare in phase II trials in general and specifically, in patients with DLBCL [33].

Limitations include that the age of patients was not restricted to older patients as initially intended. The number of participants younger than 60 years (n = 5) was small, and the results of a sensitivity analysis excluding these patients were similar. The VES-13 is not a pure functional assessment tool such as ADL or any of the direct functional measures [30]. It includes the patient’s estimation of his or her own health, and the age of >85 years is considered a criterion for vulnerability by itself. However, the VES-13 covers only one dimension of a CGA. It is considered as useful and accurate when diagnosing impaired functional status [20, 21]. Changes over time were only reported for patients who completed the second assessment, which may have introduced a bias towards underestimating the impact of treatment on geriatric and QoL domains. Due to the small study sample, we cannot exclude that other than the reported domains may be associated with clinical outcomes. No specific tool for a CGA is recommended [24], and the number of geriatric domains and corresponding measures vary in clinical studies, which limits the comparison of our results with those of other studies.

Although some studies in other types of cancer have assessed both C-SGA and QoL [1, 4, 13, 18, 19, 33, 46], future research is needed to study geriatric and QoL dimensions concurrently and to investigate their interplay in order to obtain information how to tailor geriatric interventions to ultimately improve QoL of older patients. Prospective studies for older patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma incorporating a broader coverage of CGA domains are necessary.

In conclusion, our results suggest that pre-treatment impaired functional status based on the VES-13 cutoff is an important factor with respect to clinical outcomes in patients not eligible for anthracycline-based first-line therapy or intensive salvage regimens. Individual geriatric domains and related QoL indicators showed similar associations with clinical outcomes. Whether interventions targeting specific geriatric dimensions also translate in better symptom- or domain-specific QoL warrants further research.

References

Bailey C, Corner J, Addington-Hall J, Kumar D, Haviland J (2004) Older patients’ experiences of treatment for colorectal cancer: an analysis of functional status and service use. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 13:483–493

Bernhard J, Lowy A, Mathys N, Herrmann R, Hurny C (2004) Health related quality of life: a changing construct? Qual Life Res 13:1187–1197

Bernhard J, Maibach R, Thurlimann B, Sessa C, Aapro MS, Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer R (2002) Patients’ estimation of overall treatment burden: why not ask the obvious? J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 20:65–72

Biesma B, Wymenga AN, Vincent A, Dalesio O, Smit HJ, Stigt JA, Smit EF, van Felius CL, van Putten JW, Slaets JP, Groen HJ, Dutch Chest Physician Study G (2011) Quality of life, geriatric assessment and survival in elderly patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with carboplatin-gemcitabine or carboplatin-paclitaxel: NVALT-3 a phase III study. Ann Oncol 22:1520–1527

Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M (2003) The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:1451–1454

Butow P, Coates A, Dunn S, Bernhard J, Hurny C (1991) On the receiving end. IV: validation of quality of life indicators. Ann Oncol 2:597–603

Chaibi P, Magne N, Breton S, Chebib A, Watson S, Duron JJ, Hannoun L, Lefranc JP, Piette F, Menegaux F, Spano JP (2011) Influence of geriatric consultation with comprehensive geriatric assessment on final therapeutic decision in elderly cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 79:302–307

Cheson BD (2007) The International Harmonization Project for response criteria in lymphoma clinical trials. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 21:841–854

Clough-Gorr KM, Noti L, Brauchli P, Cathomas R, Fried MR, Roberts G, Stuck AE, Hitz F, Mey U (2013) The SAKK cancer-specific geriatric assessment (C-SGA): a pilot study of a brief tool for clinical decision-making in older cancer patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 13:93

Clough-Gorr KM, Thwin SS, Stuck AE, Silliman RA (2012) Examining five- and ten-year survival in older women with breast cancer using cancer-specific geriatric assessment. Eur J Cancer 48:805–812

Coates A, Glasziou P, McNeil D (1990) On the receiving end—III. Measurement of quality of life during cancer chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 1:213–217

Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, Mohile S, Wedding U, Basso U, Colloca G, Rostoft S, Overcash J, Wildiers H, Steer C, Kimmick G, Kanesvaran R, Luciani A, Terret C, Hurria A, Kenis C, Audisio R, Extermann M (2015) Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendations. Ann Oncol 26:288–300

Extermann M, Meyer J, McGinnis M, Crocker TT, Corcoran MB, Yoder J, Haley WE, Chen H, Boulware D, Balducci L (2004) A comprehensive geriatric intervention detects multiple problems in older breast cancer patients. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 49:69–75

Girre V, Falcou MC, Gisselbrecht M, Gridel G, Mosseri V, Bouleuc C, Poinsot R, Vedrine L, Ollivier L, Garabige V, Pierga JY, Dieras V, Mignot L (2008) Does a geriatric oncology consultation modify the cancer treatment plan for elderly patients? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 63:724–730

Hall WH, Ramachandran R, Narayan S, Jani AB, Vijayakumar S (2004) An electronic application for rapidly calculating Charlson comorbidity score. BMC Cancer 4:94

Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC (2012) Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 13:e437–e444

Hitz F, Zucca E, Pabst T, Fischer N, Cairoli A, Samaras P, Caspar CB, Mach N, Krasniqi F, Schmidt A, Rothermundt C, Enoiu M, Eckhardt K, Berardi Vilei S, Rondeau S, Mey U (2016) Rituximab, bendamustine and lenalidomide in patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma not eligible for anthracycline-based therapy or intensive salvage chemotherapy—SAKK 38/08. Br J Haematol 174(2):255–263

Hurria A, Hurria A, Zuckerman E, Panageas KS, Fornier M, D’Andrea G, Dang C, Moasser M, Robson M, Seidman A, Currie V, VanPoznak C, Theodoulou M, Lachs MS, Hudis C (2006) A prospective, longitudinal study of the functional status and quality of life of older patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Am Geriatr Soc 54:1119–1124

Kim YJ, Kim JH, Park MS, Lee KW, Kim KI, Bang SM, Lee JS, Kim CH (2011) Comprehensive geriatric assessment in Korean elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 137:839–847

Luciani A, Ascione G, Bertuzzi C, Marussi D, Codeca C, Di Maria G, Caldiera SE, Floriani I, Zonato S, Ferrari D, Foa P (2010) Detecting disabilities in older patients with cancer: comparison between comprehensive geriatric assessment and vulnerable elders survey-13. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 28:2046–2050

Luciani A, Foa P (2011) Reply to M.J. Molina-Garrido et al. J Clin Oncol 29:3202–3203

Merli F, Bertini M, Luminari S, Mozzana R, Berte R, Trottini M, Stelitano C, Botto B, Pizzuti M, Quintana G, De Paoli A, Federico M, Intergruppo Italiano L (2004) Quality of life assessment in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with anthracycline-containing regimens. Report of a prospective study by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Haematologica 89:973–978

Merli F, Luminari S, Rossi G, Mammi C, Marcheselli L, Tucci A, Ilariucci F, Chiappella A, Musso M, Di Rocco A, Stelitano C, Alvarez I, Baldini L, Mazza P, Salvi F, Arcari A, Fragasso A, Gobbi PG, Liberati AM, Federico M (2012) Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and rituximab versus epirubicin, cyclophosphamide, vinblastine, prednisone and rituximab for the initial treatment of elderly “fit” patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the ANZINTER3 trial of the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Leuk Lymphoma 53:581–588

Morrison VA, Hamlin P, Soubeyran P, Stauder R, Wadhwa P, Aapro M, Lichtman S (2015) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the elderly: impact of prognosis, comorbidities, geriatric assessment, and supportive care on clinical practice. An International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) expert position paper. J Geriatr Oncol 6:141–152

Morrison VA, Hamlin P, Soubeyran P, Stauder R, Wadhwa P, Aapro M, Lichtman SM (2015) Approach to therapy of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the elderly: the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) expert position commentary. Ann Oncol 26:1058–1068

Moser A, Stuck AE, Silliman RA, Ganz PA, Clough-Gorr KM (2012) The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. J Clin Epidemiol 65:1107–1116

Nabhan C, Smith SM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, Parsons B, Karmali R, Feliciano J, Hanson B, Smith S, McKoy J, Larsen A, Hantel A, Gregory S, Evens AM (2012) Analysis of very elderly (>/=80 years) non-Hodgkin lymphoma: impact of functional status and co-morbidities on outcome. Br J Haematol 156:196–204

Oerlemans S, Issa DE, van den Broek EC, Nijziel MR, Coebergh JW, Huijgens PC, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV (2014) Health-related quality of life and persistent symptoms in relation to (R-)CHOP14, (R-)CHOP21, and other therapies among patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results of the population-based PHAROS-registry. Ann Hematol 93:1705–1715

Olivieri A, Gini G, Bocci C, Montanari M, Trappolini S, Olivieri J, Brunori M, Catarini M, Guiducci B, Isidori A, Alesiani F, Giuliodori L, Marcellini M, Visani G, Poloni A, Leoni P (2012) Tailored therapy in an unselected population of 91 elderly patients with DLBCL prospectively evaluated using a simplified CGA. Oncologist 17:663–672

Pallis AG, Wedding U, Lacombe D, Soubeyran P, Wildiers H (2010) Questionnaires and instruments for a multidimensional assessment of the older cancer patient: what clinicians need to know? Eur J Cancer 46:1019–1025

Pasetto LM, Falci C, Compostella A, Sinigaglia G, Rossi E, Monfardini S (2007) Quality of life in elderly cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 43:1508–1513

Puts MT, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Springall E, Alibhai SM (2012) Use of geriatric assessment for older adults in the oncology setting: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 104:1133–1163

Puts MT, Santos B, Hardt J, Monette J, Girre V, Atenafu EG, Springall E, Alibhai SM (2014) An update on a systematic review of the use of geriatric assessment for older adults in oncology. Ann Oncol 25:307–315

Rinaldi P, Mecocci P, Benedetti C, Ercolani S, Bregnocchi M, Menculini G, Catani M, Senin U, Cherubini A (2003) Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:694–698

Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, Roth C, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG, Sloss EM, Wenger NS (2001) The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 49:1691–1699

Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E (2011) Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 105:1684–1692

Soubeyran P, Fonck M, Blanc-Bisson C, Blanc JF, Ceccaldi J, Mertens C, Imbert Y, Cany L, Vogt L, Dauba J, Andriamampionona F, Houede N, Floquet A, Chomy F, Brouste V, Ravaud A, Bellera C, Rainfray M (2012) Predictors of early death risk in older patients treated with first-line chemotherapy for cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 30:1829–1834

Soubeyran P, Khaled H, MacKenzie M, Debois M, Fortpied C, de Bock R, Ceccaldi J, de Jong D, Eghbali H, Rainfray M, Monnereau A, Zulian G, Teodorovic I (2011) Diffuse large B-cell and peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in the frail elderly. A phase II EORTC trial with a progressive and cautious treatment emphasizing geriatric assessment. Geriatr Oncol Rep 2:36–44

Spina M, Balzarotti M, Uziel L, Ferreri AJ, Fratino L, Magagnoli M, Talamini R, Giacalone A, Ravaioli E, Chimienti E, Berretta M, Lleshi A, Santoro A, Tirelli U (2012) Modulated chemotherapy according to modified comprehensive geriatric assessment in 100 consecutive elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncologist 17:838–846

Tinquaut F, Freyer G, Chauvin F, Gane N, Pujade-Lauraine E, Falandry C (2016) Prognostic factors for overall survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer treated with chemotherapy: results of a pooled analysis of three GINECO phase II trials. Gynecol Oncol 143:22–26

Tucci A, Ferrari S, Bottelli C, Borlenghi E, Drera M, Rossi G (2009) A comprehensive geriatric assessment is more effective than clinical judgment to identify elderly diffuse large cell lymphoma patients who benefit from aggressive therapy. Cancer 115:4547–4553

Tucci A, Martelli M, Rigacci L, Riccomagno P, Cabras MG, Salvi F, Stelitano C, Fabbri A, Storti S, Fogazzi S, Mancuso S, Brugiatelli M, Fama A, Paesano P, Puccini B, Bottelli C, Dalceggio D, Bertagna F, Rossi G, Spina M, Italian Lymphoma F (2015) Comprehensive geriatric assessment is an essential tool to support treatment decisions in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a prospective multicenter evaluation in 173 patients by the Lymphoma Italian Foundation (FIL). Leuk Lymphoma 56:921–926

van der Poel MW, Oerlemans S, Schouten HC, Mols F, Pruijt JF, Maas H, van de Poll-Franse LV (2014) Quality of life more impaired in younger than in older diffuse large B cell lymphoma survivors compared to a normative population: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Ann Hematol 93:811–819

Vellas B, Villars H, Abellan G, Soto ME, Rolland Y, Guigoz Y, Morley JE, Chumlea W, Salva A, Rubenstein LZ, Garry P (2006) Overview of the MNA—its history and challenges. J Nutr Health Aging 10:456–463 discussion 463-455

Wedding U, Pientka L, Hoffken K (2007) Quality-of-life in elderly patients with cancer: a short review. Eur J Cancer 43:2203–2210

Wedding U, Rohrig B, Klippstein A, Brix C, Pientka L, Hoffken K (2007) Co-morbidity and functional deficits independently contribute to quality of life before chemotherapy in elderly cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 15:1097–1104

Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M, Falandry C, Artz A, Brain E, Colloca G, Flamaing J, Karnakis T, Kenis C, Audisio RA, Mohile S, Repetto L, Van Leeuwen B, Milisen K, Hurria A (2014) International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32:2595–603

Wildiers H, Mauer M, Pallis A, Hurria A, Mohile SG, Luciani A, Curigliano G, Extermann M, Lichtman SM, Ballman K, Cohen HJ, Muss H, Wedding U (2013) End points and trial design in geriatric oncology research: a joint European organisation for research and treatment of cancer—Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology—International Society of Geriatric Oncology position article. J Clin Oncol 31:3711–3718

Yoshida M, Nakao T, Horiuchi M, Ueda H, Hagihara K, Kanashima H, Inoue T, Sakamoto E, Hirai M, Koh H, Nakane T, Hino M, Yamane T (2016) Analysis of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: aggressive therapy is a reasonable approach for ‘unfit’ patients classified by comprehensive geriatric assessment. Eur J Haematol 96:409–416

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG, Mundipharma Medical Company (Schweiz), and Celgene GmbH. The authors thank the patients, their families, and the clinicians for contribution to the trial as well as the staff from participating sites and Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) Coordinating Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Karin Ribi and Kerri Clough-Gorr designed the C-SGA and QoL part of the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. Stéphanie Rondeau analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Felicitas Hitz and Ulrich Mey designed the clinical study and performed the research. Milica Enoiu, Thomas Pabst, Anastasios Stathis, and Natalie Fischer performed the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 168 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ribi, K., Rondeau, S., Hitz, F. et al. Cancer-specific geriatric assessment and quality of life: important factors in caring for older patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. Support Care Cancer 25, 2833–2842 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3698-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3698-4