Abstract

The objective of this study was to compare health-related quality of life (HRQOL) between diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) survivors of different age categories (18–59/60–75/76–85 years) and to compare their HRQOL with an age- and sex-matched normative population. The population-based Eindhoven Cancer Registry was used to select all patients diagnosed with DLBCL from 1999 to 2010. Patients (n = 363) were invited to complete the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) questionnaire, and 307 survivors responded (85 %). Data from an age- and sex-matched normative population (n = 596) were used for comparison. DLBCL survivors aged 18–59 years scored better on physical functioning, quality of life, appetite loss and constipation than survivors of 76–85 years old (all p < 0.05). Financial problems more often occurred in survivors aged 18–59 years compared to survivors of 76–85 years old (p < 0.01). Compared to the normative population, DLBCL survivors aged 18–59 years showed worse scores on cognitive and social functioning and on dyspnea and financial problems (p < 0.01, large- and medium-size effects). In survivors of the other age categories, only differences with trivial or small-size effects were found. Although younger DLBCL survivors have better HRQOL than older survivors, the differences found between younger survivors and normative population were the largest. This suggests that having DLBCL has a greater impact on younger than older survivors and that the worse HRQOL observed in older DLBCL survivors in comparison with younger survivors is caused mostly by age itself and not by the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the Netherlands, approximately 1,572 patients were newly diagnosed with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the year 2007, and this number is expected to increase to almost 1,900 in the year 2020. More than 50 % of them are older than 50 years at the time of diagnosis. The 10-year prevalence of aggressive NHL, with 6,570 patients in the year 2009, is expected to increase to approximately 10,600 patients in 2020 [1].

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of aggressive B cell NHL with a median age at diagnosis of over 60 years. There is an increasing number of DLBCL survivors due to effective treatments and the aging of the population. A patient is defined as a cancer survivor from the time of diagnosis through the rest of his life [2].

Several studies show that treatment with standard chemotherapy in combination with rituximab improves complete remission rates and also survival in elderly DLBCL patients [3–6]. However, in daily clinical practice, elderly patients less often receive standard chemotherapy schedules in comparison with younger patients [5–7]. Reasons for suboptimal treatment are, amongst others, co-morbidity and poor performance status, and also high age in itself is considered by doctors as a reason to not give standard treatment [5–9]. Furthermore, the effect of cancer treatment on the quality of life of elderly patients is an important concern.

There is a growing interest in the impact of disease-related effects of NHL and its treatment on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of (elderly) NHL survivors. Several studies showed that having NHL is accompanied by deterioration in various domains of HRQOL [10–18]. Although there are indications that HRQOL improves after treatment [10–13, 16], there are also indications that it remains reduced in comparison with the general population [15]. Little is known about age-related differences in HRQOL amongst DLBCL survivors.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were to compare HRQOL between DLBCL survivors younger than 60 years, those aged 60 to 75 years and those older than 75 years, to assess age-related differences and to identify possible associations between socio-demographic and clinical characteristics with HRQOL. Furthermore, we compared the HRQOL of DLBCL survivors with an age-matched general population to distinguish between the impact of DLBCL on HRQOL and impact of age itself on HRQOL. We hypothesize that HRQOL is more impaired in older survivors in comparison with younger survivors and that HRQOL is worse amongst DLBCL survivors in comparison with the normative population.

Methods

Setting and population

This study is part of a dynamic population-based survey amongst NHL survivors registered with the Eindhoven Cancer Registry (ECR) of the Comprehensive Cancer Centre South (CCCS). The ECR records data on all patients who are newly diagnosed with cancer in the southern part of the Netherlands, an area with 2.3 million inhabitants, 18 hospital locations and 2 large radiotherapy institutes. The ECR was used to select all patients who were diagnosed with DLBCL between 1 January 1999 and 12 January 2010. We included all patients with DLBCL as defined by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology-3 codes (ICD-O-3) [19].

Participants aged ≥85 years were excluded, because it was expected that they would have difficulty in completing self-administered questionnaires without assistance. Excluding all patients who had died, our database was linked with the database of the Central Bureau for Genealogy, which collects data on all deceased Dutch citizens through the civil municipal registries. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from a local, certified medical ethics committee.

Data collection

Data collection was done within PROFILES (Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long-term Evaluation of Survivorship). PROFILES is a registry for the study of physical and psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatment from a dynamic, growing population-based cohort of both short- and long-term cancer survivors. PROFILES contains a large web-based component and is linked directly to clinical data from ECR. Details of the data collection method have been previously described [20].

In May 2009, patients between 6 months and 10 years after diagnosis received the first questionnaire. Patients were included from 6 months after diagnosis to minimize the direct effect of the primary treatment, which takes place around the first 6 months after diagnosis, on the study results. In November 2009, patients diagnosed between May 2008 and May 2009 were invited to participate, and in May 2011, patients diagnosed between May 2009 and December 2010 were invited to participate.

In 2009, our research group assigned CentERdata (www.centerdata.nl), a research institute at Tilburg University, to collect normative data on HRQOL via the CentERpanel. The CentERpanel is an online household panel consisting of over 2,000 households which are representative of the Dutch-speaking population in the Netherlands. For households without internet access, additional provisions were provided to assist in data collection. Of the 1,731 cancer-free panel members of ≥18 years who completed the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [21], 596 could be age- and sex-matched with our DLBCL sample. For matching, ten strata were formed using sex and age (five categories). Within each stratum, a maximum number of cancer-free panel members were randomly matched according to the “strata frequency distribution” of the patients. This resulted in 596 matched cancer-free panel members for 307 patients.

Study measures

The validated Dutch version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 was used to assess HRQOL. This is a self-report questionnaire developed by the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer for assessing the quality of life in cancer patients. The questionnaire includes five scales on physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning; a global health status/quality of life scale; three symptom scales on fatigue, nausea and vomiting and pain; and six single items assessing dyspnea, sleeping problems, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea and financial problems. Answer categories range from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). After linear transformation, all scales and single-item measures range in score from 0 to 100. A higher score on the functional scales and global health and quality of life scale means a better HRQOL, whereas a higher score on the symptom scales refers to more symptoms [22].

Co-morbidity at the time of survey was categorized according to the adapted Self-Administered Co-Morbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) [23].

Survivors' educational level and marital status was also assessed in the questionnaire. Clinical information was available from the ECR that routinely collects data on tumour characteristics, including date of diagnosis, tumour grade, histology, Ann Arbor stage, primary treatment and patients' background characteristics, including gender and date of birth.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1 for Windows; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Clinical important differences were determined using the evidence-based guidelines for interpretation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 [24]. The size effect as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 is divided into four size classes: large (one representing unequivocal clinical relevance), medium (likely to be clinically relevant, but to a lesser extent), small (subtle but, nevertheless, clinically relevant) and trivial (circumstances unlikely to have any clinical relevance or where there was no difference). Patients and respondents of the normative population were categorized into three age groups, namely, younger than 60 years, 60–75 years and older than 75 years.

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between respondents, non-respondents and patients with unverifiable addresses were compared with analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables.

The mean EORTC QLQ-C30 scores between different age groups of DLBCL survivors were compared using ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc tests.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were carried out to compare the mean EORTC QLQ-C30 scores in the DLBCL survivors with the normative population adjusted for sex, age and co-morbidity.

Results

Patients' characteristics and normative population

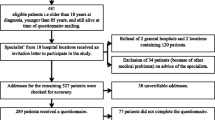

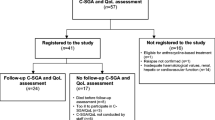

Questionnaires were sent to 363 DLBCL survivors, and 307 completed questionnaires were returned (85 % response rate) (Fig. 1). The mean age at the time of survey completion was 63.7 years with a mean time since diagnosis of 3.4 years. Sixty-five percent was male, and 80 % had a partner. Almost all patients were treated with chemotherapy (95 %), and 29 % received radiotherapy.

Compared to respondents, non-respondents were more often female (35 versus 55 %; p < 0.01), and patients with unverifiable addresses more often did not receive chemotherapy as primary treatment (95 versus 85 %; p = 0.05). No significant differences between respondents, non-respondents and patients with unverifiable addresses were observed for age, years since diagnosis and stage at diagnosis (data not shown).

With respect to the age- and sex-matched normative population, mean age at survey completion was 63.5 years, and 67 % was male. Seventy-seven percent had a partner. Almost two thirds (64 %) of respondents reported one or more co-morbid conditions, the most common were hypertension, back pain and arthritis. Of the 596 participants, 192 participants were younger than 60 years, 268 participants were aged 60–75 years and 136 participants were older than 75 years (Table 1).

DLBCL survivors aged 18–59 years reported more often no co-morbid conditions and less often more than two co-morbid conditions in comparison with survivors of 76–85 years old (p < 0.05). The most frequently reported co-morbid conditions were arthritis, back pain, hypertension and heart conditions. All these conditions were less common in respondents between 18 and 59 years old (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found between the three age categories regarding years since diagnosis, stage at diagnosis or primary treatment (Table 2).

Comparison between younger and older DLBCL survivors and normative population

A comparison between patients in the three age categories (18–59/60–75/75–85 years) showed that survivors aged 18–59 years scored better on physical functioning (p < 0.01), global health status/quality of life (p < 0.05), appetite loss (p < 0.01) and constipation (p < 0.05) than survivors aged 76–85 years (Table 3). Furthermore, survivors in the age of 60–75 years scored better on global health status/quality of life (p < 0.05) and appetite loss (p < 0.01) in comparison with survivors of 76–85 years old. The size effects of these differences were all trivial or small. Financial problems more often occurred in survivors of 18–59 years old compared to survivors in the age of 76–85 years, and this difference has of medium size effect (p < 0.01).

Compared to an age- and sex-matched normative population, DLBCL survivors of 18–59 years old showed worse scores with a large-size effect on cognitive functioning and social functioning (p < 0.01; Fig. 2a). Furthermore, there was a small-size effect regarding worse scores in physical and role functioning in comparison with the normative population (p < 0.01). In survivors aged 60–75 and 76–85 years, worse scores with a small-size effect were observed on all EORTC QLQ-C30 functional scales except for global quality of life and emotional functioning in survivors of 76–85 years old (p < 0.01; Fig. 2b, c).

With regard to EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scores, survivors aged 18–59 years old more often reported dyspnea and financial problems (p < 0.01, medium-size effect) and fatigue and sleeping problems (p < 0.01, small-size effect) in comparison with the normative population (Fig. 3a). A small size effect was observed in survivors between 60 and 75 years with worse scores on fatigue, nausea and vomiting, dyspnea, sleeping problems and financial problems (p < 0.01; Fig. 3b). Survivors between 76 and 85 years reported more often fatigue, dyspnea, sleeping problems and appetite loss than the normative population. These differences had a small-size effect (p < 0.01; Fig. 3c).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare HRQOL between younger and older DLBCL survivors and to compare this with the HRQOL of an age- and sex-matched normative population. In all three age categories, deteriorations in several domains of EORTC QLQ-C30 functioning scales were observed. The largest differences were observed between survivors of 18–59 years old and the normative population with regard to social and cognitive functioning. These results indicate that being diagnosed with and treated for DLBCL has a greater impact with respect to functional status on patients aged 18–59 years than for the elderly in comparison with the age- and sex-matched normative population. This was also found in other studies that compared the quality of life between younger and older survivors with different types of malignancies [25, 26]. A possible explanation for the differences between younger and older survivors could be that, in the natural course of aging, a decline in functional status occurs. Furthermore, elderly survivors might have better coping strategies through more life experience, and they are likely to be faced with lower work-related and social demands.

However, we cannot exclude that the elderly DLBCL survivors participating in the present study received less aggressive treatment schedules than the younger survivors and that, therefore, their HRQOL is relatively well. With respect to cognitive functioning, there are studies suggesting that chemotherapy is associated with cognitive dysfunction, although these studies fail to show unequivocal results [27–31].

Differences in HRQOL between NHL survivors and the normative population are in line with previous studies [11, 12, 15, 32, 33]. In three studies, which included patients with and without active disease, it was observed that NHL survivors scored worse on various HRQOL domains in comparison to a normative population [12, 15, 32]. Another study showed that, in comparison with the general population, patients with active NHL scored lower on physical and mental health status, whereas disease-free individuals scored only worse on mental health status [11].

Younger DLBCL survivors experienced better physical functioning and global health status/quality of life in comparison with older survivors, although these differences had a trivial or small-size effect. Three other studies showed that elderly NHL survivors reported worse physical functioning, but better overall quality of life and mental health compared to younger survivors, although they often did not indicate whether the observed differences were of clinical relevance [14, 15, 33]. Since we observed that the differences in quality of life/global health status between DLBCL survivors in all three age categories and the normative population only had a small size effect, it seems that the worse quality of life/global health status found in older DLBCL survivors in comparison with younger survivors is caused mostly by age itself and not by the disease. Another explanation might be a cohort effect of this age group towards their appraisal of declining health and functional status, with elderly possibly having less high expectations towards their health.

With respect to EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales, financial problems occurred more often in survivors between 18 and 59 years in comparison with the normative population. These problems had a medium-size effect. Previous studies also mentioned that NHL survivors experience more financial difficulties in comparison with a normative population [12, 34]. Possible causes are problems in obtaining work, health insurance, life insurance and a mortgage [15, 35–37]. Of course, work-related problems affect younger survivors more, since older patients will probably be retired.

DLBCL survivors aged 18–59 years showed worse scores on dyspnea with a medium-size effect, which might be explained by the effect of treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy on cardiopulmonary function [3, 5, 7, 8, 38]. Especially, doxorubicin, the anthracycline mostly used in the treatment of DLBCL patients, is associated with a risk of cardiotoxicity [39]. Unfortunately, we do not have information on the chemotherapy schedules or doses patients received. Therefore, we cannot exclude that elderly patients received less anthracycline-based chemotherapy in comparison with younger patients.

The treatment of the first choice for both younger and older DLBCL patients is the R-CHOP regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone) [3, 4, 40]. Elderly NHL survivors more often do not receive standard treatment compared with younger survivors [5–8, 41]. This may contribute to the poorer survival of elderly patients [3–8, 38, 42]. Several studies show that high age in itself is stated by doctors as a reason for suboptimal treatment, even in the absence of a poor performance status [5–7]. It is often assumed that a standard treatment will lead to deterioration in HRQOL. The results in our study suggest that this is not the case. Therefore, treatment with chemotherapy and even intensive chemotherapy schedules should always be considered in elderly DLBCL patients. We cannot exclude, however, that in the present study, the elderly DLBCL survivors received less aggressive treatment schedules and that, therefore, their HRQOL is relatively well. This should be a focus for future studies.

The current study has some limitations. We lack detailed information about the exact primary treatment and the patients' response to this treatment, whether patients received additional treatment after their primary treatment or whether they received treatment at the time of completion of the questionnaire. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that a selection bias has occurred, amongst others, due to death of patients, since the respondents comprised only 53 % of eligible patients. At last, we cannot exclude that patients did not participate because of poor health or absence of symptoms. The strengths of our study are that we compare DLBCL survivors of different age categories with an age- and sex-matched normative population, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study investigating this. In addition, the study is performed in a population-based setting instead of a hospital-based setting, and there was a high response rate, which makes it possible to generalize the results.

In conclusion, although younger survivors score better on several domains of quality of life in comparison with elderly patients, the impact of DLBCL and its treatment is greater for younger survivors than for older survivors, when compared with an age- and sex-matched normative population. Especially, cognitive and social functioning was relatively more impaired in younger survivors, and financial problems and dyspnea more often occurred. Our results suggest that a decrease in HRQOL in elderly DLBCL survivors may not be the related to the primary treatment. Therefore, a premise of declining HRQOL may not be dominant in the choice of treatment.

References

KWF kankerbestrijding, Signaleringcommissie Kanker. Kanker in Nederland tot 2020. Trends and Prognoses (in Dutch). http://www.kwfkankerbestrijding.nl

US National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (2013) http://www.canceradvocacy.org. Accessed 29 May 2013

Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R et al (2002) CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 346(4):235–242

Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, Solal-Celigny P, Bouabdallah R, Ferme C et al (2005) Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol 23(18):4117–4126

van de Schans SA, Wymenga AN, van Spronsen DJ, Schouten HC, Coebergh JW, Janssen-Heijnen ML (2012) Two sides of the medallion: poor treatment tolerance but better survival by standard chemotherapy in elderly patients with advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 23(5):1280–1286

Peters FP, Lalisang RI, Fickers MM, Erdkamp FL, Wils JA, Houben SG et al (2001) Treatment of elderly patients with intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a retrospective population-based study. Ann Hematol 80(3):155–159

Thieblemont C, Grossoeuvre A, Houot R, Broussais-Guillaumont F, Salles G, Traulle C et al (2008) Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in very elderly patients over 80 years. A descriptive analysis of clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol 19(4):774–779

Peters FP, Fickers MM, Erdkamp FL, Wals J, Wils JA, Schouten HC (2001) The effect of optimal treatment on elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: more patients treated with unaffected response rates. Ann Hematol 80(7):406–410

Kobayashi Y, Miura K, Hojo A, Hatta Y, Tanaka T, Kurita D et al (2011) Charlson Comorbidity Index is an independent prognostic factor among elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 137(7):1079–1084

Heutte N, Haioun C, Feugier P, Coiffier B, Tilly H, Ferme C et al (2011) Quality of life in 269 patients with poor-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab versus observation after autologous stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma 52(7):1239–1248

Smith SK, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Zebrack BJ (2009) Health status and quality of life among non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Cancer 115(14):3312–3323

Jerkeman M, Kaasa S, Hjermstad M, Kvaloy S, Cavallin-Stahl E (2001) Health-related quality of life and its potential prognostic implications in patients with aggressive lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group Trial. Med Oncol 18(1):85–94

Merli F, Bertini M, Luminari S, Mozzana R, Berte R, Trottini M et al (2004) Quality of life assessment in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with anthracycline-containing regimens. Report of a prospective study by the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. Haematologica 89(8):973–978

Smith SK, Crespi CM, Petersen L, Zimmerman S, Ganz PA (2010) The impact of cancer and quality of life for post-treatment non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Psychooncology 19(12):1259–1267

Mols F, Aaronson NK, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, Vreugdenhil G, Lybeert ML et al (2007) Quality of life among long-term non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors: a population-based study. Cancer 109(8):1659–1667

Doorduijn J, Buijt I, Holt B, Steijaert M, Uyl-de Groot C, Sonneveld P (2005) Self-reported quality of life in elderly patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy. Eur J Haematol 75(2):116–123

Persson L, Larsson G, Ohlsson O, Hallberg IR (2001) Acute leukaemia or highly malignant lymphoma patients' quality of life over two years: a pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 10(1):36–47

Geffen DB, Blaustein A, Amir MC, Cohen Y (2003) Post-traumatic stress disorder and quality of life in long-term survivors of Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Israel. Leuk Lymphoma 44(11):1925–1929

Fritz APC, Jack A et al (2000) International classification of diseases for oncology, 3rd edn. World Health Organisation, Geneva

van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, Denollet J, Roukema JA, Aaronson NK et al (2011) The Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer 47(14):2188–2194

van de Poll-Franse LV, Mols F, Gundy CM, Creutzberg CL, Nout RA, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM et al (2011) Normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC-sexuality items in the general Dutch population. Eur J Cancer 47(5):667–675

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ et al (1993) The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376

Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN (2003) The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 49(2):156–163

Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G, Martyn St-James M, Fayers PM, Brown JM (2011) Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 29(1):89–96

Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J, Walsh RA, James EL, Girgis A (2012) Young adult cancer survivors' psychosocial well-being: a cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Support Care Cancer 20(6):1333–1341

Bifulco G, De Rosa N, Tornesello ML, Piccoli R, Bertrando A, Lavitola G et al (2012) Quality of life, lifestyle behavior and employment experience: a comparison between young and midlife survivors of gynecology early stage cancers. Gynecol Oncol 124(3):444–451

Wefel JS, Saleeba AK, Buzdar AU, Meyers CA (2010) Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer 116(14):3348–3356

Hermelink K, Untch M, Lux MP, Kreienberg R, Beck T, Bauerfeind I et al (2007) Cognitive function during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: results of a prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Cancer 109(9):1905–1913

Schagen SB, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Rosenbrand RM, van Rhijn D, Rodenhuis S et al (2002) Late effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognitive function: a follow-up study in breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 13(9):1387–1397

Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, Davis RN, Meyers CA (2004) The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer 100(11):2292–2299

Donovan KA, Small BJ, Andrykowski MA, Schmitt FA, Munster P, Jacobsen PB (2005) Cognitive functioning after adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for early-stage breast carcinoma. Cancer 104(11):2499–2507

Jensen RE, Arora NK, Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Hamilton AS, Aziz NM et al (2013) Health-related quality of life among survivors of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 119(3):672–680

Zebrack BJ, Yi J, Petersen L, Ganz PA (2008) The impact of cancer and quality of life for long-term survivors. Psychooncology 17(9):891–900

Brandt J, Dietrich S, Meissner J, Neben K, Ho AD, Witzens-Harig M (2010) Quality of life of long-term survivors with Hodgkin lymphoma after high-dose chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation, and conventional chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 51(11):2012–2020

Mols F, Thong MS, Vissers P, Nijsten T, van de Poll-Franse LV (2012) Socio-economic implications of cancer survivorship: results from the PROFILES registry. Eur J Cancer 48(13):2037–2042

Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JW, Vreugdenhil G, Aaronson NK, Lybeert ML et al (2006) Better quality of life among 10–15 year survivors of Hodgkin's lymphoma compared to 5–9 year survivors: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 42(16):2794–2801

Mols F, Thong MS, Vreugdenhil G, van de Poll-Franse LV (2009) Long-term cancer survivors experience work changes after diagnosis: results of a population-based study. Psychooncology 18(12):1252–1260

Hasselblom S, Stenson M, Werlenius O, Sender M, Lewerin C, Hansson U et al (2012) Improved outcome for very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the immunochemotherapy era. Leuk Lymphoma 53(3):394–399

Hershman DL, McBride RB, Eisenberger A, Tsai WY, Grann VR, Jacobson JS (2008) Doxorubicin, cardiac risk factors, and cardiac toxicity in elderly patients with diffuse B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 26(19):3159–3165

Lee L, Crump M, Khor S, Hoch JS, Luo J, Bremner K et al (2012) Impact of rituximab on treatment outcomes of patients with diffuse large b-cell lymphoma: a population-based analysis. Br J Haematol 158(4):481–488

Lin TL, Kuo MC, Shih LY, Dunn P, Wang PN, Wu JH et al (2012) The impact of age, Charlson comorbidity index, and performance status on treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol 91(9):1383–1391

Griffiths RI, Gleeson ML, Mikhael J, Dreyling MH, Danese MD (2012) Comparative effectiveness and cost of adding rituximab to first-line chemotherapy for elderly patients diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer 118(24):6079–6088

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and their doctors for their participation in the study. Special thanks go to Dr. M. van Bommel for independent advice and answering questions of patients. The following hospitals provided cooperation: Catharina Hospital, Eindhoven; Jeroen Bosch Hospital, 's-Hertogenbosch; Maxima Medical Centre, Eindhoven and Veldhoven; Sint Anna Hospital, Geldrop; St. Elisabeth Hospital, Tilburg; TweeSteden Hospital, Tilburg; VieCurie Hospital, Venlo and Venray; and Hospital Bernhoven, Oss. This work was supported by the Jonker-Driessen Foundation and ZonMW, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development and through PHAROS (Population-based HAematological Registry for Observational Studies) (#80-82500-98-01007). Dr. Lonneke van de Poll-Franse is supported by a Cancer Research Award from the Dutch Cancer Society (#UVT-2009-4349).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This study has been approved by the appropriate ethics committee and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van der Poel, M.W.M., Oerlemans, S., Schouten, H.C. et al. Quality of life more impaired in younger than in older diffuse large B cell lymphoma survivors compared to a normative population: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Ann Hematol 93, 811–819 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1980-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-013-1980-1