Abstract

Purpose

Breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors (AI) often experience side effects of joint pain, stiffness, or achiness (arthralgia). This study presents findings from a qualitative study of survivors on an AI regarding their knowledge of potential joint pain side effects and how both AI side effects and their management through moderate physical activity could be discussed during routine visits with their oncology provider.

Methods

Qualitative data from semi-structured interviews were content analyzed for emergent themes. Descriptive statistics summarize sample characteristics.

Results

Our sample included 36 survivors, mean age of 67 (range 46–87); 86 % Caucasian and 70 % had education beyond high school. AI experience are as follows: 64 % anastrozole/Arimidex, 48 % letrozole/Femara, and 31 % exemestane/Aromasin. Participants expressed interest in having more information about potential joint pain side effects when the AI was prescribed so they could understand their joint symptoms when they appeared or intensified. They were relieved to learn that their joint symptoms were not unusual or “in their head.” Participants would have been especially motivated to try walking as a way to manage their joint pain if physical activity had been recommended by their oncologist.

Conclusions

Breast cancer survivors who are prescribed an AI as part of their adjuvant treatment want ongoing communication with their oncology provider about the potential for joint pain side effects and how these symptoms may be managed through regular physical activity. The prescription of an AI presents a “teachable moment” for oncologists to recommend and encourage their patients to engage in regular physical activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a disease of aging, with an average age at diagnosis of 61 years [1]. In postmenopausal women, most breast cancer tumors are hormone receptor-positive [2, 3] and most of these patients will receive adjuvant endocrine treatment that includes an aromatase inhibitor (AI) to dramatically improve their overall prognosis and survival [4, 5]. Adjuvant AI therapy is recommended for 5 years, with recent evidence suggesting benefits from an additional 5 years [5]. Non-inflammatory joint pain, stiffness, and achiness (arthralgia) are common side effects of AIs, affecting an estimated 33 to 74% of women on this treatment [6–12]. Arthralgia symptoms range from mild to severe but are especially troublesome for women who report moderate to severe discomfort—an estimated 70 % of women reporting joint symptoms [7, 12]. Symptom onset is generally within 6 weeks to 12 months after AI initiation but can take longer, and symptoms may appear abruptly or increase gradually over time [7, 13]. Symptoms cease upon AI discontinuation [6, 7].

Patients generally learn about the potential for musculoskeletal side effects within a larger presentation of the benefits and risks of AI treatment. This communication takes place at the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis, when the overall treatment plan is discussed between the patient and the oncology provider team. AI benefits and risks are then revisited when the patient has completed all other treatments and is ready to initiate adjuvant endocrine therapy. During the first 2 years of endocrine treatment, it is recommended that patients be seen by the oncologist every 3 to 6 months to monitor treatment tolerance and manage side effects as they arise.

Our research team has conducted two related studies pertaining to the potential management of AI-associated arthralgia through moderate-intensity physical activity—a recently completed pilot test of the intervention [14] and an ongoing National Cancer Institute-funded randomized controlled trial (RCT) [15]. Both studies focus exclusively on women on AI therapy who report more than mild joint symptoms and who do not exercise at least 150 min per week. In addition, both studies include a qualitative component to explore ways in which our physical activity intervention—the Arthritis Foundation’s evidence-based Walk With Ease (WWE) program [16–18]—could be adapted for breast cancer survivors on AI therapy who are experiencing joint symptoms and implemented in clinical practice [15]. Here, we report findings regarding the following research question: From the patient’s perspective, how should oncology providers communicate with their patients about the risks of AI-associated arthralgia and its potential management through moderate-intensity physical activity?

Methods

Qualitative research methodology was used to collect data through semi-structured interviews with breast cancer survivors on AI therapy. The study protocol was approved by the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Participants and procedures

Potential study participants were identified through a review of medical records for patients scheduled to be seen in breast cancer clinics at a university-based hospital. Oncology providers provided approval for patients to be approached and screened by research staff. Inclusion criteria for both of the walking intervention studies (pilot and RCT) were (a) Stage I, II, or III breast cancer diagnosis; (b) currently on AI therapy; (c) self-reported joint pain, stiffness, or achiness; (d) engagement in less than 150 min of physical activity a week; (e) ability to engage in moderate-intensity physical activity; and (f) English speaking. Exclusion criteria were (a) significant medical conditions that limit their ability to participate in physical activity, (b) surgery or chemotherapy scheduled within the study period, (c) engagement in more than 150 min of physical activity a week, and (d) very mild or no adverse joint symptoms. Patients recruited into the study received a $45 gift card after they had completed all study requirements.

Data collection and analysis

Participants completed questionnaires at baseline regarding their demographics, cancer treatment history, height, and weight. Semi-structured interviews with study participants lasted no more than 30 min and were conducted primarily by telephone and for two participants in person. Members of the interview team included the interviewer and note taker as well as patient advocates and other members of the research team, depending on their availability. The study participant was introduced to all research team members attending the interview before it started. One research team member served as the interviewer and asked all of the questions in the semi-structured interview protocol; others attending the interview were asked at the end whether they had any further questions for the study participant. Two members of the research team alternated as interviewer.

After the interview was completed, the research team members who participated in the interview immediately held a debrief session at which they reviewed key insights from the interview. The note taker typed up the interview notes, which were then reviewed and edited for accuracy and completeness by others who participated in the interview. After all interviews were completed, each research team member read the full set of interview notes and independently conducted a content analysis of the interview data. We employed a conventional content analysis [19] because our aim was to create a basic description of the opinions and feelings of women on aromatase inhibitors with regard to their experiences with AI-associated pain and physical activity as a potential way to manage this pain. This type of analytic design is appropriate when existing theory or research literature on a phenomenon is limited, or in this case, is non-existent. The seven questions in the interview protocol pertained to themes that were salient to our research questions. The study participants were not very verbose but remarkably articulate when they answered each question, so we had limited but clear text from which to derive key points and themes. Because of this, the use of qualitative coding was unnecessary. After this independent review, the research team members then met to collectively review their respective interpretations and inductively derive overarching themes across all interview topics. There was a consensus on the major themes in the data. Descriptive statistics were generated from baseline questionnaires to characterize the sample.

Interview questions

An important aspect of the adaptation of WWE for breast cancer patients [15] was the development of an informative and motivational brochure that includes a section pertaining to AI-associated arthralgia. To gather patient perspectives on the content for this section, we asked study participants “What, if anything, did you know about potential joint pain side effects of AI therapy prior to hearing about our study?” We also asked “When did you first learn of this potential side effect of AI therapy?” and “How much detail about this potential side effect would you like to see in this brochure and how would you like it presented?” Our objective was to see if the brochure needed to fill any informational gaps between what study participants had received from their oncology provider and what they still wanted to know. We also explored study participant perspectives on what they learned about potential joint pain side effects and when they learned about these issues from their oncology provider, the Internet, other patients, or other sources. These questions pertained to future dissemination and implementation of the walking program in clinical practice.

Specifically with regard to our physical activity intervention, we also queried study participants about motivations for trying a walking program to manage AI-associated arthralgia, with questions focused on communications with oncology providers:

-

“Would you be especially motivated to start or continue walking if your oncologist “prescribed” walking or would it be enough if your oncologist “highly recommended” walking?

-

At what point during cancer treatment do you think this advice to start or continue walking should be given to the breast cancer patient?

-

Would it be helpful for the oncologist or his/her staff to remind you about the importance of walking when you come in for a clinic visit? How often would this reminder be helpful—every clinic visit, once a year, something else?

-

Do you think it would be helpful for family practice or general practice physicians to encourage their patients who are breast cancer survivors to start walking or continue walking?

Results

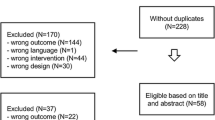

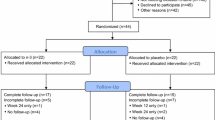

Screening, ineligibility, recruitment, and retention data are summarized in Fig. 1. A review of medical records identified 164 breast cancer survivors who were prescribed an AI and scheduled for a clinic appointment. During in-clinic screening, N = 13 patients were ineligible because of AI-related issues—they had not started taking their prescribed AI, were not adherent to their prescription, or were about to complete their 5 years of AI therapy. Thirty-four patients were considered by their treating oncologist as inappropriate for the study at this time for medical or psychosocial reasons. After screening by study staff, 64 patients did not meet eligibility criteria: N = 28 had no or low joint pain/stiffness/achiness, N = 19 were already physically active at guideline-recommended levels, and N = 17 had both no/low joint symptoms and high activity levels. Of the remaining 53 patients approached by the study staff, 8 declined to participate in the study. Of the 45 patients who consented to participate, 36 (80 %) completed the study requirements and comprise the final sample for our study; baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 67 (range 46 to 87), most were white (86 %), and 30 % had a high school degree or less. Mean body mass index (BMI) was 29 (range 19 to 41). Cancer treatments prior to adjuvant AI were 67 % chemotherapy, 75 % radiation therapy, 77 % lumpectomy, and 81 % mastectomy. The most commonly prescribed AI was anastrozole (Arimidex) (64 %), followed by letrozole (Femara) (48 %) and exemestane (Aromasin) (31 %), with some participants having tried more than one AI.

Knowledge and communications about AI-associated joint symptoms

Study participants were asked about their knowledge of potential joint pain side effects of AI therapy prior to participating in our study and reading our informational brochure. Participants recalled their oncologist informing them of potential AI side effects “during a detailed discussion of my treatment plan” (patient 3, age 68), “prior to starting the AI” (patient 4, age 70), “Dr. X has mentioned potential side effects several times” (patient 18, age 73), and “I asked about side effects” (patient 16, age 73). Others recalled the discussion occurring when they switched to a different AI to relieve their symptoms. Some study participants talked with other breast cancer survivors or read information on the Internet. However, for many study participants, the discussion of side effects did not resonate until their joint symptoms started—“The oncologist … might mention joint pain, but until you experience it you may not pay attention” (patient 11, age 63). When study participants started to experience new or particularly intense joint symptoms, they felt overwhelmed or unprepared—“You go through so much treatment and just when you think it is over, it’s not … now suddenly I feel very old … really alienated with a lot of pain” (patient 13, age 51), and “I am 46 and walking like an 80 year old” (patient 20, age 46). Despite being informed of potential joint pain side effects, many did not make the connection to their own joint symptom and attributed them to other causes such as advancing age, weight gain (“I thought my stiffness was because I was getting fatter”) (patient 14, age 54), arthritis (“It’s just old Arthur”) (patient 21, age 54), or the AI caused arthritis. They felt reassured when they learned they were not alone in experiencing joint symptoms—“It’s nice to know it is not in my head” (patient 13, age 51). Study participants wanted to know why and how the AI could cause joint pain, stiffness, or achiness, which is a difficult question for the oncology provider to answer because the precise etiology of AI arthralgia is still unclear [19, 20]. These comments suggest the importance of encouraging frequent provider-patient dialogue about potential joint pain side effects, especially during the first 2 years of AI therapy when joint symptoms are most likely to occur. In the absence of an ongoing dialogue, patients may attribute their new joint symptoms to other causes (misdiagnosis), become overly alarmed, or fail to ask their oncology provider about possible ways to manage their AI arthralgia.

Participants suggested that alerting patients to potential side effects can be lost in the oncology provider’s presentation of the survival benefits of taking an AI—“Oncologists need to emphasize the survivorship aspect of cancer, which is understandable” (patient 4, age 70) and “It is important not to anticipate side effects” (patient 5, age 72). However, they thought detailed discussions about potential joint pain side effects would not have discouraged them from taking an AI in light of its benefits for overall prognosis and survival—“I can live with the side effects if the gain is going to be good. This drug seemed to be a good one to start off with. I have talked to some who have had to switch pills because of side effects. The oncologist should be the one to deliver this message” (patient 10, age 72). Another participant said—“I would not have been frightened if the doctor told me that I might have some joint pain taking this med…. Pray to God and do what the doctor tells you” (patient 8, age 74). Study participants also suggested that women on AI therapy should feel encouraged to raise the issue with their oncology provider when they experienced joint symptoms—“Tell me what the drugs will do, tell me what the studies suggest, be honest with me … ask about the stuff beyond survival rates – ask what the treatment will do to you physically.” (patient 1, age 65). These comments underscore the importance patients place on the opinions and assurances of their oncology provider, including dialogues about common side effects. Some patients also felt that women on AI therapy should be proactive about initiating conversations about side effects with their oncology provider.

Communicating about exercise to reduce joint symptoms

In general, study participants knew they should be walking or otherwise engaging in physical activity for their physical well-being, mental health, and quality of life. When patients consented to our studies (pilot and RCT walking studies), they learned that our aim was to examine whether moderate-intensity physical activity could relieve their joint pain, stiffness, or achiness in the same way exercise can reduce arthritis pain and stiffness [16–18]; in this manner, they became aware of this potential benefit as well. Participants thought it would be especially influential or motivational if their oncology provider suggested or recommended they try walking to relieve AI-associated joint symptoms—“Anything coming from an oncologist … that person saved your life … I’m going to do what they say” (patient 14, age 54) and “Hopefully you trust your doctor and will do what they say” (patient 6, age 67). It was important for patients to have the oncologist’s approval for engaging in physical activity. One participant suggested how the oncologist could broach the topic during a discussion of potential AI side effects—“The AI could cause joint pain so, to be on the safe side, why not start walking as part of your daily routine” (patient 2, age 65). Another commented: “Let patients know they need to take their meds but will get along better and feel better if they exercise” (patient 11, age 66). These comments suggest a central role for oncology providers in encouraging their patients to be physically active, not only for joint symptom relief but for quality of life and survival as well.

Participants suggested oncology providers should ask their patients about walking or other types of physical activity during routine clinic visits, at least once a year, even noting physical activity levels in the patient’s medical chart—“If my oncologist had prescribed walking, I would have. I try to be positive and proactive. Reporting back to the oncologist would help me. I want to do everything I can to make my life better” (patient 9, age 66) and “I would have made a point to do it. Just like taking your medicine” (patient 10, age 69). Opinions regarding timing of the message to be physically active ranged from “right after the breast cancer diagnosis” (patient 12, age 51) to “after chemotherapy” (patient 15, age 71) or “when the AI was initially prescribed” (patient 4, age 70). One participant pulled it all together—“Maybe it would have been good to know about AI side effects. Would be good to have the doctor tell me about benefits of exercise, as well. Let patients know they need to take their meds but will get along better and feel better if they exercise” (patient 11, age 66). These comments suggest that whenever the message was delivered by the oncology provider, it was important to study participants that the message included some words of explanation and encouragement, not just a “please read this brochure” hand-out.

Most participants thought the recommendation to engage in regular physical activity would have the greatest impact if it came from their oncologist. However, they were also open to receiving the message come from other oncology providers—“Anyone who has the ability to let you know it could change your life – someone you have bonded with – they’ve seen everything I’ve gone through” (patient 19, age 49), “It does not matter who delivers the message so long as the source is credible” (patient 11, age 63), and “It is okay to hear more than one person sat – hey, make this part of your life” (patient 17, age 61). Some participants also thought it would be helpful if their general practitioner said “tell me about your joint pain” (patient 7, age 68) and encouraged them by saying “physical activity is important for cancer survivors” during routine clinic visits. As physical activity becomes recognized as an essential component of cancer care, these comments suggest exercise advocacy opportunities for a wide variety of medical providers.

Discussion

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a sample of 36 breast cancer survivors on AI therapy who were experiencing joint pain, stiffness, or achiness. We inquired about their knowledge of potential joint pain side effects of AI therapy and how both AI side effects and physical activity could be discussed during routine visits with their oncology provider. Most participants recalled being informed by their oncologist of the potential for musculoskeletal side effects during AI therapy; however, many did not connect these discussions of potential side effects with their own joint symptoms and attributed them to other causes such as aging, weight gain, or arthritis. This attribution of new joint pain to causes other than the AI can result in patients not raising the issue on their own during an oncology visit or not responding correctly to a general query about new symptoms rather than a specific query about joint pain, stiffness, or achiness. At every visit with the oncology provider, specific queries about joint symptoms may encourage patients to report new aches and pains in their joints and initiate a timely dialogue about possible causes and management options. Participants in our study were relieved to learn that their joint symptoms were not unusual or “in their head.” This suggests that when potential AI side effects are discussed with the patient, this presentation should include the prevalence of musculoskeletal side effects—such as 50 %—so that patients are reassured that joint symptoms are real and that their oncologist cares to know about this side effect. Participants did not think that knowing about potential joint pain side effects would have discouraged them from starting AI therapy.

Participants would have been especially motivated to try walking as a way to manage their joint symptoms if physical activity was recommended by their oncologist. As someone they credit with saving their life, the oncologist was an “authority” whose opinion mattered. They welcomed inquiries about both joint symptoms and engagement in physical activity during routine oncology visits. Having these discussions earlier rather than later—after symptoms started—was important. Because joint pain side effects can take months and even years to start or increase in severity [21], participants welcomed specific inquiries from their oncology provider about joint symptoms during routine clinic visits. Monitoring joint symptoms over time would help them clarify if the pain was new, increasing in intensity, potentially AI-associated, or more likely related to non-AI issues, such as arthritis or joint injury.

Encouraging cancer survivors to engage in recommended levels of physical activity—in general and as a way to manage AI-associated arthralgia—is a formidable challenge [22–24]. However, studies suggest a cancer diagnosis and various milestones during active treatment can present “teachable moments” to engage in recommended levels of physical activity, especially among women with a breast cancer diagnosis [25–29]. Our findings suggest that the moment an AI is prescribed could present a “teachable moment” by providing a link between moderate physical activity and the important quality of life concern of managing AI-associated joint pain [30].

Further, the teachable moment was specifically linked to the oncology provider and especially to the oncologist. Brief discourses about joint symptoms and engagement in physical activity needed to be more than just handing the patient a brochure, but they also need not be lengthy. Instead, study participants suggested that brief queries about joint pain and physical activity during routine clinic visits were more helpful than one lengthy conversation (that may be forgotten) when the AI was initially prescribed. These findings contribute to the literature pertaining to patients’ appreciation of communication with their oncology provider about the potential side effects of cancer treatments [31–33] and the nuances of oncology provider-patient communication [34, 35]. Our findings also underscore the need for oncology providers to take a more active role in encouraging guideline-recommended levels of physical activity to improve quality of life both during and after cancer treatment and enhance their patients’ overall prognosis and survival [36–40]. As AI-associated joint symptoms can take anywhere from weeks to years to manifest and increase in severity, it is important for the oncologist to explain the potential time course of arthralgia [21].

Our study had limitations. The interview sample was determined by the purposes of the pilot study and RCT, both of which had a specific focus on women on AI therapy who reported having more than moderate joint symptoms and engaging in less than guideline-recommended levels of physical activity. These recruitment criteria eliminated the possibility of hearing from insufficiently active women with mild joint pain, who may have had additional insights about communications about AI-arthralgia and physical activity. Further, the diversity of our sample reflected the patient population at the university-affiliated tertiary hospital where we conducted our studies and may differ from patients seen in community-based clinics. Provider-patient communication can be very nuanced, so it would be important for future qualitative research to focus specifically on understanding the perspectives of racial and ethnic minorities and women with a high school degree or less. Finally, the findings may be influenced by the fact that women in the study were those who were interested in being screened for a physical activity intervention, and therefore likely to have been motivated to become more active. Women without this motivation may have different insights to offer and should be studied in the future as well.

The option of AI therapy has greatly improved prognosis and survival rates among women with early stage breast cancer. Potentially, millions of women will be on this therapy for 5 years or longer. Living those survival years as pain free as possible—maintaining quality of life and physical function—is as important to cancer care as keeping breast cancer recurrence at bay [30]. For this large and growing segment of breast cancer survivors, it is important to offer interventions that are effective in relieving AI-associated joint symptoms as well as safe, enjoyable, and easy to do. Evidence regarding the potential for physical activity to relieve AI-associated arthralgia is still evolving. In our pilot study conducted among survivors age 65 or older, we found a 32 % decrease in joint stiffness (Cohen’s d effect size = 0.56; p = 0.07) between baseline and 6 weeks (end of intervention) and an increase from 21 to 50 % in the proportion of survivors who walked the targeted amount of 150 min per week (p < 0.001) [14]. More recently, findings from a recently published RCT of breast cancer survivors on AI therapy included a 29 % decrease in worst pain scores among women assigned to a 12-month exercise program as compared to a 3 % increase in worst pain in the usual care control group (p < 0.001) [41]. The exercise group also experienced significantly decreased pain severity and pain interference compared to the usual care group (p < 0.001) [41]. Other studies evaluating the potential benefits of exercise or movement in the management of AI-associated arthralgia include a pilot study of a yoga intervention [42]; pilot study of an 8-week, home-based program of resistance and aerobic exercises [43]; controlled trial of an aquatic exercise intervention [44]; and pilot study of a tai chi intervention [45].

As the evidence grows that walking and other forms of moderate-intensity exercise can reduce joint pain, stiffness, and achiness among survivors on AI therapy [14, 41], it will be important for oncology providers to discuss this non-pharmacological approach to joint symptom management and actively encourage their patients to engage in physical activity. Women in our interview sample welcomed brief discussions during routine clinic visits—a specific question about new or intensifying joint pain or stiffness and brief encouragement to try moderate physical activity to relieve the joint symptoms. This brief communication should be feasible during the clinic visit, especially during the first 2 years of AI therapy when joint symptoms are most likely to occur.

References

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER). All sites: cancer: SEER stat fact sheets. National Cancer Institute. 2014. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html. Accessed 01/15/14

Anderson WF, Pfeiffer RM, Dores GM, Sherman ME (2006) Comparison of age distribution patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15(10):1899–1905

Benz CC (2008) Impact of aging on the biology of breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 66(1):65–74

Taylor WC, Muss HB (2010) Adjuvant therapy for older women with breast cancer. Cancer J 16:289–293

Burstein HJ, Griggs JJ, Prestrud AA, Temin S (2010) American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline: update on adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 6(5):243–246

Boonstra A, van Zadelhoff J, Timmer-Bonte A, Ottevanger PB, Beurskens CHG, van Laarhoven HWM (2013) Arthralgia during aromatase inhibitor treatment in early breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 0(0):1–8

Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J et al (2007) Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25(25):3877–3883

Dizdar O, Ozcakar L, Malas FU, Harputluoglu H, Bulut N et al (2009) Sonographic and electrodiagnostic evaluations in patients with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia. J Clin Oncol 27(30):4955–4960

Oberguggenberger A, Hubalek M, Sztankay M, Meraner V, Beer B et al (2011) Is the toxicity of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy underestimated? Complementary information from patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Breast Cancer Res Treat 128(2):553–561

Presant CA, Bosserman L, Young T et al (2007) Aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia and/or bone pain: frequency and characterization in non-clinical trial patients. Clin Breast Cancer 7(10):775–778

Kanematsu M, Morimoto M, Honda J, Nagao T, Nakagawa M et al (2011) The time since last menstrual period is important as a clinical predictor of non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia. BMC Cancer 10(11):436

Mao JJ, Stricker C, Bruner D et al (2009) Patterns and risk factors associated with aromatase inhibitor-related arthralgia among breast cancer survivors. Cancer 115:3631–3639

Singer O, Cigler T, Moore AB, Levine AB, Hentel K et. al (2012) Defining aromatase inhibitor musculoskeletal symptom: a prospective study. Arth Care Res

Nyrop KA, Muss HB, Hackney B, Cleveland R, Altpeter M, Callahan LF (2015) Feasibility and promise of a 6-week program to encourage physical activity and reduce joint symptoms among elderly breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy. J Geriatr Oncol 5(2):148–155

Nyrop KA, Callahan LF, Rini C et al (2015) Adaptation of an evidence-based arthritis program for breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy who are experiencing joint pain. Prev Chronic Dis

Arthritis Foundation (2010) Walk with ease: your guide to walking for better health, improved fitness and less pain (Third edition). Arthritis Foundation, Atlanta

Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M et al (2011) Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation’s (AF) Walk With Ease (WWE) program. Arth Care Res 63(8):1098–1107

Nyrop KA, Cleveland R, Callahan LF (2014) Achievement of exercise objectives and satisfaction with the walk with ease program-group and self-directed participants. Am J Health Promot 28(4):228–230

Niravath P (2013) Aromatase-inhibitor-induced arthralgia: a review. Ann Oncol 24(6):1443–1449

Dent SF, Gaspo R, Kissner M, Prichard KI (2011) Aromatase inhibitor therapy: toxicities and management strategies in the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126:296–310

Castel LD, Hartmann KE, Mayer IA et al (2013) Time course of arthralgia among women initiating aromatase inhibitor therapy and a postmenopausal comparison group in a prospective cohort. Cancer 119(13):2317–2382

Eheman C, Henley J, Ballard-Barbash R, Jacobs EJ, Schymura MJ et al (2012) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2008, featuring cancers associated with excess weight and lack of sufficient physical activity. Cancer 118(9):2338–2366

Harrison S, Hayes SC, Newman B (2009) Level of physical activity and characteristics associated with change following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psycho-Oncology 18:387–394

Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K (2008) Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol 26:2198–2204

Sabiston CM, Brunet J, Vallance JK, Meterissian S (2014) Prospective examination of objectively assessed physical activity and sedentary time after breast cancer treatment: sitting on the crest of the teachable moment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev

Alfano CM, Day JM, Katz ML et al (2009) Exercise and dietary change after diagnosis and cancer-related symptoms in long-term survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 79804. Psychooncology 18(2):128–133

Humpel N, Magee C, Jones SC (2007) The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the health behaviors of cancer survivors and their family and friends. Support Care Cancer 15(6):621–630

Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson B, McBride C, Lipkus I, Clipp E (2000) Current health behaviors and readiness to pursue life-style changes among men and women diagnosed with early stage prostate and breast carcinomas. Cancer 88(3):674–684

Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM (2005) Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol 23(24):5814–5830

Olufade T, Gallicchio L, MacDonald R, Helzlsouer K (2015) Musculoskeletal pain and health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors. Support Care Cancer 23(2):447–455

Bender JL, Hohenadel J, Wong J et al (2008) What patients with cancer want to know about pain: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manag 35(2):177–187

Davidson B, Vogel V, Wickerham L (2007) Oncologist-patient discussion of adjuvant hormonal therapy in breast cancer: results of a linguistic study focusing on adherence and persistence to therapy. J Support Oncol 5(3):139–143

Kenyon M, Mayer DK, Owens AK (2014) Late and long-term effects of breast cancer treatment and surveillance management for the general practitioner. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 43(3):382–398

Jenkins V, Solis-Trapala I, Langridge C, Catt S, Talbot DC, Fallowfield LJ (2011) What oncologists believe they said and what patients believe they heard: an analysis of phase I trial discussions. J Clin Oncol 29(1):61–68

Yeom HE, Heidrich SM (2013) Relationships between three beliefs as barriers to symptom management and quality of life in older breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(3):E108–E118

Jones LW, Courneya KS (2002) Exercise discussions during cancer treatment consultations. Cancer Pract 10(2):66–74

Park J-H, Yoon YJ, Lee CW, Lee J, Oh M et al (2014) The effects of oncologists’ physical activity recommendations and information packages on level of physical activity and the quality of life in cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 32(5s):Abstract 9629

Ruiz-Casado A, Lucia A (2014) The time has come for oncologists to recommend physical activity to cancer survivors. Arch Exerc Health Dis 4(1):214–215

Santa Mina D, Alibhai SM, Matthew AG et al (2012) Exercise in clinical cancer care: a call to action and program development description. Curr Oncol 19(3):e136–e144

Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, Courneya KS, Schmitz KH (2012) Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol 10(5):171–177

Irwin ML, Cartmel B, Gross C, Ercolano E, Fielin M et al (2015) Randomized controlled trial of exercise vs. usual care on aromatase-inhibitor associated arthralgias in women with breast cancer: the hormones and physical exercise (HOPE) study. J Clin Oncol 33

Galantino ML, Desai K, Greene L, Demichele A, Stricker CT, Mao JJ (2012) Impact of yoga on functional outcomes in breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias. Integr Cancer Ther 11(4):313–320

DeNysschen CA, Burton H, Ademuyiwa F, Levine E, Tetewsky S, O’Connor T (2014) Exercise intervention in breast cancer patients with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgia: a pilot study. Eur J Cancer Care 23(4):493–501

Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernandez-Lao C, Caro-Moran E, Morillas-Ruiz J, Galiano-Castillo N et al (2013) Aquatic exercise in a chest-high pool for hormone therapy-induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors: a pragmatic controlled trial. Clin Rehab 27(2):123–132

Galantino ML, Callens ML, Cardena GJ, Piela NL, Mao JJ (2013) Tai chi for well-being of breast cancer survivors with aromatase inhibitor-associated arthralgias: a feasibility study. Altern Ther Health Med 19(6):38–44

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study protocol was approved by the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee and the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Conflict of interest

This research is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21CA169492 and a pilot grant from the UNC Institute on Aging. The authors do not have a financial relationship with either organization. All authors have participated in writing, reviewing, and/or editing the manuscript. The principal investigator has full control of all primary data and agrees to allow the journal of Supportive Care in Cancer to review our data if requested. We thank the Arthritis Foundation, UNC Thurston Arthritis Research Center, and the North Carolina Cancer Hospital oncology physicians and clinical staff for their interest and support throughout the study, as well as the breast cancer survivors who participated in this study.

Additional information

Anne Wilson and Arielle Schechter are patient advisors to the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nyrop, K.A., Callahan, L.F., Rini, C. et al. Aromatase inhibitor associated arthralgia: the importance of oncology provider-patient communication about side effects and potential management through physical activity. Support Care Cancer 24, 2643–2650 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3065-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-3065-2