Abstract

Purpose

Patients with head and neck cancer experience multiple complaints during treatment which also affect quality of life. The present study assessed predictors of temporal changes in quality of life over a 6-month period among patients treated for head and neck cancer.

Methods

Patients completed questionnaires at the beginning (t1) and end (t2) of their hospital stay and 3 (t3) and 6 months (t4) thereafter. Quality of life was evaluated using EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-H&N35. Descriptive statistics were computed across measurement points for different domains of quality of life; predictors were identified using general linear models.

Results

Eighty-three patients (mean age: 58, SD = 11, 20.5% female) participated. Quality of life decreased during treatment and slowly recovered thereafter. From t1 to t4, there were adverse changes that patients consider to be relevant in physical and role functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, financial difficulties, problems with senses and teeth, limited mouth opening, mouth dryness, social eating, coughing, and sticky saliva. Temporal changes in global quality of life between t1 and t2 were predicted by tumor stage (B = − 5.6, p = 0.04) and well-being (B = 0.8, p = 0.04); radiotherapy was a predictor of temporal changes in physical functioning (B = − 12.5, p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Quality of life decreases during treatment, half a year after hospital stay there are still restrictions in some areas. A special focus should be given on head and neck cancer patient’s quality of life in the aftercare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality of life has emerged as an important treatment outcome for cancer patients. Accordingly, the number of research studies that have focused on the quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer has rapidly increased over the past few years. Numerous cross-sectional and prospective studies have shown that quality of life is extremely poor after a cancer diagnosis and continues to deteriorate during treatment [1,2,3]. Fortunately, most quality of life domains demonstrate improvement and some even return to baseline levels at one-year follow-up [4, 5]. Quality of life domains that are adversely affected for a longer duration include problems that affect the teeth, senses, sexuality, mouth (e.g., limited mouth opening, mouth dryness), and physical function [1, 5, 6]. Treatment factors significantly influence quality of life trajectories. Patients with feeding tube placement and those who have undergone radiotherapy are particularly impaired [5, 7]. In addition, the treatment for head and neck cancer is often accompanied by pain, eating, communication, and breathing problems, and occasional visual changes that can adversely affect quality of life [8, 9]. Further, social interactions can be limited by impaired communication, and emotional expression can be adversely affected depending on the tumor region. As a result, head and neck cancer patients have a high risk for perceived stigmatization, which can result in social withdrawal [10]. Further, the prevalence of depression is the highest among this group than among patients with other types of cancers [11].

Additionally, quality of life predicts the overall survival of patients with head and neck cancer [12, 13]. In particular, pre-treatment physical functioning is a strong predictor for survival [14]. Furthermore, changes in global quality of life scores from pre-treatment to posttreatment (6 months after treatment) are associated with the overall survival of patients with head and neck cancer [14]. Thus, it is necessary to assess quality of life across different time points because of their prognostic implications for survival [15].

Even though abundant data on the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients are available, only a few studies have examined longitudinal changes in different quality of life domains within this population. Although some studies have examined whether clinical and psychosocial variables and different types of treatments predict quality of life, very few studies have analyzed the predictors of longitudinal changes in quality of life. Additionally, statistically significant changes are not always equivalent to clinically relevant changes.

In the present study, we examined the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients across a 6-month period. The specific aims of the study were to (1) measure quality of life across four time points, (2) analyze improvements or deteriorations in different quality of life domains across the study period, and (3) identify the predictors of temporal changes in quality of life domains that cancer patients consider to be relevant.

Patients and methods

Design and data collection

In this prospective study, all the patients who had been admitted to the Departments of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology and Radio-Oncology at the University Hospital Leipzig between October 2012 and June 2014 for the treatment of head and neck cancer were eligible for inclusion in the study sample. The sample exclusion criteria were as follows: no histologically confirmed malignancy, no written informed consent, age < 18 years, and a lack of fluency in the German language. Study nurses contacted patients with primary as well as recurrent diseases shortly after admission and informed them about the nature, procedure, and aims of the study. After they had provided written informed consent, the patients were interviewed upon hospitalization (t1), at hospital discharge (t2), and 3 (t3), and 6 months after baseline (t4). At t1 and t2, data were collected electronically using the Computer-based Health Evaluation System (CHES) software [16]. At t3 and t4, the participants were telephonically contacted and interviewed. This study was granted ethical approval by the institutional review board of Leipzig University (#210-12-02072012).

Instruments

Quality of life was measured at baseline and all follow-ups using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and Head and Neck Module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35). These are self-report questionnaires that are used in clinical studies on cancer [17, 18]. In total, the EORTC QLQ-C30 consists of 30 items that can be summarized into 5 functional scales and 3 multi-item, and 6 single-item scales that assess cancer-related symptoms and global quality of life. The EORTC QLQ-H&N35 consists of 35 items, which constitute 7 multi-item and 11 single-item symptom scales. Responses are given on a four-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (”very much”), with the exceptions of (1) items that measure global quality of life for which the rating scale ranges from 1 (“very poor”) to 7 (“excellent”) and (2) 5 yes–no items (painkillers, nutritional supplements, feeding tube, weight loss, and weight gain). The measures were scaled from 0 to 100, whereby higher scores on the functional and global quality of life scales and lower scores on the symptom scales indicate better quality of life [19]. Overall, the reliability and validity of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-H&N35 have been found to be acceptable [20, 21].

Clinical data were ascertained from medical reports. Tumor stage was classified according to the Union for International Cancer Control [UICC] classification system seventh edition [22].

The participants provided information about their socio-demographic characteristics (age, gender, education) in response to structured questions. Educational level was defined as the highest educational qualification of the patient (none, apprenticeship, higher, university). This variable was consequently dichotomized as follows: low (none, apprenticeship) and high educational level (higher, university).

Emotional well-being was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [23]. This self-report instrument, which is suitable for use with nonpsychiatric samples, consists of 14 items, and the corresponding item scores can be summarized into a total score. A score that is greater than or equal to 13 is indicative of clinically relevant distress in a patient with cancer [24].

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s χ² and independent-samples t tests were used to compare participants and non-participants as well as dropouts and study completer. The scores of the functional and symptom scales were calculated in accordance with the guidelines of the EORTC [19]. Descriptive statistics, namely, means and standard deviations, were computed for quality of life. Temporal changes in quality of life were analyzed by examining absolute pairwise differences between different measurement time points. To identify the predictors of temporal changes in quality of life from t1 and t2, multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted. The dependent variables were the quality of life domains in which scores had changed by five or more points; patients consider this to be a minor change in quality of life [25]. Because not all participants completed the EORTC QLQ-H&N35, this analysis was undertaken only for the data that were collected using the EORTC QLQ-C30. The following independent variables were entered into all the regression models: age, tumor stage (I–IV), radiotherapy (yes, no), educational level (low, high), and well-being (continuous variable). Data analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS® Statistics Version 25.

Results

Sample characteristics

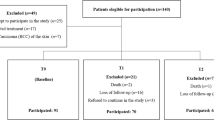

A total of 111 patients were admitted to the two aforementioned departments for treatment of head and neck cancer during the study period. Of those, 28 (25%) patients had declined to participate in the study (reasons: lack of interest n = 19, too distressed because of the disease n = 3, mentally distressed n = 3; 3 did not provide any reason). Baseline data were available for 81 patients, and 2 patients were included in the study after t1 because the interviewer had been notified at a later time. Sixty-five (78%) of the 83 study participants also participated at t2, but only 64 of them provided data about their quality of life. Further, 51 (61%) and 46 (55%) of them participated at t3 and t4, respectively. Participants had dropped out of the study for the following reasons: patient declined to continue to participate in the study (n = 13 (t2), 23 (t3), 27 (t4)), patient could not be contacted (n = 1, 3, 2), patient was not capable of being interviewed (n = 4, 2, 2), and patient was deceased (n = 0, 4, 6).

Participants and non-participants did not differ in age (p = 0.44), sex (p = 0.25), and tumor stage (p = 0.88). Patients who completed all the follow-up measurement across the different time points differed from dropouts and those who had missed a few interviews between t1 and t4 in age (Mdropout = 61.5 years, Mcompleter = 55.0 years; p = 0.01) but not in sex (p = 0.83), tumor stage (p = 0.44), educational level (p = 0.32), and well-being (p = 0.06) at t1 as well as radiotherapy status at t2 (p = 0.27). With regard to baseline levels of quality of life, patients who had completed the assessments across all the different time points differed from dropouts in only one variable, namely, dyspnea (Mcompleter = 12.8, Mdropout = 30.2; p = 0.05).

The ages of the participants ranged from 28 to 83 years (Mage = 58 years), and 20.5% of them were women. Most of the participants had primary cancers. A majority of the patients had tumor stage IV and had completed post-compulsory education (Table 1).

Temporal changes in quality of life

The means for the functional and symptom scale scores across the four measurement points are presented in Table 2. Because the EORTC QLQ-H&N35 was distributed only within the head and neck ward, patients who were treated in the radiation clinic did not complete this questionnaire. All domains except emotional functioning, dyspnea, and limited mouth opening had deteriorated between t1 and t2 (Table 3). Quality of life domains that had further declined by t3 were as follows: physical and social functioning, nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea, financial difficulties, sensory problems, sexuality, problems with teeth, limited mouth opening, mouth dryness, coughing, and feeling ill. Emotional functioning and dyspnea had worsened between t2 and t3 even though they had improved between t1 and t2. Between t3 and t4, the following quality of life domains had worsened: physical, emotional, and cognitive functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, constipation, diarrhea, financial difficulties, limited mouth opening, mouth dryness, and feeding tube status. Quality of life domains with adverse changes between t1 and t4 that patients consider to be relevant [25, 26] were as follows: physical and role functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, financial difficulties, problems with senses and teeth, limited mouth opening, mouth dryness, social eating, coughing, and sticky saliva.

Predictors of temporal changes in quality of life

To identify the predictors of temporal changes in quality of life between t1 and t2, we calculated exploratory linear models for quality of life domains with change scores between t1 and t2 that were > 5 points as dependent variables. Since the independent variables contained missing data, the analyses were conducted using a sample of 60 patients. We found that global quality of life had deteriorated among patients with higher tumor stages (B = − 5.6, p = 0.04) and improved among patients with poor emotional well-being (B = 0.8, p = 0.04) at t1. Physical functioning had worsened among patients who had received radiotherapy (B = − 12.5, p = 0.03) at t2 (Table 4). The independent variables did not predict temporal changes in role functioning, fatigue, pain, loss of appetite, and insomnia. Changes in functional and symptom scale scores were not associated with educational level.

Discussion

The present study investigated temporal changes in quality of life among head and neck cancer patients up to 6 months after hospitalization. Consequently, the findings offer insights into the quality of life domains that improve or worsen during this time period. Furthermore, we identified the predictors of temporal changes in quality of life between t1 and t2 that patients consider to be relevant.

Temporal changes in quality of life

Consistent with the findings of past studies that have been conducted among head and neck cancer patients, our results show that almost all the quality of life domains had deteriorated during cancer treatment and slowly improved thereafter [1, 3]. Whereas some domains had returned to baseline levels within half a year (e.g., pain, speech problems), some remained problematic. Mouth dryness was the quality of life domain that demonstrated the most evident changes. Patients reported an average increase of 34.6 points for this symptom; this is indicative of a substantial temporal change in this quality of life domain [25]. Other studies have also shown that mouth dryness is the quality of life domain that demonstrates the greatest deterioration across time [1, 27]. Radiotherapy, which is a common treatment modality for head and neck cancer, has several side effects, of which mouth dryness is one of the most common. This occurs as a result of the irritation of the salivary glands [28]. The second largest change was found to be an increase in financial difficulties. Similar results were found in other studies that were conducted among patients with head and neck cancer and partial and total laryngectomy [4, 29, 30]. A possible explanation for this finding is that patients with head and neck cancer have very little or no financial savings because this cancer is more common among low income individuals [31]. Financial burden is mostly attributable to fuel costs, food preparation at home, dietary changes, and a loss of earnings [32]. Also other problems seem to be more pronounced among patients with a low socioeconomic status [33]. Patients also reported relevant changes in physical functioning. This is consistent with past findings that physical functioning remains impaired even after 3 years after diagnosis [1, 5, 34]. This may be attributable to the side effects of the treatment; for example, shoulder disability, neck pain, and reduced cervical mobility are reported by patients after they receive cancer treatment [35, 36].

Predictors of temporal changes in quality of life

Another aim of this study was to identify the predictors of changes in quality of life between t1 and t2. We found that radiotherapy status was a significant predictor of changes in physical functioning. As mentioned earlier, the side effects of cancer treatments strongly influence the physical functioning of patients with head and neck cancer. In particular, loss of sensation and neck pain have been reported by patients who have been undergone radiotherapy [35, 37]. In our study, tumor stage predicted changes in global quality of life. This can be contrasted against other findings that cancer stage has no effect on quality of life a year after treatment [5, 38]. In our study, quality of life was assessed both before and after hospitalization; therefore, the stage of the disease may be highly correlated with the reception of treatment and may consequently overlap with side effects. Finally, distress predicted global quality of life in this study. Contrary to past findings, higher levels of distress at t1 were associated with positive changes in quality of life between t1 and t2 in our study [5]. This may be attributable to the fact that patients who are highly distressed at the beginning of their hospital stay adjust to their cancer diagnosis, whereas those with low levels of distress realize the adverse consequences of their disease only at a later time. Of the 22 patients who were classified as “distressed” at t1 (HADS ≥ 13 points) [39], 7 (32%) of them were not distressed at t2. Further, global quality of life was negatively related to distress at both t1 and t2. Educational level was not associated with changes in quality of life.

Fortunately, patients also demonstrated improvements in some quality of life domains. Emotional functioning had increased by four points between baseline and t4. This change may be attributable to chance or adaptive coping. Improvements in mental well-being after a cancer diagnosis were also found in another study [34].

Limitations

The present study has a few methodological limitations that need to be considered when the results of this study are interpreted. Since the participants of the present study were the control group of another intervention study, data could be collected only until 6 months after baseline. Further, the sample size was small; as a result, other potential prognostic variables were not entered into the regression models. The sizes of the subgroups that varied in tumor sites were small; therefore, tumor site, which is an otherwise important variable, was not examined as a predictor [40, 41]. As a result of the heterogeneity of the study population, the results may not be generalizable to all corresponding subgroups and may differ between patients with different tumor sites. Furthermore, 43% of the participants had dropped out by t4. Although dropouts and those who completed all the follow-up assessments differed only in age, the present results may be biased. Finally, we did not collect data about the type of radiotherapy that the patients had received, and this may have had an impact on their quality of life. Despite these limitations, the present findings offer insights into the variables that predict changes in quality of life domains that demonstrate a decrease of five or more points between the beginning and end of hospital stay.

Conclusions

In sum, we found that almost all quality of life domains had deteriorated during hospital stay and had slowly recovered half a year later. Nevertheless, there are some domains with adverse changes between t1 and t4 that patients consider to be relevant: physical and role functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, financial difficulties, problems with senses and teeth, limited mouth opening, mouth dryness, social eating, coughing, and sticky saliva. Because quality of life is a prognostic factor that influences the survival of head and neck cancer patients, data should be routinely collected as a part of aftercare. Further, financial problems should be assessed and discussed during follow-up consultations because this seems to be a relevant issue that confronts head and neck cancer patients. Early inclusion of social workers in cancer treatment can facilitate the provision of information about financial support to patients. Future researchers must replicate this research study using a larger sample. We also encourage future researchers to examine subgroup differences and compare the quality of life of patients with different tumor sites. Additionally, it may be beneficial to conduct qualitative studies to assess the main reasons that underlie the financial difficulties that are faced by this group so that targeted information can be provided to them.

References

Hammerlid E, Silander E, Hörnestam L et al (2001) Health-related quality of life three years after diagnosis of head and neck cancer-a longitudinal study. Head Neck 23(2):113–125

Hammerlid E, Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M et al (1997) Prospective, longitudinal quality-of-life study of patients with head and neck cancer: a feasibility study including the EORTC QLQ-C30. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 116(6 Pt 1):666–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-59989770246-8

Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Hammerlid E et al (2001) A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part II: longitudinal data. Laryngoscope 111(8):1440–1452. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200104000-00021

Clasen D, Keszte J, Dietz A et al (2018) Quality of life during the first year after partial laryngectomy: longitudinal study. Head Neck 40(6):1185–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25095

Ronis DL, Duffy SA, Fowler KE et al (2008) Changes in quality of life over 1 year in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 134(3):241–248. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2007.43

Abendstein H, Nordgren M, Boysen M et al (2005) Quality of life and head and neck cancer: a 5 year prospective study. Laryngoscope 115(12):2183–2192. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLG.0000181507.69620.14

Schultz C, Goffi-Gomez MVS, Pecora Liberman PH et al (2010) Hearing loss and complaint in patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136(11):1065–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2010.180

Macfarlane TV, Wirth T, Ranasinghe S et al (2012) Head and neck cancer pain: systematic review of prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Maxillofac Res 3(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.5037/jomr.2012.3101

Larsson M, Hedelin B, Johansson I et al (2005) Eating problems and weight loss for patients with head and neck cancer: a chart review from diagnosis until one year after treatment. Cancer Nurs 28(6):425–435

Danker H, Wollbrück D, Singer S et al (2010) Social withdrawal after laryngectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267(4):593–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-009-1087-4

Massie MJ (2004) Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. https://doi.org/10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh014

Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ronis DL, Fowler KE et al (2008) Quality of life scores predict survival among patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 26(16):2754–2760. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9510

Meyer F, Fortin A, Gélinas M et al (2009) Health-related quality of life as a survival predictor for patients with localized head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 27(18):2970–2976. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0295

van Nieuwenhuizen AJ, Buffart LM, Brug J et al (2015) The association between health related quality of life and survival in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oral Oncol 51(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.002

Meyer F, Fortin A, Gélinas M et al (2009) Health-related quality of life as a survival predictor for patients with localized head and neck cancer treated with radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 27(18):2970–2976. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0295

Holzner B, Giesinger JM, Pinggera J et al (2012) The Computer-based Health Evaluation Software (CHES): a software for electronic patient-reported outcome monitoring. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 12:126. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-12-126

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B et al (1993) The european organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 85(5):365–376. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

Bjordal K, Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmqvist M et al (1999) Quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: validation of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-H&N35. J Clin Oncol 17(3):1008–1019. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1008

Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group (2001) The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual, 3rd edn. EORTC, Brüssel

Bjordal K, Kaasa S (1992) Psychometric validation of the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire, 30-item version and a diagnosis-specific module for head and neck cancer patients. Acta Oncol 31(3):311–321

Singer S, Arraras JI, Chie W-C et al (2013) Performance of the EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients EORTC QLQ-H&N35: a methodological review. Qual Life Res 22(8):1927–1941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0325-1

Sobin Leslie H, Gospodarowicz Mary K, Wittekind Christian (2011) TNM classification of malignant tumours, 7. Wiley, New York

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

Singer S, Kuhnt S, Götze H et al (2009) Hospital anxiety and depression scale cutoff scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer 100(6):908–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604952

Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J et al (1998) Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 16(1):139–144. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139

King MT (1996) The interpretation of scores from the EORTC quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res 5(6):555–567

Epstein JB, Emerton S, Kolbinson DA et al (1999) Quality of life and oral function following radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Head Neck 21(1):1–11

Valdez IH (1991) Radiation-induced salivary dysfunction: clinical course and significance. Spec Care Dentist 11(6):252–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-4505.1991.tb01490.x

Singer S, Danker H, Guntinas-Lichius O et al (2014) Quality of life before and after total laryngectomy: results of a multicenter prospective cohort study. Head Neck 36(3):359–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.23305

Rogers SN, Harvey-Woodworth CN, Lowe D (2012) Patients’ perspective of financial benefits following head and neck cancer in Merseyside and Cheshire. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 50(5):404–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.07.020

Johnson S, McDonald JT, Corsten MJ (2008) Socioeconomic factors in head and neck cancer. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 37(4):597–601

Rogers SN, Harvey-Woodworth CN, Hare J et al (2012) Patients’ perception of the financial impact of head and neck cancer and the relationship to health related quality of life. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 50(5):410–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.07.026

Tribius S, Meyer MS, Pflug C et al (2018) Sozioökonomischer Status und Lebensqualität bei Patienten mit lokal fortgeschrittenen Kopf-Hals-Tumoren (Socioeconomic status and quality of life in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer). Strahlenther Onkol 194(8):737–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00066-018-1305-3

de Graeff A, de Leeuw JR, Ros WJ et al (2000) Long-term quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope 110(1):98–106. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200001000-00018

van Wilgen CP, Dijkstra PU, van der Laan Berend F A M et al (2004) Morbidity of the neck after head and neck cancer therapy. Head Neck 26(9):785–791. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20008

Cappiello J, Piazza C, Nicolai P (2007) The spinal accessory nerve in head and neck surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 15(2):107–111. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e3280523ac5

Schuller DE, Reiches NA, Hamaker RC et al (1983) Analysis of disability resulting from treatment including radical neck dissection or modified neck dissection. Head Neck Surg 6(1):551–558

Hammerlid E, Taft C (2001) Health-related quality of life in long-term head and neck cancer survivors: a comparison with general population norms. Br J Cancer 84(2):149–156. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.2000.1576

Singer S, Kuhnt S, Götze H et al (2009) Hospital anxiety and depression scale cutoff scores for cancer patients in acute care. Br J Cancer 100(6):908–912. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604952

Veldhuis D, Probst G, Marek A et al (2016) Tumor site and disease stage as predictors of quality of life in head and neck cancer: a prospective study on patients treated with surgery or combined therapy with surgery and radiotherapy or radiochemotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 273(1):215–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-015-3496-x

Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE et al (2004) Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130(4):401–408. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.130.4.401

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SS received a grant from Pfizer, honoraria from Lilly, and lecture fees from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Boehringer Ingelheim; all were outside of this study. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed within this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roick, J., Danker, H., Dietz, A. et al. Predictors of changes in quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: a prospective study over a 6-month period. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277, 559–567 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05695-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05695-z