Abstract

Purpose

The effectiveness of laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy (Laparoscopic-KPE) for biliary atresia (BA) has been reported but remains controversial. We reviewed our own cases and cases described in previous studies of liver transplantation (LT) for BA after Laparoscopic-KPE to investigate the efficacy of Laparoscopic-KPE.

Methods

Subjects were children of ≤ 2 years old with LT for BA after KPE who underwent Laparoscopic-KPE (n = 10) or Open-KPE (n = 115) between 2009 and 2020. Propensity score matching was performed to reduce the effect of treatment selection bias. The clinical data regarding the preoperative characteristics and surgical results were compared.

Results

The rates of hypoplastic portal vein and retrograde portal vein flow were lower in the Laparoscopic-KPE group than in the Open-KPE group (0 vs. 40.0%, p = 0.02 and 0 vs. 35.0%, p = 0.04). There was no marked difference in the operation time or duration of hepatectomy. For portal vein reconstruction, a vein graft was not required in the Laparoscopic-KPE group (0 vs. 35.0%, p = 0.03). No patients in the Laparoscopic-KPE group developed portal vein complications or required re-laparotomy for bowel perforation or re-bleeding, in contrast to the Open-KPE group (0 vs. 15.0% and 0 vs. 10.0%, respectively).

Conclusion

Laparoscopic-KPE may reduce postoperative complications that necessitate re-laparotomy in LT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

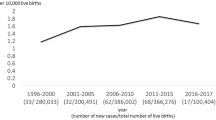

Biliary atresia (BA) is a progressive disease of the hepatobiliary system, and Kasai portoenterostomy (KPE) has been established as an initial radical operation [1]. Even though KPE may temporarily improve jaundice, 41.1% of patients ultimately undergo liver transplantation (LT) in Japan [2]. In recent years, the results of LT for BA have been improving, with a 1-year survival rate of 90.5% and 10-year survival rate of 84.6%, thanks to improvements in surgical techniques, anesthesia management and perioperative management [3]. However, there is room for further improvement in pediatric LT for BA, as there are still some cases in which portal vein reconstruction is difficult, which may lead to graft loss and death.

The surgical technique and frequency of KPE may also be a major factor that can affect the outcomes of LT. Previous studies reported that a history of multiple surgical operations before LT was a surgical risk factor for postoperative bowel perforation or vascular complications in subsequent LT [4, 5].

Laparoscopic-KPE was first performed by Esteves [6], who reported that it was associated with various advantages over open surgery, including a fast recovery, prompt oral feeding, less pain and a reduction in postoperative adhesion, and that it facilitated subsequent LT [7]. Although minimally invasive surgery has become the main operation in the field of pediatric surgery, Laparoscopic-KPE has not yet been established as a widely used technique because of the technical difficulty, and many studies have reported that the improvement of jaundice after Laparoscopic-KPE was inferior to that with Open-KPE [8,9,10]. A previous report indicated that the 10-year native liver survival rate after Laparoscopic-KPE was 45.5% (5/11), while that after, Open-KPE was 85.0% (17/20) (p = 0.03), indicating that Open-KPE is still the treatment of choice for BA [9]. However, several recent studies have reported that the results of Laparoscopic-KPE were comparable to those of Open-KPE, mainly in Asia [11,12,13]. One study reported that the duration of hepatectomy in LT in patients ≤ 2 years old who underwent Laparoscopic-KPE was significantly shorter than that following Open-KPE due to less adhesion [14]. However, the assessment of the degree of intra-abdominal adhesion is difficult and—in the clinical setting—is mostly based on subjective descriptions [15].

Considering the impact of intra-abdominal adhesion on the postoperative complications in LT, as described above [4, 5], it was hypothesized that the detailed verification of surgical complications in LT would be effective for assessing the efficacy of Laparoscopic-KPE.

We herein reviewed the cases that we have experienced as well as the cases reported in previous studies of LT for BA after Laparoscopic-KPE and investigated the surgical complications to evaluate the efficacy of Laparoscopic-KPE.

Methods

Our cases

Patients with BA after Laparoscopic-KPE were referred to our institute for LT starting in 2009. Between 2009 and 2020, 190 consecutive living donor LTs (LDLTs) for BA after KPE were performed at our hospital for children of ≤ 2 years old. LDLT was performed by a single team of skilled transplant surgeons comprising M.K, S.S and A.F. Ten patients (5.3%) underwent Laparoscopic-KPE before LT. Seven patients were referred from two major pediatric surgery departments in Japan (Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine and Juntendo University School of Medicine) that actively performed Laparoscopic-KPE. Recent studies reported that the outcomes of Laparoscopic-KPE performed in these 2 departments were excellent and comparable to the outcomes of Open-KPE (jaundice-free native liver survival at 2 years: Open-KPE 63.0 and 71.4% vs. Laparoscopic-KPE: 70.4 and 73.7% [14, 16, 17]).

Among 180 patients who underwent Open-KPE, we excluded those who underwent multiple laparotomy procedures, such as small bowel obstruction or redo-KPE. The preoperative characteristics and surgical results were analyzed in the Laparoscopic-KPE (n = 10) and Open-KPE (n = 115) groups. Furthermore, results were compared between the Laparoscopic-KPE and propensity-matched Open-KPE (n = 20) groups.

The preoperative characteristics, postoperative complications, length of hospital stay and patient/graft survival rate were analyzed. Postoperative re-laparotomy was defined as an operation for bowel perforation, intraperitoneal drainage or re-bleeding within one month after LT. We also examined the rate of hypoplastic portal vein and retrograde portal vein flow before LT as risk factors for portal vein reconstruction [18]. A hypoplastic portal vein was defined by a diameter of < 4.0 mm on preoperative Doppler ultrasonography [18].

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the National Center for Child Health and Development (Institutional review board number: NCCHD #404).

Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria

For our review of the relevant literature, we searched all publications from 2002 to 2020 using MEDLINE with the following search terms: (biliary atresia) AND (laparoscopic portoenterostomy OR laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy) AND (liver transplantation). The bibliographies of potentially relevant articles were also manually searched to identify additional eligible studies. After identifying the relevant titles and abstracts, the studies were assessed independently by the authors for inclusion in the literature review. All studies describing the assessment of adhesion in LT or complications in LT were included. Studies that only included the number of LT operations were excluded.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis of the difference between the Laparoscopic-KPE and Open-KPE groups was performed, as appropriate, using the chi-square test, the Mann–Whitney U test, a Kaplan–Meier analysis, or the propensity score model using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [19], and a modified version of R commander. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

For propensity score matching, we mainly selected items that would affect the outcome of LT, such as the age at LT, body weight at LT, ascites, pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) score, donor age, ABO blood type incompatibility and graft-to-recipient weight ratio. To match the background, we also selected the gender ratio, age at KPE and incidence of cholangitis. After estimating the propensity scores, 1:2 nearest neighbor matching was performed.

Results

Our cases

After 1:2 propensity score matching, all patients in the Laparoscopic-KPE group were matched to similar patients in the Open-KPE group (Table 1). The rates of hypoplastic portal vein and retrograde portal vein flow were significantly lower in the Laparoscopic-KPE group than in the Open-KPE group (Laparoscopic-KPE vs. Open-KPE: 0 vs. 40.0%, p = 0.02; and 0 vs. 35.0%, respectively, p = 0.03).

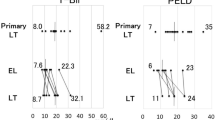

There were no significant differences between the two groups in operation time for LDLT, duration to the completion of hepatectomy or intraoperative bleeding (Table 2). Regarding intraoperative findings, 10.0% (2/20) of the patients in the Open-KPE group required additional bowel resection (Laparoscopic-KPE group: 0%, p = 0.30). For portal vein reconstruction, a vein graft was required in 35.0% (7/20) of the cases in the Open-KPE group (Laparoscopic-KPE group: 0%, p = 0.03). Regarding complications, portal vein thrombosis or portal vein stenosis was observed in 15.0% (3/20) of the patients in the Open-KPE group, but no portal vein thrombosis or portal vein stenosis was seen in the Laparoscopic-KPE group. In addition, in the Open-KPE group, the rate of re-laparotomy due to bowel perforation or intraperitoneal drainage was 10.0% (2/20), while re-laparotomy was not required in the Laparoscopic-KPE group. One case of bile leak in the Laparoscopic-KPE group improved with conservative treatment.

The 1-year graft and patient survival rates were almost the same between the groups (Laparoscopic-KPE vs. Open-KPE: 100 vs. 88.8%, p = 0.98 and 100% vs. 94.4%, p = 0.98, respectively). One patient who underwent re-transplantation for portal vein stenosis died due to worsening of respiratory failure with intrapulmonary shunt; the other died 1.5 months after transplantation due to graft dysfunction caused by portal vein thrombosis.

Review of the literature

Our search of the relevant literature revealed 66 reports. Among these, 15 described LT after Laparoscopic-KPE, and 5 further verified the findings of adhesion or complications in LT. These five reports were included in the present study [7, 14, 15, 20, 21].

Three of the five reports assessed adhesion subjectively, based on the opinion of the transplant surgeon (Table 3) [7, 20, 21]. Two reports concluded that Laparoscopic-KPE could more effectively reduce postoperative adhesion than Open-KPE [7, 21]. Another report indicated that a minimal access approach did not result in a reduction in peri-hepatic adhesion formation because three of five cases after Laparoscopic-KPE had mild to dense adhesion [20]. Two papers evaluated adhesion during LT based on hepatectomy time, total operating time or blood loss [14, 15]. One paper showed that the hepatectomy time was significantly shorter in the Laparoscopic-KPE group than in the Open-KPE group and that the Laparoscopic-KPE group had a shorter hospital stay, indicating the superiority of Laparoscopic-KPE over Open-KPE [14]. The other paper concluded that there was no marked difference in the operating time, hepatectomy time or blood transfusion volume. The authors also noted that, throughout the entire abdomen, adhesion was likely to be mild after Laparoscopic-KPE, but the two treatment groups showed a similar degree of scarring in the portal area [15].

Complications were described in 2 reports, 1 of which described the necessity of postoperative re-laparotomy due to insufficient anastomosis in 2 of 8 cases (25.0%) in the Laparoscopic-KPE group. However, in that study, 4 of the 11 cases (36.4%) in the Open-KPE group required re-laparotomy for the same reason. Furthermore, no cases required re-laparotomy due to bowel perforation or re-bleeding [15]. The other study only mentioned intraoperative complications and stated that none of the eight cases in the Laparoscopic-KPE group developed complications, including portal vein thrombosis [14].

Discussion

In the present study, which examined the complications in LT after Laparoscopic-KPE in detail, no patients in the Laparoscopic-KPE group required surgical treatment after LT due to postoperative bowel perforation or intra-abdominal re-bleeding. Furthermore, no patients in the Laparoscopic-KPE group developed portal vein complications, and there were no cases in which vein graft interposition was used for reconstruction of the portal vein. The results regarding the absence of portal vein thrombosis, postoperative bowel perforation and re-bleeding were in line with the previous studies that we reviewed.

We investigated the effects of Laparoscopic-KPE by examining the complications of LT. Our review of the literature revealed that the influence of adhesion after Laparoscopic-KPE was evaluated based on the subjective judgment of the transplant surgeon or the time required for hepatectomy in LT. Regarding the time for hepatectomy, two previous reports showed different results [14, 15]. Our survey did not find any marked difference between the two groups in the time required for hepatectomy. This was highly case-specific and indicated that the time required for hepatectomy did not differ notably between the two groups. We considered that examining complications in LT was more clinically meaningful than the time required for hepatectomy when assessing adhesion after Laparoscopic-KPE, as previous reports showed that adhesion after repeat KPE was associated with high rates of bowel perforation or vascular complications, which represent lethal postoperative complications after LT [4, 5].

The incidence of bowel perforation after pediatric LT was reported to be 6.4–20.0% [22]. In the Laparoscopic-KPE group, none of the patients required intraoperative additional bowel resection after adhesiolysis (Laparoscopic-KPE vs. Open-KPE: 0% vs. 10.0%), and none required re-laparotomy for postoperative bowel perforation or re-bleeding (Laparoscopic-KPE vs. Open-KPE 0 vs. 10.0%). A previous study reported the same results [15]. In general, most patients with additional bowel resection, intraperitoneal re-bleeding or postoperative bowel perforation have strong intraperitoneal adhesion in LT (Fig. 1). Thus, the absence of such bowel resection or complications in the Laparoscopic-KPE group is one possible reason for mild postoperative adhesion after Laparoscopic-KPE (Fig. 2). Intraperitoneal re-bleeding or postoperative bowel perforation can be fatal in LT; thus, the low risk of these complications may be an advantage of Laparoscopic-KPE.

The present study suggested that Laparoscopic-KPE may associated with a reduction in portal vein complications in patients undergoing LDLT. The rates of hypoplastic portal vein, retrograde portal vein flow and using vein graft interposition for portal vein reconstruction were significantly lower in the Laparoscopic-KPE group than in the Open-KPE group (0 vs. 40.0%, p = 0.02, 0 vs. 35.0%, p = 0.03, and 0 vs. 35.0%, p = 0.03, respectively). These significant differences indicate that the risk of portal vein complications was lower in the Laparoscopic-KPE group than in the Open-KPE group.

Furthermore, just as two deaths in the Open-KPE group were actually associated with portal vein complications, portal vein complications are a very important issue in LT that directly affects the graft function and patient survival. In our previous report, the rate of portal vein complications was 8.6%, and an interposition graft was used for reconstruction of the portal vein in 28.4% of cases [23]. However, in 10 cases in our Laparoscopic-KPE group and 8 cases described in previous reports [14], there were no intraoperative portal vein complications. This may be related to minimal invasion around the portal vein in Laparoscopic-KPE compared with Open-KPE (Fig. 3). In KPE, conservative dissection around the portal vein may reduce invasion of the portal vein. Sugawara et al. reported that severe intra-abdominal adhesion could cause frequent vascular complications due to difficulty dissecting the porta hepatitis in LT [4]. Furthermore, previous reports indicated that Laparoscopic-KPE was associated with significantly less intraoperative bleeding than Open-KPE as a result of its minimal invasiveness [11, 14]. Delicate surgery using a magnified field of view with a laparoscope [6] may be a major factor in reducing surgical invasion to the porta hepatitis in Laparoscopic-KPE. In contrast, invasion of the portal vein is thought to be affected by not only KPE but also cholangitis after KPE. Portal vein complications are highly related to the outcomes of LT for BA. Taken together, future studies including a histopathological evaluation of the portal vein wall should be performed to examine whether or not Laparoscopic-KPE is actually associated with portal vein complications.

Intraoperative findings of Open-KPE and Laparoscopic-KPE. In Open-KPE, the hepatic artery (black arrows) and portal vein (white arrows) are exposed well after dissection of the porta hepatitis (A). In contrast, in Laparoscopic-KPE, it is possible to dissect just around the biliary remnant (open arrowheads) with a delicate procedure (B). There is still one layer above most of the hepatic artery and portal vein after dissection of the porta hepatitis and biliary remnant, and the portal vein may be less markedly invaded. KPE Kasai portoenterostomy, HA hepatic artery, PV portal vein

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention, including its retrospective design, the limited number of patients in the Laparoscopic-KPE group and the fact that multiple factors were involved in the outcomes of LDLT. Due to its retrospective design, we were unable to investigate the possibility of a causal relationship between Laparoscopic-KPE and the outcomes of LDLT. However, our findings did suggest many other implications, as described above. In the future, the further accumulation of data, an increase in the number of Laparoscopic-KPE cases and the performance of prospective studies will allow us to verify in greater detail whether or not there is a statistically significant difference in the rate of re-laparotomy and postoperative complications between Open-KPE and Laparoscopic-KPE groups. Furthermore, our main goal in KPE is to improve the jaundice-free native liver survival, not to reduce the complication rate of LT. However, as noted above, the institutions that performed Laparoscopic-KPE in this study showed no marked difference in the native liver survival rate between Open-KPE and Laparoscopic-KPE [14, 16, 17]. We believe that it is worthwhile to examine the impact of KPE on LT in such a group of patients.

Since complications in LT are associated with many factors, we were unable to conclude that Laparoscopic-KPE clearly reduces the rate of complications in this study. However, a review of our own cases and previous cases suggested that the complication rate in LT after Laparoscopic-KPE might be low. In an era when a certain percentage of patients with BA require LT, it may be worthwhile to verify whether or not Laparoscopic-KPE is a factor related to complications in LT.

In addition to being the first report to demonstrate the possible usefulness of Laparoscopic-KPE from the viewpoint of post-transplant complications, this study also highlights the need for future collaboration between pediatric and transplant surgeons.

References

Kasai M, Suzuki S (1959) A new operation for non-correctable biliary atresia: hepatic portoenterostomy. Shujutu 13:733

Japanese biliary atresia society (2019) Japanese biliary atresia registry in 2017. J Jpn Soc Pediatr Surg 55:291–297

Kasahara M, Umeshita K, Sakamoto S, Fukuda A, Furukawa H, Sakisaka S et al (2018) Living donor liver transplantation for biliary atresia: An analysis of 2085 cases in the registry of the Japanese Liver Transplantation Society. Am J Transplant 18:659–668

Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Kaneko J, Ohkubo T, Mizuta K, Kawarasaki H (2004) Impact of previous multiple portoenterostomies on living donor liver transplantation for biliary atresia. Hepatogastroenterology 51:192–194

Urahashi T, Ihara Y, Sanada Y, Wakiya T, Yamada N, Okada N et al (2013) Effect of repeat Kasai hepatic portoenterostomy on pediatric live-donor liver graft for biliary atresia. Exp Clin Transplant 11:259–263

Esteves E, Clemente Neto E, Ottaiano Neto M, Devanir J, Esteves Pereira R (2002) Laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 18:737–740

Martinez-Ferro M, Esteves E, Laje P (2005) Laparoscopic treatment of biliary atresia and choledochal cyst. Semin Pediatr Surg 14:206–215

Ure BM, Kuebler JF, Schukfeh N, Engelmann C, Dingemann J, Petersen C (2011) Survival with the native liver after laparoscopic versus conventional kasai portoenterostomy in infants with biliary atresia: a prospective trial. Ann Surg 253:826–830

Chan KWE, Lee KH, Wong HYV, Tsui SYB, Mou JWC, Tam YHP (2019) Ten-year native liver survival rate after laparoscopic and open kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 29:121–125

Hussain MH, Alizai N, Patel B (2017) Outcomes of laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: a systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 52:264–267

Murase N, Hinoki A, Shirota C, Tomita H, Shimojima N, Sasaki H et al (2019) Multicenter, retrospective, comparative study of laparoscopic and open Kasai portoenterostomy in children with biliary atresia from Japanese high-volume centers. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 26:43–50

Li Y, Gan J, Wang C, Xu Z, Zhao Y, Ji Y (2019) Comparison of laparoscopic portoenterostomy and open portoenterostomy for the treatment of biliary atresia. Surg Endosc 33:3143–3152

Li Y, Xiang B, Wu Y, Wang C, Wang Q, Zhao Y et al (2018) Medium-term outcome of laparoscopic kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia with 49 Cases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 66:857–860

Shirota C, Murase N, Tanaka Y, Ogura Y, Nakatochi M, Kamei H et al (2020) Laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy is advantageous over open Kasai portoenterostomy in subsequent liver transplantation. Surg Endosc 34:3375–3381

Oetzmann von Sochaczewski C, Petersen C, Ure BM, Osthaus A, Schubert KP, Becker T et al (2012) Laparoscopic versus conventional Kasai portoenterostomy does not facilitate subsequent liver transplantation in infants with biliary atresia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 22:408–411

Cazares J, Koga H, Murakami H, Nakamura H, Lane G, Yamataka A (2017) Laparoscopic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: single-center experience and review of literatures. Pediatr Surg Int 33:1341–1354

Nakamura H, Koga H, Cazares J, Okazaki T, Lane GJ, Miyano G et al (2016) Comprehensive assessment of prognosis after laparoscopic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 32:109–112

Kanazawa H, Sakamoto S, Fukuda A, Shigeta T, Loh DL, Kakiuchi T et al (2012) Portal vein reconstruction in pediatric living donor liver transplantation for patients younger than 1 year with biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg 47:523–527

Kanda Y (2013) Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48:452–458

Dutta S, Woo R, Albanese CT (2007) Minimal access portoenterostomy: advantages and disadvantages of standard laparoscopic and robotic techniques. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 17:258–264

Wada M, Nakamura H, Koga H, Miyano G, Lane GJ, Okazaki T et al (2014) Experience of treating biliary atresia with three types of portoenterostomy at a single institution: extended, modified Kasai, and laparoscopic modified Kasai. Pediatr Surg Int 30:863–870

Yanagi Y, Matsuura T, Hayashida M, Takahashi Y, Yoshimaru K, Esumi G et al (2017) Bowel perforation after liver transplantation for biliary atresia: a retrospective study of care in the transition from children to adulthood. Pediatr Surg Int 33:155–163

Sakamoto S, Uchida H, Kitajima T, Shimizu S, Yoshimura S, Takeda M et al (2020) The outcomes of portal vein reconstruction with vein graft interposition in pediatric liver transplantation for small children with biliary atresia. Transplantation 104:90–96

Acknowledgements

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT designed the study and wrote the draft of the manuscript, SS helped design the study and critically revised the article for clinical content, HU, SS, YY, AF, HU, AY collected the data, MK contributed to the study design and critical revision of the article for clinical content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Takeda, M., Sakamoto, S., Uchida, H. et al. Comparative study of open and laparoscopic Kasai portoenterostomy in children undergoing living donor liver transplantation for biliary atresia. Pediatr Surg Int 37, 1683–1691 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-04994-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-021-04994-z