Abstract

Meningiomas are rare in the pediatric age group, more so in the intraventricular location. They arise in the lateral ventricles from the arachnoid cells contained within the choroid plexus, in the third ventricle from the velum interpositum and in the fourth ventricle from the choroids. These tumors are usually large and have an aggressive behaviour. Surgical management of intra-ventricular meningiomas is challenging because of their deep location, large size at presentation and increased vascularity. The authors report two such cases who presented with symptoms of raised intra cranial pressure and on evaluation were found to have associated hydrocephalus. Both these patients underwent surgical excision of the tumour by frontal transcortical approach and histopathology report confirmed transitional meningioma in them. Only twenty seven cases of intraventricular meningiomas in children have been reported till date. Their definitive treatment is surgery alone and total excision of the tumor is curative. Possibility of neurofibromatosis as a differential should also be considered in their management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Case presentation

-

Case 1—

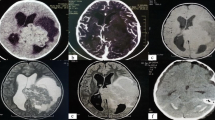

A 12-year-old boy presented to the department of neurosurgery with headache and vomiting for 4 months and recent onset of giddiness since 2 months. On examination, the child did not have any motor or sensory deficit. Fundus examination showed papilledema in both the eyes. The computed tomography (CT) brain revealed a large nodular, hyperdense, uniformly enhancing lesion occupying both the lateral ventricles (right more than left) and third ventricle with resultant ventricular dilatation (Fig. 1). On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion appeared isointense on T1, mildly hypointense on T2 (Fig. 2), and showed uniform enhancement on contrast administration (Fig. 3). This appeared to be primarily intraventricular arising from the right lateral ventricle and then involving the third as well as the left lateral ventricle. In view of the nodularity, the child was taken up for an endoscopic biopsy of the lesion. The lesion appeared fibrous and biopsy did not reveal any malignancy. CSF was also negative for abnormal cells and tumor markers. Three days later, the child underwent surgical excision. A bicoronal scalp flap was raised and a right frontal craniotomy was performed. A transcortical approach through the middle frontal gyrus was used and gross total excision of the lesion was achieved. The tumor was moderately vascular and of variable consistency being soft in the center and firm on the outer side of all nodules (Fig. 4). The tumor could be dissected easily from the ventricular wall as well as from its attachment to the tela choroidea. Frozen section confirmed a meningioma encouraging complete excision. Postoperative CT scan showed complete excision (Fig. 5). Transitional type of meningioma was further confirmed on histopathology evaluation with a MIB Index of 2%. Postoperative period was uneventful except for a small subdural collection which settled after two tappings.

-

Case 2—

A 3-year-old boy presented with imbalance on walking since 6 months. He had features of raised intracranial pressure with headache and vomiting since 2 weeks. He had an ataxic gait and bilateral papilledema on examination. General examination was normal. The MRI scan showed a lobulated lesion in the left lateral ventricle which was isointense on T1 and T2. The lesion had homogeneous contrast enhancement (Fig. 6). The child underwent left frontal craniotomy and transcortical approach was used with gross total excision of the lesion (Fig. 7). Frozen section as well as final histopathology report confirmed a transitional meningioma (WHO grade I). The child developed bilateral subdural hygromas and underwent subduro-peritoneal shunt after observation for a month with complete resolution of symptoms. However, 6 months later, the child developed hydrocephalus and needed insertion of a left ventriculo-peritoneal shunt and removal of subdural shunt. At 2 years follow-up, the child complained of loss of vision and developed weakness in all four limbs. On evaluation, he was found to have several nodular lesions in the CV junction, cervical spine, and other stigmata of neurofibromatosis type II (Fig. 8). Decompression was done by removing the largest lesion. He has recovered well except in terms of vision and is under follow-up of more than 3 years.

Introduction

Meningiomas are common brain tumors in adults, but occur very rarely in children. An intraventricular location sans dural attachment is unusual but has been reported in the past. Inside the ventricles, they arise from the arachnoid cells present within the choroid plexus, tela of the velum interpositum, and tela choroidea [1, 2]. Meningiomas account for less than 3% of brain tumors in children with intraventricular location constituting about 0.5 to 5% among them [3]. Management of these tumors is difficult owing to the depth of tumor, young age involved, large size of the lesion at presentation, increased vascularity, and absence of any neurological deficit which can add to the diagnostic difficulty.

Discussion

Meningiomas in children form a minority of cases as compared to a much higher incidence in adults. Conversely, the ratio of incidence of intraventricular meningiomas to intracranial tumors is higher in children than in adults [4]. In children, they tend to occur between 5 and 15 years of age [5]. As compared to their adult counterparts, pediatric meningiomas tend to have a higher grade on presentation and a more aggressive course [6]. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast administration is preferred for diagnosis. They are iso- to hypointense on T1 and T2WI but show intense enhancement on contrast administration. This helps to delineate the tumor and plan the surgical approach [7]. Remotely, they may be associated with cystic change. The radiological presentation in children is similar to that in adults except for the larger size of tumor seen in the pediatric age group [7]. Meningiomas inside the ventricles are slow-growing tumors that tend to become large prior to detection. The plausible hypothesis is the presence of a large space in the ventricles which allows for tumor expansion especially in the lateral ventricles. Owing to the large space within, the lateral ventricle is the commonest site of tumor noted followed by the third and fourth ventricle. Until the outflow channels are obstructed mechanically, signs and symptoms are mild and nonspecific. The usual presentation is with symptoms of raised intracranial pressure. The intraventricular location makes neurological examination and localization difficult due to the paucity of deficits. The fourth ventricular and third ventricular tumors may present with cerebellar signs and hypothalamic disturbances. Although the overall incidence of seizures is lesser in children than in adults, few patients may still present with generalized tonic clonic variant of seizures. Cushing and Eisenhardt [8] described the following five characteristic clinical features of lateral ventricle meningiomas:

-

(a)

Pressure symptoms often in the form of unilateral headache

-

(b)

Contralateral homonymous macular splitting hemianopia

-

(c)

Contralateral sensorimotor deficit (sensory involvement greater than motor involvement)

-

(d)

Cerebellar affection in more than half the cases

-

(e)

Dysphasic and paralexic disturbance in left-sided tumors

The peculiar deep location with possible attachments and hidden vascular pedicles makes it a challenging prospect to manage surgically. An endoscopic biopsy of these lesions may help in confirming the diagnosis and helps to plan further surgical approach but it is unlikely to help as a cerebrospinal fluid diversion technique. The definitive treatment remains surgery and total excision of the tumor is curative since the lesion is benign in nature. The possible differentials to be ruled out are choroid plexus papilloma, ependymoma, and astrocytoma. The extent of surgical tumor excision is the most important factor in prevention of recurrence. The tumor receives its blood supply from the branches of the internal carotid artery. A planned approach is necessary to minimize the blood loss and avoid postoperative morbidity. Due consideration must be given to critical structures such as the optic radiation which lie in close relation to the lateral ventricle. Radiation should be considered in cases with subtotal excision and a high grade, i.e., grade III. Meningiomas in children are known to occur in patients with neurofibromatosis type II (up to 40%) and in patients with radiation therapy taken in the past [4, 5]. Hence, a meticulous cutaneous and ophthalmological evaluation along with a detailed past history of the patient is necessary to rule them out. So far, an intraventricular location of meningioma has not been described in the reported cases of neurofibromatosis type II.

A brief tabulated summary of the 27 cases of primary intraventricular meningioma reported from 1955 till date is given in Table 1 [4, 6, 7, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Ciurea et al. [15] achieved complete excision of a large 7-cm lateral ventricular meningioma in a 4-year-old girl. The preoperative neurological deficits improved with time although she required drainage of a large subdural hygroma postoperatively which improved her motor weakness even further. Nambiar A. and his colleagues [18] reported a case of an 11-year-old boy with pyrexia of unknown origin with an intraventricular chordoid meningioma. The fever subsided after surgical excision of the same. He developed recurrence after 1 year and underwent repeat surgery with adjuvant fractionated radiotherapy. The largest single reported series of six cases of pediatric intraventricular meningiomas is by Dash et al. [21]. The mean age of presentation was 14.6 years with a male preponderance and headache was the most frequent presenting complaint. Five out of six patients had a single tumor while one patient presented with multiple meningiomas with concurrent neurofibromatosis type II. Transcortical approach via the superior parietal lobule, middle temporal gyrus approach, and transcallosal approach were the surgical techniques attempted. Transitional meningioma was the commonest pathological diagnosis. Follow-up after surgical excision ranged from 6 to 36 months and there were no reported recurrence in any case.

Conclusion

Intraventricular meningiomas are very rare brain tumors in children. The management of these tumors is complex yet well defined. Total surgical excision is the only curative treatment in spite of their deep location and vascularity. Endoscopic biopsy of these lesions can be safely performed for confirmation of diagnosis in doubtful cases. Possibility of neurofibromatosis should be considered in their management. Prognosis remains good in cases with complete surgical excision and careful handling of the vascular pedicles intraoperatively reduces the chances of postoperative morbidity and improves the quality of life.

References

Tung H, Apuzzo MLJ (1991) Meningiomas of the third ventricle. In: Al-Mefty O (ed) Meningiomas. Raven Press, New York, pp 583–591

Guidetti B, Delfini R (1991) Lateral and fourth ventricle meningiomas: In Al-Mefty O (ed): Meningiomas. New York, Raven Press, pp 569–587

Li J, Mzimbiri JM, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Liao X, Liu J (2016) Surviving the largest atypical parasagittal meningioma in a 2-year-old child: a case report and a brief review of the literature. World neurosurgery 87:662

Okechi H, Albright AL (2012) Intraventricular meningioma: case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg 48:30–34

Ravindranath K, Vasudevan MC, Pande A, Symss N (2013) Management of pediatric intracranial meningiomas: an analysis of 31 cases and review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 29(4):573–582

Munjal S, Vats A, Kumar J, Srivastava A, Mehta VS (2016) Giant pediatric intraventricular meningioma: case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci 11(3):219–222

Darling CF, Byrd SE, Reyes-Mugica M, Tomita T, Osborn RE, Radkowski MA, Allen ED (1994) MR of pediatric intracranial meningiomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 15(3):435–444

Cushing H, Eisenhardt L (1938) Meningiomas. Their classification, regional behaviour, life history and surgical end results: in Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; pp. 139–49.

Heppner F (1955) Meningiomas of the third ventricle in children; review of the literature and report of two cases with uneventful recovery after surgery. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand 30:471–481

Byard RW, Bourne AJ, Clark B, Hanieh A (1989) Clinicopathological and radiological features of two cases of intraventricular meningioma in childhood. Pediatr Neurosci 15:260–264

Huang PP, Doyle WK, Abbott IR (1993) Atypical meningioma of the third ventricle in a 6-year-old boy. Neurosurgery 33:312–315

Lozier AP, Bruce JN (2003) Meningiomas of the velum interpositum: surgical considerations. Neurosurg Focus 15:E11

Song KS, Park SH, Cho BK, Wang KC, Phi JH, Kim SK (2008) Third ventricular chordoid meningioma in a child. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2:269–272

Dulai MS, Khan AM, Edwards MS, Vogel H (2009) Intraventricular metaplastic meningioma in a child: case report and review of the literature. Neuropathology 29:708–712

Ciurea AV, Vapor I, Tascu A (2011) Intraventricular meningioma in a 4-year-old child: case presentation. Romanian Neurosurgery 3:306–309

Ramraje S, Kulkarni S, Choudhury B (2012) Paediatric intraventricular meningiomas. A report of two cases. Australas Med J 5(2):126–129

Moiyadi AV, Shetty P (2012) Giant velum interpositum meningioma in a child. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol 33:173–175

Nambiar A, Pillai A, Parmar C, Panikar D (2012) Intraventricular chordoid meningioma in a child: fever of unknown origin, clinical course, and response to treatment. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10:478–481

Kwee LE, van Veelen-Vincent ML, Michiels EM, Kros JM, Dammers R (2015) The importance of microsurgery in childhood meningioma: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 31:161–165

Prodromou N, Alexiou GA, Stefanaki K, Moraiti A, Sfakianos G (2016) Giant atypical intraventricular meningioma in a child. Pediatr Neurosurg 51(6):306–308

Dash C, Pasricha R, Gurjar H, Singh PK, Sharma BS (2016) Pediatric intraventricular meningioma: a series of six cases. J Pediatr Neurosci Jul-Sep 11(3):193–196

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that this manuscript is a unique submission and is not being considered for publication, in part or in full, with any other source in any medium. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muley, K.D., Shaikh, S.T., Deopujari, C.E. et al. Primary intraventricular meningiomas in children—experience of two cases with review of literature. Childs Nerv Syst 33, 1589–1594 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3483-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-017-3483-1