Abstract

Spinal epidural hematoma is a rare neurosurgical emergency in respect of motor and sensory loss. Identifiable reasons for spontaneous hemorrhage are vascular malformations and hemophilias. We presented a case of spontaneous epidural hematoma in an 18-year-old female patient who had motor and sensory deficits that had been present for 1 day. On MRI, there was spinal epidural hematoma posterior to the T2–T3 spinal cord. The hematoma was evacuated with T2 hemilaminectomy and T3 laminectomy. Patient recovered immediately after the surgery. Literature review depicted 112 pediatric cases (including the presented one) of spinal epidural hematoma. The female/male ratio is 1.1:2. Average age at presentation is 7.09 years. Clinical presentations include loss of strength, sensory disturbance, bowel and bladder disturbances, neck pain, back pain, leg pain, abdominal pain, meningismus, respiratory difficulty, irritability, gait instability, and torticollis. Most common spinal level was cervicothoracic spine. Time interval from symptom onset to clinical diagnosis varied from immediate to 18 months. Spinal epidural hematoma happened spontaneously in 71.8 % of the cases, and hemophilia was the leading disorder (58 %) in the cases with a definable disorder. Partial or complete recovery is possible after surgical interventions and factor supplementations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spinal epidural hematoma (SEH) is a rare neurosurgical emergency in respect of motor and sensory loss. SEH occurring without a trauma is called as spontaneous SEH (SSEH). Identifiable reasons for spontaneous hemorrhage are vascular malformations and bleeding disorders. Incidence of SSEH is 0.1/100,000, and SSEH is common in fourth and fifth decades of life [1, 2]. Prompt diagnosis is very important for timely intervention in children [3].

We present an 18-year-old female patient having SSEH and discuss the literature in respect of prevalence, diagnostic tools, treatment approaches, and outcomes of SSEH in pediatric patients.

Case report

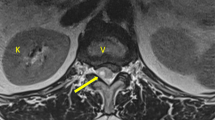

An 18-year-old girl was admitted to our clinic for difficulty in walking and sensory disturbances that had developed 1 day ago. In her neurologic exam, she was alert and oriented. She was paraparetic (strength of lower extremities = 2/5), and her sensory level was at T3 dermatome. Her deep tendon reflexes were normoactive, and Babinski was negative, bilaterally. In her medical history, there was no recent trauma, no familial bleeding disorder, or no anticoagulation treatment. On MRI, posterior to the spinal cord, there was a mass lesion in the epidural space at T2–T3 levels, which was isointense on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images compared to cerebrospinal fluid intensity, consistent with acute hematoma (Fig. 1a, b). She was taken to surgery after immediate clinical and laboratory evaluations had been completed. T2 hemilaminectomy and T3 laminectomy were performed in the operation. A blood clot was observed and was aspirated completely. Upper and lower spinal levels were clear for any additional presence of hematoma mass. No identifiable vascular malformation was noticed during decompression of the epidural space. Surgery was uneventful, and she recovered completely after the operation (Fig. 1c).

Discussion

Spinal hematomas are categorized into four groups: subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, and intramedullary. Spinal hematomas could lead to devastating results such as neurologic deficits and even death [3]. Spinal epidural hematoma, which is the most common type of spinal hematomas, presents rarely in pediatric population [2, 3]. Although there is confusion in definition of SSEH, we determined SEH that occurs without any trauma as SSEH. Identifiable underlying disorders beside trauma are spinal interventions, bleeding disorders, spinal infections, spinal tumors, and spinal vascular malformations [2, 4].

Spinal epidural hematoma in pediatric population was first described by Cooper in 1832 [5]. Literature review depicted 112 pediatric cases (including the presented one) of spinal epidural hematoma. Of these 112 patients, 70 were male and 39 were female (F:M = 1.1:2, sex was not mentioned in three cases). Average age at presentation was 7.09 years (range = 0–18 years). Clinical presentations include loss of strength, sensory disturbance, bowel and bladder disturbances, neck pain, back pain, leg pain, abdominal pain, meningismus, respiratory difficulty, irritability, gait instability, and torticollis. Clinical diagnosis is hard to make in infants, who have usually presented with non-specific symptoms such as irritability [3]. Most common spinal level was cervicothoracic spine (46.3 %). Other sites were thoracic (20 %), cervical (15.4 %), thoracolumbar (8.1 %), cervicolumbar (6.3 %), and lumbar (3.6 %). Time interval from symptom onset to clinical diagnosis varied from immediate to 18 months. Spinal epidural hematoma happened spontaneously in 71.8 % of the cases. Hemophilia was the leading disorder (58 %) in the cases with a known disease. Partial or complete recovery is possible after surgical interventions and factor supplementations (Table 1) [3, 5–73].

Exact pathogenesis of SSEH is not clear, yet. Spinal epidural venous plexus has been accused of bleeding source by many authors [3]. Spinal epidural venous plexus has no valves, and a sudden increase in pressure due to straining, voiding, crying, and coughing could lead to backflow of blood in the plexus and rupture of the venous vessels [2, 16, 40, 74]. There are infectious, inflammatory, and metastatic diseases in differential of SEH. Magnetic resonance imaging is superior to other diagnostic modalities in delineating location, consistency, and duration of the hematoma. Status of the spinal cord and any underlying pathology such as vascular malformations could also be evaluated with MRI [3]. In case of vascular malformations, additional imaging with angiography is necessary to better delineate the feeding and draining vessels.

Surgical decompression is the first-line treatment modality for SSEH [3, 40, 75, 76]. Laminectomy is the most effective decompressive approach in SSEH, yet it has some conflicts in pediatric patients due to progressive kyphotic deformity in upcoming years. For this reason, hemilaminectomy, laminotomy, and laminoplasty have been used in this patient population [3, 6–11, 14–16, 18–20, 22–24, 26, 28, 30–41, 45, 46, 48, 50, 52, 54–66, 77]. In our case, we preferred single-level laminectomy with single-level hemilaminectomy due to limited SSEH extension between T2 and T3 levels. In some cases with mild neurologic deficits and/or bleeding disorders, conservative approaches were preferred over surgical decompression [12, 13, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 42, 44, 49, 51, 53, 60, 61, 67–69]. The outcome of surgical interventions depends on preoperative neurological status of the patient, and the time interval passed from the onset of symptoms to surgery [3]. Critical deadline for timely intervention is 48 h for incomplete and 24 h for complete neurologic deficits [78]. The success rate of surgery is more profound in pediatric cases than adults, and even complete recovery has rarely been reported after late presentation [14, 40, 71, 72]. For this reason, delayed presentation and severe neurologic deficits are not contraindications for surgery if the patient does not have any underlying bleeding disorders [3, 5].

Conclusion

Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma is a rare neurosurgical emergency, especially in pediatric population. Response to surgery (in non-coagulopathy situation) is devastating in this patient population despite delayed surgical intervention and severity of neurologic deficits. However, surgery should not be delayed, as soon as bleeding disorders have been eliminated from differential diagnosis list, for a better and fast recovery.

References

Groen RJ, van Alphen HA (1996) Operative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas: a study of the factors determining postoperative outcome. Neurosurgery 39(3):494–508, discussion 508–509

Kreppel D, Antoniadis G, Seeling W (2003) Spinal hematoma: a literature survey with meta-analysis of 613 patients. Neurosurg Rev 26(1):1–49. doi:10.1007/s10143-002-0224-y

Schoonjans AS, De Dooy J, Kenis S, Menovsky T, Verhulst S, Hellinckx J, Van Ingelghem I, Parizel PM, Jorens PG, Ceulemans B (2013) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in infancy: review of the literature and the “seventh” case report. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 17(6):537–542. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.05.012

Riaz S, Jiang H, Fox R, Lavoie M, Mahood JK (2007) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma causing Brown-Sequard syndrome: case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med 33(3):241–244. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.02.032

Sim HB, Weon YC, Park JB, Yang DS (2010) Chronic traumatic spinal epidural hematoma in a child. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 89(11):936–940. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181ec9689

Wittebol MC, van Veelen CW (1984) Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma. Etiological considerations. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 86(4):265–270

Williams CE, Nelson M (1987) The varied computed tomographic appearances of acute spinal epidural haematoma. Clin Radiol 38(4):363–365

Ventureyra EC, Ghanem Q, Ivan LP (1979) Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma in a youngster. Childs Brain 5(2):103–108

Vallee B, Besson G, Gaudin J, Person H, Le Fur JM, Le Guyader J (1982) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a 22-month-old girl. J Neurosurg 56(1):135–138. doi:10.3171/jns.1982.56.1.0135

Tewari MK, Tripathi LN, Mathuriya SN, Khandelwal N, Kak VK (1992) Spontaneous spinal extradural hematoma in children. Report of three cases and a review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 8(1):53–55

Tender GC, Awasthi D (2004) Spontaneous cervical spinal epidural hematoma in a 12-year-old girl: case report and review of the literature. J La State Med Soc 156(4):196–198

Tailor J, Dunn IF, Smith E (2006) Conservative treatment of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma associated with oral anticoagulant therapy in a child. Childs Nerv Syst 22(12):1643–1645. doi:10.1007/s00381-006-0220-6

Sheikh AA, Abildgaard CF (1994) Medical management of extensive spinal epidural hematoma in a child with factor IX deficiency. Pediatr Emerg Care 10(1):26–29

Scott TE Jr (1958) Spinal epidural hemorrhage: spontaneous and recurrent. South Med J 51(8):1048–1050

Robertson WC Jr, Lee YE, Edmonson MB (1979) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in the young. Neurology 29(1):120–122

Ravid S, Schneider S, Maytal J (2002) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma: an uncommon presentation of a rare disease. Childs Nerv Syst 18(6–7):345–347. doi:10.1007/s00381-001-0540-5

Rao BD, Rao KS, Subrahmanian MV, Reddy MVR (1966) Spinal epidural haemorrhage. Br J Surg 53(7):649–650

Ramelli GP, Boscherini D, Kehrli P, Rilliet B (2008) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematomas in children: can we prevent a negative prognosis?–reflections on 2 cases. J Child Neurol 23(5):564–567. doi:10.1177/0883073807309777

Posnikoff J (1968) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma of childhood. J Pediatr 73(2):178–183

Poonai N, Rieder MJ, Ranger A (2007) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in an 11-month-old girl. Pediatr Neurosurg 43(2):121–124. doi:10.1159/000098385

Per H, Canpolat M, Tumturk A, Gumus H, Gokoglu A, Yikilmaz A, Ozmen S, Kacar Bayram A, Poyrazoglu HG, Kumandas S, Kurtsoy A (2014) Different etiologies of acquired torticollis in childhood. Childs Nerv Syst 30(3):431–440. doi:10.1007/s00381-013-2302-6

Pear BL (1972) Spinal epidural hematoma. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 115(1):155–164

Patel H, Boaz JC, Phillips JP, Garg BP (1998) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in children. Pediatr Neurol 19(4):302–307

Paraskevopoulos D, Magras I, Polyzoidis K (2013) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma secondary to extradural arteriovenous malformation in a child: a case-based update. Childs Nerv Syst 29(11):1985–1991. doi:10.1007/s00381-013-2214-5

Pan G, Kulkarni M, MacDougall DJ, Miner ME (1988) Traumatic epidural hematoma of the cervical spine: diagnosis with magnetic resonance imaging. Case report. J Neurosurg 68(5):798–801

Pai SB, Maiya PP (2006) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a toddler—a case report. Childs Nerv Syst 22(5):526–529. doi:10.1007/s00381-005-0002-6

Noth I, Hutter JJ, Meltzer PS, Damiano ML, Carter LP (1993) Spinal epidural hematoma in a hemophilic infant. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 15(1):131–134

Nirupam N, Pemde H, Chandra J (2014) Spinal epidural hematoma in a patient with hemophilia B presenting as acute abdomen. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 30(Suppl 1):54–56. doi:10.1007/s12288-013-0245-4

Narawong D, Gibbons VP, McLaughlin JR, Bouhasin JD, Kotagal S (1988) Conservative management of spinal epidural hematoma in hemophilia. Pediatr Neurol 4(3):169–171

Nagel MA, Taff IP, Cantos EL, Patel MP, Maytal J, Berman D (1989) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a 7-year-old girl. Diagnostic value of magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 91(2):157–160

Muhonen MG, Piper JG, Moore SA, Menezes AH (1995) Cervical epidural hematoma secondary to an extradural vascular malformation in an infant: case report. Neurosurgery 36(3):585–587, discussion 587–588

Moiyadi AV, Bhat DI, Devi BI, Mahadevan A, Shankar SK, Sastry KV (2005) Spinal epidural epitheloid hemangioma—case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 41(3):155–157. doi:10.1159/000085875

Miyagi Y, Miyazono M, Kamikaseda K (1998) Spinal epidural vascular malformation presenting in association with a spontaneously resolved acute epidural hematoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 88(5):909–911. doi:10.3171/jns.1998.88.5.0909

Min S, Duan Y, Jin A, Zhang L (2011) Chronic spontaneous cervicothoracic epidural hematoma in an 8-month-old infant. Ann Saudi Med 31(3):301–304. doi:10.4103/0256-4947.75586

Mayer JA (1963) Extradural spinal hemorrhage. Can Med Assoc J 89:1034–1037

Matsumae M, Shimoda M, Shibuya N, Ueda M, Yamamoto I, Sato O (1987) Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma. Surg Neurol 28(5):381–384

Lo MD (2010) Spinal cord injury from spontaneous epidural hematoma: report of 2 cases. Pediatr Emerg Care 26(6):445–447. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181e15ec0

Licata C, Zoppetti MC, Perini SS, Bazzan A, Gerosa M, Da Pian R (1988) Spontaneous spinal haematomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 95(3–4):126–130

Liao CC, Lee ST, Hsu WC, Chen LR, Lui TN, Lee SC (2004) Experience in the surgical management of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. J Neurosurg 100(1 Suppl Spine):38–45

Lee JS, Yu CY, Huang KC, Lin HW, Huang CC, Chen HH (2007) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a 4-month-old infant. Spinal Cord 45(8):586–590. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3101976

Kitagawa RS, Mawad ME, Whitehead WE, Curry DJ, Luersen TG, Jea A (2009) Paraspinal arteriovenous malformations in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 3(5):425–428. doi:10.3171/2009.2.PEDS08427

Kiehna EN, Waldron PE, Jane JA (2010) Conservative management of an acute spontaneous holocord epidural hemorrhage in a hemophiliac infant. J Neurosurg Pediatr 6(1):43–48. doi:10.3171/2010.4.PEDS09537

Kalina P, Morris J, Raffel C (2008) Spinal epidural hematoma in an infant as the initial presentation of severe hemophilia. Emerg Radiol 15(4):281–284. doi:10.1007/s10140-007-0667-0

Jost W, Graf N, Pindur G, Sitzmann FC (1990) Intraspinal, extradural hemorrhage in a 7-year-old boy with hemophilia B. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 138(1):36–37

Joseph AP, Vinen JD (1993) Acute spinal epidural hematoma. J Emerg Med 11(4):437–441

Jones RK, Knighton RS (1956) Surgery in hemophiliacs with special reference to the central nervous system. Ann Surg 144(6):1029–1034

Jackson R (1869) Case of spinal apoplexy. Lancet 94(2392):5–6

Jackson FE (1963) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma coincident with whooping cough. Case report. J Neurosurg 20:715–717. doi:10.3171/jns.1963.20.8.0715

Iwamuro H, Morita A, Kawaguchi H, Kirino T (2004) Resolution of spinal epidural haematoma without surgery in a haemophilic infant. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 146(11):1263–1265. doi:10.1007/s00701-004-0358-5

Iguchi T, Ito Y, Asai M, Ito J, Okada N, Murakami M (1993) A case of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. No To Hattatsu 25(3):267–270

Hutt PJ, Herold ED, Koenig BM, Gilchrist GS (1996) Spinal extradural hematoma in an infant with hemophilia A: an unusual presentation of a rare complication. J Pediatr 128(5 Pt 1):704–706

Hosoki K, Kumamoto T, Kasai Y, Sakata K, Ito M, Iwamoto S, Komada Y (2010) Infantile spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. Pediatr Int 52(3):507–508. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2010.03145.x

Hamre MR, Haller JS (1992) Intraspinal hematomas in hemophilia. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 14(2):166–169

Guzel A, Simsek O, Karasalihoglu S, Kucukugurluoglu Y, Acunas B, Tosun A, Cakir B (2007) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma after seizure: a case report. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 46(3):263–265. doi:10.1177/0009922806289427

Gupta V, Kundra S, Chaudhary A, Kaushal R (2012) Cervical epidural hematoma in a child. J Neurosci Rural Pract 3(2):217–218. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.98259

Grollmus J, Hoff J (1975) Spontaneous spinal epidural haemorrhage: good results after early treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 38(1):89–90

Faillace WJ, Warrier I, Canady AI (1989) Paraplegia after lumbar puncture. In an infant with previously undiagnosed hemophilia A. Treatment and peri-operative considerations. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 28(3):136–138

Doymaz S, Schneider J (2013) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a teenage boy with cholestasis: a case report. Pediatr Emerg Care 29(2):227–229. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e318280d682

Cooper DW (1967) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 26(3):343–345. doi:10.3171/jns.1967.26.3.0343

Chuang NA, Shroff MM, Willinsky RA, Drake JM, Dirks PB, Armstrong DC (2003) Slow-flow spinal epidural AVF with venous ectasias: two pediatric case reports. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 24(9):1901–1905

Chretiennot-Bara C, Guet A, Balzamo E, Noseda G, Torchet MF, Rothshild C, Blakime P, Schmit P (2001) Epidural hematoma in a child with hemophilia: diagnostic difficulties. Arch Pediatr 8(8):828–833

Chang CW, Lin LH, Liao HT, Hung KL, Hwan JS (2002) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a 5-year-old girl. Acta Paediatr Taiwan 43(6):345–347

Calliauw L, Dhara M, Martens F, Vannerem L (1988) Spinal epidural hematoma without lesion of the spine. Report of 4 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 90(2):131–136

Caldarelli M, Di Rocco C, La Marca F (1994) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in toddlers: description of two cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol 41(4):325–329

Cabral AJ, Barros A, Aveiro C, Vasconcelos R (2011) Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma due to arteriovenous malformation in a child. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3875

Blount J, Doughty K, Tubbs RS, Wellons JC, Reddy A, Law C, Karle V, Oakes WJ (2004) In utero spontaneous cervical thoracic epidural hematoma imitating spinal cord birth injury. Pediatr Neurosurg 40(1):23–27. doi:10.1159/000076573

Bisson EF, Dumont T, Tranmer B (2007) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a child with hemophilia B. Can J Neurol Sci 34(4):488–490

Balkan C, Kavakli K, Karapinar D (2006) Spinal epidural haematoma in a patient with haemophilia B. Haemophilia 12(4):437–440. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2516.2006.01286.x

Azumagawa K, Yamamoto S, Tanaka K, Sakanaka H, Teraura H, Takahashi K, Tamai H (2012) Non-operative treated spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a 12-year-old boy. Pediatr Emerg Care 28(2):167–169. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e318244785d

Abbas A, Afzal K, Mujeeb AA, Shahab T, Khalid M (2013) Spontaneous ventral spinal epidural hematoma in an infant: an unusual presentation. Iran J Child Neurol 7(2):47–50

Lim JJ, Yoon SH, Cho KH, Kim SH (2008) Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in an infant: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 44(2):84–87. doi:10.3340/jkns.2008.44.2.84

Pecha MD, Able AC, Barber DB, Willingham AC (1998) Outcome after spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in children: case report and review of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79(4):460–463

Foo D, Rossier AB (1982) Post-traumatic spinal epidural hematoma. Neurosurgery 11(1 Pt 1):25–32

Solheim O, Jorgensen JV, Nygaard OP (2007) Lumbar epidural hematoma after chiropractic manipulation for lower-back pain: case report. Neurosurgery 61(1):E170–E171. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000279740.61048.e2, discussion E171

Shin JJ, Kuh SU, Cho YE (2006) Surgical management of spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma. Eur Spine J 15(6):998–1004. doi:10.1007/s00586-005-0965-8

Lawton MT, Porter RW, Heiserman JE, Jacobowitz R, Sonntag VK, Dickman CA (1995) Surgical management of spinal epidural hematoma: relationship between surgical timing and neurological outcome. J Neurosurg 83(1):1–7. doi:10.3171/jns.1995.83.1.0001

Hehman K, Norrell H (1968) Massive chronic spinal epidural hematoma in a child. Am J Dis Child 116(3):308–310

Halim TA, Nigam V, Tandon V, Chhabra HS (2008) Spontaneous cervical epidural hematoma: report of a case managed conservatively. Indian J Orthop 42(3):357–359. doi:10.4103/0019-5413.41863

Acknowledgments

Murat Şakir Ekşi, M.D. was supported by a grant from Tubitak (The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey), grant number: 1059B191400255.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Babayev, R., Ekşi, M.Ş. Spontaneous thoracic epidural hematoma: a case report and literature review. Childs Nerv Syst 32, 181–187 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-015-2768-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-015-2768-5