Abstract

To explore the associated risk factors of symptomatic knee osteonecrosis (KON) in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), we conducted a retrospective case–control study to compare the clinical and laboratory features between SLE patients with and without symptomatic KON matched by age and gender. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were used to evaluate possible associated risk factors. Twenty (one male, nineteen females) out of 3941 lupus patients were identified as symptomatic KON, which was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging. The mean age at KON onset was 34.4 (range 12–67) years, and the median course of lupus at KON onset was 72.5 (range 8–123) months. Univariate and multivariate analyses identified that the prevalence of cutaneous vasculitis (OR 5.23; 95 % CI 1.11–24.70), hyperfibrinogenemia (OR 4.75; 95 % CI 1.08–20.85), and elevated IgG levels (OR 6.05; 95 % CI 1.58–23.16) were statistically higher in KON group, and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) usage was statistically lower in KON group (OR 0.27; 95 % CI 0.07–0.97). Glucocorticoid usage, in terms of maximal dose, duration of treatment, and the percentage of receiving methylprednisolone pulse therapy, did not show statistical difference between the two groups (p > 0.05). Symptomatic KON is a relatively rare complication of SLE. Cutaneous vasculitis, hyperfibrinogenemia, and elevated IgG levels are possible risk factors, whereas HCQ may provide a protective effect. Our results suggest that lupus activity as well as hypercoagulation status may play a role in the pathogenesis of KON in lupus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteonecrosis is a common bone complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), which is reported in 3–30 % lupus patients [1–7]. The key mechanism of osteonecrosis (ON) is destruction of the nourishing vessels of bone, which leads to osseous ischemia, degeneration, and necrosis [8]. The most common site of ON is femoral head, while knee and shoulder ON are less frequent [9]. Knee osteonecrosis (KON) typically involves the distal femur and proximal tibia, and presents with asymptomatic or symptomatic pain around the knees, which mimics the symptoms of lupus-associated non-erosive arthritis. Similar to femoral head necrosis (FHN), KON is an important disabling bone complication with increased risk of developing septic arthritis. Early diagnosis and intervention are essential for better outcome of KON. Given the insidious feature of ON, to clarify the possible risk factors for KON could help clinicians to identify susceptible individuals and provide prophylactic suggestions. However, few data on KON are available to date. The proposed risk factors of osteonecrosis including glucocorticoid (GC) use, presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) or antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), lupus disease activity, vasculitis and cytotoxic treatment [1, 3–6, 10–12], mainly derive from FHN studies, and conflicting results have been derived from clinical studies [1, 6, 13]. To this point, we conducted a retrospective case–control study to summarize the clinical features of SLE patients with symptomatic KON and explore the possible associated risk factors.

Methods

Patients and controls

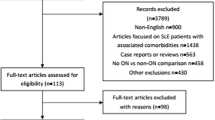

The medical records of 3941 SLE in-patients at Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing China) from January 2008 to December 2014 were retrospectively reviewed.

Patients: A total of 20 patients with symptomatic KON confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were included.

Controls: Eighty age- and gender-matched lupus patients without symptomatic KON admitted during this period were randomly selected as controls with a ratio of 1:4 (KON: control). All patients fulfilled the 2009 Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinic revision of the American College of Rheumatology Classification Criteria for SLE [14]. SLE disease activity at the time of KON was evaluated using the SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) [15]. The local institutional review board approved this study. Since the study based on a review of medical records which has been obtained for clinical purposes, the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Statistical analysis

Data regarding clinical features, laboratory indices, and treatment history were collected and compared between the KON and the control group. Chi-square test (χ 2 test), Student’s t test, and Mann–Whitney test were used to analyze categorical data, numerical data with normal distribution, and numerical data without normal distribution, respectively. A univariate analysis was performed to determine variables associated with symptomatic KON. A multivariate logistic stepwise regression was performed with all independent variables with a p < 0.05; a stepwise forward method was used for variable selection. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS version 19 was used for all data analyses.

Results

Patient demographics

Twenty patients (nineteen females, one male) were diagnosed with symptomatic KON and the mean age was 34.4 (range 12–67) years at KON onset. All the symptomatic KON patients had no history of smoking, alcohol abuse, oral contraceptives, or trauma. The median course of lupus at KON onset and the median duration of KON symptoms to diagnosis were 72.5 (range 8–123) months and 2 (range 1–24) months, respectively.

Articular manifestations in SLE patients with systemic KON: symptoms and imaging

All the patients in symptomatic KON group reported pain with or without tenderness on the affected knee(s). Swollen knees and limited motion of the lower limbs were observed in 9 and 11 patients, respectively. Additionally, complicated septic arthritis happened in two patients with the consequence of severe functional impairment. Lesions on MRI were shown as irregular, annular-shaped long T1 and long T2 signals on T1WI and T2WI short tau inversion recovery in the proximal tibia and/or distal femur (Fig. 1). Abnormal plain film findings were observed in 3/14 patients (21.4 %). Bilateral KON were documented in twelve patients (60 %). Half of the patients (10 patients, 50 %) developed simultaneous distal femur and proximal tibia involvement. Distal tibia involvement complicated with calcaneus osteonecrosis was observed in three patients. FHN was found only in four patients (Table 1).

Systemic manifestation in SLE patients with symptomatic KON

For those patients with symptomatic KON, the mean SLEDAI at the time of KON was 8.95 ± 7.0 (range 2–23). Rash (15 patients, 75 %) was the most commonly occurred initial symptom of lupus in this cohort. During disease development, cutaneous vasculitis, livedoreticularis and Raynaud phenomenon have been occurred to seven patients (35 %), three patients (15 %) and nine patients (45 %), respectively, and two of these patients had all the three manifestations simultaneously. Lupus nephritis (11 patients, 55 %) and hematologic involvement (16 patients, 80 %) were also very common. Four patients (20 %) had neuropsychiatric involvement. Serositis, seen in two patients (10 %), and thrombosis events, seen in one patient (5 %), were rather rare (Table 2).

Comparison between SLE Cases with and without symptomatic KON

The majority of patients in both groups had multiple systemic involvements, and APS complications, comorbidities of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia were comparable between KON group and the control group. No significant difference in arthritis occurrence was observed between the two groups. Moreover, visceral involvements, including hematological disorders, lupus nephritis, neuropsychiatric lupus, and pulmonary hypertension, were not significantly different between the two groups (p > 0.05). But the prevalence of cutaneous vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, hyperfibrinogenemia, elevated IgG levels, and positive aPL were all significantly higher in KON group (p < 0.05). SLEDAI at the onset of KON is not significantly different from that of the control group (p > 0.05). Differences of other laboratory findings between the two groups, including hypoalbuminemia, hypocomplementemia, and serum autoantibodies profile, were unremarkable (Table 2).

The multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that SLE patients with cutaneous vasculitis (OR 5.23; 95 % CI 1.11–24.70), hyperfibrinogenemia (OR 4.75; 95 % CI 1.08–20.85), and elevated IgG levels (OR 6.05; 95 % CI 1.58–23.16) had a significantly increased risk of developing KON, while hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) intake (OR 0.27; 95 % CI 0.07–0.97) seemed to protect lupus patients against the development of KON (Table 3).

Before the occurrence of KON, all the patients in both groups had received GC treatment. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were found in the initial dose (the median and the interquartile range IQR were 60 mg/day and 50–60 mg/day vs. 50 mg/day and 46.25–60 mg/day, respectively), the maximal dose (the median and the IQR were 72.5 mg/day and 60–625 mg/day vs. 100 mg/day and 60–1250 mg/day, respectively), or the duration of GC treatment (the median and the IQR were 36 months and 16.5–83 months vs. 32 months and 9–60 months, respectively) between symptomatic KON group and the control group. Development of symptomatic KON after GC therapy occurred as early as 1 week after pulse methylprednisolone therapy in one patient, and within 2 months in two patients. The percentage of patients receiving methylprednisolone pulse therapy between KON and the control group was not significantly different (30 % vs. 45 %, p > 0.05). However, HCQ usage was less frequent in KON group (35 % vs. 63.8 %, respectively; p = 0.020; Table 2).

Treatment and prognosis for SLE patients with symptomatic KON

Patients with active disease were administered medium-to-large doses of GCs and potent immunosuppressive agents. GC tapering combined with or without low-dose immunosuppressive agent regimen was applied to patients with stable disease. All patients were given HCQ, aspirin, calcium, and vitamin D after the diagnosis of KON; for those with osteoporosis, diphosphonate was administrated. Most of our patients showed relief of pain and improvement in motor ability. During the time of follow-up (2 months–6 years), one patient with recurrent osteonecrosis developed purulent arthritis after the recent episode of KON, and received joint rinsing and a long course of intravenous antibiotics. In addition, two patients developed FHN during follow-up. In four patients with repeated X-ray or MRI examinations, no progression of KON was observed at a 3- to 5-year follow-up.

Discussion

In this study, by using multivariate analysis, cutaneous vasculitis, hyperfibrinogenemia, and elevated IgG levels were identified as potential risk factors for symptomatic KON in SLE patients. Unexpectedly, GC dosage was not correlated with KON, and HCQ was shown to be a possible protective factor.

Cutaneous vasculitis was frequently presented in KON patients compared to control patients (35 % vs 7.5 %). Cutaneous vasculitis is generally considered as a sign of active disease and also included in the disease activity indexes such as SLEDAI. Osteonecrosis is more prevalent in lupus patients than in other autoimmune or systemic diseases [16–18], and it has been also reported that lupus disease activity is a fundamental risk factor of osteonecrosis [10]. Cutaneous vasculitis existence may suggest a subpopulation of active lupus patients, in whom active disease participates in the pathogenesis of KON. But we did not observe the correlation of disease activity measured by SLEDAI with the occurrence of symptomatic KON. The possible explanations are the limitations inherent in SLEDAI as well as the relatively small sample size of our study.

Elevated IgG level was shown to relate to KON, which has not been reported before. Abnormalities of B cell and plasma cell, which are responsible for autoantibody production, are the fundamental pathogenic mechanisms of SLE. Hyperglobulinaemia correlates with lupus activity to certain extent. As mentioned above, the active disease is an independent risk factor of ON, which may partially explain the high frequency of elevated IgG level in KON patients.

Hypercoagulation status and microvascular thrombosis are proposed to participate in the pathogenesis of KON. In our study, thrombocytopenia and positive aPL were statistically significant in univariate analysis, as well as hyperfibrinogenemia which was also confirmed by multivariate analyses, indicating hypercoagulation status may play an important role in KON and prophylactic aspirin may be of benefit. However, the association of aPL with osteonecrosis in SLE is controversial [2–4, 6, 19, 20], which justify further studies with a larger sample cohort to elucidate this issue.

Exogenous GCs, an important risk factor for aseptic osteonecrosis [12, 21–24], could promote fat emboli and increase intraosseous pressure secondary to adipocyte hypertrophy and subsequently contribute to bone ischemia [8]. In our study group, two patients developed KON 2 months after receiving high dose of GCs, and one patient developed KON just 1 week after pulse methylprednisolone therapy. Unexpectedly, we did not find that exogenous GCs was closely related with KON (p > 0.05). Nevertheless, some other studies have reported that patients can experience osteonecrosis before GCs treatment [1, 25]. Oinuma et al. [9] found that the onset of osteonecrosis in SLE patients could occur very early in the course of the disease, even within the first month of high-dose corticosteroid treatment. Wichak et al. [1] postulated that osteonecrosis was related to the duration of SLE, because the risk of disease exacerbation and exposure to steroids were both increased with prolonged clinical courses.Thus the association of GCs with KON is still pending and more evidence are needed.

One striking finding of our study is HCQ seemed to be a protective factor of KON. Antimalarial drugs are proposed to potentially reduce the risk of FHN by decreasing cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein levels, and lowering the incidence of thromboembolic events through inhibiting platelet aggregation and suppressing the binding of aPL to phospholipid surface [15, 26, 27]. Antimalarial drugs also contribute to sustained remission of lupus. Similarly, protective effects of HCQ against osteonecrosis have been reported in Thai patients with SLE [27].

The prevalence of FHN is much higher than that of KON, but in our cohort, the concomitant presentation of FHN only occurred in four patients of KON group, indicating that the predisposing risk factors for these two conditions are not same. We propose that KON and FHN may have different pathogenetic mechanisms.

Our study also has limitations. First, the patients were sampled from a single, university-based, nationwide referral center, which might introduce a selection bias toward severe cases. Second, only symptomatic MRI-confirmed KON cases were enrolled, the majority of which were diagnosed within the last 4 years, probably due to the implementation of nationwide MRI application within the past few years. Thus, asymptomatic KON and those with symptoms but mistaken for lupus arthritis or unconfirmed by plain X-ray were not included, which may lead to underestimation of the prevalence of KON. Third, MRI has not been routinely screened in asymptomatic patients of the control group, which might include asymptomatic KON cases. Finally, data integrity for more detailed medication information might be compromised in such a retrospective study. A large-scale prospective study is warranted,which is, however, difficult to conduct due to the low incidence of KON in SLE. Nevertheless, this study suggests certain risk factors for KON, which are valuable for clinical practice.

Conclusion

KON in SLE is a complication involving multiple mechanisms. Cutaneous vasculitis, elevated IgG levels, and hyperfibrinogenemia are likely risk factors for KON in SLE patients, while HCQ usage may act as a protective factor.

References

Kunyakham W, Foocharoen C, Mahakkanukrauh A, Suwannaroj S, Nanagara R (2012) Prevalence and risk factor for symptomatic avascular necrosis development in Thai systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 30:152–157

Migliaresi S, Picillo U, Ambrosone L et al (1994) Avascular osteonecrosis in patients with SLE: relation to corticosteroid therapy and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lupus 3:37–41

Mont MA, Glueck CJ, Pacheco IH, Wang P, Hungerford DS, Petri M (1997) Risk factors for osteonecrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 24:654–662

Mok CC, Lau CS, Wong RW (1998) Risk factors for avascular bone necrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol 37:895–900

Asherson RA, Liote F, Page B et al (1993) Avascular necrosis of bone and antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 20:284–288

Mok MY, Farewell VT, Isenberg DA (2000) Risk factors for avascular necrosis of bone in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: is there a role for antiphospholipid antibodies? Ann Rheum Dis 59:462–467

Klippel JH, Gerber LH, Pollak L, Decker JL (1979) Avascular necrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: silent symmetric osteonecroses. Am J Med 67:83–87

Gruson KI, Kwon YW (2009) Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 67:6–14

Oinuma K, Harada Y, Nawata Y et al (2001) Osteonecrosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus develops very early after starting high dose corticosteroid treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 60:1145–1148

Fialho SC, Bonfa E, Vitule LF et al (2007) Disease activity as a major risk factor for osteonecrosis in early systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 16:239–244

Haque W, Kadikoy H, Pacha O, Maliakkal J, Hoang V, Abdellatif A (2010) Osteonecrosis secondary to antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report, review of the literature, and treatment strategy. Rheumatol Int 30:719–723

Calvo-Alen J, McGwin G, Toloza S et al (2006) Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US cohort (LUMINA): XXIV. Cytotoxic treatment is an additional risk factor for the development of symptomatic osteonecrosis in lupus patients: results of a nested matched case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 65:785–790

Rascu A, Manger K, Kraetsch HG, Kalden JR, Manger B (1996) Osteonecrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus, steroid-induced or a lupus-dependent manifestation? Lupus 5:323–327

Petri M, Orbai AM, Alarcon GS et al (2012) Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 64:2677–2686

Belizna C (2015) Hydroxychloroquine as an anti-thrombotic in antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun Rev 14:358–362

Fukushima W, Fujioka M, Kubo T, Tamakoshi A, Nagai M, Hirota Y (2010) Nationwide epidemiologic survey of idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468:2715–2724

Shigemura T, Nakamura J, Kishida S et al (2011) Incidence of osteonecrosis associated with corticosteroid therapy among different underlying diseases: prospective MRI study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 50:2023–2028

Wang XS, Zhuang QY, Weng XS, Lin J, Jin J, Qian WW (2013) Etiological and clinical analysis of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in Chinese patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 126:290–295

Nagasawa K, Ishii Y, Mayumi T et al (1989) Avascular necrosis of bone in systemic lupus erythematosus: possible role of haemostatic abnormalities. Ann Rheum Dis 48:672–676

Alarcon-Segovia D, Deleze M, Oria CV et al (1989) Antiphospholipid antibodies and the antiphospholipid syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: a prospective analysis of 500 consecutive patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 68:353–365

Lane NE (2006) Therapy insight: osteoporosis and osteonecrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2:562–569

Weinstein RS (2010) Glucocorticoids, osteocytes, and skeletal fragility: the role of bone vascularity. Bone 46:564–570

Zizic TM, Marcoux C, Hungerford DS, Dansereau JV, Stevens MB (1985) Corticosteroid therapy associated with ischemic necrosis of bone in systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med 79:596–604

Heimann WG, Freiberger RH (1960) Avascular necrosis of the femoral and humeral heads after high-dosage corticosteroid therapy. N Engl J Med 263:672–675

Leventhal GH, Dorfman HD (1974) Aseptic necrosis of bone in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 4:73–93

Olsen NJ, Schleich MA, Karp DR (2013) Multifaceted effects of hydroxychloroquine in human disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 43:264–272

Uea-areewongsa P, Chaiamnuay S, Narongroeknawin P, Asavatanabodee P (2009) Factors associated with osteonecrosis in Thai lupus patients: a case control study. J Clin Rheumatol 15:345–349

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7152120), Chinese Medical Association (12040670367), National Natural Science Foundation of China (CN) (81571598) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (CN) (81550023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This is a retrospective study based on a review of medical records obtained for clinical purpose, and the requirement for written informed consent was waived. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Lidan Zhao and Xiuhua Wu have contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Wu, X., Wu, H. et al. Symptomatic knee osteonecrosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case–control study. Rheumatol Int 36, 1105–1111 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3502-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-016-3502-7