Abstract

Purpose

To analyse subjective and objective long-term outcomes of patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-deficient knees and limited demands regarding sportive activities. This subgroup of patients might be well-treated without ligament reconstruction.

Methods

We included 303 patients with unilateral tears of the ACL and conservative treatment into a prospective study. Mean age at injury was 33.8 (min. 18, max. 66) years. Follow-up was 27.1 (min. 21.3, max. 31.5) years. Follow-up examinations were conducted 12 and 27 years after injury. At the last follow-up we analysed 50 patients completely. To evaluate clinical and radiological outcomes we used the Lysholm score, Tegner activity scale, visual analogue scale for pain (VAS-pain), KOOS and Sherman score.

Results

Subjective outcome (Lysholm score and VAS-pain scale) improved between the 12th and 27th year after anterior cruciate ligament tear. At the same time activity level (Tegner activity scale) decreased. Also, arthritis (Sherman score) worsened over time. Twenty-seven years after injury, 90 % of the patients rated their ACL-deficient knee as normal or almost normal; 10 % of the patients rated it as abnormal. The findings of this study show that there is a subgroup of patients with ACL tears who are well treated with physiotherapy alone, not reconstructing the ligament. Also, other authors found this correlation between activity level reduction and better subjective outcome.

Conclusions

Conservative treatment of an ACL tear is a good treatment option for patients with limited demands regarding activity. Patient age, sportive activities and foremost subjective instability symptoms in daily life should be considered when deciding for or against ACL reconstruction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL)-deficient knees are prone to secondary joint pathologies like meniscal tears. ACL reconstruction is recommended in young and active patients and in severe anterior instabilities with a giving-way phenomenon in daily life [1, 2]. ACL reconstruction reduces the probability of secondary meniscal tears, but it cannot prevent osteoarthritis [3–7]. Matched-pair analyses comparing patient outcomes of conservatively treated ACL tears with ACL reconstruction showed similar mid- to long-term results [8, 9]. In children and adolescents, favourable results for ACL reconstruction over non-operative treatment were found [10].

It is not known for which patients conservative treatment is an equivalent or better treatment option than operative treatment.

We hypothesise that a subgroup of patients with ACL tears, who had limited activity levels before the injury, might be well-treated conservatively.

Patients and methods

In January 1985, we started a mono-centric prospective study in the Koenig-Ludwig-Haus Orthopaedic Clinic, University of Wuerzburg, Germany. Inclusion criteria were traumatic ACL tear and decision not to reconstruct the ligament.

Decision for non-reconstructive versus reconstructive treatment was made together with the patient in individuals who showed a tendency for a less active lifestyle and absence of severe subjective instability symptoms in daily life.

All patients received arthroscopy of the injured knee by the senior author to confirm complete ACL tear without reconstructing the ligament.

Exclusion criteria were bilateral injuries, knee luxation, fracture, tear of the posterior cruciate ligament or posterolateral instability, surgery of the same joint in the past, and decision for ACL reconstruction.

Posterior instability was diagnosed using the posterior drawer test, posterolateral instability was diagnosed by finding increased posterior tibial head translation during the posterior drawer test in external rotation.

All patients received physiotherapy with training of the active dynamic knee stabilisers.

Follow-up evaluations were conducted in our outpatient clinic on average 12 and 27 years after ACL tear. This was ten and 25 years after arthroscopy.

We analysed clinical outcomes using the Lysholm score [11], Tegner activity scale [12], visual analogue scale for pain (VAS-pain) [13] and the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [14]. The Lysholm score is a patient questionnaire used for subjective evaluation of knee function and symptoms ranging from bad (0 points) to very good (100 points). The Tegner activity scale describes the level of activity (0–10). The KOOS is an extensive outcome score with several subscales using 0–100 points, where 100 is the best possible result. For radiological evaluation during follow-up, we conducted standard X-rays of the knee (AP, lateral, patella) and used the score of Sherman et al. [15, 16].

For data management, Microsoft Excel was used. For statistical analysis, we used the SPSS 19.0 program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). After testing for normal distribution with the Kolmogorow-Smirnow test, we used the Mann-Whitney U test, the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Spearman correlation. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Until March 1996, 303 patients met the study criteria. 228 patients took part in the study. Mean age at injury was 33.8 (min. 18, max. 66) years. 78 % of the patients were men and 22 % were women. The right knee was injured in 59 %, the left knee in 41 %.

In 71.5 % of the cases, the ACL tear happened during sports: soccer (48.9 %), skiing (26.1 %), handball (8.0 %), or other (17.0 %). ACL tears that happened during work, recreation, or house-work constituted 28.5 %.

On average, arthroscopy was performed two years (min. 1 day, max. 5 years) after injury. In 71.9 % accompanying tears to the medial (60.5 %) or lateral (51.7 %) meniscus were found. They were partially resected. Only in one case an outside-in reconstruction was performed.

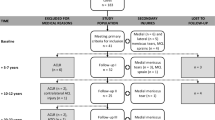

Follow-up was 27.1 (min. 21.3, max. 31.5) years. At a mean of 12.0 years of follow-up (min. 6.2, max. 16.4), we examined 181 patients. Two patients had died because of internal diseases, 17 patients could not be located, and 18 patients refused to come to the first follow-up examination of the study. After 27 years we could locate 127 patients. Twenty-eight patients (22 %) had one of the following knee surgery in the meantime: ACL reconstruction (n = 13) or arthroplasty (n = 15). They were excluded from further evaluation. Out of 99 patients left, 50 accepted not only clinical but also radiological examinations. We fully evaluated those 50 patients after 27.1 (min. 21.3, max. 31.5) years of follow-up. At this last follow-up we were able to examine 99 patients clinically, but not all of these patients could be evaluated also radiographically as mentioned above.

At time of diagnosis, patients without medial or lateral meniscal tears showed better Lysholm scores (83.7) than patients who had an accompanying tear of the medial or lateral meniscus (77.3), p = 0.25. More meniscal lesions were found in older patients and in cases with a longer time-span between tear of the anterior cruciate ligament and the diagnosing arthroscopy (Table 1).

During follow-up, 5 % of cases received an arthroscopic meniscal resection due to a symptomatic secondary meniscal tear.

In the study population subjective patient outcome (Lysholm score and VAS-pain) improved between both follow-up examinations (on average 12.0 and 27.1 years after injury). At the same time, activity level (Tegner activity scale) significantly decreased. Also, arthritis (Sherman score) and knee function gradually worsened over time (Table 2).

Patients with worse Lysholm scores also showed lower activity levels on the Tegner activity scale at last follow-up (Table 3). Patient age did neither correlate with the Lysholm score nor Tegner activity scale, but Lysholm score at last follow-up showed a significant correlation with time since injury (Table 4). We found a tendency for a better Lysholm score in females (84.6) than in males (79.0), p = 0.24.

Over time, activities of daily life and KOOS worsened. We found these parameters to be better in younger patients than in older individuals of the study (Fig. 1).

For KOOS subscales and arthritis index, we found worse results in patients with meniscal tears than in patients with intact medial and lateral meniscus at the time of arthroscopy (Table 5). Also, Sherman scores correlated with meniscal results (Fig. 2). Patients with lower Sherman scores than the average study population likewise showed worse results in KOOS and VAS subscales (Table 6).

We found a reduced thigh circumferential measure of 1-5 cm in 25 % of the patients. We did not find any significant differences in range of motion in the injured knee compared with the contralateral side. No extension deficit of 5° or greater was detected.

At last follow-up, on average 27.1 (min. 21.3, max. 31.5) years after ACL tear, patients subjectively rated their knee function as normal (28 %), almost normal (62 %), abnormal (10 %) or severely abnormal (0 %).

Discussion

We found good subjective long-term outcome in patients with limited demands regarding activities after ACL tear. Verifying our hypothesis, subjective patient outcome was much better than objective outcome. On average 27.1 (min. 21.3, max. 31.5) years after ACL tear 90 % of the patients rated their injured knee as normal or almost normal.

Although activity, function and arthritis worsened over time, quality of life and patient satisfaction were good at last follow-up 27 years after ACL tear. Actually, Lysholm score and VAS-pain improved between follow-up examinations 12 and 27 years after injury (Table 2).

These findings indicate that there is a subgroup of patients with ACL tears, who are well-treated with physiotherapy alone—not reconstructing the ligament. Also, other authors found this correlation between activity level reduction and better subjective outcome [17]. They also showed that patients with high demands on sportive activities were better treated by ACL reconstruction [17].

In our study population with ACL tears, we found more accompanying meniscal tears in older patients than in younger patients (Table 1). This is probably due to degenerative tissue changes and reduced elasticity of the meniscus in older individuals. We also found a correlation between prevalence of meniscal tears at time of diagnosing arthroscopy and time since injury (Table 1). This indicates anterior knee joint instability being a risk factor for secondary meniscal tears and is in line with other studies [3, 18].

At last follow-up, Lysholm score was almost independent from patient age, but Lysholm score was significantly worse in patients with a longer time since ACL tear (Table 4). This demonstrates ACL tear being a significant incident in a person’s life leading to worsening subjective ratings over time.

There is no general recommendation for or against ACL reconstruction [19, 20]. Some studies reported better outcome after non-operative treatment of ACL tears [9, 21]; other studies reported favourable results after ACL reconstruction [22–24]. Patient selection seems to be of significant importance.

After ACL tear, post-traumatic knee joint degeneration usually becomes clinical relevant about eight years after injury [20]. This is found in patients with or without ligament reconstruction [25–29]. ACL reconstruction several years after trauma with manifest degenerative changes might aggravate pain and joint degeneration [30–32].

The radiographic Sherman score correlated significantly with KOOS and VAS (Table 6). As this study population did not feel subjective instability symptoms after ACL tear, post-traumatic degenerative changes to the knee joint seem to be the primary cause of pain and reduced quality of life in these patients.

Analysing our data and published literature, we could not find a single instrument qualified to identify patients suitable for conservative treatment after ACL tear. Subjective instability symptoms like the giving-way phenomenon in daily life have shown to be the best anamnestic sign that ligament reconstruction is appropriate. On the other hand, individuals suitable for conservative treatment are patients with limited demands on activity. Typically, they are older than 30 years and not involved in ball or other high impact sports [33].

In regards to arthroscopy of the knee, technology and technique improved over time. At the start of this study in 1985, we already had video arthroscopy available and used it frequently in all knee arthroscopies. Also back then, we used standard anterolateral and anteromedial portals, as we still do in 2016. Over time the video quality improved. At the same time, we as surgeons became more experienced and better in evaluating the normal anatomy and pathologies in the knee joint. In our opinion, technological progress, but even more surgical experience helped to improve knowledge about detailed anatomy and pathologies of the intra-articular knee joint structures. In this regards, we emphasise the importance of evaluating also the posteromedial aspect of the intra-articular knee by moving the arthroscope far posterior between the medial femoral condyle and the cruciate ligaments into the posteromedial compartment. Otherwise ACL tear accompanying posterior medial meniscal root injuries might be missed.

Conclusions

Conservative treatment of ACL tear is a good treatment option for patients with limited demands regarding activity. Patient age, sportive activities, and foremost subjective instability symptoms in daily life should be considered when deciding for or against anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

References

Matic A, Petrovic Savic S, Ristic B, Stevanovic VB, Devedzic G (2016) Infrared assessment of knee instability in ACL deficient patients. Int Orthop 40:385–391

Shabani B, Bytyqi D, Lustig S, Cheze L, Bytyqi C, Neyret P (2015) Gait knee kinematics after ACL reconstruction: 3D assessment. Int Orthop 39:1187–1193

Barenius B, Ponzer S, Shalabi A, Bujak R, Norlén L, Eriksson K (2014) Increased risk of osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 14-year follow-up study of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 42:1049–1057

Tsoukas D, Rotopoulos V, Basdekis G, Makridis KG (2016) No difference in osteoarthritis after surgical and non-surgical treatment of ACL-injured knees after 10 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:2953-2959

Ambra LF, Rezende FC, Xavier B, Shumaker FC, da Silveira Franciozi CE, Luzo MV (2016) Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: how do we perform it? Brazilian orthopaedic surgeons’ preference. Int Orthop 40:595–600

Filardo G, Kon E, Tentoni F, Andriolo L, Di Martino A, Busacca M, Di Matteo B, Marcacci M (2016) Anterior cruciate ligament injury: post-traumatic bone marrow oedema correlates with long-term prognosis. Int Orthop 40:183–190

Risberg MA, Oiestad BE, Gunderson R, Aune AK, Engebretsen L, Culvenor A, Holm I (2016) Changes in knee osteoarthritis, symptoms, and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a 20-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Sports Med 44:1215–1244

Meuffels DE, Favejee MM, Vissers MM, Heijboer MP, Reijman M, Verhaar JAN (2009) Ten year follow-up study comparing conservative versus operative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures. A matched-pair analysis of high level athletes. Br J Sports Med 43:347–351

Streich NA, Zimmermann D, Bode G, Schmitt H (2011) Reconstructive versus non-reconstructive treatment of anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency. A retrospective matched-pair long-term follow-up. Int Orthop 35:607–613

Ramski DE, Kanj WW, Franklin CC, Baldwin KD, Ganley T (2013) Anterior cruciate ligament tears in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis of nonoperative versus operative treatment. Am J Sports Med 42:2769–2776

Lysholm J, Gillquist J (1982) Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 10:150–154

Tegner Y, Lysholm J (1985) Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 198:43–49

Price D, Bush F, Long S, Harkins S (1994) A comparison of pain measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple numerical rating scales. Pain 56:217–226

Roos EM, Lohmander LS (2003) The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1:64

Sherman MF, Warren RF, Marshall JL, Savatsky GJ (1988) A clinical and radiographical analysis of 127 anterior cruciate insufficient knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 227:22–237

Sherman MF, Lieber L, Bonamo JR, Podesta L, Reiter I (1991) The long-term followup of primary anterior cruciate ligament repair. Defining a rationale for augmentation. Am J Sports Med 19:243–255

Fink C, Hoser C, Hackl W, Navarro RA, Benedetto KP (2001) Long-term outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture—is sports activity a determining variable? Int J Sports Med 22:304–309

Delince P, Ghafil D (2012) Anterior cruciate ligament tears: conservative or surgical treatment? A critical review of the literature. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 20:48–61

Filbay SR, Culvenor AG, Ackerman IN, Russel TG, Crossley KM (2015) Quality of life in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 49:1033–1041

Frobell RB, Roos EM, Roos HP, Ranstam J, Lohmander LS (2010) A randomized trial of treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. N Engl J Med 363:331–342

Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, Roemer FW, Ranstam JR, Lohmander LS (2013) Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomized trial. BMJ 346:f232

Kannus P, Jarvinen M (1987) Conservatively treated tears of the anterior cruciate ligament. Long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 69:1007–1012

Barrack RL, Bruckner JD, Kneisl J, Inman WS, Alexander AH (1990) The outcome of nonoperatively treated complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in active young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res 259:192–199

Engstrom B, Gornitzka J, Johansson C, Wredmark T (1993) Knee function after anterior cruciate ligament ruptures treated conservatively. Int Orthop 17:208–213

Spahn G, Schiltenwolf M, Harmann B, Grifka J, Hofmann GO, Klemm HT (2015) The time-related risk for knee osteoarthritis after ACL injury: results from a systematic review. Orthopade 45:81–90

Chalmers PN, Mall NA, Moric M, Sherman SL, Paletta GP, Cole BJ, Bach BR Jr (2014) Does ACL reconstruction alter natural history?: A systematic literature review of long-term outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 96:292–300

Luc B, Gribble PA, Pietrosimone BG (2014) Osteoarthritis prevalence following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review and numbers-needed-to-treat analysis. J Athl Train 49:806–819

Smith TO, Postle K, Penny F, McNamara I, Mann CJ (2014) Is reconstruction the best management stategy for anterior cruciate ligament rupture? A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction versus non-operative treatment. Knee 21:462–470

Harris KP, Driban JB, Sitler MR, Cattano NM, Balasubramanian E (2015) Tibiofemoral osteoarthritis after surgical or nonsurgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review. J Athl Train. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.89

Fithian CD, Paxton EW, Stone ML, Luetzow WF, Csintalan RP, Phelan D, Daniel DM (2005) Prospective trial of a treatment algorithm for the management of the anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Am J Sports Med 33:335–346

Kessler MA, Behrend H, Henz S, Stutz G, Rukavina A, Kuster MS (2008) Function, osteoarthritis and activity after ACL-rupture: 11 years follow-up results of conservative versus reconstructive treatment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 16:442–448

Gille J, Gerlach IJ, Oheim R, Hintze T, Himpe B, Schultz AP (2015) Functional outcome of septic arthritis after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Int Orthop 39:1195–1201

Sanders TL, Kremers HM, Bryan AJ, Kremers WK, Levy BA, Dahm DL, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ (2016) Incidence of and factors associated with the decision to undergo anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction 1 to 10 years after injury. Am J Sports Med 44:1558–1564

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Konrads, C., Reppenhagen, S., Belder, D. et al. Long-term outcome of anterior cruciate ligament tear without reconstruction: a longitudinal prospective study. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 40, 2325–2330 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3294-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-016-3294-0