Abstract

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is an inflammatory process of the pancreas that occurs most commonly in elderly males and clinically can mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma and present with jaundice, weight loss, and abdominal pain. Mass-forming lesions in the pancreas are seen in the focal form of AIP and both clinical and imaging findings can overlap those of pancreatic cancer. The accurate distinction of AIP from pancreatic cancer is of utmost importance as it means avoiding unnecessary surgery in AIP cases or inaccurate steroid treatment in patients with pancreatic cancer. Imaging concomitantly with serological examinations (IgG4 and Ca 19-9) plays an important role in the distinction between these entities. Characteristic extra-pancreatic manifestations as well as favorable good response to treatment with steroids are characteristic of AIP. This paper will review current diagnostic parameters useful in differentiating between focal AIP and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a rare type of chronic pancreatitis that is more commonly seen in males than females and accounts for 2–10% of all chronic pancreatitis [1, 2]. The etiology and pathogenesis of AIP remains unclear [3] but a multifactorial process related to autoimmunity, genetic susceptibility, and exposure to environmental factors is favored [4]. AIP is classified as Type 1 and Type 2 with Type 1 being more common than Type 2. Type 1 is an IgG4-related systemic disease that can have extra-pancreatic involvement. Type 2 histologically demonstrates idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis with the hallmark granulocytic epithelial lesions (GEL) [5]. Type 2 only involves the pancreas [6].

When diffuse involvement is present, autoimmune pancreatitis characteristically appears on cross-sectional imaging as “sausage-like” enlargement of the pancreas. However, AIP can also present as a focal mass-forming pancreatitis, which comprises about 28-41% of cases of autoimmune pancreatitis [7, 8]. It can be difficult to distinguish focal mass-forming AIP from pancreatic adenocarcinoma as imaging as well as clinical characteristics often overlap. However, this differentiation is critical as the management and prognosis vary drastically. AIP is a benign fibroinflammatory disease that responds favorably to corticosteroid therapy (Fig. 1), while pancreatic adenocarcinoma requires surgical resection for a chance for cure. In addition, the overall survival rate for pancreatic adenocarcinoma is 28% after 1 year and 7% after 5 years [9] and surgery can have a 5% mortality and 40–50% morbidity [10].

A 72-year-old male with pancreatic mass incidentally found on chest CT and normal serum IgG4. a Axial unenhanced CT image shows mass-like lesion in the pancreatic body (arrow) prompting further evaluation with MRI. b Axial T1 FS portal venous phase MR image shows an enhancing lesion (arrow), corresponding to finding on chest CT. c Axial unenhanced CT image 8 months after steroid treatment for presumed AIP based on biopsy shows resolution of the mass-like lesion (arrow) in the pancreas consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis

This paper will review diagnostic parameters that assist in the differentiation between mass-forming AIP and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Diagnostic approach

Several diagnostic criteria have been proposed for AIP in an attempt to unify the diagnostic criteria for AIP incorporating clinicopathological and radiological characteristics. These include the original Japanese Pancreas Society guidelines, the Mayo Clinic HISORt (Histology, Imaging, Serology, Other Organ involvement, Response to therapy) criteria and the most recently proposed in 2011 criteria from The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC). The ICDC proposed two forms of AIP on the basis of their histopathological profiles, which are referred to as type I, associated with a histological pattern of lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP), and type II, characterized by idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis (IDCP) [3]. Type 1 is considered a prototype of immunoglobulin 4 (IgG4)-related disease, with high serum levels of IgG4 (> 140 mg/dl), IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration, and sclerosis, while type 2 is related to granulocytic epithelial lesion [3, 6, 11]. Both types can take on various morphologies in the pancreas, which include diffuse, focal/mass-forming, or multifocal disease. While AIP is still rare, the diffuse type is being diagnosed with increasing frequency due to increasing awareness of its pathology [12]. As focal AIP can mimic pancreatic cancer, the distinction can be difficult, however, certain clinical and imaging features can help distinguish the entities and will be discussed.

Clinical

AIP’s clinical presentation can closely mimic cancer. Both entities commonly present with painless obstructive jaundice, reported in up to 70% of patients with AIP [13, 14]. Some studies have suggested that the course of the jaundice associated with cancer may have a steady progression in comparison to the jaundice of AIP that fluctuates or improves spontaneously [15]. While abdominal pain and weight loss are more common in pancreatic cancer [16,17,18], these symptoms can also be seen in patients with AIP. Weight loss is seen in up to one-third of the patients with AIP [2, 19].

Serology

Serum IgG4 levels is a useful diagnostic parameter that can be elevated in cases of AIP. Prior studies have shown that using a cut-off value of 135 mg/dL for serum IgG4 can yield a sensitivity of 65% and a specificity of 98% for diagnosing AIP [20]. However, 7–10% of pancreatic cancer patients exhibit elevated serum IgG4 levels and a significant minority of type I AIP patients may have equivocal serum IgG4 levels [21, 22]. In addition, because of the low prevalence of AIP compared to pancreatic cancer, the positive predictive value of IgG4 for diagnosing AIP is not high, estimated to be near 80% [23], which may limit its utility. Serum CA 19-9 level is the most useful marker for pancreatic cancer with a sensitivity and specificity of 79% and 82%, respectively [24], and is more often elevated in pancreatic cancer than in AIP patients [25]. However, elevated levels of CA19-9 are also seen in other non-malignant conditions, including AIP [26,27,28,29] which can be confounding. CA19-9 also lacks sensitivity for smaller diameter (≤ 2 cm) pancreatic cancers that present the greatest diagnostic challenge in distinguishing cancer from focal AIP [30]. Therefore, elevated CA19-9 cannot be used alone to confidently choose the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in favor of focal AIP. Recent studies have also investigated the utility of serum IgG4 levels in conjunction with CA19-9 levels to distinguish type I AIP from pancreatic cancer [17, 20], which present it as a promising tool for distinguishing the two entities. However, the ideal cut-off parameters and diagnostic performance reported are variable and require further validation with larger studies. A multitude of other serologic markers have been investigated for their potential utility, including levels of total IgG, gamma-globulin, glycosylation profile of IgG [31,32,33,34] carcinoembryonic antigen, and autoantibodies, such as ANA, RF, anti-carbo anhydrase II, and antilactoferrin [35]. Currently, these parameters lack sufficient validation to be of clinical utility.

Histology

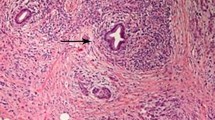

Histologically, the presence of fibrosis and lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the pancreas is considered diagnostic of AIP. In the setting of characteristic imaging findings and elevated IgG4, biopsy is not necessary to confirm the diagnosis of diffuse form of AIP although a response to steroid therapy should be validated. The histologic evaluation of AIP requires an adequate sample size and the preservation of the pancreatic tissue architecture. EUS-guided Tru-Cut core biopsy (TCB) is a suggested way of obtaining samples as it allows for adequate sample sizes and preservation of tissue architecture. This technique has been shown to confirm IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltration in up to 94% of patients with AIP [21]. Although EUS-FNA is relatively accurate for the cytologic diagnosis of pancreatic cancer [36,37,38], EUS-FNA is less accurate for AIP as it lacks any specific cytologic findings. In addition, due to the smaller caliber of the needle, the resulting tissue architecture is often compromised and the sample size inadequate [39, 40]. Histologic findings that confirm AIP may be either periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with obliterative phlebitis and storiform fibrosis or lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with storiform fibrosis and 10 or greater IgG4 cells/HPF.

Extra-pancreatic lesions

AIP demonstrates a variety of extra-pancreatic manifestations with 92% of cases showing simultaneous pancreatic and extra-pancreatic lesions [41]. The presence of extra-pancreatic involvement can assist in distinguishing focal AIP from pancreatic cancer. Type 1 AIP is typically associated with extra-pancreatic findings, whereas type 2 is not, although type 2 AIP is associated with inflammatory bowel disease, especially ulcerative colitis [42]. The most commonly affected extra-pancreatic sites in AIP are the biliary tree (68-88% of patients) [43], kidneys (35% of patients), retroperitoneum (10–20% of patients) [44, 45], and salivary/lacrimal glands (12–16% of patients) [43]. Biliary tract involvement, also known as an IgG4 sclerosing type cholangitis, typically involves the distal common duct resulting in stricturing of the distal duct but can also present with multifocal intra- and extra-hepatic strictures similar in appearance to primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gallbladder involvement may also be present manifesting as wall thickening. Renal involvement presents as focal lesions secondary to tubulointerstitial nephritis [44]. Retroperitoneal fibrosis, salivary/lacrimal gland involvement, lymph node involvement, and interstitial pneumonitis have also been associated with AIP. The extra-pancreatic involvement in AIP does not have the typical appearance of metastatic disease from pancreatic cancer, and when present, these findings can aid in distinguishing focal AIP from pancreatic cancer.

Symptoms related to these extra-pancreatic lesions also often improve with steroid treatment and can be useful for the evaluation of treatment response. These lesions may also have implications regarding AIP relapse, with Naitoh et al. reporting that diffuse pancreatic ductal changes and sclerosing sialadenitis at clinical onset were independent predictors of relapse [46].

Imaging: pancreatic findings

Computed tomography (CT)

CT is a commonly used imaging modality when evaluating for pancreatic pathology. The classic imaging appearance of AIP with diffuse pancreatic involvement includes diffuse sausage-like pancreatic enlargement and a symmetric rim of low attenuation surrounding the pancreas (Fig. 2) that is considered to be characteristic of AIP [47].

A 56-year-old female with elevated lipase and normal serum IgG4. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows a diffusely enlarged (“sausage shape”), homogeneously enhancing pancreas (arrows). A subtle low attenuation rim is seen around the periphery of the pancreas. The patient was treated with corticosteroids based on clinical judgment and characteristic imaging findings with resolution of the patient’s imaging findings consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis

The diagnosis of focal AIP can be more challenging based on imaging and difficult to distinguish from pancreatic cancer. Focal AIP is associated with focal mass-like enlargement of a portion of the pancreas, usually the head and/or uncinate process, and, similar to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, appears hypoattenuating in the early arterial phase of enhancement [48]. A study by Takahashi et al. showed focal AIP to demonstrate increased enhancement compared to pancreatic cancer on the portal venous phase of imaging (12). In distinction to pancreatic cancer, some imaging findings have been noted to be more associated with focal AIP. These include delayed homogeneous enhancement on dynamic CT (Fig. 3) [7, 10, 16, 18, 47, 49,50,51], a hypoattenuating capsule-like rim [7, 16, 18, 47, 51, 52], absence of atrophic changes in the body and tail of the pancreas [7, 16], absence of significant upstream main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation (> 5 mm) [51,52,53], the presence of the “duct-penetrating” sign (mass penetrated by an unobstructed pancreatic duct), and enhanced duct sign (wall enhancement of MPD in the lesion) on multiphase contrast-enhanced CT [47].

A 64-year-old male with elevated liver test function and status post biliary stent placement. a Axial unenhanced CT image shows focal enlargement of the pancreatic head (arrows). b Axial arterial phase contrast-enhanced CT and c delayed phase shows progressive enhancement of the lesion in the pancreatic head (arrows). Pathology yielded lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis

Pancreatic cancer most commonly occurs in the pancreatic head (60–70%) [54]. On CT, adenocarcinoma typically appears as a hypodense mass that may result in pancreatic ductal dilatation and biliary dilatation (double duct sign) [10, 52, 53], abrupt termination of the involved duct, upstream pancreatic atrophy [53], and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy [51]. Vascular involvement (Fig. 4) manifesting as caliber change, irregularity to the vessel walls, and tumoral encasement of more than 180° of vessel circumference, as well as peritumoral fat infiltration is also important for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and determining appropriate therapy [55].

A 43-year-old male with pancreatic mass. a Axial contrast-enhanced arterial phase CT image shows a hypoenhancing pancreatic neck mass (arrow) abutting the anterior aspect of the superior mesenteric artery. b Axial contrast-enhanced venous phase CT image shows narrowing of the splenic vein at the level of portal confluence (arrow) and dilatation of the pancreatic duct. c Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image shows the mass encasing the superior mesenteric vein (arrow). This lesion was biopsy-proven pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Follow-up imaging is important to distinguish AIP from other diseases as a lack of response following 2–4-week course of steroid therapy suggests an alternative diagnosis including adenocarcinoma [56].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI of AIP shows similar morphologic findings as CT including focal (or diffuse or multifocal, depending on the pattern) enlargement of the pancreas. The involved area is hypointense on T1-weighted images, and slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 5). Some authors have described a “speckled” enhancement pattern in the pancreatic phase of imaging as more characteristic of focal AIP than pancreatic cancer [57]. The “duct-penetrating” sign [7, 58,59,60], best appreciated using secretin-enhanced MRCP [61], is more characteristic of focal AIP than pancreatic cancer. This is believed to be a result of the inflammatory nature of AIP being more apt to narrow the main pancreatic duct as opposed to pancreatic cancer obstructing the duct [44]. The degree of dilatation involving the MPD (Fig. 6) is less in focal AIP and are usually limited to < 4 mm as opposed to pancreatic cancers, which usually cause ≥ 4 mm dilatation [7, 18, 49, 58, 62]. Irregular narrowing of the MPD is typical of AIP [44] and may be better visualized on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), due to the inferior resolution of MRCP when compared to ERCP [63]. In addition, focal AIP more frequently shows a longer length of narrowing of MPD (3 cm or more in length) [62] in the involved segment of the pancreas [18, 49], as well as the “icicle sign” (smooth tapered narrowing of the upstream pancreatic duct) (Fig. 6) [53, 60]. At MRCP, multiple strictures of the MPD may be a useful sign of focal AIP, with a reported prevalence of 61.5% of these multifocal strictures along the whole extension of the MPD even if the parenchymal changes were segmental [64]. Additional MR findings seen more frequently with AIP include delayed homogeneous enhancement of the lesion (Figs. 5 and 6) [7, 59] and a hypointense capsule-like rim [7, 59,60,61].

A 29-year-old male with history of recurrent pancreatitis, elevated lipase, and normal serum IgG4. a Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a mildly hyperintense lesion in the uncinate process of the pancreas (arrow). b Axial unenhanced T1 FS MR image shows the lesion to be hypointense (arrow). c Axial T1 FS contrast-enhanced MR arterial phase image shows hypoenhancing lesion (arrow) and d delayed phase image shows progressive enhancement (arrow). e Diffusion-weighted axial MR image (b500 s/mm2) shows increased signal and f low signal on ADC map from restricted diffusion (arrow). After a trial of corticosteroid treatment, based on clinical judgment, the patient’s symptoms and imaging findings resolved which suggested autoimmune pancreatitis

A 62-year-old man with obstructive jaundice, post placement of an indwelling biliary stent, elevated CA19-9 and IgG4. a Axial T2-weighted MR image shows heterogeneous lesion in the pancreatic head (arrow). b Axial T2-weighted MR image shows mild pancreatic duct dilatation (arrow) the degree to which is at a lesser extent than typical for a pancreatic adenocarcinoma. c MRCP images show smooth tapered narrowing of the upstream pancreatic duct mimicking an icicle or ice pick (“icicle sign”). d Axial unenhanced T1 FS MR image shows a heterogeneous lesion in the pancreatic head. e Axial arterial phase T1 FS contrast-enhanced MR images shows heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion (arrow) and f delayed phase shows progressive homogeneous enhancement (arrow). Patient underwent a Whipple procedure because of suspicion of malignancy but pathology yielded lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing (autoimmune) pancreatitis

As on CT, pancreatic cancer on MR is more likely than AIP to show a mass with associated peripancreatic infiltration and vascular encasement, upstream pancreatic atrophy, and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy [58].

Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) has been increasingly utilized in abdominal imaging to assess for pathology. On DWI, both AIP and pancreatic cancer show high signal intensity areas at high b values [15] AIP presents as high signal intensity areas with a diffuse, solitary, and multiple pattern, whereas pancreatic cancer typically has a solitary high signal intensity areas. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was significantly lower in AIP than pancreatic cancers or normal pancreas [7, 15, 58, 59]. Different ADC optimal cut-off values have been reported in the literature to try to distinguish focal AIP from pancreatic cancer, ranging from 0.88 to 1.26 × 10−3 mm2/s [7, 15, 58, 59].

Ultrasonography (US)

Conventional US may be the first imaging modality performed in the presence of abdominal symptoms especially right upper quadrant pain. The distinction of pancreatic cancer from focal AIP on ultrasonography is exceedingly difficult as they both present as hypoechoic masses.

Positron emission tomography- computed tomography (PET-CT)

Due to the concern for pancreatic cancer based on clinical and/or imaging findings, patients who are ultimately diagnosed with AIP may undergo fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) after initial cross-sectional imaging (Fig. 7). Studies have shown that AIP presents with lower FDG activity when compared to pancreatic cancer, with both early and delayed maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) being higher in pancreatic cancers [65]. Lee et al. observed that 53% of AIP had diffuse uptake of FDG compared to 3% in pancreatic cancer [66]. In the pancreatic cancer cases, the high uptake was because of obstructive pancreatitis, which could be distinguished by other CT characteristics. In another study, heterogeneous FDG uptake was mostly found in AIP cases while pancreatic cases show homogeneous uptake [67]. PET/CT has also been used to assess response to steroid therapy with decreased uptake in the pancreas and extra-pancreatic locations following therapy [66].

A 79-year-old female with a history of breast and lung cancer with normal serum IgG4 and elevated CA19-9. a Axial unenhanced CT image shows focal enlargement of the pancreatic tail (arrow). b Axial contrast-enhanced arterial and c venous phase CT image shows progressive enhancement of the pancreatic tail lesion on the venous phase (arrow). d Axial PET/CT images show hypermetabolic activity in the pancreatic tail lesion. Pathology after surgical resection yielded autoimmune pancreatitis as biopsy was not definitive

Novel imaging techniques

MR elastography has been recently evaluated to facilitate differentiation between AIP and pancreatic cancer with a recent study showing pancreatic stiffness was significantly lower in AIP (2.67 kPa) when compared to pancreatic cancer (3.78 kPa). However, the clinical relevance of MRE to distinguish focal AIP from pancreatic adenocarcinoma and stage AIP has yet to be determined.

The role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) to distinguish focal AIP from pancreatic cancer (27–29) is also an emerging technology. A recent study demonstrated hyper- to iso-enhancement in the arterial phase, homogeneous contrast distribution, and absent irregular internal vessels observed more frequently in focal AIP than in pancreatic cancer [68]. These authors concluded that CEUS may be a valuable non-invasive tool in the differential diagnosis of focal AIP and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [68]. However, further investigation is warranted to determine the role CEUS may play in distinguishing the two entities.

Imaging: extra-pancreatic findings

Radiologic recognition of the extra-pancreatic manifestations of AIP is paramount as they can be critical to the diagnosis of AIP when pancreatic features are atypical and the distinction from pancreatic cancer is difficult [44]. Extra-pancreatic findings of AIP differ from the typical location and appearance of metastatic pancreatic cancer and can help in the distinction between the two entities. Pancreatic metastases occur primarily to the liver (Fig. 8), lungs [54], peritoneum and omentum, and lymph nodes [69], whereas extra-pancreatic involvement of AIP most commonly involves the biliary tree, kidneys, retroperitoneum, and salivary/lacrimal glands.

A 69-year-old female with a history of follicular lymphoma and elevated liver function tests. a Axial T1 FS MR image shows a hypointense mass in the pancreatic tail (arrow). b Diffusion-weighted MR image (b800 s/mm2) and c ADC map show restricted diffusion of the mass (arrow). d Axial T1 FS arterial phase MR image shows multiple hepatic masses with peripheral enhancement and central hypo-enhancement (arrow) characteristic of metastases (arrow on a representative metastasis). e Diffusion-weighted axial MR image (b800 s/mm2) and f ADC map show restricted diffusion of the hepatic lesions (arrow on a representative metastasis). Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of hepatic metastases from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Biliary involvement of AIP is most commonly characterized by a long segment stricture with pre-stenotic dilatation of the distal common bile duct (Fig. 9) [44]. Multifocal strictures or thickening of the intra- or extra-hepatic bile duct (10–35% of patients), resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis, can also be present. Gallbladder involvement appears as diffuse mural thickening [44], and decreased signal intensity on T2-weighted images as well as delayed contrast enhancement [45].

A 78-year-old male with history of jaundice, normal serum IgG4 and Ca19-9. a ERCP image shows a beaded appearance to the intrahepatic biliary tree with multifocal areas of strictures and intrahepatic biliary dilatation. Stricture of the common bile duct is also present (arrow). b MRCP image status post ERCP with balloon dilatation of the common bile duct shows persistent intrahepatic biliary dilatation with multifocal strictures (arrow) and resolution of the common bile duct stricture. Mild prominence of pancreatic duct (arrowhead) is also present. c EUS image shows a pancreatic head mass (calipers). Biopsy of the pancreatic head mass confirmed the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis with histiocytic and plasma cell infiltrate

Renal involvement, primarily occurring in the renal cortex, appears on MRI as iso- or hypointense lesions on T1- and hypointense lesions on T2-weighted images with gradual enhancement on contrast-enhanced images [44, 45, 70] and restricted diffusion (Fig. 10) [45]. On CT, renal lesions appear hypoattenuating on early-phase contrast-enhanced imaging, with gradual enhancement on delayed phases [70]. Gallium-67 scintigraphy shows increased uptake in the involved renal lesions [41].

A 30-year-old female with a pancreatic mass seen during a prenatal ultrasound and normal serum IgG4. a Axial T1-weighted FS image shows T1 hypointense lesions in the pancreatic body and tail. b Axial T1-weighted FS delayed contrast-enhanced image shows that lesions are hyperenhancing relative to the pancreas. c Diffusion-weighted MR images (b800 s/mm2) show subtle focal lesions within the renal medulla with increased signal intensity (arrows). The patient was treated for suspected autoimmune pancreatitis with corticosteroids, based on clinical judgment. Post steroid treatment (six months later) axial T1-weighted FS delayed contrast-enhanced image shows resolution of the lesions of the pancreatic body and tail representing response to treatment. The renal lesions also resolved (not shown)

In the retroperitoneum, findings suggestive of retroperitoneal fibrosis include a characteristic fibrotic mass around the aorta or inferior vena cava (Fig. 11). Entrapment of the ureters resulting in hydronephrosis can occur [44, 45]. Sonographically, retroperitoneal fibrosis appears as a retroperitoneal hypoechoic soft-tissue lesion. MR shows a low or intermediate signal intensity lesion on T1-weighted images, variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and variable contrast enhancement [70].

A 62-year-old male with a history of common bile duct stent placement. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT and b T1 FS contrast-enhanced MR images show circumferential soft tissue surrounding the aorta (arrow) compatible with retroperitoneal fibrosis associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. c Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows a diffusely enlarged, homogeneously enhancing pancreas with hypodense rim (arrows). After a trial of corticosteroid treatment, based on clinical judgment, the patient’s imaging findings resolved which suggested autoimmune pancreatitis

Salivary and lacrimal glands involvement are seen as an enlargement of the glands and may lead to Mikulicz disease or Kuttner tumor. In Mikulicz disease, bilateral swelling of the involved glands with MR show homogeneous T1 and T2 hypointense lesions that show enhancement on contrast-enhanced sequences. Kuttner disease is a chronic sclerosing sialadenitis that results in a non-neoplastic lesion that on MR is isointense on T1-weighted images, hypointense on T2-weighted images, and enhances homogeneously [45].

IgG4-related prostatitis has been reported to have a prevalence of 10% with the prostate appearing diffusely enlarged with low attenuation and surrounding inflammatory stranding [48]. At DWI, the prostate showed swelling with high signal intensities, mimicking prostatitis and prostate cancer [41].

On PET scans, both pancreatic cancer and AIP show extra-pancreatic FDG uptake; however, increased uptake in the kidney and salivary gland has been shown to be seen only in AIP cases [66]. Unlike pancreatic cancer, AIP more often has increased FDG activity of the extra-pancreatic portion of the bile duct, higher SUV max for the prostate gland, and slower liver clearance of FDG activity, with FDG retention index values of 1.8% for AIP and 6.7% for pancreatic cancer [65]. A simultaneous finding of diffuse pancreatic FDG uptake and increased inverted “V”-shaped FDG uptake in the prostate was observed only in AIP cases according to Zhang et al. [65].

Conclusion

Differentiating focal AIP from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma poses a diagnostic challenge as there is clinical and radiological overlap. It is essential for the radiologist to be knowledgeable of the imaging features that are suggestive of focal AIP over pancreatic ductal carcinoma as the treatment between and prognosis of the two entities varies greatly. Features that are suggestive of focal AIP over pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma include delayed homogeneous enhancement, hypointense/hypodense capsule-like rim, absence of pancreatic atrophic changes, “duct penetrating” sign, irregular narrowing of the MPD and extra-pancreatic manifestations (most commonly the biliary tract and renal involvement), and excellent response to steroid treatment. Findings favoring pancreatic adenocarcinoma, though not specific, include “double duct” sign, abrupt duct cut-off, pancreatic atrophy, vascular encasement, and the presence of metastases to common sites, most typically the liver. Though imaging and clinical parameters can be suggestive of one particular entity, in many cases biopsy is still needed for diagnosis.

References

Cao Z, Tian R, Zhang T, Zhao Y (2015) Localized autoimmune pancreatitis: report of a case clinically mimicking pancreatic cancer and a literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 94 (42):e1656. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000001656

Kim KP, Kim MH, Song MH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK (2004) Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 99 (8):1605-1616. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30336.x

Hoshimoto S, Aiura K, Tanaka M, Shito M, Kakefuda T, Sugiura H (2016) Mass-forming type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis mimicking pancreatic cancer. J Dig Dis 17 (3):202-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-2980.12316

Hart PA, Zen Y, Chari ST (2015) Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 149 (1):39-51. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.010

Madhani K, Farrell JJ (2016) Autoimmune pancreatitis: an update on diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 45 (1):29-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2015.10.005

Khandelwal A, Shanbhogue AK, Takahashi N, Sandrasegaran K, Prasad SR (2014) Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of autoimmune pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 202 (5):1007-1021. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.13.11247

Muhi A, Ichikawa T, Motosugi U, Sou H, Sano K, Tsukamoto T, Fatima Z, Araki T (2012) Mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma: differential diagnosis on the basis of computed tomography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, and diffusion-weighted imaging findings. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI 35 (4):827-836. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22881

Al-Hawary MM, Kaza RK, Azar SF, Ruma JA, Francis IR (2013) Mimics of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Imaging 13 (3):342-349. https://doi.org/10.1102/1470-7330.2013.9012

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2017) Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 67 (1):7-30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21387

Lee H, Lee JK, Kang SS, Choi D, Jang KT, Kim JH, Lee KT, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Rhee JC (2007) Is there any clinical or radiologic feature as a preoperative marker for differentiating mass-forming pancreatitis from early-stage pancreatic adenocarcinoma? Hepatogastroenterology 54 (79):2134-2140

de Pretis N, Amodio A, Frulloni L (2018) Updates in the field of autoimmune pancreatitis: a clinical guide. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 12 (7):705-709. https://doi.org/10.1080/17474124.2018.1489230

Sugumar A, Chari ST (2009) Distinguishing pancreatic cancer from autoimmune pancreatitis: a comparison of two strategies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7 (11 Suppl):S59-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.07.034

Church NI, Pereira SP, Deheragoda MG, Sandanayake N, Amin Z, Lees WR, Gillams A, Rodriguez-Justo M, Novelli M, Seward EW, Hatfield AR, Webster GJ (2007) Autoimmune pancreatitis: clinical and radiological features and objective response to steroid therapy in a UK series. Am J Gastroenterol 102 (11):2417-2425. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01531.x

Notohara K, Burgart LJ, Yadav D, Chari S, Smyrk TC (2003) Idiopathic chronic pancreatitis with periductal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration: clinicopathologic features of 35 cases. The American journal of surgical pathology 27 (8):1119-1127

Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Hata T, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K, Suzuki M, Kamata N, Sasaki T (2010) Differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer by diffusion-weighted MRI. Am J Gastroenterol 105 (8):1870-1875. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.87

Kamisawa T, Imai M, Yui Chen P, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Suzuki M, Kamata N (2008) Strategy for differentiating autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 37 (3):e62-67. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0b013e318175e3a0

Chang MC, Liang PC, Jan S, Yang CY, Tien YW, Wei SC, Wong JM, Chang YT (2014) Increase diagnostic accuracy in differentiating focal type autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer with combined serum IgG4 and CA19-9 levels. Pancreatology: official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) [et al] 14 (5):366-372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pan.2014.07.010

Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Hayashi K, Okumura F, Miyabe K, Shimizu S, Kondo H, Yoshida M, Yamashita H, Ohara H, Joh T (2012) Clinical differences between mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol 47 (5):607-613. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365521.2012.667147

Finkelberg DL, Sahani D, Deshpande V, Brugge WR (2006) Autoimmune pancreatitis. The New England journal of medicine 355 (25):2670-2676. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmra061200

van Heerde MJ, Buijs J, Hansen BE, de Waart M, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Pek CJ, Poley JW, Bruno MJ, Kuipers EJ, van Buuren HR (2014) Serum level of Ca 19-9 increases ability of IgG4 test to distinguish patients with autoimmune pancreatitis from those with pancreatic carcinoma. Digestive diseases and sciences 59 (6):1322-1329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-013-3004-3

Ghazale A, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Pelaez-Luna M, Petersen BT, Vege SS, Farnell MB (2007) Value of serum IgG4 in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis and in distinguishing it from pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 102 (8):1646-1653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01264.x

Raina A, Krasinskas AM, Greer JB, Lamb J, Fink E, Moser AJ, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Slivka A, Whitcomb DC (2008) Serum immunoglobulin G fraction 4 levels in pancreatic cancer: elevations not associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 132 (1):48-53. https://doi.org/10.1043/1543-2165(2008)132%5b48:sigfli%5d2.0.co;2

Pak LM, Schattner MA, Balachandran V, D’Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Kingham TP, Jarnagin WR, Allen PJ (2018) The clinical utility of immunoglobulin G4 in the evaluation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. HPB: the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association 20 (2):182-187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpb.2017.09.001

Goonetilleke KS, Siriwardena AK (2007) Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 33 (3):266-270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2006.10.004

Chari ST, Takahashi N, Levy MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MA, Vege SS (2009) A diagnostic strategy to distinguish autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7 (10):1097-1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.020

Parra JL, Kaplan S, Barkin JS (2005) Elevated CA 19-9 caused by Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: review of the benign causes of increased CA 19-9 level. Digestive diseases and sciences 50 (4):694-695

Kodama T, Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Ohtsuka M (2007) Serum levels of CA19-9 in patients with nonmalignant respiratory diseases. Journal of clinical laboratory analysis 21 (2):103-106. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.20136

Kim HR, Lee CH, Kim YW, Han SK, Shim YS, Yim JJ (2009) Increased CA 19-9 level in patients without malignant disease. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine 47 (6):750-754. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2009.152

La Greca G, Sofia M, Lombardo R, Latteri S, Ricotta A, Puleo S, Russello D (2012) Adjusting CA19-9 values to predict malignancy in obstructive jaundice: influence of bilirubin and C-reactive protein. World journal of gastroenterology 18 (31):4150-4155. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4150

Steinberg W (1990) The clinical utility of the CA 19-9 tumor-associated antigen. Am J Gastroenterol 85 (4):350-355

Jefferis R (2005) Glycosylation of recombinant antibody therapeutics. Biotechnology progress 21 (1):11-16. https://doi.org/10.1021/bp040016j

Arnold JN, Wormald MR, Sim RB, Rudd PM, Dwek RA (2007) The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annual review of immunology 25:21-50. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702

Dall’Olio F, Vanhooren V, Chen CC, Slagboom PE, Wuhrer M, Franceschi C (2013) N-glycomic biomarkers of biological aging and longevity: a link with inflammaging. Ageing research reviews 12 (2):685-698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2012.02.002

Chen G, Li H, Qiu L, Qin X, Liu H, Li Z (2014) Change of fucosylated IgG2 Fc-glycoforms in pancreatitis and pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a promising disease-classification model. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 406 (1):267-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-013-7439-3

Smyk DS, Rigopoulou EI, Koutsoumpas AL, Kriese S, Burroughs AK, Bogdanos DP (2012) Autoantibodies in autoimmune pancreatitis. International journal of rheumatology 2012:940831. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/940831

Savides TJ, Donohue M, Hunt G, Al-Haddad M, Aslanian H, Ben-Menachem T, Chen VK, Coyle W, Deutsch J, DeWitt J, Dhawan M, Eckardt A, Eloubeidi M, Esker A, Gordon SR, Gress F, Ikenberry S, Joyce AM, Klapman J, Lo S, Maluf-Filho F, Nickl N, Singh V, Wills J, Behling C (2007) EUS-guided FNA diagnostic yield of malignancy in solid pancreatic masses: a benchmark for quality performance measurement. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 66 (2):277-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.017

Gress F, Gottlieb K, Sherman S, Lehman G (2001) Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy of suspected pancreatic cancer. Annals of internal medicine 134 (6):459-464

Fritscher-Ravens A, Brand L, Knofel WT, Bobrowski C, Topalidis T, Thonke F, de Werth A, Soehendra N (2002) Comparison of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for focal pancreatic lesions in patients with normal parenchyma and chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 97 (11):2768-2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.07020.x

Wiersema MJ, Levy MJ, Harewood GC, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Jondal ML, Wiersema LM (2002) Initial experience with EUS-guided trucut needle biopsies of perigastric organs. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 56 (2):275-278

Levy MJ, Jondal ML, Clain J, Wiersema MJ (2003) Preliminary experience with an EUS-guided trucut biopsy needle compared with EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointestinal endoscopy 57 (1):101-106. https://doi.org/10.1067/mge.2003.49

Fujinaga Y, Kadoya M, Kawa S, Hamano H, Ueda K, Momose M, Kawakami S, Yamazaki S, Hatta T, Sugiyama Y (2010) Characteristic findings in images of extra-pancreatic lesions associated with autoimmune pancreatitis. Eur J Radiol 76 (2):228-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.06.010

Kamisawa T, Chari ST, Lerch MM, Kim MH, Gress TM, Shimosegawa T (2013) Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis: type 1 and type 2. Gut 62 (9):1373-1380. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304224

Manfredi R, Frulloni L, Mantovani W, Bonatti M, Graziani R, Pozzi Mucelli R (2011) Autoimmune pancreatitis: pancreatic and extrapancreatic MR imaging-MR cholangiopancreatography findings at diagnosis, after steroid therapy, and at recurrence. Radiology 260 (2):428-436. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11101729

Agrawal S, Daruwala C, Khurana J (2012) Distinguishing autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreaticobiliary cancers: current strategy. Ann Surg 255 (2):248-258. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3182324549

Hafezi-Nejad N, Singh VK, Fung C, Takahashi N, Zaheer A (2018) MR imaging of autoimmune pancreatitis. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 26 (3):463-478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mric.2018.03.008

Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Ando T, Hayashi K, Tanaka H, Okumura F, Miyabe K, Yoshida M, Sano H, Takada H, Joh T (2010) Clinical significance of extrapancreatic lesions in autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreas 39 (1):e1-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0b013e3181bd64a1

Furuhashi N, Suzuki K, Sakurai Y, Ikeda M, Kawai Y, Naganawa S (2015) Differentiation of focal-type autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic carcinoma: assessment by multiphase contrast-enhanced CT. Eur Radiol 25 (5):1366-1374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-014-3512-3

Kozoriz MG, Chandler TM, Patel R, Zwirewich CV, Harris AC (2015) Pancreatic and extrapancreatic features in autoimmune pancreatitis. Can Assoc Radiol J 66 (3):252-258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carj.2014.10.001

Wakabayashi T, Kawaura Y, Satomura Y, Watanabe H, Motoo Y, Okai T, Sawabu N (2003) Clinical and imaging features of autoimmune pancreatitis with focal pancreatic swelling or mass formation: comparison with so-called tumor-forming pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 98 (12):2679-2687. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08727.x

Takahashi N, Fletcher JG, Hough DM, Fidler JL, Kawashima A, Mandrekar JN, Chari ST (2009) Autoimmune pancreatitis: differentiation from pancreatic carcinoma and normal pancreas on the basis of enhancement characteristics at dual-phase CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 193 (2):479-484. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.08.1883

Sun GF, Zuo CJ, Shao CW, Wang JH, Zhang J (2013) Focal autoimmune pancreatitis: radiological characteristics help to distinguish from pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 19 (23):3634-3641. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3634

Lee-Felker SA, Felker ER, Kadell B, Farrell J, Raman SS, Sayre J, Lu DS (2015) Use of MDCT to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from ductal adenocarcinoma and interstitial pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205 (1):2-9. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.14.14059

Chang WI, Kim BJ, Lee JK, Kang P, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Jang KT, Choi SH, Choi DW, Choi DI, Lim JH (2009) The clinical and radiological characteristics of focal mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis: comparison with chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 38 (4):401-408. https://doi.org/10.1097/mpa.0b013e31818d92c0

Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N (2014) Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 371 (22):2140-2141. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc1412266

Al-Hawary MM, Francis IR, Chari ST, Fishman EK, Hough DM, Lu DS, Macari M, Megibow AJ, Miller FH, Mortele KJ, Merchant NB, Minter RM, Tamm EP, Sahani DV, Simeone DM (2014) Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma radiology reporting template: consensus statement of the Society of Abdominal Radiology and the American Pancreatic Association. Radiology 270 (1):248-260. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13131184

Gardner TB, Chari ST (2008) Autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 37 (2):439-460, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2008.02.004

Sugiyama Y, Fujinaga Y, Kadoya M, Ueda K, Kurozumi M, Hamano H, Kawa S (2012) Characteristic magnetic resonance features of focal autoimmune pancreatitis useful for differentiation from pancreatic cancer. Jpn J Radiol 30 (4):296-309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-011-0047-2

Hur BY, Lee JM, Lee JE, Park JY, Kim SJ, Joo I, Shin CI, Baek JH, Kim JH, Han JK, Choi BI (2012) Magnetic resonance imaging findings of the mass-forming type of autoimmune pancreatitis: comparison with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI 36 (1):188-197. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.23609

Choi SY, Kim SH, Kang TW, Song KD, Park HJ, Choi YH (2016) Differentiating mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma on the basis of contrast-enhanced MRI and DWI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 206 (2):291-300. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.15.14974

Kim HJ, Kim YK, Jeong WK, Lee WJ, Choi D (2015) Pancreatic duct “icicle sign” on MRI for distinguishing autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in the proximal pancreas. Eur Radiol 25 (6):1551-1560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-014-3548-4

Carbognin G, Girardi V, Biasiutti C, Camera L, Manfredi R, Frulloni L, Hermans JJ, Mucelli RP (2009) Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging findings on contrast-enhanced MR, MRCP and dynamic secretin-enhanced MRCP. Radiol Med 114 (8):1214-1231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-009-0452-0

Nishino T, Oyama H, Toki F, Shiratori K (2010) Differentiation between autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma based on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography findings. J Gastroenterol 45 (9):988-996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-010-0250-4

Kamisawa T, Tu Y, Egawa N, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kodama M, Kamata N (2009) Can MRCP replace ERCP for the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis? Abdom Imaging 34 (3):381-384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-008-9401-y

Negrelli R, Manfredi R, Pedrinolla B, Boninsegna E, Ventriglia A, Mehrabi S, Frulloni L, Pozzi Mucelli R (2015) Pancreatic duct abnormalities in focal autoimmune pancreatitis: MR/MRCP imaging findings. Eur Radiol 25 (2):359-367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-014-3371-y

Zhang J, Jia G, Zuo C, Jia N, Wang H (2017) (18)F- FDG PET/CT helps differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer 17 (1):695. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3665-y

Lee TY, Kim MH, Park DH, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim JS, Lee KT (2009) Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT for differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis with atypical pancreatic imaging findings from pancreatic cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 193 (2):343-348. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.08.2297

Ozaki Y, Oguchi K, Hamano H, Arakura N, Muraki T, Kiyosawa K, Momose M, Kadoya M, Miyata K, Aizawa T, Kawa S (2008) Differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis from suspected pancreatic cancer by fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Gastroenterol 43 (2):144-151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-007-2132-y

Cho MK, Moon SH, Song TJ, Kim RE, Oh DW, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH (2018) Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for differentially diagnosing autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gut Liver 12 (5):591-596. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl17391

Miller FH, Rini NJ, Keppke AL (2006) MRI of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 187 (4):W365-374. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.05.0875

Vlachou PA, Khalili K, Jang HJ, Fischer S, Hirschfield GM, Kim TK (2011) IgG4-related sclerosing disease: autoimmune pancreatitis and extrapancreatic manifestations. Radiographics 31 (5):1379-1402. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.315105735

Funding

No funding or grant support was used in the preparing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lopes Vendrami, C., Shin, J.S., Hammond, N.A. et al. Differentiation of focal autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Abdom Radiol 45, 1371–1386 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02210-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-02210-0