Abstract

Depth is used often as a proxy for gradients in energetic resources on coral reefs and for predicting patterns of community energy use. With increasing depth, loss of light can lead to a reduced reliance on autotrophy and an increased reliance on heterotrophy by mixotrophic corals. However, the generality of such trophic zonation varies across contexts. By combining high-resolution oceanographic measurements with isotopic analyses (δ13C, δ15N) of multiple producer and consumer levels across depths (10–30 m) at a central Pacific oceanic atoll, we show trophic zonation in mixotrophic corals can be both present and absent within the same reef system. Deep-water internal waves that deliver cool particulate-rich waters to shallow reefs occurred across all sites (2.5–5.6 events week−1 at 30 m) but the majority of events remained depth-restricted (4.3–9.7% recorded at 30 m propagated to 10 m). In the absence of other particulate delivery, mixotrophs increased their relative degree of heterotrophy with increasing depth. However, where relatively long-lasting downwelling events (1.4–3.3 times the duration of any other site) occurred simultaneously, mixotrophs displayed elevated and consistent degrees of heterotrophy regardless of depth. Importantly, these long-lasting surface pulses were of a lagoonal origin, an area of rich heterotrophic resource supply. Under such circumstances, we hypothesize heterotrophic resource abundance loses its direct linkage with depth and, with resources readily available at all depths, trophic zonation is no longer present. Our results show that fine-scale intra-island hydrographic regimes and hydrodynamic connectivity between reef habitats contribute to explaining the context specific nature of coral trophic depth zonation in shallow reef ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mixotrophic corals derive energy through both autotrophic and heterotrophic pathways, allowing them to live in nutrient-poor, oligotrophic waters (Muscatine and Porter 1977). In shallow reef communities where there is an abundance of light, the coral’s photosynthetic symbiotic dinoflagellates of the genus Symbiodinium (hereafter endosymbiont) often provide the majority of the corals daily energetic requirements (Davies 1991). However, with increasing depth, light availability reduces rapidly due to attenuation by the water column. Concurrently a second energetic resource typically becomes more abundant. With increasing depth, the availability of heterotrophic energetic subsidies such as zooplankton and particulate organic matter increases due to vertical gradients in planktonic biomass (Hamner et al. 1988; Genin et al. 2005) and the delivery of sub-thermocline particulate-rich waters by current-driven upwelling (Gove et al. 2006) and internal waves (Leichter et al. 1996). Internal waves are a common feature on many coral reef systems, including coastal reefs in Florida (Leichter et al. 2006), low-lying offshore islands such as those in the Andaman Sea (Roder et al. 2010), high-islands such as Oahu in the north Pacific (Sevadjian et al. 2012) and Moorea in the South Pacific (Leichter et al. 2012), and at isolated oceanic atolls, such as Palmyra Atoll in the central Pacific (Gove et al. 2015). Subsidies delivered via these physical mechanisms often are stratified vertically across coral reef environments as the passive movement of small particles result in spatial patterning across water density gradients established by temperature stratification (Genin et al. 2009; Monismith et al. 2010; Wyatt et al. 2012, 2013).

Resource stratification across depths in shallow reef communities commonly results in pronounced zonation in organisms with inflexible trophic strategies. For example, the abundance of obligate heterotrophs such as planktivorous fishes can increase with depth, associated with greater proximity to sources of zooplankton (Friedlander et al. 2010). In contrast, obligate autotrophs such as fleshy macroalgae can decrease in abundance with increasing depth due to reduced light availability (Williams et al. 2013). However, the trophic plasticity of some mixotrophic corals (Palardy et al. 2008) allows them to persist across depth-related gradients in the resource landscape, capturing zooplankton at deeper depths to offset the reduction in autotrophic energy sources (Muscatine et al. 1989a; Fabricius and Klumpp 1995). Indeed, increasing evidence suggests that heterotrophy, in addition to autotrophy, is a critical strategy helping to explain the persistence of corals under harsh environmental conditions (Anthony 2006; Borell et al. 2008) and their resilience following acute disturbance (Grottoli et al. 2006; Connolly et al. 2012; Levas et al. 2016).

On coral reefs, depth is commonly presented as a reliable proxy for changes in the resource landscape that should predict the trophic response of mixotrophic corals and their relative reliance on autotrophy and heterotrophy (Muscatine and Porter 1977; Muscatine et al. 1989a; Muscatine and Kaplan 1994). However, the generality of a shift from autotrophy to heterotrophy in mixotrophic corals with increasing depth (a pattern we term trophic zonation), varies across contexts. For example, in the Bahamas the reef-building coral Montastraea cavernosa shows clear trophic zonation, with a decrease in gross primary productivity and a marked transition to heterotrophy at deeper (45–61 m) depths (Lesser et al. 2010). In contrast, three species of Madracis spp. in the Caribbean and two coral species in the Red Sea (Favia favus and Stylophora pistillata) displayed comparable degrees of heterotrophy from surface waters to 47 and 60 m, respectively (Alamaru et al. 2009). Such patterns highlight the need to understand why corals would or would not exhibit trophic zonation across depth gradients.

Depth may not always act as a simple predictor of heterotrophic resource availability. Fine-scale oceanographic gradients can result in spatial disparities in energetic subsidies on coral reefs beyond first-order predictions based on depth alone. While light availability is related quite consistently to depth, spatiotemporal variations in upwelling (Gove et al. 2006), internal wave frequency (Sevadjian et al. 2012; Storlazzi et al. 2013), and surface downwelling (Monismith et al. 2006) all likely contribute to establishing depth-related variation in the availability of passive heterotrophic subsidies. Laboratory experiments have revealed many complexities associated with energy uptake and trophic strategies in mixotrophic corals, such as the bidirectional flow of both autotrophic and heterotrophic carbon between host and symbiont (Hughes et al. 2010) and the numerous species-specific differences in metabolic demands and resource acquisition (Houlbreque and Ferrier-Pagès 2009; Tremblay et al. 2015). However, in situ studies pairing oceanographic drivers of heterotrophic resource delivery with biological exploitation by mixotrophs across depth gradients on tropical coral reefs are more limited. By integrating high-resolution oceanographic sampling and isotopic analyses (δ13C and δ15N) across several producer and consumer levels, we assess evidence for the presence/absence of trophic zonation and its oceanographic correlates in a hard and soft coral in a shallow (≤ 30 m) coral reef ecosystem.

Materials and methods

Study site

Data were collected at Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge, equatorial Pacific (Fig. 1a). Palmyra is an uninhabited atoll with reefs dominated by calcifying organisms (Williams et al. 2013) and is composed of vegetated islets that partially encircle a lagoon, causing heterogeneous interchange of waters between reef habitats (Rogers et al. 2017). Our surveys focused on the forereef habitat across three depth strata (10, 20, and 30 m) at four sites (Fig. 1a). As with other equatorial Pacific islands, Palmyra experiences a relatively low seasonal sea-surface temperature (SST) range of ~ 1.5 °C, with an upper and lower climatological limit of 28.76 and 27.30 °C, respectively (Gove et al. 2013). Mean SST at Palmyra equals 27.97 °C (Gove et al. 2013) and this is relatively stable until ~ 80–90 m depth, at which point temperature rapidly drops off to between 11 and 12 °C by ~ 200 m depth (Fig. 1b). Surface waters at Palmyra contain higher chlorophyll-a concentrations than many other non-equatorial islands in the Pacific (Gove et al. 2013), however, surface NO3 concentrations are still relatively low (< 2 µmol L−1) and do not increase appreciably until the concurrent shift in temperature at ~ 80–90 m depth (Fig. 1b). By ~ 200 m depth, NO3 concentrations approximate 30 µmol L−1. Therefore, even small drops in seawater temperature of < 1 °C, driven by deep-water internal waves moving up into the shallows, are indicative of water masses originating from depths > 100 m that have the potential to significantly raise NO3 concentrations on the shallow reef (Fig. 1b).

a Location of Palmyra Atoll in the central Pacific Ocean and the four study sites on the northern and southern forereef habitat. b Vertical profiles of observed ocean temperature (solid) and nitrate concentrations (dotted) computed as a horizontal average from a 1° × 1° box centred on the island. Data obtained from the world ocean atlas (https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/woa13/)

Quantifying intra-island biophysical gradients

Photosynthetic active radiation (PAR)

Palmyra has a small footprint (2.23 km2 land mass) and minimal annual variation in insolation (Gove et al. 2013). We, therefore, expected gradients in light availability to be vertically constrained yet consistent across sites. To confirm this, irradiance was measured in 5 min intervals for 24 h at each station (with ‘station’ defined as one of 12 unique combinations of site and depth) using Onset HOBO® Pendant UA-002-64 loggers (n = 3 loggers per station). Light, measured in lux, was converted to the availability of photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) using the following conversion: 1 μmol quanta (400–700 nm) m−2 s−1 = 51.2 lx (Valiela 1984). These conversions were validated by additional in situ PAR measurements made for several hours at each depth using a 4π quantum light sensor (LICOR). Before deployment, HOBO loggers were calibrated in a common vessel to determine instrument offsets; in situ PAR data were then adjusted to the difference from the grand mean prior to analysis. PAR data were summarised as the percentage of daily maximum; maximum light intensity was presumed to occur at midday and was calculated as the mean PAR from 11 am to 1 pm daily.

Dissolved inorganic nutrients

Inorganic nutrient availability can alter the coral-algal symbiosis by increasing pigment content and density of endosymbionts (Marubini and Davies 1996; Chauvin et al. 2011). Increased symbiont pigment content or cell density can increase carbon cycling and primary production within the coral host and may alter the isotopic composition of coral tissues (Swart et al. 2005). Thus, we sampled inorganic nutrient concentrations at each of our study locations over several days and tidal cycles to determine if the nutrient availability was homogenous. A consistent nutrient environment reduces the likelihood that inter-site variation in coral photobiology varied at the time of our study and is, therefore, unlikely to strongly influence observed differences in the chemical composition of coral tissues. We collected triplicate water samples at each sampling station (3–5 samples collected on different days and times at each station to capture variations in tidal cycles) using pre-rinsed 60 mL syringes, that were then filtered through 1.2 µm GF/C filters (Whatman) and immediately frozen at − 20 °C until analysis. Samples were analysed for dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN, nitrate + nitrite + ammonia) and phosphate using a QuickChem 800 flow injection analyser (Lachat Instruments) at the Marine Science Institute Analytical Laboratory (University of California, Santa Barbara).

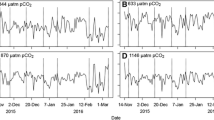

Internal waves and surface downwelling

Throughout this study, internal waves and surface downwelling events were hypothesised as key delivery mechanisms for passive particles (heterotrophic subsidies) to shallow water mixotrophs. Internal waves are common at Palmyra, delivering deep sub-thermocline water to the shallows (Gove et al. 2015), while Palmyra’s shallow reef terrace and lagoon habitats harbour particulate-rich waters (McCauley et al. 2012) that are transported out onto the forereef habitat in some locations (Rogers et al. 2017). To quantify our two suspected drivers of heterotrophic subsidies, we measured drops in temperature (cold-pulses) and the associated water flow direction over 1.77 years (654 days, October 3, 2012 to July 17, 2014). Temperature data were collected using a vertical array of Sea Bird Electronics 56 temperature loggers (10 s sample rate, 0.002 °C accuracy) moored to the reef floor at each station. To qualify as a cold-pulse within each time series (1) the rate of change of temperature (T) with respect to time (t) had to maintain a gradient of ≤ − 0.3 °C/240 min, and (2) the total change in temperature (ΔT) had to be ≤ − 0.3 °C (Sevadjian et al. 2012). The duration of each cold-pulse was calculated as the time from the initial decrease in temperature to the minimum temperature; a cold-pulse concluded when the decrease in temperature returned to 0.5 × ΔT. To minimise temperature variation from large-scale tidal flow on the analysis of cold-pulses, the time window used for analysis was less than the principal (M2) tidal return period (≤ 12.4 h). Velocity data were collected at the 20–30 m depth strata across sites using RDI ADCPs and Nortek Aquadopp Profilers (5 min sampling rate over the same 1.77 years) (see Table 1 for depth, duration, and timing of all instrument deployments). Cold-pulses originating from below were associated with an initial onshore movement of water and subsequent oscillations up and down the reef slope, suggesting the temperature drop was caused by a deep-water internal wave (Leichter et al. 1996), hereafter referred to as a “deep-pulse” (Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, cold-pulses originating from above were associated with an offshore movement of water near the benthos, suggesting a surface-derived plunging flow (Monismith et al. 2006), also known as a gravity current (Simpson 1982) and hereafter referred to as a “surface-pulse” (Fig. 2c, d). These surface-pulse water masses likely form on the shallow reef and lagoon habitats at night due to differential cooling which then, due to differences in density or mean flows, move out over the reef crest and onto the forereef slope (see Supplemental Videos 1–2 for examples of deep-pulses and Supplemental Video 3 for an example of a surface-pulse at Palmyra).

Example deep-pulse (a) and surface-pulse (c) temperature drop on Palmyra’s northeast and northwest forereef habitat, respectively. Deep-pulses occur as a result of shoaling internal waves originating from below moving cooler deep water up the reef slope in an onshore direction (as indicated by the positive velocity values at the onset of the cooling event). Cooling first occurs at 30 m, then 20 m, and finally 10 m (a), with the subsequent oscillations in velocity occurring as a result of the wave retreating and advancing on the reef slope (b). In contrast, surface-pulses originate from above and move in an offshore, downslope direction (as indicated by the negative velocity values), first cooling 10 m, then 20 m and finally 30 m (d). These surface-derived cold-pulses likely form on the shallow reef and lagoon habitats at night due to differential cooling, which then due to differences in density or mean flows, move offshore over the reef crest and onto the forereef slope

Hydrodynamic connectivity between reef habitats

To identify the source locations of water masses causing surface-pulses and to begin synthesising an estimate of connectivity to the particulate-rich shallow terrace and lagoonal waters, we derived estimates of hydrodynamic connectivity between Palmyra’s shallow reef terrace (< 10 m depth) and interior lagoon habitats with our four forereef study sites. We used a previously validated wave and hydrodynamic model (ROMS/SWAN), using passive Lagrangian tracer particles and averaged over many model runs with different flow conditions (Rogers et al. 2017), the results of which are incorporated here. This analysis assumed hydrodynamic regions of similar size, therefore, the results pertain to an average of the forereef region near each of the four forereef sites, and thus localised effects are not captured by this analysis. Additionally, the analysis assumes connection for any particle passing over a region which may or may not be in contact with the bottom.

Biological sampling framework and expectations

To ensure a robust interpretation of our results, we designed an integrated sampling framework that involved stable isotope analyses (δ13C and δ15N) of four key functional groups (calcified macroalga, planktivorous fish, hard coral, soft coral) representing different trophic strategies (obligate autotroph, obligate heterotroph, and two mixotrophs, respectively).

To track the relative delivery of different nitrogen sources across stations (i.e. from the lagoon versus offshore), we used the common reef alga Halimeda opuntia. Marine macroalgae provide an integrated history of nutrient delivery to ecosystems due to their rapid uptake of available nutrients and lack of isotopic discrimination (Fong et al. 1994; Cohen and Fong 2005). Nitrogen sources at Palmyra are distinct and easier to interpret than locations with multiple point sources of terrestrial run-off. Internal waves at Palmyra deliver sub-thermocline nitrogen that is predicted to have more enriched δ15N values (~ 12‰ at 5.7°N) due to latitudinal patterns of biological uptake and fractionation of the NO3- pool with increasing distance from the equatorial upwelling region (see Fig. 4, bottom panel in Altabet 2001). In contrast, surface downwelling delivers nutrient-rich waters from Palmyra’s lagoon that have previously been reported as having more deplete δ15N values (~ 8.2‰) (Young et al. 2010) and which we measured as ~ 8.1‰ in this study (see Supplemental Methods). We, therefore, expected enrichment in 15N in H. opuntia with increasing depth due to greater exposure to deep-water nitrogen (~ 12‰ at 5.7°N, Altabet 2001) and more deplete δ15N signatures where lagoon-derived nitrogen input was abundant (~ 8.1–8.2‰).

To provide an isotopic baseline for an obligate heterotroph we sampled the common zooplanktivorous damselfish Chromis margaritifer which is generally site-attached to its recruited depth (Hobson 1991). We expected the isotopic signatures of C. margaritifer to approximate that of the forereef zooplankton community and vary minimally across depths unless in the event of dramatic vertical shifts in zooplankton community structure (Hamner et al. 1988). We also collected near-reef zooplankton (> 200 µm) from the forereef using an autonomous sampling unit (sensu Alldredge and King 2009) (Supplemental Figure S1). In short, water was drawn in through a funnel positioned ~ 0.75 m off of the reef floor using a bilge pump (Rule 1500) and filtered onto 200 µm plankton mesh held within a contained unit. Upon collection, the zooplankton were concentrated onto a fresh 200 µm mesh, placed in pre-combusted aluminium foil, and subsequently frozen at − 20 °C within 1 h. The total amount of water filtered was recorded by a flow meter (Dwyer WM Multi-Jet) with a digital timer (Flexcharge digital DC timer) to ensure comparable temporal sampling across stations. At each station, zooplankton were collected across entire diel cycles (30 min sampling intervals every 4 h over two 24-h periods per station). Due to this relatively low replication across stations, samples were pooled to obtain a mean isotopic signature for the zooplankton community.

Finally, to test for the evidence of trophic zonation in mixotrophs across depths, we sampled the hard coral Pocillopora meandrina and the soft coral Sinularia sp. (we do not provide a species name for the soft coral, although based on gross morphology we identified it as Sinularia cf. sublimis). We were not interested in directly comparing the two species, but instead quantifying the strength of trophic zonation in two mixotrophs with different morphologies and functional roles. To test for changes in the relative contribution of carbon acquired through heterotrophic feeding, we use the metric Δδ13C, which is the difference in the δ13C value between the host (animal) and endosymbiont (algal) fractions (Muscatine et al. 1989a). This metric provided insight into relative incorporation of heterotrophic carbon by the coral host and has been used to track relative trophic contributions in a number of coral species (Muscatine et al. 1989a; Rodrigues and Grottoli 2006; Lesser et al. 2010; Schoepf et al. 2015; Plass-Johnson et al. 2016). Our expectation was that the metabolic demands of the coral animal must be subsidised through heterotrophy with increasing depth (Muscatine et al. 1989a; Alamaru et al. 2009; Tremblay et al. 2015). Due to lower photosynthetic and metabolic rates (Muscatine et al. 1989a; Muscatine and Kaplan 1994; Heikoop et al. 1998) and increased recycling of resources (Alamaru et al. 2009; Reynaud et al. 2009), the δ13C and δ15N signatures of both fractions should become more depleted with depth. Symbiodinium spp. rely heavily on respired CO2 from the coral host for photosynthesis, and thus tend to be more enriched in 13C relative to the animal fraction and local zooplankton communities (Muscatine et al. 1989a). Consequently, as the reliance on heterotrophic feeding by the coral animal increases, the δ13C signature of the animal fraction should shift towards that of the zooplankton community and further from the endosymbiont value despite the natural depletion in both fractions with depth (Muscatine et al. 1989a). Thus, we expected Δδ13C to become more negative with an increased reliance on heterotrophy.

Sample collection and processing for stable isotope analyses

All biological specimens were collected over a 6-day period during September 2012 using closed-circuit rebreathers to sample all depth strata in a single dive at any given site (see Table 1 for sampling effort across stations). Fragments (~ 3 cm2) of the hard coral P. meandrina and the soft coral Sinularia sp. were collected from the centre-top of each individual. The planktivorous fish C. margaritifer were collected using hand nets, targeting a range of sizes (20–100 mm). Samples of the calcified macroalga, H. opuntia, were collected, targeting specimens that were free as much as possible from epiphytes or crustose coralline algae. Replicate individuals within each functional group were haphazardly chosen along a 50 m transect at each station, but always a minimum of 5 m apart. All specimens were prepared largely according to established protocols for stable isotopic analyses of coral reef organisms (Muscatine and Kaplan 1994, Grottoli et al. 2004) (see Supplemental Methods for full description of sample processing for isotope analyses and Table 1 for sampling effort across functional groups). All isolated biological fractions were analyzed for δ13C and δ15N with a Costech 4010 Elemental Combustion Analyzer interfaced with a Thermo Finnigan Delta Plus XP stable isotope mass spectrometer (San Jose, CA) at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Isotopic values are expressed as δ13C, where δ = 1000 × [(Rsample/Rstandard) − 1] and Rsample or Rstandard are the ratio of the heavy to light isotope in parts per thousand, or per mil (‰). The calibration standards used were Vienna-Pee Dee Belemnite (V-PDB) and atmospheric N2. Within-run standard deviations of three Acetanilide standards (Baker A068-03) were < 0.1‰.

Inferring species-specific change in isotope signatures

We used a two factor (both fixed) analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the effects of site (four levels) and depth (three levels) on the stable isotope ratios from the tissue of each organism. Normality and homoscedasticity were verified using the Anderson–Darling test and Levene’s test, respectively. Subsequent pairwise analyses were completed using a Tukey’s test (planned contrasts between depths within sites). Our prediction was that if depth were a good proxy for vertical gradients in the resource landscape we should expect to see consistent effects of depth across sites and no interaction between the two factors. When testing for variations in the relative degree of heterotrophy (Δδ13C), we were only interested in depth variations within sites and thus used a single fixed factor (depth, three levels) ANOVA. Our prior hypothesis-driven approach was favoured over a post hoc isotopic mixing model for two reasons. First, it gave us greater inferential power to test our a priori natural experimental set-up. Second, the complex cycling of nutrients and heterotrophic carbon between the endosymbionts and coral host (Hoogenboom et al. 2015) confounds the ability to identify a pure ‘source’ component for the endosymbionts (hence our use of the Δδ13C metric).

Correlating biophysical gradients and coral trophic zonation

To characterise oceanographic conditions across stations, we derived the following metrics: (1) frequency of deep- and surface-pulses (mean number per week), (2) percentage propagation of deep- and surface-pulses between depths (i.e. the % of deep-pulses arriving at 30 m that then transitioned up to 20 and 10 m, and vice versa for surface-pulses), (3) total summed duration of all deep- and surface-pulses (in minutes), (4) mean and standard deviation (SD) duration of any single deep- and surface-pulse event (in minutes), (5) mean and SD temperature change associated with deep- and surface-pulse events (∆°C), and (6) degree cooling weeks, whereby a running sum of temperature change is multiplied by the total time and then summed over all surface- and deep-pulses (°C-weeks) (Table 2). To relate changes in the degree of heterotrophy in the two mixotrophs to these gradients in oceanography (while acknowledging the inherent autocorrelation between sites and among depths within any one site), we used metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) constructed from a distance matrix, which in our case was pairwise Euclidean distances of ∆δ13C for both mixotrophs simultaneously. Prior to constructing the MDS, we assessed for colinearity between our oceanographic correlates using a principal component analysis (PCA) and pairwise Pearson’s correlations of their normalised values. We focused here on those metrics best capturing ‘exposure’ to deep- and surface-pulses, namely total summed duration, mean (and SD) duration of any single event and degree cooling weeks. We defined a threshold r value of 0.7 and excluded one of any pair exceeding this. Total summed duration correlated strongly (> 0.9) with the degree cooling weeks for both deep- and surface-pulses; total summed duration was chosen as a more intuitive metric. Mean duration of events also correlated strongly (> 0.75) with its SD for both deep- and surface-pulses; the mean was selected as a more intuitive metric. Finally, to visualise the correlation between coral trophic zonation and potential nitrogen sources (as an indicator of oceanographic connectivity with the lagoon versus offshore waters), we included the macroalgal δ15N signatures. These three metrics (total summed duration, mean duration and macroalgal δ15N) were normalised and then overlaid as a biplot on the MDS plot to visualise their correlation with the first two ordination axes. All statistical analyses were completed using R version 3.3.3 (http://www.r-project.org) and the vegan package (Oksanen et al. 2018).

Results

Intra-island biophysical gradients

Photosynthetic active radiation (PAR)

The delivery of PAR to the reef benthos decreased rapidly with depth at all sites. Relative to 10 m depth, where mean PAR (± 1 SE) was 446 ± 11 µmol photon m−2 s−1, the daily maximum level decreased 13–22% by 20 m across sites (mean = 372 ± 9 µmol photon m−2 s−1) and 43–61% by 30 m across sites (mean = 196 ± 5 µmol photon m−2 s−1).

Dissolved inorganic nutrients

Dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) did not vary with site (F3,29 = 2.48, p = 0.08) or depth (F3,29 = 0.86, p = 0.43) and there was no significant interaction between the two factors. Across all stations, mean (± 1 SE) DIN concentration equalled 1.13 (± 0.09) µmol. Similarly, phosphate concentrations did not differ with site (F3,29 = 1.65, p = 0.19) or depth (F3,29 = 1.60, p = 0.22), and again there was no significant interaction between the two factors. Across all stations, mean (± 1 SE) phosphate concentration equalled 0.15 (± 0.02) µmol.

Internal waves and downwelling

The magnitude of temperature change associated with deep- and surface-pulse events was relatively consistent between stations (0.34–0.52 °C, Table 2) and while small, were significant when considered in the context of Palmyra’s low seasonal SST range of ~ 1.5 °C (Gove et al. 2013). However, the frequency and duration of deep- and surface-pulse events varied spatially (Table 2). Exposure to deep-pulses increased with increasing depth at all sites, with the highest frequency occurring at 30 m in the northeast and southeast (5.6 and 3.3 week−1, respectively) (Table 2). Across all sites, deep-pulses remained depth restricted, with only 4.3–8.2% of all events arriving at 30 m propagating up the reef slope to 10 m. In contrast, surface-pulses exhibited greater vertical propagation, with 29.6–53.6% of all events arriving to 10 m propagating down the reef slope to 30 m. Exposure to surface-pulses peaked in the northeast regardless of depth (1.0–2.3 week−1), however, the mean duration of any single event was longest in the northwest, lasting on average 235 min, which was 1.4–3.3 times the mean duration of surface-pulses at 10 m at all other sites (Table 2). Similarly, deep-pulses reaching 10 m lasted on average 206 min in the northwest, almost twice the duration of deep-pulses reaching 10 m at all other sites (Table 2).

Hydrodynamic connectivity between reef habitats

There were differences in the level of hydrodynamic connectivity to Palmyra’s shallow (< 10 m depth) reef terrace and the interior lagoon habitats experienced at our four forereef habitat study sites (Fig. 3). Represented as particle track counts over many ROMS model simulations normalised by the maximum total track counts (sensu Rogers et al. 2017), the southwest forereef was the most highly connected (1.00), followed by the northwest (0.53), then southeast (0.29), and finally the northeast (0.11). Relative to the least connected northeast forereef site, these values equate to the southeast being 2.6 times more connected, the northwest 4.6 times more connected, and the southwest 8.7 times more connected (Fig. 3).

Major hydrodynamic connectivity pathways between Palmyra’s shallow reef terrace (< 10 m depth) and interior lagoon habitats and our four forereef study sites. Connectivity was evaluated using a previously published wave and hydrodynamic model (ROMS/SWAN), using passive Lagrangian tracer particles and averaged over many model runs with different flow conditions (Rogers et al. 2017). Width of blue arrows indicates strength of connectivity; showing only top 30% of pathways for clarity. For any two connected locations, the direction of water flow is from the shallow reef terrace and interior lagoon habitats to one or more of our four forereef habitat study sites. Colouring indicates relative importance of each region as an overall source to the atoll. Grey shading is land, grey lines are 10 and 60 m depth contours

Nitrogen sources

The δ15N signatures of Halimeda opuntia tissue revealed a significant (F3,6 = 2.69, p = 0.025) interaction between depth and site. Depth had a significant effect in the northwest and southeast with Halimeda δ15N signatures becoming more enriched with increasing depth (Tukey HSD 10, 20 m < 30 m, and 10 m < 30 m, respectively), but no effect in the northeast and southwest where Halimeda showed consistently enriched δ15N signatures at all depths (Fig. 4). By 30 m, δ15N signatures of H. opuntia approximated that of deep-water sources of nitrogen for the region (11–13‰) at all sites (Fig. 4). In contrast, results were more variable at 10 m and sites showed a gradient from lighter δ15N values in the northwest that approximated Palmyra’s surface lagoonal-water (~ 8.3‰) to heavier deep-water sources of nitrogen in the northeast (~ 12.1‰) (Fig. 4).

Mean δ13C and δ15N isotope signatures (± 1SE) for the hard coral Pocillopora meandrina (animal fraction), the soft coral Sinularia sp. (animal fraction), the calcified macroalga Halimeda opuntia, and the planktivorous fish Chromis margaritifer across three depth strata (10, 20, 30 m) at four sites on Palmyra’s forereef (see Table 1 for sample sizes). Dashed lines represent the mean signature for near-reef zooplankton collected over averaged diel cycles on the forereef. Black arrowhead on y-axis indicates the δ15N signature of surface lagoonal-wash at Palmyra

Species-specific isotope signatures

There was a significant interaction between depth and site on the δ13C signatures of the hard and soft coral animal tissue (F3,6 = 2.40, p = 0.033 and F3,6 = 2.25, p = 0.049, respectively) and planktivorous fish (F3,6 = 3.81, p = 0.002). At three of the sites (southwest, southeast, and northeast) depth consistently acted as a reliable predictor of δ13C signatures of all three groups, with signatures becoming more negative with increasing depth (Tukey HSD showed differences between 10 and 30 m in all cases) (Fig. 4). At these three sites, the relative decreases in δ13C of the planktivorous fish with increasing depth were small (generally < 1‰) with the mean δ13C signature across all depths close to the zooplankton basal source (Fig. 4). In contrast, animal tissue of both hard and soft corals spanned larger ranges in δ13C across depths at the same three sites (3–5‰), with values moving closer to the δ13C signatures of zooplankton at deeper depths.

There was a significant effect of depth on the relative degree of heterotrophy (∆δ13C) by hard corals in the southwest (F2,28 = 67.26, p = < 0.001), southeast (F2,29 = 11.50, p = < 0.001), and northeast (F2,29 = 115.18, p = < 0.001) and by soft corals in the southeast (F2,18 = 14.36, p = < 0.001) and northeast (F2,27 = 27.76, p = < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons between depths indicated strong trophic zonation with an increased reliance on heterotrophic sources of carbon with increasing depth (Tukey HSD showed differences between 10 and 30 m in all cases) (Fig. 5a, b). In contrast at the fourth site (northwest), there was no effect of depth on the δ13C signatures of the hard coral, soft coral, or planktivorous fish (Fig. 4). In addition, at the northwest site, there was no significant effect of depth on the isotopic discrepancy between symbiont and host tissue in either hard or soft corals (Fig. 5a, b).

Mean (± 1 SE) relative degree of heterotrophy (RDH, ∆δ13C = δ13CANIMAL − δ13CENDOSYMBIONT) in the hard coral Pocillopora meandrina (a) and the soft coral Sinularia sp. (b) across three depth strata (10, 20, 30 m) at four forereef sites on Palmyra Atoll and the correlation of this with several biophysical metrics (c). The correlation of the biophysical metrics with the first two MDS axes is overlaid as a biplot. The vector lines represent the Pearson’s correlations, with the direction indicating the relationship of each biophysical metric to the variation in RDH among stations. The length of each vector is proportional to the strength of the correlation. DP deep-pulse, SP surface-pulse, total time total summed duration of events (in minutes), mean duration mean duration of any single event (in minutes), N15 δ15N signature of the macroalga Halimeda opuntia

In contrast to the animal tissue, the δ13C of the endosymbiont fraction of the hard coral showed consistent δ13C signatures across depths within each site. The endosymbiont fraction of the soft coral, however, showed significant effects of depth (F2,4 = 4.62, p = 0.014) and site (F2,4 = 6.90, p = 0.002) and no interaction between the two factors. Soft coral endosymbiont δ13C became more negative with increasing depth and overall were lighter in the northwest than in either the northeast or southeast; however, this site effect was small (generally < 1‰). In comparison, depth had no significant effect on H. opuntia δ13C and the only site-level difference (F2,4 = 4.62, p = 0.014) occurred between the northwest and northeast sites (Fig. 4).

There was a significant interaction between depth and site on the δ15N signatures of the animal and endosymbiont fractions of the hard coral (F3,6 = 4.22, p < 0.001 and F3,6 = 4.20, p < 0.001, respectively). Depth effects were only realised for the animal fraction in the northeast, with signatures more enriched at 10 m than at 30 m (Fig. 4). A similar depth effect occurred for the endosymbiont fraction in the northeast and southeast; here δ15N signatures became lighter with increasing depth. Neither depth nor site had any effect on the δ15N signatures of the soft coral animal fraction, however, there was a site effect on the endosymbiont fraction (F2,4 = 6.70, p = 0.002), with more enriched values in the northeast as compared to the northwest, however, this difference was small (< 0.7‰). Finally, there was a significant interaction between site and depth on the δ15N signatures of the planktivorous fish (F3,6 = 9.85, p = < 0.001); signatures consistently decreased with depth at the two southern sites (Fig. 4).

Biophysical correlates of coral trophic zonation

The first axis of the MDS was strongly correlated with an increasing gradient, moving left to right, in the relative degree of heterotrophy (∆δ13C) in the two mixotrophs (Fig. 5c). Along this axis, higher values of the relative degree of heterotrophy primarily correlated with higher total exposure to deep-pulses and exposure to surface-pulses of a higher mean duration (Fig. 4c). The consistent increase in the exposure to deep-pulses with increasing depth regardless of site (Table 2) suggested the upslope transport of cool water likely drove the general increase in the degree of heterotrophy with increasing depth (along MDS axis 1), while the lack of trophic zonation in the northwest correlated most strongly with increased mean duration of surface-pulses in the shallows in this region (Fig. 5c, Table 2).

Discussion

Depth predicts species-specific trophic responses

By integrating high-resolution oceanographic sampling with isotopic analyses, we found fine-scale gradients in physical processes across depths and patterns of hydrodynamic connectivity between habitats to be reflected across multiple trophic levels on a shallow (≤ 30 m) coral reef ecosystem. We saw evidence of trophic zonation in two mixotrophs, with a reliance on autotrophy in the shallows and an increasing reliance on heterotrophy with increasing depth. However, within the same study system we saw site-specific absence of trophic zonation and propose that intra-island gradients in oceanographic processes can shift simple depth-dependent patterns of resource availability. The absence of trophic zonation in mixotrophs at some study locations may, in part, reflect the fact that corals will exploit heterotrophic resources regardless of depth if they are available due to the numerous physiological and ecological benefits heterotrophy confers (Grottoli et al. 2006, Houlbreque and Ferrier-Pagès 2009).

Depth was a reliable predictor of the trophic response of mixotrophic organisms in locations where light availability and deep-pulses indicative of internal waves were inversely related. At such locations, internal waves brought cool waters up from depth, likely delivering heterotrophic energetic subsidies to consumers for exploitation (Wolanski and Delesalle 1995; Leichter et al. 1996, 1998), as evidenced by isotopic patterns of the hard coral Pocillopora meandrina and the soft coral Sinularia sp. (Figs. 4, 5). Increased exposure to internal waves correlated with increased degrees of heterotrophy in the two mixotrophs, particularly at deeper depths where internal waves most frequently reached (Table 2, Fig. 5c). As such, with increasing depth, the δ13C signature of the animal tissue from both hard and soft corals migrated closer to that of the near-reef zooplankton, likely signifying increased reliance on zooplankton as a food source. Moreover, the difference between the δ13C of the animal and of the algal fractions (∆δ13C) increased with depth, indicating incorporation of heterotrophic carbon by the animal host at deeper depths (Muscatine et al. 1989b; Palardy et al. 2005). Importantly, minimal changes in the δ13C of the endosymbiont fractions occurred across depth in both coral species, suggesting no substantial change in photosynthetic fractionation with increasing depth. Thus, the contrasting depletion in 13C in the coral host tissue along the same depth gradient is likely indicative of a greater incorporation of heterotrophic carbon rather than changes in the δ13C of autotrophic carbon translocation from the endosymbionts.

In contrast to δ13C, the δ15N of the animal fraction of both mixotrophs remained stable across depth with the exception of the hard coral at the northeast site, where individuals became depleted in 15N with increasing depth. Experimental feeding trials have shown δ15N depletion to occur in corals due to an increased reliance on heterotrophy and nitrogen-recycling between the host and symbiont (Muscatine and D’elia 1978; Reynaud et al. 2009). The zonation in δ15N in the hard coral in the northeast supports this nitrogen-recycling theory. Importantly, the depth-restricted nature of internal waves in the northeast of Palmyra is likely creating strong vertical gradients in heterotrophic resource availability, and thus emphasising the depletion of δ15N across depth at this site. Additionally, the depletion in δ15N with depth observed in the algal fraction of the hard coral is consistent with previous studies showing increased fractionation of nitrogen with a decrease in light availability (Muscatine and Kaplan 1994; Heikoop et al. 1998). Contrary to the previously observed patterns of endosymbiont δ15N in hard corals, the endosymbionts of the soft coral Sinularia sp. showed no appreciable change across depths. The observed differences in endosymbiont δ15N between our hard and soft coral taxa suggest that the nitrogen allocation and acquisition of soft coral endosymbionts may be regulated differently than in hard corals.

In contrast to the mixotrophs, the planktivorous fish showed less variation in its δ13C signature with depth, with signatures of individuals from all depths approximating that of their zooplankton basal source. Although statistical effects of depth were found in the fish, differences between individuals from the depth extremes (10 versus 30 m) were within ~ 1‰ δ13C of each other and unlikely to be ecologically relevant. There was, however, evidence of enriched δ15N in the fish in the shallows as compared to deeper depths. This could reflect a shift in prey consumption, with the shallow fish communities selectively targeting (Hanson et al. 2016), or being limited to, a higher proportion of predatory plankton that are themselves more enriched in δ15N (Hobson 1991).

Biophysical conditions resulting in an absence of coral trophic zonation

At our northwest study site, trophic zonation was not evident in either the hard or soft corals. δ13C values of both groups were similar at all depths, approximating those of the planktivorous fish, which were within 1.5‰ δ13C of the near-reef zooplankton basal source. Moreover, the relative degree of heterotrophy (∆δ13C) by hard and soft corals was not only similar across depths, but was among the highest within the shallows (Fig. 5a, b). Patterns of δ13C in mixotrophs can be influenced by a number of physiological and environmental factors. For example, changes in the availability of light or inorganic nutrients can alter endosymbiont density and coral photosynthetic rates (Falkowski et al. 1984; Wyman et al. 1987; Marubini and Davies 1996) which in turn could alter patterns of carbon fractionation and, therefore, tissue δ13C of both the host and endosymbiont (Swart 1983; Swart et al. 2005). The influence of symbiont demographies on coral ∆δ13C, however, appears varied. Two studies report opposing relationships between ∆δ13C and endosymbiont density (Swart et al. 2005; Hoogenboom et al. 2015), while others report no relationship at all (Nahon et al. 2013). Importantly, we found no differences in inorganic nutrient concentrations or mean irradiance between our sites at Palmyra and we found the consistency of δ13C of Halimeda opuntia across depths at all four sites (Fig. 4), together suggesting a common carbon source and insufficient changes in photosynthetic rates to alter fraction patterns of 13C (Kübler and Raven 1995). We, therefore, hypothesize that the absence of trophic zonation in both mixotrophs in the northwest is due to the lack of stratification in heterotrophic resources across depths, rather than site-level differences in photosynthetic rates or PAR.

But how does this lack of stratification in heterotrophic resources occur? Recall that macroalgae provide an integrated assessment of nutrient delivery to the system, with the δ15N signatures of individuals reflective of the dominant sources of nitrogen in the surrounding waters (Fong et al. 1994; Cohen and Fong 2005). In the northeast forereef of Palmyra, where coral trophic zonation was most pronounced, the hydrodynamic connectivity to shallow interior waters was the lowest of all four study sites (Fig. 3) and the δ15N signature of the macroalga Halimeda opuntia approximated that previously reported for sinking POM in the equatorial Pacific (~ 12‰) (Altabet 2001) at all depths (Fig. 4). This suggests that macroalgae here are limited to isotopically heavier deep-water sources of nitrogen (Leichter et al. 2003; Smith et al. 2004), despite the site experiencing the highest total exposure to surface-pulse events (Table 2). In contrast, in the northwest forereef where coral trophic zonation was absent, the site had 4.6 times the hydrodynamic connectivity to Palmyra’s shallow interior waters than that of the northeast site (Fig. 3). This increased connectivity to shallow, particulate-rich interior waters was also reflected in the macroalgal individuals, with those individuals in the shallows having approximately the same δ15N signature as that reported for surface lagoonal-water at Palmyra (~ 8.1–8.2‰, Young et al. 2010 and this study). We hypothesise that the transport of particulate-rich lagoonal waters to the forereef in this location by downwelling (surface-pulses) causes a breakdown in coral trophic zonation. By combining lagoon-derived, resource-rich downwelled waters with the more common resource-rich upwelled waters delivered by internal waves, the gradient in heterotrophic resources loses its direct linkage with depth. Instead, the isotopic patterns in both mixotrophs in the northwest speak to heterotrophic food resources being abundant at all depths and add credibility to our hypothesis that internal waves and surface-downwelling represent key delivery mechanisms of heterotrophic subsidies on oceanic coral reef atolls. Importantly, the mean duration of any single surface-pulse event appeared more important in driving a lack of trophic zonation than the total summed duration of all events (Fig. 5c). The temperature changes associated with surface-pulses in the northwest where trophic zonation was absent lasted on average twice that of all other sites (Table 2). Increased exposure time may facilitate biological uptake and assimilation of heterotrophic subsidies (Atkinson and Bilger 1992; Steven and Atkinson 2003), allowing corals to make best use of particulate-rich, lagoonal waters. There are several oceanographic mechanisms that can result in a lack of stratification of the water column on coral reefs, including wave-driven circulation (Lowe and Falter 2015), current-driven upwelling (Gove et al. 2006), and thermally driven downwelling (Monismith et al. 2006). A lack of heterotrophic-resource stratification may, therefore, be common yet site-specific on coral reefs, helping to explain instances of a lack of trophic zonation reported for mixotrophic corals across depth gradients.

Conclusions and future directions

Depth can be a reliable model for predicting patterns of trophic zonation in coral reef mixotrophs. When a rapid loss of light with increasing depth correlates with vertical water flow dominated by high frequency and duration of deep-water internal waves, mixotrophic corals display clear evidence of trophic zonation, increasing their reliance on heterotrophy relative to autotrophy with increasing depth. However, in some locations depth can be an unreliable predictor of a mixotrophs trophic response. Where high frequencies of deep-water internal waves coincide with frequent and long-lasting surface downwelling events that deliver particulate-rich lagoonal waters to shallow depths, trophic zonation is no longer evident and mixotrophic corals display a strong reliance on heterotrophy regardless of depth. We hypothesise that this lack of trophic zonation occurs due to the combination of oceanographic processes causing heterotrophic resources to be more homogenously distributed across depths. Such context-specificity of unique oceanographic regimes may explain why signals of trophic zonation on coral reefs are so variable and why depth alone may sometimes be a poor predictor of the trophic response of shallow-water mixotrophs. Future studies on the trophic plasticity of mixotrophic corals should consider incorporating more detailed in situ assessments of coral photosynthetic rates across natural resource gradients to improve our understanding of where the autotrophic and heterotrophic trade-offs exist for species with flexible trophic strategies.

References

Alamaru A, Loya Y, Brokovich E, Yam R, Shemesh A (2009) Carbon and nitrogen utilization in two species of Red Sea corals along a depth gradient: insights from stable isotope analysis of total organic material and lipids. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 73:5333–5342

Alldredge A, King J (2009) Near-surface enrichment of zooplankton over a shallow back reef: implications for coral reef food webs. Coral Reefs 28:895–908

Altabet MA (2001) Nitrogen isotopic evidence for micronutrient control of fractional NO3-utilization in the equatorial Pacific. Limnol Oceanogr 46:368–380

Anthony KRN (2006) Enhanced energy status of corals on coastal, high-turbidity reefs. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 319:111–116

Atkinson MJ, Bilger RW (1992) Effects of water velocity on phosphate uptake in coral reef-flat communities. Limnol Oceanogr 37:273–279

Borell EM, Yuliantri AR, Bischof K, Richter C (2008) The effect of heterotrophy on photosynthesis and tissue composition of two scleractinian corals under elevated temperature. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 364:116–123

Chauvin A, Denis V, Cuet P (2011) Is the response of coral calcification to seawater acidification related to nutrient loading? Coral Reefs 30:911

Cohen R, Fong P (2005) Experimental evidence supports the use of δ15 N content of the opportunistic green macroalga Enteromorpha intestinalis (Chlorophyta) to determine nitrogen sources to estuaries. J Phycol 41:287–293

Connolly SR, Lopez-Yglesias MA, Anthony KRN (2012) Food availability promotes rapid recovery from thermal stress in a scleractinian coral. Coral Reefs 31:951–960

Davies PS (1991) Effect of daylight variations on the energy budgets of shallow-water corals. Mar Biol 108:137–144

Fabricius KE, Klumpp DW (1995) Widespread mixotrophy in reef-inhabiting soft corals: the influence of depth, and colony expansion and contraction on photosynthesis. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 125:195–204

Falkowski PG, Dubinsky Z, Muscatine L, Porter JW (1984) Light and the bioenergetics of a symbiotic coral. Bioscience 34:705–709

Fong P, Donohoe RM, Zedler JB (1994) Nutrient concentration in tissue of the macroalga Enteromorpha as a function of nutrient history: an experimental evaluation using field microcosms. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 106:273–281

Friedlander AM, Sandin SA, DeMartini EE, Sala E (2010) Spatial patterns of the structure of reef fish assemblages at a pristine atoll in the central Pacific. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 410:219–231

Genin A, Jaffe JS, Reef R, Richter C, Franks PJ (2005) Swimming against the flow: a mechanism of zooplankton aggregation. Science 308:860–862

Genin A, Monismith SG, Reidenbach MA, Yahel G, Koseff JR (2009) Intense benthic grazing of phytoplankton in a coral reef. Limnol Oceanogr 54:938–951

Gove JM, Merrifield MA, Brainard RE (2006) Temporal variability of current-driven upwelling at Jarvis Island. J Geophys Res Oceans 111:C12011

Gove JM, Williams GJ, McManus M, Heron S, Sandin SA, Vetter OJ, Foley D (2013) Quantifying climatological ranges and anomalies for Pacific coral reef ecosystems. PLoS One 8:e61974

Gove JM, Williams GJ, McManus MA, Clark SJ, Ehses JS, Wedding LM (2015) Coral reef benthic regimes exhibit non-linear threshold responses to natural physical drivers. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 522:33–48

Grottoli AG, Rodrigues LJ, Juarez C (2004) Lipids and stable carbon isotopes in two species of Hawaiian corals, Porites compressa and Montipora verrucosa, following a bleaching event. Mar Biol 145:621–631

Grottoli AG, Rodrigues LJ, Palardy JE (2006) Heterotrophic plasticity and resilience in bleached corals. Nature 440:1186–1189

Hamner W, Jones M, Carleton J, Hauri I, Williams DM (1988) Zooplankton, planktivorous fish, and water currents on a windward reef face: Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Bull Mar Sci 42:459–479

Hanson KM, Schnarr EL, Leichter JJ (2016) Non-random feeding enhances the contribution of oceanic zooplankton to the diet of the planktivorous coral reef fish Dascyllus flavicaudus. Mar Biol 163:1–13

Heikoop JM, Dunn JJ, Risk MJ, Sandeman IM, Schwarcz HP, Waltho N (1998) Relationship between light and the δ15N of coral tissue: examples from Jamaica and Zanzibar. Limnol Oceanogr 43:909–920

Hobson ES (1991) Trophic relationships of fishes specialized to feed on zooplankters above coral reefs. The ecology of fishes on coral reefs. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 69–95

Hoogenboom M, Rottier C, Sikorski S, Ferrier-Pagès C (2015) Among-species variation in the energy budgets of reef-building corals: scaling from coral polyps to communities. J Exp Biol 218:3866–3877

Houlbreque F, Ferrier-Pagès C (2009) Heterotrophy in tropical scleractinian corals. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 84:1–17

Hughes AD, Grottoli AG, Pease TK, Matsui Y (2010) Acquisition and assimilation of carbon in non-bleached and bleached corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 420:91–101

Kübler JE, Raven JA (1995) The interaction between inorganic carbon acquisition and light supply in Palmaria palmata (Rhodophyta). J Phycol 31:369–375

Leichter JJ, Wing SR, Miller SL, Denny MW (1996) Pulsed delivery of subthermocline water to Conch Reef (Florida Keys) by internal tidal bores. Limnol Oceanogr 41:1490–1501

Leichter JJ, Shellenbarger G, Salvatore J, Wing SR (1998) Breaking internal waves on a Florida (USA) coral reef: a plankton pump at work? Mar Ecol Prog Ser 166:83–97

Leichter JJ, Stewart HL, Miller SL (2003) Episodic nutrient transport to Florida coral reefs. Limnol Oceanogr 48:1394–1407

Leichter JJ, Helmuth B, Fischer AM (2006) Variation beneath the surface: quantifying complex thermal environments on coral reefs in the Caribbean, Bahamas and Florida. J Mar Res 64:563–588

Leichter JJ, Stokes MD, Hench JL, Witting J, Washburn L (2012) The island-scale internal wave climate of Moorea, French Polynesia. J Geophys Res Oceans 117:C6

Lesser MP, Slattery M, Stat M, Ojimi M, Gates RD, Grottoli A (2010) Photoacclimatization by the coral Montastraea cavernosa in the mesophotic zone: light, food, and genetics. Ecology 91:990–1003

Levas S, Grottoli AG, Schoepf V, Aschaffenburg M, Baumann J, Bauer JE, Warner ME (2016) Can heterotrophic uptake of dissolved organic carbon and zooplankton mitigate carbon budget deficits in annually bleached corals? Coral Reefs 35:495–506

Lowe RJ, Falter JL (2015) Oceanic forcing of coral reefs. Ann Rev Mar Sci 7:43–66

Marubini F, Davies PS (1996) Nitrate increases zooxanthellae population density and reduces skeletogenesis in corals. Mar Biol 127:319–328

McCauley DJ, DeSalles PA, Young HS, Dunbar RB, Dirzo R, Mills MM, Micheli F (2012) From wing to wing: the persistence of long ecological interaction chains in less-disturbed ecosystems. Sci Rep 2:409

Monismith SG, Genin A, Reidenbach MA, Yahel G, Koseff JR (2006) Thermally driven exchanges between a coral reef and the adjoining ocean. J Phys Oceanogr 36:1332–1347

Monismith SG, Davis KA, Shellenbarger GG, Hench JL, Nidzieko NJ, Santoro AE, Reidenbach MA, Rosman JH, Holtzman R, Martens CS (2010) Flow effects on benthic grazing on phytoplankton by a Caribbean reef. Limnol Oceanogr 55:1881–1892

Muscatine L, D’elia C (1978) The uptake, retention, and release of ammonium by reef corals. Limnol Oceanogr 23:725–734

Muscatine L, Kaplan I (1994) Resource partitioning by reef corals as determined from stable isotope composition II. δ15N of zooxanthellae and animal tissue versus depth. Pac Sci 48:304–312

Muscatine L, Porter JW (1977) Reef corals: mutualistic symbioses adapted to nutrient-poor environments. Bioscience 27:454–460

Muscatine L, Porter J, Kaplan I (1989a) Resource partitioning by reef corals as determined from stable isotope composition I. δ13C of zooxanthellae and animal tissue vs depth. Mar Biol 100:185–193

Muscatine L, Falkowski PG, Dubinsky Z, Cook PA, McCloskey LR (1989b) The effect of external nutrient resources on the population dynamics of zooxanthellae in a reef coral. Proc R Soc B 236:311–324

Nahon S, Richoux NB, Kolasinski J, Desmalades M, Pages CF, Lecellier G, Planes S, Lecellier VB (2013) Spatial and temporal variations in stable carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotopic composition of symbiotic scleractinian corals. PLoS One 8:e81247

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Wagner H (2018) vegan: community ecology package. R package version 2.4-3. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018

Palardy JE, Grottoli AG, Matthews KA (2005) Effects of upwelling, depth, morphology and polyp size on feeding in three species of Panamanian corals. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 300:79–89

Palardy JE, Rodrigues LJ, Grottoli AG (2008) The importance of zooplankton to the daily metabolic carbon requirements of healthy and bleached corals at two depths. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 367:180–188

Plass-Johnson JG, McQuaid CD, Hill JM (2016) Morphologically similar, coexisting hard corals (Porites lobata and P. solida) display similar trophic isotopic ratios across reefs and depths. Mar Freshw Res 67:671–676

Reynaud S, Martinez P, Houlbrèque F, Billy I, Allemand D, Ferrier-Pagès C (2009) Effect of light and feeding on the nitrogen isotopic composition of a zooxanthellate coral: role of nitrogen recycling. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 392:103–110

Roder C, Fillinger L, Jantzen C, Schmidt GM, Khokiattiwong S, Richter C (2010) Trophic response of corals to large amplitude internal waves. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 412:113–128

Rodrigues LJ, Grottoli AG (2006) Calcification rate and the stable carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen isotopes in the skeleton, host tissue, and zooxanthellae of bleached and recovering Hawaiian corals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 70:2781–2789

Rogers JS, Monismith SG, Fringer OB, Koweek DA, Dunbar RB (2017) A coupled wave-hydrodynamic model of an atoll with high friction: mechanisms for flow, connectivity, and ecological implications. Ocean Model Online 110:66–82

Schoepf V, Grottoli AG, Levas SJ, Aschaffenburg MD, Baumann JH, Matsui Y, Warner ME (2015) Annual coral bleaching and the long-term recovery capacity of coral. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci 282:20151887

Sevadjian J, McManus M, Benoit-Bird K, Selph K (2012) Shoreward advection of phytoplankton and vertical re-distribution of zooplankton by episodic near-bottom water pulses on an insular shelf: Oahu, Hawaii. Cont Shelf Res 50:1–15

Simpson JE (1982) Gravity currents in the laboratory, atmosphere, and ocean. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 14:213–234

Smith JE, Smith CM, Vroom P, Beach KL, Miller S (2004) Nutrient and growth dynamics of Halimeda tuna on Conch Reef, Florida Keys: possible influence of internal tides on nutrient status and physiology. Limnol Oceanogr 49:1923–1936

Steven ADL, Atkinson MJ (2003) Nutrient uptake by coral-reef microatolls. Coral Reefs 22:197–204

Storlazzi CD, Field ME, Cheriton OM, Presto MK, Logan JB (2013) Rapid fluctuations in flow and water-column properties in Asan Bay, Guam: implications for selective resilience of coral reefs in warming seas. Coral Reefs 32:949–961

Swart PK (1983) Carbon and oxygen isotope fractionation in scleractinian corals: a review. Earth Sci Rev 19:51–80

Swart PK, Saied A, Lamb K (2005) Temporal and spatial variation in the δ15 N and δ13C of coral tissue and zooxanthellae in Montastraea faveolata collected from the Florida reef tract. Limnol Oceanogr 50:1049–1058

Tremblay P, Maguer JF, Grover R, Ferrier-Pagès C (2015) Trophic dynamics of scleractinian corals: stable isotope evidence. J Exp Biol 218:1223–1234

Valiela I (1984) Marine ecological processes. Springer, New York

Williams GJ, Smith JE, Conklin EJ, Gove JM, Sala E, Sandin SA (2013) Benthic communities at two remote Pacific coral reefs: effects of reef habitat, depth, and wave energy gradients on spatial patterns. PeerJ 1:e81

Wolanski E, Delesalle B (1995) Upwelling by internal waves, Tahiti, French Polynesia. Cont Shelf Res 15:357–368

Wyatt AS, Falter JL, Lowe RJ, Humphries S, Waite AM (2012) Oceanographic forcing of nutrient uptake and release over a fringing coral reef. Limnol Oceanogr 57:401–419

Wyatt AS, Lowe RJ, Humphries S, Waite AM (2013) Particulate nutrient fluxes over a fringing coral reef: source-sink dynamics inferred from carbon to nitrogen ratios and stable isotopes. Limnol Oceanogr 58:409–427

Wyman KD, Dubinsky Z, Porter JW, Falkowski PG (1987) Light absorption and utilization among hermatypic corals: a study in Jamaica, West Indies. Mar Biol 96:283–292

Young HS, McCauley DJ, Dunbar RB, Dirzo R (2010) Plants cause ecosystem nutrient depletion via the interruption of bird-derived spatial subsidies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:2072–2077

Acknowledgements

Permission to work within Palmyra Atoll National Wildlife Refuge was granted by a Special Use Permit (SUP 12533-13025) issued by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). We thank the USFWS and The Nature Conservancy for providing logistical support, Stephen Monismith, Robert Dunbar and David Koweek for providing additional temperature data, and Mattias Green for constructing Fig. 1b. Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Stanford University are members of the Palmyra Atoll Research Consortium (PARC). This is PARC publication number PARC-TBD

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GJW and SAS conceived the project; GJW led the writing with SAS; GJW, SAS, BJZ, KAF, JMG, JSR, ZRC, NNP and JES collected data; GJW, MDF, KAF and ACH performed the lab work; GJW, JMG, and JSR analysed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Research involving animals

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: R. Hill.

Reviewed by undisclosed experts.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, G.J., Sandin, S.A., Zgliczynski, B.J. et al. Biophysical drivers of coral trophic depth zonation. Mar Biol 165, 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3314-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-018-3314-2