Abstract

Leisure well-being is satisfaction in leisure life in a manner that contributes to subjective well-being. We develop a theory of leisure well-being that explains how leisure activities contribute to leisure well-being and ultimately quality of life. Leisure activity contributes to leisure well-being by satisfying a set of basic needs (benefits related to safety, health, economic, sensory, escape, and/or sensation/stimulation needs) and growth needs (benefits related to symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, and/or distinctiveness needs). These effects are further amplified when the benefits of leisure activities match corresponding personal characteristics, namely safety consciousness, health consciousness, price sensitivity, hedonism, escapism, sensation seeking, status consciousness, aestheticism, moral sensitivity, competitiveness, sociability, and need for distinctiveness, respectively (This chapter is adapted and modified from a forthcoming publication: Sirgy, M. J., Uysal, M., & Kruger, S. (2017). Towards a benefits theory of leisure well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life 12(1), 205–228 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9482-7))

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Past research has linked leisure activities (e.g., visiting family and friends, playing sports, watching television, listening to the radio, taking tourist trips, walking for pleasure, camping, making art, and/or using the internet) with subjective well-being (e.g., Andrews and Withey 1976; Balatsky and Diener 1993; Campbell et al. 1976; Headey et al. 1991; Jackson 2008; Koopman-Boyden and Reid 2009; McGuire 1984; Menec and Chipperfield 1997; Mitas 2010; Reynolds and Lim 2007; Yarnal et al. 2008). Despite of the plethora of research in this area, the question remains: How do leisure activities enhance subjective well-being? The research literature points to several theories, namely include flow (e.g., Cheng and Lu 2015; Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre 1989) disengagement theory (e.g., Dong et al. 2014; Lapointe and Perreault 2013; Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Sonnentag and Zijlstra 2006), self-determination theory (e.g., Conway et al. 2015; Ryan and Deci 2000), goal theory (Kruger et al. 2015), and bottom-up spillover theory (e.g., Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Grzeskowiak et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2015; Kuykendall et al. 2015; Newman et al. 2014; Zuzanek and Zuzanek 2014).

Our focus here is to use bottom-up spillover theory of life satisfaction to build a theory of leisure well-being (see Sirgy 2012 for a discussion of the subjective well-being research dominated by this theory). Specifically, we introduce 12 sets mechanisms that impact satisfaction with leisure life and subjective well-being (i.e., leisure well-being): leisure benefits related to safety, health, economic, hedonic, escape, sensation-seeking, symbolic, aesthetics, morality, mastery, relatedness, and distinctiveness. We theorize that the a leisure activity contributes to leisure well-being if it meets certain basic needs (benefits related to safety, health, economic, sensory, escape, and/or sensation/stimulation needs) and certain growth needs (benefits related to symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, and/or distinctiveness needs). We also theorize that amplification occurs when certain benefits of leisure activities match corresponding personality traits: safety consciousness, health consciousness, price sensitivity, hedonism, escapism, sensation seeking, status consciousness, aestheticism, moral sensitivity, competitiveness, sociability, and need for distinctiveness, respectively (cf. Driver et al. 1991; Edginton et al. 2005; Liu 2014; Mayo and Jarvis 1981).

2 The Theory

Our theory of leisure well-being is heavily influenced by concepts from Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs, Schwartz’s (1994) value taxonomy, Inglehart’s (2008) value system, Deci and Ryan’s (2010) self-determination theory of motivation, and Murray (1938) individual needs. Hence, our theory reflects theoretical notions related to how a leisure activity is motivated by a set of benefits as reflected in the seminal works of Deci/Ryan, Inglehart, Maslow, Murray, and Schwartz.

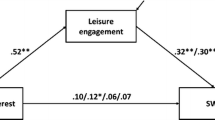

We believe that every leisure activity is associated with certain goals--benefits related to basic needs (safety, health, economic, hedonic, escape, and sensation-seeking) as well as growth needs (symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, and distinctiveness benefits). The central tenet of the theory is that a leisure activity contributes significantly to leisure well-being if it delivers a range of benefits related to both basic and growth needs (see Fig. 1.1)—the more a leisure activity delivers benefits related to basic and growth needs the greater the likelihood that such an activity would contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being (i.e., leisure well-being) (cf. Lee et al. 2014).

The psychological mechanism linking perceived benefits from a leisure activity and satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being can be explained using bottom-up spillover theory (e.g., Neal et al. 1999; Newman et al. 2014; Ragheb and Griffith 1982). The theory asserts that satisfaction with a specific leisure activity contributes to satisfaction in leisure life, which in turn contributes to subjective well-being. This is a psychological process involving a satisfaction hierarchy in which satisfaction related to a specific life event influences satisfaction with certain life domains, which in turn influences life satisfaction overall. Life satisfaction (or subjective well-being) is viewed to be a satisfaction construct on top of the satisfaction hierarchy; satisfaction in leisure life (as well satisfaction in other life domains such as social life, work life, family life, love life, community life, financial life) is considered to be less abstract. Hence, satisfaction in life domains (leisure life being a salient life domain) directly influences subjective well-being—a process characterized as bottom-up spillover. Similarly, satisfaction with a specific life event (e.g., leisure activity) is considered to be most concrete—bottom of the satisfaction hierarchy. Satisfaction with a life event influences domain satisfaction, which in turn influences subjective well-being (see a full description of this theory in Sirgy 2012).

We categorize the benefits related to a leisure activity in terms of basic versus growth needs (Maslow 1970). Leisure benefits related to basic needs include safety, health, economic, hedonic, escape, and sensation-seeking benefits. In contrast, leisure benefits related to growth needs include symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, and distinctiveness benefits. We will discuss these benefits and how they contribute to leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) in the sections below.

3 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Satisfaction of Basic Needs

One can argue that leisure well-being is mostly determined by leisure activities that have value derived from benefits related to basic needs such as safety, health, economic, sensory, escape, and sensation-seeking benefits (see Fig. 1.1).

3.1 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Safety Benefits

Leisure participants most often consider the safety features of leisure activities when they make satisfaction judgments about a leisure activity after engaging that activity (Beck and Lund 1981; Briggs and Stebbins 2014; Burton 1996; Kim et al. 2016; Mutz and Műller 2016; Pachana 2016). According to Maslow (1970), safety is a basic need. A leisure activity that meets the individual’s safety needs is likely to generate feelings of security and confidence that may result in satisfaction with the activity (cf. Chitturi et al. 2008). Formally stated, leisure well-being derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception that the activity is safe. As such, increased safety benefits associated with a leisure activity (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be safe because the players are required to wear protective eyewear) should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

We can add another personality factor that can further interact with perceived safety of the leisure activity, namely safety consciousness (e.g., Best et al. 2016; Forcier et al. 2001; Habib et al. 2014; Roult et al. 2016; Visentin et al. 2016; Westaby and Lee 2003). That is, leisure participants are likely to vary along safety consciousness. Those who might be highly safety-conscious and perceive the leisure activity to be unsafe are not likely to experience significant gains in leisure well-being. In other words, we believe that there is an interaction effect between perceived safety and safety consciousness on leisure well-being.

3.2 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Health Benefits

Leisure participants also consider the health benefits of leisure activities when they make judgments about a leisure activity before and after engagement (e.g., Blank et al. 2015; Careless and Douglas 2016; Chen et al. 2016; Davidson et al. 2016; Iwasaki and Smale 1998; Sato et al. 2014). For example, having played a good game of racquetball, the racquetball player may experience leisure satisfaction if the individual perceives significant health benefits accrued from playing the game. How many calories were lost? Increases in muscle tone? Benefits to the cardiovascular system? Etc. That is, perceived health benefits should contribute to satisfaction with the leisure activity.

Past research suggests a positive relationship between leisure activities that have health benefits and subjective well-being. For example, Newman et al. (2014) found detachment-recovery (a health-related feature of leisure activities) to promote leisure well-being. Another study (Nimrod et al. 2012) found that individuals with depression perceive leisure as a coping mechanism. Yet the more depressed they are, the less time is spent on leisure activities and the less time spent on leisure activities the more depressed they become. In a cross-sectional study among Spanish university students, Molina-Garcĭa et al. (2011) found that male and female students who are more involved in higher-level physical, leisure activities experience higher levels of psychological well-being.

Additionally, some people are more health conscious than others (e.g., Careless and Douglass 2016; Chang 2016; Iwasaki and Smale 1998; Stathi et al. 2002). If so, then one can easily argue that leisure activities perceived to be produce health benefits are likely to contribute significantly to leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) for health-conscious than nonhealth-conscious individuals.

3.3 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Economic Benefits

Economic needs are also involved in satisfaction judgments of leisure activities. Leisure participants may ask themselves whether the leisure activity is justified by the money spent (acquisition utility), as well as whether the money spent on the activity is a good deal compared with the expected cost (transactional utility) (Thaler 1985; Urbany et al. 1997). Thus, individual’s economic evaluation of a leisure activity is closely linked with their perceptions of the value of the activity (Sweeney and Soutar 2001). Formally stated, satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being (i.e., leisure well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s ability to deliver economic value (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives the fact that playing the game is indeed very affordable). As such, increased economic benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life affecting subjective well-being (cf. Brown et al. 2016; Fox 2012).

Additionally, some leisure participants are more financially frugal than others (Bove et al. 2009; Eakins 2016; Lusmägi et al. 2016). If so, then one can easily argue that leisure activities that have significant economic benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being (i.e., leisure well-being) for financially frugal than non-frugal individuals.

3.4 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Sensory Benefits

Sensory benefits and lack thereof are essentially related to basic needs. Leisure participants evaluate leisure activities on the basis of the extent to which the activity influences their sensory organs—their sense of sight, sound, touch, or scent (e.g., Wakefield and Barnes 1997). For example, activities such as sun bathing, wine tasting, and fine dining impact one’s physical senses positively (Carruthers and Hood 2004). In contrast, playing a game of billiards in a dungeon that is damp, full of cigarette smoke, and disgusting rest rooms may be noxious to the individual.

Thus, one can argue that leisure well-being (satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s ability to please one’s physical senses. As such, decreased sensory benefits associated with a leisure activity (e.g., a person playing racquetball in a racquetball court that has not been swept and cleaned) should also decrease positive affect and increase negative affect in leisure life (Briggs and Stebbins 2014; Oliveira and Doll 2016; Weng and Chang 2014).

Additionally, some people are more sensory-oriented than others (Agapito et al. 2014; Amerine et al. 2013; Ericsson and Hastie 2013; Wakefield and Barnes 1997). As such, leisure activities that lack in sensory appeal s are not likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for the sensory-types than non-sensory individuals.

3.5 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Escape Benefits

Much research in personality-social psychology has demonstrated that people are motivated to avoid noxious stimuli through leisure activities (e.g., Iso-Ahola 1980; Prebensen et al. 2012; Snepenger et al. 2006). Leisure activities allow them to get away from the stresses and strains from work, family, or whatever these sources of noxious stimuli. Unger and Kernan (1983) have identified six aspects of leisure activities that contribute to satisfaction: freedom from control, freedom from work, involvement, arousal, mastery, and spontaneity. Focusing on two of their six dimensions, freedom from control refers to “something one perceives as voluntary, without coercion or obligation” (Unger and Kernan 1983, p. 383). Freedom from work refers to the ability to rest, relax, and have no obligation to perform work-related tasks (cf. Sonnentag 2012). These two types of freedom contribute to satisfaction in different ways; some individuals may play golf to escape work, whereas others do so because golfing represents time away from work supervision. Neulinger (1981) posits that perceived freedom is a state in which the person feels that what she or he is doing is done by choice and because one wants to do it (p. 15). Suggestive evidence from past research supports this concept. For example, a study by Lapa (2013) found significant differences between leisure satisfaction and perceived freedom based on age and income, perceived freedom and gender, and a positive linear relationship between life satisfaction and leisure satisfaction among park recreation participants. As such we theorize that subjective well-being derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s ability to deliver freedom and escape benefits (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be scheduled at times when he or she can escape from the job for an hour or two). Increased freedom/escape benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

Furthermore, some people have a greater proclivity to seek out leisure activities with freedom/escape benefits than others (Hallman et al. 2014; Haraszti et al. 2014; Lusby and Anderson 2010). If so, then one can easily argue that leisure activities that have significant freedom/escape benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for individuals with a greater proclivity for freedom and escape than those with a lesser proclivity.

3.6 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Sensation-Seeking Benefits

Much research in personality-social psychology has demonstrated that people are motivated to seek stimulation through leisure activities (e.g., Argyle 1997). Examples of such activities include children’s interest in leisurely reading outside of school hours (e.g., Jensen et al. 2011), optimal experiences in river racing (e.g., Shih and Chen 2013), leisure boredom and adolescent risk behaviors (e.g., Wegner and Flisher 2009), white-water rafting (e.g., Chen and Chen 2010), skydiving (e.g., Myrseth et al. 2012), and bungee jumping (McKay 2014).

We argue that leisure activities with sensation-seeking benefits tend to contribute to subjective well-being. Activity theory may shed some light on the why question. Much research has shown that the greater the frequency of participation in leisure activities among the elderly the higher the subjective well-being (e.g., Adams et al. 2011; Janke and Davey 2006; Lemon et al. 1972). Activities tend to make people feel alive and well. Hence, we can assert that leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s ability to deliver much stimulation and thrill (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be highly stimulating because he or she is playing against a tough opponent). As such, increased stimulation/thrill benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

Additionally, some people are more sensation-seeking than others (e.g., Laviolette 2012; Sotomayor and Barbieri 2016; Zuckerman 1969, 1971, 2007). Zuckerman (1969, 1971, 2007) and Zuckerman and Aluja (2014) proposed the theory of “sensation seeking” involving sensory deprivation based on optimal level of stimulation. The sensation seeking scale includes 50 items that capture ideal levels of stimulation or sensory arousal based on behavioral, social and thrill-seeking types of activities. Zuckerman (2007) found that those who pursue dangerous sports tend to be sensation seekers. People who are high on sensation seeking tend to engage in high risk behaviors of all kinds. As such, we theorize that leisure activities that have significant stimulation/thrill benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for sensation-seeking than non-sensation seeking individuals.

4 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Satisfaction of Growth Needs

Leisure scholars argue that participating in leisure activities serves as a medium for personal enhancement and self-development—offers the opportunity to realize one’s potential for lasting fulfilment (e.g., Filep 2012; Kelly 1990; Kleiber 1999; Kuentzel 2000; Murphy 1974; Stebbins 1992, 1996, 2005, 2012). In other words, engaging in meaningful and purposeful leisure activities yields rewards that encompass self- actualization, self-enrichment, self-exploration, and self-gratification, and as such these rewards can be viewed as growth or higher-order needs (Hall and Weiler 1992). However, different forms and types of leisure lead to different outcomes and life enriching experiences. Robert A. Stebbins (2015), in his pioneering work on “serious leisure,” classified leisure activities into three forms of leisure: serious, casual, and project-based leisure. He argues that leisure participants can achieve a sense of well-being while partaking in leisure activities whether these activities are serious pursuits, casual, or project based depending on the context in which leisure activities are experienced. For example, a number of studies in leisure and tourism reveal that a growing number of people who travel engage in leisure activities in order to seek challenges, co-create experiences, and also demonstrate creativity (cf. Filep 2008; Long 1995; Stebbins 1996; Thomas and Butts 1988; Wang and Wong 2014). Feelings of achievement and mastery are quite important for leisure participants and much research support this assertion (e.g., Beard and Ragheb 1980; Vitterso 2004; White and Hendee 2000). Thus, benefits realized from leisure activities do lead to the development of competency and skill mastery, personal development, and growth, reflecting states of self- actualization and self-enrichment, which in turn contribute to subjective well-being (e.g., Gilbert and Abdullah 2004; Dolnicar et al. 2012). The assertion that leisure activities can provide benefits that satisfy growth needs is consistent with several theories of human motivation, namely Maslow’s (1970) needs theory and Ryan and Deci’s (2000) self-determination theory. The extant literature supports the general theme of this paper in that every leisure activity provides functional benefits, and benefits related to basic as well as growth needs of participants as seen in Fig. 1.1. We now turn our attention to describing leisure benefits related to growth needs—symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, and distinctiveness benefits.

4.1 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Symbolic Benefits

The benefits that reflect self (or symbolic) needs relate directly to social approval, such that individuals evaluate leisure activities according to the extent to which those activities symbolize their social self (Maslow 1970). For example, people might wonder, “Does this leisure activity bestow status and prestige on me?” or “Are others impressed when they see me engaged in this activity?” The underlying need here is social approval (Sirgy 1986). The needs for self-esteem and self-consistency equally apply too (Sirgy 1982, 1986). People may question, “Does my engagement in this leisure activity help me become the kind of person I like to become?” (need for self-esteem) or “Is participation in this activity consistent with the kind of person I am?” (need for self-consistency).

Much research in consumer behavior has shown that consumers purchase goods to express their identity (e.g., Attanasio et al. 2015; Malhotra 1988; Sirgy 1982), and self-congruity plays an important role in pre-purchase behaviors (e.g., brand attitude, brand preferences, purchase motivation, brand choice), as well as post-consumption responses (e.g., consumer satisfaction, brand loyalty, repeat purchase). The same research applies to leisure activities and leisure well-being (Sirgy and Su 2000). How? Based on self-congruity theory (Sirgy 1986), each leisure activity is associated with a personality. For example, a person who enjoys fishing may have a calm demeanor, a person who enjoys racquetball is competitive, a person who plays chess is intellectual, etc. Thus, people feel satisfied with a leisure activity when they perceive the personality associated with a leisure activity matching their own actual self-image. Such satisfaction is motivated by the need for self-consistency. That is, people feel good about activities they participate because the activities serve to reinforce their personal identity. For example, if a person is an intellectual and has an image of a typical chess player as being intellectual, then playing a chess game serves to reinforce his image of being intellectual. This is self-validation making the person feel happy about the fact that he is playing chess. The same can be said in relation to the ideal self and social self (Snyder and DeBono 1985). People like to project positive images of themselves in the eyes of others (particularly significant others), and they may do this by engaging in leisure activities that are associated with those images. Doing so is motivated by the needs for self-esteem and social approval. For example, the image of a person who is a marathon runner is that of an athlete who can persevere through much pain and has much self-control. A person decides to participate in a marathon. He or she wants to become a person who exercises a high degree of self-control (ideal self-image); he or she wants to convince others that is a person who exercises a high degree of self-control (social self). Engaging in a marathon run is likely to be satisfying because the activity would meet the need for self-esteem (allow him or her to realize an ideal self-image) and the need for social approval (allow others to think of him or her as a person who has a high degree of self-control).

Formally stated, leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be played with other players he or she can identify with—players like him of her) is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s symbolic value to reinforce and validate actual, ideal, and social self-image. As such, increased symbolic benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect (Abbott-Chapman and Robertson 2015; Ekinci et al. 2013; Funk and James 2015; Shim et al. 2013; Sirgy 1982, 1986; Sirgy and Su 2000).

Additionally, some people are more self-expressive than others (e.g., Lee et al. 2015; Bosnjak et al. 2016; Waterman et al. 2008). As such, we theorize that leisure activities that have significant symbolic benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for self-expressive than non-self-expressive individuals.

4.2 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Benefits Related to Beauty and Aesthetics

Maslow (1970) also describes the need for beauty or aesthetics. This need may be involved in satisfaction judgments of leisure activities. In other words, leisure participants evaluate leisure activities on the basis of the extent to which the activity satisfies their sense of beauty and aesthetics. Consider leisure activities such visiting an art gallery, attending a musical concerto, taking a sculpture or pottery workshop, painting of fine arts, etc. (Hasmi et al. 2014; Lehto et al. 2014; Stranger 1999).

Thus, we theorize that subjective well-being derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s aesthetic and beauty value. As such, increased aesthetic/beauty benefits associated with a leisure activity or its environment (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be played in an aesthetically pleasing court) should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

Additionally, some people are more aesthetics-oriented than others (e.g., Abuhamdeh and Csikszentmihalyi 2004). If so, then one can argue that leisure activities that have significant aesthetics/beauty benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for those who are more aesthetics-oriented than those who are less so.

4.3 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Moral Benefits

We also introduce the concept of moral benefits based on Maslow’s (1970) need for self-actualization and self-transcendence, as developed further by Schwartz (1994), and Inglehart (2008). Maslow (1970) describes a self-actualized person as integrated socially, emotionally, cognitively, and morally, such that he or she engages in moral reasoning and evaluates courses of action on the basis of moral criteria. Leisure participants may evaluate leisure activities according to whether participation in those activities contributes to the welfare of others (e.g., relay events to raise funds for a group or community in need) (Godbey et al. 2005).

Thus, we argue that leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s moral benefits (e.g., a racquetball player who usually plays the game for leisure purposes signs up in a racquetball tournament sponsored by a charity organization such as the UNICEF—ticket proceeds used directly to support children and youth programs in developing countries). As such, increased moral benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life (e.g., Anić 2014; Long et al. 2014; Sylvester 2015).

Additionally, some leisure participants are more morally sensitive than others (e.g., Myyry and Helkama 2002). If so, then one can argue that leisure activities that have significant moral benefits are likely to contribute significantly to leisure well-being for the morally-sensitive than the morally non-sensitive individuals.

4.4 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Mastery Benefits

Unger and Kernan (1983) have identified mastery as an important driver of leisure activities. Leisure activities that allow people to experience feelings of mastery induce much positive affect. An individual might feel a sense of mastery after completing the ultimate level of a challenging video game. Suggestive evidence from research in subjective well-being supports this relationship (Newman et al. 2014; Sonnentag and Fritz 2007). For example, Chang and Yu (2013) was able to demonstrate that leisure competence is negatively related to health-related stressors for older adults living in Taiwan.

Mastery benefits in leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being. Perhaps this occurs through effectance motivation (Hills and Argyle 2001; Hills et al. 2000). Respondents were asked to rate their ability in relation to 36 activities: “How good do you think you are at this activity?” The study results indicated that reported enjoyment activities correlated highly with reported ability for all activities, even for activities that do not seem to involve effectance (e.g., watching television, reading a book, and going for a walk). Mastering leisure activities make people feel useful and productive. Through mastering leisure activities people experience rewards of all kinds: social rewards (e.g., Twenge et al. 2010), a sense of recognition, and in some cases monetary rewards (e.g., Tapps et al. 2013).

We believe that leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s mastery benefits (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be helpful in enhancing his or her skill level in racquetball-related sports). As such, increased mastery benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

There may be individual differences here too. That is, some people are more mastery-seeking than others (e.g., Dweck and Leggett 1988; Forbes 2015). If so, leisure activities that have significant mastery benefits are likely to contribute significantly to subjective well-being for mastery-seeking than non-mastery-seeking individuals.

4.5 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Relatedness Benefits

Many leisure activities (e.g., watching a movie drama, playing tennis, engaging in team sports, getting together with others in church or social clubs) are social in nature. That is, they involve people socializing while engaging in leisure--social interactions that result in satisfaction of a variety of social needs. Examples of social needs include the need for social approval, affiliation, belongingness, social status, social recognition, cooperation, competition, and altruism (e.g., Brajsa-Zganec et al. 2011; Leung and Lee 2005).

Suggestive evidence from research in subjective well-being supports this relationship (Deci and Ryan 2010; Newman et al. 2014). For example, Chang and Yu (2013) demonstrated that leisure social support is negatively related to health-related stressors for older adults living in Taiwan.

Relatedness benefits in leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being by satisfying social needs, an important ingredient in subjective well-being. Consider the following study conducted by Hills et al. (2000). The study demonstrated the link between leisure activities and satisfaction of social needs. Specifically, satisfaction of social needs was significantly correlated with the following activities:

-

Engaging in active sports, taking on dangerous sports, fishing, and attending musical performance (r = .27);

-

Dancing, eating out, engaging in family activities, attending social parties, getting together with other people at pubs, travelling to tourist places on holidays, socializing with friends, going to the movies, and watching sport events (r = .45);

-

Engaging in do-it-yourself activities, taking evening classes, doing meditation, engaging in serious reading, and sewing (r = .46);

-

Attending political activities, raising money for charity, engaging in religious activities, and doing voluntary work (r = .55).

Thus, we believe that leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s relatedness benefits (e.g., a person playing racquetball for leisure perceives a specific game to be played in the context of a social club allowing him or her to socialize with others before and after the game). As such, increased relatedeness benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect. Additionally, some people are more extroverted than others (e.g., Caldwell and Andereck 1994; Walker et al. 2005).

We also believe that this relation is moderated by extroversion-introversion. That is, leisure activities that have significant relatedness benefits are likely to contribute significantly to subjective well-being for extroverts more so than for introverts.

4.6 Leisure Well-Being Derived from Distinctiveness Benefits

There is a tendency in people to desire uniqueness. Striving for uniqueness is wired in us. As such, this motive is manifested in participating in leisure activities and hedonic consumption (Frochota and Morrison 2001; Tinsley and Tinsley 1986). Engaging in leisure activities considered less common or less popular is usually a way to demonstrate uniqueness—observers are likely to perceive the actor as highly distinct—standing out from the crowd.

We believe that leisure well-being (i.e., satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being) derived from a leisure activity is a positive function of the individual’s perception of the activity’s distinctiveness benefits (e.g., a college student may perceive squash as a game played by a select few, thus chooses to play squash because doing so is likely to make him or her highly distinct from other college students). As such, increased distinctiveness benefits associated with a leisure activity should also increase positive affect and decrease negative affect in leisure life.

Additionally, some people seek distinctiveness more than others (e.g., Abbott-Chapman and Robertson 2015). In other words, we believe that the uniqueness benefit effect on subjective well-being is moderated by a personality trait related to seeking distinctiveness. Leisure activities that have significant distinctiveness benefits are likely to contribute significantly to satisfaction in leisure life and subjective well-being for those seek distinctiveness than those who do not.

5 Conclusion

In this chapter we discuss a theory of leisure well-being guided by the concept of bottom-up spillover (e.g., Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Newman et al. (2014). The goal is to introduce to the reader a more-refined bottom-up spillover model by linking 12 sets of perceived leisure benefits to subjective well-being—leisure benefits related to safety, health, economic, sensory, escape, sensation-seeking, symbolic, aesthetics, morality, mastery, relatedness, and distinctiveness. We argued that the perceived benefits can be categorized in terms of basic versus growth needs. Benefits associated with basic needs include benefits related to safety, health, economic, sensory, escape, or sensation/stimulation needs. In contrast, benefits related to growth needs include benefits related to symbolic, aesthetic, moral, mastery, relatedness, or distinctiveness needs. We argue that the satisfaction that is extracted as a result of the leisure activity’s interaction between benefits related to basic and growth needs is further amplified when the same benefits match the individual’s personality. This satisfaction amplification associated with the leisure activity contributes significantly to positive affect in leisure life, which in turn contributes significantly to subjective well-being.

Although we provided suggestive evidence to our theoretical propositions, we believe that the theory can set the stage for programmatic research in this area. We encourage leisure researchers to conduct rigorous research to systematically test the theoretical propositions through cross-sectional surveys and longitudinal research. Such testing should lead to the transformation of the overall model into an established theory of leisure well-being.

Our theory of leisure well-being has several managerial implications. The theory prompts leisure professionals to do the following:

-

Any leisure activity should be planned to provide benefits related to basic needs: benefits related to safety (safety measures are taken such wearing of protective eyewear), health (the game enhances cardio-vascular health and helps with weight control), economics (the service fee is affordable), sensory (after the game the patrons enjoy a soothing massage followed by a hot shower and a delicious snack), escape (the game is scheduled mid-day to allow the patrons to temporarily escape the stress of their job), and/or sensation/stimulation (the game allows the patrons to experience a high level of sensation/stimulation perhaps by matching players with competitors of equal skill level).

-

Additionally, the leisure activity should also be planned to provide benefits related to growth needs: benefits related to the self (the patrons can identify with one another, perhaps in terms of age, gender, and occupational status—mature men who are professors playing racquetball at the same college), aesthetics (the racquetball courts are aesthetically pleasing), morality (the game is sponsored by a charity organization), mastery (a racquetball mentor oversees the game to provide tips and guidance to foster performance excellence), relatedness (the game is offered through a social club to allow players to socialize before and after the game), and/or distinctiveness (each play is encouraged to develop his or her own winning strategies and to share this knowledge with selected others).

-

In addition to ensuring benefits related to the patron’s basic and growth needs, the leisure activity should also be planned to ensure that the satisfaction effect from the inherent benefits related to basic and growth needs are further amplified by matching the leisure activity to patrons with corresponding personality traits (i.e., personality traits that reflect the selected basic and growth needs). For example, a benefit such as relatedness can be injected in the planning of the leisure activity if management knows that most of the patrons are extroverts. Hence, the extrovert racquetball players are likely to experience a higher level of satisfaction playing the game in the context of a social club to allow them to socialize before and after the game.

References

Abbott-Chapman, J., & Robertson, M. (2015). Youth leisure, places, spaces and identity. In Landscapes of leisure (pp. 123–134). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Abuhamdeh, S., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2004). The artistic personality: A systems perspective. In R. J. Sternberg, E. L. Grigorenka, & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Creativity: From potential to realization (pp. 31–42). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Adams, K. B., Leibbrandt, S., & Moon, H. (2011). A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing and Society, 31, 683–712.

Agapito, D., Valle, P., & Mendes, J. (2014). The sensory dimension of tourist experiences: Capturing meaningful sensory-informed themes in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 42, 224–237.

Amerine, M. A., Pangborn, R. M., & Roessler, E. B. (2013). Principals of sensory evaluation of food. London: Elsevier.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum Press.

Anić, P. (2014). Hedonic and eudaimonic motives for favourite leisure activities. Primenjena Psihologija, 7, 5–21.

Argyle, M. (1997). Subjective well-being. In A. Offer (Ed.), In pursuit of the quality of life. Oxford: Clarendon Press Oxford.

Attanasio, O., Hurst, E., & Pistaferri, L. (2015). The evolution of income, consumption, and leisure inequality in the United States. In C. D. Carrol & T. F. Crossley (Eds.), Improving the measurement of consumer expenditures. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Balatsky, G., & Diener, E. (1993). Subjective well-being among Russian students. Social Indicators Research, 28, 225–243.

Beard, J. G., & Ragheb, M. G. (1980). Measuring leisure satisfaction. Journal of Leisure Research, 12, 20–33.

Beck, K. H., & Lund, A. K. (1981). The effects of health threat seriousness and personal efficacy upon intentions and behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 11, 401–415.

Best, K., Miller, W. C., Huston, G., Routhier, F., & Engg, J. J. (2016). Pilot study of a peer-led wheelchair training program to improve self-efficacy using a manual wheelchair: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 97(2), 37–44.

Blank, C., Leichtfried, V., Schobersberger, W., & Möller, C. (2015). Does leisure time negatively affect personal health? World Leisure Journal, 57(2), 1–6.

Bosnjak, M., Brown, C. A., Lee, D. J., Grace, B. Y., & Sirgy, M. J. (2016). Self-expressiveness in sport tourism: Determinants and consequences. Journal of Travel Research, 55, 125–134.

Bove, L. L., Nagpal, A., & Dorsett, S. A. D. (2009). Exploring the determinants of the frugal shopper. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 16, 291–297.

Brajša-Žganec, A., Merkaš, M., & Šverko, I. (2011). Quality of life and leisure activities: How do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 102, 81–91.

Briggs, D., & Stebbins, R. (2014). Solo ice climbing: An exploration of a new outdoor leisure activity. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 6, 55–67.

Brown, V., Diomedi, B. Z., Moodie, M., Veerman, J. L., & Carter, R. (2016). A systematic review of economic analyses of active transport interventions that include physical activity benefits. Transport policies, 45, 190–208.

Burton, I. T. (1996). Safety nets and security blankets: False dichotomies in leisure studies. Leisure Studies, 15, 17–30.

Caldwell, L. L., & Andereck, K. (1994). Motives for initiating and continuing membership in a recreation-related voluntary association. Leisure Sciences, 16, 33–44.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Careless, D., & Douglas, K. (2016). The Bristol active life project: Physical activity and sport for mental health. In Sports-based health interventions (pp. 101–115). New York: Springer.

Carruthers, C., & Hood, C. D. (2004). The power of the positive: Leisure and well-being. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 38, 225–245.

Chang, H. H. (2016). Gender differences in leisure involvement and flow experiences in professional extreme sport activities. World Leisure Journal, 59, 1–16.

Chang, L. C., & Yu, P. (2013). Relationships between leisure factors and health-related stress among older adults. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 18, 79–88.

Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31, 29–35.

Chen, C. C., Hyang, W. J., & Petrick, J. F. (2016). Holiday recovery experiences, tourism statisfaction – Is there a relationship? Tourism Management, 53, 140–147.

Cheng, T. M., & Lu, C. C. (2015). The causal relationships among recreational involvement, flow experience, and well-being for surfing activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20, 1–19.

Chitturi, R., Raghunathan, R., & Mahajan, V. (2008). Delight by design: The role of hedonic versus utilitarian benefits. Journal of Marketing, 72, 48–63.

Conway, N., Clinton, M., Sturges, J., & Budjanovcanin, A. (2015). Using self-determination theory to understand the relationship between calling enactment and daily well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2014.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 815–822.

Davidson, C., Ewert, D., & Chang, Y. (2016). Multiple methods for identifying outcomes of a high challenge adventure activity. The Journal of Experimental Education., published online, 39(2), 164–178.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Self-determination. New York: Wiley.

Dolnicar, S., Yanamandram, V., & Cliff, K. (2012). The contribution of vacations to quality of life. Annals of Tourism Research, 39, 59–83.

Dong, X., Li, Y., & Simon, M. A. (2014). Social engagement among US Chinese older adults—Findings from the PINE study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S82–S89.

Driver, B. L., Brown, P. J., & Peterson, G. L. (1991). Benefits of leisure. State College: Venture Publishing.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273.

Eakins, J. (2016). An examination of the determinants of Irish household sports expenditures and the effects of the economic recession. European Sport Management Quarterly, 6, 86–105.

Edginton, C., DeGraaf, D., Dieser, R., & Edginton, S. (2005). Leisure and life satisfaction: Foundational perspectives. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

Ekinci, Y., Sirakaya-Turk, E., & Preciado, S. (2013). Symbolic consumption of tourism destination brands. Journal of Business Research, 66, 711–718.

Ericsson, K. A., & Hastie, R. (2013). Contemporary approaches to the study of thinleing and problem-solving. Thinking and Problem Solving, 2, 37–50.

Filep, S. (2008). Applying the dimensions of flow to explore visitor engagement and satisfaction. Visitor Studies, 11, 90–108.

Filep, S. (2012). Positive psychology and tourism. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of tourism and quality-of-life research: Enhancing the lives of tourists and residents of host communities (pp. 31–50). Dordrecht: Springer.

Forbes, D. (2015). The mastery motive. In The science of why (pp. 93–109). Palgrave Macmillan US.

Forcier, B. H., Walters, A. E., Brasher, E. E., & Jones, J. W. (2001). Creating a safer working environment through psychological assessment: A review of a measure of safety consciousness. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 22, 53–65.

Fox, J. (2012). The economics of well-being. Harvard Business Review, 90, 78–83.

Frochota, I., & Morrison, M. A. (2001). Benefit segmentation: A review of its applications to travel and tourism research. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 9, 21–45.

Funk, D. C., & James, J. D. (2015). An evolutionary perspective. Routledge handbook of theory in sport management, 247.

Gilbert, D., & Abdullah, J. (2004). Holiday-taking and the sense of well-being. Annals of Tourism Research, 31, 103–121.

Godbey, C., Caldwell, L., Floyd, M., & Payne, L. L. (2005). Contributions of leisure studies and recreation and park management research to the active living agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 150–158.

Grzeskowiak, S., Lee, D. J., Grace, B. Y., & Sirgy, M. J. (2014). How do consumers perceive the quality-of-life impact of durable goods? A consumer well-being model based on the consumption life cycle. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9, 683–709.

Habib, K. N., Mann, J., Mahmoud, M., & Weiss, A. (2014). Synopsis of bicycle demand in the City of Toronto: Investigating the effects of perception, consciousness and comfortability on the purpose of biking and bike ownership. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 70, 67–80.

Hall, C. M., & Weiler, B. (1992). Introduction. In C. M. Hall & B. Weiler (Eds.), Special interest tourism (pp. 1–14). New York: Wiley.

Hallman, D. M., Ekman, A. H., & Lyskove, E. (2014). Changes in physical activity and heart rate variability in chronic neck-shoulder pain: Monitoring during work and leisure time. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 87, 735–744.

Haraszti, R. A., Pureble, G., Salavecz, G., Poole, L., Dockray, S., & Stetoe, A. (2014). Morningness-eveningness interfere with perceived health, physical activity diet and stress levels in working women: A cross-sectional study. Cronobiology International, 31, 829–837.

Hasmi, H. M., Gross, M. J., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2014). Leisure and settlement distress: The case of South Australian migrants. Annals of Leisure Research, 17, 377–397.

Headey, B., Veenhoven, R., & Wearing, A. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24, 81–100.

Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2001). Emotional stability as a major dimension of happiness. Personality and Individual, 31, 1357–1364.

Hills, P., Argyle, M., & Reeves, R. (2000). Individual differences in leisure satisfactions: An investigation of four theories of leisure motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 763–779.

Inglehart, R. F. (2008). Changing values among western publics from 1970 to 2006. West European Politics, 31, 130–146.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1980). Social psychological perspectives on leisure and recreation. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

Iwasaki, Y., & Smale, B. J. A. (1998). Longitudinal analyses of the relationships among life transitions, chronic health problems, leisure, and psychological well-being. Leisure Sciences, 20, 25–52.

Jackson, L. T. (2008). Leisure activities and quality of life. Activities, Adaptation, & Aging, 23, 19–24.

Janke, M., & Davey, A. (2006). Implications of selective optimization with compensation on the physical, formal and informal leisure patterns of adults. Indian Journal of Gerontology, 20, 51–66.

Jensen, J., Imboden, K., & Ivic, R. (2011). Sensation seeking and narrative transportation: High sensation seeking children's interest in reading outside of school. Scientific Studies of Reading, 15, 541–558.

Kelly, J. R. (1990). Leisure. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Kim, H., Woo, E., & Uysal, M. (2015). Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tourism Management, 46, 465–476.

Kim, M., Park, S., Park, B., Cho, Y. H., & Kang, S. Y. (2016). A new paradigm for the spread sport leisure culture focussing on the IT-based convergence interactive system. In K. Kim & N. Joukov (Eds.), Information Science and Applications (ICISA) (pp. 1477–1485). Singapore: Springer Publishers.

Kleiber, D. (1999). A dialectical interpretation: Leisure experience and human development. New York: Basic Books.

Koopman-Boyden, P. G., & Reid, S. L. (2009). Internet/e-mail usage and well-being among 65–84 years olds in New Zealand: Policy implications. Educational Gerontology, 35, 990–1007.

Kruger, S., Sirgy, M. J., Lee, D. J., & Yu, G. (2015). Does life satisfaction of tourists increase if they set travel goals that have high positive valence? Tourism Analysis, 20, 173–188.

Kuentzel, W. F. (2000). Self-identity, modernity, and rational actor in leisure research. Journal of Leisure Research, 32, 87–92.

Kuykendall, L., Tay, L., & Ng, V. (2015). Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 364–403.

Lapa, T. Y. (2013). Life satisfaction, leisure satisfaction and perceived freedom of park recreation participants. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 1985–1993.

Lapointe, M. C., & Perreault, S. (2013). Motivation: Understanding leisure engagement and disengagement. Loisir et Société/Society and Leisure, 36, 136–144.

Laviolette, P. (2012). Extreme landscapes of leisure: Not a hap hazardous sport. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Ltd..

Lee, D. J., Kruger, S., Whang, M. J., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2014). Validating a customer well-being index related to natural wildlife tourism. Tourism Management, 45, 171–180.

Lee, B., Lawson, K. M., Chang, P. J., Neuendorf, C., Dmitrieva, N. O., & Almeida, D. M. (2015). Leisure-time physical activity moderates the longitudinal associations between work-family spillover and physical health. Journal of Leisure Research, 47, 1–32.

Lehto, X. Y., Park, O., Fu, X., & Lee, G. (2014). Student life stress and leisure participation. Annals of Leisure Research, 17, 200–217.

Lemon, B. W., Bengston, V. L., & Peterson, J. A. (1972). An exploration of the activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. Journal of Gerontology, 27, 511–523.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. S. (2005). Multiple determinants of life quality: The roles of internet activities, use of new media, social support, and leisure activities. Telematics and Informatics, 22, 161–180.

Liu, H. (2014). Personality, leisure satisfaction, and subjective well-being of serious leisure participants. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42, 1117–1125.

Long, H. (1995). Outcomes of Elderhostel participation. Educational Gerontology, 21, 113–127.

Long, J., Hylton, K., & Spracklen, K. (2014). Whiteness, blackness and settlement: Leisure and the integration of new migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40, 1779–1797.

Lusby, C., & Anderson, S. (2010). Ocean cruising – a lifestyle process. Leisure/Loisir, 34, 85–105.

Lusmägi, P., Einasto, M., & Roosma, A. (2016). Leisure-time physical activity among different social groups of Estonia: Results of the national physical activity survey. Physical Culture and Sport Studies and Research, 69, 43–52.

Malhotra, N. K. (1988). Self-concept and product choice: An integrated perspective. Journal of Economic Psychology, 9, 1–28.

Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Mayo, E. J., & Jarvis, L. P. (1981). The psychology of leisure travel. Boston: CBI Publishing Company.

McGuire, F. (1984). Improving the quality of life for residents of long term care facilities through video games. Activities, Adaptation, & Aging, 6, 1–7.

McKay, T. M. (2014). Locating South Africa within the global adventure tourism industry: The case of bungee jumping. Bulletin of Geography Socio-Economic Series, 24(24), 161–176.

Menec, V. H., & Chipperfield, J. G. (1997). Remaining active in later life: The role of locus of control in seniors’ leisure activity participation, health, and life satisfaction. Journal of Aging and Health, 9, 105–125.

Mitas, O. (2010). Positive emotions in mature adults’ leisure travel experiences. Doctoral dissertation, University Park: Pennsylvania State University.

Molina-García, J., Castillo, I., & Queralt, A. (2011). Leisure-time physical activity and psychological well-being in university students. Psychological Reports, 109, 453–460.

Murphy, J. F. (1974). Concepts of leisure: Philosophical implications. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

Mutz, M., & Műller, J. (2016). Mental health benefits of outdoor adventures: Results from two pilot studies. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 105–114.

Myrseth, H., Tvera, R., Hagatun, S., & Lindgren, C. (2012). A comparison of impulsivity and sensation seeking in pathological gamblers and skydivers. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 53, 340–346.

Myyry, L., & Helkama, K. (2002). The role of value priorities and professional ethics training in moral sensitivity. Journal of Moral Education, 31, 35–50.

Neal, J., Sirgy, M., & Uysal, M. (1999). The role of satisfaction with leisure travel/tourism services and experience in satisfaction with leisure life and overall life. Journal of Business Research, 44, 153–163.

Neulinger, J. (1981). The psychology of leisure (2nd ed.). Boston: Charles C. Thomas.

Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 555–578.

Nimrod, G., Kleiber, D. A., & Berdychevsky, L. (2012). Leisure in coping with depression. Journal of Leisure Research, 44, 419–449.

Oliveira, S. N., & Doll, J. (2016). Careers in serious leisure: From dabbler to devotee in search of fulfillment. World Leisure Journal, 59, 1–3.

Pachana, N. A. (2016). Driving space and access to activity. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71, 69–70.

Prebensen, N., Woo, E., Chen, J., & Uysal, M. (2012). Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. Journal of Travel Research, 52, 253–264.

Ragheb, M. G., & Griffith, C. A. (1982). The contribution of leisure participation and leisure satisfaction to life satisfaction of older persons. Journal of Leisure Research, 14, 295–306.

Reynolds, F., & Lim, K. H. (2007). Contribution of visual art-making to the subjective well-being of women living with cancer: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34, 1–10.

Roult, R., Adjzian, J. M., Auger, D., & Royer, C. (2016). Sporting and leisure activities among adolescents: A case study of the spatial planning of the proximity of leisure and sports facilities in rural and suburban territories in Quebec. Loisir et Société and Leisure, 39, 31–45.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Sato, M., Jordan, J. S., & Funk, D. C. (2014). The role of physically active leisure for enhancing quality of life. Leisure Sciences, 36, 293–313.

Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19–45.

Shih, H. M., & Chen, S. L. (2013). A study on the sensation seeking and optimal experience of river racing participants. In 2013 fourth international conference on education and sports education (ESE 2013, pp. 465–469). Singapore Management and Sports Science Institute.

Shim, C., Santos, C. A., & Choi, M. J. (2013). Malling as a leisure activity in South Korea. Journal of Leisure Research, 45, 367.

Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 287–300.

Sirgy, M. J. (1986). Self-Congruity: Toward a theory of personality and cybernetics. New York: Praeger.

Sirgy, M. J. (2012). The psychology of quality of life: Hedonic well-being, life satisfaction, and eudaimonia. New York: Springer.

Sirgy, M. J., & Su, C. (2000). Destination image, self-congruity, and travel behavior: Toward an integrative model. Journal of Travel Research, 38, 340–352.

Snepenger, D., King, J., Marshall, E., & Uysal, M. (2006). Modelling Iso-Ahola’s motivation theory in the tourism context. Journal of Travel Research, 45, 140–149.

Snyder, M., & DeBono, K. G. (1985). Appeals to image and claims about quality: Understanding the psychology of advertising. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 586.

Sonnentag, S. (2012). Psychological detachment from work during leisure time the benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 114–118.

Sonnentag, S., & Fritz, C. (2007). The recovery experience questionnaire: Development and validation of a measure for assessing recuperation and unwinding from work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 12, 204.

Sonnentag, S., & Zijlstra, F. R. (2006). Job characteristics and off-job activities as predictors of need for recovery, well-being, and fatigue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 330.

Sotomayor, S., & Barbieri, C. (2016). An exploratory examination of serious surfers: Implications for the surf tourism industry. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18, 62–73.

Stathi, A., Fox, K. R., & McKenna, J. (2002). Physical activity and dimensions of subjective well-being in older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 10, 76–92.

Stebbins, R. A. (1992). Amateurs, professionals, and serious leisure. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Stebbins, R. A. (1996). Volunteering: A serious leisure perspective. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25, 211–224.

Stebbins, R. A. (2005). Project-based leisure: Theoretical neglect of a common use of free time. Leisure Studies, 24, 1–11.

Stebbins, R. A. (2012). The idea of leisure: First principles. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Stebbins, R. A. (2015). Serious leisure: A perspective for our time. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Stranger, M. (1999). The aesthetics of risk. International Review of the Sociology of Sport, 34, 265–276.

Sweeney, J., & Soutar, G. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77, 203–207.

Sylvester, C. (2015). With leisure and recreation for all: Preserving and promoting a worthy pledge. World Leisure Journal, 57, 76–81.

Tapps, T., Beck, S., Cho, D., & Volberding, J. (2013). Sports motivation: Three generations of college athletes. Journal of the Oklahoma Association for Health, Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 50, 43–50.

Thaler, R. (1985). Mental accounting and consumer choice. Marketing Science, 4, 199–214.

Thomas, D. W., & Butts, F. B. (1988). Assessing leisure motivators and satisfaction of international elder hostel participants. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 7, 31–38.

Tinsley, H. E. A., & Tinsley, D. J. (1986). A theory of the attributes, benefits, and causes of leisure experience. Leisure Sciences, 8, 1–45.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J., & Lance, C. E. (2010). Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. Journal of Management, 36, 1117–1142.

Unger, L. S., & Kernan, J. B. (1983). On the meaning of leisure: An investigation of some determinants of the subjective experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 9, 381–392.

Urbany, J. E., Bearden, W. O., Kaicker, A., & Smith-de Borrero, M. (1997). Transaction utility effects when quality is uncertain. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25, 45–55.

Visentin, A., de Fátima Mantovani, M., Caveião, C., Mendes, T. A., Neves, A. S., & Hey, A. P. (2016). Quality of life of an institution hypertensive older woman long stay. RENE-Revista da Rede de Engermagem do Nordeste, 16(2). Ahead of print.

Vitterso, J. (2004). Subjective well-being versus self-actualization: Using the flow simplex to promote a conceptual clarification of subjective quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 65, 299–331.

Wakefield, K. L., & Barnes, J. H. (1997). Retailing hedonic consumption: A model of sales promotion of a leisure service. Journal of Retailing, 72, 409–427.

Walker, G. J., Deng, J. Y., & Diser, R. B. (2005). Culture, self-construal, and leisure theory and practice. Journal of Leisure Research, 37, 77–99.

Wang, M., & Wong, M. C. (2014). Leisure and happiness: Evidence from international survey data. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 85–118.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., & Conti, R. (2008). The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 41–79.

Wegner, L., & Flisher, A. J. (2009). Leisure boredom and adolescent risk behaviour: A systematic literature review. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 21, 1–28.

Weng, P. Y., & Chang, Y. C. (2014). Psychological restoration through indoor and outdoor leisure activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 46, 203.

Westaby, J. D., & Lee, B. C. (2003). Antecedents of injury among youth in agricultural settings: A longitudinal examination of safety consciousness, dangerous risk taking, and safety knowledge. Journal of Safety Research, 34, 227–240.

White, D. D., & Hendee, J. C. (2000). Primal hypotheses: The relationship between naturalness, solitude, and the wilderness experience benefits of development of self, development of community, and spiritual development. In USDA Forest Proceedings RMRS-P-VCL-3, 2000 (pp. 223–227).

Yarnal, C. M., Chick, G., & Kerstetter, D. L. (2008). I did not have time to play growing up … so this is my play time. It’s the best thing that I have ever done for myself: What is play to older women? Leisure Sciences, 30, 235–252.

Zuckerman, M. (1969). Theoretical formulations. In J. Zubek (Ed.), Sensory deprivation: Fifteen years of research. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Zuckerman, M. (1971). Dimensions of sensation thinking. Journal of Counselling and Clinical Psychology, 36, 45–52.

Zuckerman, M. (2007). The sensation seeking scale V (SSS-V): Still reliable and valid. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1303–1305.

Zuckerman, M., & Aluja, A. (2014). Measures of sensation seeking. In G. J. Boyle, Sakloofske, & G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological constructs. London: Elsevier.

Zuzanek, J., & Zuzanek, T. (2014). Of happiness and of despair, is there a measure? Time use and subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1–18.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Joseph Sirgy, M., Uysal, M., Kruger, S. (2018). A Benefits Theory of Leisure Well-Being. In: Rodriguez de la Vega, L., Toscano, W. (eds) Handbook of Leisure, Physical Activity, Sports, Recreation and Quality of Life. International Handbooks of Quality-of-Life. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75529-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75529-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-75528-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-75529-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)