Abstract

Leisure is a key life domain and a core ingredient for overall well-being. Yet, within positive psychology, its definition and the psychological pathways by which it evokes happiness are elusive (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2008). In this paper, we seek to address these issues by delineating leisure and presenting a conceptual framework linking leisure to subjective well-being (SWB). Leisure is defined as a multidimensional construct, encompassing both structural and subjective aspects. Respectively, it is the amount of activity/time spent outside of obligated work time and/or perceived engagement in leisure as subjectively defined. To explain the effects of leisure on SWB, a quantitative summary of theories from 363 research articles linking leisure and SWB was conducted. Based on our findings, we propose five core psychological mechanisms that leisure potentially triggers to promote leisure SWB: detachment-recovery, autonomy, mastery, meaning, and affiliation (DRAMMA). These psychological mechanisms promote leisure SWB which leads to enhanced global SWB through a bottom-up theory of SWB. We discuss how future research can use this conceptual model for understanding the interplay between leisure and SWB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

He enjoys true leisure who has time to improve his soul’s estate. - Henry David Thoreau

Poets, philosophers, and pilgrims have promoted the role of leisure in well-being. Well before Henry David Thoreau commented on leisure’s relation to well-being, Aristotle discussed the importance of leisure, arguing that leisure is more important than work because leisure provides pleasure and happiness in life (Aristotle 1998, Politics, VIII, III), which is “something final and self-sufficient, and is the end of action” (Aristotle 1980, Nichomachean Ethics, I, VII). This belief that SWB can be precipitated by leisure continues to our current day and may explain the persistent growth in tourism—widely considered to be a leisure activity—despite the waning economy. In 2010, international tourist receipts reached $919 billion, marking a 4.7 % increase in real terms from the previous year (UNWTO 2011). During the first 6 months of 2012, 22 million more international arrivals were reported, marking a 5 % increase from the same time period in 2011 (UNWTO 2012). Thus, despite growing concerns over the struggling global economy, it is evident that people greatly value leisure and most likely believe it will promote their well-being. In fact, boosts in happiness levels prior to vacations (e.g., Nawijn et al. 2010) likely indicate that people anticipate and expect holiday trips to increase their well-being.

Recently, popular notions that leisure enhances subjective well-being (SWB) have gained increasing scientific support. Many studies have shown that SWB positively correlates with different aspects of leisure, such as visiting family and friends, playing sports or games, watching television, listening to the radio (e.g., Menec and Chipperfield 1997; Yarnal et al. 2008), taking tourist trips (Mitas 2010), making art (Reynolds and Lim 2007), and using the internet (Koopman-Boyden and Reid 2009). This positive relation has persisted across various subpopulations, including adolescents (Staempfli 2007), retirees (Kuo et al. 2007), and even schizophrenics (Mausbach et al. 2007). In fact, in a study of USSR college students, leisure and recreation satisfaction was shown to be the strongest predictor of overall SWB, measured through an event memory task as well as traditional survey methods (Balatsky and Diener 1993). Satisfaction with recreation correlated with three measures of SWB—Delighted-Terrible scale (Andrews and Withey 1976), Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985), and a global domain—higher than any other domain, such as satisfaction with housing, education, paid employment, friendship, or even family relationships. This high correlation with SWB has garnered support in previous studies as well (Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell et al. 1976; Headey et al. 1991).

Despite the positive relation, less is known about when and how leisure enhances overall SWB (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2008). In part, researchers have defined leisure in various ways such as time not occupied by paid or unpaid work or personal chores and obligations (Roberts 1999; Sonnentag 2001), preferred activities pursued during free time for their own sake, fun, entertainment, or self-improvement (Argyle 1996), free time which allows the mind to contemplate physical and spiritual realities (Pieper 1952), a state of being characterized by freedom and intrinsic motivation (Iso-Ahola 1997; Passmore and French 2001), and as a multidimensional construct including both activities and a subjective state of mind (Edginton et al. 2002; Haworth and Veal 2004). Moreover, less work has clearly demarcated the differences between leisure and constructs such as leisure satisfaction or recreational satisfaction, which may be construed as part of SWB.

Further, different conceptual mechanisms for how leisure promotes SWB have been proposed. Some scholars emphasize the experience of flow during leisure which in turn relates to higher SWB (Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre 1989). Others underscore the experience of disengagement during non-work time as an antecedent of well-being (e.g., Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Sonnentag and Zijlstra 2006). And others draw on self-determination theory (Ryan and Deci 2000) to show how leisure experiences generate SWB (e.g., Kleiber et al. 2011, pg. 167). There is an assemblage of approaches but no overarching conceptual framework that summarizes the key pathways between leisure and SWB.

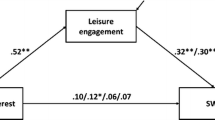

In this paper, we seek to address these conceptual gaps by establishing a psychological model that links leisure to SWB in general through a bottom-up approach (see Fig. 1). In this model, we propose an operational definition of leisure that enables researchers to quantify leisure in relation to leisure satisfaction and global SWB. Also, we conducted a literature review of leisure and SWB to identify and summarize the key theoretical linkages. Based on the review, we propose that both structural leisure (e.g., leisure-type activities and time spent outside obligated work time) and subjective leisure (e.g., perceived leisure frequency and perceived participation in leisure) relates to SWB via psychological mechanisms (i.e., detachment-recovery, autonomy, mastery, meaning, affiliation) by promoting the domain of leisure as one of many domains affecting global SWB.

The goal of this paper is to integrate the psychological mechanisms from various theories relating leisure and aspects of SWB via a quantitative summary of the literature. In so doing, we establish a conceptual model in which key psychological mechanisms promote specific aspects of the leisure domain SWB. Although there are many psychological theories on SWB, not all aspects are equally applicable to the domain of leisure. For instance, Maslow’s theory of needs posits that the fulfillment of basic needs such as housing and food is important for happiness. However, this may not be a relevant mechanism underlying leisure and SWB. Therefore our paper aims to uncover key mechanisms in the literature linking leisure to SWB. Our contribution is the identification of key mechanisms and an integrative summary of how leisure promotes SWB. In the process, we also seek to provide conceptual clarity on the components of leisure and SWB, and pinpoint novel areas that require more research.

2 Conceptualization of SWB

According to Diener’s tripartite model of SWB (Diener 1984), SWB consists of high life satisfaction, high positive feelings, and low negative feelings. Life satisfaction is an overall judgment of life; positive and negative feelings capture positive and negative affective experiences, respectively. Each component is distinct but related with good psychometric evidence establishing this model (Arthaud-Day et al. 2005; Lucas et al. 1996). Although there are different ways of configuring these components in relation to SWB (see Busseri and Sadava 2011), it is clear that each component is necessary for describing the domain space of SWB. Unfortunately, how these different aspects are related to leisure has not received conceptual attention. In our review, we use the term SWB to encompass these different aspects. In our analysis, we propose that the fulfillment of certain psychological experiences will enhance SWB in leisure and as a whole, without differentiating the components of SWB. After delineating the various psychological pathways linking leisure to SWB, we posit how leisure may differentially affect satisfaction, positive feelings, and negative feelings in leisure SWB and global SWB.

3 Bottom-Up Theory of SWB: Leisure SWB and Global SWB

In our theoretical model (See Fig. 1), we utilize a bottom-up perspective which argues that global SWB is based on a weighting of key life domains such as leisure, work, and health. Therefore engaging in leisure could potentially promote the various dimensions of SWB in the leisure domain, which subsequently promotes global SWB (for review of bottom-up and top-down theories, see Diener 1984; Diener and Ryan 2009).

Campbell et al. (1976) originally proposed a satisfaction judgment model of global life evaluations, a completely bottom-up approach that argues that global evaluations can be entirely and accurately summed from individual domains. While empirical studies have not validated this model completely, there has been substantial evidence in support of a partial bottom-up approach. In strong support of a bottom-up approach of SWB, specific domains affect SWB most strongly when they are congruent with individuals’ values (Oishi et al. 1999). For instance, those who place high value in power domains find greater satisfaction in buying expensive clothes than those who do not value power domains. Likewise, those who value and experience high levels of satisfaction in leisure experience greater levels of life satisfaction. Similarly, when a specific domain is accessible to an individual, domain satisfaction correlates more strongly with global life satisfaction (Strack et al. 1988). Along these lines, life satisfaction judgments are made from salient, relevant, and accessible sources of information (Schimmack et al. 2002). Some of these sources produce temporal changes in life satisfaction (e.g., spring break) while others produce more stable changes (e.g., academic success). Further, when participants are asked to think about a particular domain, their domain satisfaction influences life satisfaction. This evidence supports a bottom-up approach to SWB.

The bottom-up perspective has also recently received renewed interest because of Kahneman’s (1999) proposal of “objective happiness,” which is defined as the aggregate of individual moments of happiness. Individuals evaluate each moment as good or bad affective states and these moments can be assigned a numerical value; summing affective states across different situations can allow researchers to accurately determine the overall happiness of individuals (e.g., Dockray et al. 2010; Kahneman et al. 2004; Killingsworth and Gilbert 2010). This approach weights overall happiness based on time durations, which is different from a subjective weighting approach assumed when individuals make responses to indicators of global SWB. However, the logic is consistent with a bottom-up perspective to global SWB. In Kahneman et al.’s (2004) research, it was shown that happiness during leisure was substantially higher than during work or commuting. This perspective affirms that leisure SWB can significantly raise overall happiness.

4 Leisure: A Psychological Perspective

We seek a psychological definition of a leisure construct that encompasses the broad brushstrokes of current perspectives (Iso-Ahola 1979; Kleiber et al. 2011; Neulinger 1974, 1981) and enables us to quantify the extent individuals experience leisure in relation to SWB. We propose that leisure is the amount of activities/time spent outside obligated work time and/or engagement in leisure as subjectively defined. This perspective on leisure integrates two schools of thought on leisure: structural and subjective. In the following, we describe both structural and subjective leisure as ideal types, recognizing that in practice, researchers may often combine both aspects of leisure.

4.1 Structural Leisure

The structural aspects of leisure are frequently considered by psychologists and sociologists to be one approach to understanding leisure (e.g., Kelly and Godbey 1992; Kleiber et al. 2011). We use the term structure to emphasize how leisure is structured by time or activity. Based on this definition, leisure may be indexed by (a) the amount of time spent outside of work, such as the number of evenings or hours set aside to spend with friends or family. By extension, leisure can also be indexed by the frequency of leisure activities (e.g., Brajša-Žganec et al. 2011; Lloyd and Auld 2002). Specifically, frequency is anchored in the number of times individuals engage in a specific leisure-type activity; or (b) the number of activities typically viewed as leisure (e.g., watching a movie). For example, the amount of leisure diversity is defined as the number of different leisure activities individuals endorse. In some cases, researchers have referred to this as objective leisure (e.g., Kleiber et al. 2011), but we prefer to use the term “structural” because the term “objective” has a strong connotation that this form of leisure is not self-reported, which in practice is often the case. The sense in which structural leisure is objective, however, lies in whether the time or activity is anchored in a specific manner. For instance, researchers who measure non-work time and assume this to be leisure would be using a structural approach to leisure. However, researchers who measure amount of leisure time, without specifying what constitutes leisure, would use a subjective approach to leisure.

4.2 Subjective Leisure

Although structural aspects of leisure are informative, they are incomplete from a psychological perspective. This is because a structural definition imposes an unwritten assumption that the amounts of time spent outside of work or specific activities constitute leisure for individuals. Nevertheless, this may not necessarily be the case. For instance, some individuals may engage in and consider exercise as leisure whereas others view it as a chore. Therefore, it is important to measure the subjective sense of leisure involvement. A defining quality of subjective leisure is that individuals perceive themselves to be engaging in leisure; and leisure broadly covers activities or time that are construed as leisure by individuals. Based on this definition, a key difference between structural and subjective leisure is whether leisure is externally defined or internally defined.

Within leisure sciences, this view of leisure has often been conceptualized and measured as participation (e.g., Tinsley and Eldredge 1995) in leisure. It is also possible to measure it as frequency (e.g., Russell 1987) in a global sense, which is not tied to a particular activity or time. For example, one may ask participants the frequency of leisure activities in a week. In this manner, participants decide subjectively what leisure looks like for them, and make ratings on the amount of it. These measures may often use rating scales for participation and frequency (See Fig. 1).

This conceptualization of subjective leisure is distinct from leisure SWB which focuses on the evaluations and affective reactions to leisure measured by leisure satisfaction or affective experiences in leisure (e.g., positive and negative feelings experienced during leisure). Subjective leisure emphasizes perceived amount whereas leisure SWB emphasizes perceived enjoyment. Further, subjective leisure is also different from the subjective or experiential definition of leisure; that is, how an activity is construed as leisure (we elaborate on why in the following section) (see Kelly and Godbey 1992; Kleiber et al. 2011).

4.3 Interface Between Structural and Subjective Aspects

Our dual definition of leisure is proposed as ideal types for conceptual clarity. However, in the measurement of leisure, these two aspects may be combined. For example, individuals may be presented with a checklist of activities in which they are asked for whether they engage in an activity (“Not applicable/Do not enjoy”) and frequency of engagement (“Never” to “Every Day”) within the same response scale (e.g., Pressman et al. 2009). Therefore in our theoretical model (see Fig. 1), structural and subjective leisure fall under a broader category of leisure. Another related issue worth mentioning is that although the proposed definitions of leisure are consistent with past theory (e.g., Kleiber et al. 2011), these definitions may also be interpreted as leisure engagement, or the degree to which individuals participate in leisure—structural and subjective. In which case, structural and subjective leisure may be viewed as two approaches for measuring leisure engagement.

It is important to note that leisure researchers frequently employ an experiential definition of leisure (Chick 1998; de Grazia 1962; Kelly 1982), in which they attempt to define leisure by “free choice”, or a sense that an activity is “freely chosen” (e.g., Dattilo and Kleiber 1993; Mannell and Iso-Ahola 1987). The emphasis focuses on when activities are properly construed as “leisure.” There are several reasons why we do not include this definition for our present purposes. First, one issue with the experiential definition is that it carries the assumption that leisure has to be freely chosen. However, the philosophical nature of free choice, and the culture and social environmental constraints on leisure choices (Stebbins 2005) make it difficult to ascertain when an activity actually conforms to this cardinal criterion. Second, even if experiential leisure is defined solely on the basis of a subjective sense that it is freely chosen (i.e., “I freely choose this activity [Yes/No]”), it confounds the construct of autonomy (i.e., free choice) with the construct of leisure. For the purposes of our theoretical model, we are motivated to disentangle these two aspects so as to address whether leisure promotes SWB via a psychological mechanism such as autonomy. Third, in our psychological model of leisure and SWB, we are less concerned with whether a reported activity complies with a theoretic definition of leisure. Instead, we are interested in whether individuals are engaging in activities commonly viewed as leisure (structural leisure), or whether participants sense that they are getting enough leisure as defined on their own terms (subjective leisure). Both aspects measure the degree to which individuals engage in leisure.

The advantage of excluding the experiential definition of leisure is that it opens up the possibility that different individuals, demographic groups, and cultures may have differing notions of what leisure is, and what types of activities constitute leisure. By implication, it is possible that groups of individuals who engage in specific types of leisure activity but not experience autonomy (i.e., free choice) may be less happy. This enables us to address when leisure—as defined by individuals or societies—has salutary effects on SWB, and when it does not. For research purposes, we are less encumbered by whether an activity fulfills the restrictive requirement to be defined as leisure, in order to be included in our leisure construct space. For example, we can address whether leisure in the form of habitual to obsessive TV watching enhances SWB, and not only whether leisure in the form of “freely chosen” TV watching enhances SWB.

5 Leisure and Psychological Mechanisms

In our conceptual model, we propose that both structural and subjective aspects of leisure are related to leisure SWB via similar psychological mechanisms. In the following, we present how these psychological pathways are derived from the literature. Our proposed theoretical model suggests that certain psychological mechanisms are activated in leisure, which can directly promote the different aspects of SWB in leisure. The idea that psychological mechanisms greatly influence the quality of leisure is supported by Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre’s (1989) finding that flow is a greater predictor of the enjoyment of the activity than the form or type of the activity. The extent to which individuals experienced mastery and autonomy in their activities, thus producing a sense of flow, influenced the quality of the activity more than the subjectively assigned label of work or leisure. Thus, the underlying psychological mechanisms in leisure are critically important in understanding the nature of SWB in leisure.

Our goal was to develop a psychological model that parsimoniously covers the key mechanisms relating leisure and SWB from various theoretical perspectives. To do so, we conducted a quantitative summary of the existing theories based on a literature search. A keyword search on PsycINFO using “leisure or recreation” and “well-being, life satisfaction, quality of life, emotion, or happiness” recovered 3,620 articles. Out of these articles, 363 peer-reviewed articles and book chapters were identified as relevant to the topic as they sought to examine the relation between leisure and SWB. Out of this subset, 248 articles did not cite or reference any specific frameworks; and 15 theories were cited or referenced by just one article. Because we sought parsimony, we focused only on theories that were cited or referenced by at least two articles in the literature. The articles were examined for the theories proposed and the underlying psychological processes invoked by the theory.

An initial taxonomy of psychological processes—affiliation, mastery, meaning, and autonomy—linking leisure and SWB was based on prominent theories within SWB. Theories of SWB by Maslow (1954), Ryff and Keyes (1995), Ryan and Deci (2000), and Csikszentmihalyi (1990) emphasize the fulfillment of different psychological needs such as mastery, autonomy, affiliation, and meaning required to enhance SWB. Specifically, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs argues that affiliation (termed belongingness and love at the middle level) is necessary at various stages for an individual’s well-being. Ryff and Keyes’ (1995) six dimensions of psychological well-being support the experiences of autonomy, mastery, meaning, and affiliation. Ryan and Deci (2000) argue that the satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, and competence promotes psychological well-being; relatedness can be mapped on to affiliation, while competence can be construed as mastery.

Using this set of psychological mechanisms, we proceeded to code for psychological mechanisms implied by the theories. We found that our list of four mechanisms was comprehensive but did not account for detachment-recovery. In work psychology, leisure activities have been studied using the perspectives of disengagement from work (e.g., Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Sonnentag and Zijlstra 2006), conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989), and effort recovery (Meijman and Mulder 1998). Therefore, the primary function of leisure is to produce psychological detachment from work, which is a precursor to the restoration of psychological and physical resources required for continued functioning and well-being (Etzion et al. 1998). Based on this, we added detachment-recovery as another key psychological mechanism to our list.

Table 1 reveals the results of our initial analysis. We rank the number of times various theories have been mentioned and present a short summary of each theory. For each theory, we identified and proposed key psychological mechanisms (explicit or implicit in the theory) that link leisure to SWB. The theories, frameworks, and models most cited in the literature establish that these psychological mechanisms enhance SWB in leisure.

After this initial step of identifying five psychological mechanisms from the 363 peer-reviewed articles, we selected a random subset of 100 articles from the larger subset of 248 articles that did not reference any specific theory or framework. Since the 248 articles were listed chronologically by date of publication, we selected two articles to code and then skipped the next three. We continued this process to create a chronologically representative sample. These 100 articles were tested to determine if the five psychological mechanisms proposed could be interpreted as potential mediating factors relating leisure to SWB. For example, while Heo et al. (2011) do not reference any specific theory or model, social relationships, detachment, and meaning are clearly measured as mediating factors between leisure satisfaction and internet usage in older adults. In this subset of 100 articles, 72 articles include at least one of our psychological mechanisms as a potential mediating factor. Therefore, the psychological mechanisms selected accurately and comprehensively reflect the majority of research on leisure and SWB. Table 2 shows the results from this tally. In the following, we elaborate on the theoretical underpinnings for each proposed mechanism and summarize empirical evidence relating leisure and SWB.

5.1 Detachment-Recovery

Theories from the literature that support detachment and recovery from work as a mechanism linking leisure to SWB include the conservation of resources theory (11 references) (Hobfoll 1989, 1998), the effort-recovery model (8 references) (Meijman and Mulder 1998), the attention-restoration theory (2 references) (Kaplan 1995), and compensation theory (2 references) (Chick and Hood 1996). These theories refer to the effect of demands and resources utilized in leisure on well-being. Specifically, the effort-recovery model states that leisure activities that draw on the same resources used during work will hinder the recovery process. Similarly, according to the conservation of resources model, individuals can build up resources during leisure time activities to overcome stress at work, thereby improving well-being. Both of these models have garnered empirical support (Fritz and Sonnentag 2005; Korpela and Kinnunen 2010; Sonnentag 2001; Sonnentag and Niessen 2008). The attention-restoration theory (Kaplan 1995) argues that time spent in nature facilitates cognitive recovery and negates the negative effects of stress. According to the compensation theory (Chick and Hood 1996), individuals tend to engage in leisure activities that draw on resources not used in work, which satisfies a larger range of needs and improves SWB. These specific theories and frameworks explain in nuanced ways how the process of detachment from work can mediate the relationship to SWB.

Specific studies that refer to these theories offer empirical support and describe in detail how detachment and recovery lead to SWB. Since work is effortful and strains one’s physiological and psychological resources, working continuously can produce negative SWB (e.g., burnout; Schaufeli et al. 2008). Under these conditions, time away from work is essential for recovery (Etzion et al. 1998; Meijman and Mulder 1998), which has been defined as a return to a homeostasis set point or to a mental baseline (Vittersø 2011). Nevertheless, not all time away from work leads to recovery, as an individual may not be psychologically detached (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007). For instance, one may be ruminating about work albeit trying to relax (cf. Cropley and Purvis 2003). To counter this process of rumination during nonwork time, individuals can cognitively switch off by engaging in distraction techniques. According to the self-regulation model of ruminative thought, distraction techniques include cognitive strategies such as attention switching and thought stopping as well as behavioral strategies such as engaging in new leisure activities requiring cognitive attention (Martin and Tesser 1996). Distraction from work has also been shown to improve sleep onset latency (Ellis and Cropley 2002), which would further lead to recovery. Therefore, nonwork contexts produce recovery when it helps individuals disengage from work-related matters.

Following this line of reasoning, leisure indirectly promotes SWB via detachment from work. Research has shown that quality leisure experiences leads to lower need for recovery, which in turn relates to higher SWB, specifically experience of fatigue (Sonnentag and Zijlstra 2006). Also, the extent individuals enjoy their leisure can be a proxy for detachment. Indeed, post-vacation life satisfaction was significantly higher than pre-vacation life satisfaction, particularly for those who enjoyed their vacations (Lounsbury and Hoopes 1986).

More generally, leisure not only produces detachment from work, but it can help individuals detach from life pressures and so produce more positive cognitions and emotions through recovery. Detachment and recovery can occur through rest, enabling recuperation from high levels of exhaustion from work, and may be characterized by sleeping or lying on the beach. Detachment and recovery can also occur through arousal-seeking behavior which provides respite from under-arousal or boredom at work through activities such as skydiving, skiing, or traveling to exotic locations. The types of leisure activities that produce detachment and recovery are not restricted to low arousal recovery activities (e.g., watching TV, reading a newspaper), but may include more physically intense forms of leisure (e.g., mountain biking, running) (Rook and Zijlstra 2006). In part, it may be because differences in job characteristics (e.g., level of job demands) are better matched with different types of leisure activities (cf. Chick and Hood 1996; Cropley and Purvis 2003; Sonnentag and Zijlstra 2006). For example, individuals who have demanding jobs may find low arousal recovery activities more restorative than high arousal activities.

5.2 Autonomy

In leisure studies, autonomy is usually viewed as a necessary requisite of leisure (e.g., Leisure and well-being model, compensation theory). Several important theories found in the literature include autonomy as a necessary mediating link to SWB in leisure. In particular, self-determination theory (SDT) (24 references) (Ryan 1995; Ryan and Deci 2001) states that autonomy is one of the three basic needs required of overall well-being. The high tally of SDT references in leisure research attests to the importance of autonomy in leisure. Aside from SDT, continuity theory (9 references) (Atchley 1976), innovation theory (2 references) (Nimrod 2008), compensation theory (2 references) (Chick and Hood 1996), and the leisure and well-being model (2 references) (Carruthers and Hood 2007) argue that autonomy is an essential mechanism promoting SWB in leisure. Continuity theory holds that individuals tend to participate in the same activities after a major change in life, allowing one to cope with change and enhance well-being (Atchley 1976, 1989), whereas innovation theory states that well-being is increased through engagement in new leisure activities after retirement (Nimrod 2008). While these theories may appear to be in conflict with each other, they actually both support a notion of autonomy, as continuity theory suggests that the participation in the same leisure activities actually restores perceptions of control and freedom which ultimately lead to SWB (Hutchinson et al. 2003). On the other hand, the link between innovation theory and autonomy is more easily apparent as the engagement in new leisure activities requires independence and self-direction. Compensation theory (Chick and Hood 1996) implies that autonomy is required of individuals as they choose leisure activities that engage in resources not used during work. Finally, the leisure and well-being model (Carruthers and Hood 2007) simply defines autonomy as a requisite of leisure, which when satisfied, leads to greater SWB. According to these theories, autonomy is an essential mediator between leisure activities and well-being.

In the context of leisure, researchers use terms such as intrinsic leisure motivation and autonomous motivation in leisure to more specifically describe autonomy’s relation to SWB. Intrinsic motivations describe activities that follow one’s inner interests, performed spontaneously and naturally (Deci 1975). Those who report higher levels of intrinsic motivation experience greater levels of life enjoyment and psychological well-being (Graef et al. 1983). More specifically defined, intrinsic leisure motivation (ILM) correlates positively with self-efficacy (r = .18) and predicts greater satisfaction with life (r = .19) and lower negative feelings (r = .29) (Byrd, Hageman, and Belle Isle 2007). ILM also correlates with happiness (r = .55), is associated with a high level of flow (Haworth and Hill 1992), and may act as an escape from distresses in life (Byrd et al. 2007). As a form of ILM, intrinsic religious motivation in leisure promotes SWB by reducing stress (Maltby and Day 2003, 2004) and by improving a sense of self-actualization, self-acceptance, and a freedom from guilt and worry (James and Wells 2003).

Autonomous motivation may be seen as another way of describing autonomy. When individuals engage in activities willingly, out of their own volition and choice, they are autonomously motivated. Research has found that well-being correlates more positively to autonomous motivation in leisure (r = .34) than autonomous motivation in work (r = .27) (Derous and Ryan 2008). Autonomous motivation is also measured using the term autonomy-supportive contexts, in which well-being in women is enhanced in leisure-time physical activity (Chatzisarantis and Hagger 2009; Lloyd and Little 2010) when they are provided with a sense that they “can do their own thing” (Wearing 1998).

5.3 Mastery

Mastery experiences encompass activities that challenge individuals and provide learning opportunities. Mastery is a distinct mechanism from autonomy in that mastery focuses on the efforts put into honing one’s skills or achieving a new level of success in a leisure activity. Whereas autonomy refers to the perception of individuality, choice, and freedom in leisure, mastery describes the overcoming of challenges and betterment of skill in leisure activities.

The numerous references to flow (44 references) (Csikszentmihalyi 1990) and serious leisure (14 references) (Stebbins 1992, 1997) from our literature support the notion that mastery is an essential mediating link to SWB. Csikszentmihalyi’s (1990) concept of flow taps into the mastery experience, as individuals enter a state of flow by being engaged in an activity that produces sufficient challenge. The appropriate balance of challenge and skill enables an individual to enter a state of total absorption and concentration, ultimately leading to optimal experience and well-being through the mechanism of mastery. This balance of challenge and skill required of flow matches mastery in its relation to SWB in leisure time activities. As yet another prominent model of leisure, serious leisure also supports the importance of mastery. This model of leisure posits that serious involvement of effort, skill, and commitment to a leisure activity leads to greater life satisfaction (Stebbins 1992, 1997). Stebbins argues that serious leisure promotes self-actualization, self-enrichment, regeneration or renewal of the self, and a sense of accomplishment, which are closely tied to mastery experiences.

Not only do the references to these theories support mastery as a mechanism, but empirical research also provides evidence on mastery’s behalf. It has been found that individuals who enter a state of flow during leisure activities report higher levels of positive feelings (Pinquart and Silbereisen 2010). In line with this, a controlled and rigid engagement in leisure activities, termed obsessive passion, does not lead to higher levels of SWB and is unrelated to flow (Stenseng et al. 2011). Although flow experiences occur more frequently in work than leisure (Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre 1989), mastery in leisure activities nevertheless promotes SWB by providing individuals a sense of accomplishment and flow experiences. Examples of these activities could include intellectually stimulating tasks, such as playing chess or learning a foreign language, or physical challenges, such as training for a marathon (Mojza et al. 2010). In addition, individuals who engage in serious leisure show more successful aging (Brown et al. 2008). Learning as a form of mastery has also been found to be related to SWB. Educational classes taken during free time as a form of leisure stimulate cognitive processes, which in turn promote positive feelings (Simone and Cesena 2010).

Overall, research has demonstrated that leisure activities that invoke mastery experiences likely lead to higher SWB. A positive correlation of .22 has been found between mastery experiences in leisure time and life satisfaction (Sonnentag and Fritz 2007). Mastery experiences during vacation also predict lower levels of exhaustion after returning to work (Fritz and Sonnentag 2006).

5.4 Meaning

Meaningful leisure activities, also referred to as meaning-making through leisure, are a means by which individuals gain something important or valuable in life (Iwasaki 2008). Examples such as running (Major 2001), quilting (King 2001), aboriginal dancing (Iwasaki et al. 2006), volunteering, and storytelling (Wearing 1998) add meaning and purpose to one’s life. Meaningful leisure activities reduce negative emotions while promoting positive emotions and life satisfaction. More specifically, Baumeister and Vohs (2002) argue that meaning-making remedies the bad and enhances the good.

Meaning is a vital mechanism in leisure to SWB due to the support and references to serious leisure (14 references) (Stebbins 1992), flow (44 references) (Csikszentmihalyi 1990), activity theory (27 references) (Havighurst 1961), the selection, optimization, and compensation theory (SOC) (7 references) (Baltes and Baltes 1990), and socioemotional selectivity theory (4 references) (Carstensen 1992) found in the literature search. Meaning, like mastery, is also promoted by serious leisure’s model, as meaningful engagement and strong commitment are requisites of serious leisure. Activity theory (27 references) also supports meaning as a mechanism mediating SWB in leisure, although not quite as directly as affiliation. According to a traditional perspective of activity theory, the frequency of participation in leisure and the level of intimacy predict SWB (Atchley 1977; Lemon et al. 1972; Rodríguez et al. 2008; Sener et al. 2007), thus supporting affiliation. However, according to a nuanced perspective of activity theory, engagement with life is essential for healthy aging (Rowe and Kahn 1997). Engagement with life involves not only maintaining close relationships but also remaining involved in productive activities that are meaningful and purposeful, thus endorsing meaning as a vital link to SWB.

SOC theory argues that as individuals age, they must choose a select number of meaningful activities in which to engage. Since older people can no longer participate in the vast array of activities earlier in life, they must optimize leisure activities to find the most meaning, which subsequently leads to SWB. Similarly, socioemotional selectivity theory states that as people become aware of the diminishing amount of time left to live, they seek out emotionally meaningful engagements and relationships. Individuals tend to act in this manner to improve their general well-being, which implies that the meaningful activities they seek at least partially account for the improved SWB. These theories do not exclusively apply to leisure activities, but their implications in leisure activities offer compelling evidence that meaning in leisure promotes SWB.

Elsewhere in the literature on leisure and SWB, it has been shown that meaning obtained from leisure appears to exert positive effects on well-being, cultural differences notwithstanding (Iwasaki 2007). For example, in cultures worldwide, meaningful leisure activities promote tranquility and peace of mind (Gong 1998; Yang 1998), affirm self-worth and pride (Wearing 1998), facilitate growth and development (Mantero 2000), help one cope in response to difficult life circumstances (Waters and Moore 2002), and enable physical and social engagement (Silverstein and Parker 2002). More generally, meaningful leisure activities foster a global sense of meaning of the individuals (Iwasaki et al. 2006). In these meaningful leisure activities, people find positive emotions, which are the “markers of optimal well-being” (Fredrickson 2002, p. 120). Moreover, meaning in life has even been regarded as an important component of well-being in itself (Ryff 1989).

Further, religious practices such as prayer or meditation serve as avenues for meaningful leisure activities. Meditation promotes positive emotions, which in turn predict an increase in life satisfaction and a decrease in depressive symptoms (Fredrickson et al. 2008). Indeed, a representative world poll across 153 nations revealed that meaning was an important mediator between religious engagement and SWB (Diener et al. 2011).

5.5 Affiliation

Leisure activities can be solitary or social. We propose that social activities meet our affiliative needs which produce higher SWB. The prominent theories discovered in the literature that endorse affiliation as a mechanism promoting SWB include the following: activity theory (27 references) (Havighurst 1961), disengagement theory (14 references) (Cumming and Henry 1961), Maslow’s (1954) hierarchy of needs (12 references), SOC theory (7 references) (Baltes and Baltes 1990), socioemotional selectivity theory (4 references) (Carstensen 1992), the leisure and well-being model (2 references) (Carruthers and Hood 2007), and need theory (2 references) (Diener and Lucas 2000). Affiliation, like meaning, is endorsed as a link to SWB by activity theory since engagement with others as one ages is necessary for SWB. In contrast to activity theory, disengagement theory (7 references) argues that as individuals get older, they tend to withdraw from social relationships, focusing instead on personal growth to improve SWB. Although these theories disagree on how affiliation promotes well-being, the frequency of citations of both theories supports the experience of affiliation as a mediator to SWB.

Maslow (1954) argues that the third rung of his hierarchy of needs termed love and belongingness is an essential need of humans after physiological and safety needs are met. The sense of belonging, a connection and affiliation to others, can be applied to leisure time activities. SOC theory is founded on the assumption that affiliation is important as it states that individuals must be selective in the relationships they choose as they age. Likewise, socioemotional theory argues that adults prefer emotionally rewarding relationships as they age. The leisure and well-being model (Carruthers and Hood 2007) states that interpersonal capacities that support social connectedness lead to satisfaction. Need theory (Diener and Lucas 2000) proposes that the satisfaction of basic needs such as social support and contact are prerequisites for SWB. The connecting link in each of these theories supporting SWB is social affiliation. The general number of references suggests that affiliation is likely a significant factor in promoting SWB.

Specific studies on leisure explain how affiliation accomplishes this task. Social leisure activities build social relationships, encourage positive emotions and ultimately improve quality of life (Brajša-Žganec et al. 2011; Rook 1987). On the other hand, social leisure activities may inhibit negative emotions as they have been shown to decrease loneliness (Caldwell and Smith 1988) and sadness (Boneham and Sixsmith 2006; Taylor et al. 2000) by creating a shared experience among participants (Waters and Moore 2002). Moreover, social leisure activities can foster social support (Coleman and Iso-Ahola 1993; Freysinger and Flannery 1992; Son et al. 2010) which can produce higher levels of happiness as supporters help regulate affect and thoughts through shared activities (Lakey and Orehek 2011).

Social affiliation may promote SWB indirectly because social activities form a basis for social support, which affords resources that help buffer against stressful life events (Antonucci and Akiyama 1991; Cohen and Wills 1985). A caveat is that there is limited evidence for the buffering hypothesis since social support has not been found to reduce the effects of work stress on life and job dissatisfaction (Ganster et al. 1986). Indeed, a recent comprehensive review on buffering effects for mental health shows inconsistent results (see Lakey and Cronin 2008).

The social-solitary dimension in leisure activities categorizes various leisure activities such as going to parties with friends or playing team sports as social while grouping other leisure activities such as watching television or reading a book as solitary or nonsocial (Lemon et al. 1972; Reitzes et al. 1995; Winefield et al. 1992). Social leisure activities have been positively correlated with life satisfaction (Kelly et al. 1987) and happiness as measured by the frequency of smiles (Reyes-Garcia et al. 2009). Trainor et al. (2010) found that activities with other people correlated positively with life satisfaction (r = .22, respectively). They also found a positive correlation between solitary activities and negative mood (r = .21) and a negative correlation between solitary activities and life satisfaction (r = −.09). Further, low social activity during the weekend predicted lower well-being after the weekend (Fritz and Sonnentag 2005). This strongly suggests that social affiliation is an important experience for leisure on subjective well-being.

Among the five psychological mechanisms, social affiliation has the most support from multiple theoretical perspectives. As seen in Table 2, affiliation was listed as a possible mediator between leisure and SWB more times than any other psychological mechanism in our subset of 100 articles. This suggests that social affiliation may be the strongest predictor, or perhaps the most consistent predictor of SWB, across various contexts. According to a sample of 222 undergraduates, the happiest 10 % spent more time socializing and had stronger social relationships than the others (Diener and Seligman 2002). Within leisure specifically, social contexts are vitally important in raising SWB as warmth from friendships has been discovered as a primary process linking leisure activities to SWB (Mitas 2010).

As a specific form of social affiliation in leisure, activities involving play can mediate affiliation’s relation to SWB. Play is involved in many leisure activities (Sutton-Smith 1997), but it has been categorized as a social form of leisure (Burghardt 2005) as it promotes social bonding in leisure activities such as bingo (Cousins and Witcher 2004) and Red Hat Society gatherings, an organization of older women with the purpose of being “silly and goofy” (Yarnal et al. 2008). Not only does play develop social relationships (Fagen 1981, p. 65), but it also raises self-esteem, boosts confidence in decision-making, and increases openness to new experiences (Yarnal et al. 2008).

While research shows that social affiliation promotes SWB, it must be noted that the people with whom one affiliates during leisure activities may influence the types of benefits experienced. Leisure time with friends increases immediate well-being, while leisure time with a spouse increases global well-being (Larson et al. 1986). Future research can further examine the various types of relationships engaged in social leisure activities.

6 Components of SWB

Each mechanism outlined above is argued to serve as a mediating link between various forms of leisure activities and SWB, which is comprised of three distinct yet related components. This review thus far has not differentiated the specific aspects of SWB that these mechanisms (i.e., detachment-recovery, autonomy, mastery, meaning, and affiliation [DRAMMA]) promote. This is mostly due to the fact that the literature on leisure and well-being frequently conceptualizes SWB as a single component, or measures only a specific facet, making it difficult to ascertain whether leisure promotes one aspect (e.g., life satisfaction) over another (e.g., positive emotions). In our view, where more positive psychological processes occur, we would expect greater SWB on the whole. However, it is possible that different psychological experiences can also promote more specific aspects of SWB although they tend to rise and fall together. For example, we speculate that the fulfillment of basic needs in leisure such as having time for rest and recovery will more likely enhance life satisfaction and diminish negative feelings. This may be because individuals evaluate living and working standards when rating life satisfaction. Having sufficient detachment and recovery during leisure would be a critical component of life satisfaction. Further, not receiving sufficient detachment and recovery likely triggers negative feelings, but receiving sufficient detachment and recovery may not necessarily lead to increased positive feelings. Indeed, a study by Tay and Diener (2011) using a representative world sample showed similar patterns whereby life satisfaction and lessened negative feelings were tied to the fulfillment of basic needs whereas positive feelings were tied to the fulfillment of higher order needs. Nevertheless, the researchers showed that needs have an additive effect, such that the fulfillment of psychological experiences were not substitutable and each contributed to all components of SWB.

The relationship between leisure and specific aspects of SWB is further complicated due to the two different manners in which leisure is defined: subjective and structural. We propose that subjective aspects of leisure may be tied more with life satisfaction because both tap on to an evaluative aspect, namely the degree to which one engages in leisure (e.g., participation or frequency). Structural aspects of leisure will likely promote SWB feelings. Kahneman et al.’s (2004) research using Day Reconstruction Method shows that positive feelings were high and negative feelings were low for activities such as socializing, eating, relaxing, and watching TV, whereas opposite trends were found for working and commuting. For both subjective and structural aspects of leisure, where more positive psychological processes occur (i.e., DRAMMA), we would expect greater SWB on the corresponding aspects of both leisure and life (i.e., structural leisure promotes positive feelings in leisure and life while diminishing negative feelings in leisure and life, whereas subjective leisure promotes leisure and life satisfaction).

These proposals need to be tempered with the fact that SWB components are often measured using different time frames. Life satisfaction is generally measured using a long time frame (e.g., 10 years) whereas positive feelings and negative feelings are measured using short time frames (e.g., 2 weeks or yesterday) (e.g., Luhmann et al. 2012). Therefore, when psychological experiences (or leisure components) and components of SWB are measured using the same time frames, we would likely see a stronger association due to a method effect. Future research can examine the extent to which structural and subjective leisure is linked to different components of SWB.

7 Implications

The theoretical model merges and incorporates a large number of theories, models, and frameworks to describe the psychological mechanisms that underpin SWB. These mechanisms encompass and succinctly summarize the multiplicity of theories found in the literature. This allows for a clearer conceptual understanding of how SWB relates to leisure. While individual theories relating to leisure and SWB have provided the necessary data to build this model, an individual theory or model may not encapsulate other elements for a broad account.

The theoretical model suggests that leisure activities or participation trigger certain psychological mechanisms. For example, the various leisure activities occurring outside of work time in many studies by Sonnentag and colleagues (e.g., Mojza et al. 2010; Sonnentag 2001; Sonnentag and Bayer 2005; Sonnentag and Fritz 2007; Zijlstra and Sonnentag 2006) trigger the detachment-relaxation mechanism, referred to in these studies by the effort-recovery model (Meijman and Mulder 1998) and the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989). Through the use of this model, we are able to look at the different psychological pathways by which leisure affects SWB.

The theoretical model explains why certain leisure activities promote SWB more than others. Leisure activities that fulfill multiple psychological needs, such as playing sports with friends (affiliation, mastery, and detachment-relaxation), would likely promote SWB more than leisure activities that fulfill only one mechanism, such as watching television (detachment-relaxation). Similarly, creating a photo notebook to capture memories as a leisure activity might promote life satisfaction, whereas writing a blog might also promote life satisfaction though through autonomy and mastery. Potential psychological mechanisms activated during tourist trips, such as affiliation, detachment-recovery, and autonomy, might explain the peak in mood levels that occur mid-way through tourist vacations (e.g., Mitas 2010; Nawijn 2010). Additionally, certain subpopulations might benefit more from certain leisure activities than others groups due to specific psychological needs. Older adults may experience greater SWB in leisure activities that fulfill the psychological experience of meaning. Similarly, working adults engaged in leisure activities that fulfill the need for detachment-relaxation may experience the greatest improvement in SWB; children may benefit the most from leisure activities involving social affiliation. Future research needs to examine the relation between age, leisure participation, and SWB (Brajša-Žganec et al. 2011).

While not specified in the theoretical model, we also propose that individual differences may moderate the relation between leisure and SWB. Certain individuals may react more positively to certain psychological experiences, resulting in greater increases in SWB. In a related area of research, the act of performing certain happiness-enhancing strategies, which fit well with one’s personality, goals, and interests, such as expressing gratitude or optimism, leads to greater levels of positive feelings following the happiness-enhancing activity (Sheldon and Lyubomirsky 2006). Similar results may be found in future research in leisure studies if the psychological experiences are studied in relation to the compatibility with one’s personality, goals, and interests. In fact, when self-congruent variables in respect to a specific culture are met in leisure, it can potentially raise one’s well-being above the set-point (Spiers and Walker 2009), similar to the way a happiness enhancing strategy can boost one’s happiness in the short term. Finding self-congruent variables in leisure has the added benefit that individuals are much more likely to naturally engage in leisure activities than happiness-enhancing strategies. Therefore, finding leisure activities that match individual’s preferred psychological mechanisms could raise subjective well-being long term.

8 Future Research

Most leisure research on SWB has been cross-sectional and correlational without measuring the specific causes of SWB during leisure time activities. Experimental studies aimed at isolating particular psychological mechanisms can delineate the strengths of various experiences. For example, although participation in team sports has been linked to high levels of life satisfaction in youth (Poulsen et al. 2006), explanations of this association has been speculative. Likewise, while leisure can have a great influence on the well-being of caregivers (Losada et al. 2010), the pathways supporting this has not been fully explicated. Experimental studies that separate psychological experiences such as mastery and affiliation will clarify how and why overall SWB increases after such leisure activities.

Longitudinal, developmental, and cross-cultural studies can either generalize the effects of certain experiences in leisure activities on SWB or indicate where cultures or various populations differ. This helps future research by specifying which psychological experiences are responsible for differences in cultures or subpopulations.

Furthermore, future research testing the theoretical model may provide new insight into the balance of work and leisure. Certain types of leisure might mesh well together with certain types of work. If one experiences high levels of autonomy at work, SWB may be increased to a greater extent if other experiences in leisure are utilized as research shows that the fulfillment of different needs are not substitutable in the promotion of SWB (Tay and Diener 2011). Alternatively, if certain psychological experiences are lacking at work, it might be beneficial to seek out leisure experiences that engage these very psychological experiences. The specific psychological mechanisms involved in work may also vary on the type of employment and it may behoove researchers to measure type of employment in relation to psychological mechanisms. Future research testing the interface of work and leisure will benefit by considering the psychological experiences outlined above.

Because our interest focuses on how leisure enhances SWB, we used a bottom-up perspective to underscore how leisure experiences cumulatively impacts general SWB via the DRAMMA psychological mechanisms. Although the proposed model is effective for our purposes, there are other causal processes between the constructs that were not emphasized. First, general SWB may affect the choice of leisure activity and perceived leisure engagement; that is, structural and subjective leisure, respectively. For example, individuals with higher levels of SWB tend to be more sociable (Diener and Tay 2012) and so may seek out social leisure activities, or may focus on positive aspects and perceive themselves as having more leisure than expected. Second, a top-down perspective states that general SWB affects the degree to which one is satisfied with leisure. Uplifts in mood and well-being accumulated over time may enhance global SWB that can color how individuals subsequently perceive the leisure domain.

9 Conclusion

Leisure is a key domain in life and can influence SWB in a positive manner. In certain studies, leisure activities and recreation satisfaction have even been shown to be greater predictors of life satisfaction and quality of life than sex, education, religiosity, marital status, age, health, employment status, and income (Riddick 1985; Russell 1990). However, increased amounts of leisure do not result in improved well-being across all demographics (e.g., the poor and elderly) (Cho et al. 2009). In fact, how and why leisure influences SWB has not been studied extensively in positive psychology (Diener and Biswas-Diener 2008).

We propose an integrative model based on past research that would be fruitful for future studies of the leisure-SWB association. We operationally define leisure in structural and subjective terms and propose five key psychological mechanisms based on theory: DRAMMA. These mechanisms promote SWB in leisure, which subsequently promote general SWB, integrated as part of a bottom-up theory of SWB. Nevertheless, more questions remain in the study of leisure and SWB. We hope that this framework can serve as a crucial platform for building future knowledge on leisure and SWB.

References

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum Press.

Antonucci, T. C., & Akiyama, H. (1991). Social relationships and aging well. Generations, 15, 39–44.

Argyle, M. (1996). The social psychology of leisure. New York: Penguin Books.

Aristotle. (1980). Nichomachean ethics. (W. D. Ross, Trans.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aristotle. (1998). Politics. (C. D. C. Reeve, Trans.). Indianapolis: Hackett.

Arthaud-Day, M. L., Rode, J. C., Mooney, C. H., & Near, J. P. (2005). The subjective well-being construct: A test of its convergent, discriminant, and factorial validity. Social Indicators Research, 74, 445–476.

Atchley, R. C. (1976). The sociology of retirement. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman.

Atchley, R. C. (1977). The social forces in later life. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Atchley, R. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29(2), 183–190.

Balatsky, G., & Diener, E. (1993). Subjective well-being among Russian students. Social Indicators Research, 28, 225–243.

Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2002). The pursuit of meaningfulness in life. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 608–618). New York: Oxford University Press.

Boneham, M. A., & Sixsmith, J. A. (2006). The voices of older women in a disadvantaged community: Issues of health and social capital. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 269–279.

Brajša-Žganec, A., Merkaš, M., & Šverko, I. (2011). Quality of life and leisure activities: How do leisure activities contribute to subjective well-being? Social Indicators Research, 102(1), 81–91.

Brown, C. A., McGuire, F. A., & Voelkl, J. (2008). The link between successful aging and serious leisure. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 66(1), 73–95.

Burghardt, G. (2005). The genesis of animal play: Testing the limits. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

Busseri, M. A., & Sadava, S. W. (2011). A review of the tripartite structure of subjective well-being: Implications for conceptualization, operationalization, analysis, and synthesis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 290–314.

Byrd, K. R., Hageman, A., & Belle Isle, D. (2007). Intrinsic motivation and subjective well-being: The unique contribution of intrinsic religious motivation. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 17, 141–156.

Caldwell, L. L., & Smith, E. A. (1988). Leisure: An overlooked component of health promotion. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 79 (March/April), S44–S48.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Carruthers, C., & Hood, C. (2007). Building a life of meaning through therapeutic recreation: The leisure and well-being model, part I. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 41(4), 276–297.

Carstensen, L. L. (1992). Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 7(3), 331–338.

Chatzisarantis, N., & Hagger, M. (2009). Effects of an intervention based on self-determination theory on self-reported leisure-time physical activity participation. Psychology and Health, 24(1), 29–48.

Chick, G. (1998). Leisure and culture: Issues for an anthropology of leisure. Leisure Sciences, 20(2), 111–133.

Chick, G., & Hood, R. D. (1996). Working and recreating with machines: Outdoor recreation choices among machine-tool workers in western Pennsylvania. Leisure Sciences, 18, 333–354.

Cho, H. K., Lee, K. Y., Lee, Y. S., Kim, O. S., Lee, S. M., Hong, D. S., et al. (2009). Time use and quality of life of the Korean rural poor. Social Indicators Research, 93(1), 223–227.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Coleman, D., & Iso-Ahola, S. (1993). Leisure and health: The role of social support and self determination. Journal of Leisure Research, 25, 111–128.

Cousins, S., & Witcher, C. (2004). Older women living in the bingo stereotype: ‘Well, so what? I play bingo. I’m not out drinkin’. I’m not out boozin. International Gambling Studies, 4, 127–146.

Cropley, M., & Purvis, L. J. M. (2003). Job strain and rumination about work issues during leisure time: A diary study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 12, 195–207.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperPerennial.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 815–822.

Cumming, E., & Henry, W. E. (1961). Growing old. New York: Basic Books.

Dattilo, J., & Kleiber, D. (1993). Psychological perspectives for therapeutic recreation research: The psychology of enjoyment. In M. J. Malkin & C. Z. Howe (Eds.), Research in therapeutic recreation: Concepts and methods (pp. 57–76). State College, PA: Venture Publishing.

de Grazia, S. (1962). Of time, work, and leisure. New York, NY: Anchor Books, Doubleday.

Deci, E. L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York: Plenum.

Derous, E., & Ryan, A. M. (2008). When earning is beneficial for learning: The relation of employment and leisure activities to academic outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(1), 118–131.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2008). Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2000). Explaining differences in societal levels of happiness: Relative standards need fulfilment, culture, and evaluation theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 41–78.

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South African Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

Diener, E., & Tay, L. (2012). A scientific review of the remarkable benefits of happiness for successful and healthy living. Report of the Well-Being Working Group, Royal Government of Bhutan: Report to the United Nations General Assembly, Well-Being and Happiness: A New Development Paradigm, UN, NY.

Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1278–1290.

Dockray, S., Grant, N., Stone, A. A., Kahneman, D., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2010). A comparison of affect ratings obtained with ecological momentary assessment and the Day Reconstruction Method. Social Indicators Research, 99, 269–283.

Edginton, C. R., Jordan, D. J., DeGraaf, D. G., & Edginton, S. R. (2002). Leisure and life satisfaction: Foundational perspectives. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Ellis, J., & Cropley, M. (2002). An examination of thought control strategies employed by acute and chronic insomniacs. Sleep Medicine, 3, 393–400.

Etzion, D., Eden, D., & Lapidot, Y. (1998). Relief from job stressors and burnout: Reserve service as a respite. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 577–585.

Fagen, R. (1981). Animal play behavior. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). Positive emotions. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 120–134). New York: Oxford University Press.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062.

Freysinger, V., & Flannery, D. (1992). Women’s leisure: Affiliation, self-determination, empowerment and resistance? Loisir et Societe/Society and Leisure, 15(1), 303–322.

Fritz, C., & Sonnentag, S. (2005). Recovery, health, and job performance: Effects of weekend experiences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10, 187–199.

Fritz, C., & Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: The role of workload and vacation experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 936–945.

Ganster, D., Fusilier, M. R., & Mayes, B. T. (1986). Role of social support in the experience of stress at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 102–110.

Gong, B. (1998). Chinese leisure. Shanghai: Shanghai Antique Press.

Graef, R., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Gianinno, S. M. (1983). Measuring intrinsic motivation in people’s everyday lives. Leisure Studies, 2, 155–168.

Havighurst, R. J. (1961). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 1, 8–13.

Haworth, J. T., & Hill, S. (1992). Work, leisure, and psychological well-being in a sample of young adults. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 2, 147–160.

Haworth, J. T., & Veal, A. J. (2004). Future of work and leisure. London: Routledge.

Headey, B., Veenhoven, R., & Wearing, A. (1991). Top-down versus bottom-up theories of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 24, 81–100.

Heo, J., Kim, J., & Won, Y. S. (2011). Exploring the relationship between internet use and leisure satisfaction among older adults. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 35(1), 43–54.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–524.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1998). Stress, culture, and community: The psychology and philosophy of stress. New York: Plenum Press.

Hutchinson, S. L., Loy, D., Kleiber, D. A., & Dattilo, J. (2003). Leisure as a coping resource: Variations in coping with traumatic injury and illness. Leisure Sciences, 25(2–3), 143–161.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1979). Basic dimensions of definitions of leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 11(1), 28–39.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1980). The social psychology of leisure and recreation. Dubuque, 1A: Wm. C. Brown.

Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1997). A psychological analysis of leisure and health. In J. T. Haworth (Ed.), Work, leisure and well-being (pp. 131–144). London: Routledge.

Iwasaki, Y. (2007). Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: What are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life? Social Indicators Research, 82, 233–264.

Iwasaki, Y. (2008). Pathways to meaning-making through leisure in global contexts. Journal of Leisure Research, 40, 231–249.

Iwasaki, Y., MacKay, K., Mactavish, J., Ristock, J., & Bartlett, J. (2006). Voices from the margins: Stress, active living, and leisure as a contributor to coping with stress. Leisure Sciences, 28, 163–180.

James, Α., & Wells, A. (2003). Religion and mental health: Toward a cognitive-behavioural framework. British Journal of Health Psychology, 8, 359–376.

Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kabneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3–25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306, 1776–1780.

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169–182.

Kaplan, S. (2001). Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior, 33, 480–506.

Kelly, J. R. (1982). Leisure. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kelly, J. R., & Godbey, G. (1992). The sociology of leisure. State College, PA: Venture.

Kelly, J. R., Steinkamp, M. W., & Kelly, J. R. (1987). Later-life satisfaction: Does leisure contribute? Leisure Sciences, 9, 189–200.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932.

King, F. L. (2001). Social dynamics of quilting. World Leisure Journal, 43(2), 26–29.

Kleiber, D. A., Walker, G. J., & Mannell, R. C. (2011). A social psychology of leisure. (2nd ed.) Venture Pub., Incorporated.

Koopman-Boyden, P. G., & Reid, S. L. (2009). Internet/e-mail usage and well-being among 65–84 year olds in New Zealand: Policy implications. Educational Gerontology, 35(11), 990–1007.

Korpela, K., & Kinnunen, U. (2010). How is leisure time interacting with nature related to the need for recovery from work demands? Testing Multiple Mediators, Leisure Sciences, 33(1), 1–14.

Kuo, A., Chew, W. H., & Hooi, W. C. (2007). Occupations of healthy Asian retirees: Impact on quality of life. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 31(3), 1–12.

Lakey, B., & Cronin, A. (2008). Low social support and major depression: Research, theory and methodological issues. In K. S. Dobson & D. Dozois (Eds.), Risk factors for depression (pp. 385–408). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Lakey, B., & Orehek, E. (2011). Relational regulation theory: A new approach to explain the link between perceived social support and mental health. Psychological Review, 118, 482–495.

Larson, R., Mannell, R., & Zuzanek, J. (1986). Daily well-being of older adults with friends and family. Psychology and Aging, 1, 117–126.

Lemon, B. W., Bengtson, V. L., & Peterson, J. A. (1972). An exploration of the activity theory of aging: Activity types and life satisfaction among in-movers to a retirement community. Journal of Gerontology, 27, 511–523.

Lloyd, K. M., & Auld, C. J. (2002). The role of leisure in determining quality of life: Issues of content and measurement. Social Indicators Research, 57(1), 43–71.

Lloyd, K., & Little, D. E. (2010). Self-determination theory as a framework for understanding women’s psychological well-being outcomes from leisure-time physical activity. Leisure Sciences: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 32, 369–385.

Losada, A., Perez-Penaranda, A., Rodriguez-Sanchez, E., Gomez-Marcos, M. A., Ballesteros-Rios, C., Ramos-Carrera, I. R., et al. (2010). Leisure and distress in caregivers for elderly patients. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 50(3), 347–350.

Lounsbury, L. W., & Hoopes, L. L. (1986). A vacation from work: Changes in work and nonwork outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 392–401.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 616–628.

Luhmann, M., Hawkley, L. C., Eid, M., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Time frames and the distinction between affective and cognitive well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(4), 431–441.

Major, W. F. (2001). The benefits and costs of serious running. World Leisure Journal, 43(2), 12–25.

Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2003). Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: Assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 1209–1224.

Maltby, J., & Day, L. (2004). Should never the twain meet? Integrating personality and religious mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 1275–1290.

Mannell, R. C., & Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1987). Psychological nature of leisure and tourism experience. Annals of tourism research, 14(3), 314–331.

Mantero, J. C. (2000). Leisure and tourism. In E. Garcia & F. Lobo (Eds.), Leisure in a globalised society. Sao Paulo: Servico Social Do Comercio.

Martin, L. L., & Tesser, A. (1996). Some ruminative thoughts. In R. S. Wyer Jr (Ed.), Advances in social cognition (Vol. IX, pp. 1–47). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper.

Mausbach, B. T., Cardenas, V., Goldman, S. R., & Patterson, T. L. (2007). Symptoms of psychosis and depression in middle-aged and older adults with psychotic disorders: The role of activity satisfaction. Aging Mental Health, 11(3), 339–345.

Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P. J. Drenth, H. Thierry, & C. J. de Wolff (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (2nd ed., pp. 5–33). Hove: Psychology Press.

Menec, V. H., & Chipperfield, J. G. (1997). Remaining active in later life: The role of locus of control in seniors’ leisure activity participation, health, and life satisfaction. Journal of Aging & Health, 9(1), 105–125.

Mitas, O. (2010). Positive emotions in mature adults’ leisure travel experiences. Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University.

Mojza, E. J., Lorenz, C., Sonnentag, S., & Binnewies, C. (2010). Daily recovery experiences: The role of volunteer work during leisure time. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 60–74.

Nawijn, J. (2010). The holiday happiness curve: A preliminary investigation into mood during a holiday abroad. International Journal of Tourism Research, 12(3), 281–290.

Nawijn, J., Marchand, M. A., Veenhoven, R., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2010). Vacationers happier, but most not happier after a holiday. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 5(1), 35–47.

Neulinger, J. (1974). The psychology of leisure. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas.

Neulinger, J. (1981). Leisure counseling: A commentary. The Counseling Psychologist, 9(3), 69–70.

Nimrod, G. (2008). In support of innovation theory: Innovation in activity patterns and life satisfaction among recently retired individuals. Ageing and Society, 28(6), 831–846.

Oishi, S., Diener, E., Suh, E., & Lucas, R. (1999). Value as a moderator in subjective well-being. Journal of Personality, 67(1), 157–184.

Passmore, A., & French, D. (2001). Development and administration of a measure to assess adolescents’ participation in leisure activities. Adolescence, 36(141), 67–75.

Pieper, J. (1952). Leisure: The basis of culture. New York: Pantheon Books.

Pinquart, M., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2010). Patterns of fulfilment in the domains of work, intimate relationship, and leisure. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 5(2), 147–164.