Abstract

Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in December 2019, scientists worldwide have been looking for a way to control this global threat. One of the most successful and practical solutions has been the development and worldwide distribution of the COVID-19 vaccines. However, in a small percentage of cases, vaccination can lead to de novo development or exacerbation of immune or inflammatory conditions such as psoriasis. Due to the immunomodulatory nature of this disease, people affected by psoriasis and other related skin conditions have been encouraged to receive COVID-19 vaccines, which are immunomodulatory by nature. As such, dermatological reactions are possible in these patients, and cases of onset, exacerbation or change in the type of psoriasis have been observed in patients administered with COVID-19 vaccines. Considering the rarity and minor nature of some of these cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccination, there is a general consensus that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the potential risks of experiencing such side effects. Nevertheless, healthcare workers who administer vaccines should be made aware of the potential risks and advise recipients accordingly. Furthermore, we suggest careful monitoring for potentially deleterious autoimmune and hyperinflammatory responses using point-of-care biomarker monitoring.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in December 2019. This is the third coronavirus transmitted from zoonotic species to humans after the H1N1 influenza outbreak in 2016 [1]. COVID-19 is associated chiefly with self-limiting upper respiratory tract infections. However, a small but significant proportion of patients develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which cannot be treated effectively and may increase risk of death [2]. In cases of severe COVID-19, the host immune system appears to respond excessively, producing a damaging hyperinflammatory response known as a cytokine storm [3].

Potentially the most effective way of halting the spread of viral infections is through the development and deployment of approved vaccines. As of October 18, 2022, more than 68% of the world population have been administered at least one dose of an approved COVID-19 vaccine [4]. However, the rate of vaccination has declined [4], and there is still a significant proportion of populations around the world that show vaccine hesitancy [5]. One factor that may affect public confidence in vaccine uptake is the potential of long- and short-term adverse effects [6,7,8]. Although uncommon, some cases of new-onset psoriasis and exacerbation of existing ones have been reported around the world, following a COVID-19 vaccination [9,10,11,12,13,14]. However, it should be noted that both new psoriasis cases and exacerbation of existing ones were reported even before rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines [15,16,17,18]. This suggests the involvement of a common underlying mechanism in psoriasis, COVID-19 infection and vaccination. The most likely link is through immune and inflammatory pathway modulation as all of these work as a result of effects on these systems, including through activation of autoimmune mechanisms [19,20,21,22,23].

In this study, we have evaluated studies on the effect of various COVID-19 vaccines as a potential causative factor in the de novo appearance or exacerbation of psoriasis in the individuals who received these. We also make recommendations on how to deal with this potential issue while at the same time maintaining an effective vaccination approach.

2 Methods

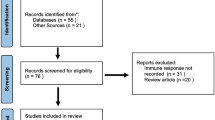

Data were collected from papers published in PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar and Cochrane library for Clinical Studies. This required that the papers were published in English up to January, 2022. Search terms included “psoriasis” OR “dermatological reactions” AND “COVID-19” OR “COVID-19 vaccines” AND “adverse reaction” OR “side effects” AND “immunological response.”

3 Psoriasis and Correlation with COVID-19

Psoriasis is an inflammatory skin disease that affects 0.09–11.43% of people in different countries around the world [24]. Psoriasis patients may be prescribed systemic immunomodulatory or immunosuppressive treatments depending on location and severity of the lesions or if they are resistant to topical treatments [25]. However, these therapies have been associated with the increased risk of infections, and there has been considerable controversy regarding the potential of increased susceptibility of psoriasis patients on such treatments to COVID-19 infections and/or a more serious disease course [26,27,28,29,30,31]. In this section, we review some of the relevant studies addressing this controversy.

Kara Polat et al. found no difference in the incidence, length of hospital stay, intensive care unit (ICU) admittance or death outcomes in psoriasis patients on immunosuppressive or biologic treatments with COVID-19 infections compared to those who had not been treated with these compounds [32]. None of the other tested potential risk factors that were assessed had an influence on COVID-19 disease trajectory apart from the presence of diabetes. However, there was an exacerbation of psoriasis with COVID-19 infections.

A retrospective multicentre study in Italy of 5206 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis on biological therapies found no deaths from COVID-19 and four hospitalizations for COVID-related interstitial pneumonia, which did not differ from the general population [33]. However, the authors acknowledged limitations due to the lack of standardization of the control group.

Carugno et al. evaluated 159 psoriasis patients during the first 45 days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Lombardy region of Italy for SARS-CoV-2 infections [34]. They found no serious cases of COVID-19 and no difference in patients who continued or did not continue their psoriasis treatment.

A case–control study performed in 2020 by Damiani et al. of 1193 psoriasis patients in Lombardy receiving small molecules or biological drugs found that 22 of these tested positive for COVID-19, with 5 of these being hospitalized and none admitted to the ICU or who died [35]. In comparison to the general population, the researchers found that patients were at higher risk to test positive for COVID-19 and hospitalized. These findings suggested that treatment with biologic or immunosuppressive therapeutics may increase the risk of contracting mild forms of COVID-19 disease.

Other studies showed de novo or exacerbation of psoriasis in COVID-19 cases who were not on immunosuppressive therapies. A case study of a 38-year-old man with a single psoriatic plaque but who had received no treatment for this condition was diagnosed with COVID-19 infection after a nasopharyngeal test [36]. Six days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms, several psoriatic lesions formed on his knee with no improvement after 22 days. After this, treatment with topical betamethasone cream led to significant clinical improvement after 2 weeks. Another case report of a 25-year-old male diagnosed with a COVID-19 infection developed multiple psoriatic lesions 15 days later [37]. As above, treatment with topical betamethasone led to recovery.

Taken together, these studies provide no evidence that biologic or immunosuppressive treatments increase the risk of COVID-19 infection or severity of disease course. However, they do suggest that COVID-19 disease can lead to de novo eruptions or exacerbations of existing psoriatic lesions. This was supported by a study covering the first (February 15, 2020 to June 30, 2020) and second (October 1, 2020 to January 31, 2021) waves of the pandemic in France [38]. This investigation found that COVID-19 patients who had received systemic treatments for psoriasis did not show an increased risk of in-hospital mortality due to COVID-19 infection.

4 Efficacy and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Patients with Psoriasis

Wack et al. reviewed the evidence related to COVID-19 vaccine safety and efficacy in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases [39]. They found no evidence to support the point that these patients are at a higher risk of harmful side effects from a COVID-19 vaccination compared to healthy controls. However, they could not determine if patients on biologics or immunosuppresants produce a sufficient immune response to the vaccine, as this may depend on the specific indication and therapeutic employed.

A study conducted by Geisen et al. showed that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines produce antibodies with neutralizing activity in healthy controls as well as in patients who were on immunosuppressant therapies for chronic inflammatory conditions [40]. However, the immunoglobulin G (IgG) titres were significantly lower in the immunosuppressant-treated patients compared to controls. It should be noted that vaccination did not lead to significant side effects or disease flare-ups in the immunosuppressed group.

Along the same lines, another study found that patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases who received the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine produced slower antibody responses compared to the control group, and a higher proportion of these patients showed no detectable response [41]. Furthermore, those patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases who had not been treated showed a similar diminished response, suggesting that this effect may be linked to the disease rather than to a treatment effect.

Skroza et al. evaluated the safety of COVID-19 vaccination in psioriasis patients who had received biological or immunosuppressive treatment for at least 24 weeks [42]. The study found that all patients showed a similar reduction in their psoriasis area severity index scores, and this did not differ between vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals. In addition, no adverse effects were detected in either group.

In another study, Damiani et al. evaluated four psoriatic cases who took biological or immunomodulatory medications and received two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [43]. This showed that none of the patients showed changes in cutaneous manifestations or a psoriasis flare up. Furthermore, all patients showed an effective response to the vaccine.

In order to promote optimal treatment of patients with psoriasis during the pandemic, the National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guideline has proposed that patients with psoriasis should receive their COVID-19 vaccine in the shortest possible time while continuing with their biological or immunomodulatory treatments drugs [44]. However, this proposal stipulates that the ultimate judgement should be made by the treating clinician and the patient due to variability of psoriatic diseases and the medications used to treat them.

5 Psoriasis After COVID-19 Vaccination

5.1 COVID-19 Vaccination Leading to De Novo Psoriasis

A number of studies have reported on cases of individuals who developed different forms of psoriasis for the first time after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine (see Table 18.1). This includes de novo psoriasis cases following the first [46, 46] or second [46] dose of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. In addition, there have been reports of new psoriasis eruptions following the first [47, 48] or second [49] dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Although the mechanism for these spontaneous eruptions is not clear, it is possible that it is linked to dysregulation of immune system due to the virus or vaccine components, as proposed by Gunes et all for other vaccines such as influenza, BCG and tetanus-diphtheria vaccines [50]. In addition, mRNA vaccines such as Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can lead to increased levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and Th17 cell activation, which are known to be involved in the pathological mechanism of psoriasis [51, 52]. Even though these cases of de novo medical professionals are still advised to pay close attention to side effects and take appropriate measures in the treatment of the clinical condition on a case-by-case basis.

5.2 COVID-19 Vaccinations Which Exacerbates Psoriasis

5.2.1 Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA Vaccine

A number of studies have reported on exacerbations or flare-ups of psoriasis that may be linked to vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine: Durmaz et al. described three different cases where psoriasis was exacerbated after the first, second and third doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [53]. A case study also reported exacerbation of existing psoriasis in a 40-year-old man after vaccination with the first dose of the same vaccine [54]. Two cases of underlying dermatitis were reported to be exacerbated upon receipt of the third dose of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [55]. In a recent study, Michkowska et al. reported a case of a 65-year-old male with a history of hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with nivolumab and poorly controlled psoriasis that was exacerbated one week after he received the first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [56]. Another case study reported on a man who developed psoriatic lesions on the lower legs 5 days after a second dose of this vaccine [52]. Finally, one study reported on a 51-year-old man whose existing psoriatic lesions enlarged after receipt of his first dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [57]. The same report described the case of a second man with a complaint of skin rash that started on his buttocks 1 month after the second dose of inactivated CoronaVac vaccine [57].

5.2.2 Oxford/AstraZeneca Vaccine

There have also been reports of exacerbated psoriasis conditions linked to vaccination with the AstraZeneca vaccine. For example, Fang et al. reported a case of a 34-year-old woman with a history of psoriasis who was being treated successfully with biologic and immunosuppressant drugs [58]. One week after being injected with the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, an erythematous scaly plaque was seen around the injection site and psoriasis plaques developed on her trunk and extremities. Another case presented by Nagrani et al. described a 56-year-old woman with a history of psoriasis who showed a flare-up of psoriatic lesions after receiving her first dose of the Covishield version of the AstraZeneca vaccine [46].

5.2.3 Studies Carried Out at Single Centres

In a retrospective study, Koumaki et al. identified 12 patients at a single centre who showed an exacerbation in their psoriasis condition after receiving either the Pfizer-BioNTech or AstraZeneca vaccine [59]. Likewise, Wei et al. carried out a retrospective analysis at a single centre in New York to investigate cases of new-onset or exacerbation of existing psoriasis after COVID-19 vaccination [60]. They identified 7 patients who showed new onset or psoriasis flare-ups of pre-existing psoriasis after receiving either the Modena or Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccines. Sotiriou et al. reported 14 cases of psoriasis flares from a single centre after patients were vaccinated with either of the Pfizer, Moderna or AstraZeneca vaccines [61]. Similarly, Megna et al. reported on 11 cases of psoriasis exacerbation over a 6-month period in early 2021 following vaccination with Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna or Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines [62].

In a larger study, Huang et al. recruited 32 volunteers with psoriasis who had never been immunized and 51 psoriasis patients who had been vaccinated who had been vaccinated with either the Moderna or AstraZeneca vaccine [63]. They observed 15 cases of exacerbations that occurred within 9 days of vaccination compared to two cases in the non-vaccinated control group. Taken together these results suggest that there is some risk of flare-ups or exacerbations of pre-existing psoriasis conditions following the administration of many of the COVID-19 vaccines.

5.3 COVID-19 Vaccination Changing Type of Psoriasis

Onsun et al. reported on a case involving a 72-year-old male patient with a history of plaque psoriasis using a topical treatment for his condition [64]. Four days after receiving the first dose of the CoronaVac vaccine, he manifested a number of alterations in his condition including desquamation, diffuse erythema and coalescing pustules. Another study showed that two cases of mild plaque-type psoriasis appeared to develop into the pustular palmoplantar psoriasis form one month after administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine [65]. Finally, Quattrini et al. reported the case of an 83-year-old female with a history of palmoplantar psoriasis. Two days after being administered her second dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, she presented to the hospital with symptoms of stiffness, swelling and desquamation of palmar skin of both hands along with oedema on the back of the left hand and wrist [66].

6 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The current vaccines currently approved by the WHO consist of four different types [67] which can be classified as:

-

1.

mRNA (spike protein)

-

(a)

Comirnaty (Pfizer/BioNTech)

-

(b)

Spikevax (Moderna)

-

(a)

-

2.

Viral vector (spike protein)

-

(a)

Vaxzevria (Oxford/AstraZeneca)

-

(b)

Covishield (Oxford/AstraZeneca)

-

(c)

Jcovden (Janssen),

-

(d)

Convidecia (CanSino)

-

(a)

-

3.

Inactivated virus

-

(a)

Covilo (Sinopharm)

-

(b)

CoronaVac (Sinovac)

-

(c)

Covaxin (Bharat Biotech)

-

(a)

-

4.

Recombinant spike protein

-

(a)

COVOVAX (Novavax)

-

(b)

Nuvaxovid (Novavax)

-

(a)

In addition, there are adapted bivalent versions of authorized COVID-19 vaccines from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Biotech using the mRNA spike protein strategy for broader protection against the variants [68]:

-

1.

Pfizer/BioNTech

-

(a)

Comirnaty bivalent – Original + Omicron BA.1 spike protein (Authorized: September 1, 2022)

-

(b)

Comirnaty bivalent – Original + Omicron BA.4-5 (Authorized: September 9, 2022)

-

(a)

-

2.

Moderna Biotech

-

(a)

Spikevax bivalent Original/Omicron BA.1 (Authorized: September 1, 2022)

-

(b)

Spikevax bivalent Original/Omicron BA.4-5 (Under evaluation: from September 26, 2022)

-

(a)

Like all medications, vaccines can cause side effects such as psoriasis [50, 69]. Since the COVID-19 vaccines work in different ways, this is likely to occur via some overlapping and some distinct mechanisms. However, this review revealed that most of the above types of COVID-19 vaccines were associated with psoriatic side effects. Also, given that psoriasis cases were reported in response to SARS-CoV-2 infections before the COVID-19 vaccines were rolled out [15,16,17,18], a likely common mechanism is through perturbations in immune and/or inflammatory pathways, including potential autoimmune responses [19,20,21,22,23]. This suggests that individuals with pre-existing psoriasis or other autoimmune-related conditions should be advised and then monitored for worsening of their conditions after a COVID-19 infection or vaccination. In cases where a de novo eruption or exacerbation does occur, treatment with some biologics, immunosuppressive agents and anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful [21, 70, 71]. However, some of these could also lead to a worsening of the condition, which suggests that techniques for monitoring potential autoimmune and pro-inflammatory effects should be applied.

Four psoriasis-associated autoantigens have been identified as cathelicidin LL-37, melanocyte A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease domain containing thrombospondin type 1 motif-like 5 (ADAMTSL5), phospholipase A2 group IVD (PLA2G4D) and keratin 17, and autoreactive T cells against these have been found in some psoriasis patients [72]. Another study reported on the discovery of autoantibodies against LL-37 and ADAMTSL5 associated with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, suggesting a potential role of these autoantibodies in disease pathogenesis [73]. We suggest the use of screening panels for monitoring the levels of these and other autoantibodies, using platforms such as those developed by the German companies CellTrend [74] and EUROIMMUN [75]. Other technologies such as multiplex immunoassay [76] and cytokine arrays [77] could be used to detect inflammation-related changes for disease detection and monitoring. For more rapid analyses in a doctor’s office or clinic, lab-on-a-chip devices incorporating rapid and sensitive tests for some of these biomarkers could be employed for point-of-care-testing [80,81,80].

At this stage, no specific emphasis can be given on the cause of psoriasis onset or exacerbation based on the type of COVID-19 vaccine. The matter is further complicated by the fact that some cases were apparently caused in people who did not have a history of psoriasis, and some existing psoriasis cases had received biological or immunosuppressant drug therapies, while others were in remission. In addition, where cases emerged or were exacerbated, these varied in their degree of severity or chronicity. Also, the low severity of the disease in some cases was so low that receiving an emollient was sufficient for the symptom relief. Furthermore, 0.1–0.5% of the European population have reported any adverse responses associated with a COVID-19 vaccination [81].

Considering that cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccination are rare and, when they do occur, they are mostly minor and self-limiting, there is a general consensus that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the potential risks of experiencing such side effects [63, 84,85,86,87,86]. This is especially true since bivalent vaccines are now available which are capable of neutralizing the highly infectious omicron variant, maximizing the benefit-to-risk ratio. Nevertheless, healthcare workers administering the vaccines must be made aware of these potential risks and advise the recipients accordingly. To add an extra layer of safety, careful monitoring for potentially deleterious autoimmune and hyperinflammatory responses can be employed. These can include screening for the presence of autoantibodies and inflammation-related molecules for both risk assessment and for monitoring patient responses to either COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 vaccination or biologic and anti-inflammatory treatments.

References

El Zowalaty ME,Järhult JD (2020) From SARS to COVID-19: A previously unknown SARS-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of pandemic potential infecting humans–Call for a One Health approach. One Health 9:100124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100124

Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, et al (2020) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents 55(3):105924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924

Kempuraj D, Selvakumar GP, Ahmed ME, et al. (2020) COVID-19, mast cells, cytokine storm, psychological stress, and neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist 26(5–6):402–414

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations. Accessed October 18, 2022

Lazarus JV, Wyka K, White TM, et al (2022) Revisiting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy around the world using data from 23 countries in 2021. Nat Commun 13(1):3801. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-31441-x

Mushtaq HA, Khedr A, Koritala T, et al (2022) A review of adverse effects of COVID-19 vaccines. Infez Med. 30(1):1–10

Rahman MM, Masum MHU, Wajed S, Talukder A (2022) A comprehensive review on COVID-19 vaccines: development, effectiveness, adverse effects, distribution and challenges. Virusdisease 33(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13337-022-00755-1

Chi WY, Li YD, Huang HC, Chan TEH, et al (2022) COVID-19 vaccine update: vaccine effectiveness, SARS-CoV-2 variants, boosters, adverse effects, and immune correlates of protection. J Biomed Sci 29(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-022-00853-8

Musumeci ML, Caruso G, Trecarichi AC, Micali G (2022) Safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in psoriatic patients treated with biologics: A real life experience. Dermatol Ther 35(1):e15177. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15177

Piros ÉA, Cseprekál O, Görög A, et al (2022) Seroconversion after anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations among moderate-to-severe psoriatic patients receiving systemic biologicals-Prospective observational cohort study. Dermatol Ther 35(5):e15408. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15408

Seirafianpour F, Pourriyahi H, Gholizadeh Mesgarha M, et al (2022) A systematic review on mucocutaneous presentations after COVID-19 vaccination and expert recommendations about vaccination of important immune-mediated dermatologic disorders. Dermatol Ther 35(6):e15461. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15461

Tran TNA, Nguyen TTP, Pham NN, et al (2022) New onset of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination. Dermatol Ther 35(8):e15590. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15590

Chhabra N, C AG (2022) A case of de novo annular-plaque type psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. Curr Drug Saf.. https://doi.org/10.2174/1574886317666220613163327

Shakoei S, Kalantari Y, Nasimi M, et al (2022) Cutaneous manifestations following COVID-19 vaccination: A report of 25 cases. Dermatol Ther 35(8):e15651. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15651

Brunasso AMG, Massone C (2020) Teledermatologic monitoring for chronic cutaneous autoimmune diseases with smartworking during COVID-19 emergency in a tertiary center in Italy. Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13495. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13695

Buhl T, Beissert S, Gaffal E, et al (2020) COVID-19 and implications for dermatological and allergological diseases. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 18(8):815–824

Drenovska K, Schmidt E, Vassileva S (2020) Covid-19 pandemic and the skin. Int J Dermatol 59(11):1312–1319

Molaee H, Allahyari F, Emadi SN, et al (2021) Cutaneous manifestations related to the COVID-19 pandemic: a review article. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 40(2):168–174

Krueger JG, Bowcock A (2005) Psoriasis pathophysiology: current concepts of pathogenesis. Ann Rheum Dis 64 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):ii30-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.031120

Hari G, Kishore A, Karkala SRP (2022) Treatments for psoriasis: A journey from classical to advanced therapies. How far have we reached? Eur J Pharmacol 929:175147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175147

Al-Beltagi M, Saeed NK, Bediwy AS (2022) COVID-19 disease and autoimmune disorders: A mutual pathway. World J Methodol 12(4):200–223

Rodríguez Y, Rojas M, Beltrán S, et al (2022) Autoimmune and autoinflammatory conditions after COVID-19 vaccination. New case reports and updated literature review. J Autoimmun 132:102898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2022.102898

Darmarajan T, Paudel KR, Candasamy M, et al (2022) Autoantibodies and autoimmune disorders in SARS-CoV-2 infection: pathogenicity and immune regulation. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 29(36):54072–54087

World Health Organization; Global Report on Psoriasis (2016). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/204417/9789241565189_eng.pdf.psoriasis?sequence=1. Accessed October 18, 2022

Mayo Clinic; Psoriasis; Treatment; Oral or Injected Medications. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/psoriasis/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20355845#:~:text=Options%20include%20apremilast%20(Otezla)%2C,)%20and%20certolizumab%20(Cimzia). Accessed October 19, 2022

Di Lernia V (2020) Antipsoriatic treatments during COVID-19 outbreak. Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13345. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13345

Abdelmaksoud A, Goldust M, Vestita M (2020) Comment on "COVID-19 and psoriasis: Is it time to limit treatment with immunosuppressants? A call for action". Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13360. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13360

Bardazzi F, Loi C, Sacchelli L, Di Altobrando A (2020) Biologic therapy for psoriasis during the covid-19 outbreak is not a choice. J Dermatolog Treat 31(4):320–321

Megna M, Ruggiero A, Marasca C, Fabbrocini G (2020) Biologics for psoriasis patients in the COVID-19 era: more evidence, less fears. J Dermatolog Treat 31(4):328–329

Megna M, Napolitano M, Patruno C, Fabbrocini G (2020) Biologics for psoriasis in COVID-19 era: What do we know? Dermatol Ther 33(4):e13467. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13467

Naldi L (2021) Risk of infections in psoriasis. A lesson to learn during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Br J Dermatol 184(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19190

Kara Polat A, Oguz Topal I, Karadag AS, et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis: A multicenter study in Istanbul. Dermatol Ther 34(1):e14691. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14691

Gisondi P, Facheris P, Dapavo P, et al (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients with chronic plaque psoriasis being treated with biological therapy: the Northern Italy experience. Br J Dermatol 183(2):373–374

Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F, et al (2020) COVID-19 and biologics for psoriasis: A high-epidemic area experience-Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol 83(1):292–294

Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL, Malagoli P (2020) Biologics increase the risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: Real-life data from a large cohort during red-zone declaration. Dermatol Ther 33(5):e13475. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13475

Gananandan K, Sacks B, Ewing I (2020) Guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep 13(8):e237367. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-237367

Rouai M, Rabhi F, Mansouri N, et al (2021) New-onset guttate psoriasis secondary to COVID-19. Clin Case Rep 9(7):e04542. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.4542

Penso L, Dray-Spira R, Weill A, et al (2022) Psoriasis-related treatment exposure and hospitalization or in-hospital mortality due to COVID-19 during the first and second wave of the pandemic: cohort study of 1 326 312 patients in France. Br J Dermatol 186(1):59–68

Wack S, Patton T, Ferris LK (2021) COVID-19 vaccine safety and efficacy in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disease: Review of available evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol 85(5):1274–1284

Geisen UM, Berner DK, Tran F, et al (2021) Immunogenicity and safety of anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with chronic inflammatory conditions and immunosuppressive therapy in a monocentric cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 80(10):1306–1311

Simon D, Tascilar K, Fagni F, et al (2021) SARS-CoV-2 vaccination responses in untreated, conventionally treated and anticytokine-treated patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 80(10):1312–1316

Skroza N, Bernardini N, Tolino E, et al (2021) Safety and Impact of Anti-COVID-19 Vaccines in Psoriatic Patients Treated with Biologics: A Real Life Experience. J Clin Med 10(15):

Damiani G, Allocco F, Malagoli P (2021) COVID-19 vaccination and patients with psoriasis under biologics: real-life evidence on safety and effectiveness from Italian vaccinated healthcare workers. Clin Exp Dermatol 46(6):1106–1108

Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al (2021) National Psoriasis Foundation COVID-19 Task Force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: Version 2-Advances in psoriatic disease management, COVID-19 vaccines, and COVID-19 treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol 84(5):1254–1268

Elamin S, Hinds F,Tolland J (2022) De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol 47(1):153–155

Nagrani P, Jindal R, Goyal D (2021) Onset/flare of psoriasis following the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 Corona virus vaccine (Oxford-AstraZeneca/Covishield): Report of two cases. Dermatol Ther 34(5):e15085. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15085

Song WJ, Lim Y, Jo SJ (2022) De novo guttate psoriasis following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. J Dermatol 49(1):e30–e31

Lehmann M, Schorno P, Hunger RE, et al (2021) New onset of mainly guttate psoriasis after COVID-19 vaccination: a case report. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 35(11):e752–e755

Ricardo JW, Lipner SR (2021) Case of de novo nail psoriasis triggered by the second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 COVID-19 messenger RNA vaccine. JAAD Case Rep 1718–1720

Gunes AT, Fetil E, Akarsu S, et al (2015) Possible Triggering Effect of Influenza Vaccination on Psoriasis. J Immunol Res 2015:258430. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/258430

Wu PC, Huang IH, Wang CW, et al (2022) New Onset and Exacerbations of Psoriasis Following COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review. Am J Clin Dermatol 23(6):775–799

Krajewski PK, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC (2021) Psoriasis flare-up associated with second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT16B2b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 35(10):e632–e634

Durmaz I, Turkmen D, Altunisik N,Toplu SA (2022) Exacerbations of generalized pustular psoriasis, palmoplantar psoriasis, and psoriasis vulgaris after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: A report of three cases. Dermatol Ther 35(4):e15331. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15331

Perna D, Jones J, Schadt CR (2021) Acute generalized pustular psoriasis exacerbated by the COVID-19 vaccine. JAAD Case Rep 17:1–3

Phuan CZY, Choi EC-E,Oon HH (2022) Temporary exacerbation of pre-existing psoriasis and eczema in the context of COVID-19 messenger RNA booster vaccination: A case report and review of the literature. JAAD International 6:94–96

Mieczkowska K, Kaubisch A,McLellan BN (2021) Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination in a patient previously treated with PD-1 inhibitor. Dermatol Ther 34(5):e15055. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15055

Bostan E, Elmas L, Yel B,Yalici-Armagan B (2021) Exacerbation of plaque psoriasis after inactivated and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: A report of two cases. Dermatol Ther 34(6):e15110. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15110

Fang WC, Chiu LW,Hu SC (2021) Psoriasis exacerbation after first dose of AstraZeneca coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine. J Dermatol 48(11):e566–e567

Koumaki D, Krueger-Krasagakis SE, et al (2022) Psoriasis flare-up after AZD1222 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: report of twelve cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36(6):e411–e415

Wei N, Kresch M, Elbogen E,Lebwohl M (2022) New onset and exacerbation of psoriasis after COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Reports 19:74–77

Sotiriou E, Tsentemeidou A, Bakirtzi K, Lallas A, Ioannides D,Vakirlis E (2021) Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: a report of 14 cases from a single centre. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 35(12):e857–e859

Megna M, Potestio L, Gallo L, Caiazzo G, Ruggiero A,Fabbrocini G (2022) Reply to “Psoriasis exacerbation after COVID-19 vaccination: report of 14 cases from a single centre” by Sotiriou E et al. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 36(1):e11–e13

Huang YW, Tsai TF (2021) Exacerbation of Psoriasis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: Report From a Single Center. Front Med (Lausanne) 8:812010. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.812010

Onsun N, Kaya G, Işık BG,Güneş B (2021) A generalized pustular psoriasis flare after CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccination: Case report. Health Promot Perspect 11(2):261–262

Piccolo V,Russo T,Mazzatenta C,Bassi A,Argenziano G,Cutrone M et al. (2022) COVID vaccine-induced pustular psoriasis in patients with previous plaque type psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36(5):e330–e332

Quattrini L, Verardi L, Caldarola G, Peluso G, De Simone C,D’Agostino M (2021) New onset of remitting seronegative symmetrical synovitis with pitting oedema and palmoplantar psoriasis flare-up after Sars-Cov-2 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 35(11):e727–e729

World Health Organization; Types of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/covid-19-vaccines. Accessed October 2022

European Medicines Agency; Adapted COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/covid-19-vaccines-authorised. Accessed October 20, 2022

Sbidian E, Eftekahri P, Viguier M, et al (2014) National survey of psoriasis flares after 2009 monovalent H1N1/seasonal vaccines. Dermatology 229(2):130–135

Jara LJ, Vera-Lastra O, Mahroum N, et al (2022) Autoimmune post-COVID vaccine syndromes: does the spectrum of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome expand? Clin Rheumatol 41(5):1603–1609

Aryanian Z, Balighi K, Afshar ZM, et al (2022) COVID vaccine recommendations in dermatologic patients on immunosuppressive agents: Lessons learned from pandemic. J Cosmet Dermatol https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.15448

Ten Bergen LL, Petrovic A, Aarebrot AK, Appel S (2020) Current knowledge on autoantigens and autoantibodies in psoriasis. Scand J Immunol 92(4):e12945. https://doi.org/10.1111/sji.12945

Yuan Y, Qiu J, Lin ZT, et al (2019) Identification of novel autoantibodies associated with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 71(6):941–951

POTS/Long Covid-diagnostics; CellTrend; https://www.celltrend.de/en/pots-cfs-me-sfn/. Accessed September 4, 2022

EUROIMMUN Autoantibodies in neurological diseases. https://www.euroimmun.com/documents/Indications/Autoimmunity/Neurology/MAG_myelin_GAD/FA_1111_I_UK_A.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2022

Guest PC, Abbasifard M, Jamialahmadi T, et al (2022) Multiplex Immunoassay for Prediction of Disease Severity Associated with the Cytokine Storm in COVID-19 Cases. Methods Mol Biol 2511:245–256

Zahedipour F, Guest PC, Majeed M, et al (2022) Evaluating the Effects of Curcumin on the Cytokine Storm in COVID-19 Using a Chip-Based Multiplex Analysis. Methods Mol Biol 2511:285–295

Einhorn L, Krapfenbauer K (2015) HTRF: a technology tailored for biomarker determination-novel analytical detection system suitable for detection of specific autoimmune antibodies as biomarkers in nanogram level in different body fluids. EPMA J 6:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13167-015-0046-y

Peter H, Wienke J, Bier FF (2017) Lab-on-a-Chip Multiplex Assays. Methods Mol Biol 1546:283–294

Peter H, Mattig E, Guest PC, Bier FF (2022) Lab-on-a-Chip Immunoassay for Prediction of Severe COVID-19 Disease. Methods Mol Biol 2511:235–244

European Medicines Agency; Safety of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/public-health-threats/coronavirus-disease-covid-19/treatments-vaccines/vaccines-covid-19/safety-covid-19-vaccines. Accessed October 20, 2022

McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, et al (2021) Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: A registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 85(1):46–55

Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, et al (2022) Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol 186(1):142–152

Cebeci Kahraman F, Savaş Erdoğan S, et al (2022) Cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination in Turkey: A multicenter study. J Cosmet Dermatol 21(9):3692–3703

Bostan E, Yel B, Karaduman A (2022) Cutaneous adverse events following 771 doses of the inactivated and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: A survey study among health care providers. J Cosmet Dermatol 21(9):3682–3688

Falotico JM, Desai AD, Shah A, et al (2022) Curbing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy from a Dermatological Standpoint: Analysis of Cutaneous Reactions in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) Database. Am J Clin Dermatol 23(5):729–737

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Khanahmadi, M., Khayatan, D., Guest, P.C., Hashemian, S., Abdolghaffari, A.H., Sahebkar, A. (2023). The Relationship Between Psoriasis, COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination During Treatment of Patients. In: Guest , P.C. (eds) Application of Omic Techniques to Identify New Biomarkers and Drug Targets for COVID-19. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology(), vol 1412. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28012-2_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28012-2_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-28011-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-28012-2

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)