Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review aims to evaluate the spectrum of cutaneous reactions after both SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination while simultaneously understanding the evolution of the field of dermatology in the face of an ongoing pandemic.

Recent Findings

The most commonly reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 infection in the literature to date include morbilliform or maculopapular rashes, chilblains, and urticaria. The incidence of cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination was 9% in larger cohort studies and more commonly occurred after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines than adenovirus vector vaccines. The most frequently reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccines were delayed large local reactions, local injection site reactions, urticarial eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions.

Summary

With the ongoing pandemic, and continued development of new COVID-19 variants and vaccines, the landscape of cutaneous reactions continues to rapidly evolve. Dermatologists have an important role in evaluating skin manifestations of the virus, as well as discussion and promoting COVID-19 vaccination for their patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In November 2019, the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus completely changed the landscape of medicine as we know it. As of July 2022, there have been over 569 million cases worldwide with over 6.3 million deaths due to coronavirus-2019 (COVID-19) [1]. While over 10 billion COVID-19 vaccines have been given, 33% of the worldwide population still remains unvaccinated [1].

COVID-19 was initially recognized as a respiratory virus [2, 3], characterized by fever, coughing, general weakness, fatigue, headache, myalgia, sore throat, coryza, dyspnea, nausea, diarrhea, and anorexia [4]. With new variants, symptom frequency has changed, such as reductions in anosmia and increases in sore throat [5]. Early reports of skin manifestations of COVID-19 varied widely, from 2% to 40% of patients with SARS-CoV-2, depending on the population evaluated [6,7,8,9]. Larger studies out of the UK and France have both found the frequency of cutaneous manifestations in the early waves of the pandemic to be present in ~ 9% of individuals testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 [6, 8].

More than 30 different rashes have been identified after SARS-CoV-2 infection, potentially due to heterogeneous host immune responses to the virus [10, 11••, 12, 13••]. COVID-19 vaccines have produced a similarly wide array of cutaneous reactions, from delayed large local reactions to chronic spontaneous urticaria to vaccine-related eruptions of papules and plaques (V-REPP) [14]. Assigning causality to skin eruptions after COVID-19 vaccination can be particularly challenging, with at least one group of authors recommending that eruptions need to begin within 21 days of vaccination to be considered associated with the vaccine [15].

With the stream of new SARS-CoV-2 variants and distribution of additional COVID-19 booster doses, we can expect to see new dermatological patterns continuing to emerge. This review aims to evaluate the spectrum of cutaneous reactions after both SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination and understand the evolution of the field of dermatology in the face of an ongoing pandemic.

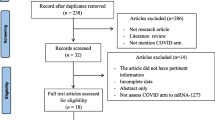

Methods

A PubMed search for articles published between November 30, 2019 and May 1, 2022 was conducted for relevant literature outlining cutaneous reactions to the COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccines. The search utilized the following key terms: “cutaneous reactions,” “COVID-19 infection,” “COVID-19 vaccines,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “morbilliform,” “urticaria,” “local reactions,” “pruritus,” “pernio,” “chilblains,” “zoster,” “vesicular,” “erythema multiforme,” “V-REPP,” “bullous disease,” and “vasculitis.” The name of each COVID-19 vaccine was further included with the term “cutaneous reactions” to locate any additional vaccine-related articles. The search terms, “mRNA-1273,“ “Moderna,” “BNT162b2,” “Pfizer,” “AZD1222,” “AstraZeneca,” “JNJ-78436735,” “J&J,” and “CoronaVac” were included because they encompass the most common COVID-19 vaccines.

All literature on cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 infection and vaccines were included. This includes case reports, case series, clinical trials, observational reports, and epidemiological studies. Literature on the changes to dermatology practice since the start of the pandemic and non-cutaneous reactions were excluded. Relevant article selection and data extraction were performed by the primary author (R.S.). The combined PubMed search criteria yielded a total of 224 peer-reviewed journal articles. Of these articles, a total of 136 sources were included in the review.

Cutaneous Reactions to SARS-CoV-2 Infections

The AAD/ILDS COVID-19 registry and the Spanish Academy of Dermatology nationwide case collection represent two of the largest provider-facing collections of cases of COVID-19 cutaneous manifestations. Combined, these sources represent thousands of cases of cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 [11••, 13••]. The most commonly reported cutaneous reactions in the literature to date include morbilliform or maculopapular rashes, chilblains, and urticaria. In this section, we will discuss the most frequently reported cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1).

Morbilliform/Maculopapular Rash

Morbilliform reactions after SARS-CoV-2 infection have been described as maculopapular erythema predominantly involving the trunk with associated pruritus [11••, 13••]. Morbilliform or maculopapular rash was the most commonly noted skin manifestation reported in registry and case collection-based studies of COVID-19 skin manifestations [11••]. Freeman et al. reports 22% of cutaneous reactions to the infection in the AAD/ILDS international registry were described as morbilliform rashes (COVID-19 laboratory confirmed) [11••]. Similarly, Galván Casas et al. reported maculopapular reactions in 47% of patients in their nationwide case collection [13••]. The overall incidence among all patients with COVID-19 is not precisely known; a UK cohort study found 6.8% of patients with positive COVID-19 testing had a body rash, but this was self-reported and not further characterized in detail [6]. Patients presenting with morbilliform or maculopapular reactions were commonly treated with topical steroids with resolution in an average of 8.6 days [11••].

Acro-ischemia

Acro-ischemic skin lesions originate from vascular injury and can more commonly present with the clinical picture of necrosis or gangrene and less commonly with atypical Raynaud’s, pseudo-pernio, microcirculatory ischemia, or dry gangrene with arteriosclerosis obliterans as described in one study [16]. A small study of 24 patients reports that acral ischemia was presents in 1.2% of patients with a predominance in patients with more severe presentations of COVID-19 [16, 17].

Pernio/Chilblains

Pernio/chilblains after SARS-CoV-2 infection, often known as “COVID-toes” in the lay press, commonly presents as asymmetric purpuric lesions on the fingers and toes often associated with pain [10, 11••, 18,19,20,21]. After morbilliform reactions, COVID-toes were the second most frequently noted cutaneous symptom with COVID-19 infection in dermatologic registries and case collections, reported in 18–19% of cases in the registry and case collection [11••, 13••]. The exact incidence of pernio/chilblains after COVID-19 is not known; however, large cohort studies from France and the UK note pernio/chilblains in 3.7% and acral rashes in 3.1% of patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2, respectively [6, 8]. This reaction tends to affect the young to middle-aged population with the median age in large studies ranging from 22 to 59 years [11••], and 17 to 38 years [20]. One study reported an average age range as young as 12 to 14 years [22]. The relationship between pernio/chilblains and SARS-CoV-2 remains controversial [23, 24]; these same large studies from France (28,957 patients in the Covidom study) and the UK (336,847 users of the COVID symptom study app) demonstrated an association between pernio/chilblains and having a positive test for SARS-CoV-2, with an OR of 1.74 (95% CI 1.33–2.28, p = 5.9 × 10−5) for positive versus negative swab test in the UK study [6]. The pathophysiology of COVID toes is thought to be related to a virus-induced type I interferonopathy [25, 26]. Statistically significant increases in interferon-α have been observed in COVID-19 patients with pernio/chilblains compared to COVID-19 without chilblains [25]. COVID toes are generally associated with milder or asymptomatic COVID-19; it is hypothesized that this is due to the far more robust interferon-α activation, leading to both mild COVID-19 and pernio/chilblains [22, 23].

Hair Loss

Hair loss associated with COVID-19 infection has been recorded in the forms of alopecia areata and telogen effluvium (TE). In the AAD/ILDS registry report, alopecia areata was only reported in one patient with no reports from the Spanish case collection study [11••, 13••]. A long-term study out of Wuhan, China followed 538 people who had COVID-19; 28.6% of this cohort reported some form of alopecia [27]. COVID-19 infection has been described as a stressor event leading to hair shedding in TE [28,29,30,31]. One study of 552 patients with laboratory-confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection described TE in nearly 2% of the patients [28]. Multiple cohort studies, case series, and case reports present cases of TE pattern hair loss 3 to 5 months after COVID-19 infection [31,32,33].

Urticaria

Of laboratory-confirmed cases of COVID-19 skin manifestations entered into skin registries and case collections, urticaria makes up 16–19% of the cases entered [11••, 13••]. The incidence of new-onset urticaria out of all patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 is unknown. This reaction generally presents as urticaria distributed on the trunk and sometimes the extremities; often with associated pruritus [34]. Both acute urticaria and chronic spontaneous urticaria (defined as waxing and waning pruritic wheals for greater than 6 weeks) have been reported after COVID-19 infection [35]. In a 140-patient retrospective study, 1.4% of patients had new-onset urticaria [36, 37]. Urticarial reactions have been associated with moderate to severe presentations of COVID-19 infection [11••].

Purpuric and Vasculitic Rashes

Palpable purpuric or vasculitic rashes after SARS-CoV-2 infection have been described as violaceous papules with possible ulceration predominantly effecting the lower limbs. These lesions occurred predominantly in patients with severe COVID-19 and represent between 3 and 8% of the cutaneous lesions after COVID-19 reported from the registry [11••]. On the other hand, retiform purpuric lesions, branching, non-blanching violaceous plaque or patch, are present in 6.4% of patients with COVID skin manifestations and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who were entered into the registry [11••]. Case reports and case series are scarce and predominantly report cases of leukocytoclastic vasculitis [38, 39]. Population-level incidence of vasculitis after COVID-19 is unknown.

Papulosquamous Eruptions

Papulosquamous eruptions were reported in 9.9% of individuals with COVID skin manifestations and laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 who were entered into the AAD/ILDS COVID registry; this reaction morphology was not reported in the large Spain nationwide case collection [11••, 13••]. Several different types of papulosquamous eruptions have been noted. One, noted to be thin scaly erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk often associated with pruritus, may resemble pityriasis rosea and has been called “pityriasis rosea-like” [40].

Psoriasis has also been noted to flare after SARS-CoV-2 infection [41, 42]. In some cases, the flare-up of disease in people with pre-existing psoriasis was attributed to either the discontinuation of immunosuppressive medications such as biologics due to concerns for COVID-19 infection or use of prednisone or hydroxychloroquine as treatments for COVID-19 [43].

Livedo Reticularis

Livedo reticularis has been described as reticular erythematous violaceous macules most often in the distribution of the lower extremities [44, 45]. This reaction has been reported in ~ 5% of registry cases [11••]. Livedo reticularis has been postulated to be a visible manifestation of the hypercoagulable state seen in patients with COVID-19, but has not been associated with clotting [46, 47]. While livedo reticularis is generally a bilateral condition, there are few cases reported of unilateral livedo reticularis after COVID-19 [48].

Vesicular Reactions

Vesicular rashes after COVID-19 were present in between 9% and 11% of all registry and case collection reported cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 infection [11••, 13••]. Vesicular reactions were described as small monomorphic vesicles at the same stage. These lesions differ from chickenpox, which often presents with vesicles at different stages of healing [49,50,51]. Some vesicular reactions are consistent with herpes zoster reactivation; however, many of these patients had otherwise immunocompromising co-morbidities [52].

Grover-Like

Grover-like reactions are described as transient, erythematous papules and papulo-vesicles. They account for less than 5% of overall skin reactions reported after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the registry-based studies. In one case that reported grover-like reaction in a COVID-19-positive patient, the condition resolved within a few weeks with no scarring [53].

Bullous Disease

Few cases of new-onset bullous disease during or after COVID-19 have been reported to date. In Freeman et al., new-onset bullous disease was reported in approximately 2% of patients reporting cutaneous manifestations in the registry [11••]. The bullae are described as tense, tender blisters on an erythematous scaly base [54, 55]. The majority of studies and articles focus on individuals with pre-existing bullous disease who had flares of their disease. For the few cases on new-onset bullous disease in patients with COVID-19, it is speculated that the viral infection could have simply unmasked underlying disease [54, 55].

Petechial Reactions

Petechial reactions, pinpoint red, brown, or purple non-blanching lesions, were reported in 3% of cutaneous reactions after laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 in Freeman et al. [11••]. Multiple cases of immune thrombocytopenia after COVID-19 presented with petechiae and concurrent purpura on the skin [56,57,58,59]. Very few cases of isolated petechial rashes associated with COVID-19 in patients with normal platelet counts have been reported to date [60].

Erythroderma

Erythroderma has rarely been noted with COVID-19 [11••]. Erythroderma is diffuse erythema and scaling involving a majority of the skin. While there were many case reports of flare-up in patients with previously diagnosed psoriatic or eczematous erythroderma, there is little literature on new-onset erythroderma in COVID-19-positive patients [61, 62].

Other

Erythema multiforme, SJS-TEN, and other severe cutaneous/mucocutaneous reactions on the SJS-TEN spectrum were very rarely reported in association with COVID-19, with just a few isolated case reports in the literature [63].

Pediatrics

Initial studies on COVID-19 in the pediatric population reported generally milder disease severity in otherwise healthy children when compared with adults [64]. As the pandemic evolved, a new hyperinflammatory condition, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), has presented in multiple centers across the USA, Europe, and Asia [64, 65]. MIS-C is a sequela to COVID-19 that presents with multi-organ involvement, most commonly gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, hematological, and mucocutaneous. The cutaneous clinical findings include acro-ischemia, bullae, dry gangrene, and maculopapular rash. In a prospective study on MIS-C from Israel, the Alpha and Delta variants of COVID-19 had higher incidences per 100,000 people under the age of 18 than Omicron (54.5 during Alpha, 49.2 during Delta, and 3.8 during Omicron) [65]. A nationwide prospective study from Denmark notes incidence to be 246 per 1,000,000 people between the ages of 0 and 17 [66].

Long COVID

Long COVID, also known as post-acute sequelae of COVID, is defined as the illness that occurs in people who have a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection; usually within 3 months from the onset of COVID-19, with symptoms and effects that last for at least 2 months [67]. Long COVID can occur in the skin, in the form of pernio/chilblains, urticaria, or papulosquamous eruptions, livedo reticularis, and others [68]. In one study, 6.8% of the 103 registry cases of pernio/chilblains lasted longer than 60 days [68, 69].

Skin of Color

Much of the literature and imaging available today surrounding COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestation is on lighter skin, with little representation of skin of color [70, 71]. This is despite the fact that individuals with skin of color are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 [72, 73]. Early in the pandemic, Lester et al. reported that of publications on COVID-19 and dermatology, 91% of images involved white patients and 9% were Hispanic, with no representation of cutaneous manifestations in dark skin [74]. This gap needs to be addressed to facilitate clinicians to more effectively identify and treat COVID-19 associated cutaneous findings in people with skin of color.

Cutaneous Reactions to COVID-19 Vaccines

Starting December 2, 2020, the first COVID vaccine was approved for emergency use authorization in the UK, quickly followed by the USA, Canada, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain [75]. Cutaneous reactions were initially noted in the vaccine clinical trials [76, 77], and quickly thereafter were noted in case series [78], registries [79••], and reports from around the globe (Table 2) [80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93, 94••]. The most frequently reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccines were delayed large local reactions, followed by local injection site reactions, urticarial eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions [79••]. Similar morphologies of reactions occur after booster doses, although it is possible to develop a reaction to a booster dose without having reacted to the original vaccine series [95, 96]. Yet, it is essential to note that cutaneous reactions to COVID-19 vaccines are actually less frequent over time and with subsequent doses and should not preclude one from obtaining additional booster doses as and when they become available [96, 97].

Local Injection Site Reactions and Delayed Large Local Reactions

Local injection site reactions to the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Comirnaty (Pfizer/BioNTech; BNT162b2), Moderna (Moderna; mRNA‐1273)) were identified in initial clinical trials [76, 77]. Local injection site reactions have also been noted after administration of Vaxzevira (AstraZeneca; AZD1222), Janssen COVID‐19 vaccine (Johnson & Johnson; Ad26.COV2.S), Convidecia (CanSino Biologics), Sputnik V (Gamaleya Research Institute), and CoronaVac (Sinovac) [98]. These reactions have been categorized as swelling, erythema, and pain at the site of injection within 3 days of vaccination [79••].

Localized Swelling, Erythema, and Pain within 3 Days of Vaccination

Local injection site reactions were reported in between 15% (erythema and swelling) and 88% (pain) of patients in the original clinical trials for Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, JNJ, Gam-COVID-Vac, and CoronaVac [80]. They were also frequently reported in registries and cross-sectional nationwide studies, representing between 20 and 30% of all reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination [79••, 94••]. They occur within 3 days of vaccine administration and are generally self-limited, and resolve quickly without interventions [79••, 94••].

Delayed Local Hypersensitivity Reaction

In addition, the novel phenomenon of delayed large local reactions, colloquially known as COVID-arm, have been reported specifically after mRNA COVID-19 vaccines [78, 95]. These reactions, described as erythematous patches or swollen plaque at the injection site, usually develop 7 to 8 days following injection and no later than 21 days post-vaccination [15, 78, 99]. The reaction lasts 2 to 11 days after onset, and generally will self-resolve or can be managed symptomatically with ice and antihistamines [78]. On rare occasions, there have been isolated reports of nodular and vesicular pruritic local reactions at the site of vaccination [100, 101].

Delayed large local reactions were reported most commonly after doses of the Moderna mRNA‐1273 vaccine, but were also noted, although less commonly, with the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine [78, 95, 102].

Generalized Reactions

The generalized or distal reaction pattern is used to described reactions in locations non-adjacent to or at the vaccine injection site. These reactions are composed of morbilliform, urticaria, V-REPP, bullous disease, hair loss, vasculitis, and vitiligo [79••, 94••]. In this section, we will discuss the most frequently reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination.

Morbilliform Eruption

One of the most common generalized post-vaccine cutaneous reactions, morbilliform eruptions, is defined as erythematous, maculopapular rashes reminiscent of measles, mostly generalized affecting the trunk and limbs [94••]. Of all skin reactions after COVID-19 vaccination reported in registries and large case series, morbilliform eruptions account for 6 to 9% of skin reactions recorded [79••, 94••]. They tend to appear about 4 days after vaccination and last an average of 10 days [94••]. They have been reported after the primary vaccine series, and also after booster doses [96].

Urticaria

Urticaria can appear immediately (defined as < 4 h after vaccination by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)) as part of anaphylaxis to a COVID-19 vaccine. Anaphylaxis after COVID-19 vaccines is rare, reported at a rate of 11.1 per million doses of Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 vaccine [103]. More commonly, urticaria is delayed in onset, > 4 h to several days (1 to 8 days) after vaccination, with most appearing about 5 days post-vaccination [94••]. Urticaria starting after 4 h is not an indication of an anaphylactic reaction to the vaccine.

Between 11 and 15% of registry-reported cutaneous reactions are urticarial in nature [79••, 94••]. While most urticaria post-vaccine resolve within 1 to 2 weeks [94••, 104], urticaria may last > 6 weeks, known as chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU). This phenomenon has been noted after the initial vaccine series and also after booster doses [96]. In CSU cases, omalizumab has been used as a treatment option [104, 105].

Herpes Zoster Reactivation/Shingles

Herpes zoster may be triggered by COVID-19 vaccination, although there is debate in the infectious disease literature regarding the strength of this association; a causal association between herpes zoster reactivation and COVID-19 vaccination requires additional data [106,107,108,109]. In addition, the larger registry and cross-sectional studies report that herpes zoster reactivation accounts for up to 13% of total reactions [79••, 92, 94••]. These cases presented classically as clustered vesicles on an erythematous base in a dermatomal pattern [108].

Pernio/Chilblains

Pernio/chilblains has also been reported to flare after COVID-19 vaccination [110]. This phenomenon can occur de novo, but also in patients who had pernio/chilblains after COVID itself and then re-flared after vaccination. Of all cutaneous reactions post-vaccination in registries and case series, pernio accounted for 0.5 to 3% [79••, 92, 94••]. While the mechanism is not yet known, this presentation may be a result of interferon-alpha or other immune response to the vaccine similar to that seen after SARS-CoV-2 infection itself [110].

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme was reported in less than 1% of cases [79••, 92, 94••]. Erythema multiforme (EM) has been associated with triggers such as viruses and vaccines in the past, yet there are very few reports to date of EM after COVID-19 vaccination [111, 112]. These lesions are described as “predominantly acral, targetoid papules, made up of three concentric distinct zones” [111].

Bullous Disease

While bullous disease accounted for less than 1% of cases in the large registry and cross-sectional studies, several case reports and case series have identified subepidermal blistering eruptions after COVID-19 vaccination [79••, 92, 94••, 113,114,115,116]. In a case series of 12 cases in patients aged 42 to 97 years, bullous disease was noted after first vaccination with recurrence in one patient with second vaccination [97]. All patients recovered. The authors hypothesize that some cases, especially in older individuals, may represent unmasking of pre-existing pre-bullous bullous pemphigoid, while other cases, particularly in the younger population, where the eruption was self-limited and of short duration, may be truly new events triggered by the vaccine [97]. All 12 cases in this study were recorded after an mRNA vaccine, and in some cases may have unmasked pre-bullous bullous pemphigoid, while in others may have been associated with new onset [97]. The association between bullous disease and COVID-19 vaccines needs further elucidation [97]. Authors conclude that bullous eruption after COVID-19 vaccination should not preclude further vaccination or boosters [97].

Hair Loss

Several types of hair loss have been reported after COVID-19 vaccination, including alopecia areata and telogen effluvium [117,118,119,120,121]. Alopecia areata has been noted either with rapid onset after vaccination or recurrences of alopecia areata after COVID-19 vaccination [117,118,119,120,121,122]. The association between vaccination and alopecia can be particularly difficult to establish, given the time lag between vaccination and the onset of hair loss [117,118,119,, 120].

V-REPP (Vaccine-Related Eruption of Papules and Plaque)

Vaccine-related eruption of papules and plaques (V-REPP) is a spectrum of vaccine reactions defined based on histopathologic pattern more than clinical morphology. In a study of 58 histopathology reports over 13 different reactions patterns, the AAD/ILDS COVID-19 Dermatology registry team characterized V-REPP as histopathologic spectrum of spongiotic (robust) to interface dermatitis (mild) [14].

Robust V-REPP was characterized on histopathology as a spongiotic process, which clinically manifests as a vesicular or papulo-vesicular eruption [14, 79••, 92, 94••]. These reactions accounted for over 5% of registry reported cutaneous reactions after COVID-19 vaccination. One case was reported of a patient with scattered vesicles over the lower extremities developing this rash after two doses of the Pfizer vaccine [123]. Moderate V-REPP was characterized as a combination of spongiosis and interface change, and clinically appears more consistent with pityriasis-rosea like lesions, which are often oval in nature and can follow a protracted course. Described as erythematous, scaly oval-shaped plaques in a “Christmas tree” distribution on the trunk, this reaction was fairly uncommon and seen in less than 5% of registry reported reactions [79••, 92, 94••, 124, 125]. Finally, mild V-REPP is an interface dermatitis, which clinically can mimic an eczematous dermatitis [14].

Psoriasis Flare

Psoriasis flares have been scarcely reported after COVID-19 vaccines in the literature, which consist of case reports, case series, registry studies, cross sectional, and cohort studies [79••, 126,127,128,129]. It has been hypothesized that both adenovirus-vector and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines may act as a trigger for psoriatic flares; however, further investigation and large controlled studies are necessary to understand the relationship [127].

Vasculitic Reactions/Purpuric Rash

Vasculitis and/or palpable purpura have also been noted after COVID vaccination [79••, 92, 94••], some with biopsy-confirmed vasculitis [130, 131]. Vasculitis subtypes noted in the literature have included leukocytoclastic vasculitis and urticarial vasculitis [132,133,134,135,136,137,138].

Vitiligo

Vitiligo has only been reported in a handful of cases after COVID-19 vaccination and was not explicitly documented in the large registry-based studies [139,140,141,142,143,144]. At least one case noted new-onset depigmentation specifically over the site of vaccination [145].

Filler Reaction

Dermal filler reactions were noted early on in the vaccine roll-out both in vaccine trials (Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 and Moderna mRNA‐1273) [76, 77] and in the lay press [146, 147]. Case reports ranged from nodular reactions to angioedema in areas where patients had previously received dermal filler, presenting 3 to 8 days after COVID-19 vaccination [148,149,150,151,152]. Patients who developed these reactions had filler ranging from 2 weeks to 2 years prior to their vaccination [149]. One hypothesized mechanism for this reaction was activation of ACE pathway, and ACE inhibitors have been proposed as a possible treatment mechanism [149, 150].

Other

Pyoderma gangrenosum [153,154,155], erythema nodosum [156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163], and SJS/TEN [164, 165] all have very few isolated cases reported after COVID-19 vaccination. For many reactions with only a handful of reported cases after COVID-19 vaccination, correlation between the vaccine and the skin condition has yet to be established.

Pediatric

MIS-C after COVID-19 vaccination has been rarely reported in the literature. One study identified the incidence of MIS-C after COVID-19 vaccination to be 1 case per 1,000,000 doses of the vaccine in individuals 12 to 20 years old [166].

Discussion

With over 6 million deaths since the start of the pandemic and only 60.89% of the world fully vaccinated (not boosted) as of June 2022, the first 2 years of the pandemic have seen significant changes in all realms of healthcare, with continued evolution with new variants and vaccines [1, 167, 168].

The pandemic has highlighted the underlying structural racism and healthcare disparities that exist within healthcare systems. COVID-19 has unevenly affected black, Hispanic, native American, and immigrant communities, who continue to bear the heaviest burden of disease [169, 170]. In the USA, black individuals account for the majority of COVID-19 death rates (2 to 2.5 times the rate in white and Asian populations) in multiple states [171]. At the start of the pandemic, 97.9 out of every 100,000 black individuals died from COVID-19 compared to 46.6 per 100,000 for white individuals and 40.4 per 100,000 for Asians [172].

Vaccine equity is a major challenge of our times. As of June 1, 2022, 19.4% of individuals in low-income countries have received one dose of the vaccine compared to 78.4% in high income countries [1]. While global collaborations such as COVAX exist, with the aim of providing access to COVID-19 vaccines to people globally and functioning as a mechanism through which governments and key stakeholders worked together to get the pandemic under control [173], this has not sufficiently addressed the gap in vaccine distribution and access worldwide [1]. This remains clinically relevant to all fields of medicine as the reactions to COVID-19 vaccines that are being reported may not be appropriately representative of the worldwide population.

It is important to also acknowledge the international collaboration that has arisen in the face of the pandemic, across all of medicine and in dermatology in particular. One example of this is the collaboration between COVID-19 dermatology registries [174, 175].

Despite these new international collaborations, a major challenge still lies in communicating this information to clinicians given the relatively weak to non-existent evidence base for many reported associations which predominantly arise from case reports of common conditions in the setting of billions of vaccine exposures. Unfortunately, case reports and case series can only provide a hypothesis of an association, and need to be further investigated with controlled studies. Many of the reported studies in this review are in fact based on spontaneous reports including registries, nationwide reports, case studies, and case series.

SARS-CoV-2 Infection and the Skin

Cutaneous reactions to the SARS-CoV-2 infection may be the presenting sign of infection and can also give clues into how a patient’s immune system is responding to the virus. Our understanding continues to evolve, even as the virus itself is changing. We may come to consider COVID-19 to be “the great mimicker or imitator” in the skin, previously a term used for syphilis [176], given its propensity to lead to over > 30 different skin eruptions. In this review, we have outlined the most common cutaneous reactions in COVID-19-positive patients to date; however, the evolution in cutaneous findings with newer variants is an area of active investigation [177••].

COVID-19 Vaccine and the Skin

Like the virus itself, COVID-19 vaccines have also led to a wide array of skin reactions and manifestations, reviewed here. However, the majority of reactions noted after COVID-19 vaccination are self-limited and non-life threatening, and do not preclude an individuals from obtaining additional COVID-19 booster vaccines or other vaccinations. In addition, as the mRNA platform is used for other vaccines in the future, we may find knowledge gained from evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine skin reactions to be useful with other diseases and other vaccination campaigns.

One challenge in evaluating cutaneous manifestations following COVID-19 vaccination is evaluating association and causation. Many conditions seen after COVID-19 vaccination such as alopecia or herpes zoster reactivation are common and understanding whether incidence of these conditions truly increases after vaccination will take large, population-based studies. Based on CDC and allergy guidance, our group has proposed a time cut-off of 21 days post-vaccine for consideration of whether a skin eruption may be evaluated for possible association with a vaccination, but this is an active area of debate and investigation [15].

Conclusion

With new COVID-19 variants and vaccines, our knowledge of how the skin responds to SARS-CoV-2 continues to evolve. Dermatologists have an important role both in evaluating skin manifestations of the virus, but also in discussing and recommending COVID-19 vaccines to their patients. As a specialty, we have an important role to play in pandemic response.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). 2020. Accessed 27 Apr 2022.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30183-5.

Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7.

Organization WHO. WHO COVID-19 Case definition. 2022.

Menni C, Valdes AM, Polidori L, Antonelli M, Penamakuri S, Nogal A, et al. Symptom prevalence, duration, and risk of hospital admission in individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 during periods of omicron and delta variant dominance: a prospective observational study from the ZOE COVID Study. The Lancet. 2022;399(10335):1618–24.

Visconti A, Bataille V, Rossi N, Kluk J, Murphy R, Puig S, et al. Diagnostic value of cutaneous manifestation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(5):880–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19807.

Le Cleach L. Dermatology and COVID-19: much knowledge to date but still a lot to discover. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2021;148(2):69–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annder.2021.03.001.

Mascitti H, Jourdain P, Bleibtreu A, Jaulmes L, Dechartres A, Lescure X, et al. Prognosis of rash and chilblain-like lesions among outpatients with COVID-19: a large cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(10):2243–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-021-04305-3.

De Giorgi V, Recalcati S, Jia Z, Chong W, Ding R, Deng Y, et al. Cutaneous manifestations related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a prospective study from China and Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):674–5.

Kolivras A, Thompson C, Pastushenko I, Mathieu M, Bruderer P, de Vicq M, et al. A clinicopathological description of COVID-19-induced chilblains (COVID-toes) correlated with a published literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14099.

••Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, Rosenbach M, Kovarik C, Desai SR, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1118–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016. This reference is considered important as it is one of the largest studies or registries that report significant data on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccine related cutaneous reactions.

Freeman EE, Chamberlin GC, McMahon DE, Hruza GJ, Wall D, Meah N, et al. Dermatology COVID-19 registries: updates and future directions. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(4):575–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2021.05.013.

••Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Fernández-Nieto D, Rodríguez-Villa Lario A, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(1):71–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19163. This reference is considered important as it is one of the largest studies or registries that report significant data on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccine related cutaneous reactions.

McMahon DE, Kovarik CL, Damsky W, Rosenbach M, Lipoff JB, Tyagi A, et al. Clinical and pathologic correlation of cutaneous COVID-19 vaccine reactions including V-REPP: a registry-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.002.

Singh R, Ali R, Prasad S, Chen ST, Blumenthal K, Freeman EE. Proposing a standardized assessment of COVID-19 vaccine-associated cutaneous reactions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2022.05.011.

Alonso MN, Mata-Forte T, García-León N, Vullo PA, Ramirez-Olivencia G, Estébanez M, et al. Incidence, characteristics, laboratory findings and outcomes in acro-ischemia in COVID-19 patients. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2020;16:467–78. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.S276530.

Gawaz A, Guenova E. Microvascular skin manifestations caused by COVID-19. Hamostaseologie. 2021;41(5):387–96. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1581-6899.

Andina D, Noguera-Morel L, Bascuas-Arribas M, Gaitero-Tristán J, Alonso-Cadenas JA, Escalada-Pellitero S, et al. Chilblains in children in the setting of COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(3):406–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14215.

Colmenero I, Santonja C, Alonso-Riaño M, Noguera-Morel L, Hernández-Martín A, Andina D, et al. SARS-CoV-2 endothelial infection causes COVID-19 chilblains: histopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of seven paediatric cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):729–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19327.

Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, Rosenbach M, Kovarik C, Takeshita J, et al. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):486–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109.

Sachdeva M, Mufti A, Maliyar K, Lara-Corrales I, Salcido R, Sibbald C. A review of COVID-19 chilblains-like lesions and their differential diagnoses. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34(7):348–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.Asw.0000752692.72055.74.

Ladha MA, Luca N, Constantinescu C, Naert K, Ramien ML. Approach to chilblains during the COVID-19 pandemic [Formula: see text]. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(5):504–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1203475420937978.

Sun Q, Freeman EE. Chilblains and COVID-19-an update on the complexities of interpreting antibody test results, the role of interferon α, and COVID-19 vaccines. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(2):217–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5172.

Gehlhausen JR, Little AJ, Ko CJ, Emmenegger M, Lucas C, Wong P, et al. Lack of association between pandemic chilblains and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(9). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2122090119.

Hubiche T, Cardot-Leccia N, Le Duff F, Seitz-Polski B, Giordana P, Chiaverini C, et al. Clinical, laboratory, and interferon-alpha response characteristics of patients with chilblain-like lesions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(2):202–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4324.

Magro CM, Mulvey JJ, Laurence J, Sanders S, Crowson AN, Grossman M, et al. The differing pathophysiologies that underlie COVID-19-associated perniosis and thrombotic retiform purpura: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(1):141–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19415.

Xiong Q, Xu M, Li J, Liu Y, Zhang J, Xu Y, et al. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: a single-centre longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27(1):89–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.023.

Olds H, Liu J, Luk K, Lim HW, Ozog D, Rambhatla PV. Telogen effluvium associated with COVID-19 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2): e14761. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14761.

Sharquie KE, Jabbar RI. COVID-19 infection is a major cause of acute telogen effluvium. Ir J Med Sci. 2021:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02754-5.

Aksoy H, Yıldırım UM, Ergen P, Gürel MS. COVID-19 induced telogen effluvium. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15175. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15175.

Gruenstein D, O'Mara M, Pa SH, Levitt J, Pa SL, Tom J, et al. Telogen effluvium caused by COVID-19 in Elmhurst, New York: report of a cohort and review. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(10). https://doi.org/10.5070/d3271055619.

Mieczkowska K, Deutsch A, Borok J, Guzman AK, Fruchter R, Patel P, et al. Telogen effluvium: a sequela of COVID-19. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(1):122–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15313.

Moreno-Arrones OM, Lobato-Berezo A, Gomez-Zubiaur A, Arias-Santiago S, Saceda-Corralo D, Bernardez-Guerra C, et al. SARS-CoV-2-induced telogen effluvium: a multicentric study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(3):e181–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17045.

Algaadi SA. Urticaria and COVID-19: a review. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e14290. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14290.

Najafzadeh M, Shahzad F, Ghaderi N, Ansari K, Jacob B, Wright A. Urticaria (angioedema) and COVID-19 infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):e568–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16721.

Kaushik A, Parsad D, Kumaran MS. Urticaria in the times of COVID-19. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e13817. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.13817.

Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, Yuan YD, Yang YB, Yan YQ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan. China Allergy. 2020;75(7):1730–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.14238.

Kumar G, Pillai S, Norwick P, Bukulmez H. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis secondary to COVID-19 infection in a young child. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-242192.

Alattar KO, Subhi FN, Saif Alshamsi AH, Eisa N, Shaikh NA, Mobushar JA, et al. COVID-19-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis leading to gangrene and amputation. IDCases. 2021;24: e01117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01117.

Sanchez A, Sohier P, Benghanem S, L’Honneur AS, Rozenberg F, Dupin N, et al. Digitate papulosquamous eruption associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(7):819–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1704.

Miladi R, Janbakhsh A, Babazadeh A, Aryanian Z, Ebrahimpour S, Barary M, et al. Pustular psoriasis flare-up in a patient with COVID-19. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(11):3364–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14508.

Nasiri S, Araghi F, Tabary M, Gheisari M, Mahboubi-Fooladi Z, Dadkhahfar S. A challenging case of psoriasis flare-up after COVID-19 infection. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(5):448–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1764904.

Aram K, Patil A, Goldust M, Rajabi F. COVID-19 and exacerbation of dermatological diseases: a review of the available literature. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15113. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15113.

Manalo IF, Smith MK, Cheeley J, Jacobs R. A dermatologic manifestation of COVID-19: transient livedo reticularis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.018.

Tusheva I, Damevska K, Dimitrovska I, Markovska Z, Malinovska-Nikolovska L. Unilateral livedo reticularis in a COVID-19 patient: case with fatal outcome. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;7:120–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.10.033.

Sahara T, Yokota K. Livedo reticularis associated with COVID-19. Intern Med. 2022;61(3):441. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.8033-21.

Khalil S, Hinds BR, Manalo IF, Vargas IM, Mallela S, Jacobs R. Livedo reticularis as a presenting sign of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(9):871–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.07.014.

Rahimi H, Tehranchinia Z. A comprehensive review of cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1236520. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1236520.

Palaniappan V, Subramaniam K, Karthikeyan K. Papular-vesicular rash in COVID-19. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(3):551–2. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.21-0578.

Mahé A, Birckel E, Merklen C, Lefèbvre P, Hannedouche C, Jost M, et al. Histology of skin lesions establishes that the vesicular rash associated with COVID-19 is not “varicella-like.” J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(10):e559–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16706.

Tatu AL, Baroiu L, Fotea S, Anghel L, Drima Polea E, Nadasdy T, et al. A working hypothesis on vesicular lesions related to COVID-19 infection, Koebner phenomena type V, and a short review of related data. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:419–23. https://doi.org/10.2147/ccid.S307846.

Tartari F, Spadotto A, Zengarini C, Zanoni R, Guglielmo A, Adorno A, et al. Herpes zoster in COVID-19-positive patients. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(8):1028–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15001.

Boix-Vilanova J, Gracia-Darder I, Saus C, Ramos D, Llull A, Santonja C, et al. Grover-like skin eruption: another cutaneous manifestation in a COVID-19 patient. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(10):1290–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15104.

Olson N, Eckhardt D, Delano A. New-onset bullous pemphigoid in a COVID-19 patient. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2021;2021:5575111. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5575111.

Goon PKC, Bello O, Adamczyk LA, Chan JYH, Sudhoff H, Banfield CC. Covid-19 dermatoses: acral vesicular pattern evolving into bullous pemphigoid. Skin Health Dis. 2021;1(1): e6. https://doi.org/10.1002/ski2.6.

Bomhof G, Mutsaers P, Leebeek FWG, Te Boekhorst PAW, Hofland J, Croles FN, et al. COVID-19-associated immune thrombocytopenia. Br J Haematol. 2020;190(2):e61–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.16850.

Tarawneh O, Tarawneh H. Immune thrombocytopenia in a 22-year-old post Covid-19 vaccine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):E133–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.26106.

Murt A, Eskazan AE, Yılmaz U, Ozkan T, Ar MC. COVID-19 presenting with immune thrombocytopenia: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Virol. 2021;93(1):43–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26138.

Bhattacharjee S, Banerjee M. Immune thrombocytopenia secondary to COVID-19: a systematic review. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(11):2048–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00521-8.

Diaz-Guimaraens B, Dominguez-Santas M, Suarez-Valle A, Pindado-Ortega C, Selda-Enriquez G, Bea-Ardebol S, et al. Petechial skin rash associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(7):820–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1741.

Ghalamkarpour F, Pourani MR, Abdollahimajd F, Zargari O. A case of severe psoriatic erythroderma with COVID-19. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(2):1111–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546634.2020.1799918.

Iwasawa O, Kamiya K, Okada H, Komine M, Ohtsuki M. A case of erythroderma with elevated serum immunoglobulin E and thymus and activation-regulated chemokine levels following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination. J Dermatol. 2022;49(3):e117–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.16257.

Mashayekhi F, Seirafianpour F, Pour Mohammad A, Goodarzi A. Severe and life-threatening COVID-19-related mucocutaneous eruptions: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(12): e14720. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14720.

Kabeerdoss J, Pilania RK, Karkhele R, Kumar TS, Danda D, Singh S. Severe COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, and Kawasaki disease: immunological mechanisms, clinical manifestations and management. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-020-04749-4.

Levy N, Koppel JH, Kaplan O, Yechiam H, Shahar-Nissan K, Cohen NK, et al. Severity and incidence of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during 3 SARS-CoV-2 pandemic waves in Israel. JAMA. 2022;327(24):2452–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.8025.

Nygaard U, Holm M, Hartling UB, Glenthøj J, Schmidt LS, Nordly SB, et al. Incidence and clinical phenotype of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children after infection with the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant by vaccination status: a Danish nationwide prospective cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(7):459–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(22)00100-6.

WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): post COVID-19 condition. 2021.

McMahon DE, Gallman AE, Hruza GJ, Rosenbach M, Lipoff JB, Desai SR, et al. Long COVID in the skin: a registry analysis of COVID-19 dermatological duration. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):313–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30986-5.

Tammaro A, Parisella FR, Adebanjo GAR. Cutaneous long COVID. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(8):2378–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14291.

Daneshjou R, Rana J, Dickman M, Yost JM, Chiou A, Ko J. Pernio-like eruption associated with COVID-19 in skin of color. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6(9):892–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2020.07.009.

Kluger N, Samimi M. Is there an under-representation of skin of colour images during the COVID-19 outbreak? Med Hypotheses. 2020;144: 110270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2020.110270.

Goyal S, Prabhu S, U S, Pai SB, Mohammed A. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19 in skin of color: a firsthand perspective of three cases in a tertiary care center in India. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(3):307–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2020.1852784.

Akuffo-Addo E, Nicholas MN, Joseph M. COVID-19 skin manifestations in skin of colour. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;26(2):189–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/12034754211053310.

Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, Okoye GA, Linos E. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(3):593–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19258.

Lamb YN. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: first approval. Drugs. 2021;81(4):495–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-021-01480-7.

Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2035389.

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–15. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2034577.

Blumenthal KG, Freeman EE, Saff RR, Robinson LB, Wolfson AR, Foreman RK, et al. Delayed large local reactions to mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(13):1273–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2102131.

••McMahon DE, Amerson E, Rosenbach M, Lipoff JB, Moustafa D, Tyagi A, et al. Cutaneous reactions reported after Moderna and Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination: a registry-based study of 414 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.092. This reference is considered important as it is one of the largest studies or registries that report significant data on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccine related cutaneous reactions.

Sun Q, Fathy R, McMahon DE, Freeman EE. COVID-19 vaccines and the skin: the landscape of cutaneous vaccine reactions worldwide. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(4):653–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.det.2021.05.016.

Corbeddu M, Diociaiuti A, Vinci MR, Santoro A, Camisa V, Zaffina S, et al. Transient cutaneous manifestations after administration of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine: an Italian single-centre case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(8):e483–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17268.

Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, Girolomoni G. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10225344.

Tihy M, Menzinger S, André R, Laffitte E, Toutous-Trellu L, Kaya G. Clinicopathological features of cutaneous reactions after mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(12):2456–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17633.

Grieco T, Maddalena P, Sernicola A, Muharremi R, Basili S, Alvaro D, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions after COVID-19 vaccines in a cohort of 2740 Italian subjects: an observational study. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15153. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15153.

Avallone G, Quaglino P, Cavallo F, Roccuzzo G, Ribero S, Zalaudek I, et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccine-related cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.16063.

Oliva Rodríguez-Pastor S, Martín Pedraz L, Carazo Gallego B, Galindo Zavala R, Lozano Sánchez G, de Toro PI, et al. Skin manifestations during the COVID-19 pandemic in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Int. 2021;63(9):1033–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.14568.

Magro C, Nuovo G, Mulvey JJ, Laurence J, Harp J, Crowson AN. The skin as a critical window in unveiling the pathophysiologic principles of COVID-19. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39(6):934–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.07.001.

Hoff NP, Freise NF, Schmidt AG, Firouzi-Memarpuri P, Reifenberger J, Luedde T, et al. Delayed skin reaction after mRNA-1273 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a rare clinical reaction. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):98. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-021-00557-z.

Gambichler T, Boms S, Susok L, Dickel H, Finis C, Abu Rached N, et al. Cutaneous findings following COVID-19 vaccination: review of world literature and own experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(2):172–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17744.

Alpalhão M, Maia-Silva J, Filipe P. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccines and cutaneous adverse reactions: a review. Dermatitis. 2021;32(3):133–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/der.0000000000000755.

Kitagawa H, Kaiki Y, Sugiyama A, Nagashima S, Kurisu A, Nomura T, et al. Adverse reactions to the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2021.12.034.

Freeman EE, Sun Q, McMahon DE, Singh R, Fathy R, Tyagi A, et al. Skin reactions to COVID-19 vaccines: an American Academy of Dermatology/International League of Dermatological Societies registry update on reaction location and COVID vaccine type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.016.

Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Berti E, Marzano AV. Skin manifestations associated with COVID-19: current knowledge and future perspectives. Dermatology. 2021;237(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512932.

••Català A, Muñoz-Santos C, Galván-Casas C, Roncero Riesco M, Revilla Nebreda D, Solá-Truyols A, et al. Cutaneous reactions after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: a cross-sectional Spanish nationwide study of 405 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20639. This reference is considered important as it is one of the largest studies or registries that report significant data on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccine related cutaneous reactions.

Blumenthal KG, Ahola C, Anvari S, Samarakoon U, Freeman EE. Delayed large local reactions to Moderna COVID-19 vaccine: a follow-up report after booster vaccination. JAAD Int. 2022;8:3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2022.03.017.

Prasad S, McMahon DE, Tyagi A, Ali R, Singh R, Rosenbach M, et al. Cutaneous reactions following booster dose administration of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine: a first look from the American Academy of Dermatology/International League of Dermatologic Societies registry. JAAD Int. 2022;8:49–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdin.2022.04.004.

Tomayko MM, Damsky W, Fathy R, McMahon DE, Turner N, Valentin MN, et al. Subepidermal blistering eruptions, including bullous pemphigoid, following COVID-19 vaccination. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;148(3):750–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2021.06.026.

Kaur RJ, Dutta S, Bhardwaj P, Charan J, Dhingra S, Mitra P, et al. Adverse events reported from COVID-19 vaccine trials: a systematic review. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2021;36(4):427–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12291-021-00968-z.

Blumenthal KG, Phadke NA, Bates DW. Safety surveillance of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines through the vaccine safety datalink. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1375–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14808.

Edriss M, Farshchian M, Daveluy S. Localized cutaneous reaction to an mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(8):2380–1. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14288.

Tammaro A, Adebanjo GAR, Magri F, Parisella FR, Chello C, De Marco G. Local skin reaction to the AZD1222 vaccine in a patient who survived COVID-19. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(7):1965–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14205.

Samarakoon U, Alvarez-Arango S, Blumenthal KG. Delayed large local reactions to mRNA Covid-19 vaccines in blacks, indigenous persons, and people of color. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(7):662–4. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2108620.

Banerji A, Wickner PG, Saff R, Stone CA Jr, Robinson LB, Long AA, et al. mRNA vaccines to prevent COVID-19 disease and reported allergic reactions: current evidence and suggested approach. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1423–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.047.

Thomas J, Thomas G, Chatim A, Shukla P, Mardiney M. Chronic spontaneous urticaria after COVID-19 vaccine. Cureus. 2021;13(9): e18102. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18102.

Strahan A, Ali R, Freeman EE. Chronic spontaneous urticaria after COVID-19 primary vaccine series and boosters. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;25:63–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.05.012.

van Dam CS, Lede I, Schaar J, Al-Dulaimy M, Rösken R, Smits M. Herpes zoster after COVID vaccination. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;111:169–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.048.

Maranini B, Ciancio G, Cultrera R, Govoni M. Herpes zoster infection following mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Reumatismo. 2021;73(3). https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2021.1445.

Arora P, Sardana K, Mathachan SR, Malhotra P. Herpes zoster after inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a cutaneous adverse effect of the vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(11):3389–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14268.

Algaadi SA. Herpes zoster and COVID-19 infection: a coincidence or a causal relationship? Infection. 2022;50(2):289–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01714-6.

Lopez S, Vakharia P, Vandergriff T, Freeman EE, Vasquez R. Pernio after COVID-19 vaccination. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(2):445–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.20404.

Buján Bonino C, Moreiras Arias N, López-Pardo Rico M, Pita da Veiga Seijo G, Rosón López E, Suárez Peñaranda JM et al. Atypical erythema multiforme related to BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) COVID-19 vaccine. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(11):e466-e7. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15894.

Karatas E, Nazim A, Patel P, Vaidya T, Drew GS, Amin SA, et al. Erythema multiforme reactions after Pfizer/BioNTech (BNT162b2) and Moderna (mRNA-1273) COVID-19 vaccination: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.12.002.

Kong J, Cuevas-Castillo F, Nassar M, Lei CM, Idrees Z, Fix WC, et al. Bullous drug eruption after second dose of mRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 vaccine: case report. J Infect Public Health. 2021;14(10):1392–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.06.021.

Damiani G, Pacifico A, Pelloni F, Iorizzo M. The first dose of COVID-19 vaccine may trigger pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid flares: is the second dose therefore contraindicated? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(10):e645–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17472.

D’Cruz A, Parker H, Saha M. A bullous eruption following the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(12):e864–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17606.

Zhang Y, Lang X, Guo S, He H, Cui H. Bullous pemphigoid after inactivated COVID-19 vaccination: case report. Dermatol Ther. 2022:e15595. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15595.

Gallo G, Mastorino L, Tonella L, Ribero S, Quaglino P. Alopecia areata after COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Exp Vaccine Res. 2022;11(1):129–32. https://doi.org/10.7774/cevr.2022.11.1.129.

Essam R, Ehab R, Al-Razzaz R, Khater MW, Moustafa EA. Alopecia areata after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (Oxford/AstraZeneca): a potential triggering factor? J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(12):3727–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14459.

May Lee M, Bertolani M, Pierobon E, Lotti T, Feliciani C, Satolli F. Alopecia areata following COVID-19 vaccination: vaccine-induced autoimmunity? Int J Dermatol. 2022;61(5):634–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.16113.

Scollan ME, Breneman A, Kinariwalla N, Soliman Y, Youssef S, Bordone LA, et al. Alopecia areata after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;20:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.11.023.

Aryanian Z, Balighi K, Hatami P, Afshar ZM, Mohandesi NA. The role of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its vaccines in various types of hair loss. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(6): e15433. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15433.

Rossi A, Magri F, Michelini S, Caro G, Di Fraia M, Fortuna MC, et al. Recurrence of alopecia areata after covid-19 vaccination: a report of three cases in Italy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(12):3753–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14581.

MR AR, Syed Mohamad SN, Suria A, Shahra R. Vesicular rash following immunisation with BTN162b2 messenger RNA (mRNA) COVID-19 vaccine: vaccine related or coincidence? Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22133. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22133.

Cohen OG, Clark AK, Milbar H, Tarlow M. Pityriasis rosea after administration of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(11):4097–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2021.1963173.

Pedrazini MC, da Silva MH. Pityriasis rosea-like cutaneous eruption as a possible dermatological manifestation after Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine: case report and brief literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15129. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15129.

Krajewski PK, Matusiak Ł, Szepietowski JC. Psoriasis flare-up associated with second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech BNT16B2b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(10):e632–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17449.

Huang YW, Tsai TF. Exacerbation of psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination: report from a single center. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8: 812010. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.812010.

Munguía-Calzada P, Drake-Monfort M, Armesto S, Reguero-Del Cura L, López-Sundh AE, González-López MA. Psoriasis flare after influenza vaccination in Covid-19 era: a report of four cases from a single center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(1): e14684. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.14684.

Nagrani P, Jindal R, Goyal D. Onset/flare of psoriasis following the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 corona virus vaccine (Oxford-AstraZeneca/Covishield): report of two cases. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5): e15085. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15085.

Cazzato G, Romita P, Foti C, Cimmino A, Colagrande A, Arezzo F et al. Purpuric skin rash in a patient undergoing Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccination: histological evaluation and perspectives. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9070760.

Mazzatenta C, Piccolo V, Pace G, Romano I, Argenziano G, Bassi A. Purpuric lesions on the eyelids developed after BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: another piece of SARS-CoV-2 skin puzzle? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(9):e543–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17340.

Sandhu S, Bhatnagar A, Kumar H, Dixit PK, Paliwal G, Suhag DK, et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis as a cutaneous manifestation of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 corona virus vaccine (recombinant). Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(6): e15141. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15141.

Mücke VT, Knop V, Mücke MM, Ochsendorf F, Zeuzem S. First description of immune complex vasculitis after COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):958. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06655-x.

Erler A, Fiedler J, Koch A, Heldmann F, Schütz A. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis after vaccination with a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(12):2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41910.

Fiorillo G, Pancetti S, Cortese A, Toso F, Manara S, Costanzo A, et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis) after COVID-19 vaccination. J Autoimmun. 2022;127: 102783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2021.102783.

Uh JA, Lee SK, Kim JH, Lee JH, Kim MS, Lee UH. Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis after ChAdOx1 COVID-19 vaccination: a report of five cases. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21(2):193–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/15347346221078734.

Kar BR, Singh BS, Mohapatra L, Agrawal I. Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis following COVID-19 vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(11):3382–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14452.

Dash S, Behera B, Sethy M, Mishra J, Garg S. COVID-19 vaccine-induced urticarial vasculitis. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(5): e15093. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15093.

Kaminetsky J, Rudikoff D. New-onset vitiligo following mRNA-1273 (Moderna) COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(9): e04865. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.4865.

Militello M, Ambur AB, Steffes W. Vitiligo possibly triggered by COVID-19 vaccination. Cureus. 2022;14(1): e20902. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20902.

Herzum A, Micalizzi C, Molle MF, Parodi A. New-onset vitiligo following COVID-19 disease. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2(1): e86. https://doi.org/10.1002/ski2.86.

Uğurer E, Sivaz O, Kıvanç Aİ. Newly-developed vitiligo following COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(4):1350–1. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14843.

Ciccarese G, Drago F, Boldrin S, Pattaro M, Parodi A. Sudden onset of vitiligo after COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(1): e15196. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15196.

Koç YS. A new-onset vitiligo following the inactivated COVID-19 vaccine. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21(2):429–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14677.

Singh R, Cohen JL, Astudillo M, Harris JE, Freeman EE. Vitiligo of the arm after COVID-19 vaccination. JAAD Case Rep. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.003.

Ricciotti TGH. Should I get a COVID-19 vaccine if I’ve had dermal fillers? Harvard Health Publishing. 2021.

Petronelli M. Guidance issued for COVID-19 vaccine side effects in dermal filler patients. Dermatology Times. 2021.

Osmond A, Kenny B. Reaction to dermal filler following COVID-19 vaccination. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(12):3751–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14566.

Munavalli GG, Guthridge R, Knutsen-Larson S, Brodsky A, Matthew E, Landau M. COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 virus spike protein-related delayed inflammatory reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal fillers: a challenging clinical conundrum in diagnosis and treatment. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;314(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-021-02190-6.

Munavalli GG, Knutsen-Larson S, Lupo MP, Geronemus RG. Oral angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors for treatment of delayed inflammatory reaction to dermal hyaluronic acid fillers following COVID-19 vaccination–a model for inhibition of angiotensin II-induced cutaneous inflammation. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:63–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2021.02.018.

Michon A. Hyaluronic acid soft tissue filler delayed inflammatory reaction following COVID-19 vaccination – a case report. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20(9):2684–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14312.

Savva D, Battineni G, Amenta F, Nittari G. Hypersensitivity reaction to hyaluronic acid dermal filler after the Pfizer vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113:233–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.066.

Barry M, AlRajhi A, Aljerian K. Pyoderma gangrenosum induced by BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine in a healthy adult. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10010087.

Clark AL, Williams B. Recurrence of pyoderma gangrenosum potentially triggered by COVID-19 vaccination. Cureus. 2022;14(2): e22625. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22625.

Mohd AB, Mohd OB, Ghannam RA, Al-Thnaibat MH. COVID-19 vaccine: a possible trigger for pyoderma gangrenosum. Cureus. 2022;14(5): e25295. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.25295.

Maranini B, Ciancio G, Corazza M, Ruffilli F, Galoppini G, Govoni M. Erythema nodosum after COVID-19 vaccine. Reumatismo. 2022;74(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/reumatismo.2022.1475.

Teymour S, Ahram A, Blackwell T, Bhate C, Cohen PJ, Whitworth JM. Erythema nodosum after Moderna mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35(4): e15302. https://doi.org/10.1111/dth.15302.

Juddoo V, Juddoo S, Mégarbane B. Erythema nodosum triggered by BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine. 2022;40(19):2650–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.03.052.

Alzoabi N, Alqahtani J, Algamdi B, Almutairi M, Alratroot J, Alkhaldi S, et al. Atypical presentation of erythema nodosum following Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Med Arch. 2022;76(1):72–4. https://doi.org/10.5455/medarh.2022.76.72-74.

Aly MH, Alshehri AA, Mohammed A, Almalki AM, Ahmed WA, Almuflihi AM, et al. First case of erythema nodosum associated with Pfizer vaccine. Cureus. 2021;13(11): e19529. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19529.

Xie Y, Yin B, Shi X. Erythema nodosum following SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18304.

Chahed F, Ben Fadhel N, Ben Romdhane H, Youssef M, Ben Hammouda S, Chaabane A, et al. Erythema nodosum induced by Covid-19 Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine: a case report and brief literature review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.15351.

Cameli N, Silvestri M, Mariano M, Bennardo L, Nisticò SP, Cristaudo A. Erythema nodosum following the first dose of ChAdOx1-S nCoV-19 vaccine. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36(3):e161–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17762.

Mansouri P, Chalangari R, Martits-Chalangari K, Mozafari N. Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to COVID-19 vaccination. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(11): e05099. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccr3.5099.

Bakir M, Almeshal H, Alturki R, Obaid S, Almazroo A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis post COVID-19 vaccination – first reported case. Cureus. 2021;13(8): e17215. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.17215.

Yousaf AR, Cortese MM, Taylor AW, Broder KR, Oster ME, Wong JM, et al. Reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children aged 12–20 years in the USA who received a COVID-19 vaccine, December 2020, through August, 2021: a surveillance investigation. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(5):303–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(22)00028-1.

Callaway E. What Omicron's BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. Nature. 2022;606(7916):848–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01730-y.

Heath PT, Galiza EP, Baxter DN, Boffito M, Browne D, Burns F, et al. Safety and efficacy of NVX-CoV2373 Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(13):1172–83. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2107659.

Krouse HJ. COVID-19 and the widening gap in health inequity. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):65–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820926463.

Dorn AV, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395(10232):1243–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30893-x.

Doumas M, Patoulias D, Katsimardou A, Stavropoulos K, Imprialos K, Karagiannis A. COVID19 and increased mortality in African Americans: socioeconomic differences or does the renin angiotensin system also contribute? J Hum Hypertens. 2020;34(11):764–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-020-0380-y.

Vasquez RM. The disproportional impact of COVID-19 on African Americans. Health Hum Rights. 2020;22(2):299–307.

Organization WH. COVAX: working for global equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines. 2022.

Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Hruza GJ, Irvine AD, Spuls PI, Smith CH, et al. International collaboration and rapid harmonization across dermatologic COVID-19 registries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):e261–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.050.

Wall D, Alhusayen R, Arents B, Apfelbacher C, Balogh EA, Bokhari L, et al. Learning from disease registries during a pandemic: moving toward an international federation of patient registries. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39(3):467–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.01.018.

Shi V, Hsiao JL, Shi VY. COVID-19 skin manifestations: the new great imitator? Dermatol Online J. 2020;26(11).

••Visconti A, Murray B, Rossi N, Wolf J, Ourselin S, Spector TD, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection during the Delta and Omicron waves in 348,691 UK users of the UK ZOE COVID study app. Br J Dermatol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21784. This reference is considered important as it is one of the largest studies or registries that report significant data on COVID-19 infection and COVID-19 vaccine related cutaneous reactions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

E.F. is supported by ILDS: COVID-19 Dermatology Registry funding and NIH K23 grant on pernio/chilblains in COVID pandemic. R.S. has nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Covid-19 in Dermatology

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, R., Freeman, E.E. Viruses, Variants, and Vaccines: How COVID-19 Has Changed the Way We Look at Skin. Curr Derm Rep 11, 289–312 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-022-00370-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-022-00370-9