Abstract

We study what makes for a good job, by looking at which workplace characteristics are conducive or detrimental to job satisfaction. Using data from 37 countries around the world in the 2015 Work Orientations module of the International Social Survey Programme, we find that having an interesting job and good relationships at work, especially with management, are the strongest positive predictors of how satisfied employees are with their jobs, along with wages. Stressful or dangerous jobs, as well as those that interfere with family life, have the strongest negative correlation with job satisfaction. We discuss implications for firms and other organisations as well as for public policy-makers, and point toward future avenues for research in the area.

An extended version of this chapter was published as Krekel, C., G. Ward, and J.-E. De Neve, “Work and Wellbeing: A Global Perspective,” in: Sachs, J. (ed), Global Happiness Policy Report, 2018. An online appendix with additional tables and figures (as well as full replication materials) can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0EEOTM. For helpful advice and comments, we are very grateful to Amy Blankson, Andrew Clark, Cary Cooper, Ed Diener, Jim Harter, John Helliwell, Jenn Lim, Richard Layard, Paul Litchfield, Ewan McKinnon, Jennifer Moss, Mike Norton, Mariano Rojas, Jeffrey Sachs, Martin Seligman, and Ashley Whillans.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Work plays a central role in most people’s lives. In OECD countries, for example, people spend around a third of their waking hours in paid work.Footnote 1 Not only do we spend considerable amounts of our time at work, but work and employment also frequently rank among the most important drivers of how happy we are in our lives overall.Footnote 2 Yet, what exactly is it about work – and the characteristics of different jobs and workplaces – that makes some jobs more enjoyable and others less so? In this chapter, we shed light on this question by examining the ways in and extent to which workplace and job characteristics are associated with subjective wellbeing.

The question of what makes for a satisfying work life is not only important because work plays such a significant role for people’s overall wellbeing, but also because people’s wellbeing is a significant predictor of important labour market outcomes themselves (De Neve and Oswald 2012). Such outcomes include job-finding and future job prospects when people are out of work (Krause 2013; Gielen and van Ours 2014), productivity while they are in work, and, ultimately, their firms’ performance (Harter et al. 2002; Edmans 2011, 2012; Bockerman and Ilmakunnas 2012; Tay and Harter 2013; Oswald et al. 2015; Krekel et al. 2019).Footnote 3 Being happier also brings with it objective benefits such as increased health and longevity, which themselves can contribute positively to work outcomes (De Neve et al. 2013; Graham 2017). Likewise, wellbeing has been shown to be positively associated with intrinsic motivation and creativity (Amabile 1996; Amabile and Kramer 2011; Yuan 2015). For policy-making, which often boils down to prioritising attention and resources, it is important to know which characteristics of work, and workplace quality, most strongly drive people’s wellbeing. This can help point the way towards what should be focused upon in any efforts to improve overall wellbeing, which is an important good in itself, and in doing so potentially unlock any subsequent performance gains.

This chapter looks at these characteristics in a systematic way. We employ data from the International Social Survey Programme, a dataset that comprises nationally representative samples of 37 countries around the world, and includes information on a wide array of working conditions and job characteristics, as well as subjective wellbeing. We study the extent to which each of these characteristics is associated with job satisfaction – an important domain of people’s overall subjective wellbeing (Easterlin 2006) – and then complement these analyses with findings from the academic literature. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the implications for firms and policy-makers, as well as of important areas for future research.

2 Data and Methods

Our principal data source is the Work Orientations module of the 2015 International Social Survey Programme. Our outcome of interest is job satisfaction. Respondents are asked: “How satisfied are you in your main job?” The question offers six answer possibilities, including “completely satisfied”, “very satisfied”, “fairly satisfied”, “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied”, “fairly dissatisfied”, and “very dissatisfied”. We assign numerical values to these categories, and use the indicator as a cardinal measure. We then standardise it such that it has mean zero and standard deviation one.

Not only does this measure offer a distinctively democratic way of asking people what exactly makes a good job, but it is also strongly correlated with employee retention, an outcome that is itself highly important to firm performance. In fact, if we correlate job satisfaction with the willingness of employees to turn down a competing job offer, which is also reported in this survey, we obtain a sizeable correlation coefficient of about 0.4, suggesting that employees who are more satisfied with their jobs are also, to a large extent, more likely to remain in their jobs.

Our goal is to find out which elements of workplace quality explain job satisfaction, our outcome of interest. Within a multivariate linear regression framework, we regress job satisfaction on various domains of workplace quality as well as a rich set of control variables. Building on Clark (2009), we define twelve domains:

-

Pay

-

Working Hours

-

Working Hours Mismatch

-

Work-Life Balance

-

Skills Match

-

Job Security

-

Difficulty, Stress, Danger

-

Opportunities for Advancement

-

Independence

-

Interesting Job

-

Interpersonal Relationships

-

Usefulness

In some cases, a domain includes a single element, as in case of working hours (it simply includes the actual working hours of the respondent). In other cases, a domain includes several elements. For example, Pay includes both the actual income of the respondent and her subjective assessment of whether that income is high. In such cases, we conduct a principle component analysis to extract a single, latent explanatory factor from these elements, and then relate job satisfaction to this factor. In other words, we first establish which broad domains of workplace quality are relatively more important for job satisfaction than others, and then go on to look at the different elements within these domains in order to measure their specific contribution to job satisfaction.

As with our outcome, we standardise our explanatory variables such that they have mean zero and standard deviation one. This makes interpretation easier: the coefficient estimate of an explanatory variable is the partial correlation coefficient and, when squared, indicates the variation in job satisfaction that this variable explains.

To account for potentially confounding individual characteristics of respondents that may drive both working conditions and wellbeing, we control for a rich set of demographic variables by holding them constant in our regression. These include a wide array of individual demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and education. In the appendix, we provide full definitions as well as summary statistics of job satisfaction, the different elements of workplace quality, and the control variables.

In our main specification, we also include industry and occupation fixed effects. It is quite imaginable that there are significant differences in job satisfaction between different occupations and industries. We are not principally interested in explaining level differences in job satisfaction between, for example, a manager in the pharmaceutical industry and a farmer. Instead, we are interested in answering the more fundamental question of which broad domains of workplace quality are relatively more important for job satisfaction than others in more directly comparable occupations and industries.Footnote 4 Finally, we control for the respective country in which the respondent lives, for the same reason, and restrict the sample to private households with individuals who report to be working (regardless of age or how many hours).

3 Results

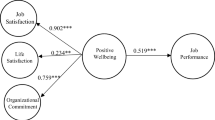

We now turn to our regression results, and look more deeply into which of these domains of workplace quality are relatively more important for job satisfaction than others. Figure 11.1 plots the coefficient estimates obtained from our regression of job satisfaction on the different domains. The corresponding, more detailed regression results are available in Table 11.1. Table 11.2 employs, instead of the broad domains of workplace quality, the different constituent elements within these domains.Footnote 5

Workplace quality and job satisfaction (International Social Survey Programme, Module on Work Orientations, Year 2015; 95% Confidence Intervals). (Notes: The figure plots effect estimates obtained from regressing job satisfaction on different domains of workplace quality. All variables (both left and right-hand side) are standardised with mean zero and standard deviation one. Squaring a regressor yields the respective share in the variation of job satisfaction that this regressor explains. Pay, Working Hours Mismatch, Work-Life Imbalance, Skills Match, Difficulty, Stress, Danger, Independence, Interpersonal Relationships, and Usefulness are principle components obtained from separate principle component analyses that condense various variables in the respective domain of workplace quality into a single indicator; see Section 2 for a description of the procedure and Table W8 in the Web Appendix for summary statistics of the variables. The sample is restricted to all individuals who state that they are working and who report working hours greater than zero. See Table 11.1 for the corresponding table)

In what follows, we discuss, in turn, the relative importance of the different domains of workplace quality, including, where appropriate, the different elements within these domains, for job satisfaction. We look mostly at their association with job satisfaction for the average employee, but, where interesting, point towards effect heterogeneities between the employed and the self-employed (Fig. 11.2a), full-time and part-time (Fig. 11.2b), and between basic demographic characteristics such as gender (Fig. 11.2c) and different levels of education (Fig. 11.2d).

3.1 Pay

It may come as little surprise that we find pay to be an important determinant of job satisfaction. In classic economic theory, labour enters the utility function negatively, and theory predicts that individuals are compensated by wages that equal the marginal product of labour. That said, pay is not only an important compensation for the hardship that individuals incur when working but also an important signal of their productivity. We thus expect job satisfaction to be higher the greater the wedge between compensation and hardship incurred, and the more social-status relevant pay is.

The importance of pay for job satisfaction seems universal, with no statistically significant differences between respondents who are employed or self-employed and working full-time or part-time, or between gender and different levels of education. In our analysis, the domain Pay consists of two elements: the actual income of respondents and their subjective assessment of whether that income is high. Both elements are almost equally important, but objective income a little more.

Perhaps more surprising is the finding that, although pay is an important determinants of job satisfaction, it is not the most important one. In fact, it only ranks third, behind interpersonal relationships at work and having an interesting job. We discuss these determinants in detail below.

Most people, when being asked why they are working, respond that they are working to earn money. This is, of course, true, but once they are working, other workplace characteristics become more salient, and thus potentially more important than previously thought. Experimental research, for example, has shown that intrinsic motivations gain in importance relative to extrinsic ones (such as income) once individuals are engaged in an activity (Woolley and Fishbach 2015). Purpose, in particular, may be such a characteristic: Ariely et al. (2008) show, in a laboratory setting, that people who see a purpose in what they do perform relatively better at work, even in the context of simple, repetitive effort tasks.Footnote 6 Using both experimental and observational data, Hu and Hirsh (2017) find that employees report minimum acceptable salaries that are 32% lower for personally meaningful jobs compared to jobs that are perceived as personally meaningless. The important role of purpose may be even more pronounced when in interplay with good management practices (Gartenberg et al. 2016), including employee recognition (Bradler et al. 2016).

3.2 Working Hours

As labour enters the utility function negatively, classic economic theory predicts a negative relationship between the number of working hours and wellbeing. This is precisely what we find for job satisfaction.

Interestingly, however, when controlling for all other domains of workplace quality, the relationship between working hours and job satisfaction is not only tiny (it ranks as the least important domain of workplace quality) but turns out to be statistically insignificant altogether. This finding is again universal: there are no statistically significant differences between respondents who are employed or self-employed and working full-time or part-time, or between gender and different levels of education.

This seems odd at first, but as we shall see below, is in line with a growing evidence base that documents the negative impact of working hours mismatch and work-life imbalance on people’s wellbeing.

3.3 Working Hours Mismatch

Rather than the total number of working hours, what seems to matter more for job satisfaction is working hours mismatch, defined as the difference between the actual and the desired number of working hours.

Individuals differ in their preferences for how much they want to work, and classic economic theory assumes that they can freely choose their desired bundle of labour and leisure hours. Empirical evidence, however, suggests that this is often not the case: work contracts, labour market conditions, and social norms, amongst others, may affect their choices, and may lead to a realised bundle that is different from the desired one. In Britain, for example, more than 40% of employees who work full-time report to prefer working fewer hours (Boeheim and Taylor 2004). In such situations, theory predicts that individuals end up on a lower utility level.

Working hours mismatch has a significant negative association with how satisfied employees are, on average, with their jobs. It is still unsettled in the literature, however, whether underemployment is more detrimental to people’s wellbeing, as has been found for Germany (Wunder and Heineck 2013), or overemployment, as has been found for Australia (Wooden et al. 2009) or Britain (Angrave and Charlwood 2015). In our analysis, the domain Working Hours Mismatch consists of two elements: the desire to work more hours (for more pay) and the desire to work less hours (for less pay). We find that the latter drives the tempirical linkage of working hours mismatch to job satisfaction, suggesting that overemployment is more of an issue than underemployment. Diverging results in the literature may point towards the importance of accounting for differences in institutional settings between countries, including, for example, differences in labour market regulations (especially regarding job security), social policy, social norms, and lifestyles. Note that working hours mismatch has also been found to have negative spillovers on other household members (Wunder and Heineck 2013).

It turns out that the negative association between working hours mismatch and job satisfaction is driven primarily by the employed as opposed to the self-employed (who probably have more control over their working hours) and, in line with our finding for overemployment, by employees working full-time as opposed to part-time.

Importantly, there is a gender dimension to working hours mismatch: its negative association with job satisfaction is driven primarily by women. Evidence shows that women spend considerably larger amounts of time caring for other household members (for example, they spend more than twice as much time on childcare) and doing routine household work than men, even in the case that actual working hours are equal between women and men (OECD 2014). For women, achieving a better balance between the actual and the desired number of working hours would therefore be an effective means of reducing time crunches. The fact that working fewer hours may be detrimental to their long-term career prospects presents a dilemma, and may – at least in part – explain the declining life satisfaction of mothers over the past decades (Stevenson and Wolfers 2009).

In sum, we find that working hours mismatch, in particular overemployment, has a significant negative impact on job satisfaction. The size of this association, however, is rather small: in fact, working hours mismatch is only ranked eleventh out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of their importance for job satisfaction. If working hours mismatch is not so bad after all, then what is? The answer is work-life imbalance.

3.4 Work-Life Balance

Working hours mismatch may not be so bad as long as it does not seriously interfere with other important domains of life, especially the family. If, however, work and private life threaten to get out of balance, negative consequences for people’s wellbeing are large.

Although work-life (im)balance ranks only fourth out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction, it is the domain that has the strongest negative impact on job satisfaction amongst all negative workplace characteristics. It is highly significant, and statistically indistinguishable from having a job that is difficult, stressful, or even dangerous. The negative association between work-life imbalance and job satisfaction job satisfaction seems to be almost universal: there are no statistically significant differences between respondents who are employed or self-employed and between gender. Perhaps not surprisingly, employees working full-time are more heavily affected than those working part-time, and there is some evidence that the negative consequences of work-life imbalance are stronger for workers with low levels of education.

In our analysis, the domain Work-Life Balance consists of three elements, which have a clear ranking in terms of importance: work interfering with the family exerts, by far, the strongest negative impact on job satisfaction, followed by the difficulty of taking time off on short notice when needed. The coefficient for working on weekends actually suggests a positive relationship, but is negligible in terms of effect size.

From our findings on working hours mismatch and work-life balance, we can derive some important policy implications: policies that target more supportive and flexible working time regulations have the potential to considerably increase people’s wellbeing. This is especially true for people who experience disproportionally more time crunches, including, amongst others, women, parents (especially single parents), and caretakers of other household members such as elderly. The public policy mix that enables people to strike a better balance between their work and private lives can be quite diverse, ranging from specific labour market regulations on flexible working times to the provision of infrastructure such as public transportation in order to reduce commuting times or early childcare facilities in sufficient quantity and quality. At the same time, for firms, offering more flexible working times may be a promising strategy to effectively attract and retain skilled workers.

Is there a trade-off between flexible work practices and performance? To answer this question, Bloom et al. (2014) conducted an experiment at Ctrip, a NASDAQ-listed Chinese travel agency with more than 16,000 employees. The authors randomly allocated call centre agents who volunteered to participate in the experiment to work either from home or in the office for 9 months. They found that working from home led to a 13% performance increase, due to fewer breaks and sick days as well as a quieter and more convenient working environment. At the same time, job satisfaction rose and attrition halved. Conditional on their performance, however, participants in the experiment were less likely to get promoted.Footnote 7

For employees, of course, this raises the question of whether flexible work practices are associated with a career penalty. This does not necessarily have to be the case: Leslie et al. (2012) show, in both a field study at a Fortune 500 company and a laboratory experiment, that flexible work practices result in a career penalty only in case that managers attribute their use as being motivated primarily by reasons related to personal lives. To the extent that mangers attribute their use to reasons related to organisational needs, however, their use can actually result in a career premium. The latter category includes reasons related to, for example, work performance and efficiency. Part of this attribution is communication, and training supervisors on the value of demonstrating support for employees’ personal lives while prompting employees to reconsider when and where to work can help reduce work-family conflict (Kelly et al. 2014).

Finally, Moen et al. (2011) studied the turnover effects of switching from standard time practices to a results-only working environment at Best Buy, a large US retailer that implemented the scheme sequentially in its corporate headquarters: eight months after implementation, turnover amongst employees exposed to the scheme fell by 45.5%. Evidence therefore suggests that carefully designed, implemented, and communicated flexible work schemes can actually have positive impacts on organisational performance.

3.5 Skills Match

A job that is asking too much from the skills of an employee can lead to frustration, and so can a job that is asking too little. Matching the demand for and the supply of skills in a particular job, and enabling employees to effectively apply the skills they have or, if necessary, to acquire new skills, should thus be reflected in higher job satisfaction.

This is precisely what we find. Achieving a skills match in a particular job has a significant positive association with how satisfied employees are with that job. This is again an almost universal finding: there are no statistically significant differences between respondents who are employed or self-employed, between respondents who are working full-time or part-time, and between gender. Differences between levels of education are minor. The domain Skills Match includes two elements: whether respondents have participated in a skills training in the previous year and their subjective assessment of whether their skills generally match those required in their job. Both elements matter, but their subjective assessment a little more.Footnote 8 Importantly, skills match is not only directed towards the self but also towards others in the workplace. In fact, Artz et al. (2017) find that supervisor technical competence is amongst the strongest predictors of workers’ job satisfaction. Willis Towers Watson, a leading human resources consultancy, estimates that in companies where leaders and managers are perceived as effective, 72% of employees are highly engaged (Willis Tower Watson 2014). On a more abstract level, the concept of skills match may also be applied to matching individual character strengths, although there is yet little evidence on the causality of this relationship in organisational settings.

Although skills match ranks only ninth out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction, places five to nine are close to each other, and thus constitute a category of medium importance for wellbeing at work.

What are the wellbeing returns to essential skills training in practice? UPSKILL was a workplace literacy and essential skills training pilot in Canada (Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, 2014a). It was implemented as a randomised controlled trial, involving 88 firms (primarily in the accommodation and food services sector) and more than 800 workers who were randomly allocated to receiving 40 hours of literacy and skills training on site during working hours. The pilot was not only effective in increasing basic literacy scores and thus job performance and retention, but, importantly, also in increasing mental health: at follow-up, participants in the treatment group were 25% points more likely than those in the control group to have reported a significant reduction in stress levels. Effects were particularly pronounced amongst participants with low baseline skills at the outset. These positive impacts at the worker level also translated into positive impacts at the firm level: even though firms bore the full costs of training and release time for workers, they incurred a 23% return on investment, primarily though gains in revenue (customer satisfaction increased by 30% points), cost savings from increased productivity (wastage and errors in both core tasks and administrative activities were significantly reduced), and reductions in hiring costs. Besides firms’ commitment to learning and training, organisations that offered work environments with high levels of trust gained relatively more from the programme (Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, 2014b). This is in line with a growing evidence base on the importance of trust in the workplace (Helliwell et al. 2009; Helliwell and Huang 2011; Helliwell and Wang 2015).

3.6 Job Security

Slightly more important than skills match is job security: it ranks sixth out of twelve domains of workplace quality, and is thus also part of the category of medium importance for wellbeing at work.

Job security is universally important: we find no evidence of effect heterogeneities between respondents who are employed or self-employed and working full-time or part-time, or between gender and different levels of education. The literature shows that the unemployment rate in a particular region has a significant negative effect on the life satisfaction of the employed in that region (Luechinger et al. 2010). This is often interpreted as a signal of general job insecurity, which is detrimental to happiness.

3.7 Difficulty, Stress, Danger

Not surprisingly, we find that jobs which are associated with difficulty, stress, or even danger are also associated with lower levels of job satisfaction. This holds true even when controlling for all other domains of workplace quality, including pay, working hours, and job security. This is an interesting finding in itself, as classic economic theory predicts that workers should be compensated, either monetarily or non-monetarily, for any job disamenities such that the net wellbeing effect is zero. Empirical evidence on so-called compensating differentials, however, is rather mixed. In our data, which are clearly limited (for example, we are not fully able to account for ability differences), we find little evidence of them.

In our analysis, the domain Difficulty, Stress, Danger consists of two elements: hard physical and stressful work. It turns out that the latter drives the negative empirical linkage of this domain to job satisfaction; the former, on the contrary, turns out statistically insignificant. The fact that stress at work is detrimental to health is well-established in the literature: for example, Chandola et al. (2006), in a large-scale prospective cohort study involving more than 10,000 men and women aged 35 to 55 who were employed in 20 London civil service departments, study the relationship between exposure to stressors at work and the risk of developing the metabolic syndrome, a cluster of at least three of five medical conditions including, amongst others, obesity, high blood pressure, and high blood sugar. They find that employees with chronic work stress were more than twice as likely to develop the syndrome 14 years into the study than those without.

Having a job that is difficult, stressful, or even dangerous ranks fifth out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. It is the domain that has the second strongest negative association with job satisfaction amongst all negative workplace characteristics, and comes right after work-life imbalance from which it is – at least in terms of effect size – statistically not distinguishable. We find little evidence that its negative impact varies for different people.

3.8 Opportunities for Advancement

We know from the literature that being in a stable employment relationship, be it full-time or part-time, has a positive relationship with how people evaluate their lives globally, as well as how they feel on a daily basis. Part of why this is the case is that jobs provide opportunities for advancement, be it steps to climb up the career ladder, new challenges that give room for personal development, and many others.

Our data do not discriminate between different types of opportunities for advancement, but simply ask respondents whether their current job provides them. This gives respondents the freedom to interpret the question in whatever way they themselves find most important.

We find that opportunities for advancement have a significant positive impact on the job satisfaction of the average respondent. There is quite some effect heterogeneity, though: the association is primarily driven by respondents who are employed as opposed to self-employed (probably because the self-employed are themselves more in control of which opportunities for advancement to create or not) and by respondents who work full-time as opposed to part-time. There also seems to be a gradient in education: opportunities for advancement become more important for job satisfaction the higher the level of education. They are equally important to men and women.

Opportunities for advancement rank seventh out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. Perceived progress through well-defined goal-setting and planning as well as measurable evaluations – based on clearly defined expectations and performance – and employee recognition may increase agency and make the way towards career advancement more transparent, thereby contributing positively to wellbeing at work.

3.9 Independence

Independence at work can have many facets. Our survey asks respondents to what extent they can work independently, whether they often work at home, and whether they have agency about the organisation of their daily work, their working hours, and their usual working schedule.

We find that independence at work occupies the middle ground of importance for wellbeing: it has a significant positive relationship with job satisfaction, with an effect size similar to skills match, job security, opportunities for advancement, and usefulness. It is ranked eighth out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. Independence at work seems to be important to everybody: there are no statistically significant differences between respondents who are employed or self-employed and working full-time or part-time, or between gender and different levels of education.

In our analysis, the domain Independence includes eight elements: the subjective assessment of respondents as to what extent they can work independently, how often they work at home during their usual working hours, and whether the organisation of their daily work, their working hours, and their usual working schedule is entirely free for them to decide as opposed to fixed. Some of these elements are important, others are not. There also seems to be a ranking of importance: we find that the positive impact of independence at work on job satisfaction is driven primarily by whether respondents report that they can freely organise their daily work, followed by their subjective assessment as to what extent they can work independently. The nature of having discretion about the usual working schedule is more complex: we find that both full discretion and no discretion at all have a negative impact on job satisfaction. Here, it seems that the reference category – having limited discretion – yields a higher job satisfaction than both ends of the spectrum.

Independence at work is related to the concept of job crafting (Wrzesniewski and Dutton 2001), and the question of whether organisations should give their employees, to a certain extent, the freedom to design their jobs based on personal needs and resources. Studies have shown that enabling employees to craft their jobs in this way can have positive benefits in terms of increased employee engagement and job satisfaction as well as decreased likelihood of burnout (Tims et al. 2013). More generally, the concept of individual job crafting may be transferred to the level of the entire organisation, in the sense of organisational design. It can also be applied to the physical environment: Knight and Haslam (2010) studied, in an experiment involving different office spaces, the effect of giving employees the opportunity to design their physical working environment. In line with the notion of social identity, they found that employees who were randomly allocated to the crafting condition showed higher organisational identification, job satisfaction, and productivity, measured in terms of task performance. Independence at work has also been identified as a contributing factor to creativity (Amabile et al. 1996). Evidence is thus rather positive about independence at work, but its precise impact is probably highly context-specific.

Does autonomy over working schedules raise employee wellbeing? STAR (“Support. Transform. Achieve. Results”) was a flexible working practices pilot developed by the interdisciplinary Work Family and Health Network (King et al. 2012). It aimed at (i) increasing employees’ control over their working schedule, (ii) raise employee perceptions of supervisor support for their personal and family lives, and (iii) reorient the working culture from face time to results only. Eight hours of preparatory sessions encouraged managers and their teams to identify new, flexible work practices, for example, by communicating via instant messenger or by planning ahead periods of peak-demand more effectively. The pilot was implemented as a group-randomised controlled trial in a Fortune 500 company, involving 867 IT workers who were, including their entire team, allocated to either the intervention or business-as-usual and followed for over a year. Moen et al. (2016) find that the intervention significantly reduced burnout by about 44% of a standard deviation while raising job satisfaction by about 30%. These large effect sizes were partially mediated by decreases in family-to-work conflict and, perhaps less surprisingly, increases in schedule control. There is also some evidence that the intervention decreased perceived stress and psychological distress. Although it has not been evaluated with respect to employee performance (possibly because it is difficult to measure performance in the given context), recent experimental evidence (see Bloom et al. (2014), for example) suggests that, in a very similar context, giving employees more autonomy over where and when to work can have strong, positive performance impacts.

3.10 Interesting Job

It should not come as a big surprise that having an interesting job is positively associated with being more satisfied with it.

But it is astonishing just how important interestingness is. Amongst all positive workplace characteristics, it has the second strongest impact on job satisfaction, right after interpersonal relationships at work (from which it is, in terms of effect size, not statistically distinguishable), and thus ranks second out of twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. There is little evidence that the impact of interestingness varies for different people: having an interesting job is important to everybody.

Note that interestingness is not the same as purposefulness. A job can score both high on being interesting and low on being purposeful. In contrast to interestingness, purposefulness is best described in terms of a long-term alignment between a job and an individual’s own evolutionary purpose in the sense of doing something greater than self.

3.11 Interpersonal Relationships

In most jobs, employees interact, in one way or another, with supervisors, co-workers, or clients.Footnote 9 The way in which these interactions occur, and interpersonal relationships are maintained, shows up as the most important determinant of how satisfied employees are with their jobs.

Interpersonal relationships have a sizeable, significant positive association with the job satisfaction of the average employee. They rank first out of our twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. The size of the relationship, however, is statistically not different from that of having an interesting job, which ranks second. Interpersonal relationships are particularly important for the employed as opposed to the self-employed (probably because the self-employed can, if necessary, avoid interactions) and employees who are working full-time as opposed to part-time (probably because people become relatively more important the more time is spent with them). There is no gender dimension to interpersonal relationships: they are equally important to men and women. Their importance for job satisfaction does not vary by educational level either.

In our analysis, the domain Interpersonal Relationships consists of three elements: contact with other people in general, the respondents’ subjective assessment of their relationship with the management, and the equivalent subjective assessment of their relationship with co-workers. The driver behind the positive impact of interpersonal relationships on job satisfaction is, by far, the relationship with the management. The relationship with co-workers is, although important, only half as important. This is in line with evidence showing that about 50% of US adults who have left their job did so in order to get away from their manager (Gallup News 2015). Contact with other people seems to matter less for job satisfaction.

How does the relationship between managers and employees affect wellbeing at work? Managers can have many functions: for employees, they may provide training, advice, and motivation (Lazear et al. 2015). To effectively fulfil these functions, managers should be competent. Artz et al. (2017) study the relationship between managers’ technical competence and employees’ job satisfaction, using the Working in Britain Survey in the UK and the National Longitudinal Study of Youth in the US. They find that a manager’s technical competence – measured in terms of whether the manager worked herself up the ranks, knows her job, or could even do the employee’s job – is the single strongest predictor of an employee’s job satisfaction. In terms of effect size, having a competent boss is even more important for job satisfaction than having friendly colleagues.

In a study on the National Health Service in England, Ogbonnaya and Daniels (2017) find that Trusts (the organisational entities the National Health Service is comprised of) which make the most use of people management practices are over twice as likely to have staff with the highest levels of job satisfaction as compared to those which make the least use of these practices. People management practices refer here to training, performance appraisals, team working, clear definition of roles and responsibilities, provision of autonomy in own decision-making, and supportive management that involves staff in organisational decisions. Importantly, they are also three times more likely to have the lowest levels of sickness absence, and four times more likely to have the most satisfied patients. White and Bryson (2013) confirm this finding for a wider range of organisations in Britain, using an index constructed from various domains of human resource management – participation, team working, development, selection, and incentives – and nationally representative, linked employee-employee data: firms with more human resource practices in place tend to score higher in terms of employees’ job satisfaction and organisational commitment (although the relationship seems to be non-linear).

Fairness and transparency in managerial decision-making seems to be an important factor as well: Heinz et al. (2017) conduct a field experiment in which the authors set up a call centre to study the impact of treating some employees unfairly on the productivity of the others. They set up two work shifts, and randomly lay off 20% of employees between shift one and two due to stated cost reductions (which, as confirmed by interviews with actual HR managers, is perceived as unfair). The productivity of the remaining, unaffected workers, which are notified by this decision at the beginning of the second shift, drops by about twelve percent. The effect size of the productivity decline is close to the upper bound of the direct effects of wage cuts.

3.12 Usefulness

How important is pro-sociality – doing something that is beneficial for other people or for society at large – when it comes to job satisfaction?

Pro-social behaviour is behaviour intended to benefit one or more individuals other than oneself (Eisenberg et al. 2013). This type of behaviour can cover a broad range of actions such as helping, sharing, and other forms of cooperation (Batson and Powell 2003).Footnote 10 It has been shown to have positive wellbeing benefits at the individual level (Meier and Stutzer 2008). At the societal level, it can help build social capital through fostering cooperation and trust, and social capital is linked to higher levels of wellbeing in societies (Helliwell et al. 2016, 2017). Pro-sociality is not the same as purpose (although they probably overlap to a very large extent): whereas pro-sociality is always directed towards others, purpose could, in the narrower sense, only be directed towards the self. That said, a job can score both high on individual purpose and low on pro-sociality. In reality, however, most jobs probably score either high or low on both constructs.

We can replicate this finding for wellbeing at work: doing something that is beneficial for other people or for society at large is associated with higher levels of job satisfaction, on average. However, in line with the notion of humans as conditional co-operators (Fehr and Fischbacher 2003), the size of this relationship is rather small. Usefulness ranks only tenth out of our twelve domains of workplace quality in terms of power to explain variation in job satisfaction. There is also quite some effect heterogeneity: doing something useful is more important for the job satisfaction of the employed as opposed to the self-employed (probably because the self-employed have, in the first place, more choice over which activities to engage in or not) and employees who are working full-time as opposed to part-time. Pro-sociality also becomes more important the higher the level of education. There are no significant differences between gender.

In our analysis, the domain Usefulness consists of two elements: helping other people and being useful to society. Both are important, but being useful to society a little more.

There is a growing literature on pro-sociality in the workplace. Anik et al. (2013) studied the impact of pro-social bonuses – a novel type of bonus spent on others rather than oneself – on wellbeing and performance. In a field experiment at a large Australian bank, the authors found that employees who were randomly allocated to receive bonuses in form of (relatively small) financial donations to be made to local charities showed significant, immediate improvements in job satisfaction and happiness compared to employees not given these bonuses. In two follow-up experiments, one involving sports teams in Canada and another one involving a sales team at a large pharmaceutical company in Belgium, they found that spending bonuses on team members rather than oneself led to better team performance in the longer term. The finding that spending money on others can buy you happiness has also been shown by Dunn et al. (2008): the authors find that pro-social spending in form of gifts to others or financial donations to charities is positively correlated with general happiness. Longitudinally, they show that (arguably otherwise comparable) employees who received – unexpectedly – a profit-sharing bonus and spent more of it pro-socially experienced an increase in general happiness, even after controlling for income and the amount of the bonus.

Two other intervention studies stand out: Gilchrist et al. (2016) studied the impact of pay rises – masked as gifts – on performance in a setting where there were no future employment possibilities. The authors hired one-time data entry assistants on an online platform for freelancers, and then randomly allocated them into different experimental conditions, one involving an unexpected, benevolent pay rise. They found that freelancers allocated to this condition entered 20% more data than those who were either initially offered the same pay or initially offered a lower pay, both of which performed equally. In other words, simply paying more at the outset did not elicit higher task performance, but an unexpected pay rise masked as a benevolent gift did. Grant (2008), in a randomised field experiment involving fund raisers at a university, found that bringing together fund raisers and beneficiaries to show the former the purpose of their work significantly increased their subsequent task performance.

How organisations can organise work to make it more fulfilling, and connect people with the pro-social impact they may have, for example, by providing incentives to elicit behaviours that help accumulating altruistic capital (Ashraf and Bandiera 2017), is a promising area of research.

4 Discussion

Despite the importance of work for people’s happiness, unfortunately, most people do not perceive work as a particularly enjoyable activity. A recent study that asked respondents to record their wellbeing via a smartphone at random points in time on a given day found that paid work is ranked lower than any other of the 39 activities sampled, with the exception of being sick in bed (Bryson and MacKerron 2016). In fact, the worst time of all seems to be when people are with their boss (Kahneman et al. 2004). Not surprisingly then, costs of absenteeism and presentism are high: in a recent report for the UK, it was estimated that absenteeism costs UK businesses about GBP 29 billion per year, with the average worker taking 6.6 days off due to sickness (PwC Research 2013). Costs of presentism due to, for example, mental health problems are estimated to be almost twice as high as those of absenteeism (The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health 2007). It is imperative, therefore, that we know which elements of work are least and most conducive to wellbeing, and how these might be changed in order to make work more satisfying.

This is not only important because work plays such a significant role for individuals’ overall wellbeing, but also because people’s wellbeing is an important predictor of outcomes related to worker productivity and firm performance. Harter et al. (2010), exploiting a large longitudinal dataset that includes 141,900 respondents within 2178 business units of ten large organisations across industries, study the relationship between perceived working conditions of employees and firm-level outcomes. They find that working conditions – including overall satisfaction within the organisation – are predictive of key outcomes such as employee retention and customer loyalty. Krekel et al. (2019) confirm a strong, positive relationship between employee satisfaction and customer loyalty, employee productivity, and firm profitability as well as a strong, negative relationship with staff turnover in a meta-analysis of 339 independent studies that include observations on the wellbeing of 1,882,131 employees and performance of 82,248 business units. Importantly, Harter et al. (2010) are able to show that the effect tends to run from working conditions to firm-level outcomes rather than the other way around – this is suggestive of a causal impact. The strength of the relationship is not trivial: in a previous meta-analysis, Harter et al. (2002) estimate that business units in the top quartile on employee engagement conditions realise between one and four percentage points higher profits and between 25% to 50% lower turnover than those in the bottom quartile.

These findings have direct implications for managerial practice. Frey (2017) argues that managers should create workplaces that are conducive to wellbeing, for example, by supporting workers’ independence and creativity or by fostering interpersonal relationships at work. At the same time, work should not be so demanding and burdensome that workers are unable to enjoy their leisure time. Providing more flexible working hours may be a means to strike a better balance between work and life. Income provided should be sufficient to lead a good life with respect to material standards. All of these factors have been found to be conducive to wellbeing at work, although to varying degrees. At the same time, however, Frey (2017) argues that managers should not engage in directly trying to maximising the happiness of stakeholders (which can be subject to manipulation). Rather, they should lay the foundations within organisations for stakeholders to achieve happiness in the way they choose themselves. The importance of autonomy, therefore, applies to the question of how to achieve happiness itself.

The importance of work, and workplace quality, in influencing wellbeing (as well as the impact of wellbeing on key firm-level outcomes) suggests there is a case for active policy intervention. Independent staff wellbeing audits may be one means to raise awareness for wellbeing at work. Awards for work environments that are conducive to wellbeing may also be bestowed on single managers or entire organisations (Gallus and Frey 2016; Frey and Gallus 2017). Systematic measurement of wellbeing within organisations may serve as a diagnostic tool, for example, to uncover wellbeing inequalities within organisations, which have been found to be a powerful driver of behaviour at the community level and may be relevant to organisations just as well. It may also serve as a vehicle to pave the way towards interventions, directed at one or more domains of workplace quality. The evidence presented here and reviewed elsewhere (see Arends et al. (2017) or OECD (2017b), for example) suggests that workplace quality has positive impacts on productivity and performance, in line with recent experimental evidence in various contexts (Bloom et al. 2014; Oswald et al. 2015). Ultimately, however, more experimental evidence from the field is needed in order to be able to make strong causal claims about the relationship between individual elements of workplace quality, wellbeing, and its objective benefits for both individuals and firms.

This chapter can only offer a cautious exploration into the nexus between work and wellbeing. Clearly, there are methodological issues: first, and foremost, the evidence presented here is mostly descriptive, and from descriptive evidence alone we cannot make causal statements. There may be characteristics of respondents that explain both workplace quality and their wellbeing at the same time. We need longitudinal data – repeated observations of the same individuals over time – to get closer to causal effects, and ideally, some sort of randomised experimental intervention or policy change as an exogenous variation in order to reduce concerns about self-selection and omitted variables. We bypassed this issue by presenting, where available, supporting evidence from causal-design studies in the literature.

Our tools are also limited in other dimensions – for example, in that our dataset is limited in terms of the outcome variable we employ. The latest module on Work Orientations of the International Social Survey Programme includes only job satisfaction as a domain-specific, evaluative measure of wellbeing. It is quite possible, however, that some workplace qualities are more likely to have a stronger impact either on eudemonic measures of wellbeing such as purpose or on hedonic measures of workplace mood. We cannot verify this with our data, and importantly, cannot check which construct is relatively more important for which domain of workplace quality. Ultimately, firms and policy-makers will likely be interested in tracking a set of evaluative, experiential, and eudemonic measures to give a more complete picture of wellbeing at work.Footnote 11

Concerning variables on workplace characteristics, most datasets today focus on rather standard items and ignore some of the more modern elements of labour markets related to technology and the future of work such as aspects pertaining to the so-called “gig economy” or (fear of) automation and artificial intelligence. Items sampled in different surveys are also quite heterogeneous. The OECD Guidelines on Measuring the Quality of the Working Environment, are therefore, a right step into the direction of establishing a unified framework for measuring workplace quality, focusing on objective job attributes and outcomes measured at the individual level (OECD 2017b). These guidelines divide job characteristics into six broad categories, including the physical and social environment of work, job tasks, organisational characteristics, working-time arrangements, job prospects, and intrinsic job aspects.

Finally, questions remain regarding external validity: while there are few datasets that are as comprehensive as the International Social Survey Programme, it is known from country-score comparisons with other datasets that some of its items have low convergent validity. Note, however, that similar findings on the relationship between workplace quality and job satisfaction have been identified by De Neve and Ward (2017) using the European Social Survey. Future research should be directed towards identifying similar patterns in other datasets. Importantly, this research should be seen as an ongoing endeavour: the composition of the labour supply changes continuously, for example, as more and more millennials with preferences different from previous generations enter the labour force.

In view of these limitations, we end this chapter by looking ahead, and appealing for more experimentation in the workplace: academics and businesses could and should cooperate to test how modifications to work processes and practices affect worker wellbeing, and ultimately, performance. Candidates for such modifications should be guided by theory, and tested in such a way as to be subject to rigorous impact evaluation through randomised controlled experiments. This way, we can avoid issues of omitted characteristics and self-selection, and identify causal effects of work and workplace quality on wellbeing and performance. It will be important to establish and agree on a common set of measures, covering evaluative, experiential, and eudemonic measures of wellbeing, to be used across impact evaluations. And it will be important to record and report the costs of these trials (less the costs of impact-evaluating them). This will allow for benchmarking interventions in terms of cost-effectiveness, and rank them according to which buy more worker wellbeing and performance per dollar invested. Evidence from behavioural science suggests that seemingly small, low-cost (or even costless) changes in daily work routines could produce large gains in wellbeing and performance.

Partly, this vision is already reflected in academic practice. Throughout the world, experimental methods are making their way onto curricula in the social sciences. Knowledge generated by way of field experiments should be shared openly as best practices, and doing so should be incentivised. Governments can also become active players themselves by introducing wellbeing interventions within the civil service, which could also help to promote happiness more widely in society. After all, a happy and engaged civil service is an obvious starting point for being able to deliver on policies that aim to put wellbeing at the heart of policy-making.

Notes

- 1.

See OECD (2017a) for data on daily time use in OECD countries.

- 2.

See Web Appendix Table W1, adapted from van Praag et al. (2003).

- 3.

- 4.

Of course, some of these domains are more prevalent in certain occupations and industries than in others.

- 5.

For a comprehensive summary of a systematic review on the relationship between job quality and wellbeing, see also What Works Centre for Wellbeing (2017a).

- 6.

The important role of purpose for performance has also been studied in educational contexts: Yeager et al. (2014) show that promoting a pro-social, self-transcendent purpose improves academic self-regulation in students.

- 7.

The company later offered the option to work from home to the whole firm, allowing formerly treated employees to re-select between working from home or working in the office: about half of them switched back, which almost doubled performance gains to 22%. This highlights the importance of accounting for self-selection and learning. In fact, in a recent discrete choice experiment, Mas and Pallais (2017) demonstrate that employee preferences for flexible work practices are quite heterogeneous: while most employees prefer a little extra income over flexibility, to a small number of employees, flexible work practices are very important.

- 8.

On the importance of learning on the job for wellbeing, see also What Works Centre for Wellbeing (2017b).

- 9.

On the importance of team work more generally for wellbeing, see What Works Centre for Wellbeing (2017c).

- 10.

Note that pro-social behaviour is distinct from altruism in that it is not purely motivated by increasing another individual’s welfare, but can be motivated by, for example, empathy, reciprocity, or self-image (Evren and Minardi 2017).

- 11.

For example, at the national level, following recommendations by Dolan and Metcalfe (2012), the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in the UK now routinely asks people how they think and feel about their lives, including four items, on evaluative (life satisfaction), experiential (happiness, anxiousness), and eudemonic (worthwhileness) measures of subjective wellbeing in its surveys.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in context: Update to the social psychology of creativity. London: Hachette UK.

Amabile, T., & Kramer, S. (2011). The progress principle: Using small wins to ignite joy, engagement, and creativity at work. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5), 1154–1184.

Angrave, D., & Charlwood, A. (2015). What is the relationship between long working hours, over-employment, under-employment and the subjective well-being of workers? Longitudinal evidence from the UK. Human Relations, 68(9), 1491–1515.

Anik, L., Aknin, L. B., Norton, M. I., Dunn, E. W., & Quoidbach, J. (2013). Prosocial bonuses increase employee satisfaction and team performance. PloS One, 8(9), e75509.

Arends, I., Prinz, C., & Abma, F. (2017). Job quality, health and at-work productivity. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers.

Ariely, D., Kamenica, E., & Prelec, D. (2008). Man’s search for meaning: The case of Legos. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 67(3–4), 671–677.

Artz, B. M., Goodall, A. H., & Oswald, A. J. (2017). Boss competence and worker well-being. ILR Review, 70(2), 419–450.

Ashraf, N., & Bandiera, O. (2017). Altruistic capital. American Economic Review, 107(5), 70–75.

Batson, C. D., & Powell, A. A. (2003). Altruism and prosocial behavior. In I. B. Weiner (Ed.), Handbook of psychology (Vol. 5). London: Wiley.

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2014). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165–218.

Böckerman, P., & Ilmakunnas, P. (2012). The job satisfaction-productivity nexus: A study using matched survey and register data. ILR Review, 65(2), 244–262.

Böheim, R., & Taylor, M. P. (2004). Actual and preferred working hours. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42(1), 149–166.

Bradler, C., Dur, R., Neckermann, S., & Non, A. (2016). Employee recognition and performance: A field experiment. Management Science, 62(11), 3085–3099.

Bryson, A., & MacKerron, G. (2016). Are you happy while you work? The Economic Journal, 127(599), 106–125.

Chandola, T., Brunner, E., & Marmot, M. (2006). Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ, 332(7540), 521–525.

Clark, A. (2009) Work, Jobs and Well-Being across the Millennium. IZA Discussion Paper, 3940.

De Neve, J. E., & Oswald, A. J. (2012). Estimating the influence of life satisfaction and positive affect on later income using sibling fixed effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 19953–19958.

De Neve, J. E., & Ward, G. (2017). Happiness at work. CEP Discussion Paper no. 1474.

De Neve, J. -E., Diener, E., & Tay, L., & Xuereb, C. (2013). The objective benefits of subjective well-being. In J. Helliwell, R. Layard, & J. Sachs (Eds.), World happiness report 2013. New York: UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Dolan, P., & Metcalfe, R. (2012). Measuring subjective wellbeing: Recommendations on measures for use by national governments. Journal of Social Policy, 41(2), 409–427.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688.

Easterlin, R. A. (2006). Life cycle happiness and its sources: Intersections of psychology, economics, and demography. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27(4), 463–482.

Edmans, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621–640.

Edmans, A. (2012). The link between job satisfaction and firm value, with implications for corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Perspectives, 26(4), 1–19.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Morris, A. S. (2013). Prosocial development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), Oxford handbook of developmental psychology (Vol. 2). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Evren, Ö., & Minardi, S. (2017). Warm-glow giving and freedom to be selfish. The Economic Journal, 127(603), 1381–1409.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2003). The nature of human altruism. Nature, 425(6960), 785.

Frey, B. S. (2017). Research on well-being: Determinants, effects, and its relevance for management. CREMA Working Paper, 2017–11.

Frey, B. S., & Gallus, J. (2017). Honour versus money. The economics of awards. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gallup News. (2015). Employees want a lot more from their managers, Online: http://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/182321/employees-lot-managers.aspx, Accessed 01 Dec 2017.

Gallus, J., & Frey, B. S. (2016). Awards: A strategic management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 37(8), 1699–1714.

Gartenberg, C., Prat, A., & Serafeim, G. (2016). Corporate purpose and financial performance. Harvard Business School Working Paper, 17-023.

Gielen, A. C., & van Ours, J. C. (2014). Unhappiness and job finding. Economica, 81(323), 544–565.

Gilchrist, D. S., Luca, M., & Malhotra, D. (2016). When 3+ 1> 4: Gift structure and reciprocity in the field. Management Science, 62(9), 2639–2650.

Graham, C. (2017). Happiness and economics: insights for policy from the new ‘science’ of well-being. Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy, 1(1), 69–72.

Grant, A. M. (2008). Employees without a cause: The motivational effects of prosocial impact in public service. International Public Management Journal, 11(1), 48–66.

Harrison, D. A., Newman, D. A., & Roth, P. L. (2006). How important are job attitudes? Meta-analytic comparisons of integrative behavioral outcomes and time sequences. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 305–325.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(2), 268.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., Asplund, J. W., Killham, E. A., & Agrawal, S. (2010). Causal impact of employee work perceptions on the bottom line of organizations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 378–389.

Heinz, M., Jeworrek, S., Mertins, V., Schumacher, H., & Sutter, M. (2017). Measuring indirect effects of unfair employer behavior on worker productivity – a field experiment. CEPR Discussion Paper, 12429.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2011). Well-being and trust in the workplace. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 747–767.

Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2015). How was the weekend? How the social context underlies weekend effects in happiness and other emotions for US workers. PloS one, 10(12), e0145123.

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Putnam, R. D. (2009). How’s the Job? Are trust and social capital neglected workplace investments? In V. O. Bartkus & J. H. Davis (Eds.), Social capital: Reaching out, reaching in. London: Edward Elgar.

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2016). New evidence on trust and wellbeing. NBER Working Paper, 22450.

Helliwell, J. F., Aknin, L. B. Shiplett, H., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2017). Social capital and prosocial behaviour as sources of well-being. NBER Working Paper, 23761.

Hu, J., & Hirsh, J. B. (2017). Accepting lower salaries for meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1649.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science, 306(5702), 1776–1780.

Kelly, E. L., Moen, P., Oakes, J. M., Fan, W., Okechukwu, C., Davis, K. D., et al. (2014). Changing work and work-family conflict: Evidence from the work, family, and health network. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 485–516.

King, R. B., Karuntzos, G., Casper, L. M., Moen, P. E., Davis, K. D., Berkman, L. F., Durham, M., & Kossek, E. E. (2012). Work-family balance issues and work-leave policies. In R. J. Gatchel & I. Z. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health and wellness. New York: Springer.

Knight, C., & Haslam, S. A. (2010). The relative merits of lean, enriched, and empowered offices: An experimental examination of the impact of workspace management strategies on well-being and productivity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 16(2), 158.

Krause, A. (2013). Don’t worry, be happy? Happiness and reemployment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 96, 1–20.

Krekel, C., G. Ward, & De Neve, J.-E. (2019). Employee wellbeing, productivity and firm performance. CEP Discussion Paper, 1605.

Lazear, E. P., Shaw, K. L., & Stanton, C. T. (2015). The value of bosses. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 823–861.

Leslie, L. M., Manchester, C. F., Park, T. Y., & Mehng, S. A. (2012). Flexible work practices: A source of career premiums or penalties? Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1407–1428.

Luechinger, S., Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2010). Why does unemployment hurt the employed? Evidence from the life satisfaction gap between the public and the private sector. Journal of Human Resources, 45(4), 998–1045.

Mas, A., & Pallais, A. (2017). Valuing alternative work arrangements. American Economic Review, 107(12), 3722–3759.

Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2008). Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica, 75(297), 39–59.

Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., & Hill, R. (2011). Does enhancing work-time control and flexibility reduce turnover? A naturally occurring experiment. Social Problems, 58(1), 69–98.

Moen, P., Kelly, E. L., Fan, W., Lee, S. R., Almeida, D., Kossek, E. E., & Buxton, O. M. (2016). Does a flexibility/support organizational initiative improve high-tech employees’ well-being? Evidence from the work, family, and health network. American Sociological Review, 81(1), 134–164.

OECD. (2014). Balancing paid work, unpaid work and leisure, Online: http://www.oecd.org/gender/data/balancingpaidworkunpaidworkandleisure.htm. Accessed 08 Oct 2017.

OECD. (2017a). Employment: Time spent in paid and unpaid work, by sex, Online: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54757. Accessed 19 Oct 2017.

OECD. (2017b). OECD guidelines on measuring the quality of the working environment, Online: http://www1.oecd.org/publications/oecd-guidelines-on-measuring-the-quality-of-the-working-environment-9789264278240-en.htm. Accessed 24 Nov 2017.

Ogbonnaya, C., & Daniels, K. (2017). Good work, wellbeing and changes in performance outcomes: Illustrating the effects of good people management practices with an analysis of the National Health Service. London: What Works Wellbeing.

Oswald, A. J., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2015). Happiness and productivity. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(4), 789–822.

PwC Research. (2013). Rising sick bill is costing UK business £29bn a year, Online: http://pwc.blogs.com/press_room/2013/07/rising-sick-bill-is-costing-uk-business-29bn-a-year-pwcresearch.html. Accessed on 17 Apr 2019.

Social Research and Demonstration Corporation. (2014a). UPSKILL: A credible test of workplace literacy and essential skills training – Summary report, Online: http://www.srdc.org/media/199770/upskill-final-results-es-en.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2017.

Social Research and Demonstration Corporation. (2014b). UPSKILL: A credible test of workplace literacy and essential skills training – Technical report, Online: http://www.srdc.org/media/199774/upskill-technical-report-en.pdf. Accessed 29 Nov 2017.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2009). The paradox of declining female happiness. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(2), 190–225.

Tay, L., & Harter, J. K. (2013). Economic and labor market forces matter for worker well-being. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 5(2), 193–208.

The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. (2007). Mental health at work: Developing the business case. Policy Paper, 8.

Tenney, E. R., Poole, J. M., & Diener, E. (2016). Does positivity enhance work performance?: Why, when, and what we don’t know. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 27–46.

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230.

Van Praag, B. M., Frijters, P., & Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A. (2003). The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 51(1), 29–49.

What Works Centre for Wellbeing. (2017a). Briefing: Job quality and wellbeing, Online: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/job-quality-and-wellbeing/. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

What Works Centre for Wellbeing. (2017b). Briefing: Learning at work and wellbeing, Online: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/learning-at-work/. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

What Works Centre for Wellbeing. (2017c). Briefing: Team working, Online: https://www.whatworkswellbeing.org/product/team-working/. Accessed 27 Nov 2017.

White, M., & Bryson, A. (2013). Positive employee relations: How much human resource management do you need? Human Relations, 66(3), 385–406.

Whitman, D. S., Van Rooy, D. L., & Viswesvaran, C. (2010). Satisfaction, citizenship behaviors, and performance in work units: A meta-analysis of collective construct relations. Personnel Psychology, 63(1), 41–81.

Willis Towers Watson. (2014). Balancing employer and employee priorities: Insights From the 2014 global workforce and global talent management and rewards studies, Online: https://www.towerswatson.com/en/Insights/IC-Types/Survey-Research-Results/2014/07/balancing-employer-and-employee-priorities. Accessed 01 Dec 2017.

Wooden, M., Warren, D., & Drago, R. (2009). Working time mismatch and subjective well-being. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(1), 147–179.

Woolley, K., & Fishbach, A. (2015). The experience matters more than you think: weighting intrinsic incentives more inside than outside of an activity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 968–982.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201.

Wunder, C., & Heineck, G. (2013). Working time preferences, hours mismatch and well-being of couples: Are there spillovers? Labour Economics, 24, 244–252.

Yeager, D. S., Henderson, M. D., D’Mello, S., Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Spitzer, B. J., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). Boring but important: A self-transcendent purpose for learning fosters academic self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 559–580.

Yuan, L. (2015). the happier one is, the more creative one becomes: An investigation on inspirational positive emotions from both subjective well-being and satisfaction at work. Psychology, 6, 201–209.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Krekel, C., Ward, G., De Neve, JE. (2019). What Makes for a Good Job? Evidence Using Subjective Wellbeing Data. In: Rojas, M. (eds) The Economics of Happiness. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15835-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-15834-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-15835-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)