Abstract

Any satisfactory method of making a social choice should be in some measure representative of the individual criteria which enter into it, should use the range of possible actions, and should observe consistency conditions among the choices made for different data sets. Arrow’s Theorem, or the Impossibility Theorem, states that there is no social choice mechanism which satisfies such reasonable conditions and which will be applicable to any arbitrary set of individual criteria. This article sets out the proof of the theorem.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Arrow’s th

- Bentham J.

- Compensation principle

- Condorcet

- Marquis de

- Constitutions

- Edgeworth F.

- Hicks J.

- Impossibility th

- Independence of irrelevant alternatives

- Intransitivity

- Kaldor N.

- Pareto principle

- Preference orderings

- Rawls J.

- Scitovsky T.

- Sidgwick H.

- Single-peaked preferences

- Social choice

- Social welfare function

- Voting

JEL Classifications

Economic or any other social policy has consequences for the many and diverse individuals who make up the society or economy. It has been taken for granted in virtually all economic policy discussions since the time of Adam Smith, if not before, that alternative policies should be judged on the basis of their consequences for individuals; political discussions are less uniform in this respect, the welfare of an abstract entity, the state or nation, playing a role occasionally even in economic policy.

It follows that there are as many criteria for choosing social actions as there are individuals in the society. Furthermore, these individual criteria are almost bound to be different in some measure so that there will be pairs of policies such that some individuals prefer one and some the other. In the economic context, policies invariably imply distributions of goods, and in most policy choices, some individuals will receive more goods under one policy and others under the other. Individuals may also have different evaluations because of different concepts of justice or other social goals.

The individual criteria may be based on individual preferences over bundles of goods or individual preferences of a more social nature, with preferences over goods supplied to others. From the viewpoint of the formal theory of social choice, the criteria may even be judgements by others as to the welfare of individuals. The only assumption is that there is associated with each individual a criterion by which social actions are evaluated for that individual. Whatever their origin, these criteria differ from individual to individual.

Every society has a range of actions, more or less wide, which are necessarily made collectively. Much of the debate on the foundations of social decision theory began with criteria for evaluating alternative tariff structures, including as the most famous illustration moving from a tariff to free trade. The redistribution of income through governmental taxes and subsidies provides another important case of an inherently collective decision which would be judged differently by different individuals.

If every individual prefers one policy to another, it is reasonable to postulate, as is always done by economists, that the first policy should be preferred. The problem arises of making social choices (between alternative collective policies) when some individual criteria prefer one policy and some another.

The fundamental question of social choice theory, then, is the following: given a range of possible social decisions, one of which has to be chosen, and given the criteria associated with the individuals in the society, find a method of making the choice. Not all methods of decision would be regarded as satisfactory. The method should be in some measure representative of the individual criteria which enter into it. For example, we would want the Pareto condition to be satisfied, that an alternative not be chosen if there is another preferred by all individuals. The method should use all the data, that is, both the range of possible actions and the individual criteria, and there are consistency conditions among the choices made for different data sets.

A pure case of social choice in action is voting, whether for the election to an office or a legislative decision. Here, the candidates or alternative legislative proposals are evaluated by each voter, and the evaluations lead to messages in the form of votes. The social decision, which candidate to elect or which bill to pass, is made by aggregating the votes according to the particular voting scheme used. The social decision then depends on both the range of alternatives (candidates or legislative proposals) available and the ranking each voter makes of the alternatives.

Voting procedures have one very important property which will play a key role in the conditions required of social choice mechanisms: only individual voters’ preferences about the alternatives under consideration affect the choice, not preferences about unavailable alternatives.

Arrow’s Theorem, or the Impossibility Theorem, states that there is no social choice mechanism which satisfies a number of reasonable conditions, stated or implied above, and which will be applicable to any arbitrary set of individual criteria.

Some terminology will be introduced in section ‘The Language of Choice’ of this entry. In section ‘The Relevant Literature’, there will be a brief review of the relevant literature as it was known to me prior to the discovery of the theorem. In section ‘Statement of the Impossibility Theorem’, I state the theorem with some variants and discuss the meaning of the conditions on the social choice mechanisms.

The Language of Choice

The formulation of choice and the criteria for it are those standard in economic theory since the ‘marginalist revolution’ of the 1870s as subsequently refined. There is a large set of conceivable alternatives; in any given decision situation, some given subset of these alternatives is actually available or feasible. This subset will be referred to as the opportunity set. Each individual can evaluate all alternatives. This is expressed by assuming that each individual has a preference ordering over the set of all alternatives. That is, for each pair of alternatives, the individual either prefers one to the other or else is indifferent between them (completeness), and these choices are consistent in the sense that if alternative x is preferred or indifferent to alternative y and y is preferred or indifferent to z, then x is preferred or indifferent to z (transitivity). This preference ordering is analogous to the preference ordering over commodity bundles in consumer demand theory. I have adopted the ordinalist viewpoint that only the ordering itself and not any particular numerical representation by a utility function is significant.

The profile of preference orderings is a description of the preference orderings of all individuals. For a given profile, the social choice mechanism will determine the choice of an alternative from any given opportunity set. In the case of an individual, it is assumed that the choice made from any given set of alternatives is that alternative which is highest on the individual’s preference ordering. Analogously, it is assumed that social choices can be similarly rationalized. The social choice mechanism will have to be such that there exists a social ordering of alternatives such that the choice made from any opportunity set is the highest element according to the social ordering.

Therefore, a social choice mechanism or constitution is a function which assigns to each profile a social ordering.

The Relevant Literature

I will here review the literature on the justification of economic policy as I knew it in 1948–50. There was some work in economics and more in the theory of elections of which I was unaware, which I will briefly note.

The best-known criterion for what is now known as social choice was Jeremy Bentham’s proposal for using the sum of individuals’ utilities. Curiously, despite its natural affinity with marginal economics, it received very little serious use, possibly because its distributional implications were unacceptably extreme. Edgeworth applied the criterion to taxation (1925: originally published in 1897): see also Sidgwick (1901, ch. 7).

The use of the sum-of-utilities criterion required interpersonally comparable cardinal utility. A reluctance to make interpersonal comparisons led to the proposal of the compensation principle by Kaldor (1939) and Hicks (1939). Consider a choice between a current alternative x and a proposed chance to another alternative y. In general, some individuals will gain by the change and some will lose. The compensation principle asserts that the change should be made if the gainers could give up some of their goods in y to the losers so as to make the losers better off than under x without completely wiping out the gains to the winners. Notice that the compensation is potential, not actual. Since the only information used is the preference relation of each individual among three different alternatives, x, y, and a potential alternative derived from y by transfers of goods, no interpersonal comparisons are needed.

However, it turns out that the compensation principle does not define a social ordering. Indeed, Scitovsky (1941) showed that it was possible that the compensation principle would call for changing from x to y and then from y to x.

A different approach which sought to avoid not only interpersonal comparisons but also cardinal utility was the social welfare function concept of Bergson (1938). For each individual, first choose a utility function which represents his or her preference ordering. Then define social welfare as a prescribed function W(U1, …, Un) of the utilities of the n agents. For a given profile of preference orderings, if one of the utility functions is replaced by a monotone transformation (which represents therefore the same preference ordering), the function W has to be transformed correspondingly, so that social preferences defined by W are unchanged. In this formulation, a given social welfare function is associated with a given profile. There are no necessary relations among social welfare functions associated with different profiles.

It was also known to me, though I do not know how, that majority voting, which could be considered as a social decision procedure, might lead to an intransitivity. Consider three voters A, B and C and three alternatives, a, b and c. Suppose that A has preference ordering abc, B has ordering bca, and C the ordering cab. Then a majority prefer a to b, a majority prefer b to c, and a majority prefer c to a. Therefore, if we interpret a majority for one alternative to another as defining social preference, the relation is not an ordering. This paradox had in fact been discovered by Condorcet (1785), and there had been a small and sporadic literature in the intervening period (for an excellent survey, see Black 1958, Part II; also, Arrow 1973), but all of this literature was unknown to me when developing the Impossibility Theorem.

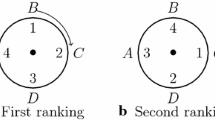

There was one further very important paper, which I did know, the remarkable paper of Black (1948) on voting under single-peaked preferences. Suppose the set of alternatives can be represented in one dimension, for example, a choice among levels of expenditure (this was the case studied by Bowen (1943) who anticipated part of Black’s results). Suppose individuals have different preference orders over the alternatives, but these preferences have a common pattern; namely, there is a most preferred alternative from which preference drops steadily in both directions. Put another way, of any three alternatives, the one in the intermediate position is never inferior to both of the others. Under this single-peakedness condition, majority voting defined a transitive relation and therefore an ordering. Hence, if the preferences of individuals are restricted to satisfy the single-peakedness condition, there does exist a constitution as defined earlier.

Statement of the Impossibility Theorem

I now state formally the conditions to be imposed on constitutions and then state the Impossibility Theorem, which simply asserts the non-existence of constitutions satisfying all of the conditions. The theorem as stated in the original paper (Arrow 1950) and in a subsequent book (Arrow 1951) is not correct as written, as shown by Blau (1957). To avoid confusion, I give a corrected statement and then explain the error.

Condition U: The constitution is defined for all logically possible profiles of preference orderings over the set of alternatives.

Condition M (Monotonicity): Suppose that x is socially preferred to y for a given profile. Now suppose a new profile in which x is raised in preference in some individual orderings and lowered in none. Then x is preferred to y in the social ordering associated with the new profile.

Condition I (Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives): Let S be a set of alternatives. Two profiles which have the same ordering of the alternatives in S for every individual determine the same social choice from S.

To state the next condition, it is necessary to define an imposed constitution as one in which there is some pair of alternatives for which the social choice is the same for all profiles.

Condition N (Non-imposition): The constitution is not imposed.

A constitution is said to be dictatorial if there is some individual, any one of whose strict preferences is the social preference according to that constitution.

Condition D (Non-dictatorship): The constitution is not dictatorial.

Theorem 1

There is no constitution satisfying Condition U, M, I, N and C.

A sketch of the argument can be given. From Condition I, the preference between any two alternatives depends only on the preferences of individuals between them and not on preferences about any other alternatives. Define a set of individuals to be decisive for alternative x against alternative y if the social preference is for x against y whenever all the individuals in the set prefer x to y. First, it can be shown that a set which is decisive for one alternative against one other is decisive for any alternative against any other. Hence, we can speak of a set of individuals as being decisive or not without reference to the alternatives being considered. If a set is not decisive, its complement (the voters not in the given set) can guarantee a weak preference, that is, preference or indifference. The set of all voters can easily be shown to be decisive, so there are decisive sets. The second stage in the proof is to take a decisive set with as few members of possible. If there were only one member, then by definition there would be a dictator, contrary to Condition D. Therefore, split the smallest decisive set so chosen into two subsets, say V1 and V2, and let V3 contain all other voters. We now use an argument similar to that which showed the intransitivity of majority voting. Take any three alternatives, x, y and z. Suppose the members of V1 all have the preference ordering, xyz, the members of V2 the ordering yzx, and the members of V3 the ordering zxy. Since V1 and V2 each have fewer members than the smallest decisive set, neither is decisive. Since all voters other than those in V2 prefer x to y, x must be preferred or indifferent socially to y. Since V1 and V2 together constitute a decisive set and y is preferred to z in both sets, y must be preferred socially to z. By transitivity, then, x is socially preferred to z. But x is preferred to z only by the members of V1, which would therefore be decisive for x against z and hence a decisive set. This, however, contradicts the construction that V1 is a proper subset of the smallest decisive set and therefore is not a decisive set. The theorem is therefore proved.

Notice that Condition U, that the constitution be defined for all profiles, is essential to the argument. We consider the consequences of particular profiles.

In Arrow (1951, p. 59), the theorem is stated with a weaker version of Condition U (and a corresponding restatement of Condition M).

Condition U′: The constitution is defined for a set of profiles such that, for some set of three alternatives, each individual can order the set in any way.

Since the contradiction requires only three alternatives, I supposed that the more general assumption would be sufficient. This is not so, as first pointed out by Blau (1957). The reason is that the non-dictatorship Condition D may hold for the set of all alternatives and not hold for a subset, such as the triple of alternatives just described. To illustrate, suppose there are four alternatives altogether. Let S be a set of three of them, and let w be the fourth. Suppose each individual may have any ordering such that w is either best or worst. There are two individuals in the society. The constitution provides that the social preference between any pair in S follows the preferences of individual 1, but w is best or worst according to individual 2’s preference ordering. This constitution would satisfy all the conditions of the Arrow 1951 version and therefore provides a counter-ex. What is true, of course, is that individual 1 is a dictator over the alternatives in S. If we still wish to retain the weaker Condition U′, the theorem remains valid if a stronger non-dictatorship condition is imposed (see Murakami 1961).

Condition D′: No individual shall be a dictator over any three alternatives.

The conditions are fairly straightforward and need little comment. If it is reasonable to limit the range of possible individual orderings because of prior knowledge about the range of possible beliefs, then Condition U or U′ could be replaced by a corresponding range condition. As has already been remarked, if preference orderings are restricted to the single-peaked type, then majority voting defines a constitution. There has been a considerable literature on range restrictions which imply that majority voting defines a constitution and some on more general voting methods. In a world of multi-dimensional issues, these restrictions are not particularly persuasive.

Conditions M and N embody different aspects of the value judgement that social decisions are made on behalf of the members of the society and should shift as values shift in a corresponding way. Condition D expresses a very minimal degree of democracy.

Condition I (independence of irrelevant alternatives) is central to the social choice approach whether in the Impossibility Theorem or in other, more positive, results. It is implicit in Rawls’s difference principle of justice (Rawls 1971), as well as in utilitarianism or methods based on voting.

The above conditions have not included the Pareto principle explicitly.

Condition P: If every individual prefers x to y, then x is socially preferred to y.

It is not hard to prove, however, that this condition is implied by some of the previous conditions, specifically Conditions M, I and N. Further, if the Pareto condition is imposed, then the Impossibility Theorem holds without assuming Monotonicity or Non-imposition. Of course, it is obvious that the Pareto principle implies Non-imposition, since any choice can be enforced by unanimous agreement.

Theorem 2

There is no constitution satisfying Conditions U, P, I, and D.

This entry has dealt with Arrow’s theorem itself and not with subsequent developments, which have been very abundant. The reader is referred to the entry on social choice in this work, and the surveys by Sen (1986) and Kelly (1978).

Bibliography

Arrow, K.J. 1950. A difficulty in the concept of social welfare. Journal of Political Economy 58: 328–346.

Arrow, K.J. 1951. Social choice and individual values. New York: Wiley. (2nd edn, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963, identical except for an additional chapter.)

Arrow, K.J. 1973. Formal theories of social welfare. In Dictionary of the history of ideas, ed. P.P. Wiener, vol. 4, 276–284. New York: Scribner’s.

Bergson (Burk), A. 1938. A reformulation of certain aspects of welfare economics. Quarterly Journal of Economics 52: 310–334.

Black, D. 1948. On the rationale of group decision-making. Journal of Political Economy 56: 23–34.

Black, D. 1958. Theory of committees and elections. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blau, J. 1957. The existence of social welfare functions. Econometrica 25: 302–313.

Bowen, H.R. 1943. The interpretation of voting in the allocation of economic resources. Quarterly Journal of Economics 58: 27–48.

Condorcet, M. de Caritat, Marquis de. 1785. Essai sur l’application de l’analyse à la probabilité des decisions rendues à la pluralité des voix. Paris: Imprimerie Royale.

Edgeworth, F.Y. 1897. The pure theory of taxation. In Papers relating to political economy, ed. F.Y. Edgeworth, vol. II, 63–125. London: Macmillan, 1925.

Hicks, J.R. 1939. The foundations of welfare economics. Economic Journal 49 (696–700): 711–712.

Kaldor, N. 1939. Welfare propositions of economics and interpersonal comparisons of utility. Economic Journal 49: 549–552.

Kelly, J.S. 1978. Arrow impossibility theorems. New York: Academic Press.

Murakami, Y. 1961. A note on the general possibility theorem of social welfare function. Econometrica 29: 244–246.

Rawls, J. 1971. A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Scitovsky, T. 1941. A reconsideration of the theory of tariffs. Review of Economic Studies 9: 92–95.

Sen, A.K. 1986. Social choice theory. In handbook of mathematical economics, ed. K.J. Arrow and M. Intriligator, vol. III, 1073–81. Amsterdam, North-Holland.

Sidgwick, H. 1901. Principles of political economy. 3rd ed. London: Macmillan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Arrow, K.J. (2018). Arrow’s Theorem. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_137

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_137

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences