Abstract

Background

The aims of this study were to create a method for estimation of dental age in Saudi children and adolescents based on the Willems model developed using the Belgian Caucasian (BC) reference data and to compare the ability of the two models to predict age in Saudi children.

Methods

Development of the seven lower left permanent mandibular teeth was staged in 1146 panoramic radiographs from healthy Saudi children (605 male, 541 female) without missing permanent teeth and without all permanent teeth fully developed (except third molars). The data were used to validate the Willems BC model and to construct a Saudi Arabian-specific (Willems SA) model. The mean error, mean absolute error, and root mean square error obtained from both validations were compared to quantify the variance in errors in the sample.

Results

The overall mean error for the Willems SA method was 0.023 years (standard deviation, ± 0.55), indicating no systematic underestimation or overestimation of age. For girls, the error using the Willems SA method was significantly lower but still negligible at 0.06 years. A small but statistically significant difference in total mean absolute error (11 days) was found between the Willems BC and Willems SA models when the data were compared independent of sex. The overall mean absolute error for girls was slightly lower for the Willems BC method than for the Willems SA method (1.33 years vs. 1.37 years).

Conclusions

The difference in ability to predict dental age between the Willems BC and Willems SA methods is very small, indicating that the data from the BC population can be used as a reference in the Saudi population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Estimation of dental age is a useful method for determining chronological age [1]. The scientific literature recommends calculation of dental age as the best method for age estimation in children, for whom there is a high correlation between chronological age and tooth growth [2]. Furthermore, dental age estimation has the least error in children [3] and has been found to be more useful than chronological age when planning orthodontic treatment [4].

Radiologically registered dental growth in children can be classified using the staging technique devised in 1973 by Demirjian et al. [5]. This method remains the one most commonly used for age estimation. Using a sample of French Canadian children, Demirjian et al. created a set of growth curves and tables, the validity of which has been confirmed in different populations [6, 7]. They also developed an age estimation method based on the developmental processes that occur in the permanent lower left teeth (excluding the third molar). The methodology developed by Demirjian et al. [5] for estimation of age has since been updated using a large sample of the Belgian Caucasian (BC) population by Willems et al. [8]. Some researchers have suggested that the Willems BC method performs better than other methods for estimation of dental age [2, 9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], one of the main reasons given being that it is based on a large sample of BC children with a more or less equal age and sex distribution (i.e., 2116 panoramic radiographs for children aged 3–18 years).

In Saudi Arabia, there is an increasing need for age estimation in children because of human trafficking, migration, asylum procedures, child pornography, adoption of children without a birth certificate, and legal decisions. When all seven teeth are available, the Willems approach shows the least difference when dental and chronological age are compared and could be used for age estimation [17]. Furthermore, the Willems method has been validated using multiple country-specific reference data [8]. However, the ability of the Willems method to predict age in Saudi children has not been well studied and it is unclear whether or not there is a need for a Saudi Arabian-specific reference method. Therefore, the present study aimed to validate the Willems BC method in a sample of Saudi children, create a Saudi Arabian-specific (Willems SA) method of age estimation, and to compare the ability of the two methods to predict age in these children.

Methods

Ethical approval to perform this study was granted by the institutional review board of Dar Al Uloom University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (approval number: RCE 0007-2017) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. A retrospective search of patient records at the Dar Al Uloom University Hospital and the School of Dentistry, Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University, Al-Kharj, Saudi Arabia for October 2016 to August 2017 yielded 1334 panoramic radiographs for 712 Saudi boys and 622 Saudi girls aged 4–18 years (Table 1). A total of 1146 subjects (605 boys and 541 girls) were < 16 years with no missing permanent teeth and did not have all permanent teeth of the left mandible fully developed. Only those were included in the analysis. Signed informed consent was obtained from each subject’s parents or legal guardians. Children were deemed to be of Saudi ethnicity if the names of both parents were of traditional Saudi origin. Each child’s birth date was registered from their birth certificate or another form of identification provided by their parents or guardians. At both centres, digital panoramic radiographs were acquired by an Orthophos XG5 machine (Sirona Dental Systems, Bensheim, Germany), which includes a digital charge-coupled device line sensor with exposure parameters of 14.1 s, 64 kV, and 8 mA. All images were stored in JPEG file format with a size of 2.5 MB and 2.440 × 1280 pixels.

The study inclusion criteria were excellent image quality and no evidence of a developmental dental abnormality in the medical history or on panoramic radiographs [18]. Radiographs in which two bilateral corresponding permanent mandibular teeth (other than the third molars) were absent were excluded [18]. To avoid observer bias, all panoramic radiographs were automatically sorted into numerical order before analysis and all other data were anonymised. The Photoshop® CS2 program (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose CA, USA) was used for stage allocation and allowed for magnification and enhancement of images when necessary.

All panoramic radiographs were evaluated using the methods described by Demirjian et al. in 1973 and by Willems et al. in 2001 [5, 8]. Only the seven lower left mandibular teeth (except for the third molar) were scored. First, each tooth was graded as ‘A’ to ‘H’ according to calcification stage (Fig. 1). Each score was then translated into a dental age based on sex as defined by Demirjian et al. and Willems et al. [5, 8]. Dental maturity scores were calculated for all seven left mandibular permanent teeth in both sexes using the weighted analysis of variance method used in the Willems BC model [8].

All panoramic radiographs were scored by three examiners. Two weeks later, the same examiners reviewed 100 randomly selected images. Differences between actual and predicted age were determined. The data were randomly categorised but stratified by sex and age into a test dataset and a training dataset. Specific regression coefficients were obtained for Saudi Arabian samples from a fit of the model on the full Saudi Arabian dataset using the Willems BC method [8]. The samples in the training dataset was fitted for a Saudi Arabian-specific model using the methodology of Willems et al. (2001). The test dataset was used to compare and validate the constructed Saudi Arabian-specific prediction model and the model devised by Willems et al. in 2001. The age prediction error was described as the difference between chronological age and estimated age (i.e., chronological age−estimated age) for comparison of the age prediction results. For calibration purposes, the error was expressed as the mean error (ME, representing both overestimations and underestimations) to quantify the direction of the error, mean absolute error (MAE) to quantify the magnitude of the error, and the root mean square error (RMSE) to quantify the variance in errors in the sample (assigning large errors more weight).

The interquartile range (lowest quartile, 25th percentile; highest quartile, 75th percentile) was calculated to concentrate on the data in the middle of the study. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the mean difference between chronological age and estimated age (ME, i.e., bias), the MAE, and the RMSE. Weighted kappa values were used to evaluate the interobserver and intraobserver reliability of the scores. The intraobserver reliability based on the first observer was 0.983 and the interobserver reliability was 0.919, indicating excellent agreement. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered as being statistically significant.

Results

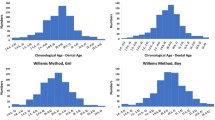

Table 2 shows the developmental stages based on Demirjian et al. (1973) categorised by age. The mean estimated age was not significantly different from the mean chronological age when both sexes were combined. Figures 2 and 3 show the calibration slope in the plot of chronological age (Willems BC method) against predicted age (Willems SA method) separately for girls and boys. There was no significant difference in the calibration slope between the two approaches. A negative value for the mean difference in chronological age against predicted age indicates overestimation and a positive value indicates underestimation of mean age.

On average, the estimated age was 0.02 years (standard deviation [SD] 1.78) higher than the chronological age, but was not statistically significant. Although there was no bias in boys, there was a small but negligible difference between predicted age and chronological age in girls, the predicted age being on average 0.06 years (SD 1.80) higher and − 0.01 years (SD 1.76) in boys (Table 3). The MAE was 0.02 years and was similar for boys and girls (1.34 years vs. 1.33 years), resulting in a mean RMSE for the total sample of 1.77 years (95 % confidence interval 1.71–1.84; Table 3).

Table 4 shows the regression coefficients for both sexes. The test dataset validated the efficiency of both the Willems BC method (5) and the newly developed Willem SA method. Table 5 demonstrates the mean difference (error), the absolute mean difference, the proportion of subjects with a predicted age within one year of chronological age, and a comparison of the mean RMSE for both strategies. Overall, the MAE and RMSE were slightly lower (albeit not significantly) using the Willems BC method. The relationship between age and error was comparable in magnitude using both approaches. The age of older subjects tended to be underestimated whereas that of younger subjects tended to be overestimated. The overall MAE for the Willems SA method was slightly higher than that for the Willems BC method (1.36 years vs. 1.33 years). There was also a slight variation in MAE for both approaches in both sexes.

Discussion

This research was performed to evaluate the population-specific weighted score that needs to be applied when the Willems BC method is used for estimation of dental age in Saudi children. The differences in ME, MAE and RMSE between the prediction from the Willems BC method and Willems SA method reflect the usefulness of the Belgian population as a reference.

Overestimation of dental age in relation to chronological age has been found in many studies. In a study performed in Malaysian children by Cherian et al. (2020), age was overestimated in children aged 6–15 years by an average of 0.04 ± 1.08 years in boys and by 0.03 ± 1.18 years in girls [19]. Furthermore, in a study of children in Bosnia and Herzegovina by Galic et al. (2011), age was overestimated by an average of 0.42 years in boys and by 0.24 years in girls [11]. Nevertheless, underestimation has been reported by other authors. Cameriere et al. (2008) applied the Willems method to children in Italy, Spanish and Croatia and observed that the age of girls was underestimated by age 0.07 and males overestimated by age 0.25 [20]. In addition, a study performed on central southern Chinese Han population aged 8–16 years by Yang et al. (2019), there was underestimation in females by 0.54 years and 0.44 years for males [21]. A possible explanation for the differences between overestimation or underestimation of dental age in relation to chronological age might be attributed to the different ethnic groups. The difference between boys and girls is most likely biological as often observed for the entire growth period between boys and girls. In this study, girls indicated advanced dental development and reached dental age maturation earlier than boys. Saudi Arabia’s legal system applies judicial punishment differently starting at the age of seven than it does at lower ages. A mother’s custody of her son and daughter ends when they reach the ages of 11 and 13, respectively. At the age of 15, permission to work is granted. People under the age of 18 may be committed to a rehabilitation center during their judgment.

In a study of Saudi boys and girls aged 8.5–17 years, Al Emran et al. (2008) noted that dental age was slightly older than chronological age by an average of 0.3 years in boys and 0.4 years in girls [22]; moreover, a study by Baghdadi (2013) found a mean difference of 0.77 ± 0.85 years in boys and 0.85 ± 0.79 years in girls [23]. A similar study by Qudeimat and Behbehani (2009) in Kuwaiti children aged 3–14 years found that dental age was overestimated by 0.71 ± 1.18 years in boys and by 0.67 ± 1.30 years in girls [24]. Our present findings in girls are consistent with the results of the above-mentioned three studies, but not for boys. However, a study in the Western Saudi population by Alshihri et al. in 2016 showed that Saudi girls were 0.059 ± 1.25 years and Saudi boys were 0.66 ± 1.14 years ahead of French Canadian children [25]. These findings indicate that genetic differences between Arab and European populations do not have a significant effect on dental growth or estimation of age and that the Willems model can be used to estimate age in Saudi children.

The Willems BC approach has not been validated or developed as a prediction model in the Saudi population. However, it was anticipated to perform well in Saudi children [26] based on the findings of studies in Japan [3], the United Arab Emirates [27], Brazil [28], and Malaysia [29], in which the Willems BC method was found to be suitable in those population samples. While a small overestimation of chronological age has been reported for the Willems BC method, both this method and the recently developed Malaysian-specific model have estimated age of similar magnitude and error variance. Our results confirm that the Willems BC method is accurate in Saudi children. Moreover, our findings are consistent with those of several previous studies [9, 14, 30]. Willems et al. found that the overall MAE was slightly higher with the Willems BC method than with a South African-specific method in black children (0.68 years vs. 0.62 years) [18]. However, Cadenas de Llano-Pérula et al. and Metsäniitty et al. found that the overall MAE was same the Willems BC method [31, 32]. Our result shows that the overall MAE to be slightly higher when using the Willems BC method than when using the Willems SA method (1.37 years vs. 1.33 years) and that the MAE was the same in boys and girls (1.37 years). We also found a small but statistically significant difference in the total MAE (11 days) and RMSE (11 days) for both sexes between the Willems BC and Willems SA methods (Table 5). However, our average age estimates for both sexes in a sample of the Saudi population are not significantly different from those estimated by the Willems BC method [8] (Table 3).

This research has some limitations that should be borne in mind when interpreting its results. The first is that the performance of the Willems BC method [8] was based on a broad reference database (n = 2116) whereas that of the Willems SA method was based on a smaller country-specific database (n = 1146). Furthermore, neither the Demirjian method nor the Willems method can be used in children with hypodontia in the mandible. A relative limitation of the study was that the subjects included here had undergone dental panoramic radiography for valid clinical reasons related to dental health and deviations from normal occlusal development, which explains the difference in sample numbers across the age groups.

In future research both permanent teeth and third molars might be integrated with the same model in order to produce an age estimation model that addresses most of the present shortcomings, especially within the ranges 15–17.99 years. The largest error in age estimation at present is this transition point between two age estimation approaches because the number of useful age-related parameters present is less.

Conclusions

In Saudi children, there is no need to use a Saudi Arabian-specific model instead of the Belgian reference database when estimating age. The difference in mean absolute error for age prediction was close enough to zero (0.03) to be considered clinically irrelevant. There was no systematic underestimation or overestimation of age. Although age estimation was significantly less accurate in girls, at 22 days it was still negligible in magnitude.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Belgian Caucasian

- SA:

-

Saudi Arabian

- ME:

-

Mean error

- MAE:

-

Mean absolute error

- RMSE:

-

Root mean square error

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Mohd Yusof MYP, Wan Mokhtar I, Rajasekharan S, Overholser R, Martens L. Performance of Willem’s dental age estimation method in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Forensic Sci Int 2017;280:245 e241-245 e210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.08.032.

Liversidge HM, Smith BH, Maber M. Bias and accuracy of age estimation using developing teeth in 946 children. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143(4):545–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.21349.

Ramanan N, Thevissen P, Fleuws S, Willems G. Dental age estimation in Japanese individuals combining permanent teeth and third molars. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2012;30(2):34–9.

Yusof MYPM, Mokhtar IW, Rajasekharan S, Overholser R, Martens L. Performance of Willem’s dental age estimation method in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Forensic Sci Int. 2017;280:245-e241.

Demirjian A, Goldstein H, Tanner JM. A new system of dental age assessment. Hum Biol. 1973;45(2):211–27.

Ifesanya JU, Adeyemi AT. Accuracy of age estimation using Demirjian method among Nigerian children. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2012;41(3):297–300.

Cavric J, Vodanovic M, Marusic A, Galic I. Time of mineralization of permanent teeth in children and adolescents in Gaborone, Botswana. Ann Anat. 2016;203:24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2015.08.001.

Willems G, Van Olmen A, Spiessens B, Carels C. Dental age estimation in Belgian children: Demirjian’s technique revisited. J Forensic Sci. 2001;46(4):893–5.

Maber M, Liversidge HM, Hector MP. Accuracy of age estimation of radiographic methods using developing teeth. Forensic Sci Int. 2006;159(Suppl 1):S68-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.02.019.

Mani SA, Naing L, John J, Samsudin AR. Comparison of two methods of dental age estimation in 7-15-year-old Malays. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(5):380–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-263X.2007.00890.x.

Galic I, Vodanovic M, Cameriere R, Nakas E, Galic E, Selimovic E, Brkic H. Accuracy of Cameriere, Haavikko, and Willems radiographic methods on age estimation on Bosnian-Herzegovian children age groups 6–13. Int J Legal Med. 2011;125(2):315–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-010-0515-8.

Grover S, Marya CM, Avinash J, Pruthi N. Estimation of dental age and its comparison with chronological age: accuracy of two radiographic methods. Med Sci Law. 2012;52(1):32–5. https://doi.org/10.1258/msl.2011.011021.

Medina AC, Blanco L. Accuracy of dental age estimation in Venezuelan children: comparison of Demirjian and Willems methods. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2014;27(1):34–41.

Ye X, Jiang F, Sheng X, Huang H, Shen X. Dental age assessment in 7-14-year-old Chinese children: comparison of Demirjian and Willems methods. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;244:36–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.07.027.

Onat Altan H, Altan A, Bilgic F, Akinci Sozer O, Damlar I. The applicability of Willems’ method for age estimation in southern Turkish children: a preliminary study. J Forensic Leg Med. 2016;38:24–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2015.11.015.

Nik-Hussein NN, Kee KM, Gan P. Validity of Demirjian and Willems methods for dental age estimation for Malaysian children aged 5–15 years old. Forensic Sci Int 2011;204(1–3):208 e201-206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2010.08.020.

Kelmendi J, Vodanovic M, Kocani F, Bimbashi V, Mehmeti B, Galic I. Dental age estimation using four Demirjian’s, Chaillet’s and Willems’ methods in Kosovar children. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2018;33:23–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2018.04.006.

Willems G, Lee S-S, Uys A, Bernitz H, de Llano-Pérula MC, Fieuws S, Thevissen P. Age estimation based on Willems method versus new country-specific method in South African black children. Int J Legal Med. 2018;132(2):599–607.

Cherian JM, Thomas AM, Kapoor S, Kumar R. Dental age estimation using Willems method: a cross-sectional study on children in a North Indian city. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol JOMFP. 2020;24(2):383.

Cameriere R, Ferrante L, Liversidge HM, Prieto JL, Brkic H. Accuracy of age estimation in children using radiograph of developing teeth. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;176(2–3):173–7.

Yang Z, Geng K, Liu Y, Sun S, Wen D, Xiao J, Zheng Y, Cai J, Zha L, Liu Y. Accuracy of the Demirjian and Willems methods of dental age estimation for children from central southern China. Int J Legal Med. 2019;133(2):593–601.

Al-Emran S. Dental age assessment of 8.5 to 17 year-old Saudi children using Demirjian’s method. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9(3):64–71.

Baghdadi ZD. Dental maturity in Saudi children using the Demirjian method: a comparative study and new prediction models. ISRN dentistry, 2013.

Qudeimat MA, Behbehani F. Dental age assessment for Kuwaiti children using Demirjian’s method. Ann Human Biol. 2009;36(6):695–704.

Alshihri AM, Kruger E, Tennant M. Dental age assessment of 4–16 year old Western Saudi children and adolescents using Demirjian’s method for forensic dentistry. Egypt J Forensic Sci. 2016;6(2):152–6.

Braga J, Heuze Y, Chabadel O, Sonan NK, Gueramy A. Non-adult dental age assessment: correspondence analysis and linear regression versus Bayesian predictions. Int J Legal Med. 2005;119(5):260–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-004-0494-8.

Altalie S, Thevissen P, Fieuws S, Willems G. Optimal dental age estimation practice in United Arab Emirates’ children. J Forensic Sci. 2014;59(2):383–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12351.

Franco A, Thevissen P, Fieuws S, Souza PH, Willems G. Applicability of Willems model for dental age estimations in Brazilian children. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;231(1–3):401 e401-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.05.030.

Yusof MY, Thevissen PW, Fieuws S, Willems G. Dental age estimation in Malay children based on all permanent teeth types. Int J Legal Med. 2014;128(2):329–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00414-013-0825-8.

Djukic K, Zelic K, Milenkovic P, Nedeljkovic N, Djuric M. Dental age assessment validity of radiographic methods on Serbian children population. Forensic Sci Int. 2013;231(1–3):398 e391-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.05.036.

Cadenas de Llano-Pérula M, Kihara E, Thevissen P, Nyamunga D, Fieuws S, Kanini M, Willems G. Validating dental age estimation in Kenyan black children and adolescents using the Willems method. Med Sci Law 2020:0025802420977379.

Metsäniitty M, Waltimo-Sirén J, Ranta H, Fieuws S, Thevissen P. Dental age estimation in Somali children using the Willems et al. model. Int J Legal Med. 2018;132(6):1779–86.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Steffen Fieuws for performing the statistical analyses and Prof. Dr. Guy Willem for the study protocol and comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Funding

This project was financially supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Dar Al Uloom University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA, MA, ZA and KA participated in the design of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript. AA, MA, ZA and KA read, corrected and approved the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval to perform this study was granted by the institutional review board of Dar Al Uloom University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (approval number: RCE 0007-2017) and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Signed informed consent was obtained from each subject’s parents or legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors state that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alqerban, A., Alrashed, M., Alaskar, Z. et al. Age estimation based on Willems method versus country specific model in Saudi Arabia children and adolescents. BMC Oral Health 21, 341 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01707-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01707-9